By William E. Welsh

Deep snow blanketed the steppes surrounding the northeastern Ukrainian city of Kharkov on February 6, 1943. The soldiers of Major Kurt Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion of SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler shivered from the cold. The half-tracks and assault guns were concealed in a belt of woods outside the village of Malinovka on the east bank of the Donets River not far from the railroad depot at Chuguyev. Outside the wind howled. Hardly a word was spoken by the men as they watched tanks and infantry at the head of a Russian column work their way slowly toward them.

Meyer had instructed the crews of the dispersed vehicles not to fire until he gave the order. Meyer had been sent across the Donets to cover the retreat of the remnants of the German 298th and 320th Infantry Divisions, which had been shredded by the spearheads of Soviet armies participating in a major attack along the entire southern sector of the Eastern Front.

That morning as many as 1,400 survivors of the two decimated German divisions had marched through Malinovka on their way to the safety of the main German line at Chuguyev. The survivors were a pitiful sight. Many had fingers and toes black from frostbite. Swaddled in blankets and rags in an effort to protect themselves from snow squalls and subfreezing temperatures, the half dead soldiers bore little resemblance to Meyer’s panzergrenadiers, who had arrived at the front by train less than a week earlier.

The ground sloped uphill toward the advancing Russian column, giving the German gunners clear targets silhouetted against the sky. Russian T-34 and KV-2 tanks clanked slowly forward and brown-uniformed infantry followed cautiously, letting the steel monsters lead the way.

“We observed the shadows of the Russian tanks slowly working their way west to the right and left of the road,” wrote Meyer. “The tanks avoided the road, snaking across the deeply furrowed landscape, obviously trying to take our bridgehead in a pincer movement and crush it in their armored jaws.”

Meyer’s battalion of armored vehicles was supported by 88mm guns on the west bank of the Donets at Chuguyev. Between his vehicles and the artillery beyond the frozen river, there would be more than enough firepower to severely damage the Russian tank column.

The radio silence was broken periodically as officers stationed at other points reported the Russian column’s progress. “The Red Army soldiers—drunk with victory—were going to deliver their own death sentence,” wrote Meyer. “I was in contact with all the units, either by radio or telephone. The units could respond in a fraction of a second and were convinced of their power. They had not been gripped by fear of the Russians.”

Meyer waited until the attackers were on top of the German position. At 150 meters, he gave the order to fire. Shells from German antitank guns and armored vehicles streaked toward their targets. Meyer’s ambush caught the Russians completely by surprise. Smoke and flames rose from Russian tanks that ground to a halt in the snow. The white landscape was littered with the corpses of Russian soldiers. “The harvest of death was grisly,” Meyer wrote.

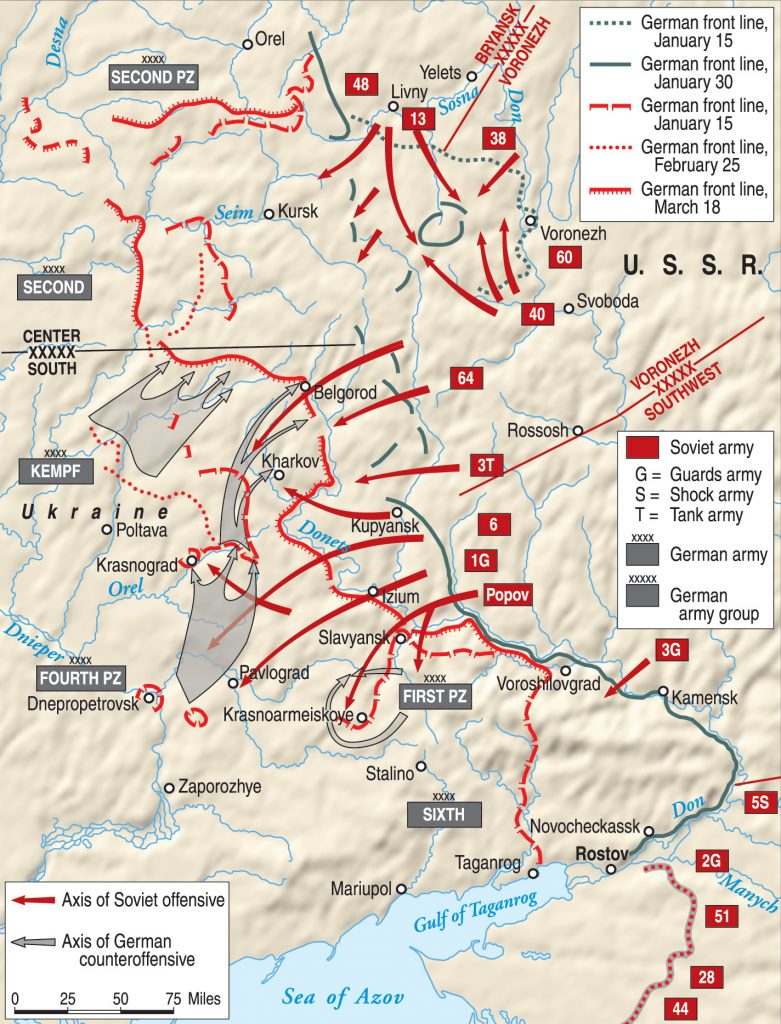

Meyer’s battalion suffered only 17 casualties in the firefight, while the Russians lost 250 men and several tanks. The skirmish was a delaying action in the face of the overwhelming advantage enjoyed by the southern wing of Col. Gen. Filipp Golikov’s Voronezh Front, one of three Soviet fronts that attacked German forces in southern Russia the first week of February 1943. That same week, the last remnants of the German Sixth Army trapped in Stalingrad surrendered.The Voronezh Front had been involved in one offensive after another since December 21, 1942, and when its northern and southern wings were ordered to strike toward Kursk and Kharkov, respectively, as part of Operation Star, its armies had not been able to rest and reorganize.

Believing that the Germans in southern Russia were deeply demoralized after the destruction of the Sixth Army, STAVKA, the Soviet high command, ordered Golikov’s Voronezh Front, Col. Gen. Nikolai F. Vatutin’s Southwestern Front, and Col. Gen. Andrei Yeremenko’s Southern Front to advance together against the German southern wing in the Ukraine. As envisioned by STAVKA, Golikov and Vatutin would outflank the Germans in northeastern Ukraine and then turn south to cut the Nazi invaders off from the bridges over the Dnieper River. If everything went as planned, STAVKA believed that it might achieve a grand encirclement of the German forces operating in the Ukraine. It was a highly ambitious undertaking, and one in which the Soviet planners neglected just about every logistical consideration that needed to be addressed if it was to be achieved.

Golikov received orders on January 23 instructing him to capture Kharkov. The Soviets had tried to retake the city in May 1942, but failed. Three days later the orders were revised to include the capture of Kursk, which lay 200 kilometers north of Kharkov.

Kharkov, a major railroad hub and industrial center, was the second largest city in the Ukraine and the fourth largest in the Soviet Union. In the wake of the collapse of the Hungarian Second Army, the German high command began to send reinforcements to bolster Army Detachment Lanz, which was part of Army Group B. Army Detachment Lanz was responsible for a section of the Eastern Front running from Belgorod to Izium, and thus covered all approaches to Kharkov.

Colonel General Maximilian Weichs led Army Group B. General Hubert Lanz, who commanded the army detachment that bore his name, reported to Weichs.

The first of the fresh troops to arrive belonged to Maj. Gen. Walter Hornlein’s motorized Grossdeutschland Division, which after earning a much-needed rest and undergoing a major reorganization began arriving in the sector in mid-January. Also dispatched to the sector was the newly created SS Panzer Corps under Lt. Gen. Paul Hausser, which comprised the Das Reich, Leibstandarte, and Totenkopf panzergrenadier divisions.

In addition to the Grossdeutschland Division and the SS Panzer Corps, Lanz had several infantry divisions, including the 168th, 298th, and 320th. Unlike the German infantry divisions, which had horse-drawn artillery and no vehicles to transport their foot soldiers, the Grossdeutschland Division had half-tracks and trucks that could shuttle its battalions back and forth to respond to emergencies as they developed.

Golikov tasked three of his five armies with the drive on Kharkov. Lt. Gen. Kirill Moskalenko’s 40th Army would advance toward Belgorod and, once it captured that city, continue in a southwesterly direction so that it encircled Kharkov from the north. In the center, Lt. Gen. M.I. Kazakov’s newly formed 69th Army was to advance toward Kharkov, establish bridgeheads across the Donets, and then push into the city from the east. The strongest of the three armies, Lt. Gen. Pavel Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army, was to cross the Donets south of Kharkov and encircle the city from the south.

Moskalenko’s northern pincer and Rybalko’s southern pincer were to meet at the railroad town of Lyubotin, a short distance southwest of Kharkov. The distance from the starting point of the Soviet attack to Kharkov was about 120 kilometers.

Golikov had 200,000 men to Lanz’s 50,000 men. The Soviet rifle divisions were greatly reduced from continual operations, and they averaged 4,000 to 6,000 men. The three Soviet armies advancing on Kharkov had about 315 tanks, and the front as a whole had another 300 in reserve. The Germans had about 200 tanks, most of which were with the SS panzergrenadier divisions. The Grossdeutschland Division was seriously deficient in armor. When the Soviet attack began, the division had only 31 tanks, more than half of which needed repairs before they could return to action. The one major advantage the Germans had in the approaching campaign was that they retained control of the skies and could launch tactical air strikes with their Stuka dive-bombers against Soviet tank columns.

Army Detachment Lanz was just being established as Operation Star began. Corps Cramer, comprising the 168th and Grossdeutschland Divisions under the command of Lt. Gen. Hans Cramer, shielded Kharkov from the north. Two divisions of the SS Panzer Corps, both of which arrived just as the Soviet attack got underway, protected Kharkov from the east and south. The Das Reich and Leibstandarte Divisions detrained at Kharkov just in time to prevent the Soviets from pushing unopposed into Kharkov from the east. Lanz immediately fed the two divisions into the battle. They would remain in supporting distance of each other throughout the battle and frequently shared infantry and armor. The Totenkopf Division did not begin arriving in the vicinity of Kharkov until about 10 days after the battle had begun. Southeast of Kharkov, Colonel Herbert Michaelis’s 298th Infantry Division was posted behind the Oskol River from Kupyansk to Ssenkovo, and Lt. Gen. Georg Postel’s 320th Infantry Division was deployed from Ssenkovo to Izium.

Golikov’s timetable called for the 69th Army to secure river crossings over the Donets River at and above Volchansk by Febuary 5. The Soviet 161st and 219th Rifle Divisions, which formed the right wing of the 69th Army, ran into considerable opposition on the second day of the attack. At Veliko-Mikhailovka, German soldiers had transformed the village into a strongpoint. The fighting would rage for three days at Veliko-Mikhailovka against Germans who were determined to buy as much time as possible before falling back. On February 6, the elements of the Grossdeutschland Division defending the village retreated to the southwest through a narrow corridor that remained open.

The left wing of Kazakov’s army, which comprised the 180th and 270th Rifle Divisions, attacked toward Volchansk. The two Soviet divisions encountered light resistance until 48 hours into the offensive when they ran headlong into stubborn opposition from Colonel Heinz Harmel’s Deutschland Regiment of Maj. Gen. Georg Keppler’s Das Reich Division, which held a 30-kilometer front east of the Donets River. The fighting intensified when Colonel Otto Kumm’s Der Führer Regiment of the Das Reich Division went into action on February 5 on Harmel’s left flank. Kumm launched a bold counterattack against Maj. Gen. I.Y. Maloshitsky’s 180th Rifle Division on February 6 that drove the startled Russians back eight kilometers and forced them to spend precious time the following day regaining ground previously occupied.

After his forces captured Veliko-Mikhailovka, Kazakov was able to shift the bulk of the troops from his right flank to the drive on Volchansk. The 69th Army finally captured the town on February 9, four days behind schedule. The capture of Volchansk was made possible in part because Lanz had ordered the two regiments of the Das Reich Division to pull back across the Donets when Moskalenko’s 40th Army captured Belgorod on February 9, outflanking Keppler’s grenadiers.

Rybalko was a talented commander of armored forces, and his army had three tank corps: Maj. Gen. M.I. Zenkovich’s 12th Tank Corps, Maj. Gen. V.A. Koptsov’s 15th Tank Corps, and Maj. Gen. S.V. Sokolov’s 6th Guards Cavalry Corps. The 12th and 15th Tank Corps each comprised three tank brigades, and both were considerably stronger than Sokolov’s corps. Rybalko also had four standard rifle divisions and reserve armor in the form of the 179th Tank Brigade and 201st Tank Regiment.

The right wing of Rybalko’s army became engaged with Harmel’s grenadiers at the outset of the attack in a heated battle for the village of Veliky Burluk. When Kumm’s regiment went into action alongside Harmel’s regiment, it allowed Harmel to counterattack Maj. Gen. M.N. Mokovchuk’s 48th Guards Rifle Division. Incensed by the audacity of the Germans, Rybalko sent Koptsov’s 15th Tank Corps against Harmel’s tenacious grenadiers. Meanwhile, the 6th Guards Cavalry and 12th Tank Corps continued their advance toward the wide bend in the Donets south of Kharkov.

On the same day Rybalko’s army launched its attack, Lt. Gen. Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Leibstandarte Division detrained at Chuguyev. Dietrich sent a portion of his division, including Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion and part of Colonel Fritz Witt’s 1st Regiment of the division, across the Donets to assist the withdrawal of the retreating 298th and 320th Infantry Divisions.

Rybalko’s tank units had secured some stretches of the east bank of the Donets on February 4, but they would not be ready to attack across the river until the infantry and heavy artillery at the back of the long columns caught up with the armor. By February 9, Koptsov’s 15th Tank Corps was preparing to cross at Pechenegi, and Zenkovich’s 12th Tank Corps was ready to do the same at Chuguyev. In the meantime, Rybalko order Sokolov to shift his forces farther downstream and attempt to cross the Donets at Zmiev, which was unoccupied.

Because his forces were busy mopping up the Hungarian Second Army, Moskalenko did not begin his advance southwest toward Belgorod until February 3. After Operation Star had been underway for several days, Golikov ordered Moskalenko to speed up his attack on Belgorod to compensate for the slow progress of Kazakov’s 69th Army and Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army. In response to the request, Moskalenko paired two independent tank brigades assigned to his army with two of the rifle divisions advancing on Belgorod. As a result, Moskalenko’s army had two mobile groups that could reach their objective faster and hit the defenders harder than if attacking without armor support.

The defense of Belgorod initially was the responsibility of the German 168th Infantry Division. However, it quickly became apparent to Lanz that it could not contend with the vastly superior Soviet forces arrayed against it. Lanz therefore ordered the 168th Division to deploy west of Kharkov to the village of Tomarovka in an effort to block Moskalenko’s right wing. To compensate for the removal of the 168th from the fighting at Belgorod, Lanz shifted the Grossdeutschland Division’s two regiments west. This left the division’s grenadier regiment on the left flank covering the northern approaches to Kharkov, and the division’s fusilier regiment on the right flank covering Belgorod.

By February 7, the two mobile groups established by Moskalenko had reached the outskirts of Belgorod. Fighting raged around the clock for two days until the Germans were finally forced to pull out on February 9.

The cumulative effect of having three Soviet fronts attacking toward the Dnieper River created an ominous situation that fell squarely, not on the shoulders of Army Group B commander Weichs, but instead on the shoulders of Army Group Don commander Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, who was responsible for the German forces under attack by Vatutin and Yeremenko. Manstein received Hitler’s permission to pull back some of his forces and deploy his armored assets as he saw fit without interference from the high command. Manstein subsequently shifted Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army from the right flank of Army Group Don to its left flank to better resist the Soviet onslaught.

The most significant outcome of the meeting was Hitler’s approval of Manstein’s request that he be given control of Army Detachment Lanz so that one commander could coordinate the movements of all German forces in southern Russia. Five days later, on February 12, Manstein became commander of the newly established Army Group South. Army Group B, which ceased to serve a real function following the Battle of Stalingrad, was eliminated. Thus, midway through the Soviet 1943 winter offensive in southern Russia, Hitler gave Manstein control of 32 German divisions manning a 700-kilometer front.

The progress of the Soviet attack on Kharkov accelerated rapidly before Manstein had actual control of Army Detachment Lanz. On February 7, Sokolov’s 6th Guards Corps was across the Donets at Zmiev. From there, Sokolov’s forces advanced northwest through the Mzha Valley toward Merefa. Three days later, despite stubborn resistance from elements of Dietrich’s grenadiers, both the Soviet 12th and 15th Tank Corps had also crossed the Donets.

The situation at Kharkov for Army Detachment Lanz had grown critical once Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army had crossed the Donets. In the north, it fell to Corps Cramer to hold back Moskalenko’s 40th Army. It became clear that the 168th Infantry Division was no longer an effective fighting force, leaving General Walter Hornlein’s Grossdeutschland Division to fight alone against Moskalenko’s 40th Army. Hornlein stretched his line as much as possible, but Moskalenko’s line overlapped it, extending as far as 40 kilometers west of Kharkov.

By February 11, Hornlein’s reconnaissance battalion on the division’s right flank had been driven back to the northeastern corner of Kharkov. Fortunately for Hornlein, the Das Reich Division had fought Kazakov’s 69th Army to a standstill. Kumm’s Der Führer Regiment of the Das Reich Division subsequently redeployed south of Kharkov to fight the 6th Guards Cavalry Corps, while Harmel’s Deutschland Regiment remained behind to slow the advance of Kazakov’s 69th Army.

On February 12, Rybalko attacked along his entire front. While the 15th Tank Corps and two rifle divisions attacked east from their bridgehead at Pechenegi toward Kharkov, the 12th Tank Corps and one rifle division advanced from their bridgehead at Chuguyev toward the city from the southeast. At the same time, Sokolov’s 6th Guards Cavalry Corps continued its advance in a wide arc south of Kharkov toward Lyubotin.

Sokolov’s troops needed to control two towns en route to Lyubotin to keep a supply corridor open for fuel and ammunition. On the north side of their advance was the key town of Merefa, and on the south side was the town of Novaja Vodolaga.

During the night of February 11-12, Das Reich’s motorcycle battalion, led by Colonel Jakob Fick, arrived on the outskirts of Novaja Vodolaga. Backed by a handful of Panzer IVs to cover his flanks, Fick led his dismounted grenadiers in an attack on the town the morning of February 12. Fick’s grenadiers drove the Russians out, but a counterattack retook the town. The following day Fick’s grenadiers, backed by additional tanks from both the Das Reich and Leibstandarte Divisions, captured the town, forcing the Russians to retire south.

Just to the north, fighting raged in the town of Rogan southeast of Kharkov as Zenkovich’s 12th Tank Corps sought to overwhelm the defenses of two battalions of Witt’s 1st Regiment of the Leibstandarte Division. The Soviets fired Katyusha rockets and 120mm mortars, followed by Soviet infantry attacks supported by T-34s. The Germans eventually were forced to abandon the town to the Russians.

On February 13, the lead elements of the last division of Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps, Lt. Gen. Theodor Eicke’s Totenkopf Division, detrained at Poltava. Since Poltava was 140 kilometers southwest of Kharkov, the badly needed reinforcements would not have an immediate effect on the battle. The following day, Koptsov’s 15th Tank Corps reached the factory district located in eastern Kharkov and fought building to building against Dietrich’s grenadiers, but Zenkovich’s 12th Tank Corps, on Koptsov’s left flank, was still 10 kilometers from the city’s edge.

Although Hitler had ordered that Kharkov be held to the last man, Hausser had no intention of seeing his elite corps destroyed for no good reason. That day Hausser ordered Dietrich to demolish the key bridges inside the city to slow the advance of Rybalko’s units, which already were moving slowly into the eastern part of the city.

Manstein sent orders to Lanz at daybreak on February 14 that Kharkov was to be held in compliance with Hitler’s orders. After receiving the orders, Lanz forwarded them to Hausser, instructing Hausser to cancel his orders to begin blowing up the bridges inside Kharkov.

That same day, Manstein also appointed Col. Gen. Erhard Raus as the new commander of Corps Cramer, which thereafter became known as Corps Raus. Raus had the unenviable job of commanding the badly mauled Grossdeutschland Division and the demoralized 168th Infantry Division. Raus shared with Hausser the responsibility for keeping a corridor open to the southwest should Hitler change his mind and allow those parts of Army Detachment Lanz inside the city to retreat to safety.

On February 14, the SS Panzer Corps continued its attacks on Surzhikov’s 11th Cavalry Division. After the fighting at Novaja Vodolaga, the Russians had fallen back to the village of Ochotschaje. Two battalions of Kumm’s Der Führer Regiment backed by tanks and assault guns were able to secure the city, and Surzhikov’s troops withdrew southeast to Bereka. The capture of Ochotschaje by the Germans ensured once and for all that Sokolov’s 6th Guards Cavalry Corps would not complete its objective of linking up with Moskalenko’s 40th Army.

On the afternoon of February 14, Hausser received an urgent message from Das Reich Division commander Brig. Gen. Herbert Vahl, who had replaced the seriously ill Keppler on February 10, informing Hausser that the division had no more reserves to commit to the multiple breaches in its battle lines that occurred that day. Despite admonitions by Manstein and Lanz that the Das Reich Division, namely Harmel’s Deutschland Regiment, should continue to defend Kharkov even if faced with annihilation, Hausser ordered Vahl to begin an orderly retreat toward the southwest corridor that evening.

When Lanz learned of Hausser’s orders to Vahl to begin disengaging, Lanz reiterated that the Das Reich Division was to continue to defend the city. Hausser rescinded his order, but he knew full well that Harmel’s Deutschland Regiment had already begun to disengage.

On February 15, the Soviet forces around Kharkov redoubled their attacks on German forces defending the city. Zenkovich’s 12th Tank Corps and Maj. Gen. G.M. Zaitsev’s 62nd Guards Rifle Division finally broke into Kharkov’s southeast quadrant where they battled elements of the Leibstandarte Division. To the immediate north, other parts of the Leibstandarte Division battled Koptsov’s 15th Tank Corps in the factory district. Further north, Harmel’s Deutschland Regiment of Das Reich found its lines assailed by units from three rifle divisions belonging to Kazakov’s 69th Army.

By that time, the left wing of Moskalenko’s 40th Army, engaged with Hornlein’s Grossdeutschland Division, had already entered the northern edge of the city, where Kharkov’s enormous Red Square was located. Simultaneously, Kravchenko’s 5th Guards Tank Corps on Moskalenko’s right wing was approaching Lyubotin, threatening to cut off the two-kilometer- wide corridor through which Hausser hoped to withdraw Harmel’s Deutschland Regiment.

At 11 am on February 15, Lanz wired Manstein informing him that the situation was dire and requesting permission to withdraw the troops that were still inside Kharkov. Although Manstein sympathized wholeheartedly, he was reluctant to go against Hitler’s orders. However, Manstein wired orders to Lammerding to move the Thule Regiment of the Totenkopf Division as fast as possible to Lyubotin to reinforce Corps Raus.

With Soviet troops pushing toward the center of Kharkov from the north and east, Hausser instructed Harmel at noon on February 15 to lead his regiment out of the city through the southwest corridor. When Soviet T-34s started to pursue them, they were ambushed by German tanks and assault guns left behind to slow the enemy’s pursuit. The German crews were able to knock out 15 Russian tanks. The last German unit to leave the city was the Grossdeutschland’s grenadier regiment. It was the regiment’s assault gun battalion that kept the Russians at bay while the grenadiers withdrew safely in their half-tracks and trucks.

Meanwhile, a battle raged on February 15 around Bereka as parts of Kumm’s Der Führer Regiment of the Deutschland Division and a battle group consisting of elements of the Leibstandarte Division that had left the city a number of days earlier continued to hound Sokolov’s 6th Guards Cavalry Corps.

When Hitler learned that Hausser had withdrawn his troops from Kharkov against orders, he directed his wrath not at Hausser, but toward Lanz. Hitler was not inclined to sack a high-ranking SS field officer, but he had no qualms about removing a German Army officer. In Lanz’s place, Hitler on February 16 appointed General Werner Kempf as the new leader of the army detachment, which was known thereafter as Army Detachment Kempf.

That same day, while the Russians secured Kharkov, Army Detachment Kempf reformed facing northeast on a new battlefront that stretched west to east from Okhtyrka to Borova to prevent a southwest push by the Voronezh Front toward the Dnieper River crossings over which supplies flowed to Manstein’s Army Group South.

What Manstein knew because of his keen intuition, but which STAVKA chose to ignore, was that the forces of both the Voronezh Front and Southwestern Front were so depleted of armor, manpower, and fuel that they were greatly overextended. Even if they cut the two railroads supplying Army Group South, it was unlikely that they could capture and hold the Dnieper River crossings. In blind pursuit of those very objectives, though, STAVKA ordered Golikov’s 40th and 69th Armies to push toward Poltava and Rybalko 3rd Tank Army to cover Kharitonov’s right flank.

On February 17, Hitler and his top aides arrived by plane at Manstein’s headquarters at Zaporozhye on the Dnieper to discuss strategy. The German leader, furious that Kharkov had been abandoned despite his explicit orders that it be held to the last man, stayed for three days. Even before Hitler had departed, Manstein had reorganized his forces for a bold counterstroke designed to catch the Russians off balance.

The spearhead of Vatutin’s Southwestern Front during the late winter offensive of 1943 had been Mobile Group Popov, an armored strike force comprising four Soviet tank corps under the command of Lt. Gen. Markian Popov. Manstein’s first objective was to crush Vatutin’s Southwestern Front and drive it back to its starting point east of the Donets. To do this, Manstein intended to use Col. Gen. Eberhard Mackensen’s 1st Panzer Army, Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army, and Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps.

On February 19, Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps assembled for the attack near Krasnograd, while General Otto von Knobelsdorff’s 48th Panzer Corps and General Friedrich Kirchner’s 57th Panzer Corps went into position northwest of Krasnoarmeiskoye. The 40th Panzer Corps of Mackensen’s 1st Panzer Army formed up south of Krasnoarmeiskoye.

Stuka dive bombers from Field Marshal Wolfram Richthofen’s Fourth Air Fleet screamed down on Popov’s and Kharitonov’s columns, softening them up for the German armor. When attacked, the Soviet spearheads were within 25 kilometers of the Dnieper and close enough to force Manstein’s headquarters staff at Zaporozhye to prepare for battle in case the Russians reached them that day.

Popov’s battle group could only muster about 50 working tanks, and it was heavily outgunned by the German forces arrayed against it. While Mackensen isolated Popov’s battle group, Hoth’s two panzer corps carved up Kharitonov’s 6th Army over a period of five days. Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps, which had been pulled back from the front line to rest and refit after the fall of Kharkov, returned to battle on February 23. The three SS divisions swept southeast and added to the mauling of the beleaguered Soviet 6th Army.

Although too late to mitigate the destruction of Kharitonov’s 6th Army, STAVKA on February 22 ordered Golikov to redirect the 69th Army and 3rd Tank Army toward Poltava and Krasnograd, respectively. This meant that Moskalenko’s 40th Army would be responsible for most of the territory around Kharkov and would have to fight Corps Raus alone. The decrease in pressure against his corps enabled Raus to order the Grossdeutschland Division to pull out of action on February 23 and refit at Poltava.

Vatutin’s Southwestern Front was in full retreat by February 28. To relieve the pressure on Vatutin, STAVKA transferred Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army from the Voronezh Front to the Southwestern Front. Vatutin ordered Rybalko to advance south and attempt to open a corridor to part of Kharitonov’s 6th Army, encircled by the Germans at Kegichevka, a town east of Krasnograd. Rather than rescuing the 6th Army, Rybalko’s troops were only marching to their own doom. The Das Reich and Totenkopf Divisions immediately attacked Rybalko’s 3rd Army. While Koptsov’s corps was encircled and annihilated, Zenkovich successfully led his corps in a fighting withdrawal northwest.

Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps had hit Rybalko’s corps hard from two directions and in 48 hours of desperate fighting had mauled the two tank corps and three rifle divisions. By March 5, Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army had switched over to the defensive and formed a new line facing southwest from Novaya Vodolaga to Ochotschaje. The same day the armies of Kazakov and Moskalenko also halted offensive operations.

After the destruction of the Southwestern Front, Manstein ordered the 48th Panzer Corps north to reinforce Army Detachment Kempf in preparation for an attack on Golikov’s forces. No sooner had the Voronezh Front gone over to the defensive than the Germans attacked it.

Manstein began the second phase of his attack with an assault by the SS Panzer Corps and 4th Panzer Army against the left flank of the Voronezh Front south of Kharkov. His plan was to annihilate once and for all Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army, which would enable the Germans to gain the rear of Golikov’s other two armies east of Kharkov and cut off their retreat. From west to east, the German forces included Army Detachment Kempf, SS Panzer Corps, and 48th Panzer Corps. The attack began on March 5 when three German panzer divisions—Das Reich, Leibstandarte, and Lt. Gen. Walther Hunersdorff’s 6th Panzer Division of the 48th Panzer Corps—slammed into Rybalko’s forces while they were still reforming south of Kharkov.

The following day, the refitted Grossdeutschland Division joined Corps Raus, part of Kempf’s forces deployed west of Kharkov. The same day, the Totenkopf Division, which had been busy mopping up the encircled Soviet 15th Tank Corps, took up a position on the left flank of Hausser’s battle line. In the fighting on March 6, the Das Reich Division retook Novaya Vodolaga.

By March 8, the SS Panzer Corps and 4th Panzer Army had captured the key railroad towns of Novaya Vodolaga and Taranovka, forcing the remnants of Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army to fall back toward Lyubotin and Merefa. By that time, Rybalko had used up nearly all his tanks and had to rely on artillery to hold back the German armored divisions that were butchering his forces. At Merefa, Rybalko massed nine artillery batteries to contest the German advance north. By that time, Manstein had sent the 11th Panzer Division from the 1st Panzer Army north to reinforce the two divisions of Knobelsdorff’s 48th Panzer Corps.

The following day, the SS Panzer Corps captured Lyubotin when the Leibstandarte Division surrounded it from the north and the Das Reich Division pushed into it from the south. The capture of Lyubotin drove a 20-kilometer wedge between Kazakov’s 69th Army and the remnants of Rybalko’s 3rd Tank Army. While Knobelsdorff’s panzer forces mopped up the remnants of Rybalko’s army at Merefa, Hausser ordered his SS divisions to join Corps Raus in an assault to recapture Kharkov.

On March 10, the Grossdeutschland Division, spearheading an all-out attack by Corps Raus against Moskalenko’s overextended 40th Army, swept north to retake Belgorod. That same day, Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps shifted west to support Corps Raus, and Dietrich’s Leibstandarte Division captured Dergachi.

Resistance from Moskalenko’s 40th Army had melted away, and Hausser’s SS Panzer Corps was able to swing west around Kharkov. Dietrich’s Leibstandarte Division entered Kharkov from the north on March 11, while Vahl’s Das Reich Division pushed into the city from the west. When Maj. Gen. E.E. Belov, the Soviet commandant of the city, shifted his forces north the following day to battle the Leibstandarte Division, he uncovered the west side of the city, allowing the Das Reich Division to advance unopposed toward its center. On March 13, Belov ordered a fighting withdrawal to the east.

Manstein, through the clever shifting of his forces, had managed in less than a month to drive the Soviet forces in southern Russia back to the starting points of their late winter offensives. In the process, he had destroyed upwards of five armies and crippled several others. The successful counterattack gave the troops of Army Group South a significant boost, which they would need for the titanic clash at Kursk in the summer of 1943.