By Al Hemingway

By the middle of July 1403, a series of seemingly inevitable events had led two armies to a field near the small and hitherto unheralded village of Shrewsbury in Shropshire, approximately 150 miles northwest of London. The tiny hamlet was important for several reasons. It was the main town on the road that led south to the capital, it was one of the few spots where the Severn River could be forded, and it could be utilized as a supply base for either army. Whoever managed to seize and hold Shrewsbury might very well rule England.

Plotting in Exile

The political turmoil leading up to the battle had commenced during the reign of King Richard II, who had banished his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, from England for a period of six years beginning in 1398. Henry was the son of John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, who in turn was the son of King Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. A stocky man of average height, with a closely trimmed auburn beard, Henry was known around court as something of an intellectual. He openly, if ill-advisedly, claimed that he had more right to the throne than his unpredictable and despotic cousin, Richard. When he was cast out of England for his views, Henry traveled to France, where he was greeted warmly by King Charles VI and other French nobility.

Within a few months, Henry received the devastating news that his father had died. At the same time, he learned that Richard had disowned him and had given all the family’s land and money to other nobles who more strongly supported the throne. The king ordered that Henry’s exile be changed from six years to life. Stunned by Richard’s actions, Henry immediately began plotting his return to England to seize power from his cousin. His spies informed him that the country was seething with discontent. That was not entirely true. Although they loathed the effete and possibly homosexual Richard, many of the English peasants remained loyal to the crown itself, although they feared that the king’s volatile behavior might result in further harm to the stability of their homes and farms.

Boiling with anger over his treatment at the king’s hands, Henry secretly returned to England in the summer of 1399 while Richard was off campaigning in Ireland. Henry quickly aligned himself with Thomas Arundel, who had also incurred Richard’s anger and been removed as Archbishop of Canterbury. Forced into exile, Arundel journeyed to Rome and received an audience with Pope Boniface IX, during which he requested that the pope intercede on his behalf. Boniface sympathized with Arundel’s plight and wrote to Richard—one head of state to another—asking that he reconsider and reinstate Arundel as archbishop. Richard’s rude reply infuriated the pope, and soon Arundel and Henry were scheming together to overthrow the English monarch.

Henry wanted to raise an army and overthrow the king by force. However, the politically attuned Arundel persuaded him that such a strategy would be unwise. If Richard was forced to step down by military means, all property would immediately become Henry’s—the very thing most feared by the commoners. By doing so, Henry’s support among the populace would be greatly diminished.

The Abdication of Richard II

Upon his return from Ireland, Richard was taken prisoner in Wales and transported to London. Throngs of people lined the roads and tossed garbage at him as he rode by. The unpopular king had to be closely guarded because people demanded that he be put to death. Henry, a wise politician, resisted for a time, fearing that such an execution would prove detrimental to his own fortunes as the next king of England.

Richard was imprisoned in the infamous Tower of London to await his fate. A document detailing his shortcomings as king, undoubtedly authored by Arundel, was presented to Richard by Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland, and Ralph Neville, the Earl of Westmoreland, for his signature. Fearing for his life, the king had no choice but to sign the paper. On September 29, 1399, Henry read the treatise aloud before Parliament, outlining his cousin’s gross inadequacies as the country’s ruler. After his abdication, Richard was confined to Pontefract Castle, where he died in February 1400. The official cause of death was listed as starvation; whether it was self-imposed or initiated by Henry remains uncertain. Whatever the case, Bolingbroke was soon crowned King Henry IV. To this day, historians argue the legality of the succession. Legal or not, Henry was now the new monarch of England. His tenure as king, he would soon discover, would not be an easy one.

To show his gratitude to the Percy clan of Northumberland, the newly appointed king showered them with land and honors. He named Henry Percy, known as Harry Hotspur by the Scots because of his speed in battle, warden of the Eastern Marches and justiciar of North Wales. Percy was also designated constable of Berwick, Roxburgh, Bamburgh, Chester, Flint, and Carnarvon. The powerful Percys were the controlling family in northeastern England and were cousins to Henry Bolingbroke. They had rallied to his aid when Richard confiscated all his property and exiled him to France. But there was an ulterior motive for the Percy family’s assistance to Henry. Hotspur’s father, also named Henry, knew full well that his son had an equal claim to the throne because of his blood line. Despite the tributes bestowed upon them, a serious rift developed between the Percys and the House of Lancaster.

The precarious situation in always troublesome Wales was unraveling quickly. Edmund Mortimer had been captured by the Welsh patriot Owen Glendower at the Battle of Pilleth in 1402. Hotspur was enraged that Henry would not ransom him. Hotspur was related to the Mortimers, another family with ancestral claims to the throne. A romance had developed between Mortimer and Glendower’s daughter, and they eventually married. Meanwhile, Hotspur was married to Mortimer’s sister, Elizabeth. These unions, to be sure, did not escape Henry’s attention. Being an astute politician, he realized from the outset that he needed the cooperation of his influential neighbors to the north.

The king’s reason for not ransoming Mortimer was simple: he believed that it would finance Glendower’s ongoing campaign in Wales. The Welsh rebel was enjoying considerable success by using guerrilla tactics against the English. Hotspur, however, had another theory. He believed the king realized that Mortimer’s nephew, the Earl of March, had more right to the throne than Henry himself. Soon, Hotspur would use the same guerrilla tactics against Henry.

Henry Hotspur’s War with the Scotts

The king had given the Percys large swaths of countryside in Scotland—the only problem was that the land was still controlled by the Scots. Warfare along the Scottish border was savage and bloody. Fearing an invasion of Northumberland by Scottish forces, Hotspur petitioned the king for funds to fortify Carlisle and Berwick Castles. Henry ignored his request. The Scots did manage to capture Conway Castle but, after a month-long siege, Hotspur drove the invaders back from the structure. Once again Hotspur wrote to the king, this time requesting back pay for his army. Frustrated, Hotspur advised Henry, “Remember how I have repeatedly applied for payment of the king’s soldiers who are in such distress as they can no longer endure owing to the lack of money. I therefore implore you to order that they be paid. If better means cannot be found, I shall have you go in person to claim payment, to the neglect of other duties.” As before, Henry ignored the plea.

Disgusted, Hotspur resigned the offices that Henry had granted him and returned home to help his father negotiate a separate peace with the Scots. In June 1402, when such talks failed, the Scots slipped back across the border and began to plunder and rape. To avenge these new outrages, Hotspur’s men ambushed Scottish forces at Nesbitt Moor and won a stunning victory against the marauders. Thirsting for revenge, the Earl of Douglas enlisted 12,000 soldiers and knights and invaded England that August. Driving deep into English territory, they laid waste to the countryside, killing hundreds of English citizens and seizing anything of value. Slowed by his men’s wagonloads of stolen goods, Douglas decided the time was right to make a dash back across the border.

Unfortunately for the Scots, Hotspur, assisted by Lord Dunbar, the Earl of March, who had been banished by Douglas a year earlier, intercepted Douglas’s army at Homildon Hill, six miles north of Wooler, in Northumberland. Again, Hotspur won a decisive victory as English bowmen inflicted hundreds of casualties while Hotspur’s foot soldiers sat out the battle in relative safety. In the end, five earls, including Douglas, were taken prisoner by the Percys.

“Not Here, but in the Field!”

Elated by the news, the king immediately sent word that none of the prisoners was to be ransomed or traded for other captives held by the Scots. Henry felt that holding onto the Scottish monarchy might bring some stability to the border and encourage a cessation of hostilities between the two countries. Deep down, however, Henry knew full well that this course of action contradicted established custom and would infuriate the aptly named Hotspur once again.

Henry’s edict soon garnered the stormy response he anticipated. Hotspur was incensed. When Henry ordered his prisoners transported to London, Hotspur sent all the earls with the notable exception of Douglas. Now it was Henry’s turn to fume, and he wasted no time in dispatching riders ordering Hotspur to appear before him. When he reached London, Hotspur met immediately with the king. The conversation quickly became heated, with Hotspur demanding that Mortimer be released and the king ordering Douglas to be brought before him. Witnesses to the bitter exchange reported that Henry had called Hotspur a “traitor” and struck him in the face. The enraged nobleman did not strike back, but left the room crying, “Not here, but in the field!” The tension between the two houses had finally reached the breaking point—war was inevitable.

Raising a Rebel Army

Hotspur returned north and informed his father of what had happened The Percys knew that they had no time to waste; rumor had it that a 100,000-man Scottish force under the leadership of the Duke of Albany was preparing to strike at Cocklaw Castle, which had been under siege by the Percys. Before his departure, Hotspur’s wife, Elizabeth Mortimer, gave birth to a son. The child further cemented the relationship between the Percys and the Mortimers. Even Henry realized that Hotspur’s son “had nearer right to the crown than his own offspring.” Fearing for the safety of his family, Hotspur sent them to a safer dwelling and placed them under heavy guard.

Leaving his father in the north to counter the continuing threat from Scotland, Hotspur, together with the captured earls from the Battle of Homildon Hill and his uncle, Thomas Percy, set out for Cheshire County. The inhabitants of Cheshire, located in northwestern England, were still strong supporters of Richard. It was there, and in communities strung along the border with Wales, that Hotspur hoped to raise an army to defeat Henry. Some of the greatest archers in England resided in Cheshire. The always apprehensive Richard had recruited them to serve as his private bodyguards. Many of the archers, in open defiance of the king, still wore the White Hart, Richard’s personal emblem.

Soon supporters arrived from Shropshire, Flintshire, Herefordshire, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Hotspur’s own Northumberland to fill the ranks of the rebel force. The size of the army grew to between 5,000 and 7,000 men. At the core of Hotspur’s band of soldiers were the famed Cheshire archers. He hoped and believed that their expertise with the longbow would be the decisive factor in a pitched battle with Henry.

Another ally on whom Hotspur was counting for troops was Owen Glendower, the famed Welsh guerrilla fighter who had repeatedly eluded Henry’s men. It was unlikely that Glendower would want to meet the English army in open warfare. His lightly equipped force specialized in hit-and-run tactics to keep the more heavily armed royal soldiers off balance. Nevertheless, at the beginning of July, Glendower struck the English in southwest Wales to divert attention and allow Hotspur time to gather and maneuver his own men.

The Armies Assemble at Shrewsbury

It was Hotspur’s aim to link up with Glendower and proceed to the town of Shrewsbury to defeat a small royalist garrison commanded by Henry’s 16-year-old son, also named Henry, the Prince of Wales. After this was accomplished, Hotspur would reorganize and advance in force to crush the king.

Hotspur’s ranks included many noblemen, including Sir John Browne, a veteran of the Spanish and French campaigns who had served with Hotspur in Wales. Sir Richard Vernon and Sir John Massey also joined him, bringing with them other members of the noble families and local villagers. Hotspur received another boost when Thomas Percy, his uncle, the Earl of Worcester, arrived with nearly 1,000 knights and archers. Percy had been one of King Henry’s favorites because of his knowledge of military affairs. He previously had been stationed with Prince Henry at Shrewsbury, and his desertion had greatly depleted the young prince’s force.

To help rally his troops, Hotspur told the men that Richard was still alive. The outrageous lie had the desired effect—more men rallied to the Percy cause. At the village of Sandiway, however, Hotspur finally informed his men that Richard was dead, the victim of murder. Furthermore, he charged, King Henry had reneged on his promises not to assume the throne. The time had arrived to oust him from power. On July 17, Hotspur and his uncle delivered a formal decree stating that the Earl of March was the lawful heir to the throne of England. They announced that Henry should be ousted and that they should fill the “title of joint protectors of the Commonwealth.” Again they accused Henry of violating his promise not to pursue the title of king and arraigned him for having a hand in the gentle Richard’s suspicious death.

While Hotspur and his cronies were aligning themselves for battle, King Henry was not idle. Receiving reports that Hotspur was raising an army against him, the king decided to move quickly for fear that Hotspur would merge his force with Owen Glendower’s. Postponing a military campaign aimed at the Welsh rebels, Henry sent his 25,000-man army toward Shrewsbury to assist his embattled son. Covering 60 miles in three days, Henry arrived at Shrewsbury on July 20, just before Hotspur reached the field, impeding the rebel advance and thwarting Hotspur’s plan to link up with the Welsh troops.

Hotspur was shocked when he realized that the royal army had reached Shrewsbury first. Henry had done the impossible. Somehow he had conveyed a clumsy, unwieldy, slow-moving army of 25,000 men, with all their baggage, supplies, and camp followers, a quarter of the way across England in less than three days. Now it was not the Prince of Wales and a hapless skeleton force facing the rebels, but the king of England with all his host who waited to confront them at Shrewsbury.

Vastly outnumbered, Hotspur had no choice but to go on the defensive, as he had done successfully at Homildon Hill. Scouting the area, Hotspur selected a 300-foot-high ridge line just south of the hamlet of Berwick, near the Severn River. Known locally as Hateley Field, the ground constituted two marshy ponds and a large field of pea vines in the front of the rebel army’s position, making it extremely difficult for Henry’s men to maneuver. To further obstruct the king’s advance up the ridge to their position, the rebels twisted the pea vines together to make rudimentary earthworks.

Brother Against Brother, Friend Against Friend

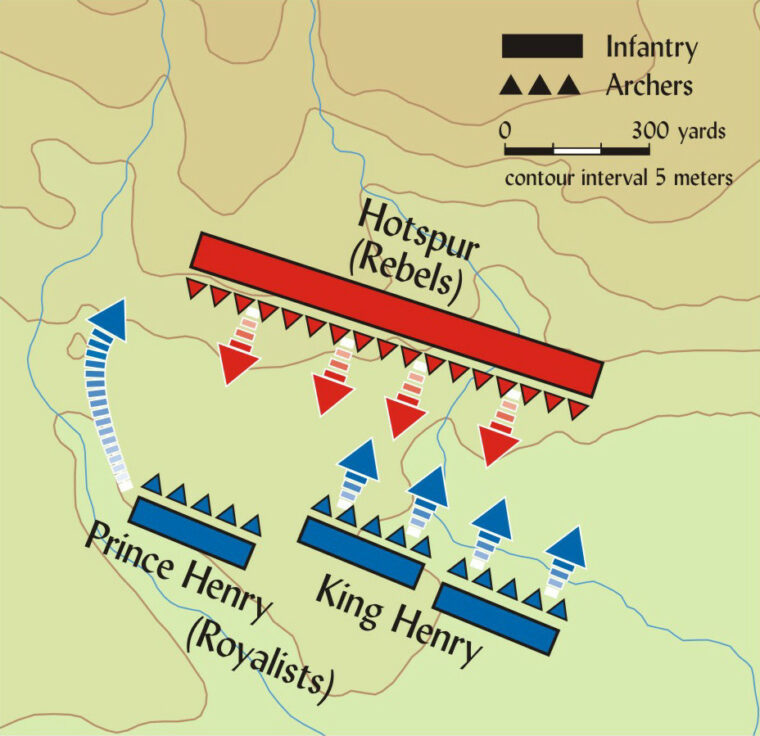

On the morning of July 21, Henry’s forces moved toward the rebel army’s position. At a distance of 500 yards, the royalists halted their movement, carefully out of range of the archers. The royal forces were divided into three distinct groups: King Henry, with the savvy George Dunbar, commanded the center. On their right was the Earl of Stafford’s division, and on the left was the smaller garrison at Shrewsbury, led by Henry’s son, the Prince of Wales.

The rebel side was also formed into three units. Hotspur headed the center of the line, while the Earl of Worcester and Sir George Browne were entrusted with the other two wings. The movement by the opposing armies took hours and did not end until early afternoon. Although both sides seemed girded to fight, nothing happened. The combat would pit brother against brother and friend against friend, and no one seemed particularly anxious to trigger hostilities. Realizing this, several monks from Shrewsbury and Haughmond rode out on their donkeys in an attempt to negotiate a last-minute peace settlement.

Not trusting Henry, Hotspur instructed the Earl of Worcester to go on his behalf and meet with the king. Riding into the royalist lines, Worcester explained to Henry the rebels’ demands, which at any rate had been put forth a few days before in their haughty proclamation. Of course, the king had no intention of submitting to such unreasonable terms. He countered with his own proposals, stating that if they laid down their arms he would be lenient with the rebels. The bickering continued for some time until both men knew that it was fruitless to continue. Some of the rebels, however, thought that the king’s offer was eminently reasonable and abruptly deserted Hotspur to join him.

Realizing that the peace talks had disintegrated, Hotspur instructed Worcester to end the discussion. He feared that Henry was stalling for time while waiting for additional soldiers to arrive to bolster his force. As Worcester prepared to leave, he yelled back to Henry, “We cannot trust you!” Looking coolly at his former ally, Henry replied, “On you must rest the blood shed this day.”

A Bad Omen for Hotspur

Worcester wasted no time in galloping back to Hotspur to relay the news. Realizing that a battle could no longer be avoided, Hotspur deployed his forces and called for his staunch, crescent-handled weapon. Told that he had left the sword behind at Berwick, the village where he had slept the night before, the prince groaned and cried when he received the news. The superstitious Hotspur had been warned of just such an omen some years before by a soothsayer who had predicted that he would go into battle without his favorite saber and be killed.

With no time now to brood about supernatural prophecies, Hotspur eyed the field before him as the royalist army began their advance. With the cry of “En avent banner!” the royal forces raced forward to engage the rebels. As the soldiers struggled in the mass of contorted pea vines, the attack lost momentum. While men in cumbersome suits of armor and chain mail tried to loosen themselves from their entanglements, the Cheshire archers let loose a broadside. Thousands of arrows rained down upon Henry’s men, one observer said, like “a thick cloud that blotted out the sun.” The royal vanguard dropped “like apples fallen in the autumn when stirred by the south west wind.” The king’s archers attempted to provide support for the beleaguered soldiers, but they did not have the range. Terrified by the astonishing accuracy of Hotspur’s bowmen, Henry’s men had no choice but to withdraw and reorganize.

As the king’s men ran to the rear to get out of range of the deadly missiles, the Earl of Stafford was killed. At the same time, the young Prince of Wales was struck by an arrow in the face, but he refused to leave the battlefield and continued to shout encouragement to his men.

“Esperance! Esperance, Percy!”

From his vantage point, Hotspur was overjoyed at the way the battle was unfolding. He realized, however, that he could not gain a decisive victory over King Henry while his army occupied a defensive position. Knowing full well that he was still greatly outnumbered, Hotspur also knew that he must attack. With the royalists retreating in confusion, he calculated that now would be the ideal time to do so. Ironically, Hotspur had wanted to use the same strategy at Homildon Hill, but the Lord Dunbar, who was now on the opposing side, had advised against it. This time the impetuous prince did not have the advantage of Dunbar’s wise counsel, and he recklessly proceeded with his assault.

Although Hotspur’s rash move might be viewed as foolish, some historians have suggested that another factor may have played a pivotal role as well: the Cheshire longbowmen may have used the majority of their arrows to break up the initial charge. If Henry’s men regrouped and renewed their assault, they could overrun the rebel lines and achieve a victory. The impulsive Hotspur may have realized this and set out to crush Henry before the king could catch his breath.

With the cries of “Esperance! Esperance, Percy!” filling the hot, humid air, the rebel army left its defensive positions and surged down at the enemy. Leading the charge with approximately 100 mounted knights from their household troops were Hotspur and the Earl of Douglas. Their thundering charge caught the royalists completely off guard and they “made an alley in the midst of the army.”

Riding through the gauntlet, Hotspur’s knights slashed and cut their way through the swirling mass of bewildered soldiers that surrounded them. As the remainder of the rebels reached the melee, vicious hand-to-hand combat began. The clash of swords and broad axes was deafening. Men’s limbs were lopped off with shocking ease and pools of blood soaked the ground.

In addition to swords, a wide assortment of weapons was utilized by both armies. The cavalry used a “morning star,” which resembled a mace, a spiked wooden ball on a handle that could smash the heads of the enemy. Infantry carried morning stars mounted on longer handles so that they could wield them like a modern baseball bat. Foot soldiers were armed with pikes, razor-sharp curved blades affixed to the end of wooden poles. A large variety of battleaxes and spears were carried by the soldiers as well.

The Prophecy Fulfilled

As the fighting swirled in the middle of the field, Hotspur’s men routed Stafford’s disoriented division, weakening the king even more. Meanwhile, Hotspur hacked his way through to reach Henry’s personal standard-bearer and confront Henry in a fight to the death. When Hotspur’s men killed Henry, a shout of joy swelled in the rebel ranks. Unbeknownst to them, they had killed an imposter. The wily Dunbar had had the king taken to the rear for his safety. Several look-alike knights dressed in the king’s uniform were impersonating him on the battlefield.

It was Hotspur, not Henry, who would be killed. Accounts differ on the manner of his death, but the most common version had him lifting the visor of his helmet to gain a better view of the battlefield and get a much-needed breath of fresh air. At that exact instant an arrow pierced his face. When word spread that Hotspur had been slain, the impetus of the rebel attack sputtered. Before the rebels could withdraw from the field, the left wing, commanded by the Prince of Wales, fell upon them with a vengeance. With the arrival of the king’s reinforcements, the insurgents broke and fled. Many of them were killed by King Henry’s soldiers, who raced after them and cut them down without mercy. Even those incapacitated by their wounds were butchered where they lay—no quarter was given. The fighting continued until nightfall. The entire battle, from start to finish, had lasted only three hours.

Putting Down the Rebellion

As the sun rose the following day, townspeople were horrified by the sights that awaited them. Even the most hardened person was sickened by the wholesale slaughter that had occurred outside Shrewsbury. For three miles, mutilated corpses were strewn over the battlefield. One chronicler later penned, “Those who were present said they never saw or read in the records of Christian times of so furious a battle in so short a time or of larger casualties than happened here.”

Approximately 1,600 soldiers and knights were killed outright, with many others dying later from their wounds. The majority of those slain were royalist soldiers, most of whom had been killed by the deadly barrages from the rebel archers. Henry had a mass grave dug to dispose of the bodies. Three years after the battle, he ordered that the Church of St. Mary Magdalene be constructed on the site to commemorate those who had died there.

When Henry found the body of Hotspur, he supposedly cried. He had the rebel leader buried in Whitechurch, which was in close proximity to the battlefield. However, when rumors circulated that Hotspur had survived, the king had his remains exhumed and strung between two millstones just outside the gates of Shrewsbury for everyone to view. Then the corpse was beheaded and quartered, with the parts scattered throughout the country. Hotspur’s gory head was put on display in York. When his father was summoned to receive his pardon from Henry, he was no doubt horrified at the sight of his son’s head, publicly displayed for all to see. This did not deter the Earl of Northumberland from continuing to scheme against Henry until his own death in battle at Bramham Moor in 1408.

Henry dealt severely with Hotspur’s erstwhile allies. The Earl of Worcester, Sir Richard Vernon, and Sir Richard Venable were hanged, beheaded, and quartered as traitors. The Earl of Douglas, who fell and shattered his kneecap while trying to escape, was ransomed instead of executed. Many of the surviving common soldiers were spared. Cheshire fighting men, in particular, were essential to the continuing war in Wales, and Henry craftily sought to win their allegiance by gentler means.

A Bloody Future for England

With the defeat of the rebel army at Shrewsbury, the Percy clan’s influence was broken for good. Now Henry could consolidate his forces and concentrate his efforts in quashing the Welsh rebellion. In 1409, with the capture of Harlech Castle, the English were victorious and Owen Glendower disappeared into the countryside and passed away quietly a few years later. King Henry’s health soon declined as well, no doubt ruined by his spending so much time in the field putting down the many revolts that preoccupied much of his reign. In 1413, just a decade after his stunning victory at Shrewsbury, Henry died and his son, the Prince of Wales, ascended to the throne as the soon to be legendary Henry V.

Little did Henry realize that his overthrow of the ineffectual Richard II would anger so many and plunge England into a bloody civil war. It would flare up again a half century later in what would become known as the War of the Roses, when members of the House of York challenged the continuing claim to the throne of Henry’s descendants in the House of Lancaster. For the next three decades armies from both sides would fight a series of pitched battles that drained the country of its manpower, eroded English power in France, and signaled the end of the medieval era and the beginning of the Renaissance.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments