By Martin J. Dougherty

More or less in the center of the Mediterranean Sea, Malta became one of the most strategic locations in all of World War II. As a powerful threat to Axis operations in the Mediterranean, it was under near-constant attack from 1940-1942, before the Allies could break the siege from sea and air.

Yet in and of itself, Malta was merely a small group of islands close to Italy, of no great value to the Axis as a base and with no industrial contribution to make. It was only when Italy’s Benito Mussolini launched his North African campaign that Malta became so critical as a platform for Allied operations that Prime Minister Winston Churchill reportedly said that if Malta fell, he would strive for the best possible terms of surrender.

The Allied position in the early months of the war was complex. The German invasion of Norway in April 1940 was followed by an advance into Belgium and France in May, presenting a clear and immediate threat to the British Isles. Already lagging behind in the race to rearm, Britain needed to look to her home defense—yet at the same time she had a worldwide empire to defend.

Egypt was critical to the Allied war effort and potentially to that of the Axis. Control of the Suez Canal was vital to a maritime strategy which called for warships to be transferred to the Pacific if war with Japan broke out and to the movement of supplies and troops from India and other parts of the Empire. If the Suez Canal could not be used, Allied shipping would be forced to make the longer voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, tying up more merchant tonnage for longer at a time when losses from Nazi U-boats were mounting.

Air power based in Italy, and the threat of attack by the Italian navy, made the Mediterranean extremely hazardous for Allied shipping. The threat was sufficient to require heavily defended convoys. However, while control of the sea was disputed these air and naval assets were tied down. The loss of Malta would reduce the Allies’ ability to challenge Italian control of the Mediterranean, while if Egypt fell, all the assets tied up in the contest would be freed for use elsewhere.

Control of Egypt also potentially granted access to the oil fields of Iraq, which were coveted by the Axis powers. With their assistance, a coup in 1941 temporarily created a pro-Axis state which was ultimately defeated by minor Allied forces based there. The loss of Egypt would have permitted Axis intervention and more than likely made the situation permanent. At the same time, Axis possession of Egypt would have threatened Allied oil supplies from the Middle East. Malta was key for the defense of Egypt, though not always directly.

Unified into a country in 1861, Italy came late to the colonial scramble but managed to obtain holdings in North Africa. Expanding these and gaining new territories was a driving factor for Mussolini. He began in 1935 with an invasion of Ethiopia, and in 1939 Italy launched a campaign against Albania. This was rapidly successful, giving Italy control over the entrance to Aegean Sea.

Italy entered World War II in June 1940, and began making preparations for a campaign into North Africa. Understrength and lacking some equipment, Allied forces in Egypt had to contend with the possibility of attack from two directions. A direct advance into Egypt was possible from Libya and forces positioned in the Italian colonies in Somaliland, Eritrea and Ethiopia threatened British Somaliland.

In early August 1940, Italian and local troops seized British Somaliland. Though it was a blow to British prestige, the defenders were evacuated by sea and made available elsewhere. Indeed, it can be argued that the loss of British Somaliland improved the strategic position for the Allies by doing away with the need to defend a low-value area.

Success in British Somaliland also freed up Italian forces for a possible push through French Somaliland and into Egypt, and while this threat never materialized, Allied commanders had to account for the possibility. In the meantime, Italian forces in Libya launched their offensive in September. After managing to advance as far as Sidi Barrani, a pause was necessary to build up supplies for a renewed attack. As the Italians dug in, the British planned an attack.

The Allied counteroffensive began in December. Italian resistance collapsed in the face of armored assaults and flanking movements. The Italian armored force was largely equipped with tankettes, which had proven effective in the Spanish Civil War and subsequent minor conflicts. But they were no match for real tanks and the Italian army was soon in full retreat.

British propaganda made much of the Italian collapse, creating a lasting impression that Italian troops lacked courage. This was not the case, though they were unenthusiastic about the war they had been sent to fight. Overmatched in equipment, particularly armored vehicles, and dangling at the end of a long supply line, the Italian force was impressive on paper but unprepared for the conflict in which it found itself engaged.

Thus began a long retreat over the narrow coastal strip of North Africa. With the terrain inland unsuited to vehicles, the coast route was the only viable avenue of advance or retreat. The North African campaign would see Allied troops harry their enemies one way then be forced back along the same route—back and forth until the tide finally turned. For now, however, the pursuit broke the Italian force. By early February, the Allies had defeated their opponents at El Agheila and taken well over 100,000 prisoners.

Malta’s value as a base for air and maritime forces was readily apparent. If the convoy route could be kept open, Malta offered the chance to provide air cover; if not, then its aircraft could assist in the struggle for control of the Mediterranean. At this point in the conflict the capabilities of aircraft against major warships were not fully appreciated, but the sinking of the German light cruiser Konigsburg in April 1940 might have suggested the role air power was to play.

Malta was ideally placed to support such operations against the Italian fleet, but there were grave doubts as to whether the island could be held against attack. In the 1930s, British military thinkers decided that Malta was highly vulnerable in any future war and relocated the Mediterranean Fleet to Alexandria, in Egypt. Little effort was made to prepare the island for defense, as this was deemed a waste of resources. This position was revised in July 1939, with a decision to send additional antiaircraft weapons.

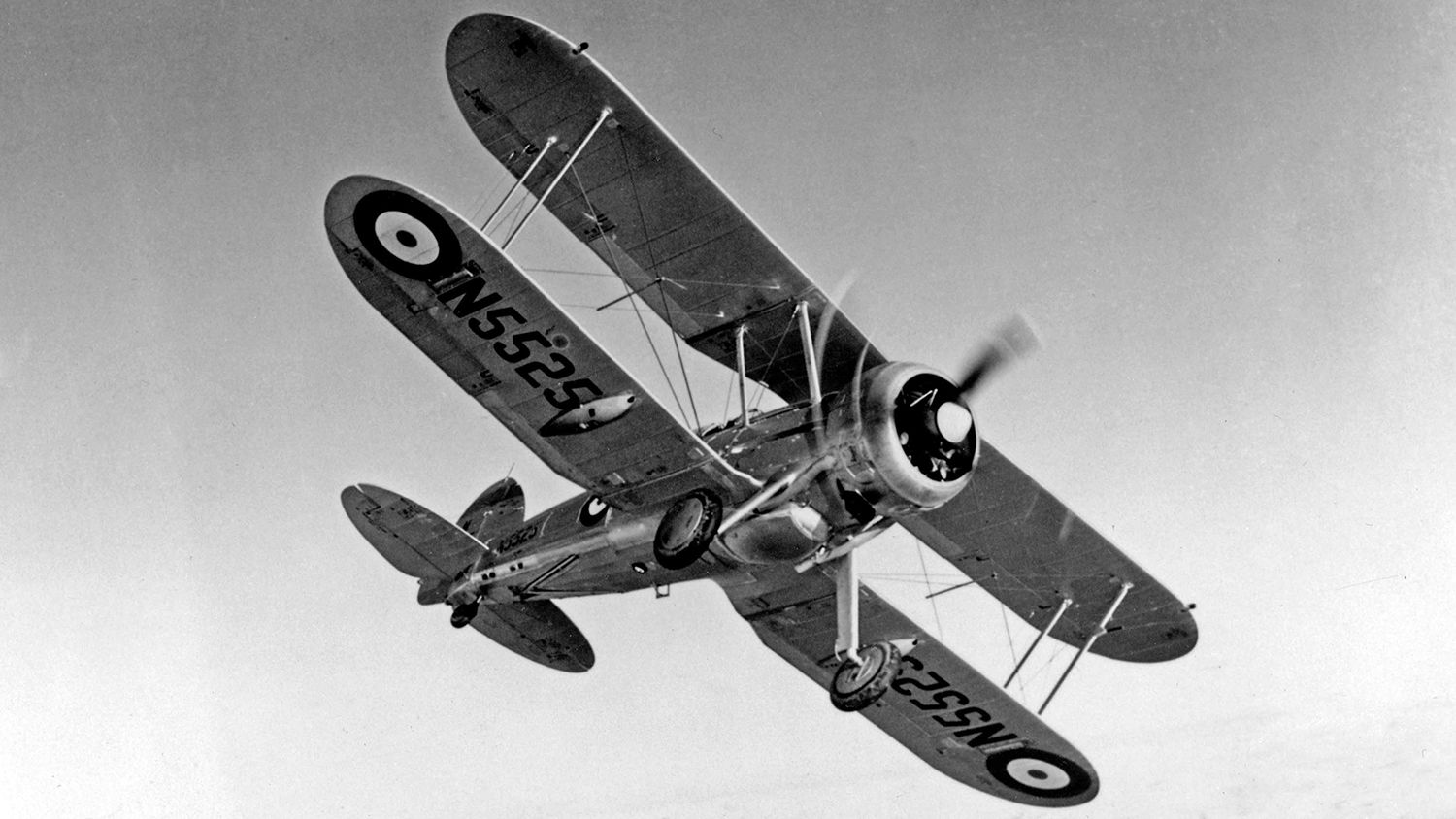

Despite being lauded as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier,” Malta was a low priority for aircraft assignments. Only a handful of fighters were based there at the outbreak of war, with a few others awaiting assembly. The aircraft were Gloucester Sea Gladiators, a navalised variant of the Gladiator fighter which was introduced in 1937—the same year the Luftwaffe received the rather more impressive Messerschmitt Bf-109.

Although it had a glazed cockpit and some modern features, the Gladiator belonged to an earlier era. Built of wood and canvas, Gladiators often caught fire and their armament of four .303-caliber machine guns was adequate, at best. Its only advantage was maneuverability. The exact number of aircraft available at any given time is difficult to determine, as some were cannibalized for spare parts and others repaired, while replacements were put together from those in storage. There is a popular belief that at one point there were just three or four airworthy Gladiators. In reality, the number was probably greater than that—but not much.

In addition to land-based air defenses and a handful of obsolete fighters, Malta was protected by two gunboats and the Erebus-class monitor HMS Terror. Commissioned in 1916, HMS Terror mounted two 15-inch guns and had received a considerable antiaircraft armament upgrade during a 1939 refit. These vessels were of questionable value against a major naval attack but entirely sufficient to make an amphibious assault unviable.

The Italian offensive against Malta opened in June 1940 with air attacks against the island. On the first day of the assault, no Allied planes could get into the air as the runways were still under construction. After this it became possible to get Gladiators in the air, though at times the island’s interception capability was limited to a single fighter.

Even at this juncture, Malta had the potential to strike at Axis shipping by acting as a base for submarines. This capability was expanded by the arrival of a force of Fairey Swordfish of the Fleet Air Arm. The Swordfish was known as the “stringbag,” not in a derogatory way but for its ability to handle almost any task in the same way a string bag could accommodate odd-shaped objects. Capable of carrying bombs, torpedoes or depth charges, the Swordfish was obsolete but still effective. Raids from Malta sank an Italian destroyer and caused damage to the port at Augusta.

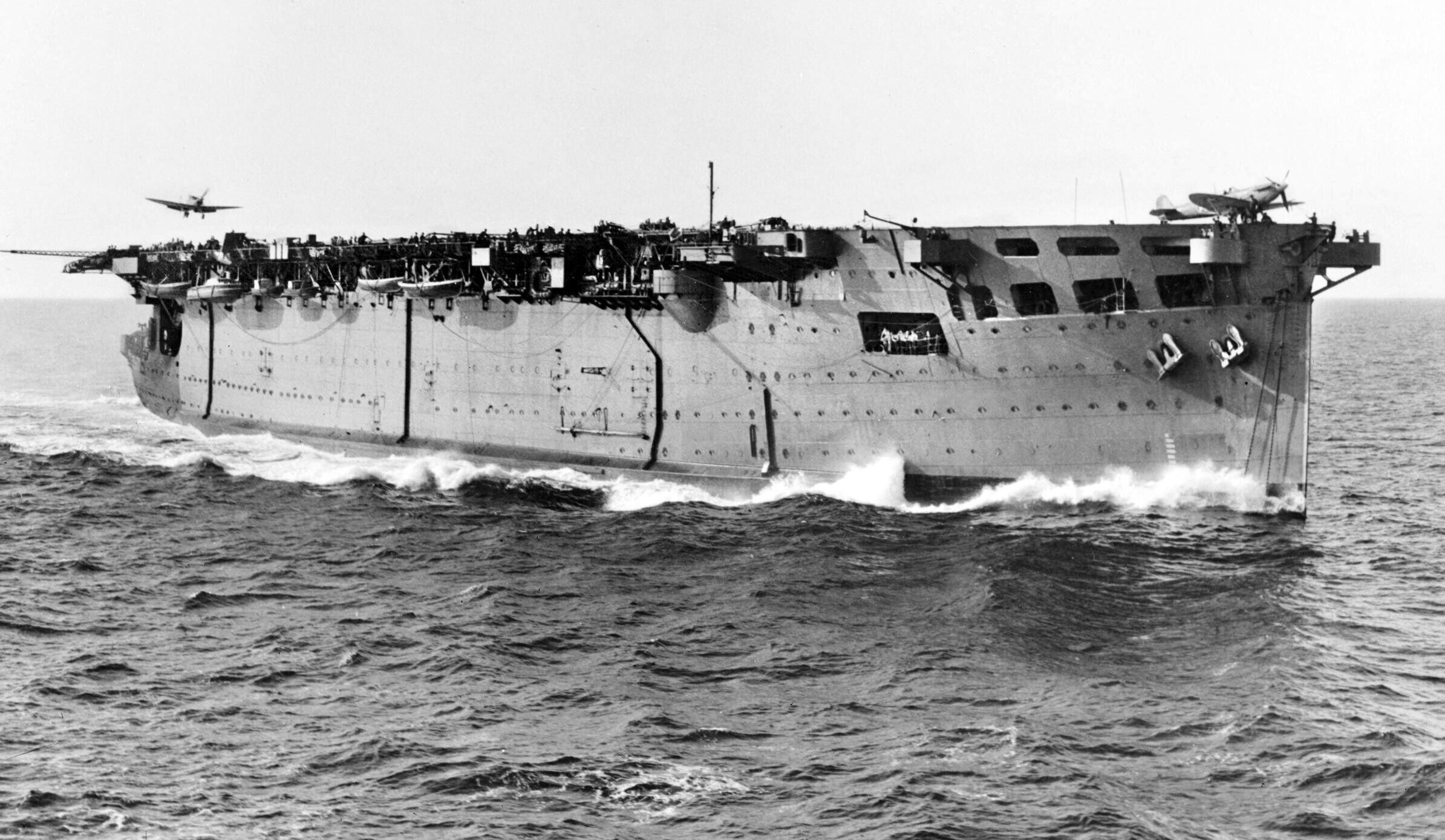

Reinforcement continued in July, with the arrival of 12 Hawker Hurricane fighters delivered by the carrier HMS Argus. This was achieved by launching the aircraft off at the point where the ships needed to turn around to avoid the Italian fleet. A miscalculation could result in the fighters having too little fuel to reach the island and no alternative landing point. Multiple aircraft were lost during an attempted reinforcement in November 1940.

The fighters were effective to the point that some pilots reported Italian bombers discarding their ordnance and racing for home at the sight of a couple of Hurricanes, but turnover was high. With few spares available, aircraft had to be cannibalized to keep others flying, and losses were continuous. However, the defenders of Malta continued to exact a toll on the Italian air force. Malta had endured a great siege before, but this time she was besieged—and defended—from the sky.

The Italian Army’s campaign in North Africa was dependent on supplies shipped into Libya. These convoys were harassed by aircraft and submarines operating out of Malta, inflicting losses and tying down vessels as escorts. It was not possible to completely interdict the supply lines, but each sinking contributed to the defeat of the Italian Army.

In early July 1940, heavy units of both the British and Italian fleets were at sea. The Italian force was covering a supply convoy bound for Benghazi, Libya. This was the first large-scale resupply operation since the outbreak of war and was carrying urgently needed fuel, munitions, personnel, and armored vehicles. The escort consisted of destroyers and torpedo boats, with a cruiser group and a heavy force of battleships and cruisers nearby should they be required.

The British were protecting a supply convoy to Malta and one engaged in evacuating civilians. Their dispositions included a cruiser group, a single battleship and escorting destroyers, and a force of two battleships, an aircraft carrier and destroyers. While the convoys were the priority, the British commanders considered a clash with the Italian Navy to be desirable.

What became known as the “battle of Calabria” began on July 8. Detected by reconnaissance aircraft, the British force came under heavy but ineffective air attack as it maneuvered to get between the Italian fleet and its base at Taranto. The two fleets engaged the next day, resulting in an inconclusive encounter fought mostly at long ranges. Torpedo attacks by Swordfish aircraft flown off the carrier HMS Eagle proved ineffective, and Italian air attacks similarly failed to do much damage.

Although the battle of Calabria was inconclusive, both sides claimed victory. This was not unreasonable; the convoys got through and some damage was inflicted upon the enemy. With the strength of surface forces more or less equal and the Royal Navy operating from distant bases, the main maritime threat to Italian convoys was the force of submarines based in Malta. These inflicted losses but suffered accordingly.

Even when not at sea, the submarines were vulnerable. Plans to construct bombproof pens for the submarine force were scrapped before the war. The only option was to try to hide them by submerging when an air attack began. This was largely successful, but for the wrong reasons. A downed enemy pilot was asked why the Axis air forces were not attempting to bomb the submarines, to which he replied that pilots were ordered to ignore them. So badly hidden were the boats that the enemy assumed they were decoys. A more serious threat to the submarine force was naval mines, liberally laid by the Italian forces around Malta to make resupply difficult and as barriers around the naval supply lines.

Despite these hazards the submarine force, designated the Tenth Submarine Flotilla, pressured the Italian supply lines as best it could. The difficulty of supplying Malta meant that sufficient torpedoes were never available, so commanders were ordered to pass up all but the most lucrative targets such as tankers or major warships. Had they possessed sufficient ordnance, the submariners might have inflicted much greater losses on enemy shipping, but instead they were placed in a vulnerable position without gaining full advantage from their forward deployment.

Despite prewar planning for an invasion of Malta, it was clear that the Italian forces would not be able to capture the island by direct assault. Air attacks were failing to wear down the defenders quickly enough, and accusations were made that Italian aviators were not sufficiently aggressive. From January 1941, Luftwaffe squadrons began arriving in Sicily and launching attacks against Malta.

Many of the aircraft were Junkers Ju-87 Stukas—excellent dive bombers, but slow and vulnerable to interception. Allied pilots soon learned that a Stuka was an easy target while making its dive to attack. Hurricane pilots would wait above the enemy formations, breaking off one by one to chase a Stuka in its dive. Closing fast from behind against a predictable target, kills were so common that this kind of attack became known as a “Stuka Party.” To be shot down by a Ju-87 rear gunner under these circumstances was a source of great embarrassment.

Having increased the pressure on Malta, the Luftwaffe squadrons based in Sicily were given a wider role revolving around attacks on Allied shipping. Capital ships were prime targets, and especially aircraft carriers. Originally seen as a support element for the battleships, the effectiveness of carriers was now being fully appreciated. In November 1940, Swordfish from HMS Illustrious entered Taranto harbor and inflicted heavy damage on the battleships of the Italian Navy, not only putting ships out of action for a time but prompting a move to the greater security of Naples.

The Taranto raid tipped the balance of power in the Mediterranean for a time, and the change of home base impeded Italian naval efficiency. This did not prevent a successful sortie on November 17, just five days after the Taranto raid. The intent was to prevent reinforcement of Malta’s air strength, and in that it succeeded. The British force turned back to Gibraltar after launching its aircraft, most of which had insufficient fuel for the transit. Another reinforcement operation was launched in late November, and once again the Italian Navy sortied to intercept it. The result was an inconclusive naval engagement off Cape Spartivento on November 27.

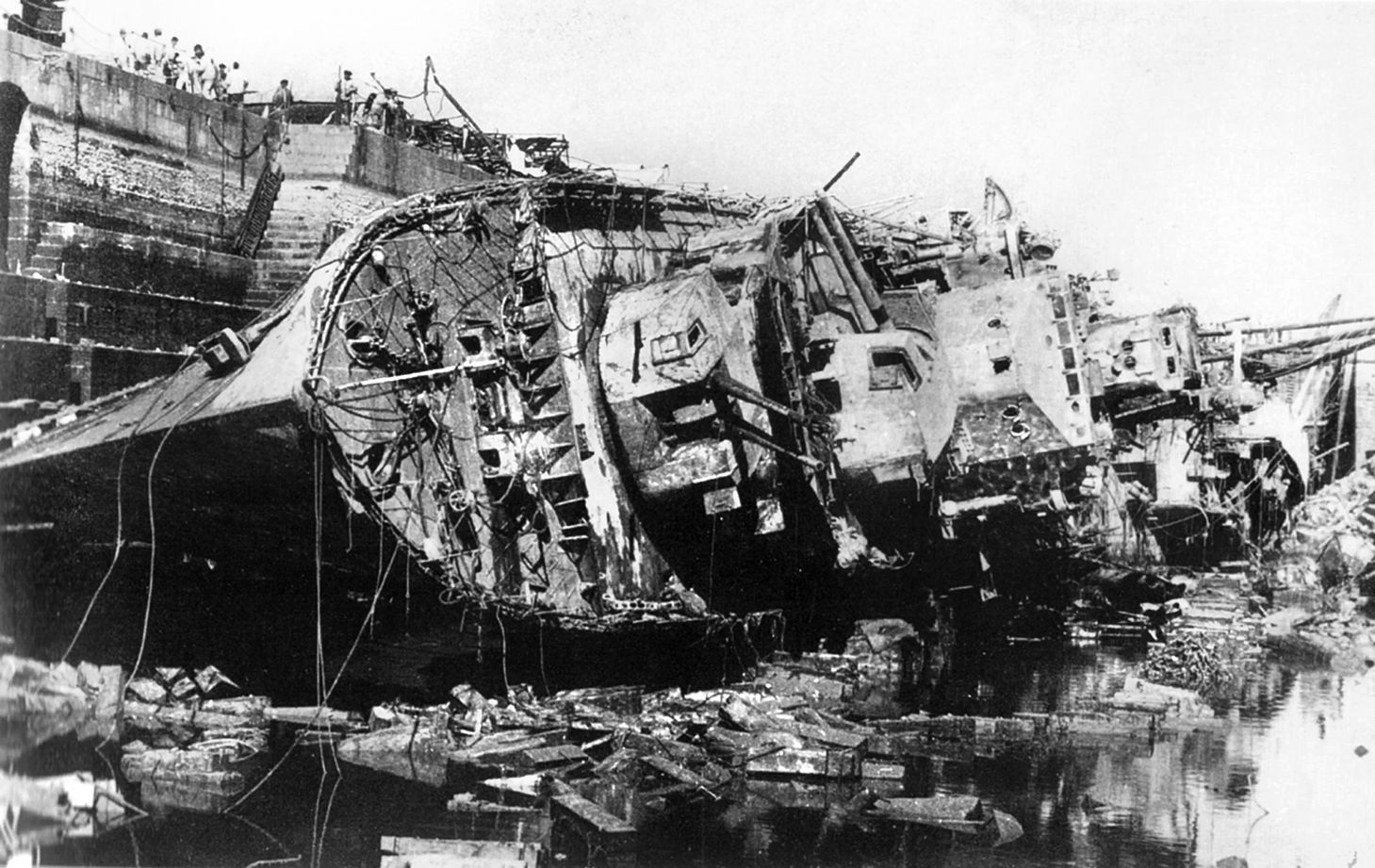

The Allied decision to send troops to Greece, starting in March 1941, was made necessary by the German move to assist Italy in conquering the region. Italy had been at war with Greece since October 1940, but without German intervention the campaign had stalled. Moving troops from North Africa weakened the Allied position there and exposed the escorting naval assets to attack. On January 10, 1941, while providing air cover for the troop convoys, HMS Illustrious was attacked by Ju-87s. At the time her fighters were out of position and, severely damaged, the carrier headed for Malta to make repairs.

There was really no alternative for Illustrious than to head for Malta. With her steering out of action, she could only be guided using her engines. However, Malta was anything but a safe port. While repairs were being made, the carrier was a large and static target, suffering further damage from air raids while in dock. Illustrious was able to escape from Malta on January 23, going first to Alexandria and ultimately to the United States for major repairs.

In late March, the British carriers achieved a measure of revenge when aircraft from HMS Formidable temporarily immobilized the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto and crippled the cruiser Pola off Cape Matapan. This engagement, the Battle of Cape Matapan, came about as a result of an Italian sortie to intercept Allied troop convoys to Greece. While the heavy units of the Italian force were able to leave the battle area, Pola and a force sent to assist her were caught after dark at point-blank range by a British force that had trained extensively for night actions. The Italian Navy lost three cruisers and two destroyers, inflicting virtually no damage in return.

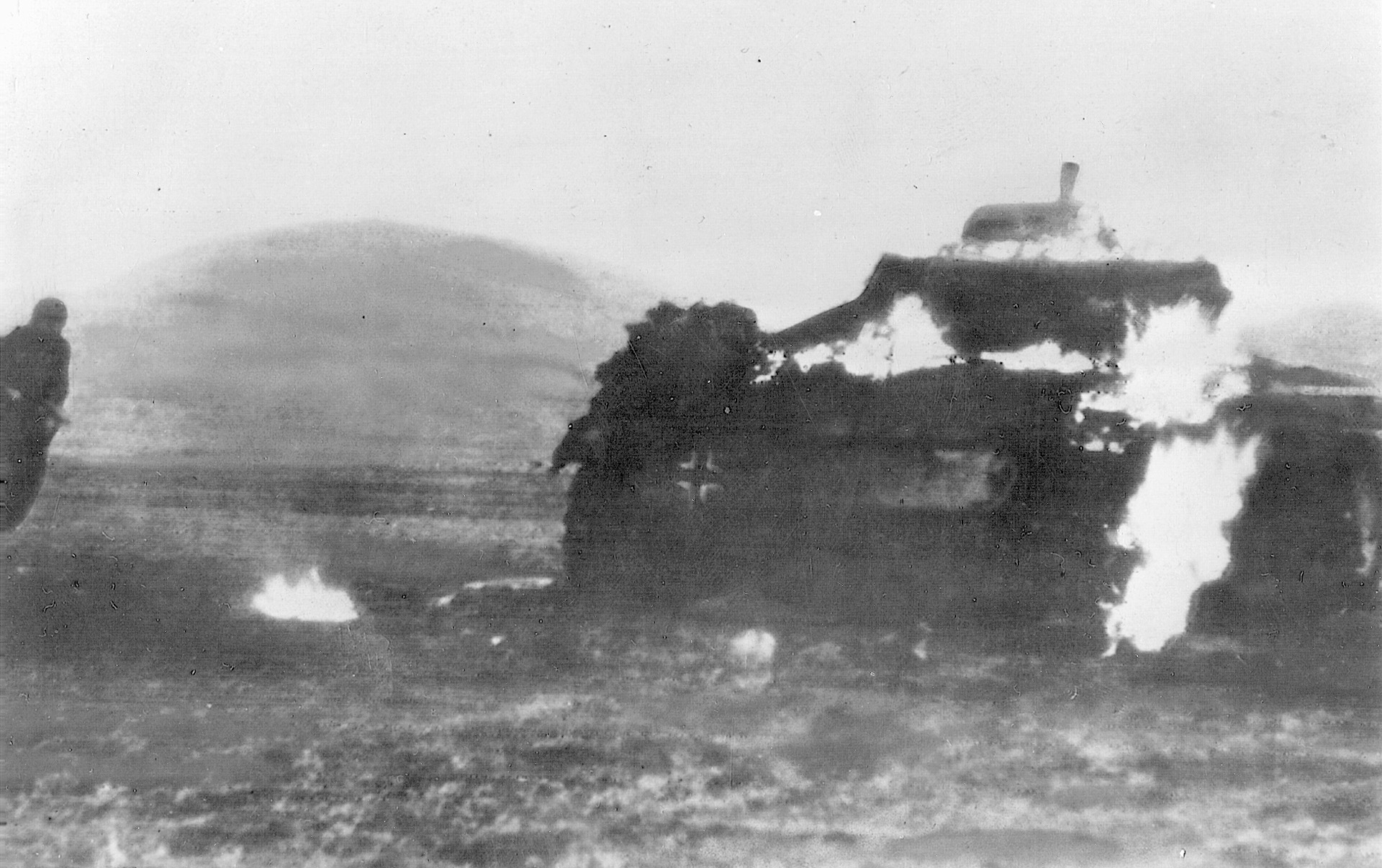

While the British were weakening their forces in North Africa in order to assist Greece, the Axis presence in North Africa was greatly strengthened. Days after the Italian defeat at El Agheila, German troops began landing in Libya. After a period spent acclimating and reorganizing, this new “Afrika Korps” launched its first offensive in March 1941. German tanks were vastly more potent than their Italian counterparts and, more importantly, they were well handled. Close cooperation between infantry and armor resulted in defeat for the less well coordinated British forces, compelling them to retreat.

Logistics played a huge part in the desert war. Just supplying enough water to drink and fill vehicle radiators required fleets of trucks, which in turn needed fuel and supplies for their crews. The supply line could be shortened by possession of a port close to the battle area, and to this end Tobruk in Libya was a major Axis objective. Although the Allies were driven back past Tobruk, it remained in the hands of Australian troops, forcing the Afrika Korps to operate at the end of a long supply line.

Meanwhile, losses suffered at the hands of Allied fighters over Malta prompted the deployment of German fighter squadrons. Not only were the pilots experienced and well-trained, their BF-109 fighters were superior in performance to the Hurricanes used by the Allies. Losses quickly mounted, with damaged aircraft cannibalized to keep a rapidly depleting force operational. More Hurricanes were brought in, but the Axis powers enjoyed near-complete air superiority over Malta.

The presence of an effective Axis fighter force made it impossible to launch air strikes from the island and reduced the defenders’ ability to inflict losses on raiding aircraft. Malta was forced onto the defensive, fighting for survival rather than acting as a base to interfere with enemy convoy operations.

Despite these hazards, a destroyer force was assembled and based out of Malta. This exposed ships to air attack when in port but allowed some pressure to be put on the Axis convoys heading to Africa. This lasted until May, when the force was reassigned to the battle for Crete. During this time, Axis air power dominated the central Mediterranean, allowing their convoys to go through almost unopposed and making the area untenable for Allied vessels. British Reinforcement attempts brought in a few extra planes now and then, but not nearly enough to fend off the constant bombing raids.

This desperate situation continued even after German fighter squadrons were transferred to the new Eastern Front in June 1941. The air warfare capability of Malta, though determined, was feeble, and the Italian Air Force continued to pound the island on a daily basis. It was not enough for the island to endure; with the Afrika Korps threatening to drive into Egypt, Malta had to find a way to mount an offensive against the Axis supply convoys.

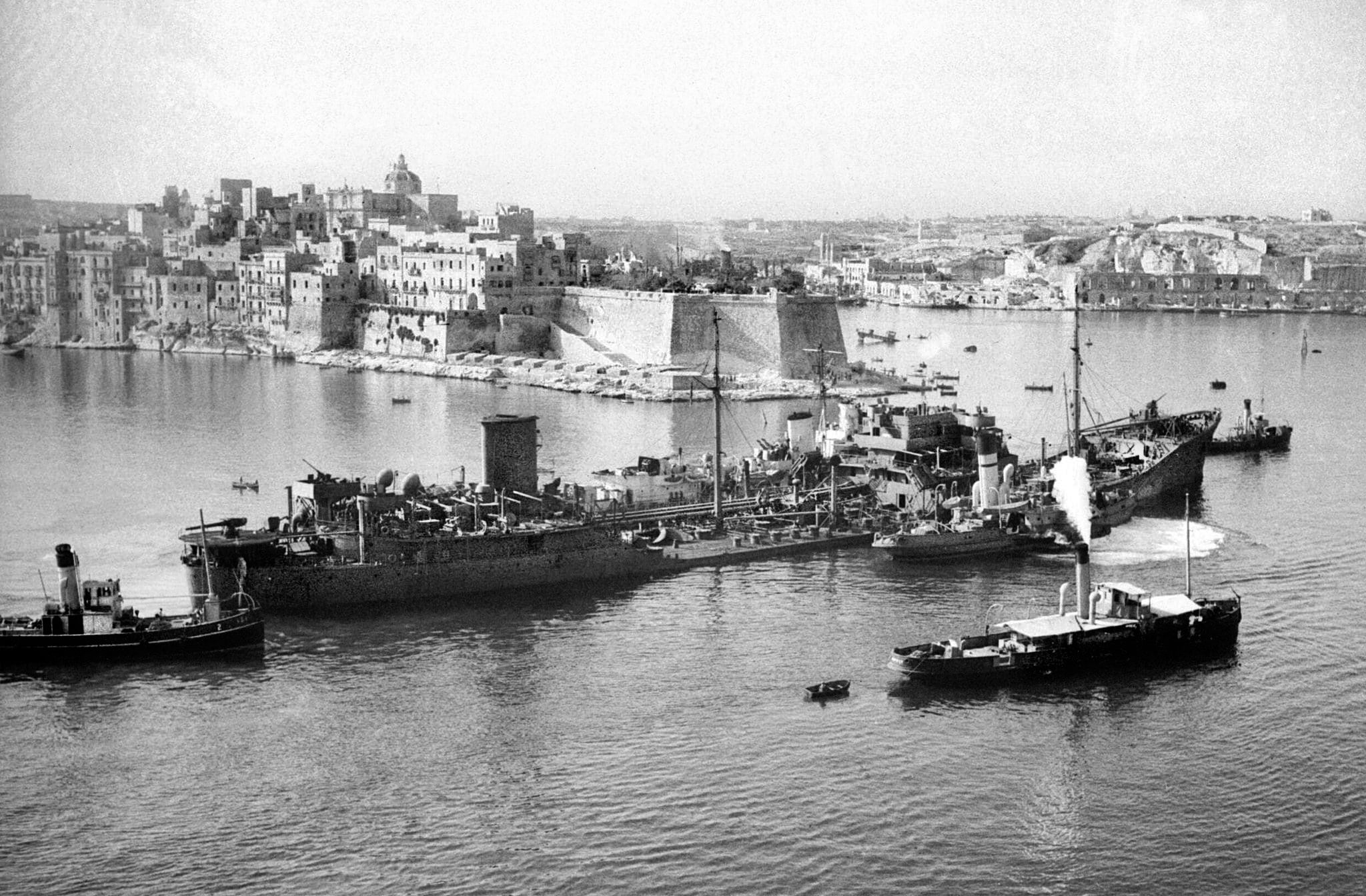

The only solution was major reinforcement of Malta’s air forces, and the provision of large quantities of spares and supplies. This began in June 1941, with convoy GM1 driving through from Gibraltar to Malta. Despite attacks by aircraft, torpedo boats, and submarines the convoy reached Grand Harbour in Malta, delivering the first of several shipments of supplies.

Malta’s strength increased through the late summer, to the point where a bomber force was once again able to operate from the island. Defenses and aircraft maintenance capabilities were improved, the latter greatly increasing the efficiency of the air units operating from the island—making it a possible staging area for supplies headed for Egypt.

This activity was strongly opposed from the air and at sea. In late July an attack was made by Italian small-boat raiders, which was repulsed by coastal artillery with heavy losses. Despite such efforts Malta grew in strength. Forces based there had a profound effect on the flow of supplies into North Africa. What got ashore had then to be conveyed hundreds of miles to the Afrika Korps, greatly limiting its capacity for offensive operations against Tobruk.

Allied attempts to relieve Tobruk were unsuccessful during the summer, but in November 1941 a renewed Allied drive struck the Afrika Korps as it was making another attempt to take the port. The deciding factor here was supply levels. Almost out of fuel after days of heavy fighting, the Afrika Korps was forced to retreat with just a handful of tanks remaining operational.

The transfer of German fighter squadrons to the Eastern Front had permitted Allied pilots to gain control of the skies around Malta, but in January 1942 it seemed that the Soviet Union might already be defeated. Powerful Luftwaffe air groups returned to Sicily, inflicting heavy casualties on Allied strikes out of Malta and on the island’s fighter force.

The outmatched Hurricane pilots petitioned for Spitfires, which could meet the Bf-109 on equal terms, and from March the first aircraft began to arrive. Once again the method of delivery was to fly the aircraft off a carrier at the closest point of approach. While this did away with the necessity of fighting a convoy all the way through and risking contact with the extensive minefields around Malta, it was slow and inefficient. Nevertheless, the arrival of Spitfires enabled Allied pilots to defend the island even if little power could be projected from it.

Luftwaffe control of the air cleared the way for supply convoys into Libya, enabling German forces there to regain their strength. Having been driven all the way back to El Agheila, the Afrika Korps remained on the defensive until January 1942. By this time it was the Allies who were suffering logistics problems, forcing them to fall back on a defensive line running through Gazala. This held up the German advance until May 1942, when the line was breached by a new offensive. Tobruk was taken, greatly shortening the Axis supply line, and the Allies were driven all the way back to El Alamein just inside the Egyptian frontier.

It was here that the Afrika Korps launched its final major offensive in North Africa. Despite a critical shortage of fuel caused by Allied attacks on the convoys and supply lines, an outflanking movement was planned to take place near Alam el Halfa. Such assaults were the trademark of the German armored forces but relied on sufficient fuel. Allied reinforcements would soon make the situation untenable for the Axis forces, so the decision was made to launch the attack and hope a tanker got through in time.

As the battle raged from the end of August until September 5, Allied air power interdicted the Axis supply routes. Ships carrying fuel were sunk, crippling the armored forces, and after days of hard fighting the offensive was repulsed. An immediate Allied counterattack might have been a disaster, running into prepared anti-tank positions as others had in the past, but this time the Allies were content to wait for reinforcements and prepare a decisive blow.

The Axis leaders had considered an invasion of Malta even before the war, and various plans were put forward for an invasion using paratroopers as well as an amphibious landing. Such an assault required air superiority, which the Axis powers currently enjoyed. However, the arrival of more Spitfires gradually tipped the balance.

Although the Allied “club runs,” as the delivery operations were known, tied up aircraft carriers and their escorts, they were essential to thwarting the proposed invasion. As Axis aircraft losses mounted it became apparent that Malta could not be successfully assaulted. Its ability to interfere with Axis supply convoys could be suppressed by continued air attacks, but the island’s powerful fighter defenses were inflicting a fearful toll in return.

Malta was entirely dependent on supplies brought in by sea. Submarines could bring a little cargo, but for the fighters to remain operational it was necessary to push large convoys through to the island. By late summer 1942, the situation was desperate. Even basics such as food and clothing were in short supply, while lack of ammunition and fuel crippled the island’s defense.

To restore the situation, the Allies launched two convoys—one from Gibraltar and one from Egypt—under heavy naval escort. The latter was forced to turn back after running low on ammunition, but part of the Gibraltar convoy reached Malta. Both sides lost heavily in a series of engagements along the way.

A renewed effort to resupply Malta was made in August. Codenamed “Operation Pedestal,” this was one of the pivotal moments of the war. Malta’s fuel supplies were all but exhausted, and without air cover the island could not be defended. Everything depended on getting a tanker through to Malta, but resistance was heavy. The Allies lost HMS Eagle along with a cruiser, three destroyers, and most of the merchant ships.

The convoy became dispersed, making defense even more of a problem than it had been. During the worst of the voyage, one destroyer captain reportedly said that so long as there was anything afloat he would put his ship beside it and fight through to Malta. This officer was a survivor of the Convoy PQ17 disaster far to the north, and made good on his word. Almost 24 hours after the rest of the convoy, the heavily damaged tanker Ohio was towed into Malta by three destroyers. The fuel she carried revitalized the defense of the island.

Finally able to operate fighters in strength, the defenders of Malta changed their tactics. More aggressive interceptions using larger forces inflicted heavy losses on the Axis air raids. Among other results, this reduced the pressure on the island’s submarine force. For some time its base had been a target for heavy attack, greatly hampering the force’s offensive capability, but now it became possible to operate more freely. Combined with air attacks on shipping, this once again impacted the Axis convoys into North Africa.

When the Axis advance had stalled near El Alamein, the Allies did not launch an immediate counter-offensive. Instead, they concentrated on building up strength for an overwhelming assault. This came in late October 1942, finally breaking the Axis defense 10 days later. Another rearguard action along the coastal strip followed, reaching El Agheila in late November. There would be no further Axis success in North Africa.

Early in 1943, the British pushed into Tunisia, gradually driving the Afrika Korps north. American troops had also landed in North Africa, and despite stubborn resistance the Allies reached Tunis in May, 1943. Some units were evacuated, but more than 250,000 Axis troops were taken prisoner. In addition to this enormous loss of manpower, the Axis also lost its foothold in Africa. No further threat to Egypt existed, and the way was open for a push north across the Mediterranean.

Allied advances in North Africa drew Luftwaffe elements away from Malta to support the beleaguered Afrika Korps. Indeed, a convoy in late November suffered only minor losses, and subsequent convoys met little resistance. Malta was now a well-supplied, fortified base from which to dominate the central Mediterranean.

Ultimately, Malta dictated the course of the war in the Mediterranean and North Africa. Strong forces there choked the Axis supply lines and crippled the land campaigns, while heavy pressure on Malta forced the Allies to risk irreplaceable naval assets under extremely hostile skies. Forces involved in these battles were unavailable for use elsewhere, perhaps impacting campaigns in other theaters of war.

It is interesting to speculate what the Allied carriers tied up on “club runs” might have achieved, or how the German squadrons in Sicily might have influenced another campaign. What is clear is that Malta’s pressure on Axis supply convoys was instrumental in the defeat of the Afrika Korps and future Allied offensive operations in the Mediterranean theater.

Martin J. Dougherty hails from northeast England. In addition to writing many books and articles, he is an accomplished swordsman.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments