By Zita Ballinger Fletcher

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery is best known for defeating Germany’s famed commander, Erwin Rommel, at the Battle of El Alamein in 1942. Known as “Monty” to his troops, he reclaimed North Africa for the British in a series of lightning-fast battles using intelligence gained through codebreaking and experience honed by a career of hard struggles.

One of Montgomery’s arguably more important achievements was his crossing of the Rhine and seizure of northern Germany in the spring of 1945, which he accomplished with the same lightning-fast decisiveness as in Africa. Montgomery’s Rhine crossing and his subsequent decisions led to further military successes and advances in Allied governing policies.

He carefully planned Operation Plunder, a complex yet efficient Rhine crossing that created a springboard for one million Allied soldiers straight into Germany’s heartland across this heavily fortified river which, throughout Germany’s history, had been a fortress unto itself. Montgomery’s choice of Scots Highland “River Sweeper” soldiers contributed to the operation’s success.

One of Montgomery’s greatest achievements following the Rhine crossing was on a humanitarian level. He personally participated in the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Montgomery entered the camp with his troops and punished Nazi war criminals with a trial and execution process prior to the Nuremberg Trials. He ordered the gathering of evidence from the camp and denied clemency requests from the guilty. He also made the controversial decision to execute female war criminals. Montgomery’s actions ensured that Nazis responsible for torture and genocide in his zone of occupation did not escape punishment.

Finally, Montgomery’s steely acceptance of the German surrender at Lüneburg Heath helped end the war in Europe quickly and shaped Allied policy toward Germans in the British-occupied zone. Montgomery forced the Germans to negotiate on his terms and make concessions when they were not prepared to do so. He achieved this through deliberate psychological tricks, which fellow British officers remembered long afterward.

Bernard Montgomery is often typed as “headstrong” and “cocky” by modern critics, yet those characterizations fail to see beyond the surface of this complicated man, who made unparalleled achievements in military history through great personal sacrifice. Montgomery’s home country, Britain, suffered many losses during World War II that affected him.

His professional life was not easy. He described his career as a “constant struggle linked to many setbacks and disappointments.” This was no exaggeration. A closer look at Montgomery’s life prior to the 1945 Rhine crossing reveals a soldier hardened by storms of adversity. Undoubtedly, challenges contributed to his strong mindset and will to achieve victory.

Montgomery’s decision to become a soldier was a battle in itself. On his father’s side, he was of Northern Irish stock and identified with that part of his family. Growing up, he was a rowdy boy with great curiosity and a mischievous sense of humor. His mother, an austere and controlling Englishwoman, frequently beat him with a heavy cane for minor “offenses” such as climbing trees and picking mulberries.

She was, however, unable to curb his spirit. Montgomery channeled his energy into sports. He was a talented athlete who excelled at rugby and captained several teams. He set his heart on a military profession after seeing uniformed soldiers marching off to fight the Boer War in South Africa. Although his relatives strongly disapproved of his decision to join the military, Montgomery, fiercely independent, stood by his choice.

Montgomery chose to join the infantry. Joining the British Army’s Royal Warwickshire Regiment, he distanced himself from his family. He had the symbol of his regiment—an antelope—tattooed on his left forearm. “If I had my life over again, I would not choose differently,” he later wrote. “I would be a soldier.”

Montgomery was a highly analytical thinker with a calculating mind. When not in action, he immersed himself in studying military history and leadership and sought to hone his skills by fighting. While other British officers passed their careers quietly in the colonies, Montgomery found his way into the thick of every major conflict affecting the British Empire prior to World War II, including not only World War I but violent insurgencies in Ireland and Palestine.

He had many brushes with death. During World War I, then Lieutenant Montgomery nearly died after being shot through the lung by a German sniper. He fell, unable to move, and experienced harrowing moments as the sniper continued to target him. When another soldier rushed to his aid, the sniper shot the soldier dead and continued to target Montgomery.

He was shot again in the knee as he was pinned beneath the dead soldier’s body, which absorbed additional bullets intended for him. Montgomery’s gunshot wound to the lung should have been fatal, and indeed, his platoon abandoned him for dead. Medical staff expected him to die and dug a grave for him. It is a testament to Montgomery’s willpower that he escaped being buried alive. Against all odds, he made a full recovery.

TheLondon Gazettenoted Montgomery was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for “conspicuous gallant leading” at the time he was shot, and he was promoted to the rank of captain. Later in life, Montgomery described this battle experience but rarely mentioned receiving the DSO award. Returning to the field, he continued to demonstrate military talent as a young man. By 1918, he had become a chief of staff.

Montgomery saw further action against the Irish Republican Army during the Irish Civil War in the 1920s. The IRA led an insurgency against British authority, its tactics including assassinations and guerrilla attacks. Like many Northern Irish people, Montgomery identified himself as both British and Irish according to interviews and writings.

He saw further combat against violent insurgents in Palestine in 1938 and 1939. He successfully spearheaded efforts to counter an explosive civil rebellion. During this time, Montgomery had a tuberculosis scare, which made him deathly ill and put him in the hospital. Again, he made a complete recovery.

Montgomery’s hardships were not over; in fact, the chaos he experienced increased at the onset of World War II. A widower, Montgomery lost all his worldly possessions to Luftwaffe bombs when the Germans attacked the city of Portsmouth where Montgomery was garrisoned in an air raid on January 10, 1941.

This scenario was repeated in 1944, when his headquarters in France was targeted by German bombs, destroying additional personal property.

For all his hard knocks, Montgomery remained a tough and high-spirited man. He believed it was a commander’s duty to inspire optimism in subordinates, regardless of difficult personal emotions. Therefore, he did his utmost to radiate confidence and never permitted himself to show signs of uncertainty.

As a soldier, Montgomery was strict and self-disciplined, and he demanded the same discipline from others. He remained a zealous athlete throughout his life. In North Africa, he required “total fitness” from his troops in the hot climate. The athleticism he personally maintained during tropical service in India and Palestine allowed them no excuses. Some exercises he ordered for officers and men included running up and down stairs and a seven-mile march every week.

Although Montgomery was a firm and demanding leader, he did not view fear or threatening behavior as effective in motivating troops. His goal was to inspire his men through communication. He wrote that his method was to make soldiers “partners” with him in tasks and show them personal confidence.

Introducing himself as “Monty,” he used to climb onto the hood of his jeep to address his men, telling irreverent jokes and talking sports between discussing his battle plans.

“I used to talk to the soldiers, addressing them in large gatherings and telling them what we were going to do, my plans for doing it, and their part in the whole affair,” he described his approach. “Once the soldiers knew what was required of them and why and when, they never failed to do their stuff.”

At the time he prepared to cross the Rhine in 1945, Montgomery had experienced a dizzying rise in his career and in responsibility. He had transformed from an obscure British commander to an international public figure entrusted with the lives of literally millions of soldiers from the British Empire and Allied countries.

As a tactician, Montgomery possessed a strange combination of meticulousness and boldness. His victory at El Alamein showcased his approach to combat. His enemy, Erwin Rommel, seeking to hold German positions in North Africa in 1942, cleverly wedged his Afrika Korps between natural obstacles and a potent minefield. Montgomery responded to this, after calm and careful preparation, by distracting German attention in the wrong direction then literally pulling up the minefield and advancing through it during a blinding artillery barrage.

The complex assault was perfectly executed. The horrified Germans quickly lost ground. Besides the attack, Montgomery’s showmanship and the “shock value” of his sudden appearance were also effective. General Georg Stumme, then leading the Afrika Korps in Rommel’s absence, literally dropped dead of a heart attack.

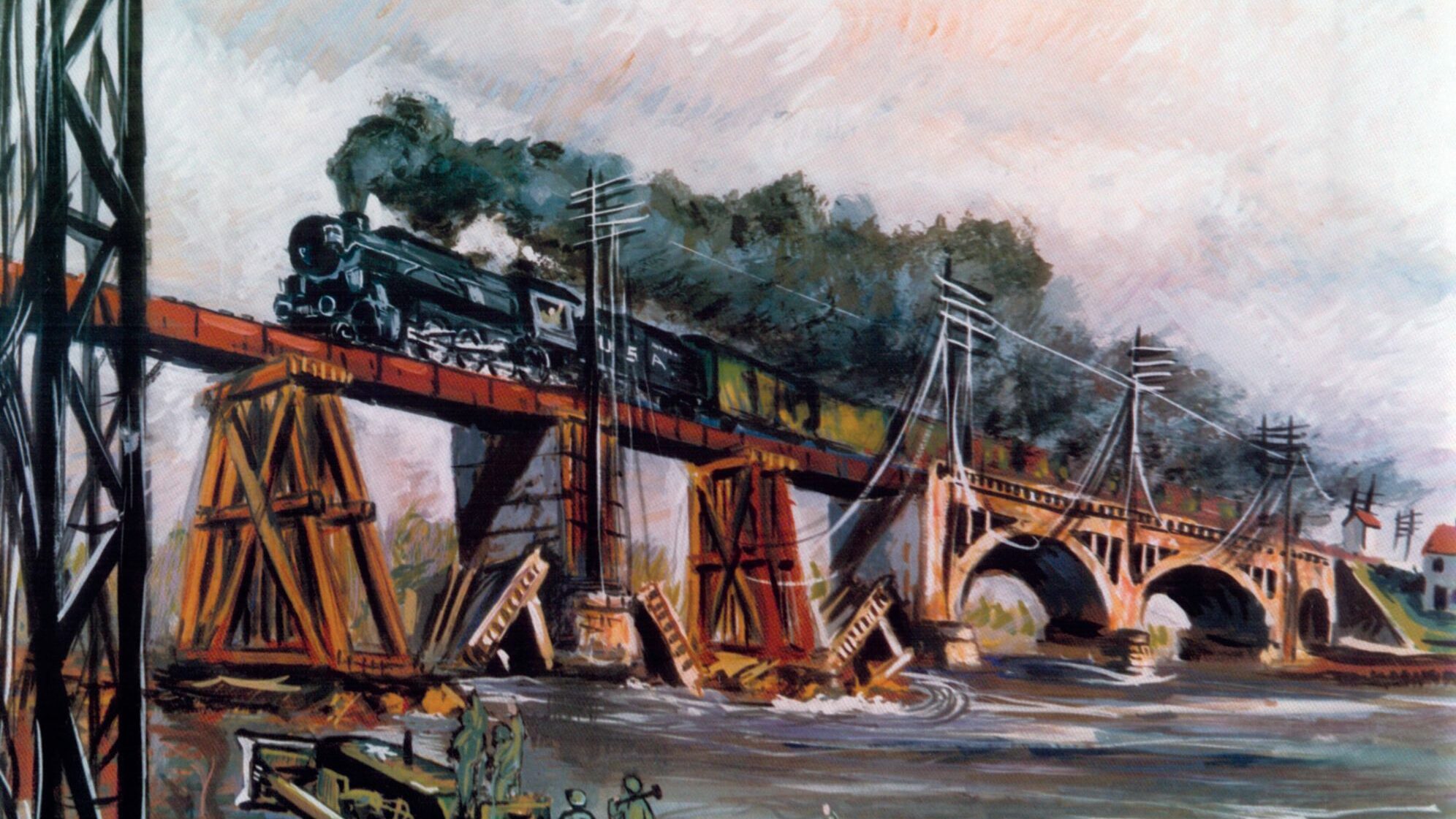

Bridging the Rhine would be a much more difficult task. For centuries, the Rhine had been a German stronghold, a natural defense barrier, a prized water transport route, and a cultural symbol of Germany. Montgomery was about to shatter the spirit of German victory that surrounded the river for hundreds of years with another intricate yet ruthlessly efficient plan called Operation Plunder. He planned to break across the Rhine in a direct frontal assault.

The main attack of Operation Plunder began at 7 pm on March 23, 1945. The crossing was led by Scots of the 51st Highland Division, who drifted across the water under a thick pall of smoke, while Germans defending the Rhine beaches attempted to sink the intruders with mortar fire. Aiming at the Allied invaders was no easy task. Prior to the attack, Montgomery had created a vast, opaque smoke screen stretching over 65 miles long.

The Germans were keenly aware of the Allied ambition to cross the Rhine and had attempted to bolster its defenses. In November 1944, Hitler ordered the fortification of the Rhine from Emmerich to Karlsruhe. Bridgehead defenses were concentrated along the major Rhine cities and bends in the river. River fortifications of this new Rhein-Stellung were to be booby-trapped with a 18-mile-deep obstacle field.

Between December 1944 and January 1945, German Army Group H attempted to bulwark Rhine defenses from the Nijmegen area to Wesel. A bitter winter of defeat and Allied strikes in the spring slowed progress on these defenses, ensuring that most of Hitler’s planned Rhein-Stellung never saw the light of day. The Germans had, on the other hand, already destroyed Rhine bridges and progressed on defensive outworks as Montgomery and his men set their sights on gaining a firm foothold on the river’s shores.

Operation Plunder was an ambitious and massive offensive, and is considered the largest amphibious assault river crossing in history. It was carried out in conjunction with Operation Varsity, a devastating air assault launched on Rhine defenses to obliterate enemy positions and demoralize potential resistance from the local Volksturm militias. Montgomery led both operations.

At the same time, he managed a third offensive called Operation Archway, sending SAS Special Forces troopers across the river behind enemy lines to scout and break German resistance. This complex, meticulous, and forceful approach was typical of Montgomery. Under his command, an estimated 16,000 soldiers from Britain, the United States, and Canada successfully carried off joint air and river-crossing operations with precision and a shattering element of surprise.

Montgomery showed discretion in choosing which British divisions to send into certain areas of battle. He believed that his men, gathered from diverse areas, were endowed with special fighting skills unique to their home regions.

“The miners from Durham and Newcastle, the men from the Midlands, the Cockneys, the farmers from the West Country, the Scot, the Welshman—all are different,” he wrote. “Some men are good at night; others prefer to fight in daylight. Some are best at the fluid and mobile battle; others are more temperamentally adapted to the solid killing match in close country. Therefore, all divisions are different.”

Montgomery chose troops from the 15th and 51st Highland Divisions to lead the amphibious assault. Montgomery held the Scots in high esteem and prized their toughness and rugged spirit. He praised their achievements in North Africa and said that an unforgettable experience in his life was witnessing his Scottish soldiers march in a victory parade in Tripoli in February 1943. “Every man an emperor,” he said of their battle pride.

The Scots were proven to be skilled at river fighting and were dubbed “River Sweepers” by comrades following previous successes during Operation Veritable (February 8-March 11, 1945) through the watery Reichswald, or Imperial Forest, near Kleve. Infantrymen of Scotland’s famous Black Watch battalion were first to cross Germany’s legendary Rhine under cover of smoke and darkness in rafts and amphibious armored vehicles called Buffaloes.

The Operation Plunder attack, launched across a 25-mile front, began with what the Associated Press described as an “earth-shaking” artillery barrage, accompanied by bombing and strafing. British commandos slipped over the river and crept within 1,500 yards of the city of Wesel as the RAF pounded the city into flaming rubble.

Entrenched German soldiers of the First Parachute and Fifteenth Armies made desperate attempts with artillery to stave off the British. Germans in the city of Rees fought back with grim determination and inflicted casualties on the Highlanders. Following aerial bombardments, British infantrymen stormed the ruined Rhine cities, shooting defenders and taking prisoners.

It was not long before German resistance over the hallowed Rhine River collapsed. Montgomery’s forces quickly secured the east bank of the river near Rees and Wesel and established four crossing points. It took a mere nine hours for Allied forces to create bridges across the river, and a million Allied soldiers swarmed across the river that had guarded the German homeland for centuries. Allied troops began a rapid advance across open country.

Operation Plunder, although complex, was carried off successfully and with comparatively low Allied casualties. Earlier in March 1945, Third Reich spokesmen had issued public statements insisting Germany would keep fighting. This resolve quickly disintegrated after the Rhine was completely breached at the end of the month.

Immediately after Operation Plunder, Montgomery gained new territory and new challenges. His advance was accompanied by roving SAS guerrillas who crossed the Rhine on March 25 to penetrate enemy lines. These intrepid Special Forces troopers brought Nazi atrocities to Montgomery’s attention and created a demand for him to exercise wartime authority in an unprecedented way.

One of Montgomery’s most significant wartime achievements after crossing the Rhine was not actually made in battle. Merely two miles from his mobile headquarters at Lüneburg Heath lurked a hidden horror: the infamous concentration camp Bergen-Belsen, discovered accidentally by British soldiers. A famous personality who perished there was teenage diarist Anne Frank, who died in the camp just weeks before Montgomery and his troops arrived.

Soon, Montgomery was drawn into the thick of the toxic atmosphere and forced to create order from the chaos. This led him to initiate a tough crackdown against Nazi war criminals, culminating in court proceedings that influenced the Allied approach to the Holocaust and war crimes.

“During the years of the Nazi regime in Germany, things happened which could not find a parallel in the most debased days of the Roman or Mongol empires, crimes were committed which most people could not imagine, unless they had seen a place like Belsen, which I entered on the day of its liberation by my troops in April 1945,” Montgomery wrote, adding, “The wholesale liquidation of civilians was unprecedented.”

At that time, concentration camps had only begun to be discovered. News of atrocities in these camps had just begun to leak out. The Red Army had discovered the remains of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in January 1945. Despite this, skepticism remained about Russian claims because the horrors were not verified by Western observers.

April 1945 brought a major turning point, however, as British and American forces began literally stumbling across concentration camps in their line of advance. Moving southwest into Germany in April, U.S. troops discovered forced labor camps, most notably the sprawling complex of Buchenwald. A delay in action resulted. American military leaders toured the camp in shock. Reporters flew to tour the scene. Meanwhile, the prisoners and the guilty remained in disorganization.

Belsen was the first major Nazi concentration camp to shake the international public consciousness. This was largely due to the handling of the situation by Montgomery, who took a direct approach to eradicating the camp, in contrast to his Allied counterparts.

Referred to as “hell on earth,” Belsen contained the worst examples of Nazi sadism. Prisoners there were primarily Jewish. Large numbers were women. Most were civilians. Among the worst female criminals in history tormented victims at this camp. These female Nazis were sadists who committed violent sexual torture against inmates, including mutilation and torturing pregnant women. They set attack dogs on wounded inmates, stripped prisoners naked and whipped them bloody.

Piles of corpses were everywhere. Survivors were covered in insects. When British soldiers discovered the camp, they witnessed starving inmates committing cannibalism. A suffocating stench stretched far down the road from the camp. German villagers living downwind pretended ignorance.

Montgomery quickly entered the scene with his troops. Many soldiers who entered Belsen with him that day were later unwilling or unable to describe what they witnessed. Like other British soldiers shocked by the experience, Montgomery did not describe atrocities in detail. Instead, after mentioning his firsthand discovery of Belsen in his postwar writings, he wrote the following emotional passage:

“All of these things were the responsibility of one evil man: Hitler. Millions starved and died while he and his followers feasted. He parted the wife from her husband, the maid from her lover, the child from its parents. If he had lived, he could never have given back what he had taken from those he had so cruelly wronged: years of life and health and happiness, wives and children, loved ones and friends. If he had ten thousand lives, they could not atone, even though each was dragged out to the bitter end in the misery which he meted out to others.”

Many British soldiers who liberated Belsen were young men in their 20s who remained traumatized for decades by what they saw. They were no doubt completely at a loss about what to do in the situation. Montgomery was faced with the immediate demand for a response.

The British could have postponed handling Belsen for a later date as they focused on military advances. They could have allowed prisoners to remain interned in the camp, assigned Germans onsite to burial duty, and let guilty Nazis slip through their fingers, as happened elsewhere.

Montgomery’s troops plunged into the fray. Under his orders, soldiers provided firsthand care to victims. The British took clothing from the homes of German villagers and used it to clothe naked prisoners. Beds were gathered. Nearby German Army barracks were transformed into makeshift hospitals. British soldiers washed and deloused victims, a gruesome task as most victims were covered in bugs and sores.

Soldiers also fed starved inmates with their own rations, which accidentally caused systemic shocks to camp survivors, who had been starving for a long time. Some died merely from eating ordinary food.

One British soldier serving under Montgomery defended his troops from postwar criticism about this, saying the soldiers behaved according to conscience. He described the prisoners as ravenously hungry and said the idea of withholding food from them was unimaginable then.

Large numbers of inmates were stricken with typhus. When medical personnel were summoned to the scene, they attempted to use intravenous methods to heal the starved and bony prisoners, but the victims of Nazi brutality became hysterical at the sight of needles. Rehabilitating these severely wounded people was a difficult undertaking.

Even while his men worked to revive the prisoners, Montgomery ordered evidence taken from the scene. He summoned Army photographers to document the atrocities and layout of the camp with pictures and notes.

He also ordered the imprisonment of all Nazi authorities at the camp. Witnesses pointed out who held roles of responsibility. Montgomery ordered some Nazi torturers to bury the corpses of people they had killed. British soldiers enforced this burial duty at gunpoint. Other concentration camp leaders were immediately taken into custody. To raise public awareness about the atrocities, Montgomery sent high-priority orders for the photographs of the camp and details about the crimes to be widely publicized. (The movie film of a British soldier bulldozing a pile of corpses is one of the most horrific scenes ever recorded.)

It was within Montgomery’s power to have the Nazi torturers detained in prison indefinitely or executed by firing squad. Instead, he called for a trial. Montgomery told his aides he wished to demonstrate British justice to Germans. He wanted to prove that, in contrast to Nazi barbarism, the British conducted themselves fairly and civilly.

Belsen thus became one of the most shocking Nazi death centers unveiled to the world. The trial was held in September 1945 at the town gymnasium in Lüneburg, which had been converted into a courtroom 10 days prior. A British military tribunal presided over the proceedings, which got underway as preparations were being made for the Nuremberg Trials. The Belsen Trial influenced public consciousness of Nazi cruelty and doubtlessly encouraged the strict legal atmosphere of the Nuremberg Trials.

Hundreds of reporters covered the Belsen Trial. The public first heard detailed evidence about crimes committed at Auschwitz, since many prisoners and guards had previously been at Auschwitz.

Unlike at Nuremberg, the Belsen Trial did not attempt to set new precedents by charging defendants with genocide or crimes against humanity. Instead, defendants were charged based on existing international laws of war at the time offenses were committed. Also, they were charged for offenses committed against specific, named victims. In this manner, British military authorities under Montgomery’s leadership ensured the perpetrators would be punished.

The trial also exposed previously unheard criminal defense arguments including brainwashing, propaganda, and the “following orders” excuses made by Nazi war criminals, all used as the basis for not-guilty pleas. In addition to the male defendants, female defendants were also charged with historically unparalleled crimes; three of them were sentenced to death.

The trial lasted only 54 days. All condemned had held camp leadership positions. Defense teams argued that the British broke the terms of the German surrender agreement by ordering executions. These arguments fell on deaf ears. According to the surrender terms, these members of the Nazi SS were eligible to be tried and punished.

Montgomery made arrangements for the criminals’ sentences to be carried out. He requested Britain’s top executioner, Albert Pierrepoint, to fly to Germany via special aircraft to hang the criminals at Hameln Prison in the fall of 1945.

Nine of the condemned appealed for clemency. One who campaigned hardest for Montgomery’s mercy was 22-year-old Irma Grese. The whip-toting, boot-wearing blonde systematically tortured female prisoners. A former Nazi medical experimenter with a vicious temperament, Grese was described by many inmates as deriving sexual satisfaction from acts of cruelty. She was unremorseful and contemptuous when captured.

After flaunting her neatness and control, Grese changed her act as her chances of survival waned. She wept, disheveled her hair, and regarded war correspondents with jitters and blinking red eyes to win pity. Her sister testified on her behalf as a “character witness,” blaming Grese’s behavior on a difficult childhood. Grese’s defense team told the press that, until the very last, she hoped Montgomery would commute her death sentence.

Montgomery was merciless in this matter. He swiftly denied Grese’s appeal and sentenced her to hang. His decision made history, as Grese was the youngest woman ever executed under British jurisdiction. He quickly denied all other appeals, personally signing the death warrants. All 11 Belsen ringleaders perished on the same day (December 13, 1945), and within half-hour intervals of each other. Montgomery wrote, “Justice cannot prevail without the sanction of force.”

The camp remnants were destroyed. Under Montgomery’s watch, the British Army evacuated all inmates to makeshift hospital facilities and burned down camp barracks to prevent the spread of disease. More than 1,000 former prisoners per day relocated to new shelters. On May 21, 1945, Montgomery authorized what was described as a “ceremonial burning” of the last of the camp barracks.

Flame-throwing tanks demolished the last trace of the Belsen horror camp in a purging fire. Photos show British soldiers and former inmates watching the place of torment disintegrate. It is unknown whether witnessing the destruction of this hellish prison gave victims relief. It is likely that Montgomery, with his emphasis on psychology and morale, intended the “ceremonial burning” to have psychological and symbolic value.

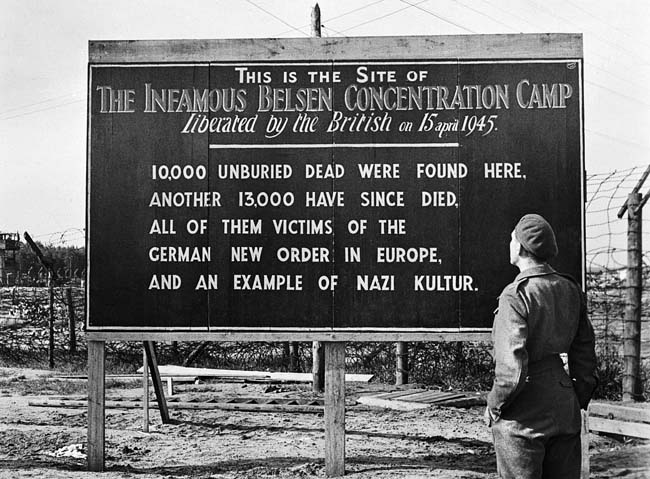

Later he ordered a huge billboard installed at the site. The large sign stated in English and in German a message in Montgomery’s typical blunt style: “This is the site of the infamous Belsen concentration camp, liberated by the British on 15 April 1945. Ten thousand unburied dead were found here. Another 13,000 have since died. All of them victims of the German New Order in Europe and an example of Nazi Kultur.” It was now impossible for locals to deny the existence of the camp or its conditions. Reality was visually inescapable.

Due to Montgomery’s swift actions, the guilty did not escape. None of the Nazi architects of horror at Belsen had a chance to sneak away to South America or disappear into the scenery. The trial was cold and civil, and justice was strongly delivered. “The true soldier is the enemy of the beast in man and of none other,” Montgomery later wrote. Evidently, the human bestiality he witnessed at the concentration camp remained with him for life.

After Montgomery’s Rhine crossing, the German government quickly deteriorated. Leadership of Germany quickly split into factions. Tensions that had existed for some time split open and divided the nation’s power. Ambitious Nazi leaders, including Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring, vied for status as Hitler’s successor before their supposedly beloved leader even drew his last breath. As the tattered but battle-ready Soviet Army advanced steadily from the east, a raving Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945, followed in rapid succession by several delusional followers. His successors continued to mislead the German people, announcing via radio that Hitler died fighting “at the head of his troops.” The truth of Hitler’s demise was not discovered until later.

Meanwhile, sizable German forces remained armed and ready to defend their besieged Fatherland. Although surviving Nazi leaders diverged in personal ambitions and plans, their determination was united in one thing: they did not want Germany to be completely overrun, and above all, not by the Russians.

As Nazi heirs apparent, Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring darted cross-country in different directions to save their lives and possessions, while the respected Admiral Karl Dönitz took the reins as head of state and approached the Allies in an attempt to wield control over Germany’s fate.

Dönitz chose to contact Montgomery, notorious in Germany as the formidable vanquisher of German war hero Erwin Rommel. The raffish charm that made “Monty” loved by and inspiring to his troops was lost in translation on the Germans, who had never been able to grasp Montgomery’s cutting sense of humor. The Germans perceived him as a fierce and pitiless man. That assessment was not entirely incorrect, and, when it came to negotiating surrender, Monty would live up to it.

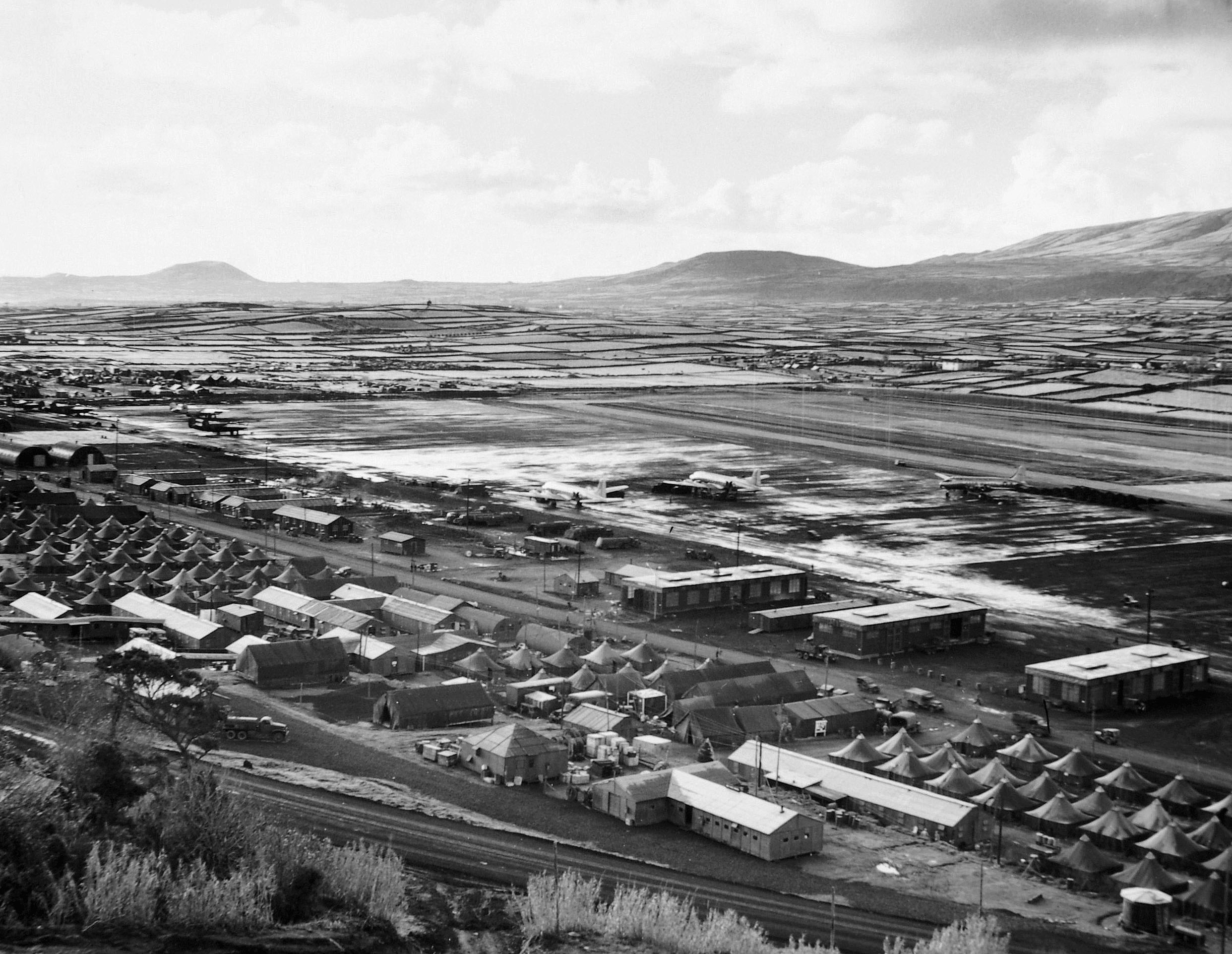

Montgomery was encamped on Lüneburg Heath, a dense woodland in northern Germany. On the front lines, Monty lived a gypsy lifestyle. He kept close to troops in the thick of forward battle areas. To accomplish this, he traveled in a fleet of caravans (trailers) and jeeps.

His tactical headquarters consisted of camouflaged vehicles suited for different purposes. One was a map room, one was his office, and one was his bedroom. There was also a mobile mess and a radio communications station that established contact with Allied forces and intercepted enemy messages. The fleet was jockeyed by a posse of men accustomed to Montgomery’s semi-nomadic habits. He was known to “nest” his headquarters in obscure areas, keeping everything shrouded with drapes of camouflage. He usually required an open area for a landing strip in case he needed to travel by air.

On May 2, 1945, Montgomery received a message that the German Army facing his troops would surrender the next day. Upon hearing this news, he informed fellow British commanders that he expected something greater would actually happen. His prediction was right. At 8 amthe next day, he received news that a delegation of four German officers was coming to seek a compromise. They wished to surrender, if agreeable terms could be reached.

Montgomery was left without much time to prepare for the negotiations. As usual, he reacted with decisiveness and a heavy dose of psychology. Summoning German interpreters, he ordered that a Union Jack be hoisted on a flagpole outside where he would receive the delegation.

According to witnesses, including interpreter Derek Knee, Montgomery ordered that the Germans be forced to stand under the British flag and wait for his arrival. Montgomery deliberately kept them waiting for half an hour before materializing.

When Montgomery arrived, he was dismissive and pretended not to know who the Germans were or what they wanted. He was belittling, demonstrating that their ranks and insignias were unimportant to him.

All of this might have seemed merely like arrogant behavior had not Montgomery’s aides testified to the deliberateness with which he planned it. His jabs were designed to knock the Germans off balance. In his writings, Montgomery expressed his battle philosophy: “The enemy must be forced to dance to your tune all the time.” The negotiations at Lüneburg Heath were certainly an awkward dance for the Germans.

The Germans attempted to bargain with Montgomery to advance their own military interests. They wanted to surrender troops on the Eastern Front to Montgomery to spare them from Russian captivity. They also wanted to keep forces in northern Germany in play, as Admiral Dönitz, Hitler’s successor, was setting up a new government in Flensburg. They believed they held leverage against Montgomery and tried to exercise it.

Montgomery replied he had no interest in their terms. “The only matter that I am concerned with is that all the German forces facing me surrender unconditionally,” he interrupted. “If you don’t want to do that, you can go home.”

The Germans, displeased, tried to appeal to Montgomery’s conscience to accept their terms to save civilian lives. The remarks angered Montgomery. According to eyewitness Ronald Playforth, Monty gave the German delegation a “tongue lashing” via interpreter about atrocities.

“Do you remember a little town in England called Coventry? It no longer exists,” said Montgomery, bringing up the bombing of England. Coventry was so badly devastated that it became a byword for destruction. Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels had even used it to invent a new German word—coventriert, or Coventrated—to describe bomb-flattened Allied cities.

Montgomery also cited his recent visit to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, adding the withering comment, “You are not the slightest bit interested in civilian lives.”

He threatened to give immediate orders for up to 10,000 bombers to begin heavy day and night raids on German territory that would kill civilians if unconditional surrender were not given. The Germans balked at the suggestion, claiming they had no authority to surrender unconditionally on the spot. “We’re not making any progress,” said Montgomery, and suggested the delegation consider the matter over lunch.

By inviting the Germans to lunch, Montgomery began another elaborate ruse he had prepared. Prior to the delegation’s arrival, British officers scrambled around on Montgomery’s orders to scrape rations into an illusory feast. Tables were decked with Army blankets and set with flowers. A buffet-style offering of coffee, brandy, and wine was spread out. Montgomery wanted to give the impression of idle luxury.

Witnesses said the war-weary Germans were shocked by the cornucopia of food available to the British upon entering the mess tent. They complimented the “wonderful meal.” .

Using an interpreter, Montgomery dismissed the comforts as commonplace. It is unknown whether Montgomery wished to emphasize that the British were supplied enough to hold up a long siege, or whether he wished to remind the Germans of their own food shortages. Perhaps he intended both. In any case, his wiles were effective in demoralizing the Germans.

Montgomery also set up a battle map, which he showed the Germans after lunch. He proceeded very calmly to illustrate Germany’s desperate position by describing strong Allied formations—including and especially the Russians—and pointing out key spots on the map. This final blow shattered the Germans’ resolve. They became visibly despondent. One German officer, in a rare show of despair, collapsed into tears.

At the conclusion of his presentation, Montgomery made his demand again with a concise speech. “You must understand three things. Firstly, you must surrender to me unconditionally all the German forces in Holland, Friesen, and the Frisian Islands and Helgoland and all other islands in Schleswig-Holstein and in Denmark,” he said.

“Secondly, when you have done that, I am prepared to discuss with you the implications of your surrender: how we will dispose of those surrendered troops, how we will occupy the surrendered territory, how we will deal with the civilians, and so forth.” The climax came next. “And my third point: If you do not agree to Point 1, the surrender, then I will go on with the war and I will be delighted to do so,” he declared boldly. “All of your soldiers and civilians may be killed,” he added.

The Germans had approached Montgomery intending to bargain. By the time Montgomery finished his subterfuges, they had lost faith in their own power. They agreed to present his surrender terms to Dönitz without requesting further negotiations.

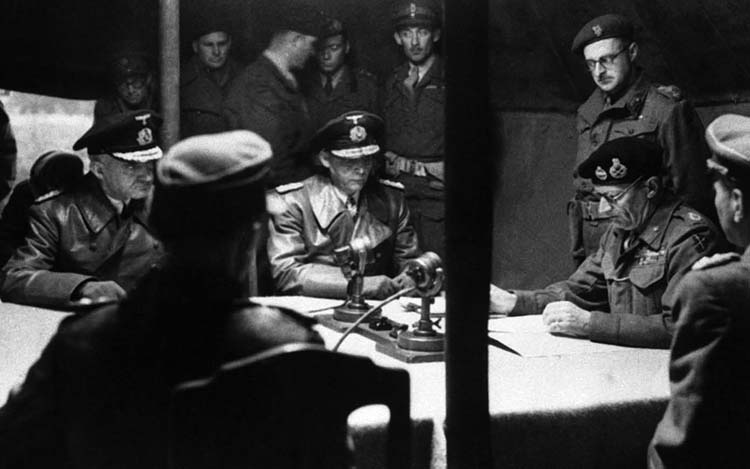

The delegation returned the next day, cameras were in place and reporters were present. Montgomery also arranged a flyover. The Germans on the hill were buzzed by a British bomber swooping low over their heads. Montgomery’s aides later claimed he did this to spook the Germans from having any defiant thoughts. He punctiliously edited the surrender document in preparation. In a historic moment captured on film, the Germans signed this document in Montgomery’s tent on Timeloberg Hill.

The surrender paved the way for VE Day in Europe as the Germans, collapsing like dominoes, surrendered to the Allied powers. Not long after the formal surrender, British troops captured Dönitz and his Flensburg government, subjugating Germany and ending the Third Reich.

The world celebrated, but Montgomery’s war was not over. He found himself in command of a zone of Germany as military governor, a task he, as a career soldier, personally loathed. The zone was beset with looting transients, refugees, and Nazi conspiracies. Also, the SS had been very active in the region, and their supporters did not disappear overnight. Infrastructure was nonexistent. Everything had been destroyed. Homes, businesses, and industries were in complete ruins. Nothing functioned. People were hungry, restless, and idle.

British soldiers attempted to establish cordial relations with the locals. Supreme Allied Command orders to penalize the German civilians for Nazism, though, complicated this. Montgomery felt conflicted about having to follow these directives. “I had never liked the orders which we had had to issue, but it was the Allied policy,” he wrote.

He was required to forbid Allied soldiers to even wave or smile at German civilians or to interact with children. The German civilians reacted badly to this hostility and became restive. To prevent an outbreak of conflict, Montgomery issued the following explanation to the civilian population:

“Many of you seemed to think that when our soldiers arrived, you could be friends with them at once, as if nothing much had happened, but too much has happened for that,” he stated, describing hardships soldiers under his command had endured during the war. “For those things, you will say you are not responsible—it was your rulers,” his order continued. “But they were found by the German nation. Every nation is responsible for its rulers, and while they were successful, you cheered and laughed. That is why our soldiers do not smile at you…. It will not always be so. For we are Christian, forgiving people…. Our object is to destroy the evil of the Nazi system. It is too soon to be sure that this has been done.”

Montgomery wrote that it eventually became impossible to prevent British soldiers from interacting with local civilians.

His attitude in this matter indicates that, surprisingly, Montgomery did not cultivate a hatred of Germans. Many men who liberated the Belsen camp with him wrote that they blamed the entire German race for what happened there and would never forgive the Germans as a people. Montgomery’s writings and expressions indicate that he had a different mindset.

He had studied and admired the writings of German thinkers during his life. His favorite music, according to a postwar interview he gave the BBC, included German operetta. Instead of denouncing Germans as racially monstrous at war’s end—which many people were then doing—Montgomery appears to have consigned guilt to individuals and focused on rebuilding his zone of occupation.

Montgomery wrote that he believed no progress could be made for peace as long as an atmosphere of hostility remained toward Germans, citing the aftermath of the World War I as an example. His priority as military governor was to delegate work to unemployed Germans. He conjectured that a healthy Germany largely depended on economic revival. His theory about Germany’s revival process ended up proving true as Germany, reconstructing itself with the aid of the Marshall Plan, transformed into an economic powerhouse in the postwar era.

The period Montgomery spent in Germany as a military governor was hazardous. The local population was not, in many cases, peaceful. He described many Germans in the region as “all-out Nazis.” Indeed, a conspiracy against British military occupiers was unearthed. Despite this, Montgomery did not adopt draconian measures. He maintained a firm grip on the occupied population, cultivating reconstruction without being too severe.

Montgomery made many personal sacrifices equal to those of his men. He spent literally years on the front lines without reprieve. The war left him with injuries, property loss, and hard memories that impacted the rest of his life.

Montgomery was injured in an August 1945 plane crash. He was traveling in a Miles Messenger aircraft when the engine stopped running in midair approaching a landing strip, and the plane dropped from the sky. Two other men in the small aircraft were unscathed, but Montgomery was badly injured with many bruises and two broken lumbar vertebrae.

Never one to show worry, Montgomery dismissed the painful injuries and took another flight the same day. However, he was weakened by five years on battlefronts and contracted influenza and pleurisy. Devoted to his work, Montgomery took only a single month of leave in 1946 to recover before continuing his duties. The crash caused back problems that took many years to recuperate from.

Montgomery was homeless by the war’s end. Most of his property was lost during the conflict—in addition to his destroyed belongings, even his pet terrier that traveled with him on the front lines was killed in 1944. His only living quarters were the mobile military caravans he had traveled in for the last several years. Returning to England, he lived in his vehicles parked outside for a period and used his savings to buy and refurbish an abandoned old mill in the countryside. The governments of Australia and Tasmania numbered among donors who supplied him with construction materials.

Montgomery’s grim wartime experiences left deep impressions on him. “In my adult life, during two world wars, there has been the most incredible cruelty inflicted on humanity by nations calling themselves civilized,” he wrote. As postwar tensions developed, Montgomery became disillusioned with the outcome of World War II. He wrote that he feared the peace his troops fought and died to achieve was a dimming prospect and that another war would render his men’s sacrifices made in vain.

At 71, Montgomery retired after more than 50 years of active-duty military service, an unprecedented accomplishment in British military history. In reality, the energetic general was far from retired. He devoted the rest of his life to actively promoting peace.

“The aim of the general must be not only to win wars but also to play his part in preventing them,” he wrote. “Nobody knows better than a soldier the overwhelming value of that prize, because nobody knows better than a soldier the monster called War.”

The fiery career fighter, however, was no pacifist. “Much good as well as evil is released in war,” he wrote. “When men are inspired to offer themselves to a high and noble cause, the hardships of war draw out of them their best qualities: comradeship, endurance, courage, self-sacrifice, willingness to die.”

He remained proud that he and his soldiers accomplished something good by defeating the Nazi system. “The peace we now enjoy is the peace of victory over the beast in men,” he wrote, “and this victory will not survive if the virtues which gained and sustain it are lost.”