By Michael D. Hull

General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, was a man both driven and under great pressure in the spring and early summer of 1942.

He wanted his bombers and fighters in the air as soon as possible, operating from airfields in Great Britain and joining the hard-pressed Royal Air Force in its offensive against Nazi Germany. He had promised British Prime Minister Winston Churchill action by July 4.

The jovial Arnold had to justify USAAF appropriations to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Congress, and the public. In addition, he had to maintain aircraft production and strategic priorities in the face of challenges from the British and the U.S. Navy. All of this required a perception of the USAAF as a successful and aggressive offensive weapon. FDR demanded results justifying the massive aircraft production and shipping program.

But by that summer, several months before it had become a force to be reckoned with, Arnold’s growing air arm also needed to have its image bolstered. Navy carrier planes had won the climactic Battle of Midway, June 4-6, 1942, while officials and the public were still disturbed about the USAAF’s performance in December 1941 at Pearl Harbor and in the Philippines, where large numbers of aircraft had been destroyed on the ground by Japanese raiders.

Arnold’s demands put pressure, in turn, on his main combat commander, Maj. Gen. Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz, who had recently arrived in England to head the newly formed U.S. Eighth Air Force, and Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, commander of the Eighth Bomber Command. While waiting for Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber groups to cross the Atlantic, the tireless, methodical Spaatz also had to satisfy the needs of Maj. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the new U.S. chief of European operations. The latter was busy with Operation Bolero, the buildup of war matériel in England for the coming invasion of Nazi-occupied Western Europe, and the planned invasion of North Africa later that year, which had been decided upon at the Arcadia Conference in Washington in December 1941-January 1942.

While Spaatz and Eaker lacked the planes for a major operation, the USAAF did send bombers against a European target for the first time on June 12, 1942. Led by Colonel Harry A. “Hurry Up” Halverson, a pioneering Army Air Corps flier, 13 Consolidated B-24D Liberator heavy bombers took off that day from the RAF airfield at Fayid, near the Suez Canal in Egypt, and attacked the German oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania. It was the first of a series of missions against the strategic target. Halverson’s B-24s bombed through heavy cloud, and only minimal damage was caused. Seven of the planes landed as planned in Iraq, two were interned in Turkey, and another crash landed. The raid passed almost unnoticed because headlines were full of the Navy’s triumph at Midway.

Planning the First Raid In Northwestern Europe

On June 28, General Spaatz received orders from the impatient Arnold to schedule a raid in northwestern Europe—the first for the USAAF—on Independence Day, six days hence. President Roosevelt had approved the mission, and he and Arnold believed that July 4 would be an appropriate day for the USAAF to open its aerial offensive against Germany. But Spaatz and Eaker considered the venture premature. Eaker’s B-17s had not arrived, and the 31st Fighter Group was learning to handle RAF Supermarine Spitfires.

Spaatz regarded the planned mission as a “stunt” triggered by the American press, which believed that the Allies needed a morale boost. But he went ahead, nevertheless, and chose a squadron of Eighth Air Support Command light bombers for the groundbreaking mission. The assignment fell to the 15th Bombardment Squadron (Light), which had arrived in England a few weeks before as part of a token U.S. force.

Constituted on December 22, 1939, and initially activated as part of the 27th Bombardment Group at Barksdale Field in Louisiana in February 1940, the 15th Squadron had been reassigned to the Fifth Air Support Command in late 1941 and based at the Fort Dix, New Jersey, Army airfield. After the Pearl Harbor attack, the unit flew antisubmarine patrols along the New York and New Jersey coasts.

The squadron was reassigned to Lawson Field in Georgia and manned by the personnel of the inactivated 27th Group, who had fought in the ill-fated Philippines campaign of 1941-1942. The unit was briefly redesignated the 1st Pursuit (Night Fighter) Squadron in April 1942 before being assigned to the Eighth Air Force in England. It was redesignated the 15th Bombardment Squadron (Light) on May 7, 1942, and arrived at the RAF’s big Grafton Underwood base in Northamptonshire on May 12. After being assigned to Eaker’s Eighth Bomber Command two days later, the unit moved to the RAF airfield at Molesworth, Cambridgeshire, on June 9.

The squadron was equipped with twin-engine Douglas A-20 light bombers from No. 226 RAF Squadron. Called Havocs by the Americans and Bostons by the British, A-20s had been used briefly by the French Air Force in Algeria and saw extensive service with the RAF in the Western Desert. In action later with the RAF and the USAAF in the European and Pacific Theaters until the end of the war, they flew in New Guinea, Guadalcanal, Sicily, Italy, Burma, and Normandy. A-20s also served with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps and the Australian, Canadian, South African, New Zealand, Free French, and Soviet Air Forces.

Manned by a crew of three, the versatile A-20 “attack bomber” had a maximum speed of 317 miles per hour, a bomb payload of up to 4,000 pounds, and mounted six .50-caliber forward-firing machine guns, two in a power operated dorsal turret and one in a ventral tunnel. Its ceiling was 25,000 feet and its range 1,025 miles.

The 15th Bombardment Squadron was commanded by 26-year-old Captain Charles C. Kegelman, a clean-cut, genial native of Oklahoma destined to become America’s first hero in the Allied aerial offensive in Europe.

Born on Friday, October 22, 1915, in the small agricultural town of El Reno on the North Canadian River in Oklahoma’s central Canadian County, Kegelman was the son of Missouri-born Charles Kegelman and his Nebraska-born wife, Alva. Young Charles had three sisters—Renee, Inez, and Anna. Nicknamed “Sonny,” the boy attended local schools, studied at the Oklahoma Military Academy until 1934, and then went to the University of Oklahoma to prepare for a medical career. But after graduation, aviation and a possible future in the Army Air Corps beckoned the young man.

Charles underwent flight training at Barksdale Airfield in Bossier City, Louisiana, and Savannah, Georgia, and attended a transition bomber pilots’ school in Nevada before being promoted to captain and ordered to England in the spring of 1942.

Kegelman and six of his inexperienced crews underwent several weeks of training in the Bostons and then moved to Swanton Morley in Norfolk, where they were attached to the RAF’s No. 226 Squadron commanded by Squadron Leader J.S. Kennedy. For the Independence Day raid the six American-manned bombers would accompany six RAF Bostons and be under overall British leadership. It was to be a low-level daylight raid against four German airfields near the North Sea coast of Holland. The operation was expected to be a “milk run.”

The Independence Day Raid

At 7:11 am on Saturday, July 4, the dozen light bombers started taking off from the small, grassy airfield at Swanton Morley. After assembling into four flights of three planes, with a seasoned RAF crew in each flight, the Bostons headed across the North Sea toward Holland. They flew low to avoid detection by enemy radar.

Everything went smoothly until they passed over two German “squealer” boats, which radioed a warning to defense outposts in Holland that hostile aircraft were approaching. When the Bostons droned across the Dutch coast, the Germans were ready. Antiaircraft batteries threw up salvos so intense that it shocked the veteran RAF crews.

The four flights split up to attack assigned targets. All pilots had been instructed to make their approaches and bomb runs flat and low. Intense fire greeted the three Bostons heading for the airfield at De Kooy. The leading RAF plane escaped, but an American-manned A-20 piloted by Lieutenant F.A. Loehrl had its nose blown off by a direct hit and crashed in flames.

The third Boston, piloted by Captain Kegelman, was shot up badly as it swept in low over the De Kooy airfield. Its starboard engine took a direct hit, the fuselage was ripped open, and the right wing was damaged. The right wingtip and rear of the fuselage scraped the ground, but Kegelman skillfully wrestled with the controls and managed to keep the plane airborne.

Kegelman jettisoned his bombs, and the crippled Boston swung away from the airfield—into the path of fire from a flak tower. But the American’s trigger finger was faster than the German’s as he silenced the tower with his nose guns. Then he steered the plane to the dubious safety of the North Sea.

The second trio of Bostons flew low over the airfield at Bergen, where they dropped their bombs amid intense fire. A German battery damaged Lieutenant William G. Lynn Jr.’s plane, and it crashed a few miles north of the airfield. A second bomber in the flight was shot down by a Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter. The other six Bostons struck the airfields at Haamstede and Valkenburg. Bombs hit hangars, administrative buildings, and dispersal points, and an enemy fighter on the ground was set afire. The leader of the trio that attacked Valkenburg failed to open his bomb bay doors soon enough, so all the airfield received was a severe but brief strafing by the planes’ machine guns.

Eight of the surviving A-20s flew back to Swanton Morley, where their weary, shaken crews were debriefed and greeted by Generals Eisenhower and Eaker. But there was no sign of Captain Kegelman. Then, while the airmen, ground crews, and reporters clustered around the generals at the Swanton Morley control tower, a lone Boston was sighted limping low toward the airfield. Cheers went up, for Kegelman had managed somehow to bring his plane and crew home on one engine.

Building Up the “Mighty Eighth”

The raid was front-paged by London and American newspapers, and the San Francisco Call-Bulletin declared, “Yanks Join A.E.F. Raid.” Although the mission had inflicted only minimal damage on the Germans for the loss of two American crews and one RAF crew, General Arnold regarded it as a success because American airmen had been bloodied in action. But General Spaatz said the results justified his counsel against forcing action prematurely. He noted brusquely in his command diary, “The cameramen and newspapermen finally got what they wanted—and everybody seemed contented.” Arnold, meanwhile, pressed Spaatz for more USAAF operations and publicity.

At his London headquarters on the night of July 4, Eisenhower read the action report and considered that “the mission was well carried out.” He then scribbled across the report an immediate recommendation for Kegelman to receive the Distinguished Service Cross. He cited his “superior airmanship and extraordinary gallantry and coolness in saving the lives of his crew.” Spaatz pinned the nation’s second highest combat decoration on the smiling Kegelman on July 11. It was the first DSC earned by a member of the Eighth Air Force in World War II.

Kegelman also received a British decoration and was promptly promoted to major. Three of his men, Lieutenant Randall Dorton and Sergeants Bennie Cunningham and Robert Golay, were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

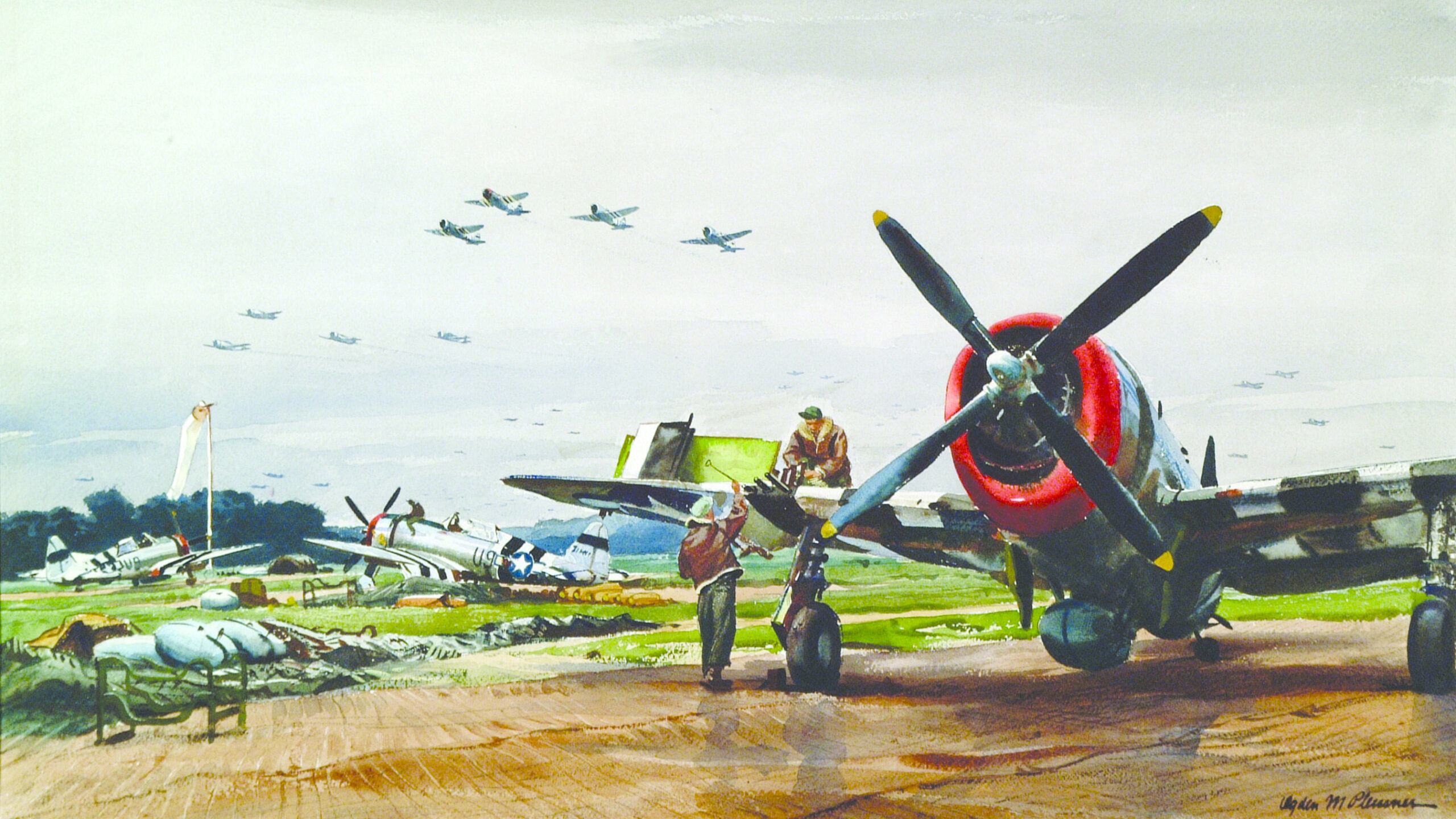

Six weeks after Kegelman’s raid, the Eighth Air Force launched its first heavy bomber mission. A dozen B-17s of Colonel Frank A. Armstrong Jr.’s 97th Bombardment Group took off from Polebrook Airfield in Northamptonshire on the afternoon of Monday, August 17, and bombed the German railroad yards in the French port of Rouen. General Eaker flew aboard the B-17 nicknamed Yankee Doodle as an observer. The following day, 24 Flying Fortresses flew in support of the ill-fated assault on the heavily defended port of Dieppe by Canadian infantry and British Commandos.

More B-17 and B-24 groups arrived in England, and the “Mighty Eighth” was able to mount increasingly destructive daylight missions against Nazi-occupied Europe and the German homeland, complementing RAF Bomber Command’s nightly raids. The enemy was soon being bombed around the clock.

Major Kegelman’s War

Flying Bostons from Molesworth, Major Kegelman’s 15th Bombardment Squadron took part with RAF units in low-level daylight raids on English Channel ports and German airfields through the summer of 1942. The squadron did not receive USAAF A-20 Havocs until September 5. Ten days later, and now under American colors, it was transferred to the RAF base at Podington, Bedfordshire, from where it flew a few more sorties.

Kegelman’s squadron was transferred on October 15, 1942, to the Mediterranean Theater, where it joined the Twelfth Air Force to support Operation Torch, the great, three-pronged Allied invasion of North Africa, on November 8. The squadron saw action in Tunisia with a USAAF Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter group and then was assigned to the Northwest African Training Command. Using Havocs and later North American A-36 Apache dive bombers (P-51 Mustang variants), the 15th Squadron’s veterans provided advanced training in ground support at several airfields during 1943. The squadron was disbanded at Mediouna Airfield in Algeria on October 1, and its crews and planes were absorbed into the 47th Bombardment Group.

Kegelman returned home in 1943 and was honored at a big celebration in El Reno attended by Oklahoma Governor Robert S. Kerr. The hero remained in the United States for a year training airmen, but he itched for more action. So, in 1944, he put in a request for active duty. Sent to the South Pacific that September, he was given command of a North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber group. But after several months of action, his luck ran out tragically.

While leading his group on a routine bombing run over the Japanese-held island of Mindanao in the Philippines on March 9, 1945, Kegelman’s wingman lost control and collided with his own B-25. The two planes plunged into the jungle, and Kegelman was killed at the age of 29. El Reno mourned its gallant son, and the local Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 382 was named in his honor.

Author Michael D. Hull is a frequent contributor to WWII History and writes on a variety of topics. He resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

The 8th Air Force is mentioned as flying on August 18, 1942, in support of the Dieppe raid. I don’t know how supportive that would be, seeing as the raid took place on August 19, 1942. I do recall that the RAF was reluctant to participate, beyond a very slight, token effort.

By the end of 1943, the outcome of World War II was a foregone conclusion. The Nazis were getting the hell kicked out of them on the Eastern front. On the Western front the Allies owned the skies and D-Day was just around the corner. If such was the case, why wasn’t D-Day launched from the North Sea instead of the Channel? All the Allies had to do was knock out all the bridges across the Rhine from the air. That would have prevented the Nazis in the West from crossing into Germany and the Nazis in the East could do nothing with the Soviets nipping at their heels and being chased back from Moscow to Berlin.

It would have been a cake walk then for the Allies and they could have just wlaked over to Berlin.

The Doolittle raid, in addition to being a morale booster, was also a prelude of what was to come against the Japanese in 1944. Left completely to his own devices, one can not help but wonder if Arnold would have started out small and worked his way up to the massive raids of later in the war. The precedent was Pershing’s wise schedule of entering combat in WW I only after thorough training and positioning of his forces thus reducing actual mass combat time to seven months.