By Kelly Bell

Rifle flashes erupted at intervals on the base of the slope. The flashes gave away the location of the confederate troops advancing in large numbers in the darkness of the night of July 2, 1863, on the eastern side of Culp’s Hill southeast of the town of Gettysburg. The 4,000 Rebels in three brigades belonged to Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division of soldiers hailing from the Old Dominion.

Waiting for their attack on the eastern slopes of the key position on the extreme right of the Union Army of the Potomac was a solitary brigade that belonged to Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s XII Corps led by one of the oldest officers in the army. The Union Army commander, Maj. Gen. George Meade, had stripped the hill of most of its troops to reinforce other parts of his line, and the 1,300 rifles of Brig. Gen. George Greene’s 3rd Brigade of Maj. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ First Division braced themselves for the daring night attack.

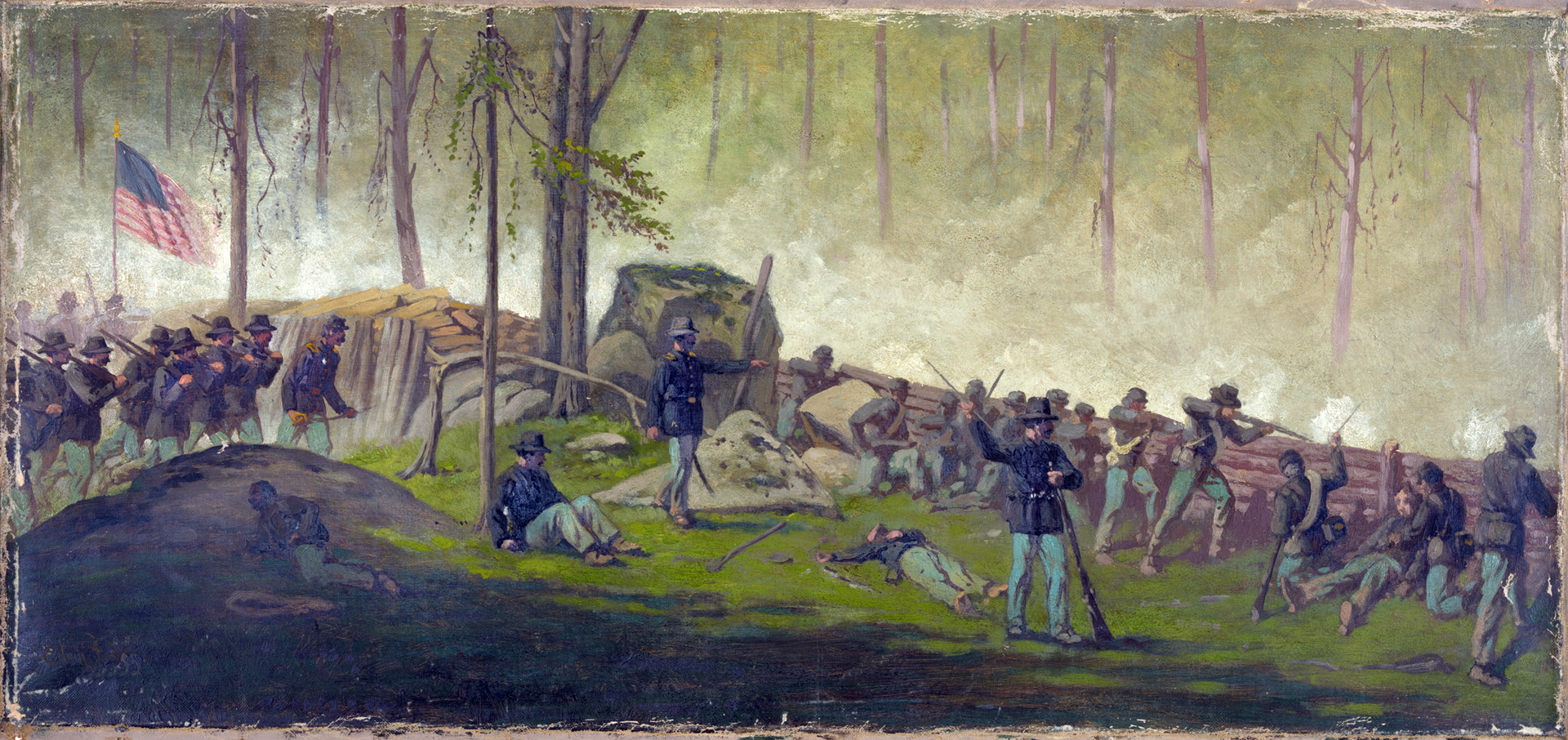

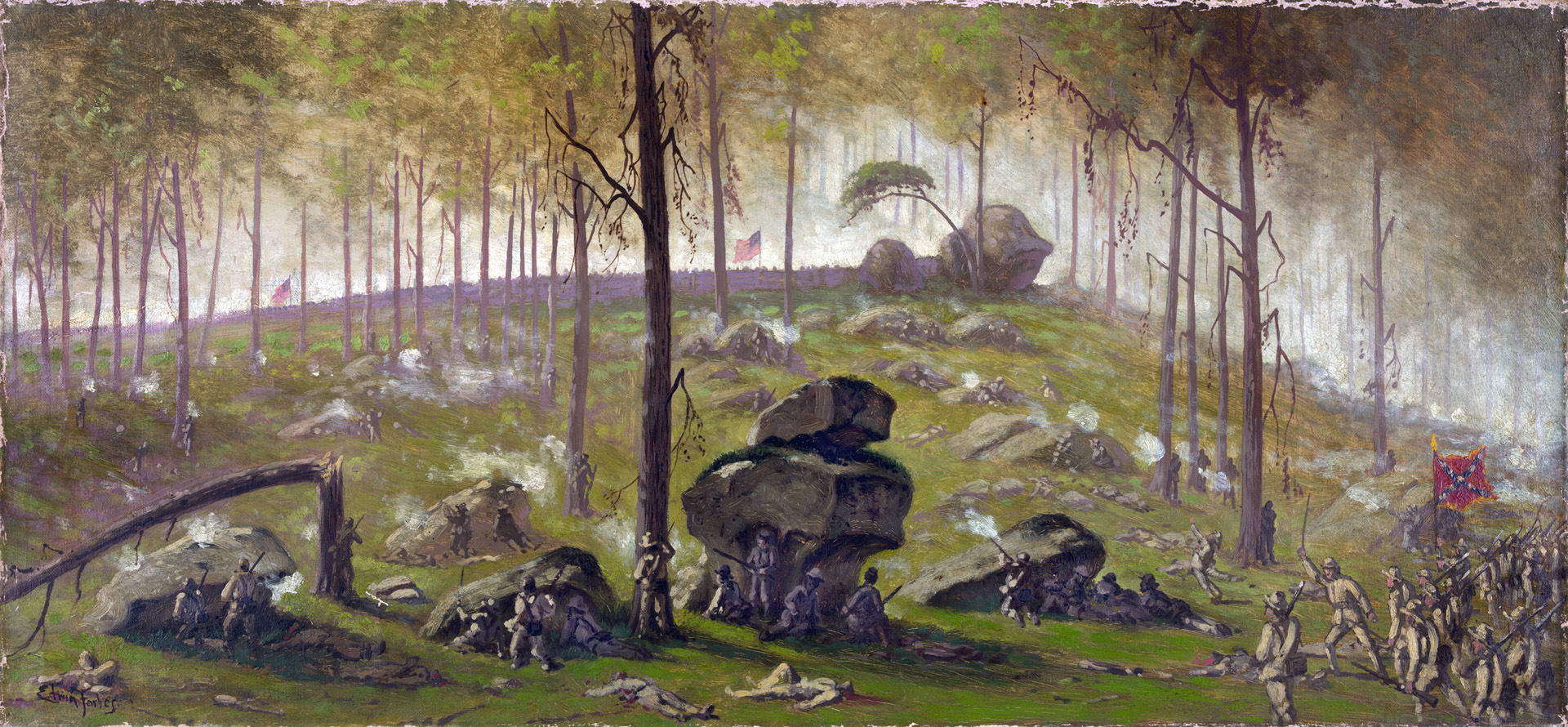

The Union troops had evened the odds against the superior attacking force by erecting strong breastworks of logs that integrated the large boulders and ledges that dotted the slopes of the hill. Most of the troops would be able to fire through slits in the barricades at the advancing Rebels, which would greatly reduce the likelihood that they would be killed or maimed by the low-velocity bullets and balls aimed at them.

Nevertheless, the weight of the Confederate attack was enough to rattle the nerves of the most seasoned veterans in the blue ranks. Many of the Yankees knew that they were entrusted with holding a crucial part of the Union line. If the Confederates could drive them from their fortified positions, the Rebels could seize control of a portion of the Baltimore Pike, Meade’s lifeline to his supply base 20 miles away at Westminster, Maryland. If that occurred, the entire Union army would be forced to fall back south, possibly uncovering Baltimore and putting Lee’s army that much closer to the nation’s capital. Aware of their solemn duty, Greene’s bluecoats put their minds to the task. They steeled their nerves for a firefight in which they were principal actors that came at the close of the second day of a titanic clash on Northern soil midway through the conflict.

The name Gettysburg is seared into the American consciousness as the bloodiest three days in the great republic’s history. The battle ended the Confederacy’s dream of a separate nation after two years of back-and-forth jousting turned irreversibly against the secession states. Even after all the millions of words that have been written about this battle during ensuing decades there are still aspects of the Gettysburg decision that remain obscure. The struggle for a nondescript promontory called Culp’s Hill ranks, for strategic significance, right up there with such legendary chapters as Little Round Top and Pickett’s Charge. Being overlooked takes nothing away from the significance of this aspect of the battle.

In the wake of the Union Army’s disaster at Chancellorsville under the command of Maj. Gen. “Fighting Joe” Hooker, a campaign that unfolded during the first week of May 1863, the U.S. government replaced Hooker on June 28 with Maj. Gen. George Meade. President Abraham Lincoln and his top military advisers selected Meade, who most recently had led the V Corps at Chancellorsville, because Meade did not scare easily and was able to keep a clear head on the battlefield under pressure. The acerbic Meade lacked the charisma of Maj. Gen. George McClellan, one of the early commanders of the Army of the Potomac, or Hooker, and his appointment to replace Fighting Joe surprised many in the army.

General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had won a decisive victory over Hooker at the crossroads of Chancellorsville a short distance west of Fredricksburg, Virginia, but the success was tainted by the loss of Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Stonewall died of complications from a friendly fire wound received while following up his May 2 flank attack on the Union XI Corps, which won the battle for the South. In the aftermath of the battle, Lee reorganized his army into three corps, with the newly created Confederate II and III Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard “Old Bald Head” Ewell and Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, respectively. General James Longstreet commanded the Confederate I Corps.

Lee decided to follow up the victory at Chancellorsville by invading the North a second time to seize food from the fertile farmlands of Pennsylvania and relieve the pressure on the battle-scarred landscape of northern Virginia. Lee’s forces began shifting to the Shenandoah Valley the first week of June in preparation for the invasion. Using the Blue Ridge Mountains as a screen, the infantry marched north unopposed. To ensure the Union army was confused as to the exact location of the Confederates, Lee entrusted Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart with using his superb cavalry to keep Union forces on the east side of the mountains from being able to capture the mountain gaps.

Stuart did that job well, and the 70,000-strong Confederate Army of Northern Virginia finished crossing the Potomac River on or about June 24. Ewell’s corps, which formed the vanguard of the Confederate army, fanned out and marched all the way to Carlisle and York, Pennsylvania, by the time Meade took command of the pursuing Army of the Potomac.

Having no notion of the exact whereabouts of Lee’s forces, Meade sent Brig. Gen. John Buford’s First Division of the Union Cavalry Corps into Pennsylvania to locate Lee’s army. Following Buford were three corps forming the vanguard of the Army of the Potomac led by Union I Corps commander Maj. Gen. John Reynolds. On June 30, Buford ran headlong into the middle of the Confederate army moving east when he encountered infantry of Hill’s corps on the Chambersburg Pike west of Gettysburg. Buford fired off a dispatch to Reynolds indicating that he had found the main body of Lee’s army, and Reynolds immediately ordered his three corps to march to Gettysburg.

The following day, Buford consolidated his command, which was spread out looking for Lee’s army, on the ridges west of Gettysburg. Buford planned to have his men, who were armed with various makes of single-shot, breech-loading carbines, fight dismounted. This would force the Confederate infantry commanders to deploy their men from column into line of battle, slowing their advance and revealing their strength.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division of Hill’s corps ran into Buford’s dismounted troopers about 7:30 am on July 1. Reynolds had arrived at Gettysburg ahead of his troops that morning, and he and Buford conferred at the Lutheran Seminary near Chambersburg Pike on the west side of Gettysburg. The lead elements of Reynolds’ I Corps soon arrived, and the general deployed them on McPherson’s Ridge and allowed Buford’s cavalry to fall back to new positions around the town in anticipation of the arrival of other Confederate units. By noon, Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ division of Ewell’s corps had arrived and occupied Oak Hill northwest of the town, which endangered the right flank of the Union I Corps. By that time, Reynolds had been killed by a Confederate sharpshooter, and the command of his corps had passed to Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday, the I Corps’ senior division commander.

Federal reinforcements arrived in the nick of time. Having made a forced march to Gettysburg, Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard deployed the bulk of his XI Corps north of Gettysburg to meet Rodes’ attack. The arrival of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division of Ewell’s corps via roads leading into the town from the northeast put it astride Howard’s right flank. The unlucky Howard, whose corps had been smashed by Jackson, was once again whipped by the Confederates under Early. Early’s division proceeded to roll up Howard’s line. Howard’s men fled south through the streets of Gettysburg toward the safety of Cemetery Hill. With Howard’s corps routed, Doubleday’s infantry soon found Confederate infantry attacking them from the rear, and they also retreated toward Cemetery Hill. Ewell’s third division, under Johnson, soon arrived and deployed on Early’s left flank.

Lee arrived on the battlefield while the Union retreat was in progress. To partially offset that command advantage, the Union forces benefitted from the arrival of Union II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. When Meade learned of Reynolds’ death, he had sent Hancock to take command of the army until he was able to arrive in person at Gettysburg. Hancock immediately began deploying the disorganized Union infantry to receive a Confederate followup attack.

As he went about establishing a strong position at Cemetery Hill, Hancock became anxious over the vulnerability of the right flank. Seeing several limbered batteries belonging to Reynolds retreating from Seminary Ridge toward Cemetery Hill, Hancock shouted for the captain of one of them to come over to him.

The officer Hancock summoned was Captain Greenleaf Stevens, commander of the 5th Maine Battery, I Corps. Hancock, pointing to Culp’s Hill, ordered Stevens to deploy his battery of Napoleon 12-pounder cannons on the hill to prevent the enemy from occupying it. Stevens, who believed the thickly wooded summit of Culp’s Hill prevented him from unlimbering atop it, decided instead to deploy on a knoll on the west end of the Culp’s Hill ridgeline. Stevens’ battery was soon shelling the Confederates. The knoll that Stevens chose for his position became known thereafter as Stevens’ Knoll.

Unfortunately for Stevens, he had no infantry support to prevent enemy sharpshooters from picking off his artillerymen one at a time. Hancock, who soon noted the weakness, at 5 pm ordered Colonel William Robinson, commanding the retreating 1st Brigade (known as the Iron Brigade) of Brig. Gen. James Wadsworth’s 1st Division of the I Corps, to march his troops to Culp’s Hill, which lay about a half mile southeast of Cemetery Hill.

Cemetery Hill was indeed a formidable position. Rising 100 feet above the terrain over which the Confederates would have to attack, the local burial ground’s most visible landmark was its arched brick gatehouse. The northwestern side of the hill was laced with walls and fences that would serve as ready-made breastworks for infantry. Its smooth, unforested top offered an excellent location for artillery.

Just south of Cemetery Hill lay Cemetery Ridge, and east of Cemetery Hill was Culp’s Hill. Along with Big Round Top and Little Round Top, which lay south beyond Cemetery Ridge, the high ground south of Gettysburg would serve over the next two days of battle as the Union army’s “fishhook” defensive line. The fishhook began at Big Round Top and ran north toward Cemetery Ridge until it curved at Cemetery Hill. Culp’s Hill formed the barb of the fishhook, anchoring the extreme right of the Union positions at Gettysburg.

Culp’s Hill was named after farmer Henry Culp, who owned the property in 1863 and who would lose a nephew fighting for the Union in the battle. With its heavily wooded and easily defensible slopes, Culp’s Hill was the perfect anchor for the far right of the Union line. Rock Creek flows past Culp’s Hill on its east side, and the Baltimore Pike skirts the hill to the southwest.

The rise is actually two hills. The higher, upper hill rises sharply about 180 feet above Rock Creek. About 400 hundred yards south, the lower hill rises 80 feet over the same watercourse. The lower hill slopes south to a swale called Spangler’s Meadow, which contains Spangler’s Spring. A saddle-shaped ridge connects the two elevations.

Hancock also ordered Colonel Ira Grover’s 7th Indiana Infantry, 2nd Division, I Corps to join the Iron Brigade on Culp’s Hill. Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes’ 6th Wisconsin Infantry unloaded entrenching tools from its supply wagon and began entrenching on the upper hill in anticipation of an imminent Rebel attack. Because of the shallow earth, the soldiers were not able to dig deep trenches. Instead, they felled trees and appropriated cordwood stacked by farmers.

Like all of the large hills at Gettysburg, the crest and slopes contained boulders of many shapes and sizes, and the soldiers incorporated them into their construction when possible. To finish off these breastworks, they capped them with head logs. When finished, the soldiers were almost completely protected because they were able to fire at the enemy from a slit between the head log and the part of the breastwork beneath it. This form of entrenching would continue throughout the battle as fresh units were rotated onto Culp’s Hill and the line extended the length of the upper and lower hills. No sooner had the Union troops entrenched than Confederate skirmishers began slowly working their way up the western slope of the upper hill.

Johnson had arrayed the bulk of his division on the west bank of Rock Creek. He was under the misconception that the upper hill was unoccupied. After nightfall his scouts blundered into the 7th Indiana, precipitating a flurry of rifle fire in the darkness. The Rebels scurried back downhill to report the Yankee presence to a surprised Johnson.

Just before dusk, Ewell had meticulously studied through a telescope the terrain of Cemetery Hill and the position of the Union troops atop it and decided the position was too strong to be overcome by direct assault. He did, however, realize that by taking Culp’s Hill his troops could outflank the Union forces on Cemetery Hill. The problem was that Lee had ordered him to move his command to the opposite end of the Confederate line to guard against Federal thrusts at that sector of the battlefield.

Ewell rode to Lee’s bivouac and convinced his superior to allow his corps to remain on the left and secure Culp’s Hill. Just after midnight Ewell sent a runner to Johnson with orders to “take possession of the hill if you have not done so already.” Johnson had formed a line of battle after dark and sent a reconnaissance party up the taller peak to see if it was unoccupied or lightly held, but it had reported that the Federals were there in force.

Johnson was overestimating the number of Union occupiers and reported inflated figures to Ewell, asking for further orders. The Yankees were being slowly but steadily reinforced, but when Johnson received his first response, they were still too few to have withstood a major assault by Johnson’s four brigades. By the time he received confirmation from Ewell late the next morning, the Yankees had absorbed sufficient reinforcements and had thrown up adequate breastworks to withstand the planned assault. The Confederates had wasted a promising opportunity to breach Meade’s defensive line.

Lee’s final orders to Ewell for July 2 were for Old Bald Head to make a demonstration against Union forces in front of him, and if that demonstration was promising to develop it into a full-scale attack. The position at Culp’s Hill was just as important to the survival of the Union army as the two round tops on the opposite end of the battlefield. If Ewell’s corps could capture Culp’s Hill, the Confederates would be able to seize control of the Baltimore Pike on the opposite side. The Baltimore Pike was the best road between Gettysburg and the nearest Union railhead at Westminster, Maryland. Cutting the Baltimore Pike south of Cemetery Hill would likely force Meade to withdraw from the battlefield over roads of poorer quality and seek a new defensive position much farther south.

After a tense night, substantial Union reinforcements arrived at Culp’s Hill. Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ 1st Division and Brig. Gen. John Geary’s 2nd Division of the XII Corps marched up Culp’s Hill at 6 am on July 2. The additional troops allowed the Union army to extend its line from the upper hill to the lower hill.

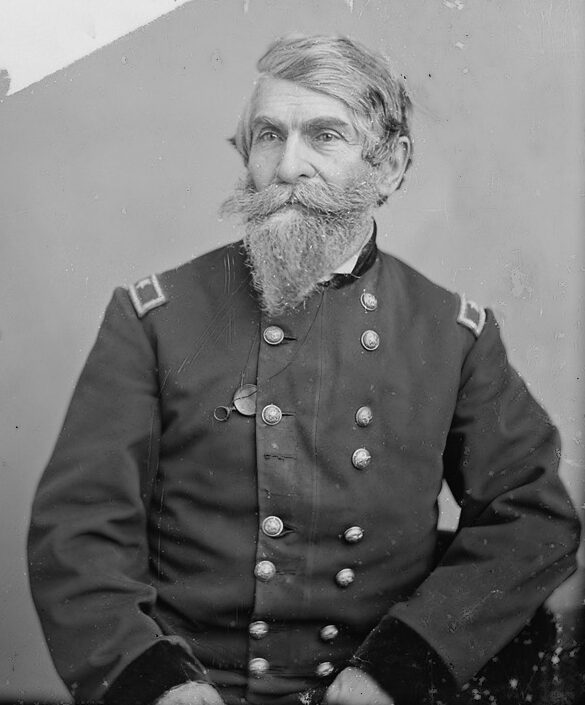

The Union army was fortunate to have Brig. Gen. George Greene, a civil engineer with extensive experience, leading one of the brigades atop Culp’s Hill. He ordered his men to entrench facing east adjacent to Wadsworth’s brigade. The 62-year-old Rhode Island native, who had overseen many large construction projects as a civil engineer, had rejoined the army in January 1862 as a colonel of the 60th New York Infantry and subsequently fought at Cedar Mountain, Antietam, and Chancellorsville. Greene personally inspected the construction of the fieldworks to ensure that they were well made and that the troops occupying them could withstand an assault by superior forces.

“Our position and the front were covered with a heavy growth of timber, free from undergrowth, with large ledges of rock projecting above the surface,” Greene wrote of his brigade’s position on the upper hill. “These rocks and trees offered good cover for marksmen. The surface was very steep on our left, diminishing to a gentle slope on our right. By noon on July 2 the full length of Culp’s Hill was strongly manned and fortified in anticipation of the pending Confederate assault.”

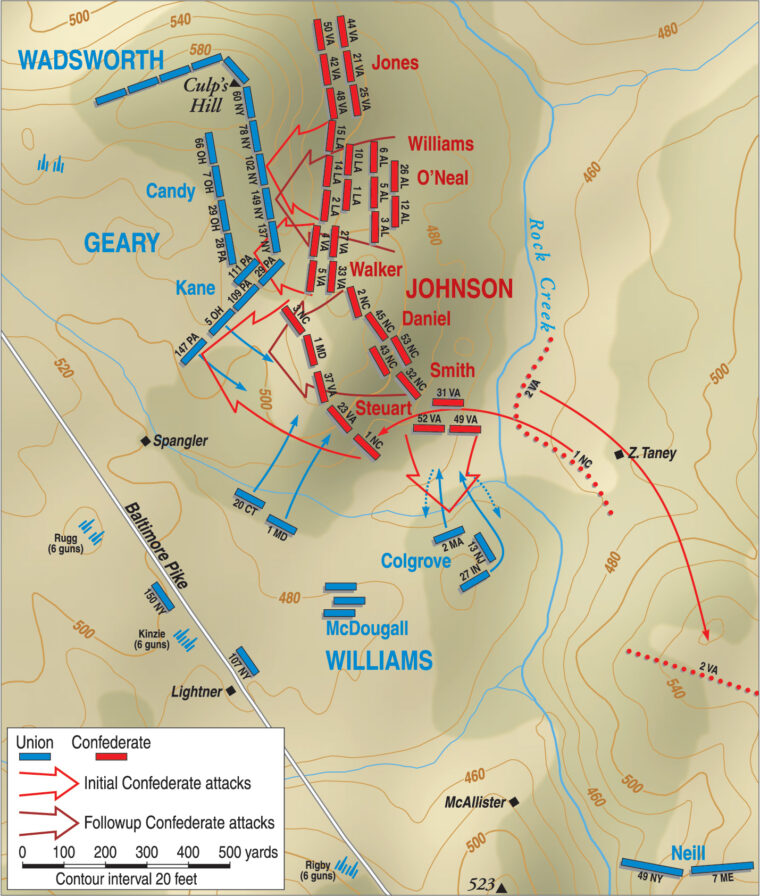

By midday on July 2, the frontline Union defensive positions at Culp’s Hill were held by Wadsworth’s division of the I Corps on the left of the upper hill facing north, Greene’s brigade of the XII Corps facing east, and Brig. Gen. Thomas Kane’s brigade of the XII Corps on the lower hill also facing east. Dug in behind these primary positions was a second line comprising the XII Corps brigades of Colonel Charles Candy, Colonel Archibald McDougall, Colonel Silas Colgrove, and Brig. Gen. Henry Lockwood extending from Spangler’s Spring through a copse called McAllister’s Woods. Lee ordered attacks that morning on both ends of the Yankee line.

It took Ewell until 4 pm to get his troops deployed to support Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps assault on the Union left. Ewell used the sound of Longstreet’s attack to the south as a signal, but instead of sending an infantry charge he limited his demonstration to shelling the Union lines, believing this would suffice to dissuade the Federals from opposing Longstreet.

The demonstration was carried out by Major Joseph Latimer commanding Andrews’ artillery battalion of Johnson’s division. The battalion comprised four batteries stationed on Benner’s Hill, which fired on Union forces on Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill. As many as 40 Yankee guns on Cemetery Hill soon found the range of the Rebel artillery atop Benner’s Hill and shelled it to devastating effect. As his guns were being withdrawn, Latimer was struck and killed by shrapnel. The withdrawal of the Confederate guns deprived Johnson’s infantry of artillery support for the remainder of the day.

Ewell’s guns atop Benner’s Hill did an acceptable job of hammering their target, but this did not convince Meade to sit tight and wait out the barrage. Meade sent the XII Corps south to face Longstreet, which left only Greene’s brigade atop Culp’s Hill.

Greene extended his line to his right to cover as much of the lower hill as possible, but his small force would be stretched dangerously thin should they be hit by a determined Confederate attack. Greene had kept most of his troops on his left, which meant that those on the right had so much of the breastworks to occupy that they were stationed a foot apart from each other, thus presenting a dangerously thin line against an enemy advancing in multiple ranks. The Confederates, however, were throwing the bulk of their available forces against the Union left and center, not realizing how weakly the right was held.

As darkness gathered at 7 pm, the Rebel pressure on the Union left and center was running out of steam. Realizing this, Ewell belatedly commenced his main infantry assault. Three brigades of Johnson’s division prepared to ford Rock Creek and assault the eastern slope of Culp’s Hill. The Confederate brigades right to left were led by Brig. Gen. John Jones, Brig. Gen. Francis Nicholls (under the command of Colonel Jesse Williams, replacing Nicholls who had been seriously wounded at Chancellorsville), and Brig. Gen. George “Maryland” Steuart.

Johnson’s fourth brigade—Brig. Gen. James Walker’s “Stonewall” Brigade—was to follow the other three brigades. But Walker was preoccupied with Union forces stationed east of Culp’s Hill and was late to join the attack.

There was still sufficient daylight for Greene to see the magnitude of the attack bearing down on him, and he hurriedly summoned reinforcements from Wadsworth and Howard, whose troops were tightly packed on Cemetery Hill in anticipation of an attack on their front by Early’s division. Wadsworth sent three regiments, and Howard sent four regiments. The Union reinforcements came bearing additional ammunition.

Jones had detached one of his six regiments, the 50th Virginia Infantry, to guard Confederate artillery posted on Benner’s Hill. The remaining five regiments had to attack up the steepest, heavily forested taller peak of Culp’s Hill.

Johnson’s three brigades splashed through the shallow waters of Rock Creek and pressed on toward the east slope of Culp’s Hill. As the fight developed, Jones struck Greene’s left, Williams hit Greene’s center, and Steuart attacked Greene’s right. As Jones’ regiments marched toward Culp’s Hill, artillery shells fired by Capt. R.B. Ricketts’ 1st Pennsylvania Artillery crashed into their ranks, but the veteran graybacks pressed on despite the whistling of shells overhead.

The main battle line of Jones’ brigade sent Greene’s skirmishers fleeing up the slope toward the safety of the breastworks. Most of the skirmishers made it, but some cried out in agony when struck by Rebel bullets that filled the air, striking the rocks and trees with audible thuds. Awed Yankees watched as Jones’ graybacks arrived on the slopes in force, skillfully loading and firing as they advanced on the breastworks of the upper hill.

Colonel Abel Godard’s 60th New York Infantry easily withstood Jones’ repeated charges. Godard’s men inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. One of those casualties was Jones. Seriously wounded, he was carried to a dressing station, leaving his men leaderless. Greene’s engineering expertise was a godsend for the Union. “Without breastworks our line would have been swept away in an instant by the hailstorm of bullets and the flood of men,” wrote Captain Jesse Jones of the 60th New York.

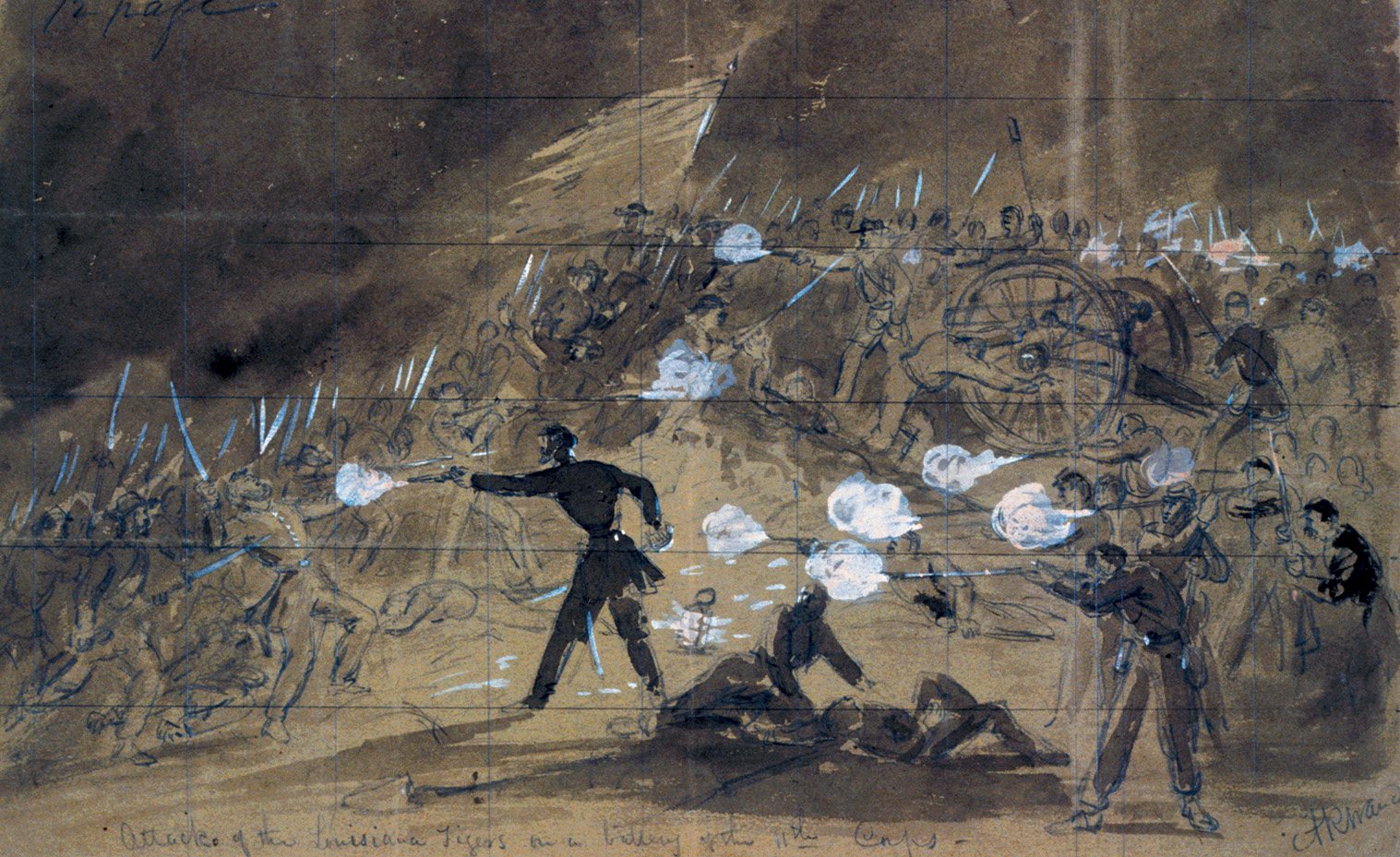

By this point it was completely dark, but this did the Confederates little good. Williams, who was leading Nicholls’ brigade comprising five Louisiana regiments, spent four hours trying to breach the fortifications facing it. In the darkness relatively few men on either side were hit despite the hail of bullets, but the Rebels could not get past Union breastworks manned by the 78th and 102nd New York Infantry Regiments. When their ammunition was exhausted, the Rebels fell back.

Steuart had his troops on the left occupy the empty breastworks on the lower hill and commence a cautious advance through the darkness toward Greene’s right flank. When Steuart’s men fired on some stray bluecoats they mistook as the main Union body of troops, they betrayed their position to Greene’s main force. The Yankees fired a withering barrage into Steuart’s densely packed ranks.

Two of Steuart’s regiments, the 10th and 23rd Virginia Infantry, managed to outflank the 137th New York Infantry led by Colonel David Ireland. Under extreme pressure, the Empire State troops dropped back to a secondary, southward-facing trench and managed to hold off Steuart’s charge. Still, Ireland lost a third of his men in the nocturnal firefight. This spirited defense and the darkness kept Steuart from realizing that the Confederate main objective, the Baltimore Pike, was situated only about 600 yards in front of him. Had the Rebels launched a determined frontal assault in that direction a huge disaster would have befallen the Union forces, but Steuart, unaware of the proximity and vulnerability of this vital target, never advanced in that direction. This pivotal attack would almost certainly have succeeded during daylight, especially considering the close, reinforcing proximity of the 1st Maryland (Confederate) Battalion.

In the confused nighttime encounter, the 1st North Carolina Brigade mistakenly fired on and pinned down the Marylanders. Also, at this point Hancock, who was on Cemetery Ridge and had become alarmed by the sound of a significant clash atop Culp’s Hill, sent the 1st Pennsylvania Infantry to reinforce the 137th New York. Nevertheless, the situation was far from secure for the bluecoats on Culp’s Hill.

By withdrawing a large number of troops from Culp’s Hill, Meade had committed a major blunder that almost cost the Union the war. Taking into consideration the mounting pressure Longstreet’s assault was putting on the Union left and that there was little activity around Culp’s Hill, Meade repositioned the XII Corps from Culp’s Hill to reinforce the left. Two of the XII Corps’ brigades marched off Culp’s Hill, headed down the Baltimore Pike, got lost, and reached Rock Creek at dusk. In that location, they set up a bivouac to await further orders.

Had the XII Corps’ final unit on Culp’s Hill, Greene’s 3rd Brigade, also departed its positions, Lee’s army likely would have won the battle. However, as the brigade was preparing to move out a messenger arrived with news that Confederate troops were advancing in force on Rock Creek and Culp’s Hill. Greene ordered his men back into position behind their breastworks and had couriers locate and recall some of the already departed troops. This still left him with too few soldiers to man the lines stretching along the ridge connecting the two sections of Culp’s Hill and those extending down to Spangler’s Spring. For the moment these breastworks remained empty.

At 7 pm, Greene’s 3rd Brigade had hurriedly moved into the vacant trenches, but they were stretched thin trying to man its quarter-mile length. At that point, Steuart sent his infantry forward against Greene’s position. The defenders gamely opened fire, but the Confederates’ left flank charged the vacated diggings whose defenders had earlier marched off down the Baltimore Pike. After quickly securing these positions, the Rebels assailed Greene’s troops on the lower hill, who found themselves under attack from their front and right, as well as from behind a stone wall to their rear.

Ireland, commanding the 137th New York, pulled his troops back to the traverse above the saddle connecting the upper and lower hills. The gathering darkness aided the Federals as it partially cloaked their movement, but other Union forces on the heights mistook Ireland’s maneuver as a retreat and commenced falling back themselves. Realizing the implications, Yankee officers managed to halt what could have turned into a rout.

At that point, the 10th Virginia Infantry occupied the unmanned works on the south slope of the lower hill. Meanwhile, the 61st Ohio and 157th New York, unaware of the 10th Virginia’s presence, were advancing on the same point from the opposite direction with the intent of reinforcing Greene. Colliding with the Confederates in the darkness, the Yankees were initially driven back in confusion, but elements of the Union I Corps were trailing the Ohio and New York units and arrived in time to fight the Virginians to a standstill and secure Greene’s right flank.

By then the day’s fighting on Culp’s Hill started to fizzle out. Johnson suspected his foes were anticipating a night attack, so he forbade any further advances before dawn. He did not realize there were no Federal troops between his division and the Union rear on the Baltimore Pike. He did send a scouting party from the 1st Maryland (Confederate) Battalion to check for enemy movements. When these troops returned and reported seeing wagons moving along the pike, Johnson misconstrued this as a Federal retreat. It was actually a supply convoy. He decided to wait for daylight to finish off the Yankees.

Confederates now occupied the captured works and the lower hill from the saddle between the upper and lower hills south toward Spangler’s Meadow. Ireland had established a firm defensive line on the upper hill. Far from retreating, as Johnson believed, the Federals used the night hours to move the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry from Cemetery Ridge to reinforce their presence on Culp’s Hill. Around midnight, elements of XII Corps tried to return to their vacated diggings on the hill’s southeastern slope near Spangler’s Spring only to find them occupied by Steuart’s Rebels. Williams had assumed command of the Union XII Corps earlier that day when Slocum assumed control of the right wing of the Union army. Williams was unwilling to resume the chaotic nocturnal fighting, so he had the troops bed down in an open field in front of the trench and wait for dawn.

During the early hours of July 3, Williams laid plans to assault the Rebel positions on the lower hill at daybreak. Under cover of darkness he quietly moved artillery into position overlooking Spangler’s Meadow in such a way that it could, as soon as it was light enough, fire at virtually point-blank range into the Confederate diggings. Williams shifted his division, at that point led by Brig. Gen. Thomas Ruger, to a position on the southern perimeter of Spangler’s Meadow. A brigade of Geary’s division set itself up in an east-west line along the tree line bordering Spangler’s Lane. Another brigade, commanded by Candy, reinforced Greene’s troops. With the Federal attack scheduled for daybreak, the artillery was to open its preliminary barrage at 3:30 am.

Also during that busy night Walker eventually joined the attack, deploying his troops facing the Federals across Spangler’s Meadow. Two additional brigades from Rodes’ division of Ewell’s corps—led by Brig. Gen. Junius Daniels and Colonel Edward O’Neal—reinforced Johnson’s command on the right and center facing the upper hill. Brig. Gen. William “Extra Billy” Smith’s brigade of Early’s division forded Rock Creek to extend the Confederate left from Spangler’s Spring.

Lee’s plan for the morning of July 3 was to launch coordinated attacks on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Ridge, but Longstreet could not get his forces deployed in time. The Federals did not wait for him and opened up with their field pieces. One of the 1st Maryland (Confederate) Battalion’s officers, Major William Goldsborough, described the shelling: “To add to the horrors of the situation a battery or two opened upon the division at close range, and most of their shells fell among the men of Steuart’s brigade, who were compelled to closely hug the ground behind the breastworks for protection. A more terrible fire men were never subjected to, and it was a miracle that any escaped.”

Seeing what was happening to his troops Steuart, his face a river of tears, repeatedly sobbed, “My poor boys! My poor boys!”

The Union guns had opened fire promptly at 3:30 am, inflicting grievous casualties on the graybacks dug in on the lower hill. The shelling did not last long, though, as Lt. Col. Ariel Pardee’s 147th Pennsylvania Infantry charged across open ground (which since that day has been known as Pardee’s Field) and quickly routed the decimated defenders from behind their stone wall before they could draw beads in the gloom of late predawn. At 4 am the Yankees to the right also advanced but collided with a furious countercharge by the graybacks facing them, driving the Federals back in disorder. The Rebels attempted to follow up this success by launching several assaults on the northern positions on the upper hill, but each was driven back with heavy losses both from entrenched blue infantry and by fatally accurate shelling from Williams’ cannons above Spangler’s Meadow. By 6 am, the Rebels had ruefully broken off their charges up the upper hill.

“We tried again and again to drive the enemy from their position,” wrote Lt. Col. L.H. Salyer of the 50th Virginia Infantry. “But at length we were compelled to fall back, worn down and exhausted. At one time we were within a few feet of their works, but the fire was so heavy we could not stand it.”

At this point Williams ordered Colonel Silas Colgrove, commanding Ruger’s brigade, to make a reconnaissance foray in front of the Union right. Possibly due to a mix-up in communications, Colgrove instead ordered the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry and 27th Indiana Infantry to launch a direct assault on the Confederate positions facing them. When Lt. Col. Charles Mudge of the 2nd Massachusetts heard the directive, he remarked, “Well, it is murder, but it’s the order.” He sent his men across 100 yards of open field facing strong defensive positions.

The Massachusetts troops charged straight ahead across Spangler’s Meadow while the Hoosiers galloped across the field in a northwesterly direction. Both units were met by blistering musketry that stopped the 27th Indiana cold after it had traversed about one-third of the field’s length. The 2nd Massachusetts made it almost all the way across the field before piling up in front of Confederates who had set themselves up among a line of huge boulders. Both attacking elements were slowed by the meadow’s muddy ground, which hampered their mobility and made them easier targets. Also, just as the situation seemingly could not get worse for the blue soldiers, the defenders were reinforced by a brigade of Smith’s Virginians. The bluecoats gamely held on until running out of ammunition, and then the survivors fell back. The sole result of this mistaken charge was that these two Union regiments were decimated to the point of uselessness.

Immediately before the charge of the Indiana and Massachusetts regiments, the 1st Maryland (Federal) Potomac Home Brigade under Brig. Gen. Henry Lockwood had advanced at a gallop from the Baltimore Pike to Spangler’s Meadow. This inexperienced unit did fairly well versus stout opposition, endangering the rather thinly held Confederate line bordering Pardee Field. However, the Marylanders became confused and halted, thinking they were attacking their own troops when they saw a number of blue soldiers crossing from right to left in front of them. This was actually the ill-fated charge of the 2nd Massachusetts. Lockwood led his men back to the Baltimore Pike, aborting a charge that might well have rolled up the sparsely manned Rebel line.

By 6 am, both sides had settled into a heavy exchange of musketry between lines that were not widely separated. Two hours later, Johnson commenced a series of attacks all along the battle line. These were beaten back, with the commands of Daniels, Williams, and Steuart taking heavy losses from both small arms and artillery as Greene rotated regiments in and out of the breastworks, enabling them to maintain a high rate of fire. At 10 am, Johnson launched his final assault with Steuart’s brigade charging from the southern border of Pardee’s Field. This unfortunate unit again suffered ghastly losses from enfilading artillery fire and riflemen that sent surviving gray soldiers back in disordered retreat. To the right of Steuart’s troops, the 1st Maryland (Confederate) Battalion and 3rd North Carolina Infantry advanced through a wooded area that afforded some cover, but these units could only advance as far as the saddle between the upper and lower hills before being stopped cold by Williams’ artillery.

The last significant Confederate attack kicked off at 10 am as the Stonewall Brigade and Daniels’ brigade charged Greene’s positions from the east while Steuart’s brigade advanced across open ground toward the position of Candy’s and Kane’s brigades on the upper hill, where the Federals had been too busy fighting during the past 24 hours to throw up breastworks. In the face of accurate and well-coordinated artillery and rifle fire, both attacks were beaten off with heavy losses. About this same time, the inexperienced 1st Maryland (Federal) Potomac Home Brigade was bloodily repulsed while trying to take a stone wall traversing the open field parallel to the line of works. Candy hurriedly sent his 147th Pennsylvania Infantry to reinforce the Marylanders, enabling them to carry the field and secure the wall. Yet, the drama continued for the moment.

Williams later described the Confederates’ hysterical counterattacks: “The wonder is that the Rebels persisted so long in an attempt that the first half hour must have told them was useless.”

Displaying a fanaticism that astounded and horrified the Northerners, Johnson repeatedly sent his eager troops against the stout Union defenses. O’Neal later wrote that his brigade “charged time and again up to their works, but were every time compelled to retire. Many gallant men were lost.”

Johnson’s division lost about 2,000 men, nearly a third of its complement. Another 800 from reinforcing units fell on that grisly July 3. During July 2 and 3, the Union XII Corps lost approximately 1,000 men. Many more lives would be lost in the months to follow, but the success of Greene’s brigade atop Culp’s Hill contributed substantially to the eventual end of the bloody Civil War between the North and the South.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments