By Chuck Lyons

During World War II, one American intelligence unit was so secret it was known only by its post office box number, 1142. Although it was located only 11 miles down the Potomac from Washington, D.C., in a complex surrounded by multi-alarmed fences, most members of Congress and even the American military leadership knew nothing of its existence.

Known officially as MIS-X (Military Intelligence Service-X), the unit was created in October 1942. It fought the war on what has been called “the barbed wire front.”

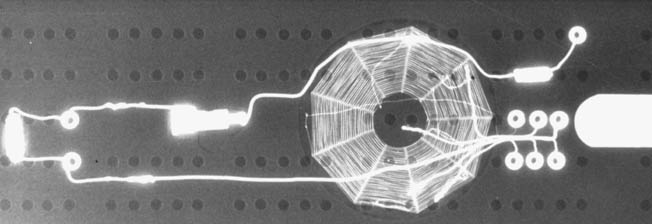

The unit sent aid packages to POW camps, but those packages also included carefully secreted compasses and tissue paper maps hidden in the handles of shaving razors and hair brushes, cardboard checkerboards that could be steamed apart to reveal documents layered inside them, radio parts hidden in baseballs and in cribbage boards, pens in pipe stems, and other items all intended for a single purpose—aiding in the escape and avoiding the recapture of American prisoners of war.

Procuring The Tools of Escape

MIS-X also contacted American manufacturers and, without telling them exactly what they were doing or why, recruited them to assist by producing such things as “peel open” playing cards in which small maps and other documents could be hidden. The Gillette Razor Company, for example, joined in by magnetizing its double-edged razor blades in such a way that, when balanced on a piece of string, the “G” in Gillette pointed due north, creating a handy compass. A Connecticut company manufactured and hid even smaller compasses in the buttons it manufactured for U.S. military uniforms.

At one point in 1944, MIS-X was sending out 120 parcels a day to German POW camps but was forced to reduce its output when coded messages from the camps pleaded with it to do so. The POWs were simply running out of room to hide things.

Though the exact number is in dispute, according to some estimates as many as 130,000 U.S. troops were captured and became prisoners during World War II, with almost 94,000 of them held by the Germans and 27,000 by the Japanese. Germany also interred 4,700 American civilians, while Japan imprisoned 14,000. Almost 11 percent of the American POWs, 14,072 to be exact, died in captivity.

British Intelligence Paved the Way

Another sizable group escaped or at least tried to escape, and by the end of the war 737 of these men had successfully slipped out of German POW camps and avoided recapture. The number of attempted escapes that resulted in recapture is unknown but is certainly many times greater than the number of successful ones, and MIS-X aided in almost all these attempts. Interestingly, much of the work done to aid these men had begun with the British.

Britain entered the war in 1939, and in June 1940 some 50,000 British troops were captured fighting in rearguard actions at the Battle of Dunkirk. Sir Gerald W.R. Templer, then an acting lieutenant colonel in military intelligence, suggested that some provision should be made to make the men’s confinement more comfortable and at the same time aid them with any escape plans they might have. He also suggested that some training should be provided to all His Majesty’s troops on how to act if captured. British officials at the time were aware that a generation earlier during World War I a large number of British prisoners had escaped from German POW camps without any outside assistance.

MI-9 & MIS-X

What could be done to help with escapes during the current war?

Based on Templer’s suggestion, the British created MI-9 (Military Intelligence, Section 9), which first provided training for soldiers in the event that they were captured and then expanded to include aiding with escapes. When the United States entered the war in late 1941, the British willingly shared with U.S. Intelligence what capture and escape information they had gathered and developed. MIS-X was established as a result of this sharing of information.

Meanwhile, the United States was also in the process of establishing a center to detain and interrogate enemy POWs who were suspected of possessing vital military information. That center was to be located at an abandoned Civil War and World War I military post known as Fort Hunt, 11 miles south of Washington on the Potomac River. The area had once been farmed by George Washington when he resided at his nearby Mount Vernon estate and was at the time World War II began in use as a local picnic area.

Beginning in April 1942, buildings were erected on the site, and the facility was staffed with some 400 military personnel, many of them well educated, fluent in European languages, and familiar with Europe and its customs. A number of them were Jewish. Most were the last to receive their assignments at the end of basic training. Usually they were told to proceed to Washington and wait at a particular intersection, where they were then picked up and taken to the super-secret Fort Hunt.

POW Activity in Fort Hunt?

Local residents of the Fort Hunt neighborhood were of course aware of military activity in the area and watched as buses with blackedout windows passed back and forth, but they were kept unaware of the camp’s true purpose. The idea was put about that it was just another POW camp, one of many that were blossoming throughout the country at the time.

In October 1942, another unit was tucked into the camp, a unit so secret even the post commander, who of course knew of its existence, was unaware of its actual purpose.

That unit was MIS-X. Over the years of its existence Fort Hunt also housed units that studied captured enemy documents, publications, and images, and served as a facility for Operation Paperclip, the effort to bring captured German scientists to the United States, including Werner von Braun, who would gain fame for his work on the U.S. space program.

MIS-X consisted of five subsections dealing with the interrogation of successful escapees about any military information they may have picked up and on what had worked and what had not worked in their escapes. Its work also involved correspondence with POWs, determining camp locations, training and briefing, and technical matters, while areas were in charge of secreting objects in aid packages, developing miniature cameras, and the like. MIS-X had also been given the responsibility of instructing air crews on what to do if shot down in enemy territory, how to act if captured, and how to escape. Further, the unit prepared and distributed escape kits and carried on coded correspondence with POWs.

Barbed Wire: The New Enemy Front for POWs

It was immediately decided that training should be given to all military personnel destined for combat areas. They were made to understand that if captured it was their duty to be an “irritant constantly occupying and distracting [their] captors through escape efforts [and] striving through any means possible to relay information to [their] comrades.” The POW was not to be a passive victim, but was in fact to consider himself still an active combatant.

“The POW was to think of barbed wire as his new front,” wrote Lloyd R. Shoemaker, who was an MIS-X operative during the war and wrote about the unit in 1990.

By November 1942, MIS-X was operating and had begun delivering escape and evasion instructions. Those instructions included requirements that servicemen wear heavy shoes in case they had to walk long distances, that they carry escape kits containing such things as mirrors, bandages, fish hooks and line, a tiny compass, and tissue paper maps of known POW camps, that they not carry anything on their persons—such as personal letters—that could identify their unit’s location, and that they were to seek out and aid an escape organization existing in any camp to which they were sent.

An escape manual was also produced that detailed such things as how to avoid capture, how to resist interrogation, favored European escape routes, and the like. Among the “salient factors” the escapee needed to make a successful escape, the manual sensibly listed “luck,” “good feet,” and “common sense.”

Letter Codes To Track The Package of Shipments

Although training and instruction could be given beforehand, many of the MIS-X escape aids could not. They were of no value if they did not arrive at the camps to which they were sent. Likewise, MIS-X needed to know whether they actually arrived at their destination. Further, the POWs in the camps needed to know which items had been sent and where they were hidden.

To solve these problems, a simple letter code was developed. If a POW writing home were to date his letter, for example, March 13, 1943, that would be an indication there was no coded message involved. Dating it 3/13/43, however, would indicate there was such a coded message. Clerks working with the government censorship office scanned all incoming mail from POW camps and separated any that came from known “Code Users” or “CUs” as they were called. Those letters were then routed to Fort Hunt, where they were steamed open, decoded, and recorded. They would then be closed again, slipped back into the normal flow of mail, and continue on their way to parents, girlfriends, brothers, and sisters without the recipients being aware the correspondence had ever been opened and read.

As the training of men to serve as briefers in escape and evasion tactics progressed, one or two men were selected from each battalion and were trained in the letter code. If captured, it was their job to remain in contact with the U.S. military through the regular mails using the new code. These men were so carefully selected, Shoemaker wrote, “that not one ever broke security. Amazingly, MIS-X personnel had been able to maintain greater secrecy that those associated with the atomic bomb project.”

By the end of the war, some 7,724 men had been taught the code. None were ever uncovered, and the fact that such a code system was in use was never discovered by the enemy. Through these men, the U.S. military was able to keep in regular contact with virtually every German POW camp. That correspondence also allowed POWs to send back what knowledge they had gained that could aid in the war effort.

Some Setbacks With Early Shipments

By 1943, for example, MIS-X received coded information from an air officers’ camp some eight miles south of Berlin. The coded message read: “Fort emerge forward hatch not working right. Many can’t get out.” The message alerted the Army Air Forces that the forward hatch on the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber was malfunctioning and preventing evacuation of the plane in emergencies. Within 24 hours repairs had begun throughout the air service. Another message was forwarded to all camps in France warning escapees to avoid the city of Tours, which had heavily policed checkpoints. Another warned of a fake Red Cross inspector who was trying to solicit information from prisoners.

By then parcels had begun to roll into the European camps, but not without some setbacks. Some were humorous, like the operative who was accused of being a hoarder and had a tomato thrown at him when he emptied a College Park, Maryland, grocery of canned fruit for aid packages. Others were more serious, such as the MIS-X operative who was actually detained by the FBI and accused of being a German spy after he tried to buy several identical cameras in a Baltimore store.

But on the whole things went well. Rather than use Red Cross parcels for its shipments, which would have imperiled the nature of the Red Cross’s work, MIS-X created fictional agencies, groups such as the War Prisoners Benefit Foundation and Servicemen’s Relief. Three types of packages were sent through each of these agencies: food parcels containing such things as the canned fruit purchased in College Park but no escape aids, clothing, and recreational parcels. It was in the last two kinds of parcels that the escape aids, maps, documents, compasses, civilian clothing, wire cutters, German cash, radio parts, and small cameras, even German uniforms and German-lettered typewriters, were secreted.

A Spike in U.S. POW Numbers

In one instance, a camp requested a hand-operated printing press complete with type, ink, and paper, while another asked for “small caliber guns and ammo for close sniping.”

In mid-1944, with the Normandy invasion, the number of U.S. troops taken prisoner spiked. About that same time, Hitler issued his well-known order that created “Death Zones” around munitions, armament, and experimental plants in Europe. His order mandated that any escapee captured in these zones would be immediately executed. In the face of this order, MIS-X informed prisoners that they were no longer expected to escape.

By late October 1944, MIS-X had suspended sending parcels to Europe altogether after being told the Pentagon expected the European war to be over by Christmas. In addition, as Allied troops began closing in on Berlin, German roads and railways were reduced to shambles, making the shipments of parcels almost impossible. At Fort Hunt, activity ground to a near halt with some time being given to aiding POWs in Japanese camps.

MacArthur & The Japanese Made MIS-X Work More Difficult

The Japanese, however, were much stricter about the number of parcels allowed in their camps. In addition, General Douglas McArthur, the Pacific Theater commander, allowed intelligence operations in his area only if they were under his command, which interfered greatly with the work of MIS-X. The unit did little more than design and issue escape kits for those serving in the Pacific.

With little to do, the MIS-X staff then spent days worrying about the POWs they had been aiding and had grown to know over the previous two years.

On May 8, 1945, the war in Europe ended. Almost immediately escape committee members from the various liberated POW camps were cleared in France and flown to Washington for debriefing.

On August 14, the war in the Pacific ended. Six days later, MIS-X received an order to “burn all your records” and artifacts within the next 24 hours. It took 36 hours.

In that time, MIS-X staff worked over three 30-gallon military trash cans, wadding and burning paper records, breaking up doctored game pieces and game boards, and cutting radio wires into small pieces. Unaltered games, blankets, razors, and clothing were donated to Walter Reed Army Hospital. The Salvation Army was called to remove all remaining food items.

“And with that,” Shoemaker wrote, “MIS-X was shut down.”

Currently, the U.S. National Park Service is conducting an oral history project about MIS-X and its activities at Fort Hunt. The project is also interested in obtaining copies of papers, letters, photographs, and artifacts connected with MIS-X.

Hi, I am looking at the MIS-X from the Australian perspective. Is the US National Parks project still being undertakem?

Regards

David