By Blaine Taylor

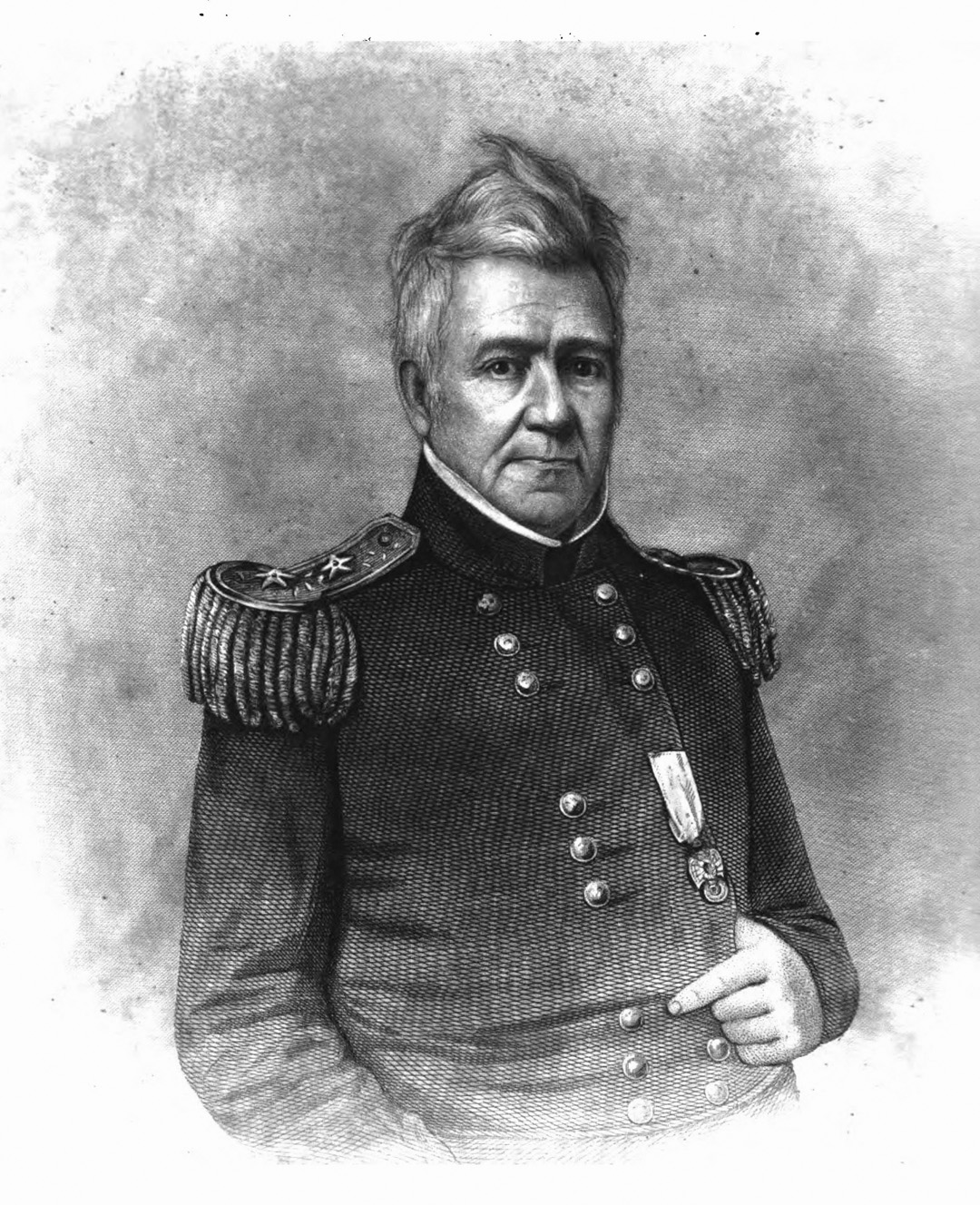

Few in the unincorporated community in Baltimore County that bears his name know of the deeds of the eminent American brevet Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Towson, even though his portrait hangs in the expanded Maryland Historical Society, a plaque honoring him is displayed outside the Baltimore County Courthouse, and a major Maryland university bears his name.

Even among War of 1812 buffs, who know the accomplishments of great generals such as Andrew Jackson and Winfield Scott, Towson’s name might be too obscure for them to cite his specific contributions to the American cause in that conflict, despite Towson having served under Scott in two of the war’s most important battles on the volatile U.S.-Canadian border.

Towson is remembered today not only as an astute battlefield commander, but also for having served for 35 years as paymaster general of the U.S. Army from 1819 until, while still in uniformed service he passed away in 1854.

One anecdote tells of how he was informed of being granted a commission in the U.S. Army while he was busily engaged laying a barn floor. The messenger who bore the tidings, along with the owner of the barn, went to the construction site to inform Towson of his commission, wondering all the while how he might receive the good news.

As Towson was driving a spike through a rough, unhewn wooden plank, the messenger announced in a loud voice, “Towson, I have your commission.” Shaking with pleasure at these glad tidings, Towson did not look up from his task until he had driven home the spike. Casting his hammer aside, he proudly said, “That is the last spike that Nathan Towson will drive until he sends one into the touchhole of the enemy’s cannon!” Unfortunately, there is no record of whether he got an opportunity to do that, but it leaves no doubt as to his patriotic fervor.

The community of Towsontowne (now Towson), Maryland, reportedly was founded when William and Thomas Towson of Pennsylvania began farming at what is now the junction of York and Joppa Roads in modern downtown Towson. With the construction of the Towson Hotel by William’s son Ezekiel, Towson became the market center for the transport of goods to Baltimore, and also for the sale of farm produce, which still occurs regularly at the local farmers’ market sponsored by the Towson Chamber of Commerce.

Towson was born on January 22, 1784, on his family’s farm as the 12th and last child of Ezekiel and Ruth Towson. Young Nathaniel’s parents had opened a tavern at what is now the Towson Roundabout at the intersection of York, Joppa, and Dulaney Valley Roads in Baltimore County.

Formerly Bosley’s Hotel, today it is Souris’ Saloon. Towsontowne, seven miles north of the port of Baltimore, was named in the family’s honor for having built the first home on a distinct ridge. Nathaniel grew up there and later went to farm in both Kentucky and Mississippi.

The future Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Towson began his successful military career during the War of 1812 and was considered afterward to be one of the most accomplished artillery officers in the United States. Before that, though, as a still roving 19-year-old, Towson moved to Natchez, Mississippi. He was living there in 1803 when United States bought approximately 530 million acres in a vast land deal with Napoleonic France known as the Louisiana Purchase, in which the French signed away their claim to the territory of Louisiana. Since many of the French inhabitants were unsettled at the prospect of belonging to the relatively new United States, local volunteer companies of militia troops were formed to enforce the American claim should any difficulties arise. Young Towson joined one of these militia companies and eventually rose to command the Natchez Volunteer Artillery. In that post, he earned a reputation for both roughness and gallantry. His superiors noted that he rarely shrank from undertaking tough tasks that they assigned to him.

Returning to Baltimore County in 1805 to become a farmer, two years later Towson joined the Maryland State Militia when the British Royal Navy attacked the Baltimore-built U.S. frigate Chesapeake in what became known as the notorious Chesapeake-Leopard Affair of 1807. This almost resulted in a renewed state of war between Great Britain and the still embryonic United States before passions cooled.

Five years later, in 1812, Towson was duly commissioned in the U.S. Regular Army as an officer. Soon renowned as one of its most useful officers, Towson was appointed a captain in the U.S. 2nd Regiment of Artillery in March of that year. Forming his company, Towson and his men sailed from Baltimore to Elkton, Maryland, then marched overland to Philadelphia, where they joined the 2nd Artillery Regiment, part of the command of General Winfield Scott. His force was then stationed on the shores of Lake Erie on the American-Canadian frontier at Buffalo, New York, for service in the War of 1812’s Niagara campaign.

Just north of the United States lay Great Britain’s colony of Canada, taken from the French in 1763. As was the case in the American Revolution, this locale again seemed the best and most logical place for the American Republic to attack its British foe. President James Madison declared war on England in June 1812, and had a force of 5,000 U.S. soldiers known as the Army of the Niagara, deployed on the U.S.-Canadian border.

“The acquisition of Canada this year as far as the neighborhood of Quebec will be a mere matter of marching!” said former U.S. President Thomas Jefferson upon the formal declaration of war. It was a foolish boast that fell flat.

As with the earlier failed American invasion of British Canada during the Revolutionary War, the attempts that occurred between 1812 and 1814 also proved to be doomed. The fighting soon bogged down in stalemate, and the conflict became known as “Mr. Madison’s War.” New England even opposed it outright, going so far as to consider secession from the union at the Hartford Convention.

Between seasonal campaigns, various local truces were sometimes declared so that the officers of both sides might socialize a bit. At one of these soirees, a British officer was reportedly heard to insult one of the ladies present. As the story goes, Captain Towson promptly knocked the offender down. In the resulting duel with pistols, Towson lost a finger while his British opponent suffered a more serious injury, but both lived.

Towson would soon be involved in far greater battles. In all, Towson saw action in the Battles of Fort George, Stoney Creek, Queenston Heights, Chippewa, and Lundy’s Lane, although he is best known today for the last two engagements.

During the active military campaign seasons, various Maryland citizens took part, and one of these was U.S. Navy Lieutenant Jesse Duncan Elliott, who with 50 men surprised and captured two British ships on Lake Erie. Elliott was to become a useful ally to his fellow Marylander, Towson.

Elliott was born in Maryland in 1785, and enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1806, being promoted to officer’s rank in 1810. After the gallant exploit near Buffalo, Elliott was posted to Sackett’s Harbor and in July 1813 was named master commandant in command of 30 lieutenants, also commanding the 20-gun brig USS Niagara, itself built on Lake Erie.

Elliott also served as Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s second in command at the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, for which Congress voted him a gold medal. That November, he was awarded command of the new sloop-of-war USS Ontario, just then completed at the port of Baltimore, seeing action with the U.S. Navy’s Mediterranean Squadron in 1815. Promoted to captain, Elliott received other sea commands and was officer in charge of the U.S. Navy shipyards at Boston and Philadelphia.

Elliott and Towson typified the high caliber of officers produced by Maryland during the War of 1812. In all the Canadian fighting in which it was involved, Towson’s company became renowned as being the first into combat and the last to leave it. Indeed, on one occasion when defending Fort Erie against the British-Canadian forces, his men reportedly fired their cannons so rapidly and continuously that the fortress the enemy nicknamed “Towson’s Lighthouse” because of the seamless flame from its guns.

In one of their joint adventures, Towson helped Elliott capture the British ship HMS Caledonia off Fort Erie in October 1812. For his bravery Towson was brevetted a major, his first field officer grade. Elliott was ordered to construct, borrow, or take shipping to gain control of Lake Erie. While he was busy supervising such shipbuilding near Buffalo, HMS Caledonia and Detroit, both of which were armed British Royal Navy brigs, cruised by on a reconnaissance mission, anchoring just under the American Fort Erie, near the lake’s neck.

Elliott’s plan was for a night seizure by stealth, with Towson’s soldiers armed with pistols, swords, and sabers. Commanded by Elliott on water, the expedition set sail in two boats using muffled oars. One boat with Towson sailed ahead but was sighted by HMS Detroit and duly fired upon. When the Navy master wanted to abort the discovered amphibious assault, Towson overruled him, took over, and slid alongside HMS Caledonia.

All but one of their grappling hooks missed their mark, again exposing the Americans to deadly enemy fire. Nevertheless, even in the dark, Towson got his men aboard the British vessel, and in less than two minutes the fighting ceased with the surrender of her crew and the Caledonia in Yankee hands.

Meanwhile, its crew being so transfixed by the fighting aboard the Caledonia, the Detroit was boarded with but little notice by Elliott and his men and also captured in just 10 minutes of combat. The topsails of both vessels were sheeted, and they were soon underway, bound for American captivity.

Towson was wounded during his successful repelling of a British attack at Fort George in Upper Canada in July 1813. Scott’s forces crossed the Niagara into Canada on July 3, 1814, where they faced British Maj. Gen. Phineas Riall. Towson’s second brevetted promotion was to lieutenant colonel for achieving even greater glory at the Battle of Chippewa in Upper Canada on July 5, 1814. His superiors wrote that he had garnered this new laurel by “greatly distinguishing himself” against the British.

Indeed, his guns there were said to have stood firm in defeating a charge made by British grenadiers, smashing their lines with artillery barrages using heavy iron balls that compelled the redcoats into headlong retreat. However, the Battle of Chippewa cost the Americans dearly.

The clash reduced American effective troops to 2,644 men as opposed to a British-Canadian force of 2,995, with reinforcements of 1,230 more redcoats six miles off. This set the stage for the followup Battle of Lundy’s Lane three weeks later. The battle opened at 5 pm on July 25, 1814, and lasted until well after midnight. It became one of the war’s bloodiest battles.

As part of an advance force of 1,200 men, Towson and his 70 artillery gunners crossed a bridge over the Chippewa River with Scott’s First Brigade. Earlier at Chippewa, Scott had been surprised to find the British army on the bank opposite him. Rather than cause a panic among his own men by withdrawing, Scott had stormed ahead, attempting to make the British believe he was coming with the entire American army. Riall later famously acknowledged that Scott’s men were not despised Yankee militiamen: “Those are Regulars, by God!”

As it evolved, the Chippewa-Lundy’s Lane campaign became known in both American and Canadian history not so much for the battles, but for the gray militia-colored uniforms that Scott’s men were forced to wear in lieu of American Regular Army blue. The Corps of Cadets of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, eventually adopted gray as its official uniform color to honor Scott’s troops, a uniform tradition that endures to this day.

Meanwhile, the main body of the British army was still rapidly advancing from the Canadian town of Queenston, with a column head having reached Lundy’s Lane. This was a road running a short way due west of the river below Chippewa, near the roar of the famous Niagara Falls. Scott’s army now faced an enemy numbering 1,600 to 1,800 men.

By dusk, however, both sides had received reinforcements, with the Americans fielding 2,100 soldiers and the British about 3,000. Fighting far into the night, the sound of the guns was nearly drowned out by that of the steep falls in the background. The American army withdrew with 171 dead, 572 wounded, and 110 missing or captured. As for the British, they suffered 84 killed, 599 wounded, 193 missing, and 42 captured. The battle was considered a draw. When Towson’s guns had fired their final rounds, 27 of his 36 gunners were either dead or wounded.

Some contemporaries regarded the Battle of Lundy’s Lane as a tactical British victory, with Riall alleging that not only had the Americans given up their camp but also abandoned most of their equipment, baggage, and even supplies in the nearby river. In addition, the British asserted that they were the ones who retained control of the battlefield. The U.S. army fell back on Fort Erie “in great disorder,” the British charged. Despite this, it was noted by the Americans that the Canadian site of Street Mills had been burned and the Chippewa Bridge destroyed.

Thus, both sides claimed victory, with Towson duly lauded in after action reports as being “competent” in the handling of his battery’s pair of 6-pounder guns and a sole 5½-shell howitzer that had battled British gunners and infantry at both Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane.

One entire Towson gun crew had been killed during an exchange of deadly fire, while he and his men were credited with having added captured British cannons to their battery.

Oddly, Scott allegedly never filed an official report on the disputed Battle of Lundy’s Lane, and this was used against him during his unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. presidency in 1852, when a pamphlet was published charging that Towson’s force “stood and were shot down, and fired to animate the infantry to stand and be shot down.” But Scott would go on to become the first commander of the Union Army when the American Civil War began in 1861. Despite the later charges, Scott was, and is still is, acknowledged as one of the heroes of the War of 1812.

Having been promoted to brigadier general, one of Towson’s last official acts was to preside over an 1848 court of inquiry on Scott. The investigation sought to determine whether Scott had misappropriated public monies to bribe Mexican Army generals during the U.S.-Mexican War that ended that year. The charges were dropped. For his noted discretion during the hearings, Towson was brevetted yet again, this time to major general.

Elliott also got into career difficulties following the War of 1812. Charged with official misconduct during one of his Mediterranean commands, Elliott was court-martialed in 1840, receiving a sentence of four years’ suspension from the naval service. By then, Commodore Elliott also became embroiled in a postwar dispute over his conduct at the Battle of Lake Erie that ended only with his death on December 18, 1845. Controversy had also flared around him when he placed an image of President Andrew Jackson as a figurehead on the U.S. Navy frigate Constitution, which was seen as a blatant political act.

Towson sidestepped any and all such controversies. Indeed, in his long-running posting as U.S. Army Paymaster General, Towson disbursed $70 million “without any hint of impropriety,” it was noted at his death on July 20, 1854, at age 70 in Washington, D.C.

Towson’s noteworthy record on the Canadian frontier during the War of 1812 brought him very few laurels, but one celebration did recognize his deeds. The January 9, 1815, edition of the American Commercial and Daily Advertiser covered a celebration titled, “A Tribute to Valor.” The celebration honored a pair of Free State heroes of the War of 1812, George E. Mitchell of the 3rd Maryland Militia and the Regular Army’s Nathaniel Towson.

Present also were other famous contemporary warriors, including American commander at the September 12, 1814, Battle of North Point Militia Brig. Gen. John Stricker, and Baltimore’s Fort McHenry Regular Army post commanding officer Lt. Col. George Armistead. Toasts were made all round, including this one to Towson: “In 1812—under the batteries of Erie—he displayed the bold enterprise and undaunted valor of an American. The fire of his artillery has, since—in many a well-fought field—awed the enemy until its correct aim and incessant blaze has gained the distinction of ‘Towson’s Lighthouse.’” The paper added that this toast was followed by nine cheers.

The object of these hurrahs lies today on a pleasant lawn slope at Oak Hill Cemetery in the Georgetown section of Washington, D.C., at his wife’s side. Above them was placed a beautiful white marble monument bearing the following inscription: “Nathan Towson, Brevet Major General and Paymaster General, United States Army. Sophia Towson, wife of Nathan Towson.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments