By Joshua Shepherd

In the rolling fields on the south side of the Warrenton Turnpike, the men of the 5th New York of Colonel Gouverneur K. Warren’s brigade counted themselves among the luckiest troops in the Federal Army of Virginia. By late afternoon on August 30, 1862, Maj. Gen. John Pope’s newly constituted Army of Virginia had grappled with the Confederates for three straight days. But the Federals had little to show for their effort other than a line of battle littered with dead. The New Yorkers, positioned on the army’s left flank, had spent an uneventful day away from the main firing line.

It was a welcome respite. Stationed on a bald ridge fronted by timber, the regiment’s 500 Zouaves idled away the afternoon. Their brightly colored uniforms were inspired by those worn by French army units operating in the hot climate and rough terrain of North Africa. Each man wore white leggings, baggy red pants, a short blue jacket, and a tasseled red fez. Since no attack was expected in that sector, their officers had ordered arms stacked. Some dozed in the shade, while others played cards. Despite the unit’s relaxed stance, some of the men felt their role in the battle seemed too good to be true. One of these men was Private Alfred Davenport. He kept close watch on a stand of timber to the west. He had the unshakable impression that “some mischief was brewing.”

Shortly after 4 pm his fears proved all too true. A terrified group of Yankee skirmishers dashed up the ridge, frantically waving toward the trees. They shouted that the Confederates were coming and would be on top of them in a matter of minutes. The startled Zouaves scrambled to form up and face the threat just as the tree line erupted with a sheet of musketry that felled dozens of men in seconds. “The balls began to fly from the woods like hail,” thought Davenport. The regiment was assailed by the howling Rebels of the crack Texas Brigade. The Texans spearheaded the flank attack conceived by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, commander of the Confederate right wing, which aimed to destroy Pope’s army.

The seeds of the audacious attack had been laid on the Virginia Peninsula that spring. Since March 1862, Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had inched its way toward the Confederate capital at Richmond. McClellan had trumpeted great hope for his flanking move by water against Richmond. Almost as soon as he landed, though, he lost his nerve. He believed he was heavily outnumbered by the Confederates.

A portentous event occurred when Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commander General Joseph E. Johnston was seriously wounded during the fighting at Seven Pines on June 1. His replacement was General Robert E. Lee, a gifted engineer who previously had served as an adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis before being sent to northwestern Virginia in August 1861 to stem the Union advance east toward the Shenandoah Valley along the Staunton-Parkersburg Pike. After overseeing the defense of the coast of South Carolina and Georgia in late autumn, he returned to Richmond to continue advising Davis. When it became apparent Johnson would not return quickly to battlefield command, Davis put Lee in charge of the 55,000-strong Confederate field army. McClellan initially dismissed Lee as a Southern patrician who lacked experience commanding large armies. He soon had reason to reconsider his view of Lee.

Both Johnson and Lee preferred fighting McClellan in open terrain rather than from inside the Richmond defenses. A reconnaissance by Confederate cavalry under Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart revealed that Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s Union V Corps was deployed north of the Chickahominy River, while the rest of the Union army was south of the river. Lee counterattacked on June 26, concentrating his forces against Porter’s at Mechanicsville. In what became known as the Seven Days’ Battles, Lee repeatedly attacked McClellan until his back was against the James River at Malvern Hill. The Confederate counterattack removed the threat McClellan posed to Richmond and solidified Lee’s reputation as an aggressive commander.

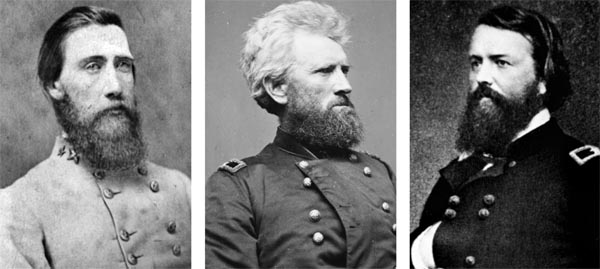

Exasperated by a glaring lack of aggression from his leading field commander, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln quickly considered his options for sacking McClellan. Lincoln appointed Pope to open a fresh offensive in northern Virginia. A graduate of West Point and a veteran of the Mexican War, Pope had shown tactical acumen by successfully capturing the Confederate outpost at Island No. 10 in the Mississippi River in April 1862, which earned him his second star. Lincoln believed that Pope had the aggressive nature to take the war to the enemy and boost the dwindling Union morale in the Virginia theater of operations. Pope successfully persuaded Lincoln to withdraw McClellan’s forces from the Virginia Peninsula and combine the two armies under Pope’s command.

Pope sparked a visceral reaction from friend and foe alike, but not the kind that Lincoln had in mind. He nettled everyone by bragging about his accomplishments in the West and making bombastic proclamations as he consolidated the scattered detachments that would constitute his newly created Army of Virginia. Pope’s machinations infuriated senior officers loyal to McClellan. On July 14, 1862, Pope issued an address to his new army that infuriated many of the officers he would be commanding.

“The strongest position a soldier should desire to occupy is one from which he can most easily advance against the enemy,” wrote Pope. “Let us study the probable lines of retreat of our opponents, and leave our own to take care of themselves. Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.” A number of officers voiced annoyance at the insolent tone of the proclamation. Porter, who was slated to serve under Pope, quipped that his new commander “has now written himself down as what the military world has long known, an ass.”

He also succeeded in raising the ire of Confederate commanders. Exasperated by what he considered a soft policy by the Union army toward Confederate civilians, Pope issued a string of orders intended to bring the harsh realities of war to the secessionists in Virginia. He ordered foraging on a mass scale, threatened to burn the homes of those who aided guerrillas, and demanded oaths of allegiance from male civilians. Lee called him a miscreant.

Although Pope expressed no interest in his lines of communication, Lee gave them careful scrutiny. Lee was informed on July 12 that Federal troops had moved on Culpeper and were within striking distance of the vital rail hub at Gordonsville where the Virginia Central Railroad met the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Gambling that McClellan would remain idle, Lee immediately dispatched two divisions to Gordonsville under the command of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, the hero of First Manassas. Far from content to assume the static defense of a rail depot, Jackson requested reinforcements. In response, Lee sent Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Light Division on July 27. Clearly seething at the Yankee crackdown on Virginia civilians, Lee told Jackson to teach the arrogant Pope a lesson he would not soon forget. “I want Pope to be suppressed,” Lee wrote.

With nearly half of Lee’s army at his disposal, Jackson had the means to begin fulfilling Lee’s order. As Jackson’s 24,000-strong column moved north from Orange toward Culpeper, it encountered Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks 12,000-strong II Corps in an exposed position at Cedar Run south of Culpeper. Jackson made contact on August 9 before all of his units were up, and for a while the battle hung in the balance as Jackson’s left flank crumbled in the face of a spirited attack by Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ division. But Jackson’s greater numbers compelled Banks to withdraw. Pope then sought to concentrate his scattered forces at Culpeper.

Realizing that McClellan was abandoning his position on the James River, Lee moved quickly against Pope’s army before it could be united with McClellan’s Army of the Potomac in northern Virginia. Lee issued orders on August 13 for Maj. Gen. James Longstreet to move north with his five divisions. With the Army of Northern Virginia consolidated in northern Virginia, it was Lee’s intention to strike Pope before he was reinforced. If that occurred, the Union army would number more than 100,000 men.

Although Pope’s 55,000 men sat squarely astride the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, he was also dangerously hemmed in between the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers where it was possible that he might become trapped. For that reason, he withdrew farther north. Lee issued orders on August 18 for his troops to cross the Rapidan and strike Pope. The Confederates moved slowly and did not cross until August 20 when Pope’s army was already safely on the north bank of the Rappahannock, having crossed the previous day.

That same day, Porter’s V corps of McClellan’s army began arriving at Aquia Creek, 10 miles north of Fredericksburg, with orders to march west to reinforce Pope. Two days later, Maj. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman’s III Corps arrived at Alexandria. Keenly aware that his long supply line was vulnerable to Confederate raiders, Pope sent a dispatch to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, general-in-chief of Union armies in Washington, to send a brigade to guard the bridge over Cedar Run near Catlett’s Station. Pope also requested that Halleck urge Heintzelman to march rapidly to his aid. Lastly, Pope ordered his III Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, to send cavalry regiments to guard Catlett’s Station.

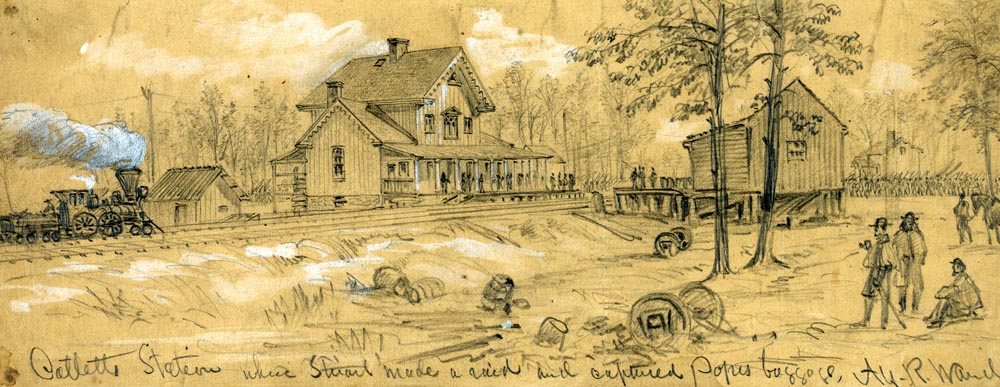

It was as if Pope had read Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s mind, for on the night of August 21 Stuart had suggested to Lee a raid against Catlett’s Station. Lee approved the idea in the hope that the raid might distract Pope long enough for Lee to get his army across the Rappahannock. The following morning, 1,500 of Stuart’s troopers splashed through the shallow waters of the upper Rappahannock at Waterloo Bridge in the rain. They clattered through Warrenton after dark and continued northeast to Catlett’s Station. The railroad station served as Pope’s headquarters, but he was not there at the time of the raid. Stuart’s troopers reached their objective late in the evening. In addition to nabbing several hundred prisoners, $350,000 in cash, and Pope’s dispatch book, Stuart also snatched a gratifying trophy in the form of Pope’s colorful dress uniform coat.

On August 24, Lee unveiled his plan for prying Pope from the Rappahannock line. Longstreet’s right wing would occupy Pope’s attention. Meanwhile, Jackson’s left wing would make a wide swing to the northwest using the Bull Run Mountains to screen its movements from Union eyes. Jackson would turn east through the mountains at Thoroughfare Gap in order to get behind Pope’s army. “It was a bold and beautiful play,” Lt. Col. Edward P. Alexander, Lee’s ordnance chief, wrote after the war. “For back at Manassas Junction 24 miles behind Pope’s line of battle were enormous stores and depots of Pope’s army.” It was an extremely risky plan. If Pope figured out that the two wings of Lee’s army were separated by as much as 50 miles he would be able to turn first against one wing and then against the other. Lee knew that neither Pope nor his troops were capable of great feats. For all his bombast, Pope was no match for Jackson in Lee’s mind. Besides, Pope’s army lacked cohesion and its units were, for the most part, poorly led.

Jackson, who thrived on the execution of such bold stratagems, had his men on the march well before sunrise on August 25. “Old Blue Light’s” foot cavalry made good time, capturing Manassas Junction two days later. Amid a festive atmosphere, the hungry Confederates ransacked bulging warehouses. Men in tattered uniforms greedily devoured all manner of delicacies, including lobsters, oranges, and, for a lucky few, whiskey.

Pope became convinced that evening that Jackson was vulnerable to attack. He therefore ordered his army, which by that time had been reinforced by two corps from McClellan, to converge on Manassas. Pope was so intent on catching Jackson that he neglected to consider that Longstreet might soon join him; however, McDowell covered for his superior by dispatching Brig. Gen. James Ricketts’ 5,000-man division to Gainesville where it could monitor Thoroughfare Gap.

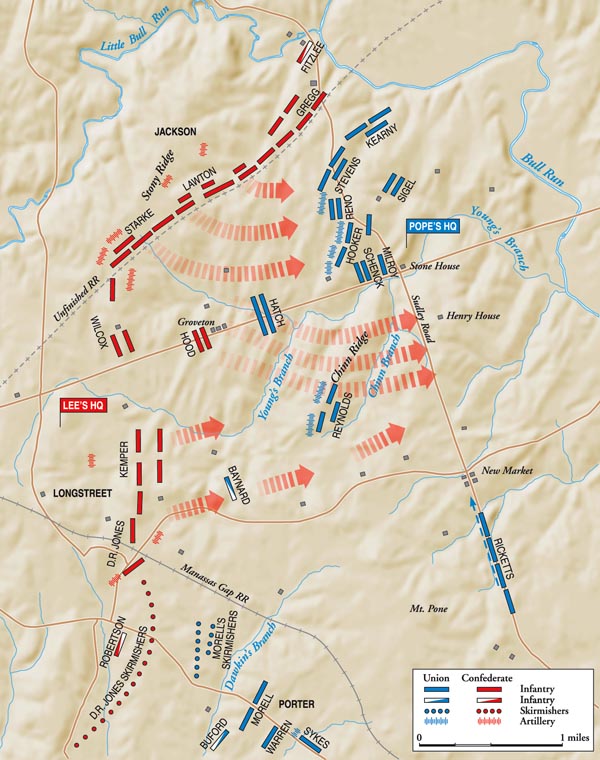

After pillaging Manassas Junction, Jackson had marched toward Centreville. On August 28 he deployed his troops in a concealed position along an unfinished railroad embankment on the battlefield of First Manassas. The unfinished railroad was part of an intended Independent Line of the Manassas Gap Railroad that would run from Gainesville to Alexandria, but it was never completed. From his position Jackson could strike Union troops marching east along the Warrenton Turnpike and link up with Longstreet’s wing, which was expected to soon pass through Thoroughfare Gap.

Throughout the afternoon Jackson watched as Federal troops marched east along Warrenton Turnpike oblivious to the Confederates a short distance away to the north. Jackson, who had watched them intently on horseback, rode back to where his troops were concealed in the woods. To lure Pope into attacking his strong position, Jackson issued orders for an attack just before 6 pm. “Bring out your men, gentlemen!” he said to his officers. A sharp firefight erupted in the gathering darkness on a farm leased by its owner to tenant John Brawner.

In a furious fight that lasted well into the darkness, Jackson’s wing engaged Brig. Gen. Rufus King’s division. King, who succumbed to an epileptic fit that day, had turned over command of his division to Brig. Gen. John Hatch. Before it was over, Jackson had committed elements of six brigades. The brunt of the fighting by Union forces was borne by Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s Black Hat Brigade. Although the action ended in a stalemate, Jackson had accomplished his objective.

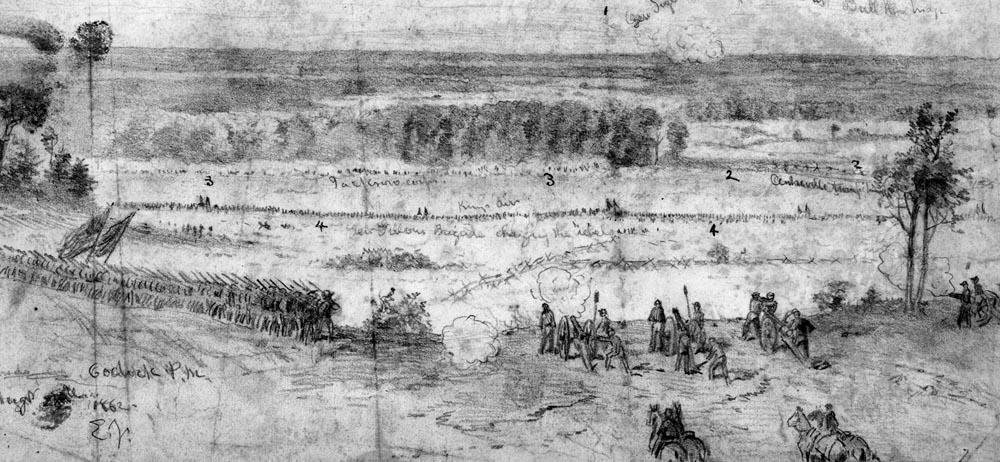

On the morning of August 29 Pope had 62,000 men on hand near the hamlet of Groveton with which to assail Jackson. Instead of striking both of his flanks at once in a deadly pincer move, Pope squandered his strength in a series of piecemeal attacks that allowed Jackson to fend off each of the uncoordinated assaults. Pope was unable to make any considerable headway despite having a significantly greater number of men than his wily opponent. The Federals came closest to a local success against Jackson’s left flank where Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg, waving his grandfather’s Revolutionary War sword, exhorted his South Carolinians to stand firm against the Yankees of hard-charging Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny’s division.

Having received regular reports from Jackson, Lee knew Jackson had the situation under control. He therefore allowed Longstreet to conduct his march at a relatively leisurely pace. McDowell’s foresight in placing Ricketts’ division at Gainesville came to naught. When Federal cavalry subsequently notified Ricketts that Longstreet’s column was approaching Thoroughfare Gap on the morning of August 28, the Union general failed to get his division in motion fast enough to block the Confederates. Colonel George T. Anderson’s Georgians secured the gap while the lead regiment of Colonel John Stiles’ brigade of Yankees was still a quarter mile away from it. Stiles attempted to drive them back, but his efforts were in vain.

Lee led the head of Longstreet’s column onto the field at 10 am on August 29. When he rode forward to reconnoiter the enemy, his cheek was grazed by a bullet fired by a Yankee sharpshooter. By 12:30 pm the bulk of Longstreet’s troops were deployed for battle. The junction of the two Confederate corps created a battle line three miles long. Longstreet’s line, which stretched for more than a mile, ran from the Warrenton Turnpike to the Manassas-Gainesville Road. Lee favored an immediate attack, but Longstreet requested and received more time to reconnoiter the enemy troop positions. To his disappointment, he found that the Union line extended well south of the Warrenton Turnpike, which meant his troops would encounter considerable resistance. For that reason, Longstreet requested even more time. Lee was skeptical, but Stuart returned from a separate reconnaissance to report that there was in fact a large threatening Federal force on the Manassas-Gainesville Road. The unknown Federal force was Porter’s V Corps. Fortunately for Longstreet, Porter was alarmed by the presence of a larger body of Confederates in his front, so he deliberately slowed his march.

At 9 that morning, Brig. Gen. John Buford, who commanded a brigade of Union cavalry acting in concert with Ricketts’ division, had informed McDowell that a formidable column of Confederate infantry had passed through Gainesville and turned onto the Warrenton Turnpike moving toward Pope’s army. McDowell thrust Buford’s dispatch into his pocket and forgot about it until 7 pm.

Pope arrived on the battlefield at 1 pm and established his headquarters in Groveton. Convinced that Longstreet would not arrive at least for another day, Pope had penned a highly confusing joint order to Porter and McDowell from Centreville at 10 am. The order directed both commanders to move forward and then quickly fall back. The order instructed Porter to work his corps around Jackson’s right, but then be prepared to retreat east of Bull Run at nightfall. Pope believed his order had been sufficient to deal with any threat that might develop to his left flank. Despite receiving four separate warnings from subordinates that a large body of Confederates was hovering on his left flank, Pope continued to believe that Jackson was disengaging.

At 5 pm Longstreet resolved to make a reconnaissance in force with seven of his 12 brigades. The move was designed in large part to give some of his best units a secure foothold next to the Union lines from which to resume their attack the following morning. Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s division would spearhead the attack, advancing astride the Warrenton Turnpike. Hood’s division consisted of his own Texas brigade as well as a mixed brigade led by Colonel Evander Law. Longstreet detailed Brig. Gen. Cadmus Willcox’s three brigades and two brigades of Brig. Gen. James Kemper’s division to support Hood. The attack began at 6:30 PM and continued until darkness made it too difficult to continue.

The attacking Rebels ran headlong into Hatch’s division. When Pope spied Confederate wagons moving west on the Warrenton Turnpike, he mistook what probably were ambulances removing the wounded for a phased retreat by Jackson’s troops. He could not have been more wrong. He told McDowell to attack the Confederates, and McDowell in turn ordered Hatch to pursue the supposedly retreating Rebels.

During the chaotic fighting that erupted in the gloaming, units became intermingled and shouts were heard often from troops on both sides to stop firing at their friends. After 90 minutes, the fighting stopped. The Confederates had fought their way to Groveton, and some of the Rebels had even reached the west slope of Chinn Ridge.

By the following morning, Pope had convinced himself that Jackson, beaten by the previous day’s fighting, was in full retreat. Pope ordered a pursuit of the supposedly panicked Confederates. Infuriated that the V Corps sat idle on the left flank, Pope ordered Porter to make an all-out attack on Jackson’s position, certain that one more frontal assault would shatter the Confederates for good.

At 3 pm, Porter’s troops went forward, swinging toward Jackson’s left. As the Federal columns neared the railroad embankment, even Confederates looked on with grudging admiration. When they opened fire, they unleashed a hail of musketry that felled hundreds in minutes. Pinned down by gunfire from the front, Union troops took a punishing fire from Confederate artillery. Colonel Stephen D. Lee (no relation to Robert E. Lee) commanded a battalion of artillery fielding 18 guns that enfiladed Porter’s left.

Federal troops briefly seized a section of the railroad embankment, but without support they had no choice but to fall back. After an hour of horrific fighting that left the field strewn with the dead and dying, the shattered V Corps retreated. McDowell, who exercised nominal control of the Federal left, abruptly ordered Brig. Gen. John Reynolds’ division to cross to the north side of the Warrenton Turnpike and support Porter. This left only about 2,200 Yankees south of the Warrenton Turnpike to contest Longstreet’s advance in that sector.

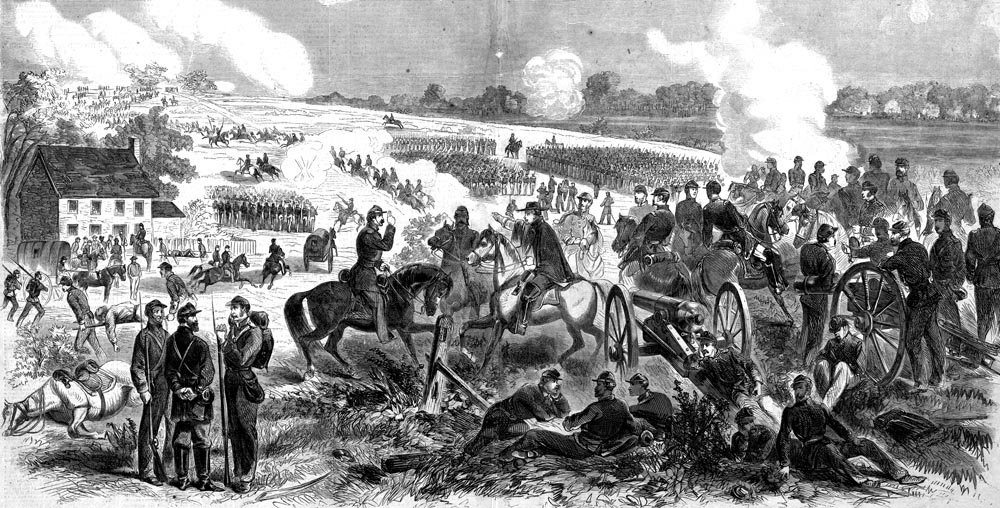

Lee, who recognized that the time had come to strike the Federals, immediately dispatched orders for Longstreet to send forward his entire wing. The attack, which had already been planned, was an imposing display of force, consisting of 28,000 men. The lead unit, the fierce shock troops of the Texas Brigade, would serve as a column of direction for the entire wing as it drove for the ultimate objective of the attack, the commanding eminence of Henry House Hill. From those heights, Longstreet would be in a position to control the Warrenton Turnpike, cut off the Federal line of retreat across Bull Run, and destroy the lion’s share of Pope’s army.

At 4 pm Longstreet unleashed his sledgehammer attack. As the Texans felt their way forward, they made contact with skirmishers from the 10th New York. The Confederates were moving fast. The New Yorkers gave the Rebels a single volley before darting off for the rear, where they gathered in front of the 500 men of the 5th New York. Hood’s men were snapping at their heels. The bulk of the 10th New York, which was disordered and demoralized following its short but bloody fight, fled the field.

As they did so the Zouaves of the 5th New York took the full wrath of Hood’s assault. His troops had succeeded in quickly working around the base of the hill and opened a murderous crossfire that felled scores of Federals in moments. The field was shrouded with a choking cloud of smoke, and the New Yorkers could barely make out the enemy that seemed to surround them. The Union troops could not escape the Confederates’ overwhelming fire. “Not only were men wounded or killed but they were riddled,” wrote Private Andrew Coats of the 5th New York.

In just minutes, what was left of the regiment broke apart. Hood’s men, smelling blood, swarmed across the hillside in close pursuit. In the mad dash for safety, dozens more were shot. When the regiment rallied on Chinn Ridge, it numbered just 60 men.

During the confusion of the fighting, not everyone had received orders to fall back. Still unlimbered at their original position, the six guns of Lieutenant Charles Hazlett’s Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery, were defiantly banging away at Hood’s troops. Seeing that the battery was about to be overrun, Private James Webb, in one of the war’s most memorable acts of individual valor, took off at the run to warn Hazlett’s gunners. Braving a gauntlet of enemy fire, Webb miraculously reached the battery and informed Hazlett that he was without infantry support. The unflappable artillerist led his battery off at the walk.

As the front line of Federal troops collapsed, the ugly reality of impending disaster dawned on McDowell. The obvious place to make a stand was Chinn Ridge, an imposing rise that, if manned in force, could contest the Confederate steamroller on its path toward Henry Hill. But before Union defenses could be patched together, McDowell had to make a desperate play for time. He frantically followed Reynolds’ division, which were the very troops that he had so recently ordered north of the Warrenton Pike. He directed Colonel Martin Hardin’s brigade, composed of four regiments, back to the fight.

Hardin’s troops, which were supported by Captain Mark Kerns’ battery, rushed into position on a small hill to the west of Chinn Ridge. When the Pennsylvanians formed up in two lines on the summit of the hill, Hood’s brigade was fast approaching. Kerns’ guns banged away at the Confederates, who briefly stalled on the banks of Young’s Branch.

The standoff was momentary. Without orders, some of the Confederates, electrified by the fight, spontaneously dashed up the hill. With Confederates lapping around his flanks, Hardin rushed forward his second line of infantry, but the weight of numbers told. Collapsing under the pressure of the Rebel onslaught, Hardin’s infantry broke for the rear. Kerns’ gunners did not last much longer. Streaming for the safety of Chinn Ridge, the artillerists abandoned their guns and their captain.

Kerns was made of stern material. Left alone on the field, he single-handedly attempted to man the six guns of his battery. Some of the Confederates began shouting for their comrades to hold their fire for the Yankee artilleryman was far too brave to kill. But when Kerns readied to fire a load of canister, chivalric sentiments gave way to sheer survival, and he was shot down.

With the position cleared of Federals, Hood set his sights on the commanding heights of Chinn Ridge. The ridge was only 300 yards away beyond a steep ravine, but a fresh brigade of Federals, as well as the frowning guns of an enemy battery, was clearly visible along the summit. Wasting little time, Hood ordered his men forward, first seeking cover in the ravine, and then angling to the right for a belt of timber that could help shield his troops from Federal artillery. During the confusion of the advance, Lt. Col. Benjamin Carter’s 4th Texas fell back to Young’s Branch. This left Hood’s brigade with just three regiments to assault the daunting ridge.

Fortunately, he would have help. His immediate supporting brigade, the South Carolinians of Colonel Nathan “Shanks” Evans, arrived in front of Chinn Ridge but edged ever farther to the right. Lashed by massed Federal batteries on Dogan Ridge to the north, the Carolinians continued the mad push toward the right until Evans lost tactical control of his brigade. His regiments would go into action piecemeal.

Atop Chinn Ridge, Colonel Nathaniel McLean’s brigade of 1,200 Ohioans, which constituted the 2nd Brigade of Brig. Gen. Robert Schenck’s division, anxiously awaited the Confederate assault. For his actions slowing the Confederate advance on August 30, McLean would be promoted to brigadier general the following month.

From the front, McLean was assailed by the 17th and 18th South Carolina Regiments of Evans’ brigade. The Confederates came on gamely but were badly mauled in their ascent of the ridge. Artillery fire, paired with McLean’s musketry, tore great gaps in the ranks of the Palmetto Staters. In the intense fighting that unfolded on the ridge, Colonels John Means and James Gadberry, of the 17th and 18th South Carolina, respectively, were slain. When Evans’ attack sputtered, Colonel Jerome Robertson’s 5th Texas entered the action. The Texans tried to swing around McLean’s flank, but failed to dislodge them. McLean’s brigade held its ground.

McLean caught sight of a massive body of troops headed for his left. The colonel hoped the troops were Union reinforcements. Unfortunately for the Yankees on Chinn Ridge, they were the four brigades of Brig. Gen. James Kemper’s division. Colonel Montgomery Corse sensed the Federals’ vulnerability. His troops swept north along the ridge. The Buckeyes, who were deployed behind a fence, waited until the Confederates were within 50 yards, and then they rose up and unleashed a terrific volley. The Virginians reeled under the heavy blow.

The volley “struck the long line like an electric shock,” wrote Private Alexander Hunter of the 17th Virginia. But the officers surged ahead cheering on the men…. The left of our brigade struck the enemy’s right and doubled it up. In a moment the blue line quivered and went to pieces.”

Time was running out for McLean’s stubborn troops. A renewed Confederate push, which was supported by artillery, ultimately broke the Ohioans’ line. The Confederates had shot down 400 of the Buckeyes in just 30 minutes. Nevertheless, McLean bought time for another Union line to be formed behind him.

As the survivors fled for the rear, reinforcements arrived on the scene in the form of Brig. Gen. Zealous Tower’s brigade of Ricketts’ division, as well as five guns from Captain George Leppien’s 5th Maine Battery. Tower hastily deployed his four regiments across Chinn Ridge where they came under heavy attack by the advancing Rebels. Corse’s Virginians, augmented by portions of Hood’s and Evans’ brigades, lapped around both of Tower’s flanks. The Confederate crossfire shredded Tower’s brigade. The 88th Pennsylvania on Tower’s left broke under the pressure, its men streaming to the rear in confusion.

As Tower’s position crumbled, Colonel Frederick Skinner of the 1st Virginia spurred his mount ahead of his men. He thundered into the midst of the Maine artillerymen. When one of the Federals attempted to fire a gun, Skinner swung his sword, a ponderous old French dragoon saber, in a wide arc that severed the Yankee’s head. Skinner cut down another gunner, but was assailed by a third, who discharged his pistol into Skinner’s face. The shot narrowly missed killing him, slicing off a bit of his earlobe. Although Skinner cut the man down, he was shot in the arm and ribcage.

Both sides funneled more men into the fight, but the Federals, caught in the vicious vice of a massive Confederate assault and entirely outflanked, got the worst of it. A frantic McDowell ordered two more brigades onto Chinn Ridge, where Kemper’s troops overwhelmed them. The Federals fought bravely but suffered for it.

“Our boys dropped like tenpins,” wrote Private George Paine of the 13th Massachusetts. He recalled seeing a soldier drop to the ground in front of him. “I heard the bullets chug into his body; it seemed half a dozen struck him. I shall never forget the look on his face as he turned over and died,” recalled Paine.

The momentum was clearly with the Confederates. At 6 pm, an hour before dark, Longstreet’s Confederates had pried loose the last of the Federal defenders on Chinn Ridge. In 90 minutes of furious fighting, the Confederates had overwhelmed the troops directed by McDowell to hold Chinn Ridge. But the Federals’ costly defense of the ridge had furnished Pope with precious time in which to bolster the defenses of Henry Hill. If his troops could fight a successful rearguard action on Henry Hill, he would be able to hold the Stone Bridge over Bull Run long enough for his troops to cross to safety.

Oddly enough, the troops that Pope ordered to Henry Hill were the two remaining brigades of John Reynolds’ division. These were the same troops whose redeployment from the left flank, ordered by McDowell, had led to disaster. As Reynolds’ men formed up on the crest of Henry Hill, Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy’s Independent Brigade formed on their left and Lt. Col. William Chapman’s crack brigade of U.S. Regulars formed on Milroy’s left. The strong Union line was supported up multiple artillery batteries.

Lee and Longstreet would give them little time to prepare. Jackson’s wing began a tardy push against the Federal right. About the same time, Brig. Gen. David R. Jones’s three brigades of Georgians and South Carolinians from Longstreet’s wing formed up to assault the Union troops on Henry Hill. Jones’s troops surged up the slope of Henry Hill into the teeth of the Union musketry and artillery.

Charging to within 50 yards of the Union line, the Georgians and South Carolinians sought cover and returned fire. The Federals, who were fully aware that the fate of the battle hinged on the possession of Henry Hill, stood their ground. The Confederates continued feeding more troops into the assault on Henry Hill.

Longstreet had placed Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s division behind his other four divisions so that Anderson’s troops might deliver the coup-de-grace to the routed Federal army. Anderson’s three brigades were led by Brigadiers Lewis Armistead, William Mahone, and Ambrose Wright. These troops moved into position for a fresh assault. Mahone’s four regiments of Virginians overlapped Chapman’s flank. A savage firefight unfolded on the extreme Union left between the Regulars and the fresh Rebel troops.

The Regulars paid horribly for their stand. With his ranks rapidly thinning, Chapman was forced to withdraw his remaining troops. Moving up to relieve them was Colonel Robert Buchanan’s brigade of U.S. Regulars. In the center of the Henry Hill line, Milroy broke down. He babbled incomprehensibly for reinforcements. When the apoplectic brigadier attempted to commandeer two of Buchanan’s regiments, the defiant colonel told him to go away.

Such steady nerves began to turn the tide of the battle. Pope succeeded in funneling further reinforcements toward Henry Hill, and Anderson’s Confederate division, exhausted after its hurried march to the hill, failed to press the attack. As dusk fell, the last-ditch Union line on Henry Hill began to stabilize. Sporadic fighting would continue into the darkness, but the Federal Army of Virginia, though badly mauled by Longstreet’s massive attack, had narrowly escaped destruction. Pope issued orders for a retreat to Centreville where the exhausted Union troops immediately entrenched.

The Federal army had been soundly defeated but was able to retreat in good order. Ultimately, Pope was able to save himself from total disgrace, but it had taken the blood of brave men to do so. The human cost of the fierce fighting was simply staggering. Pope lost nearly 14,500 men. In comparison, the Confederates suffered just 7,200 casualties.

The results of the defeat were equally devastating to the Northern war effort. Pope, not surprisingly, was edged out of his command on September 2, and an exultant McClellan resumed command of a reunited Army of the Potomac. Pope’s inept leadership had set the stage for a Confederate invasion of the North.

Officials of the Lincoln administration voiced their outrage at the second debacle suffered by the Union Army on the plains of Manassas. “Never before was there such a grand army, composed of truly excellent materials, and yet, so poorly commanded,” said Attorney General Edward Bates. One Rebel offered his own homespun assessment. “We whipped the Yankees worse this time than they ever was whipped before,” said Jefferson Wilson of the 16th Mississippi.