By Robert F. Dorr

Major Sam P. Bakshas woke up that morning with the secrets in his head.

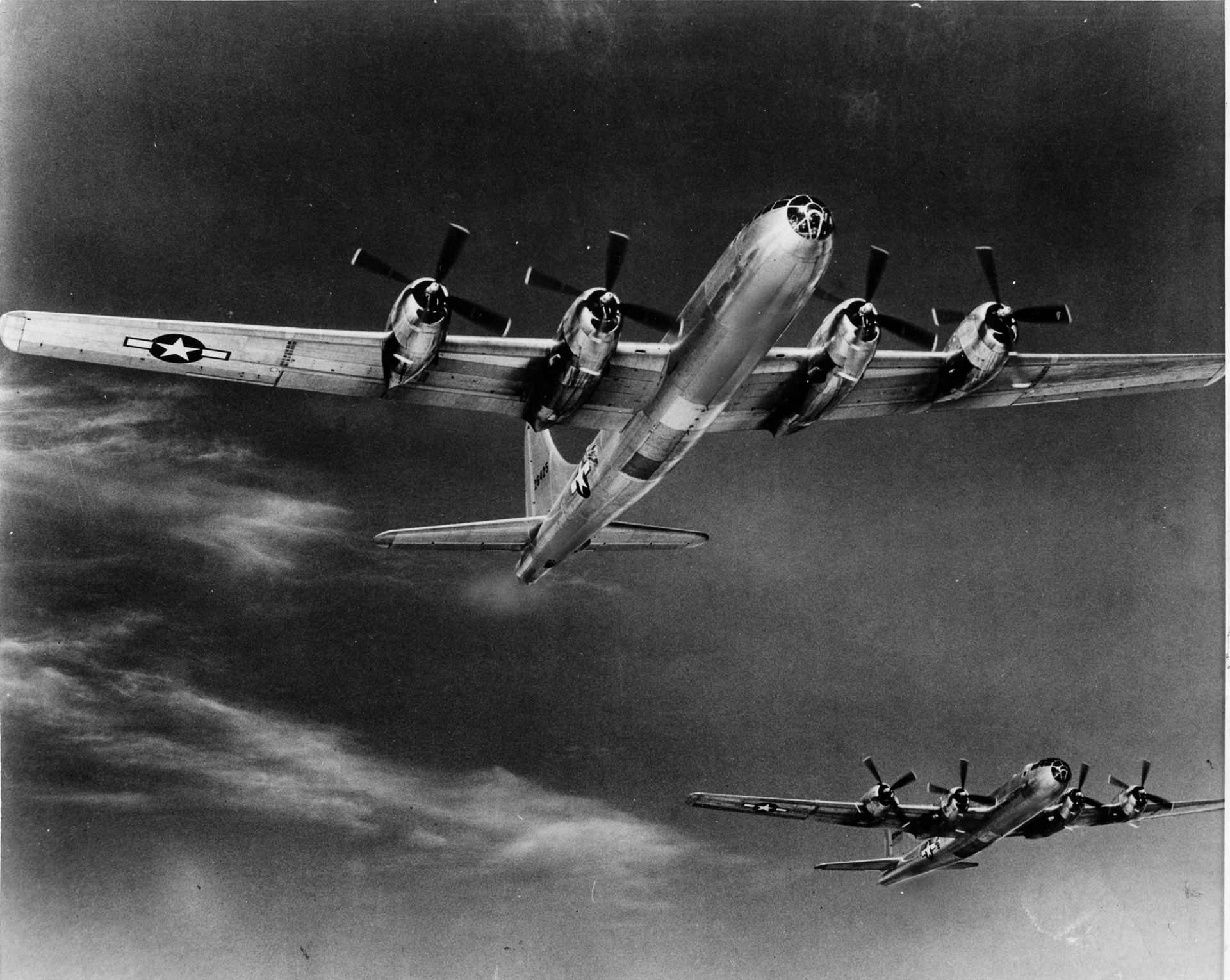

Bakshas was one of the men flying B-29 Superfortress bombers from three Pacific islands—Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. A writer dubbed these men “the thousand kids.” There were actually several thousand, and they were giving heart and soul to bombing the Japanese home islands—what they called “the Empire”—with no success. They were dropping bombs from high altitude and not hitting much. The air campaign against Japan was failing.

Bakshas believed the situation could be turned around.

Bakshas was 34. He was older and bigger than the Superfortress crewmembers around him. He was six-feet-one and almost 200 pounds. He was from Fergus County, smack in the center of Montana, and had courted his wife Aldora with the gift of an airplane ride. Today, Bakshas commanded the 93rd Bombardment Squadron, part of the 19th Bombardment Group.

In Guam’s affable climate, many B-29 crewmembers had taken scissors to their long khaki trousers to create frayed and sloppy-looking shorts. Not Bakshas. Sammy Bakshas—always Sammy, never Sam—did not understand sloppy. Bakshas was wearing long khakis and low-quarter shoes as he prepared for a day that would end with an evening takeoff.

Bakshas would be one tall guy among many today in a B-29 that was named Tall in the Saddle because no one in its regular crew was less than six feet in height. Bakshas was not a regular crewmember but would command Tall in the Saddle, relegating airplane commander Captain Gordon L. Muster to co-pilot duty.

“There was a wonderful urgency and an exhilarating secrecy about the B-29 outfits in the Marianas,” wrote St. Clair McKelway in a perspective. Even after other crewmembers began learning the two key secrets—low level, no guns—Bakshas kept them locked up, much like his buttoned-up expression, as his morning unfolded.

It was 10:30 am, Chamorro Standard Time (Guam time), March 9, 1945, the morning of the great firebomb mission to Tokyo. The B-29s would arrive over the Japanese capital in tomorrow’s early hours. It was the mission for which 21st Bomber Command boss Maj. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay changed tactics in hope of changing the war against Japan.

Staff Sergeant Carl Barthold, radio operator of a B-29 named Star Duster, began the day in his Quonset hut on Saipan by writing a letter home. The right blister gunner on Carl Barthold’s bomber crew was certain that none of them would return from tonight’s mission. He stuffed everything he owned into his B-4 bag—the multipocketed, fabric-covered equivalent of a travel suitcase—and left his belongings tidily packed in the center of his cot.

“He said he was looking at his possessions for the last time,” explained Barthold.

Barthold, a radio operator with the 870th Bombardment Squadron, 497th Bombardment Group—a rail-thin, 21-year-old Missouri boy at five-ten and a lightweight 142 pounds—wore underwear and clogs trudging to and from the shower, a hundred yards uphill from his Quonset.

Outdoors, he had a spectacular view of Aslito airfield, now renamed for Navy Commander Robert H. Isely, who had been killed a year earlier strafing the place when it was in Japanese hands. Isely’s name was spelled wrong when the name was bestowed, and the airfield was now Isley Field. Its two parallel 8,500-foot runways were straddled by parking spots for 100 aircraft, looking like giant silvery cigars with wings.

“That guy has me spooked,” Barthold said aloud when he looked at the B-4 on the cot. That’s how it would have looked if Didier had gone to heaven, but as far as Barthold knew he had only gone to chow.

Two months ago, Barthold had had a bombardier die in his arms high over the Empire. Last night, Barthold and the rest of the crew of his B-29 had gotten a casual heads up from airplane commander Captain James M. Campbell, who had been told the secrets—low level, no guns. Barthold and his crew would take off this evening, climb into the night, and assault Tokyo not from the usual height of 28,000 feet—from which their bombing hadn’t been accurate—but at low level at around 8,000 feet.

Saipan, with its tall cliffs from which so many Japanese had flung themselves in suicide leaps when the Marines were in the process of securing the island, was a place of raw beauty with deep blue, wave-capped ocean readily visible on all sides. And it was a place from which a B-29 Superfortress could plummet down toward the sea after leaving the runway’s end, taking a pronounced dip before gaining sufficient power to climb aloft—or go smashing into an ocean that could crumple it and swallow it up.

It was 11:30 am, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945. Within easy eyesight of Saipan was Tinian—38 square miles of coral rock, dust, jungle, and cane fields, crowded with B-29 hardstands. Tinian was a little green slab formed by prehistoric volcanoes and dead coral animals. Tinian’s North Field boasted three crushed-coral runways 8,500 feet long and 200 feet wide, running parallel, with a fourth soon to be added and with parking revetments for 265 Superfortresses, making it the busiest airport in the world.

Tokyo (code name: Meetinghouse) was Japan’s largest city, built along the edge of a big, gently curving bay. It was the center of Japanese life. For symbolic reasons, the Americans planned not to bomb the Imperial Palace, but the rest of the city was fair game with its military assembly plants and vehicle factories. Moreover, it was home to a cottage industry in which tens of thousands of Japanese families manufactured small parts for the military. The wood and paper houses that would fall beneath LeMay’s firebombs were also factories.

About six million people lived in Tokyo on the eve of the B-29 strike that would kill many inhabitants, send more fleeing to the countryside, and reduce the city’s population by fully half. Astonishingly, the city had only a token fire department and almost no civil defense infrastructure. It was a city of fragile houses with sliding shoji screens, floored wooden roka or passageways, and fusuma, or partitions of wood and paper. It was no accident that the Americans were coming to Tokyo with fire.

On tonight’s mission, E-46 chemical incendiary bombs would rain down on Japan like giant firecrackers. They came in bunches of 47 small bomblets called M69s, strapped together inside a metal cylinder fused to break open at 2,000 or 2,500 feet. Three to five seconds after the big firecrackers hit, they would go off. An explosive charge would violently eject a sack full of gel that would burn intensely.

The sack held the gel in one spot, thereby igniting a hotter fire. Other weapons being employed today were the E-28 incendiary cluster bomb and the M47, a petroleum-based bomb that would be carried by the lead B-29 piloted by the in-air commander of the mission, Brig. Gen. Thomas “Tommy” Power—and would penetrate buildings and scatter gel in all directions to burn out the insides.

It was 1 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945. In the terminology of Field Order No. 43 issued at 8 am on March 8, 1945, by 21st Bomber Command, Tokyo was “the urban area of Meetinghouse.” The order tasked men like Bakshas on Guam (in the 314th Bomb Wing) to attack at 5,000 to 5,800 feet, those on Tinian (313th Bomb Wing) to strike at 5,000 to 5,800 feet, and those on Saipan (73rd Bomb Wing) to bomb at 7,000 to 7,800 feet. No armada of warplanes had ever before been launched in such numbers without flying in formation. No American heavy bomber had ever flown so low on a mission against a major target.

Depending on the island—Guam, Saipan, or Tinian—and depending on the bombardment group (a dozen in all), the briefing for the March 9-10 mission to Tokyo was held at different times throughout Friday the 9th. Most B-29 crewmembers shuffled into giant Quonset huts where crews sat together and stared up at maps and charts. The group commander, the intelligence guy, and the weather officer each took his turn to strut and fret on the stage.

At the briefing for the 19th Group on Guam, some kind of conversation with a bit of an edge took place between 93rd Squadron commander Bakshas and airplane commander Muster. Apparently, there was tension between the two over the risks in tonight’s journey to the Empire.

At the 497th Bomb Group on Saipan, Carl Barthold’s briefing was held inside a large concrete building. The intelligence officer talked too long about Japanese antiaircraft guns, fighters, and mistreatment of prisoners. Said Barthold, “My plane was a pathfinder and we would be taking off 45 minutes before the rest of the wing. The intel officer, who’d never seen the Empire from the air, wasn’t much help.”

Similar briefings took place on Tinian. Fears were quietly discussed. Many of the “thousand kids” were terrified of the prospect of ditching at sea. Of 48 Superfortresses known to have put down in the Pacific so far with 528 airmen aboard, air-sea rescue had picked up just 164. An elaborate system that used PBY Catalina and PBM Mariner aircraft, seaplane tenders, and submarines was taking shape, but B-29 crewmembers knew that the ocean was vast and a bomber could be reduced to a tiny speck bobbing on the waves. Worse, many B-29s were short of Mae West flashlights because crewmen borrowed them for use in their quarters and forgot to bring them along.

At Saipan’s Isley Field in late afternoon with the dull yellow sun sneaking in and out of tropical rain clouds, Barthold and the Campbell crew piled out of a truck at the hardstand in front of their looming, four-engined heavy bomber.

In brighter light, the plane’s silver surfaces would have gleamed. It was a thing of beauty to some, but mostly, the B-29 looked functional, its cigar-shaped fuselage confronting Barthold, its 141-foot wing spread in front of him with the four-bladed propellers ready to turn. The ground crew was finishing its final checks, having spent many hours since last night inspecting systems, loading bombs, and loading fuel.

“There were 12 pathfinder planes in our group,” Barthold said. “We were to take off a half hour before everybody else. We were to arrive first and put a big X across Tokyo for those coming behind us to see.”

Some airplane commanders required a lineup inspection at planeside. Barthold said, “Our plane commander [Campbell] had confidence in us. We didn’t hold a formal inspection. The ground crews had our gear, including our Mae Wests, already on the plane. Our plane commander let us behave like adults as we checked our own gear, climbed aboard, and prepared to take off.”

With the rest of the crew, Barthold entered the aircraft by climbing up into a dark space behind the nose wheel. Once seated in his radar compartment he could hear the pilots and flight engineer on the interphone, running through the engine-start checklist.

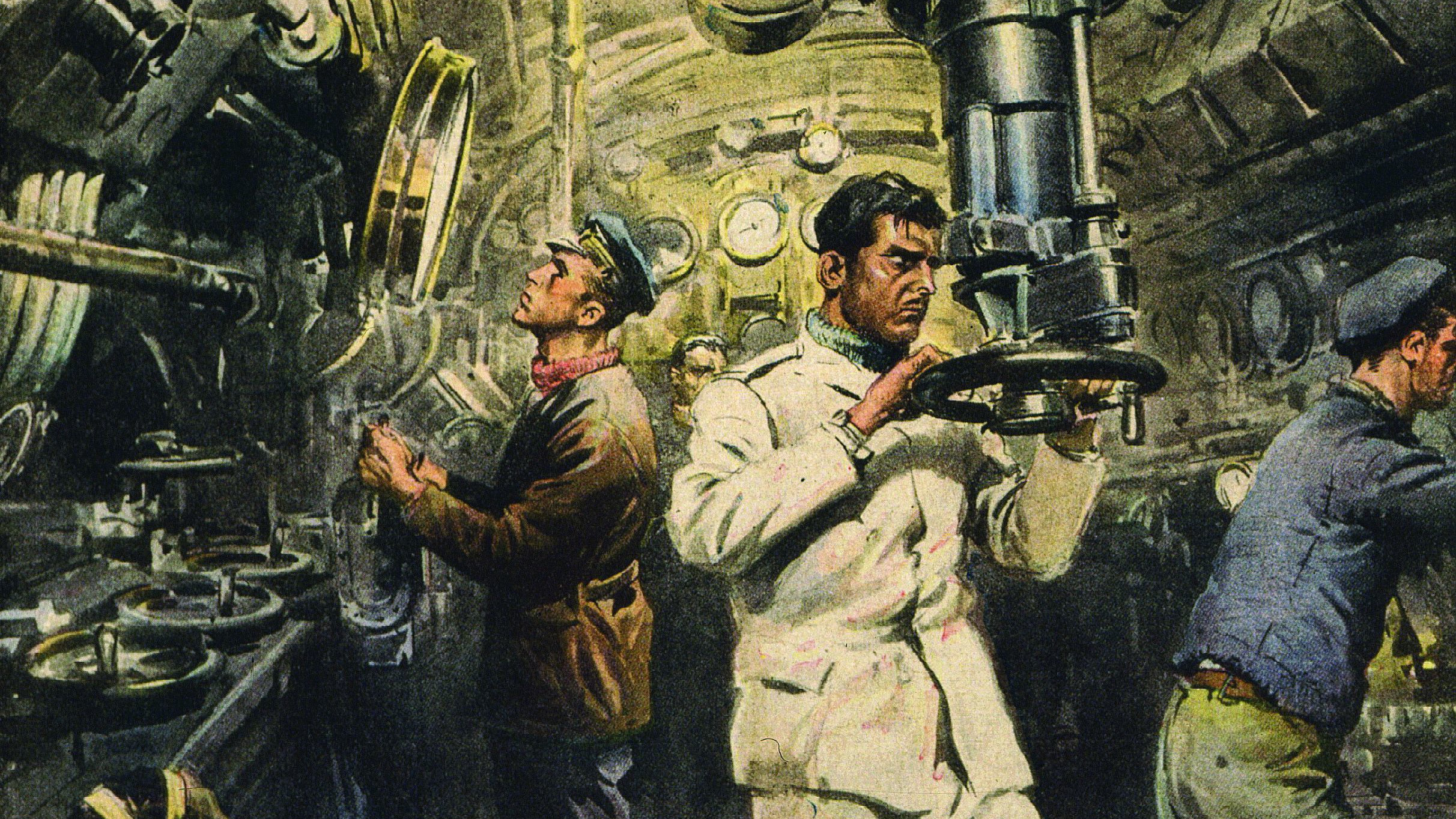

“I was the radio operator,” Barthold said. “I sat next to a bulkhead facing the right side of the plane. I had my radio, key, and codebooks. I was jammed in there. I was in a little chair that infringed on the upper and lower gun turrets, and I was facing to the right. My head pressed up against the four .50-caliber machine guns in the upper turret, and they always used to rattle in my head.

“Across from me was the navigator, who faced forward. In front of me but separated by a partition was the flight engineer, who faced to the rear. Were we all a little more nervous than usual because we were going to Tokyo at low altitude? Yes. Yes, we were.”

Barthold’s B-29 trembled, and the noise level went up as the engine-start procedure began. It was 5:15 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945.

Takeoff was a tense time. Takeoff for Tokyo in a B-29 fully loaded with fuel, bombs, and ammo was a dangerous proposition. Almost everyone on Guam, Saipan, and Tinian had seen one crash. If you lost an engine past the halfway mark of the takeoff run, you probably would not be able to stop before the end of the runway, and the plane would crash off the cliff or go into the water and explode.

But, as Barthold was well aware, on Saipan at least there was a margin of safety if it was used correctly. At Isley Field it was common on takeoff for the pilot of a fully loaded B-29 to hold the wheels to the runway until the final few hundred feet (the last two percent of the runway’s length), hauling back at the last possible instant to lurch over the road along the cliff edge, then diving full throttle for the sea far below, gaining airspeed while retracting the wheels and finally beginning the long takeoff climb as the belly of the plane virtually skimmed the water. More than one of the crews failed at this maneuver, especially at night.

Before dusk, the pathfinders were in the air while crewmembers of the remainder of the attack force of 334 B-29s on three islands were climbing aboard their planes. Because Guam was farther from Japan, its B-29s were already taxiing out.

Closely observing the noisy, busy preparations was LeMay. To St. Clair McKelway, the general’s public relations officer, there was “something deeply, bottomlessly disturbing in this stocky, plain-looking new commanding general.” LeMay was only one of many who had thought of using firebombs to ignite Japanese urban areas, but he alone bore responsibility for ordering his men to attack at low level and to leave their ammunition behind.

LeMay wasn’t at the controls of a B-29 for today’s Tokyo mission because General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold had made him part of a small inner circle who knew about a supersecret U.S. program to create a new weapon—the atomic bomb. No one with that knowledge could be permitted to risk falling into Japanese hands.

LeMay and his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. August Kissner, were in a jeep at North Field, Guam, as late afternoon blended into evening. They watched as Power led the first B-29s into the sky. It was 5:36 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945.

Tall in the Saddle, with Sammy Bakshas in the airplane commander’s seat, made a smooth takeoff not far behind Power. They climbed into the early evening sky while B-29s were still warming up on Saipan and Tinian. Bakshas and Muster were now among the most experienced of B-29 pilots and, when teamed with their flight engineer 2nd Lt. Leland P. Fishback, they could make the huge bomber perform miracles. This was a B-29 crew at the top of its game.

Tall in the Saddle, climbing, was in fine shape. Not a nick, not a scratch spoiled the smooth, natural metal skin of the Superfortress. Her four R-3350 engines, treated lovingly by the ground crew assigned to Muster, were purring smoothly—something the trouble-prone R-3350 did not always do.

It was 6:05 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945.

Takeoff for Tokyo

When they began their takeoff roll, many B-29 crewmembers believed that their humorless, cigar-chomping commanding general, LeMay, was sending them to die.

Not sure they were wrong, LeMay spent the early evening hours watching B-29s take off from Guam in fading daylight. He told McKelway, “If I am sending these men to die, they will string me up for it.” LeMay later told aide Lt. Col. Robert S. McNamara, “I was under pressure from people who didn’t want a change in the way we were doing things. I felt I had to ignore them and take a chance.”

It took two hours and 45 minutes for 334 B-29 Superfortresses to take off, one to three minutes apart, from six runways on Guam, Tinian, and Saipan. No one had ever sent this many bombers aloft in so short a span of time. Some planes were tucking in their gear and climbing out while others were still turning engines. The choreography may not have been perfect, but the beginning of the mission to Tokyo was going as smoothly as anyone could expect. The largest force of bombers ever assembled in the Pacific was off to a good start.

One of the first pathfinders to lift skyward was radio operator Carl Barthold’s airplane. Once he could reassure himself that he had survived takeoff, always a tense time, Barthold was gifted with time to do what military men have done since war was invented—hurry up and wait. His radio operator’s station was a mini-office surrounded by gadgetry, wires, and codebooks. Barthold sat facing the outer skin of the fuselage with the back of the flight engineer’s panel to his left and the bomb bay bulkhead to his right.

He had enough room not to feel claustrophobic but only one small aperture that gave a glimpse of the sky and sea outside, growing darker as night descended. Much of his world consisted of the wires and dials of his four-channel, high-frequency SCR-522 command radio set. He wore earphones and had a microphone handy.

“Goddamn LeMay’s going to get us killed,” somebody said on the interphone.

“Cut it out,” said the voice of airplane commander Campbell. “Let’s have some interphone discipline, gentlemen.”

The Tokyo mission was in the air. Of the 334 aircraft that took off from three islands, 279 were going to make it all the way while the remainder aborted for technical reasons.

There was no formation. Each aircraft was on its own, its airplane commander entrusted with the souls on board, its navigator and his special skills never more important than now. The pathfinders were way out in front with most of the bomb groups from Guam coming next, having taken off early enough to overtake the Superfortresses from Tinian and Saipan.

Power’s 314th Wing from Guam was assigned to approach Japan flying between 5,000 and 5,500 feet. Brig. Gen. Emmett “Rosy” O’Donnell’s 73rd Wing from Saipan was to fly between 3,000 and 3,500 feet while Brig. Gen. John H. Davies’ 313th Wing on Tinian was to make the long journey to the Empire at 4,000 to 5,000 feet. The separation of bomb wings by height above a dark and cruel sea was the best hope of preventing air-to-air collision—and, in fact, none occurred.

Anyone familiar with precision daylight bombing formations in Europe—stepped, spaced, boxed aerial assemblages of bombers proceeding together in book-like unison—would have believed that LeMay’s entire B-29 force had lost all sense of discipline or, even, of common sense. Perhaps the men at the controls of these planes were completely mad.

A B-29 gunner recalled, “Occasionally on a night I would look out my blister at the ocean down below and it would look like we were passing over a series of connected super highways with lights. What I was observing were lines formed in the currents of fluorescent sea life. It was eerie, not in a comforting way but in a troubling way.”

While a bomber was droning toward its target there was too much time to think. Another Superfortress gunner recalled dwelling on the terrible danger of an over-water bailout, which was even more fearsome than a ditching. “Many opened their chute harnesses early so they could get out and not be fouled by their chute in the water. The admonition was, ‘Do not attempt to judge your height and jump from your harness until your feet are wet.’ Over a calm sea it is very difficult to tell if you are at 100 feet or 1,000 feet—even in daylight!”

The weather in and around Tokyo painted a confusing picture. Because the bomber men planned to burn down the Japanese capital, their leaders had waited for a night when the air was dry and there was wind in the target area. The wind, of course, would spread the fire. It was indeed dry and windy at the capital, but all manner of weather conditions were roiling up in the region. Snowstorms were churning in several locations near Tokyo.

It was 9:30 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945.

Boring through the night sky was Tall in the Saddle with Bakshas in the left front seat watching instruments, keeping a grip on the control yoke, working with Muster and Fishback, monitoring changes in the behavior of the four engines, and checking in frequently with navigator John Hagadorn. Muster was annoyed. He and Bakshas had gotten along famously until today, but Muster felt his squadron commander was overstepping by taking the pilot-in-command role.

In many ways, the most important crewmember on the long journey toward the Empire was Hagadorn.

If he screwed up, nothing else would matter.

Hagadorn kept up with the position of the plane at all times through dead reckoning (keeping track of speed, direction, and changes in course) and making observations of celestial objects. When he wanted to make a “fix” with his hand-held sextant, Hagadorn crawled into the tunnel above the bomb bay and looked up into a transparent astrodome. It was 11:30 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945.

Hours passed. The dark sea rushed beneath the B-29s. Tokyo drew nearer. On Guam, many on LeMay’s staff caught up on their sleep with the general’s permission. LeMay usually had no difficulty sleeping, but tonight he was wired up. He would not know until the main force began to bomb Tokyo two hours after midnight whether his shift in tactics was a brilliant stroke or a death warrant. LeMay always looked grim because of a condition called Bell’s palsy, which paralyzed facial muscles near his mouth and made it almost impossible for him to smile.

The general in command of thousands of bomber crewmembers was alone in his Quonset headquarters but for St. Clair McKelway, who had become a confidant and who had been told to wait to hear the “bombs away” message expected in early morning. LeMay and McKelway exchanged small talk. Neither was good at it. Both felt the tension as they awaited news from Tommy Power at the cutting edge of the attack force.

LeMay talked of his wife and child back in Cleveland. This was out of character. McKelway wrote that LeMay had no life “beyond games of medicine ball to keep fat off a body that tends toward fat, games of poker to relax as best he can a mind that actually never stops thinking about how to do the job better the next day, and a little reading, mostly fairly serious, to improve a mind he considers inadequate.”

With midnight approaching and the first pathfinders due over the Japanese capital, a curious kind of loneliness bonded McKelway and LeMay. McKelway sensed it was as if there was no difference in rank between them. “We won’t get a bombs-away for another half-hour,” LeMay said, looking at his watch. “Would you like a Coca-Cola? I can sneak in my quarters without waking up the other guys and get two Coca-Colas and we can drink them in my car. That’ll kill most of the half hour.”

They drove the hundred yards to LeMay’s tent in his staff car, and he sneaked in and got the sodas. “We sat in the dark, facing the jungle that surrounds the headquarters,” McKelway wrote—two men, no rank between them now, pulling on the six-ounce Coca-Colas and knowing that within a very short time the thousand kids would be arriving over the Empire. It was 11:50 pm, Chamorro Standard Time, March 9, 1945.

Tokyo Alight

So were Tokyo’s streetlights really lit up before the bombers arrived? Some B-29 crewmembers said the city was aglow when they arrived, with no sign of a blackout in effect.

Some B-29 crewmembers listened to Japanese radio stations while they flew toward the Empire. A crew led by Captain Thomas Hanley of the 497th Bomb Group entered the final hours of the approach to Tokyo listening to a song whose title they would remember with irony: “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.”

The weather that night was a quarter-moon. Most B-29s were making a key turn at Choshi Point, east of Tokyo, the IP, or initial point, where they would turn west to begin their planned run-in. Crewmembers squeezed into their flak vests, heavy and cumbersome garments with steel plates that could absorb shrapnel. Some donned helmets that interfered with earphones but promised head protection. None saw any night fighters. Antiaircraft gunfire would be a formidable adversary, but the fighters were somehow missing.

The defense of Tokyo was a paradox. Americans were warned about and on occasion reported seeing barrage balloons, gas-filled aerial bags that were used to string vertical cables in the path of approaching airplanes. Yet, the Japanese had never had any. Japan had night fighters and very capable night-fighter pilots, yet most Americans never saw one. At night, Japan’s network of antiaircraft guns and searchlights could be terrifying, and sphincters tightened whenever a searchlight beam locked onto a bomber, yet there appeared to be little coordination between the guns and the lights.

An intelligence summary credited the Tokyo region with 500 antiaircraft guns, “as many guns as ever protected the German capital of Berlin.” Bomber crewmembers feared these guns, yet they were never as effective as their German counterparts.

Radio operator Carl Barthold remembers being briefed that the Japanese antiaircraft guns were effective from the ground up to 5,500 feet but that a “gap” existed going up to about 10,000 feet where coverage resumed. The need for coverage above 10,000 was obvious because the Americans had wasted many months flying at great heights. “We were told that we were going in through a ‘window’ where they wouldn’t have the capability to shoot us.”

Sammy Bakshas of Tall in the Saddle would learn that that wasn’t quite true. Yet the Americans were approaching a city where every manner of lip service had been paid to defending the urban area and its population, but few practical measures actually had any impact.

Japanese cities had been equipped with air-raid sirens, blackout facilities, and underground shelters for almost 20 years, yet people at home and on the street often ignored them. In Tokyo, shelter construction, especially in the area near the bay, was complicated because they could not be dug more than a few feet without encountering ground water. Many people simply stayed where they were when the bombers approached. Perhaps inured by the apparent inability of the Americans to hit anything with their bombs, urban residents dismissed the appearance of the bi ni ju ku, the B-29, as a “mail run.”

The previous day, a strong wind had been rattling the panes in doors and windows all over the city, the same wind the Americans hoped would spread the fire they were bringing, and most people had gone about their day routinely. For the past few nights single B-29s had appeared over the city, not dropping any bombs but flying very low and setting off the searchlights and antiaircraft fire. This was reconnaissance and it made many in the capital uneasy, yet routine activities continued, and after dark the lights may have stayed on.

Or they may not have. Yukiko Hiragama, called Yuki, an eight-year-old schoolgirl who happened to be outdoors that night, remembers nothing about street lights. “Before the bombers came it was a night of darkness and shadows,” said Yuki. “The sirens made their powerful sounds in the evening and then night came and there were no B-29s. The sirens were silent and the lights were off when the B-29s arrived.” While Yuki remained awake, most in Tokyo went to sleep after the sirens halted, many of them hungry because food supplies were short.

The bombers came, beginning with the pathfinders.

Also awaiting the arrival of the B-29s were Japan’s fragmented air defense network and Tokyo’s nearly dysfunctional civil defense system.

Airfields were scattered all over the Tokyo region, but the job of defending the capital belonged to the Japanese Army’s 10th Flying Division, with 210 fighters. Tonight, as it would turn out, the low-level B-29 approach took the fighter force by surprise. In the early minutes of Saturday, March 10, 1945, they were receiving little direction from ground controllers, and their flights were not coordinated with searchlight and antiaircraft batteries. Fighters prowled the Japanese coast, but their pilots had no guidance from ground radar stations and never came within eyesight of a B-29.

The Army was responsible for antiaircraft gun batteries in and around Tokyo. As LeMay had hoped, they were not prepared to engage B-29s at low altitude.

It was 00:15 am, Chamorro Standard Time, March 10, 1945.

The B-29 main force arrived over Tokyo, Barthold working his radio as part of the Campbell crew and listening in the night for signals; the Bakshas crew in Tall in the Saddle … they were arriving, all of them, and as fire began to spread in Tokyo, the sound of R-3350 aircraft engines overhead grew to a rolling thunder.

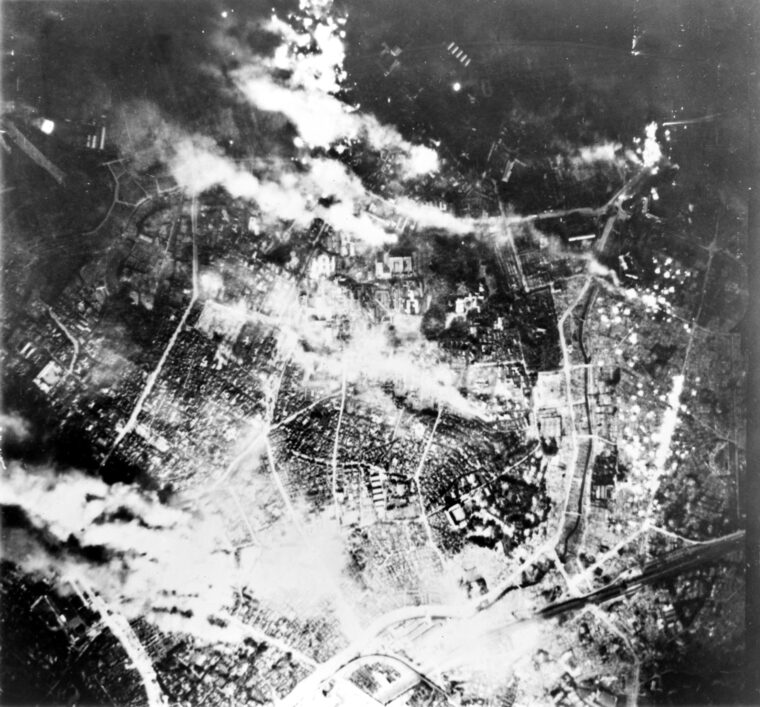

LeMay’s B-29s dropped nearly half a million M69 incendiary bomblets on the Japanese capital in the early hours of March 10, razing 16 square miles of the city, transforming darkness into an eerie artificial light, and immersing tens of thousands of human beings in raw heat against which there was no defense.

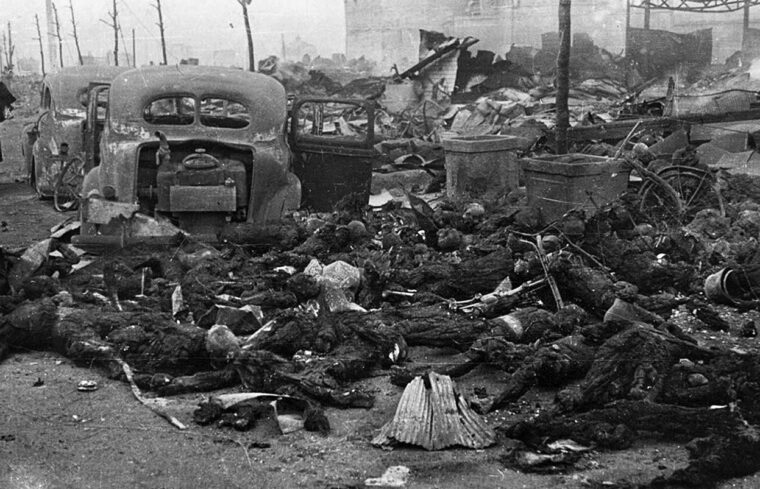

Joseph Coleman of the Associated Press wrote, “The M69s released 100-foot streams of fire upon detonating and sent flames rampaging through densely packed wooden homes. Superheated air created a wind that sucked victims into the flames and fed the twisting infernos. Asphalt boiled in the 1,800-degree heat. With much of the fighting-age male population at the war front, women, children and the elderly struggled in vain to battle the flames or flee.”

McNamara quoted LeMay as saying, “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” “And I think he’s right,” added McNamara. “He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost.”

The real crime in Tokyo on the morning of March 10 was that the authorities were unready. Civil defense, emergency response, and firefighting personnel were shamefully—criminally—unprepared to handle an all-out assault from above.

There was no defense ordinary people could take against a confetti of exploding M69s. Smothering a bomb with a blanket didn’t work. In Tokyo, the authorities had sought to equip each household with a grappling hook, a shovel, a sand bucket, and a water barrel. They were useless. In all of Tokyo, there were almost no air-raid shelters.

The Tokyo fire department was pitiful. In recent months, its strength had increased from 2,000 to 8,100 firefighters. The fire department of New York, which no longer faced any likelihood of being bombed from the air, was made up of almost 10,000 firemen. In 1943, the Tokyo department had 280 pieces of fire apparatus. In early 1945 it had 1,117 pieces. A shortage of mechanics idled more than half of them.

Heat and Horror

It began just after 11 pm Tokyo time, or midnight according to the Chamorro time by which the Americans set their watches. Sirens sounded.

The pathfinders, radio operator Barthold among them, began dropping the self-scattering incendiaries the Japanese called molotoffano hanakago, or “Molotov flower baskets,” inscribing an “X” throughout the target zone. After a brief pause, the main force of B-29s—400 miles long—spent 21/2 hours passing over Tokyo.

They unleashed a fire that was more severe than the conflagrations that razed Moscow in 1812 and San Francisco in 1901, even the fire that followed Tokyo’s terrible earthquake of 1923. Even taking the subsequent atomic bombings into account, they ignited the hottest fires ever to burn on Earth.

Once the flames came, there was no escape. In 30 minutes, the fires were out of control.

The conflagration quickly overwhelmed Tokyo’s wooden residential structures. The firestorm replaced oxygen with lethal gases, superheated the atmosphere, and caused hurricane-like winds that blew a wall of fire across the city.

Kiyoko Kawasaki, a 36-year-old mother, ran into the street with two buckets on her head for protection, jogging into a sea of fire and seeing burning bodies floating in the Sumida River. “The prostitutes who hung out by the riverbank jumped into a nearby pond,” she recalled. “But the pond was boiling so they all died.”

Twelve-year-old middle school student Yoko Ono saw the inferno from nearby and felt the heat. Yoko was part of the privileged elite in a society where stature meant everything, a stern-looking child whose father, a banker, was being held in an Allied prison camp in Hanoi in Indochina. She hoped to break away from the privileged class of her upbringing to become an artist.

As the firebombing progressed, Yoko took shelter with her mother and two tiny siblings in a special bunker reserved for those near the top of the social hierarchy. It was in the Azabu district of Tokyo, within eyesight of the burning carnage but at a safe distance. As soon as they could get free, Yoko’s mother and the three children joined neighbors in a headlong flight away from the burning city, out into open country.

But farmers in the countryside were starving and unenthusiastic about sharing food with a horde of urban refugees. In the weeks ahead, reduced to foraging from farm to farm, Yoko’s family experienced hard times. She begged for food while homeless and pushing family belongings in a wheelbarrow. “I did not need to be told about hardship,” she said. “I experienced it.”

30 Seconds Over Tokyo

One of the casualties in the flickering sky near a burning Tokyo was Zero Auer, a B-29 piloted by airplane commander 1st Lt. Robert Auer of the 19th Bombardment Group from Guam. An Auer family member later wrote of “the brute physical challenge” of controlling the 65-ton Superfortress while it was being batted around like a toy—demanding every ounce of muscle that Auer and 2nd Lt. Harold D. Currey, Jr., could muster.

An antiaircraft shell hit the Zero Auer dead center, possibly detonating inside the open bomb bay. Zero Auer traveled several miles north of Tokyo and then was seen to break into three distinct pieces, with red-orange torrents of fire pouring out of the gaps. One crewmember bailed out, but the others perished. It was 2:05 am, Chamorro Standard Time, March 10, 1945.

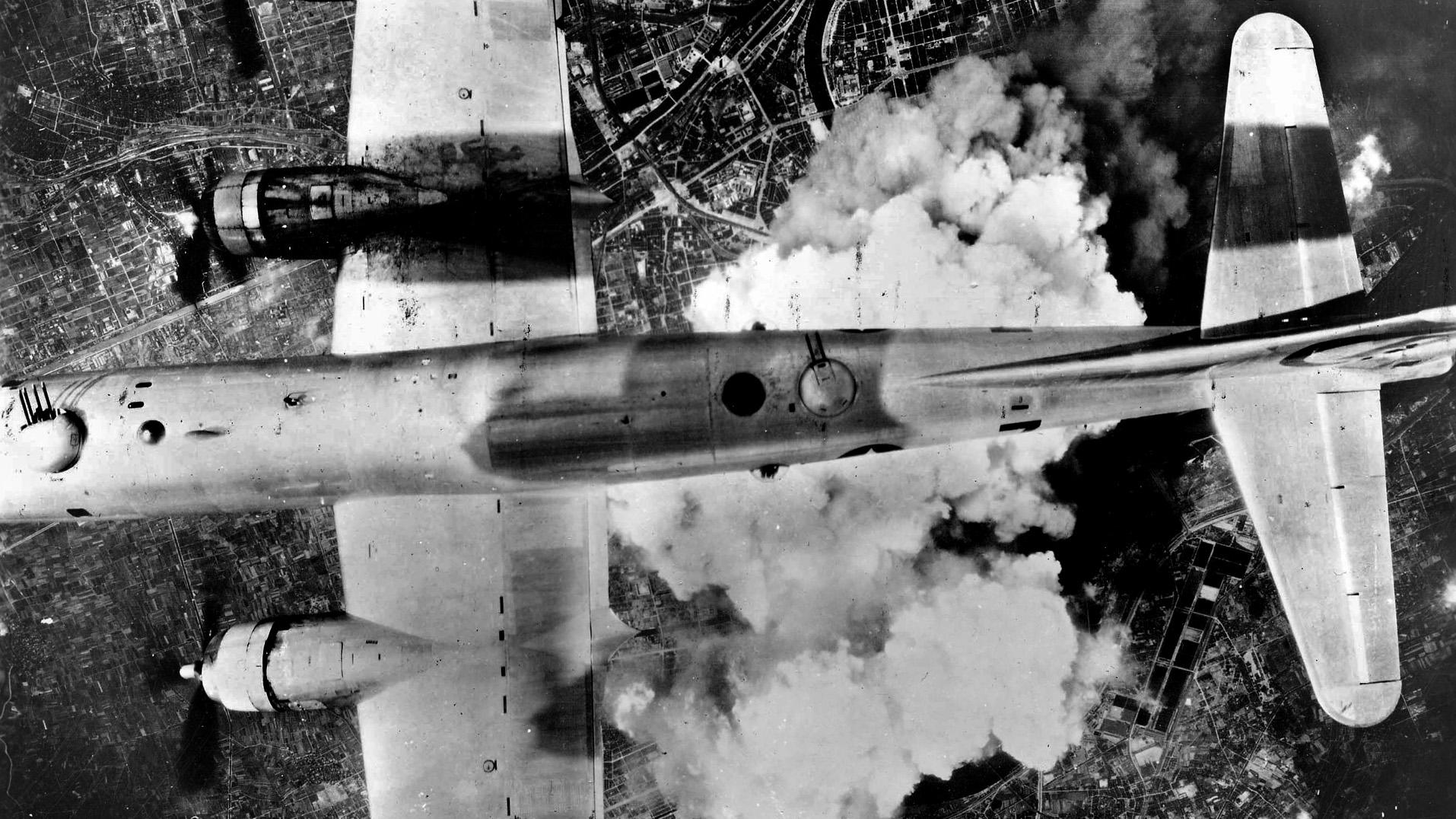

A third of the way through the procession of B-29s over Tokyo, Japanese antiaircraft artillery connected with Tall in the Saddle and its 11-man crew.

Just after “bombs away,” an exploding flak shell made a direct hit on Tall in the Saddle. According to the missing aircrew report, the B-29 was shot down in a location that is “unknown” and at a time that is “unknown.” Directly over the gathering firestorm, the Bakshas bomber appeared to halt in mid-air, tilted strangely, and descended, fire spurting back from its wing fuel tanks.

Tall in the Saddle was the only Superfortress to be shot down directly over the Japanese capital and to fall into the center of the target area. It would have taken between 30 seconds and one minute for a B-29 to traverse the nearly 16 square miles of densely-packed Tokyo that were now white-hot with flames—burning so intensely that ashes streaked the noses of B-29s a mile overhead, while crewmembers could smell burning flesh. Tall in the Saddle appears to have been struck by a direct hit squarely at the mid-point of that traverse.

Brigadier General Thomas S. Power—Tommy—the overall air commander of the mission, stayed over the target for 90 minutes. Power was making red crosses on a hand-held map to show blocks where fires broke out. He wore his red crayon down. Crewmembers were becoming nervous. No one liked lingering this long over a well-defended target.

In a report, Power wrote, “The best way to describe what it looks like when these fire bombs come out of the bomb bay of an airplane is to compare it to a giant pouring a big shovelful of white-hot coals all over the ground, covering an area about 2,500 feet in length and some 500 feet wide.”

Power may have been the hardest man among the thousands of Americans over Tokyo that morning, but he was not unmoved by the human suffering beneath his wings. As he kept looking down, he occasionally wiped his eyes. One crewmember believes the words “poor bastards” escaped from his lips.

Power’s was one of the last B-29s to depart the target. It was 3:05 am, Chamorro Standard Time, March 10, 1945.

Second Lieutenant Hubert L. Kordsmeier was airplane commander of a B-29 Superfortress of the 498th Bombardment Group flying from Saipan. For reasons that may remain forever a mystery, shortly after depositing their firebombs on a burning Tokyo, three B-29s from three different bomb groups—two from Guam and one from Saipan—flew into the same mountain in Japan at about the same time. Kordsmeier’s was first. It was 3:40 am, Chamorro Standard time, March 10, 1945.

How could three planes fly into the same mountain? And how did three B-29s end up a hundred miles northeast of Tokyo? Kordsmeier and his pilot, 2nd Lt. Claude T. Dean, must have struggled with the controls before slamming into 5,657-foot Mount Fubo in the Zao Mountains.

Cherry the Horizontal Cat, commanded by Firman Wyatt of the badly battered 29th Bombardment Group operating from North Field, Guam, was the second of the three B-29s that went into the slope of Mount Fubo. Captain Samuel M. Carr was airplane commander of the unnamed third Superfortress to collide with the looming slope in darkness and swirling snow. Again, all aboard were lost.

It was 3:30 am, Chamorro Standard Time, March 10, 1945. The great firebomb mission was wrapping up.

The “all clear” sounded at 2:37 am Tokyo time, or 3:37 am on the clock used by the Americans. Stacked blackened corpses were being hauled away on trucks. Tokyo resident Fusako Sasaki said she saw “places on the pavement where people had been roasted to death.”

Mark Selden, who wrote in Japan Focus, contends that the widely seen figure of 100,000 who ultimately died in the bombing is misleading. Wrote Selden, “The figure of roughly 100,000 deaths, provided by Japanese and American authorities, both of whom may have had reasons of their own for minimizing the death toll, seems to me arguably low in light of population density, wind conditions, and survivors’ accounts.

“With an average of 103,000 inhabitants per square mile (396 people per hectare) and peak levels as high as 135,000 per square mile (521 people per hectare), the highest density of any industrial city in the world, and with firefighting measures ludicrously inadequate to the task, 15.8 square miles of Tokyo were destroyed on a night when fierce winds whipped the flames and walls of fire blocked tens of thousands fleeing for their lives. An estimated 1.5 million people lived in the burned out areas.”

Weeks later in an Army publication, Staff Sergeant Bob Speer wrote, “The great city of Tokyo—third largest in the world—is dead. The heart, guts, core—whatever you want to call everything that makes a modern metropolis a living, functioning organism—is a waste of white ash, endless fields of ashes, blowing in the wind. Not even the shells of walls stand in large areas of the Japanese capital. The streets are desolate, the people are dead or departed, the city lies broken and prostrate and destroyed.

“The men who accomplished the job study the photographs brought back by their recon pilots … and stand speechless and awed. They shake their heads at each other and bend over the photos again, and then shake their heads again, and no one says a word.”

Vast warehouse areas, big manufacturing plants, railroad yards, stocks of raw materials, the whole complex of home factories—all of it was gone. The broadcast studio JOAK, from which the voice of Tokyo Rose was sent out to taunt B-29 crewmembers, was heavily damaged. The Imperial Hotel, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, needed serious repair. The biggest railroad stations in Asia—Ueno and Tokyo Central—were completely wiped out.

The torching of Tokyo and Emperor Hirohito’s subsequent viewing of the ravaged sections of the city are said to have marked the beginning of the emperor’s personal involvement in the peace process.

After 15 hours and four minutes in the air, the great Tokyo firebomb mission’s on-scene air commander, Brig. Gen. Thomas S. Power, landed at Guam’s North Field. There were dark circles around Power’s eyes. The aircraft came to a halt, and two of its engines were still running when Power dropped to the ground.

LeMay greeted Power with a hint of a smile. St. Clair McKelway looked on and tried to read the two men. Power told LeMay that antiaircraft fire had been lighter than he’d expected, Japanese night fighters had not been seen, and the fires in Tokyo, which ultimately combined into a single vast conflagration, had been more devastating than anyone expected.

Three B-29s ditched after the mission to Tokyo. Of 334 bombers launched against Japan in the early evening hours of March 9, 1945, some 279 aircraft arrived over target and passed over the primary aiming point at “Meetinghouse,” the center of Tokyo. B-29 Superfortress crews brought home with them the stench of burnt death.

Back from the mission, in the sunlit morning, 1st Lt. Bill Lind of the 497th Bombardment Group taxied into his parking slot, pulled back the window next to his seat, and yelled down to his ground crew, “Hey, boys! Come over to this aircraft and smell Tokyo!”

It was 8:30 am, Chamorro Standard Time, March 10, 1945.

By the time the guns went silent, B-29s had dropped 104,000 tons of bombs on Japan, reducing to rubble 169 square miles in 66 cities. The bombing missions left homeless 9.2 million civilians, including 3.1 million in Tokyo.

Between June 1944 and August 1945, 402 B-29s were lost bombing Japan—147 of them to Japanese flak and fighters and 255 to engine fires and mechanical failures. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when combined, inflicted less damage than the great Tokyo firebomb raid.

It is the author’s opinion that the defeat of Japan without an invasion was caused by the overall B-29 campaign and not solely by the atomic bombings. Remarkably, the plan for the firebombing of Tokyo worked. U.S. casualties were painful but small in proportion to the magnitude of the mission’s success.

Fighting ended August 15, 1945. The formal surrender was inked aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, on Sunday, September 2, 1945.

Speaking to Allied and Japanese officers, General Douglas MacArthur, now the supreme Allied commander for the occupation of Japan, said, “The issues, involving divergent ideals and ideologies, have been determined on the battlefields of the world and hence are not for our discussion or debate.” He might have been referring to the great Tokyo firebomb mission.

The Japanese themselves tried to do something not dissimilar to the USA, with very little effect, sadly, though, killing six Americans.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fu-Go_balloon_bomb

An excellent introduction to the complete wasteland Japan had become by August 1945 can be found in the book “Medic”, by Brig. Gen. Crawford Sams, the Army doctor who oversaw public health during the postwar occupation.