By Lieutenant Colonel Michael F. Trivet

As the months of 1945 passed at an agonizingly slow pace, Allied forces in the Pacific struggled unwaveringly toward Japan. Expectedly, during the summer of 1945, Allied forces led by the United States faced the prospect of invading the Japanese home islands. The overarching plan for the invasion and occupation of Japan was code-named Operation Downfall. Kyushu, the southernmost of the four home islands, would be the first attacked and occupied. Planning for the invasion and occupation of Kyushu, code-named Operation Olympic, began even as the fighting on Okinawa raged in the spring of that year.

After the difficult victory on Okinawa, American-led forces faced the dreadful prospect of continuing the fight on the home islands of Japan in which tens of millions of Japanese would wage conventional then unconventional warfare with no foreseeable end. As they demonstrated on Guam, Saipan, Tinian, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, in the Philippines, and on numerous other islands, the Japanese intended to fight to the death. Not only was surrender by Japanese soldiers forbidden, so too was surrender by Japanese civilians. On Saipan, Japanese civilians held out until there was no hope in their view. Instead of surrendering or being captured, many of these civilians, including mothers holding their infants, leaped from rock cliffs to their deaths.

Consequently, Allied forces faced brutal fighting in the pending conquest of Japan. Allied planners estimated that an invasion and occupation of Kyushu Island alone would require 766,700 ground forces. Allied casualties were expected to reach 105,000 just to seize the southern part of Kyushu, more than double the casualties sustained fighting on Okinawa.

Operation Blacklist

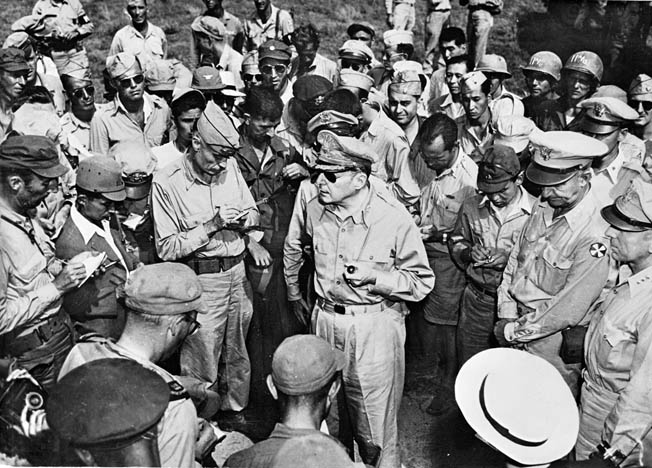

Even before the issuance of Operation Olympic and before he knew of the existence and intended use of the atomic bombs, General MacArthur directed his staff to begin developing Operation Blacklist in May 1945, to address the possibility of surrender by or complete collapse of the Japanese government. Assumptions for Olympic, including expected casualty ratios, led Allied leaders to seek the unconditional surrender of Japan.

The Potsdam Declaration, requiring unconditional surrender, was issued in July 1945. However, the Japanese did not provide a timely response. Consequently, as late as August 14, Allied military leaders did not know which operation, Olympic or Blacklist, they would execute. Fortunately for all parties, the Japanese surrendered following the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The devastation of these two cities and the fear of future atomic bomb attacks, however, did not generate any substantial attitude for surrender within the Japanese military leadership or among the general population. “The Japanese Army announced that the Nagasaki bomb was not formidable and that the military had ‘countermeasures.’ The high command … did not believe the war was lost.”

Consequently, the key to Japan’s surrender was the position of and statements from Emperor Hirohito in early August 1945. In an unusual speech during the Imperial Conference of Japanese leaders at 2 am on August 10, 1945—unique that he spoke at all but even more astounding that he took such a strong position rebuking the military leaders present— Hirohito voiced his “divine” decision: “After serious consideration of conditions facing Japan both at home and abroad, I have concluded that to continue this war can mean only destruction for the homeland and more bloodshed and cruelty in the world…. I cannot bear to have my innocent people suffer further. Ending the war is the only way to restore world peace and relieve the nation from the terrible suffering it is undergoing.”

Initially, the military leadership opposed the terms of surrender, but after much internal wrangling and confusion, the Japanese government, on August 14, 1945, officially announced its surrender and acceptance of the terms outlined in the Potsdam Declaration. The most important point for the Japanese was the continuation and protection of Emperor Hirohito. The Japanese conceded everything else required in the Potsdam Declaration. General MacArthur was named Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), and the various parties met on the morning of September 2 for the formal surrender ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Because the Japanese achieved their primary goal of keeping the emperor in his position and continuing the imperial system, albeit with much reduced authority, the Japanese did not unconditionally surrender. Nonetheless, it would be Operation Blacklist.

The Art of Counterinsurgency Warfare

Insurgencies are not necessarily small wars, as evidenced by the protracted Chinese communist insurgency against the nationalists and the potential for insurrection in Japan. Additionally, insurgencies often develop in response to occupations by foreign powers, such as those in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iraq, Malaya, Palestine, Spain, Vietnam, and numerous others. During World War II, some Allied leaders, particularly MacArthur, understood all of this from education, experience, and events preceding the war, including lessons from such historical conflicts as the American Revolution, Boer War, American Indian Wars, and the Philippine Insurrection. Consequently, the announcement and formal surrender by the Japanese did little to assuage U.S. military concerns regarding the occupation and demilitarization of Japan.

Although military occupations of various countries, regions, or periods may have few similarities, the manner in which occupying forces conduct themselves and the methods they use always influence the nature and outcome of an occupation. Related to this, over 2,200 years ago, Sun Tzu wrote, “To win a hundred victories in a hundred battles is not the highest excellence; the highest excellence is to subdue the enemy’s army without fighting at all.” He also wrote, “He who knows the enemy and himself will never in a hundred battles be at risk.”

These were key premises of General MacArthur’s plan in successfully occupying Japan in 1945, which was the crowning achievement of the Allied forces in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Unfortunately, to the detriment of many, this model of counterinsurgency and occupation is often overlooked by military and political leaders and historians because there were no armed battles to discuss or analyze. It was simply not sensational in terms of armed conflict, maneuvering, and military tactics. Yet, when viewed in terms of countering the largest potential insurgency ever faced by an occupying power, incontrovertible actions and principles become apparent.

An Empire Resistant to Capitulation

In immediate postwar Japan significant concern existed over questions of whether the entire Japanese military would accept surrender and whether the general population would comply with the terms of surrender. Should occupation forces face the prospect of the entire population of Japan fighting against them, they would need millions of troops to defeat and pacify the Japanese people. MacArthur knew too well as he explained, “History clearly showed that no modern military occupation of a conquered nation had been a success.”

In 1945, the population of Japan was approximately 80 million. The Japanese National Volunteer Force consisted of 25 million nonmilitary men, women, and children, ready to support their military, defend their homeland, and fight with whatever means they could muster. Before the occupation in 1945, SCAP headquarters estimated that more than 1,700,000 former members of the Japanese military would have to be disarmed along with 3,200,000 civilian defense volunteers.

Even the Japanese leadership worried over its ability to get the surrender order disseminated with authority and credibility to not only the military but the entire population. When informed that the first occupation troops would arrive on August 23, historian Samuel Eliot Morison writes, “the Japanese asked for more time, stating the problem of controlling their own armed forces and pleading that delay would enable them to prevent regrettable incidents.” The Japanese military was so strongly opposed to surrender that “hotheads in the Japanese Army Air Force threatened to shoot down any surrender mission that took off” from Japan to meet with the Allies.

The Goals of Operation Blacklist

With deep concern over the enormous magnitude of tasks regarding the occupation of the Japanese home islands, American forces executed Operation Blacklist. Under Blacklist, Morison wrote, “the initial, primary missions of the Occupation forces were set out as being the disarmament of the Japanese armed forces and the establishment of control of communications. MacArthur fully intended to use the Emperor and other Japanese leaders in executing every aspect of the occupation [being] thoroughly familiar with Japanese administration.” He outlined and prioritized the following goals of the occupation:

(1) Destroy the military power. (2) Punish war criminals. (3) Build the structure of representative government. (4) Modernize the constitution. (5) Hold free elections. (6) Enfranchise the women. (7) Release the political prisoners. (8) Liberate the farmers. (9) Establish a free labor movement. (10) Encourage a free economy. (11) Abolish police oppression. (12) Develop a free and responsible press. (13) Liberalize education. (14) Decentralize the political power. (15) Separate church and state.

Delegation of authority from SCAP to tactical-level units was an essential aspect of the occupation contributing to its success. Specifically related to disarmament, countering opposition, rebellions, and potential insurgencies, MacArthur through Blacklist delegated the following “Special Tasks” to Army commanders, all of which they accomplished in an exceptionally professional manner under extraordinary circumstances:

a. Destruction of hostile elements which might oppose by military action the imposition of surrender terms upon the Japanese.

b. Disarmament and demobilization of Japanese armed forces and their auxiliaries as rapidly as the situation would permit. Establishment of control of military resources insofar as would be practicable with the means available.

c. Control of the principal routes of coast-wide communication, in coordination with naval elements as arranged with the appropriate naval commander.

d. Institution of military government, if required, and the insurance that law and order would be maintained among the civilian population. Facilitation of peaceful commerce, particularly that which would contribute to the subsistence, clothing and shelter of the population….

f. The securing and safeguarding of intelligence information of value to the United States and Allied Nations. Arrangement with the U.S. Navy for mutual interchange and unrestricted access by each Service to matters of interest thereto.

g. Suppression of activities of individuals and organizations inimical to the operations of the Occupation forces. Apprehension of war criminals, as directed….

i. Preparation for the imposition of terms of surrender beyond immediate military requirements.

j. Preparation for the extension of control over the Japanese as required to implement policies for postwar occupation and government, when prescribed.

k. Preparation for the transfer of responsibilities to agencies of the post-war governments and armies of occupation, when established.

Mobilizing the Japanese Population

The key method in which U.S. occupation forces carried out these “Special Tasks” was by employing the Japanese themselves to do the majority of the work. MacArthur and his staff never intended for American troops to actually conduct all of the specific work necessary for accomplishing the numerous goals of the occupation.

It was emphasized that in view of the limited forces that would have to occupy a country of roughly 80 million, Army commanders would make all possible use of Japanese demobilized forces … and would take all steps to insure that public servants, such as the civil police, railway workers, communication workers, utilities operators and public health officials, not only remained at their tasks but intensified their efforts to ensure a continuation of all functions under what was certain to be a period of great stress.

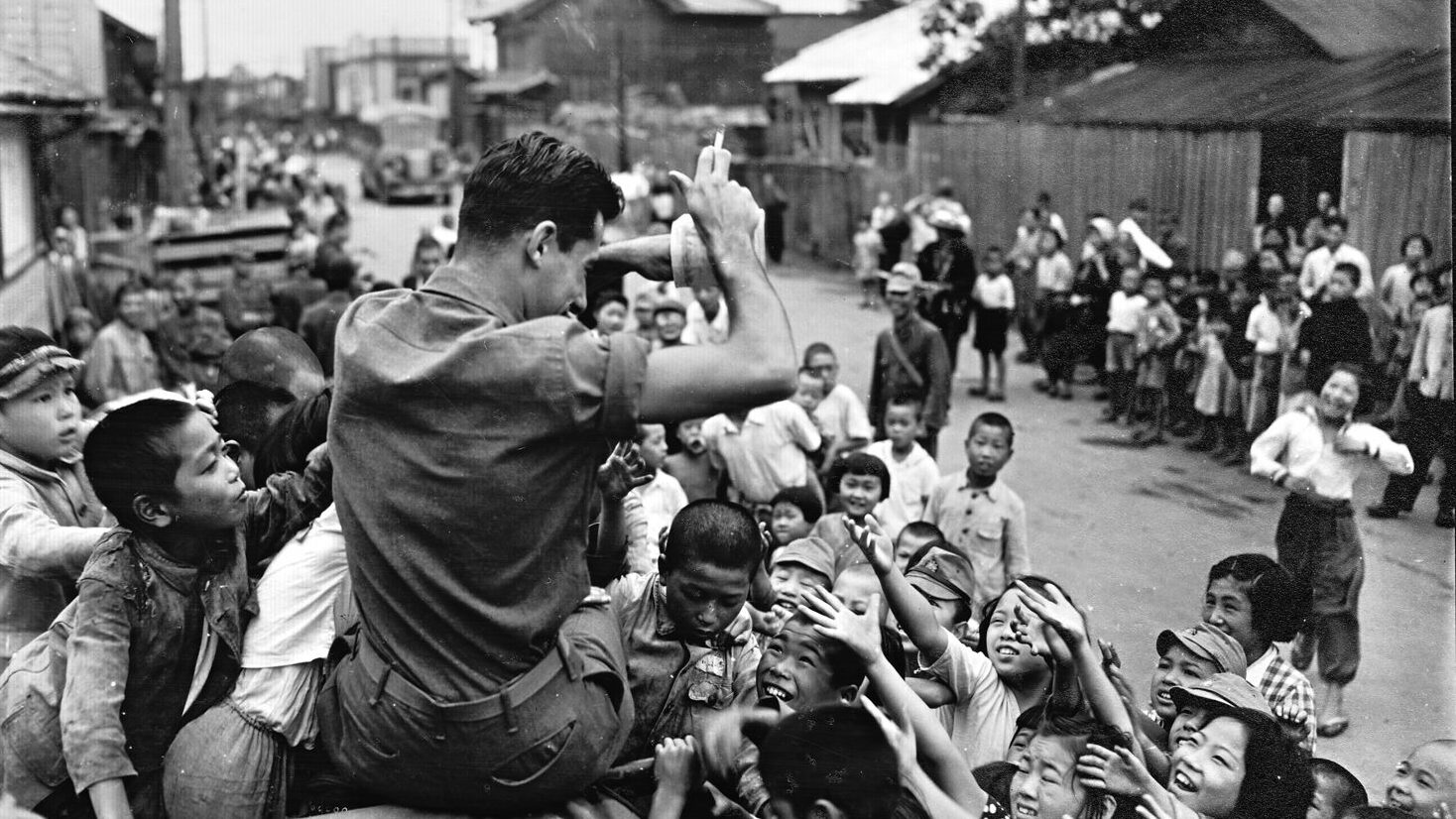

MacArthur later wrote that he cautioned his “troops from the start that by their conduct our own country would be judged in world opinion, that success or failure of the occupation could well rest upon their poise and self-restraint.” These methods were and remain fundamental to any successful counterinsurgency or occupation. He added that the Japanese would “shoulder the chief administrative and operational burden of disarmament and demobilization.” Unlike most other counterinsurgencies, this aspect of Operation Blacklist was “designed to avoid possible incidents which might result in a renewed conflict; no seizures or disarmaments were to be made by Allied personnel.”

Directive No. 1

Addressing the wartime political, military, and police leadership of Japan, SCAP issued Directive No. 1, on September 2, 1945, the day of the formal surrender. Directive No. 1 ordered “the Imperial General Headquarters to begin to demobilize all Japanese armed forces, and eleven days later the Imperial General Headquarters itself was abolished. The arrest of war criminal suspects [was to] begin.”

Just two and a half years following the surrender, approximately 5,700 war criminals were tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which found 920 of them guilty. Many of the guilty were hanged. Around 200,000 ultranationalists were purged out of public offices. Shinto was discontinued as the state religion. Large companies were broken up. Land reform was initiated, and the civil service was reconstituted.

Following SCAP instructions and priorities, primarily Japanese forces under U.S. military supervision destroyed over 11,000 aircraft, more than 1.2 million rifles and carbines, almost 190,000 artillery pieces, and approximately 1.2 million tons of ammunition. Additionally, hundreds of naval vessels and other equipment and weapons were destroyed. At least 135 naval vessels were delivered to the Allies for their use. The most common method of destroying or disposing of explosives and ammunition was dumping at sea. Amazingly, in less than three years SCAP implemented and oversaw all of these actions and those outlined earlier, affecting a population of 80 million with just over 200,000 troops.

Hirohito Keeps His Throne

The single most significant issue that would certainly have initiated a massive insurgency against the occupation forces if mishandled was the treatment of Emperor Hirohito. In the aftermath of the war against Japan, some Allies, principally the British and Soviets, wanted to prosecute Emperor Hirohito as a war criminal. MacArthur wisely and successfully fought against such imprudent and selfish ideas, angering many in the process. He knew that prosecuting Hirohito, the divine authority for all Japanese, would turn the entire population against the occupying forces, resulting in the largest insurgency against an occupying force in history. In addressing the issue of prosecuting the emperor for war crimes, author Edward Drea asserted, MacArthur “warned Washington in 1946 that if the emperor were tried as a war criminal, he’d need at least a million [additional] troops to garrison Japan to ensure law and order, and public security.”

MacArthur later said that he “believed that if the emperor were indicted, and perhaps hanged, as a war criminal, military government would have to be instituted throughout all Japan, and guerrilla warfare would probably break out.”

Law and order and public security, some of the most essential issues of counterinsurgency, were well understood by MacArthur and his staff. Accordingly, MacArthur’s decisions regarding Emperor Hirohito were twofold. First, he decided not to prosecute Hirohito, which for the most part alleviated the certainty of a massive insurgency. Second, he left Hirohito in his imperial position with somewhat more than just symbolic power. In the long term, this second action ensured tremendously important continuity of control and authority over the Japanese population.

Another important benefit of MacArthur’s actions regarding Hirohito was legitimacy, an indispensable aspect of successful counterinsurgency. In addition to leaving the emperor in place and successfully opposing his war crimes trial, MacArthur attained and increased the respect of the Japanese people and cemented his own legitimacy as supreme commander for the Allied powers, in effect, the legitimate ruler over Japan. This legitimacy was also conferred upon MacArthur by the emperor through public appearances, broadcasts, and speeches, all of which further suppressed any incipient insurgency within the Japanese population. All of these aspects of the occupation permitted the Japanese population to respect MacArthur and the occupation troops and to accept the postwar rules, regulations, and laws imposed by the Allies.

Allied Intelligence vs the JCP

The peaceful and tranquil transition of postwar Japan, especially when compared to occupations of other postwar nations, was the ultimate success of the occupation and was in large part due to the work of intelligence organizations. However, in addition to the possibilities of a general insurrection among the greater Japanese population, several factions or organizations posed problems for the governing forces. In preparation for and response to these groups, MacArthur wrote that the various intelligence organizations early on and consistently developed “intelligence information on every shade of public unrest—in the field of labor, in communist infiltration, and in movements of disillusioned, repatriated military personnel,” of whom there were millions.

To function effectively, military intelligence units had to change the methods in which they conducted activities, reorganizing and sharing information with all services, including Japanese police agencies. Intelligence on a conventional military foe no longer applied. Consequently, the SCAP G2 focused on “civil intelligence” and was divided, as MacArthur noted, into “four major components: Operations Branch, the 441st Counter Intelligence Corps, the Civil Censorship Detachment, and the Public Safety Division.” The most important adaptations took place within the realm of counterintelligence. “As the Occupation progressed, the duties of combating and controlling diverse elements, subversive or inimical to the objectives of the Occupation … were expanded immeasurably to cover every facet of the intelligence problem.”

MacArthur added, “The greatest single political group as a medium of potential trouble for the Occupation was the Japan Communist Party (JCP) with its varied and persistent attempts to discredit and nullify the program of democratization…. [The JCP was] less a political party and more a fifth column introducing alien ideologies into Japan.”

Organized along geographic lines, the counterintelligence organization effectively monitored and mitigated the JCP by working with and through the Japanese police, preventing any significant opposition to the successful occupation of Japan and the peaceful transition into a democratic form of government. In 1950, due to stern measures ordered by MacArthur in relation to the outbreak of war in Korea, the JCP was practically eliminated as a national entity of any influence. Although it would reemerge much later, the JCP never presented a significant threat to the occupation and democratization of Japan.

Fortunately, during and immediately after World War II, the American and Allied forces were led by intelligent, experienced, and educated men. Their primary motivation in avoiding a massive, long-term invasion of Japan was to save lives and resources. Their experiences in amphibious landings, kamikaze attacks, land warfare, and naval warfare provided ample information and statistics to use in analyzing the exceedingly difficult mission of militarily seizing and occupying the Japanese home islands.

Bringing About a Successful Surrender

Although the government of Japan agreed to surrender, it did not mean that the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and civilians would honor the terms of surrender, nor did it prevent the Japanese from changing their minds at some later date, only to resume fighting against the occupying forces. The formal signing of the surrender documents did not preclude those in the field from continuing the fight. Additionally, many combatants, especially in 1945, simply did not or could not receive word of the surrender.

Because of the Japanese stated intent to surrender, instead of landing in force as he did on Leyte Island in the Philippines, General MacArthur on August 30, 1945, took a tremendous risk and bravely flew into Atsugi Airfield in Tokyo aboard a simple cargo plane with just a small staff element before any substantial number of occupation forces were in place. He eventually met with and broadcast respect for Emperor Hirohito. His plan involved having the emperor order the Japanese people to lay down their arms and discontinue fighting, alleviating the need for American troops to forcefully invade and physically implement postwar policies under martial law.

By leaving the emperor in place and using him to order the Japanese military and general population to cooperate, MacArthur prevented that potential, enormous insurgency. His face-saving plan for the emperor ensured the greatest possible peaceful transition and reconstruction of Japan. In fact, MacArthur’s approach was so successful, the first completely free election ever held in Japan was on April 10, 1946, only seven months after the formal surrender, and it included 75 percent of eligible voters.

Conversely, had MacArthur yielded to the British and Soviet ideas by rebuking and publicly shaming Emperor Hirohito or trying him for war crimes, the entire Japanese population would have fought boldly to oppose the Allied occupying forces, which the Japanese would have perceived as attacking, blaspheming, and discrediting their deity, the emperor. Viewed in another way, had MacArthur stripped Emperor Hirohito of all his formal authority and titles and publicly shamed him by showing a humiliated, unkempt emperor—bedraggled, broken, and handcuffed or imprisoned—the Japanese would most certainly have fought against the occupying forces for years, likely decades. Hundreds of thousands of casualties would have resulted in the attempt to pacify the Japanese, and the rebuilding of the nation would have been set back many years.

SCAP’s actions in no measure dismissed Hirohito’s knowledge and tacit approval of many of the cruelties, crimes against humanity, and war crimes committed by Japanese forces and leaders. Yet, MacArthur wisely permitted Hirohito to remain in power and position as the emperor and necessarily included him in the restructuring and rebuilding of postwar Japan, at the same time ensuring their own legitimacy in the eyes of the Japanese. By December 1948, just over three years after the surrender, MacArthur declared amnesty for 17 men awaiting trial for Class A war crimes, specifically those who had led Japan during the war.

Later, he commuted death and life imprisonment sentences of many found guilty of war crimes. He also lifted the order for apprehending fugitive war criminals. He also granted amnesty to Class B and C defendants accused of abuse or atrocities. Such reconciliation was hard for many among the Allied nations to accept, but MacArthur clearly understood the benefits of forgiveness and the need to move on to rebuilding Japan. Ultimately, these policies effectively eliminated any incipient or potential insurgencies and ensured the successful restructuring of Japan along with the security and stability of 80 million people within only three years.

Unheeded Lessons of Counterinsurgency Warfare

Unfortunately, the remarkable lessons in leadership and command in countering insurgencies and conducting occupations have been lost among many who have led efforts in subsequent and similar operations. For example, the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) and Coalition forces in the early years of occupied Iraq could have used a situation for a period of time in which Saddam Hussein, or certainly some of his key ministers and military and police leaders, worked with the Coalition forces to suppress nascent insurgencies. There were several distinct insurgent organizations in Iraq. With these known leaders ordering police and military units back to duty to restore law and order, the insurgencies could have been contained and might not have developed at all, preventing years of conflict and thousands of casualties. After all, Iraqi leaders were no guiltier of atrocities than many of the Japanese leaders with whom the Allied forces worked in postwar Japan.

In other respects, the analogy between postwar Japan and Iraq or occupations of other nations diverges and is not meant to be an absolutely pure analogy with exact correlations throughout but instead a contrast. However, the general parallel and the specific actions taken by occupying forces are important and relevant, particularly for future conflicts and occupations, of which history warns there will be many.

History provides ample political and military lessons, such as those exemplified by MacArthur and validated in Japan, that permit experienced and learned, well-intentioned leaders to successfully execute counterinsurgencies, occupations, and other forms of political-military conflict.

For President Harry Truman and the Allied powers in postwar Asia, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur epitomized such a leader. Fittingly, MacArthur’s Operation Blacklist, often forgotten precisely because of its unequaled success in preventing an enormous, long-term insurrection, stands supreme above all other modern counterinsurgency and occupation operations.

Lieutenant Colonel Michael F. Trevett is a U.S. military officer with 29 years of service. He has trained or operated with the civilian, military, or police forces of over 40 nations and territories on antiterrorism, counterdrug, counterinsurgency, law enforcement, and search and rescue issues, operations, and tactics. In 2011, he published Isolating the Guerrilla, a book on counterinsurgency.

Spot on synopsis of the events as they unfolded and the sheet brilliance of General Mac’s insight. My Dad Served in the Occupational Forced of Japan as an MP in General Whitehead’s Far East Air Force HQ that was two buildings down from General Mac’s SCAP HQ and across the boulevard from the Imperial Palace. My Dad has a photo that he took of Hirohito in early ’46 when General Mac forced him to appear in public to address the Japanese People directly. He stood 20-25 feet away from him.

Your comparison with Iraq and Afghanistan are absolutely correct. To an extent, so was Vietnam.

Excellent article on the management of post-war Japan. If we had done something similar in Iraq, as the author stated, we might be in a better place. I am still struck by the way Nelson Mandela, after being imprisoned for such a long time, along with Desmond Tutu, constructed a peaceful transition when there could have been bloodshed and anarchy for decades. It’s not a perfect analogy, but it’s a lesson we must remember as historians and enthusiasts. I hope we can apply some of the lessons from this article to current conflicts worldwide.

The tradition of allowing war criminals to participate in amnesty began after WW I when no accounting was made of German crimes, particularly against civilians. The result is that war crimes continued after subsequent wars with minimal accountability. This is not to say the MacArthur’s approach was wrong, just that actions have consequences and should be better learned and planed for in future conflicts.