By Captain Lee R. Mandel, Medical Corps, U.S. Navy

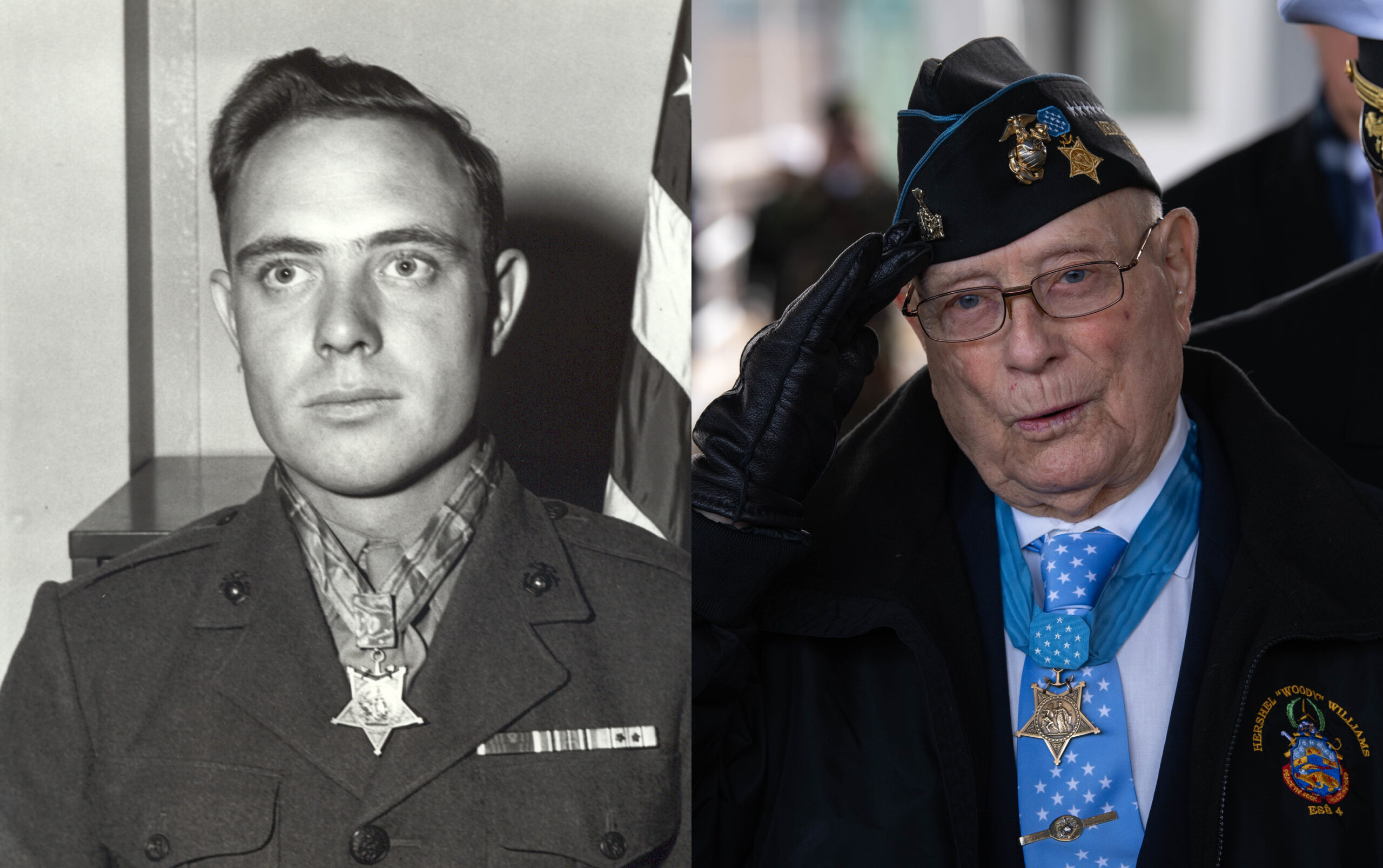

In modern naval history, there is perhaps no more colorful figure than the late Vice Admiral John Duncan Bulkeley. Throughout a career that spanned nearly six decades, Bulkeley’s name was synonymous with courage, decisiveness, and initiative. He first came into the public eye shortly after the onset of World War II. The daring raids on Japanese warships conducted by the PT boats of Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) Squadron 3 under his command provided some of the first instances of hope at a time in the war when the Japanese military machine seemed unstoppable.

Bulkeley will always be remembered for one of his most famous deeds, the rescue of General Douglas MacArthur, taking him, his family, and staff from Corregidor through 500 miles of Japanese-controlled waters to safety on the Philippine island of Mindanao. On August 4, 1942, Bulkeley received the Medal of Honor from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

It is commonly thought that Bulkeley received the Medal of Honor for rescuing MacArthur, but in fact he received it for his heroism during the entire period from December 7, 1941, to April 10, 1942. The citation notes “the remarkable achievement of Lieutenant Bulkeley’s Command in damaging or destroying a notable number of Japanese enemy planes, surface combatant and land based enemy forces during the four months and eight days of operation without benefit of repairs, overhaul or maintenance facilities for his Squadron, is believed to be without precedent in this type of warfare.” The citation further reads, “His dynamic forcefulness and daring in offensive action, his brilliantly planned and skillfully executed attacks, supplemented by an [sic] unique resourcefulness and ingenuity, characterize him as an outstanding leader of men and a gallant and intrepid seaman.”

The story of MacArthur’s escape from Corregidor aboard Bulkeley’s PT boat was first told in the 1942 bestseller They Were Expendable by W.L White, which MGM made into a 1945 movie. What is not as readily appreciated is that on the night the boats reached the safety of Mindanao, MacArthur sent for Lieutenant Bulkeley. He had another mission for him: Bulkeley was to find the president of the Philippines, Manuel Quezon, and bring him by any means necessary back to Mindanao so he could be flown to safety in Australia.

To appreciate the importance and significance of the assignment, it is necessary to examine the relationship between MacArthur and Quezon on the one hand and the importance to the United States of a strong alliance with the Philippine government on the other. The relationship of the two men served as a metaphor for the relationship between the two nations. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines in December 1941, both relationships were put to the ultimate test.

The relationship between Douglas MacArthur and Manuel Quezon was a long and largely cordial one. They met for the first time when MacArthur dined with Quezon and Sergio Osmena (also a future president of the Philippines) at the Army-Navy Club in Manila in 1904. When MacArthur was reassigned to the Philippines in 1922, Quezon was by then the speaker of the Philippine House of Representatives.

MacArthur served as Army chief of staff beginning in 1930, and in 1934 his term was extended for one more year by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. That year, Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act granting the Philippines commonwealth status as a prelude to the complete independence that would come in 1946. At that time, Quezon was the head of the Nacionalista Party and the clear frontrunner for the presidency. With Japan expanding its military influence in the Pacific, Quezon traveled to Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1934 to discuss the formulation of a U.S. military mission to protect the Philippines. He requested that General MacArthur be assigned to head the mission, and Roosevelt agreed.

In the spring of 1935, the new Philippine constitution was drafted. It provided for the creation of a new senior American government position, that of high commissioner, to replace the current ranking American position of governor general. The incumbent governor general was Frank Murphy, but by then Quezon was a loyal MacArthur supporter.

In May, Quezon wrote MacArthur a letter in which he shared privileged information. He confided to MacArthur that the U.S. government was going to offer the position to him. Quezon suggested that it might possibly serve all better if MacArthur took the military adviser job that he was slated for initially and then come to a decision about the high commissioner job after a while. He clearly favored the general but didn’t want to raise the idea himself. “Of course I did not discourage the idea fearing that my attitude might be misconstrued as opposition to your appointment. On the contrary, I stated that you are the best choice they could make and your appointment will be well received by the Filipino people.”

Although Roosevelt supported him for the high commissioner post and had promised it to him, under law MacArthur could not be nominated until he resigned from the U.S. Army. Soon, political intrigue surfaced between MacArthur and Murphy, further complicating the situation. Due to these circumstances, Roosevelt decided to appoint Frank Murphy as high commissioner and MacArthur as military advisor. In the fall of 1935, MacArthur sailed for the Philippines.

On December 31, 1935, Quezon wrote to MacArthur, contracting him to the position of military adviser to the president of the Philippines. His compensation was to be 36,000 pesos annually. The appointment was effective as of November 16, 1935. The following June, Quezon appointed MacArthur field marshal of the Philippine Army. This appointment caused much controversy in the United States, and his chief aide, Lt. Col. Dwight Eisenhower, tried to persuade him to refuse the title, stating, “It was pompous and ridiculous to be the field marshal of a virtually nonexisting army.”

MacArthur retired from the U.S. Army on December 31, 1937. About this time, Quezon was beginning to show signs of dissatisfaction with U.S. policy toward the Philippines, and by extension toward MacArthur. He began further agitating for accelerated Philippine independence, and when rebuffed, he considered seeking a policy of neutrality with Tokyo. He began cutting the Philippine defense budget, leading to a great loss of morale in the army. He began treating MacArthur with less respect as now he was no longer a U.S. Army general, but merely another Filipino civil servant.

Quezon clearly felt that MacArthur was no longer able to influence U.S. policy toward the Philippines. From this point on, the defense of the Philippines became the joint responsibility of native troops under Field Marshal MacArthur and the Philippine Department (American soldiers and Philippine scouts) under the command of an active duty U.S. Army general.

By mid-1941, the situation in the Pacific had greatly deteriorated. MacArthur was recalled to active duty as a major general (he was to attain five-star rank before the end of the war) on July 26, 1941, and was appointed commanding general of the U.S. Army forces in the Far East. In this capacity, he was charged with the defense of the Philippines. President Quezon quickly put aside his previous defeatism and once again warmly embraced the general, claiming, “All that we have, all that we are, is yours.” He then broadcast to the United States an unequivocal message: “The stand of the Philippine Nation is clear and unmistakable. We owe loyalty to America and we are bound to her by bonds of everlasting gratitude. Should the United States enter the war, the Philippines would follow her and fight side by side.”

The following day, he wrote to MacArthur to congratulate him on his appointment. He signed the letter with the salutation “Very affectionately yours,” a marked difference from his prior correspondence to the general which he always ended with “respectfully” above his name.

On December 8, the Japanese invaded the Philippines. Quezon steadfastly expressed his loyalty to the United States and to MacArthur, in one letter referring to himself as “the best friend you have ever had.” He urged the general not to take any unnecessary risks, stating that if something were to happen to him “the effect upon the armed forces and the civilian population of the Philippines would be, to say the least, most demoralizing.”

Almost daily as December passed, both MacArthur and Quezon grew increasingly frustrated as the Japanese swept across the Philippines and advanced on Manila. Promises of military aid continued to emanate from Washington, but the reality was that there would be none forthcoming. On December 24, MacArthur and his staff and Quezon and his staff were evacuated from Manila to the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay. By then, Quezon was openly expressing harsh criticism of the failure of America to come to the Philippines’ assistance and its “Europe first” sentiments.

While on Corregidor, Quezon’s bitterness toward his perceived abandonment by the United States grew. Upon hearing a broadcast of a fireside chat on January 22, 1942, during which Roosevelt unequivocally outlined a strategy of defeating Berlin and Rome before turning attention to the Pacific War, Quezon exclaimed, “How typical of America to writhe in anguish at the fate of a distant cousin, Europe, while a daughter, the Philippines is being raped in the back room!” His mounting anger was evident in the letter he wrote to MacArthur on January 28, 1942.

In this letter Quezon first refuted the claim of a Japanese radio broadcast that a new Philippine government had been formed by prominent Filipinos sympathetic to Japan. He reiterated his loyalty to the United States. His tone then shifted to bitterness toward the Roosevelt administration for its apparent abandonment of his country. “How long are we going to be left alone? … It seems that Washington does not fully realize our situation nor our feelings which the apparent neglect of our safety and welfare have engendered in the hearts of people here.” He castigated Roosevelt for not even responding to his messages asking for assistance and ended by once again haranguing MacArthur, “I am confident that you will understand my anxiety about the long-awaited reinforcements and trust you will again urge Washington to insure their early arrival.”

As the situation on Corregidor deteriorated, Quezon agreed to be evacuated with his family to one of the unoccupied Philippine islands with the expressed purpose of keeping up his people’s morale and support of the United States. He told Mac-Arthur that he was leaving with a heavy heart, “for you and I have not only been friends and comrades; we have been more than brothers.”

Shortly after this, MacArthur was ordered by Roosevelt to break out of Corregidor and escape to Australia. Knowing that the Japanese were determined to prevent his escape, he sent for the young naval officer who had already distinguished himself in combat, Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley. Bulkeley would plan and execute the daring escape through largely uncharted Japanese-controlled waters to Mindanao; the general would be flown from the Del Monte airstrip to Australia.

The four PT boats of the expedition left Corregidor on the night of March 11 and arrived in Mindanao on the morning of March 13. Upon docking, MacArthur said, “Bulkeley, I’m giving every officer and man here the Silver Star for gallantry. You’ve taken me out of the jaws of death, and I won’t forget it.” Bulkeley was then given operating orders to work under Brig. Gen. William F. Sharp, commander of the U.S. Army forces on Mindanao. He was directed to “conduct offensive operations against the Empire of Japan in all waters north of Mindanao.” To the 30-year-old Bulkeley, with his fleet of four PT boats, that made him “commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet,” and he would conduct himself accordingly.

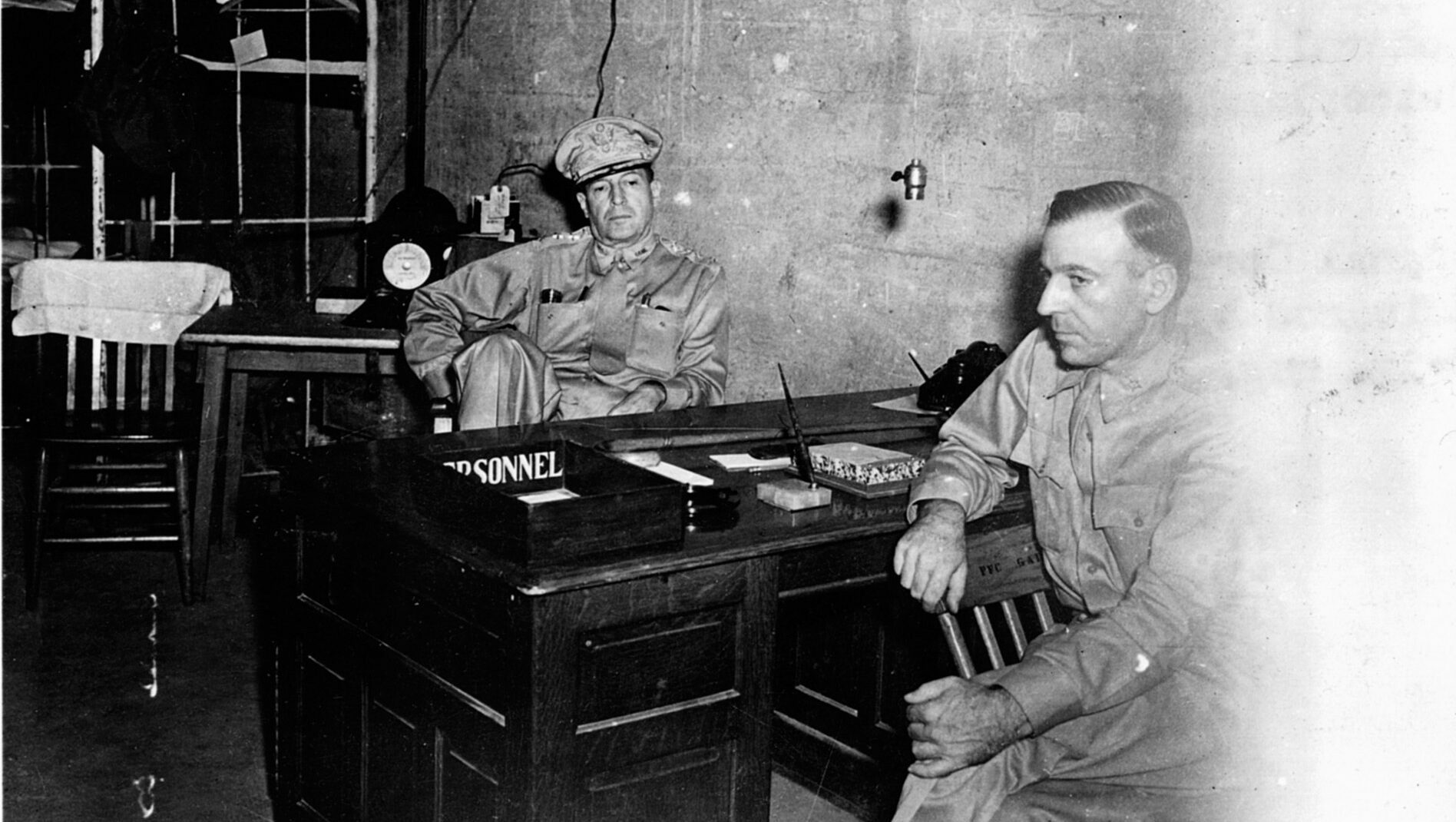

On the afternoon of his arrival, MacArthur received extremely unsettling intelligence reports. In Washington, the increasingly vocal discontent of Manuel Quezon was being closely monitored and his loyalty had come under question. Japanese destroyers were headed to the island of Negros were Quezon was hiding, and it was felt that it was highly likely that they would attempt to capture him and set up a puppet government. It was deemed imperative to U.S. interests that Quezon be brought out of the Philippines and taken to Australia where he could begin to set up a government in exile. That night, MacArthur again sent for Bulkeley, whom he called “Johnny Bulkeley, that bold buckaroo with the cold green eyes.”

MacArthur then began to describe the mission to Bulkeley. He was to go to the port of Dumaguete on the island of Negros, approximately 100 miles away. He would find President Quezon and his family, Vice President Osmena, and several cabinet members. He would then bring them back to Mindanao so they would be flown to Australia. The task could be very risky. In addition to the fact that the waters around Negros were largely uncharted, there were seven Japanese destroyers in the vicinity also looking to capture Quezon.

In They Were Expendable, Bulkeley describes being informed of the assignment in one bland sentence in which he simply states he was called in and given the task by the Army. In later years, he would elaborate on the context of the tasking. When Bulkeley met with MacArthur, where he found the general extremely agitated and angered by the situation. After giving Bulkeley his assignment, he stated, “I don’t care how you get him here, just do it!” In his usual no-nonsense style, Bulkeley would recall thinking, “If General MacArthur wanted Quezon back there, then I intended to bring the son of a bitch back—one way or the other.”

MacArthur then introduced Lieutenant Bulkeley to Don Andres Soriano, an aide to President Quezon, who would serve as interpreter and guide to help find the president. Bulkeley instinctively took a disliking to Soriano as he was uncertain of the guide’s loyalty to the United States—a suspicion that would prove to be unfounded. As he shook hands with both men, MacArthur said, “Don’t forget Johnny, bring him back—by whatever means is necessary!”

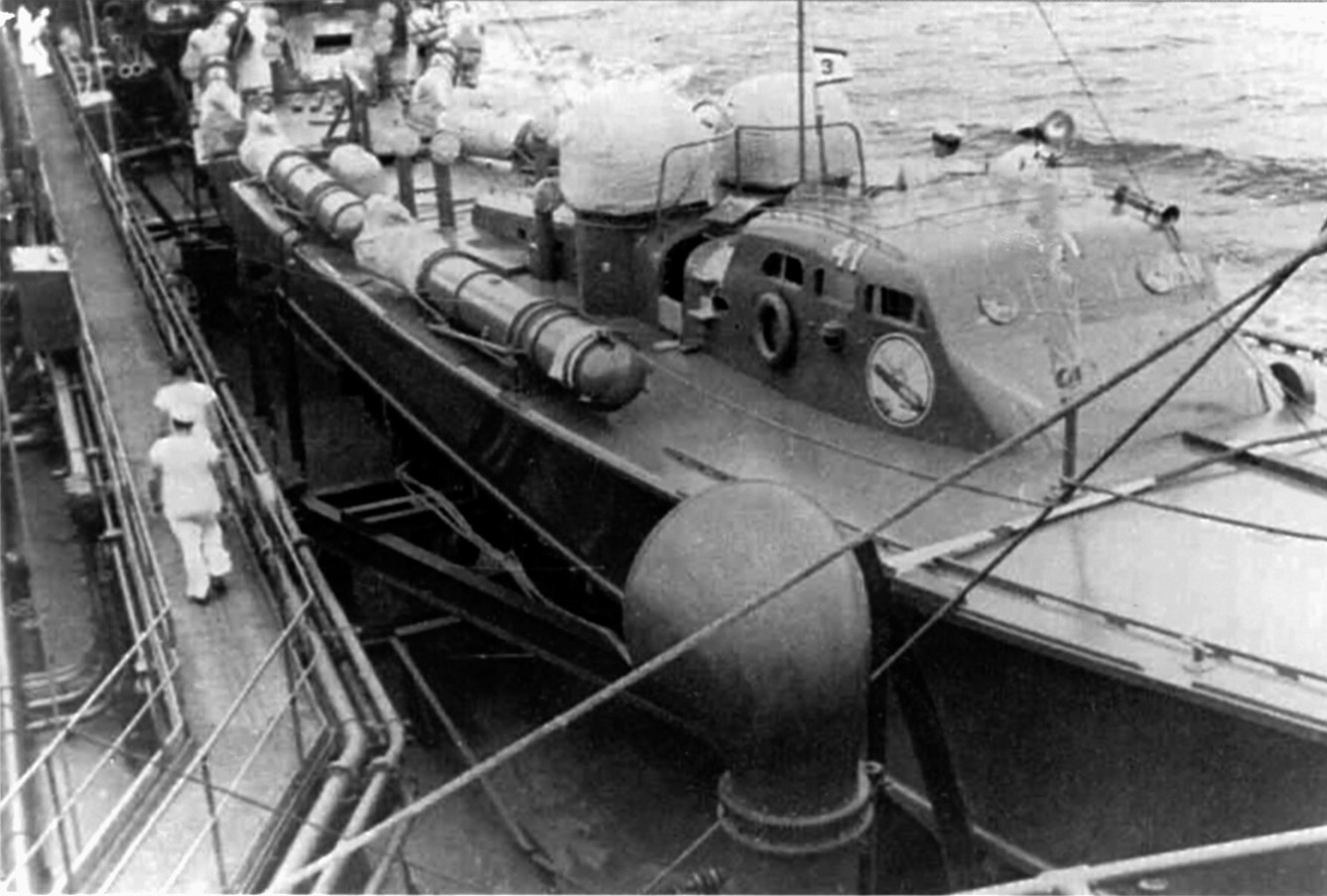

At 7 pm that night, Bulkeley got underway in PT 41, accompanied by his only other usable boat, PT 35. Shortly after leaving, the Americans spotted a Japanese destroyer, and the two boats hid behind a small island until the destroyer had passed beyond them. Three hours later, they arrived at Dumaguete. Without any charts, they found the water to be dangerously shallow. Rather than risk their boats, they anchored out, and Bulkeley, Soriano, and two other crew members waded ashore. All were armed, Bulkeley himself carrying a machine gun. Before leaving the boat, Bulkeley had taken aside the other two crew members and told them to shoot Soriano if it appeared that he had led them into an ambush.

President Quezon was not waiting there as expected. Instead, they came upon a local constable who told them that the president had left earlier in the day. He then refused to disclose his location to Bulkeley. Using persuasion in the form of a machine gun muzzle to the constable’s head, Bulkeley got the man to reveal that Quezon had gone to the village of Bais, about 25 miles up the coast. The men returned to their boats and proceeded to Bais. Bulkeley ordered PT 35 to patrol the area while PT 41 tied up at the small pier, and he and Soriano went ashore.

After learning that Quezon was staying in a hut several miles from the pier, Bulkeley commandeered two cars, and he and Soriano sped off to the designated location. There, Soriano called out twice in Spanish to the president before a light came on inside the house. Quezon then appeared in the doorway alone.

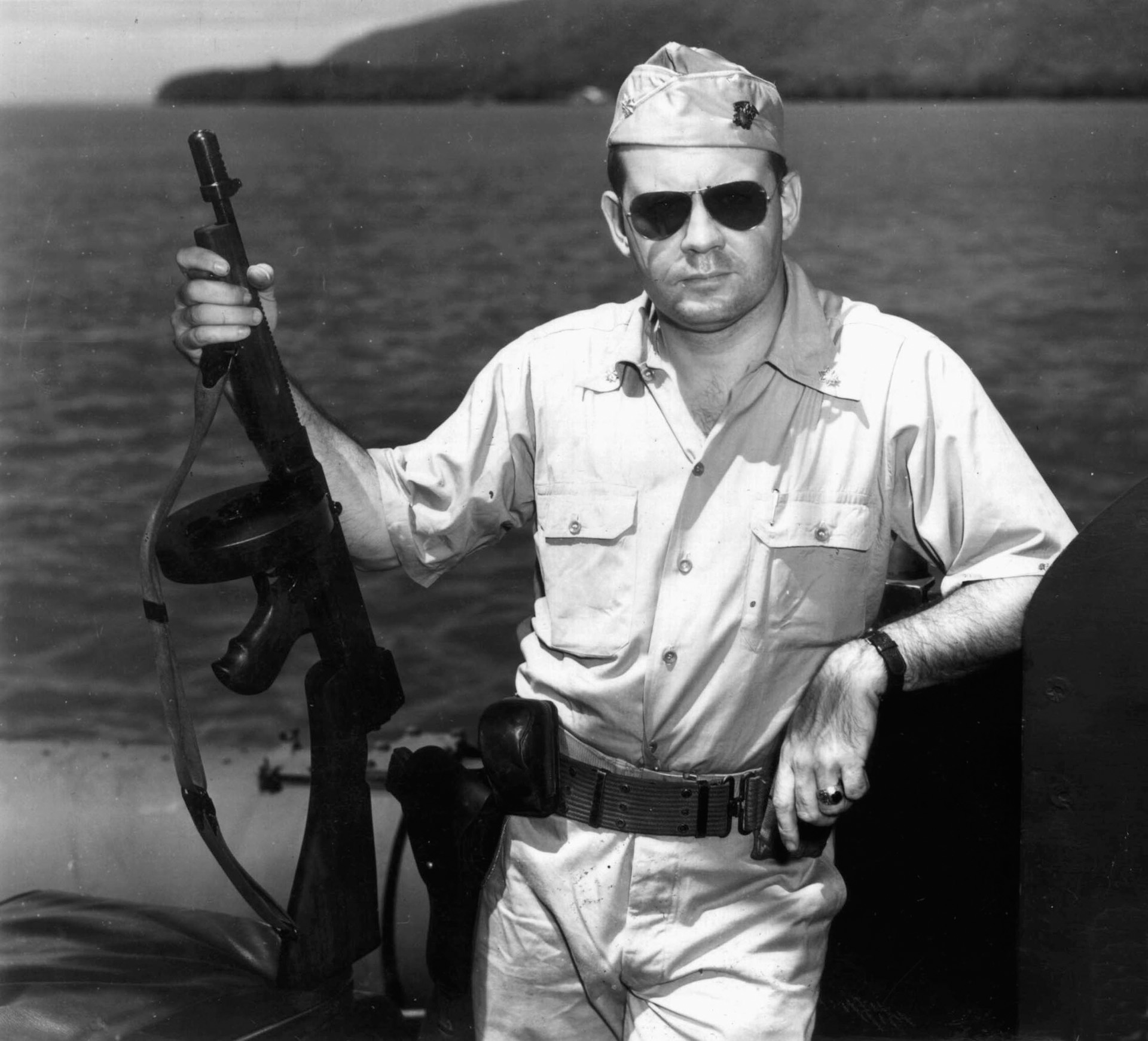

The image of John Bulkeley must have terrified the president. Bulkeley was not in uniform, had an unkempt beard, wore a bandana over his long hair, had a trench knife and a pair of pistols in his belt, and was brandishing a machine gun. He also carried no identification, either military or civilian. In his own words, Bulkeley would recall that he “probably looked disreputable to Quezon.”

Bulkeley lost no time in telling Quezon that his mission was to bring him and his family, Vice President Osmena, and their staff back to Mindanao so that they could be flown to Australia. He proposed leaving immediately so that they would still have several hours of darkness to travel across the open seas. To Bulkeley’s fury, Quezon refused to leave. He cited a telegram he had received earlier in the day from General Jonathan Wainwright, MacArthur’s successor in the Philippines, stating that such a trip would be too risky given the Japanese destroyers in the area.

Bulkeley did not let on that he was aware of Quezon’s vacillating loyalty to the United States. In the initial description of this encounter written in 1942, Quezon listened to Bulkeley and quickly decided to go with him. This very superficial account was written during the critical early days of the war. The nation needed heroes, and the war effort needed harmony among allies. Quezon most likely would not have been portrayed as anything less than a fiercely loyal American ally. The reality of the encounter was quite different.

In a letter to the director of the MacArthur Memorial, Bulkeley stated that he pointed out to Quezon the repeated treachery of the Japanese and described the Japanese idea of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere as “hogwash.” He told Quezon that he would merely be a puppet ruler and that Philippine independence was the furthest thing from the minds of the Japanese government. In saltier language in another interview, he stated, “I stared hard at the bastard and minced no words, reminding him of repeated Japanese treachery in the Far East.” Another subtle convincer was pointing his machine gun at the president’s head. Shaken, Quezon then agreed to go.

Bulkeley quickly rousted up Quezon’s family, Vice President Osmena, a general, and two cabinet officials, piled them into the “borrowed” cars, and drove them back to the pier at Bias. There they learned that PT 35 had struck a submerged object and had to be beached. The crew from PT 35 would have to go back on Bulkeley’s PT 41. On the dock, more members of Quezon’s cabinet appeared, along with a huge amount of luggage. Included in this were seven mail sacks containing about $15 million in American currency.

The Filipinos began arguing over who would sit where in the boat and what luggage would be taken. Losing patience, Bulkeley shouted above the chaos, “All right, everybody get aboard—and leave those goddamn suitcases on the dock!” The situation then worsened when President Quezon announced that he had changed his mind and was not going. There are no surviving accounts of exactly what Bulkeley next said to him, but after a shouting match Quezon reluctantly agreed to go.

Less than an hour after PT 41 was underway, the sea turned violently rough. Soon, all of the passengers were seasick and vomiting. Shortly afterward, a huge wave slapped against the side of the boat, knocking two torpedoes loose in their tubes where they instantly started a hot run—a terrific hissing of compressed air, with the propellers grinding. Bulkeley and two of his torpedomen began working feverishly to dislodge the torpedoes from the tubes before they detonated. While a puzzled Quezon looked on, the men were successful in getting the activated torpedoes launched.

After this episode, Bulkeley and Quezon were soon at loggerheads again. The operational orders were to arrive at Mindanao at Cagayan on the western side of Misamis Bay. Quezon announced that he wanted to go to the port of Oraquito on the eastern side of the bay. Bulkeley emphatically spelled out what his orders were, but Quezon kept insisting on Oraquito and was preemptive about it. Bulkeley, with Quezon’s eyes fixed on the ship’s compass, finally sent a radio message to General Sharp reporting that they would instead be arriving at Oraquito at dawn. At first light, PT 41 tied up at the pier at Oraquito. Waiting to greet them were General Sharp and an Army honor guard, who escorted President Quezon to the Del Monte airfield where he and his staff (and his mail sacks of cash) were flown to Australia. John Bulkeley’s mission for MacArthur was completed.

Bulkeley and Quezon were to meet again soon after, this time under very different circumstances. On April 13, General Sharp conveyed orders from MacArthur that Bulkeley was to leave the Philippines that night, flying in a Boeing B-17 bomber from the Del Monte airstrip to Australia. He arrived wearing a jacket, pants, and sneakers without any other possessions and no money. An Australian family took him home as their guest, and Bulkeley proceeded to sleep for 36 hours.

Shortly afterward, Bulkeley was invited by MacArthur to a luncheon honoring Quezon, who would be leaving shortly for the United States where he would be heading up the Philippine government in exile. It was a dramatically different John Bulkeley who attended—he was clean shaven with regulation haircut and wore the uniform of a United States Navy lieutenant.

Quezon was jubilant at the reception. He proceeded to address the meeting, describing in detail how he had been rescued by “an old American sea wolf.” As Bulkeley listened, somewhat confused by this reference, Quezon finished his detailed narrative by turning to him and saying, “I want to express my sincere appreciation to your father, the sea wolf, and commend him on his great courage and seamanship.”

The entire audience, led by General MacArthur, erupted into laughter. When he realized his mistake, Quezon joined in on the laughter. He was to use the story of his mistake to his public relations advantage the following month when he gave his first press conference as the Philippine president in exile. On May 19, 1942, he held forth over the Washington press corps and revealed the story of his rescue to the American public. He was a master showman and was in excellent form that day.

“I am ready to leave Negros when here comes a message from General Wainwright for me to cancel my trip and remain right there. The sea around you is filled with Japanese destroyers it says. It was stormy night. Suddenly my aide, Colonel Soriano, appears out of darkness and introduces me to a man who looks like a fierce Spanish pirate, a sea wolf, with a formidable black beard and a cloth tied around the head like a turban.”

Pausing for effect, he leaned forward and revealed the pirate’s name: Lieutenant John Bulkeley. After pausing again, Quezon continued. “‘I most certainly urge you, sir, to take my boat to Mindanao’ the pirate told to myself. ‘By gosh’ I said to myself, ‘this is the right man!’ So I ignored General Wainwright’s order and got into the PT boat. A month later, a young naval officer was presented to me in Australia. It was Lieutenant Bulkeley. Only this time he had no beard. He was no pirate. In fact he looked like a young boy. ‘Goddamn’, I told him, ‘if I had seen your face I would have not gone with you!’”

During his mission for MacArthur, one that could be described as either a rescue or a kidnapping, John D. Bulkeley displayed many of the qualities for which he would become famous. His bravery, resourcefulness, and superb seamanship were showcased along with his dogged determination to complete his mission. His willingness to ruffle feathers and his salty demeanor were readily apparent even at this early stage of his career. He would be recalled to active duty the moment he reached statutory retirement age and go on to complete a distinguished career that spanned nearly 59 years before retiring on August 25, 1988. Shortly before his death, in a taped interview, he was asked to sum up his life in one sentence or phrase. Without hesitation, he succinctly replied, “Interesting, fascinating, and useful; to the United States and myself.”

Captain Lee R. Mandel served as personal physician to Vice Admiral John D. Bulkeley. He is currently the Force Medical Officer for the Commander Naval Air Forces, U.S. Atlantic Fleet in Norfolk, Virginia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments