By Miles Hood Swarthout

When Brig. Gen. Nelson A. Miles finally met Geronimo in Skeleton Canyon, four miles above the Mexican border in southeastern Arizona Territory on September 3, 1886, the U.S. Army’s famous Indian fighter wanted to impress upon his fabled foe the white race’s superior advantages—their steam trains that could move troops rapidly

about the country; their Hotchkiss rifles that the Apache had never used before; and especially the general’s new telegraph system. The 60-year-old renegade was familiar with trains and rifles, and years before the shrewd Apaches had figured out how to cut the white man’s talking wires and splice the cuts back together with rubber bands or strips of rawhide and hide them up in trees, making the broken telegraph wires devilishly difficult to track down and fix.

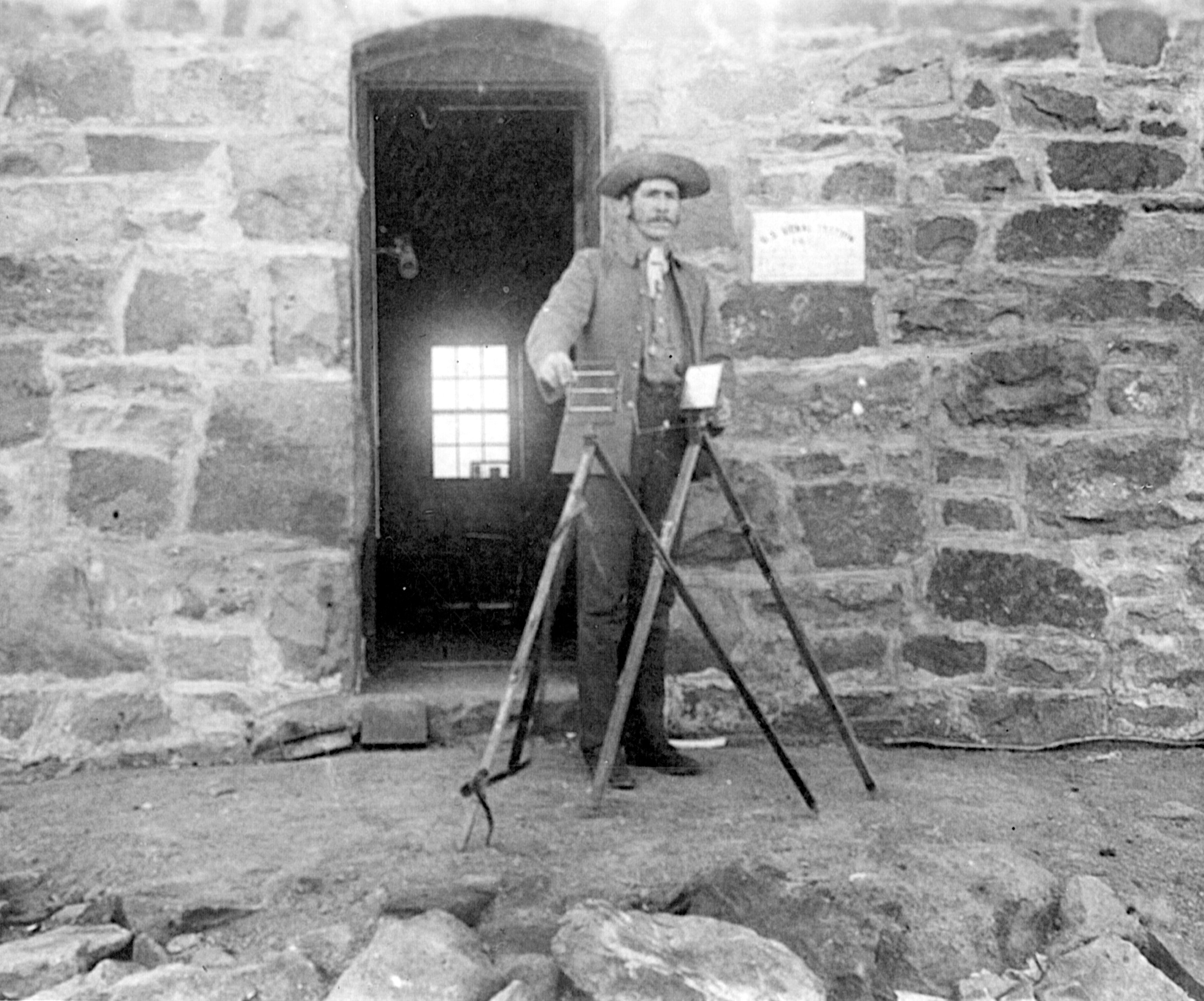

What Geronimo pretended not to be familiar with, though, was the general’s heliograph equipment—a mobile unit Miles was using to stay in touch with his southwestern forts, whose soldiers were patrolling for remaining hostile Apaches. To demonstrate his new communications system, Miles had his enlisted operator tie three sticks together for a makeshift tripod and aim it at a mountain peak 15 miles away. General Miles told Geronimo that he was now going to talk to Fort Bowie, 65 miles to the north. Geronimo had earlier sent his brother to the fort as a hostage to guarantee that he would surrender to the Army again. Now Geronimo wanted to know if his brother was all right.

Miles had his heliograph operator flash Fort Bowie and ask the officer in command, Major Eugene B. Beaumont, if Geronimo’s brother was there. He then told the Apache war chief they’d have to wait, for the inquiry with a reply would have to be passed through three heliograph stations, repeated six times.

While they waited, Geronimo told Miles that he had observed these flashes on mountain heights before and believed them to be spirits. The Apache had therefore avoided them by going around these points on the mountains, not realizing it was a subtle power used by his enemies, who were themselves located up on these lofty points for observation and communication. The answer came back that Geronimo’s brother was at Fort Bowie and waiting for him to come. According to the general, Geronimo was so awed by this trick that he sent one of his warriors out to Naiche’s camp to say that there was a power here he couldn’t understand and to come quick!

Naiche, Cochise’s second son and the current chief of the fighting Chiricahua band of Apaches, did come in with his followers to Miles’ camp then, but according to 1st Lt. Charles B. Gatewood’s military account and Geronimo’s own autobiography, Naiche was grieving for his brother, who had gone back to Mexico to fetch a favorite horse and had not returned. Thinking his brother killed by the Mexicans, Naiche didn’t wish to meet with General Miles right then, but he’d made a promise to Lieutenant Gatewood that he would talk with the general about surrendering, so reluctantly went in to meet with the ranking officer in the Territory.

It must be remembered that Nelson Miles was writing this for his own autobiography, Personal Observations and Recollections. As a general in the post-Civil War Army, legendary for his vanity and relentless self-promotion, Miles’ recollection of his first heliograph demonstration to the famed warrior perhaps had more than a touch of fiction to it. Nelson A. Miles was also known as the only general in the U.S. Army besides George Armstrong Custer to design his own uniforms, being especially partial to gold braid, sashes, and large epaulets.

Geronimo was a wily veteran of the Apaches’ 26-year war against the white man and undoubtedly knew these new sun-flashing devices were for passing messages between military units. The Apaches themselves had used bits of mirror and shiny pieces of metal to flash warning signals among their own bands for decades, not to mention using smoke signals. As early as August 1885, wrote Odie B. Faulk in The Geronimo Campaign, C.A.P. Hatfield, an Army officer in that campaign, reported that “Apaches had taken a position on a conspicuous, lofty mountain called Sierra Azul, in Sonora, Mexico, about 75 miles southeast of Fort Huachuca. The Indians kept up a brisk signaling to parties in Arizona every night and could be plainly seen.”

When General Miles took over after Geronimo had disgraced General George Crook by fleeing from his prior surrender parley in late March 1886, Miles, with General Philip Sheridan’s blessing, instituted three major changes in the war with these Apaches. First, he asked for a large influx of troops, shipping several thousand more soldiers in cavalry and infantry units out to the Arizona and New Mexico Territories. Miles thus commanded over five thousand men, one quarter of the entire post-Civil War professional Army in this final campaign, against the roughly one hundred wild Apaches still on the loose.

Second, because neither Sheridan nor Miles trusted the Apache scouts whom Crook had used so extensively to fight his battles, he got rid of them. Both generals suspected Apache scouts were passing intelligence and ammunition along to their renegade relatives in the brush, warning them in advance and even deliberately misleading their regular Army officers, who were trying to track down Geronimo. True or not, these top military men took out their frustrations on the scouts, believing these tame Apaches weren’t catching Geronimo and his renegades to preserve their scouting jobs and keep their wilder kin alive. Thus Miles immediately disbanded the Apache scouts and only retained some “river” Indians, Yumas and Wallapais, for scouting duties with the mostly white troops. Nelson Miles felt his younger, fitter Caucasian troopers were the physical match of any untrained Apache warriors in combat and set out to prove it.

Third and last, General Miles got permission from his Washington superiors to stage a major field test of the heliograph communications system the U.S. Signal Corps had adapted from the equipment created by Sir Henry Manse for use by the British Army in India in the 1860s.

Miles had already experimented with heliographs when he commanded the District of the Yellowstone in 1878. Using Montana’s mountains, Miles’ command had established the first heliograph line in America between Forts Keogh and Custer. In 1884, Miles had tried it again, setting up a heliograph on Mt. Hood from which he’d communicated with Vancouver Barracks, 50 miles away. This new, rapid, fairly simple system of military communications impressed the general, and the clear sunlight between the mountain ranges of the great southwest provided him a perfect playing field upon which to experiment further.

Something needed to be done to improve military communications. The Apaches had already learned to cut the copper telegraph wires between forts sometimes hundreds of miles apart, and couriers galloping messages between units in the field were sitting ducks to be picked off by watchful Indians. Even when the telegraph wires were up, they weren’t always directly connected between all these distant forts. Gaps in the lines had to be filled by civilian telegraphers working for the railroads or stage lines. The problem with sending confidential military dispatches over commercial telegraph lines was that their civilian operators were prone to temptation. The latest military strategy or report of an Apache attack somewhere would often quickly be sold out the back door to a yellow journalist. The next day, local newspaper headlines would scream about the slaughter of some lonely ranchers, or argue with new tactics used by the Army’s troops. Town officials and residents of territorial mining burgs would often begin yelling about Apache outrages before the military men even had a chance to respond to them. As the new general on this bloody frontier, Miles was determined to regain the upper hand and keep his military messages confidential, away from prying civilian eyes.

The general’s 34 heliographs were shipped from Washington as fast as General William B. Hazen, the Army’s Chief Signal Officer, could round them up from forts around the country. He included 10 Bausch & Lomb telescopes and 30 marine binoculars with smoked lenses for picking up distant signals. Miles put 2nd Lt. Alvarado Fuller of the 2nd Cavalry in charge of the new network of 14 stations his engineers planned for Arizona, and Lieutenant Edward E. Dravo from the 6th Cavalry drew the same assignment for the 13 observation posts planned for New Mexico. While another class of heliograph operators was trained back at Signal Corps headquarters in Fort Myer, Va., the initial 11 of the Army’s first “field specialists” arrived at Fort Bowie. Lieutenant Fuller had his first station flashing messages by April 26, while the last, the 27th heliograph outpost, went on-line July 14.

Each heliograph station comprised five to 10 soldiers, including operators, guards, cooks, and couriers. The mountain-high outposts closed at dark, with the men at many of them moving down to lower, more sheltered campsites where it was warmer and water and supplies could be more easily received. Heliographs needed sunny weather to function. Messages were delayed by cloud cover and could be interrupted for days with the onset of the rainy season in the southwest in June. Men were rotated among the stations regularly to relieve the monotony of the duty.

The heliographs were transported up the mountains in three custom-leather cases. Some heliograph stations near the end of the line communicated with only one other station; others, near main forts like Bowie, talked to as many as five other stations. If the sun was in front of the operator, only one mirror was used. If behind him, a second mirror had to flash the setting sun onto the first 8-inch square mirror, which was adjusted and aimed along a sighting

rod. A metal shutter mechanism on a second wooden tripod intercepted this mirror’s reflection and by rapidly opening and closing this shutter by its handle, the heliograph operator transmitted short and long flashes corresponding to the dot and dash letters and numbers of the English alphabet in the famous Morse code. Messages averaged about 50 words each, transmitted at roughly 10 words a minute as the operators became more proficient.

And flash they could, since most of the stations were situated at least 4,900 feet up mountainsides, sited against dark backgrounds like timber or big rocks. The remarkable clarity of the desert air allowed Lieutenant Wittenmayer at the 14th installation on Mt. Reno, near Fort McDowell north of Phoenix, to flash a line-of-sight message to Captain Murray on Mt. Graham, a major transmitting station northwest of Bowie Peak above territorial headquarters at Fort Bowie, a distance of 125 miles. The captain then turned his instrument around and relayed the message another 95 miles to Lieutenant Hart at Fort Huachuca, the southernmost Army fort above the Mexican border. Those 215 miles with a single intervening station composed the two longest flashes in communications history and demonstrated the superiority of these newly modified American heliographs over the equipment used by the British and French armies at that time.

On May 2, Captain Henry W. Lawton arrived at Fort Bowie to command an expedition to chase Geronimo once more and either kill him or compel his surrender. Lawton’s soldiers were made up of 35 men of Troop B, 4th Cavalry; 25 men of Troop D, 8th Cavalry; several junior officers and a surgeon; plus 20 Indian scouts with the famous Tom Horn in charge. Two pack trains of 50 mules and 14 packers each carried this large patrol’s supplies as it set off toward the Sierra Madres as General Miles’ best hope. Lawton spent a frustrating month in Mexico, but returned to the States when he learned that the hostiles were again loose north of the border.

On June 5, the heliograph station at Antelope Springs, southwest of Tombstone, observed a party of Indians heading south. That information was flashed to Forts Bowie and Huachuca. Next morning by heliograph and courier, the sighting was relayed to Captain Lawton, who was camped near Calabasas on the Santa Cruz River south of Tucson and just north of the border. Lawton sent several detachments in hot pursuit and one of these, under Lieutenant Robert D. Walsh, surprised the raiders in the Patagonia Mountains due west, capturing their horses and equipment. The Indians fled on foot.

The Apaches learned quickly from their mistake. The June 5 communication was the only time an observation post spotted a war party and heliographed a strike force to charge in pursuit. Thereafter the Apaches remained south of the border until their final surrender in September 1886. Lawton crossed back into Mexico on June 11 and his men kept up their exhausting search until the end of August, when Lieutenant Gatewood and two Apache scouts (whom Miles had finally rehired) succeeded in tracking down Geronimo and his renegades for a preliminary parley.

Throughout that long summer of 1886, Lawton had to rely on his Indian scouts and the Mexican telegraph for information and reporting, for there were still no heliograph stations in Mexico. He had heliograph equipment with his pack train, but it was out of signaling range below the border. When Lawton reached Texas John Slaughter’s San Bernadino Ranch just across the Sonoran line on August 29, he sent a message via his heliograph to Miles that Geronimo and his band were coming north to surrender.

The heliographs had additional uses. Their operators reported daily weather conditions in their areas and passed along orders concerning troop movements. They used the heliographs to requisition supplies for themselves and the heliograph troops guarding the waterholes and ranches near the border. The observation posts also prevented troops from going out on useless scouting missions to investigate every spooked rancher’s report of large dust clouds on the horizon or strangers passing by on horseback.

Bruno J. Rolak, in his analysis of the use of the heliographs for the Journal of Arizona History, noted that because Apaches also carried field glasses and had seen heliographs occasionally used in Arizona since 1882 under General Crook, they certainly knew the purpose of the flashing mirrors. Lieutenant Fuller mentioned in his report that “from the time the heliograph was put into a particular section of the country it was noticed as a fact that the Indians were never ever again seen in that vicinity during the campaign.”

The extensive heliograph network thus established a protective barrier that the Indians knew they could not penetrate unseen during daylight, and the Apaches were always reluctant to travel at night. Miles’ efficient communications system, using heliographs, telegraph, and couriers, established a defensive perimeter around the southwest which, after the skirmish of June 6, the Apaches made no further efforts to penetrate. The renegades could no longer recruit more disgruntled Apaches from the San Carlos Reservation to the north or raid American ranches for weapons, ammunition, and horses. The line of flashing mirrors thus brought security to southwestern ranchers. Miles has never been given much credit by historians for this successful tactic.

Arguably, Nelson Miles established the most elaborate and effective communications network in the U.S. Army’s history up to that time, and superior to any army’s in the world at the end of the 19th century including the British, who pioneered the instrument. With the heliograph Miles linked a vast territory, 300 miles

wide by 200 miles long, over which a military message could be sent 400 miles on a zigzag route and a reply received within four hours. As a side note, Rolak mentions that this was also the first military campaign to use a telephone. A telephone line hooked Fort Huachuca to the New Mexico & Arizona Railroad depot seven miles north of the fort. Colonel William H. Royall, Commander of the 4th Cavalry there, stationed a soldier at the railroad depot to telephone the daily arrival of visitors, sick and wounded soldiers, replacements, and supplies.

The credibility and importance of military signal communications increased considerably as a result of this successful campaign, thanks to the usage of the heliograph, which reached its zenith during this deployment. After Geronimo and the Chiricahuas were trained off to prisons in Florida, Miles’ heliograph network was disbanded for a while. In 1890, his 2,000-mile heliograph network was re-established for two weeks to 51 stations across the territories for one final, major field exercise, after which they were all taken down for good.

Today, General Miles’ flashing mirrors are seldom remembered and only four of the original mirrors still exist on display at such places as the Museum of the U.S. Army Signal Corps at Fort Gordon, Ga., and the Fort Huachuca Historical Museum in southern Arizona. They had, however, some life yet to live. In 1898, heliographs saw limited service with occupation forces in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War, in which Miles was also prominently involved. In 1906 the Signal Corps augmented their telegraph communications with sun-flashing signals during the Moro insurrection in the southern Philippines. But as the frontier century sped into the 20th and more deadly, mechanized warfare reared its ugly head, the U.S. Army’s instruments of the sun were gradually replaced by a new, more rapid tool for military communications—the wireless radio.

Miles Swarthout is the screenwriter of The Shootist, John Wayne’s final film, as well as having edited a recent collection of his late father Glendon’s short stories, Easterns and Westerns, available from Michigan State University Press. His new Western novel from Forge Books, The Sergeant’s Lady, is set in a heliograph station on an Arizona mountaintop during the end of the Geronimo campaign in 1886. He can be reached at his family’s literary Web site, www.glendonswarthout.com.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments