By Joshua Shepherd

At midnight of June 6, 1944, a trio of Halifax bombers, each towing a Horsa glider, roared above the black waters of the English Channel. Aboard each of the gliders, 15 heavily armed British infantrymen quieted their nerves by singing lively drinking songs. Despite the lighthearted diversion, the tension aboard the gliders was palpable. Private Harry Clark recalled that this flight was far different from his many training exercises. “I think people began to realize what we were heading for,” recalled Clark, “We were now faced with a situation, there was no going back.”

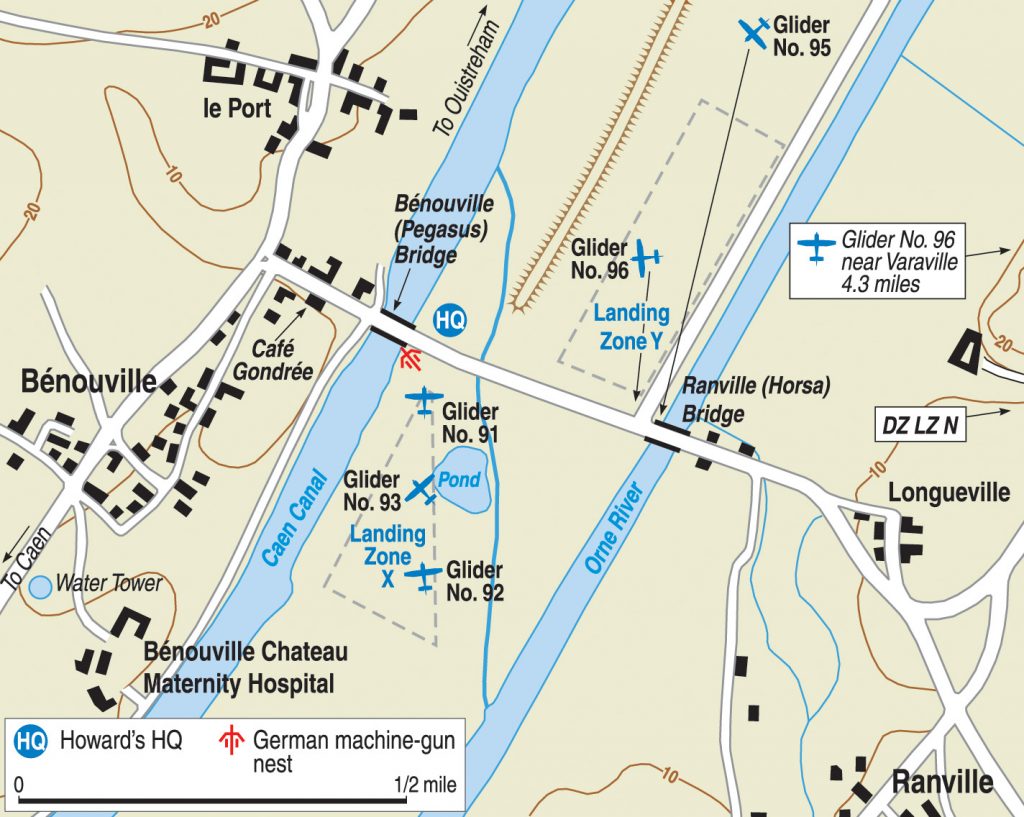

When the aircraft reached the French coast, the glider pilots released their tow cables from the Halifax bombers and began an irreversible descent into Nazi-occupied Normandy. At the controls of glider Chalk 92, Staff Sergeant Oliver Boland directed the glider toward his target, a strategically vital bridge spanning the Caen Canal. In the opening minutes of the D-Day invasion, Boland would be among the first British troops to land on the European continent. The cocksure young glider pilot suddenly found himself overwhelmed by the magnitude of the assignment. “I found it difficult to believe because I felt so insignificant [to be] the spearhead of the most colossal army ever assembled,” he said.

Boland and his comrades were an integral part of the massive Allied invasion known as Operation Overlord, which aimed at nothing short of the liberation of Nazi-occupied Western Europe. Plans for the operation began almost immediately after the stunning German victories during the spring 1940 but proceeded in earnest after America joined the Allied war effort by the end of 1941. Until America’s industrial strength could be brought to bear, vastly outnumbered Commonwealth troops waged a bold fight against Axis forces in wide-ranging campaigns around the globe.

After five years of dogged fighting, Great Britain was more than ready to strike back. Final plans for Operation Overlord, which was entrusted to American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, involved a massive amphibious operation that would initially land six infantry divisions on the Normandy coast. In all, the assault troops would assault five beaches. On the right, the Americans would assault Utah and Omaha beaches. In the center, British and Canadian troops would land on Gold and Juno beaches. On the left, near the mouth of the Orne River, the troops of the British 3rd Division would secure Sword beach before moving inland to seize the strategic road and rail hub of Caen.

In order to blunt German counterattacks and help take pressure off the troops of the amphibious landings, Allied planners opted to deploy a robust airborne component behind the enemy’s front lines. Eventually it was decided to use three divisions: the American 82nd and 101st Airborne, and the British 6th Airborne. All three divisions contained a mix of conventional paratroopers paired with glider-borne infantry. While the Americans played havoc on German formations on the Allied right, the British troops of the 6th Airborne were assigned to protect the Allied left.

The use of airborne troops on a such a massive scale was nonetheless considered an inherently risky gamble. For his part, British Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory was less than sanguine regarding the prospects of the massive airborne operation. Regarded as something of an abrasive pessimist, Leigh-Mallory, who ranked as the top air commander for the Overlord operation, cautioned Eisenhower at the end of May that the paratroop and glider insertions into Normandy were a disaster in the making. By his reckoning, half the paratroopers and a third of the gliders were sure to be lost.

For the British troops of the 6th Airborne Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Richard “Windy” Gale, the constraints of geography would dictate the battle plan. Once in its intended drop zone, the division would have its back pinned against two parallel barriers, the Caen Canal and the Orne River. Running east from the village of Benouville was a road which crossed both watercourses. Directly adjacent to Benouville was a swing bridge, complete with a two-story counterweight, that crossed the 150-foot-wide Caen Canal. Just a half mile east of the canal, a pivoting bridge crossed the tidal Orne River. The brainchild of the legendary French engineer Gustave Eiffel, the structure was an ingeniously designed affair which could pivot on a single pier in the middle of the river.

If the Germans could maintain control of the crossings, they could effectively cut off the 6th Airborne from British forces landing at Sword Beach, and then destroy the isolated paratroopers in detail. To Allied planners, it was apparent that seizing the two bridges was crucial to securing the eastern flank of the Allied landings, and consequently to the success of the entire D-Day operation. The vital need to control the crossings of the twin waterways was the genesis of Operation Deadstick, among the most daring airborne operations of World War II.

Because paratroopers dropped at night were almost certain to be scattered wide of their intended drop zone and face inevitable delays in organizing for an attack, taking the bridges before the Germans could destroy them was considered unlikely. The solution, to Gale’s thinking, was to assault and capture the bridges with specially trained glider-borne infantry.

The glider was an innovation of World War II, which already had proved its worth to both to both Allied and Axis forces. Towed by bombers, the lightweight, powerless glider would be released over its target and was capable of quietly inserting assault troops into a confined landing zone. With a picked force and a dose of good luck, Gale hoped to land elite glider troops close to the bridges and then take control of the crossings before the Germans had time to react.

Once he had settled on a general course of action, Gale approached Brig. Gen. Hugh Kindersley, the commander of his Air Landing Brigade, and asked him to suggest a company capable of such an operation. Without hesitation, Kindersley recommended what he considered the best outfit under his command, D Company of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry.

D Company’s reputation as a crack unit was due in no small part to its hard-driving commander, Major John Howard. Howard had learned the virtues of hard work and determination during his formative years in London’s West End. He served a stint in the army in the 1930s, and then found work as a policeman on the gritty streets of Oxford. When war broke out in 1939, Howard was back in uniform, quickly winning promotion and then an officer’s commission.

By 1944 Howard was a company commander in the “Ox and Bucks,” which had been attached to the glider-borne Air Landing Brigade of the 6th Airborne Division. A natural-born commander who led by personal example, he was immensely respected by his men and highly valued by his superiors. During training, Howard drove his men hard, and himself harder.

To ensure that Howard and his men were cut out for the operation, Gale scheduled a special three-day exercise and attended the event with brigadiers Kindersley and Nigel Poett, commander of the 5th Parachute Brigade. Howard and his men staged a mock landing and assault of three bridges guarded by British paratroopers who filled in as Germans. After witnessing the maneuvers, all three of the general officers in attendance were convinced that D Company was the right outfit for the job.

Soon after the exercises concluded, Howard met privately with his immediate superior, Colonel Michael Roberts, who informed him of D Company’s historic and top-secret assignment. When the Allied invasion of France materialized, Howard and his men would have the very important task of seizing two bridges that were strategically vital, Roberts said. More details on the operation were forthcoming, but Roberts made clear the magnitude of the assignment. “You will be the spearhead of the invasion, certainly the first British fighting force to land on the Continent,” he said.

D Company’s vital mission ensured that the men received the rigorous training of crack troops. Howard worked hard to create realistic training exercises, staging mock assaults on bridges that were conducted at night in order to ensure that the men were accustomed to operating in the dark. Howard was allowed to bolster his company by selecting two additional platoons, and he chose two outfits from B Company of the Ox and Bucks, giving him a total if six platoons. Each platoon was also assigned an organic contingent of Royal Engineers, who were assigned the vital task of disarming any German demolitions on the bridges.

The troops would be using Horsa gliders, a powerless 67-foot-long plywood behemoth that could deliver at least 15 men into combat. Howard repeatedly had his fully loaded and armed men practice exiting the craft. In Normandy, capturing the bridges quickly would be of the utmost importance, and a momentary delay could mean the difference between life and death.

For good reason, the young glider pilots assigned to Operation Deadstick received perhaps the most rigorous training of all. The pilots would be flying at night by means of dead reckoning, with little more than a map and a stopwatch to navigate to the landing zones. The pilots initially trained during the daytime, but ultimately resorted to flying at night or with blindfolds. Theirs was an immensely stressful job on which the entire operation, as well as the lives of their occupants, would hang in the balance.

Howard’s mission was likewise given top priority for reconnaissance flights, which provided aerial photographs of the target area. But despite the immense worth of the reconnaissance flights, aerial photographs were limited in their ability to capture the vagaries of terrain or the shifting German defenses. Ultimately, the German garrison of 50 men constructed a warren of trenches and bunkers, bolstered by a half dozen machine-gun positions and an antitank gun.

Fortunately for Allied planners, a pair of unassuming French civilians provided a wealth of priceless intelligence. Situated in Benouville directly west of the bridge over the Caen Canal, Georges and Theresa Gondree operated the Cafe Gondree, a modest watering hole frequented by German troops. Although the couple kept up appearances as inconspicuous middle-aged restaurant owners, they were key members of the French Resistance in the village of Benouville.

Madame Gondree, who understood German, was uniquely equipped to covertly gather intelligence on occupying troops. Unsuspecting German officers who frequented the cafe consequently passed along a wealth of information which made it directly into English hands. Thanks to the best aerial photographs of the target, as well as highly reliable intelligence from the couple, Howard and his men were well familiarized with the bridges, their defenses, the surrounding terrain, and specific enemy dispositions.

On June 5, 1944, Eisenhower issued orders for Operation Overlord to go forward. Howard’s men were given the day off in order to rest, but few could sleep. That evening the men, heavily armed and loaded with ammunition and supplies, boarded six Horsa gliders at the Tarrant Rushton airfield. At 11:00 pm the Halifax tow planes lifted off the runway. The troops braced themselves as best they could for the ultimate test; some were lost deep in thought, most burst into song in order to relieve the tension. “The atmosphere in the glider was somewhat like a London tube train in the rush hour,” said Clark. “We were in good heart.”

It was a short flight, and at seven minutes past midnight, the festive atmosphere ended abruptly. Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork, at the controls of the lead glider, released from the tow line as soon as he was over the French coastline. As soon as the men realized that they were no longer tethered to the Halifax tow planes, the singing stopped. The ominous silence aboard the Horsas seemed to emphasize the stark reality of the mission; if the pilots could land successfully, the British troops would be on the ground in a matter of minutes and facing a baptism of fire.

Wallwork bore an unenviable weight of responsibility for the success of the entire operation. He and his co-pilot, John Ainsworth, were virtually flying blind and forced to rely on their instruments and stopwatch. Precisely three minutes and 42 seconds after casting off from the tow plane, Ainsworth gave the signal to Wallwork to turn the glider to starboard, steering for the Caen Canal.

Near-panic set in as visibility remained nearly nonexistent. Wallwork cast fitful glances out the window as he desperately searched for sign of the Bois de Bavent, an immense forest the pilot had hoped to use as a landmark to fix his position. “For God’s sake, it is the biggest place in Normandy,” said Ainsworth. “Pay attention!”

Giving up hope of sighting the forest, Wallwork made one more starboard turn, bringing his Horsa to a northward course parallel with the Caen Canal. As he did so, he slowed the glider to 110 miles per hour and executed a rapid descent, falling from 7,000 feet to a mere 500 feet as he rapidly approached the target area. Forced to rely on his instruments, and with no possibility of a second chance, Wallwork faced the real possibility of wrecking his glider and killing every man aboard.

And then something miraculous happened. Wallwork abruptly caught sight of the landing zone and discovered that he was precisely on course. Ainsworth’s navigation had put them right on target. Shouting for Howard and the men to get ready, Wallwork began the final descent to the landing zone. As the troops shouted, linked arms, and raised their feet from the floor of the Horsa, Howard could see that the young pilot was straining under the greatest responsibility of his life. “I could see old Jim holding that great bloody machine, and driving it in at the last minute,” recalled Howard. “The look on his face was one that one could never forget. I could see those great damn footballs of sweat all over his face.”

Coming in over the treetops at nearly 100 miles per hour, the Horsa slammed into the ground at the northern edge of the landing zone with a deafening crash that knocked every man on board momentarily unconscious. Wallwork and Ainsworth, ripped from their safety belts, were thrown through the front windows of the glider. The impact of the landing had caused Howard’s helmet to fall down over his eyes, and as he slowly regained his senses, he thought perhaps that he was either blind or dead.

As glider landings go, it had been a near perfect one. Wallwork had succeeded in bringing the nose of his glider to rest against a barbed-wire entanglement on the northern edge of the landing zone, and the Horsa was a mere 150 feet away from the canal bridge. Amazingly, German defenses at the bridge were quiet. In mere seconds, the troops were on their feet and gathering equipment. Lieutenant Herbert Denham “Den” Brotheridge, flinging open the exit door, motioned to a Bren gunner to get on the move. “Gun out!” shouted the lieutenant.

Howard’s men piled out of the Horsa and made a mad dash for the bridge. In the opening moments of the fight, little mercy would be shown as the glider troops struggled to overwhelm the Germans before they could mount an adequate defense. When Private Billy Gray ran up the road bank, he noticed a startled German and quickly cut him down with a burst from his Bren Gun. Private Wally Parr, shouting at the top of his lungs, ran for a bunker on the northern side of the road. When he reached it, he opened the door and threw in a grenade. Still hearing a muffled voice from inside, he flung the door open and unleashed a burst of fire into the structure.

The British had caught the Germans by complete surprise. Private Helmut Romer, who was stationed that night as a bridge sentry, noticed some sort of aircraft crash east of the bridge, but assumed it was a portion of an Allied bomber that had been downed by anti-aircraft fire. When screaming British troops came running in his direction, he realized his mistake and quickly turned heel. Peering out the window of his cafe, Georges Gondree could see a panicked German soldier running pell-mell for the western end of the bridge. “Parachutists!” screamed the terrified soldier. Another German, hoping to rouse the garrison, succeeded in firing a single alarm flare, which arced high in the sky above the canal.

By then, though, it was too late. Brotheridge was at the head of his platoon, racing across the bridge ward Benouville. Gunfire erupted along both sides of the bridge, but Brotheridge’s men reached the west bank in seconds, where they fanned out to secure the surrounding buildings. As some of the men regrouped in front of the shuttered Cafe Gondree, they suddenly realized that Brotheridge was missing. Wally Parr then noticed someone sprawled in the road and knelt down beside him. It was Den Brotheridge.

He had been shot through the neck and lay motionless on his back. “His eyes were open, and his lips were moving,” said Parr. “I put my hand behind his head to lift him up; his eyes rolled back, he just choked and lay back.” Brotheridge would be the first Allied soldier killed by enemy fire on D Day, and Parr was struck by seemingly pointless tragedy. Brotheridge had been in action only about 30 seconds and he was dead. “What a waste,” Parr said.

While the tremendous crash of gunfire grew louder around the bridge, the rest of the Horsa gliders continued to arrive at the landing zone east of the canal. The second glider to arrive at the battlefield, carrying Lieutenant David Wood’s platoon, approached the landing zone just one minute behind Wallwork.

Its pilot, Oliver Boland, was worried he would crash into the tail of the lead glider, and desperately deployed a parachute brake. Wood was thrown out of the craft on impact, but quickly formed up his men and ran for the road embankment, where he found Howard. The major was taking cover from German fire just feet away. He immediately ordered Wood to assault the trenches on the north side of the road. After months of training, the men were anxious to get into the fight. Wood and his men charged up the embankment and across the road “like a pack of unleashed hounds,” said Howard.

Howard’s men gained control of the bridge before the Germans had an opportunity to destroy it. As they scrambled around the girders of the bridge, the engineers discovered that the structure had been wired for demolition, but the explosive charges had never been installed.

While the fighting intensified, the third glider reached the landing zone. Sergeant Geoffrey Barkway, at the controls of the glider, found it difficult to find open ground on the landing zone already littered with two other gliders. He likewise employed his parachute brake, bounced his craft on landing, and then came down hard with a tremendous crash that broke the glider in half.

The impact sent Lieutenant Sandy Smith, the platoon commander, crashing through the front window of the Horsa. The lieutenant landed dazed and confused in the mud. Another unfortunate trooper, weighed down with an immense load of gear and ammunition, ended up bogged down in the marshy pond and drowned. Smith staggered to his feet, just as one of his men said something to motivate the platoon. “Well, what are we waiting for?” the soldier said.

The operation to seize the bridges would benefit from such aggressive initiative. Smith, limping on an injured knee, led his platoon across his bridge to the western bank of the canal but immediately ran into trouble. A retreating German tossed a grenade at Smith, and then leaped up over a wall to escape. Smith caught him before he could get over the wall and fired a lengthy burst from his Sten gun into the German at point blank range. When the firing was over, one of Smith’s men ran to his side and asked if he was alright. During the chaos of the fight, Smith had failed to notice that his forearm had been badly mangled by the grenade blast. “I saw that the whole of my wrist was bare,” said Smith.

Despite the success at the canal, it still remained for the men of the Ox and Bucks to seize the bridge over the Orne River. The glider landings there, though, did not go according to plan. The Horsa carrying Captain Brian Priday’s platoon veered badly off course and landed beside a bridge at Varaville, a good eight miles from their target. Another glider, carrying Lieutenant Todd Sweeney’s platoon, met with unexpected turbulence as it approached the landing zone and ended up touching down 1,300 yards from the bridge. Although Sweeney quickly had his men on the move, they would be behind schedule for the initial attack.

Lieutenant Dennis Fox and his platoon would face an equally harrowing ordeal. As he brought their Horsa in for a landing, Staff Sergeant Roy Howard had to fight to keep the nose of his glider up and finally ordered two men toward the rear of the craft in order to distribute the weight. Thanks to his quick thinking, the landing went perfectly; the Horsa’s wheel’s broke off on impact and then the craft slowly skidded to a stop. Howard’s piloting had put Fox’s platoon down within sight of the river bridge. “To hell with it, let’s get cracking,” Fox said. He led his men in a sprint for the bridge.

As they neared the river, a German machine-gun crew on the far bank spotted them and opened fire. Sergeant Charles “Wagger” Thornton quickly set up a 2-inch mortar and lobbed two shells over the river. As the British troops ran across the bridge, shouting as they charged, the rattled Germans scattered. In minutes, the bridge over the Orne River had been seized nearly without a fight. In less than 30 minutes, Howard’s elite troops had succeeded in seizing both of their objectives. Radio operators began transmitting the code, which was “ham and jam,” for the successful capture of the bridges.

Despite the success, holding the bridges from an inevitable German counterattack would result in a far bloodier ordeal. Since British paratroopers would take over responsibility for the river bridge, Howard left just a single platoon there and consolidated the rest of his command at the canal, which was almost certain to face a fierce German counterattack. For the coming fight, Howard kept one platoon east of the canal as a tactical reserve, with three platoons west of the canal to stop any German push.

It did not take long for the Germans to begin probing Howard’s defenses. Fresh from the assault on the river bridge, Lieutenant Fox led his platoon forward to the crossroads west of the canal bridge. Out in front was Fox’s most experienced non-commissioned officer, Sergeant Thornton. When the platoon reached the road junction, Fox set up his command post at the village church while his men took up defensive positions.

Scattered small-arms fire persisted, but at 2:00 am Fox was alarmed by the ominous rattle of tracked vehicles. He could see very little, but it was obvious that the anticipated counterthrust of enemy armor was headed straight for his lightly armed platoon. Behind Fox, Lieutenant Sandy Smith felt the same helpless sensation. “My God, what the hell am I going to do with these tanks coming down the road,” he said. The troops only had a single Piat 83mm anti-tank weapon and assumed that they were about to be overrun.

Just 30 yards away from the crossroads, Sergeant Thornton had other ideas. He had little faith in his inaccurate Piat but moved dangerously close to the road junction for a good shot at the enemy. In the darkness, no one could quite make out what was coming at them. Thornton could eventually make out three vehicles; some witnesses thought that they were Mark IV Panzers, others thought they were captured French tanks. Regardless of exactly what the vehicles were, the British were badly outmatched. Thornton confessed to “shaking like a leaf” as he waited for the enemy to come within range.

Clearly unsure if they should head for the canal bridge, the Germans halted the vehicles to assess the situation. It was the opportunity Thornton was waiting for. Still trembling, he took aim at the lead vehicle and fired the Piat. It was a perfect shot and hit the lead vehicle square in the side, penetrated the armor, and exploded. Several Germans scrambled from the hulk, and Private Woods opened fire on them as they dashed for safety. At that point “all hell broke loose,” said Thornton.

The Piat round began setting off ammunition inside the German vehicle, which exploded into a veritable inferno. The tremendous crash of the explosion, as well as the glow of the fire, could be seen for miles, helping British paratroopers farther east to find their bearings in the dark. Closer to the bridge, Howard’s glider troops, including an astonished Thornton, crouched for cover as the ordnance continued to explode. Between explosions, the terrified soldiers could hear the screams of a wounded German who struggled to escape the wreckage.

In the midst of the horrific scene, humanity overcame terror. Private Tommy Clare broke from cover and ran straight for the burning wreck, where he found a wounded German, writhing in the middle of the road and missing both of his feet. Clare threw the stricken man over his shoulders and ran back toward a British aid station. Despite the carnage, Thornton’s remarkable shot with the Piat had blocked the road junction and bought precious time for the defenders of the canal bridge. German officers, convinced that the British were in possession of anti-tank guns, pulled back to regroup.

The single platoon at the river bridge, commanded by Lieutenant “Todd” Sweeney, anxiously awaited relief from the British paratroopers of the 6th Airborne. Sweeney’s men had ambushed a German infantry patrol that had approached along the riverbank, but they dreaded the prospect of a counterattack by German armor. In the darkness, Sweeney heard the approach of a tracked vehicle. “Well, here we go,” he thought to himself. “This is the first tank attack.”

Fortunately, he was mistaken. Just two vehicles were making for the bridge: a single halftrack followed by a motorcycle. Sweeney’s men jumped up from the side ditches and opened fire. The motorcyclist was hit and careened out of control, while the halftrack, swerving violently, sped across the bridge. When it neared the far side, a quick-acting British soldier leapt to his feet and tossed a hand grenade into the open back of the halftrack. The explosion sent the vehicle into the ditch.

When the British troops rushed for the wreck, they discovered an unexpected prize. Inside the smashed halftrack was Major Hans Schmidt, commander of the German bridge defenses, who was suffering from a badly injured leg. The wound to his ego was worse. At the British aid station, an apoplectic Schmidt harangued Doctor John Vaughan on the folly of the Allied invasion. “Your troops are going to be thrown back,” Schmidt thundered. “My Fuhrer will see to that: you’re going to be thrown back into the sea!” The hysterical Nazi begged to be put out of his misery, pleading “Shoot me, doctor!” An amused Vaughan brushed him off and gave him a shot of morphine.

Far from being thrown back into the sea, the British were beginning to consolidate their gains in Normandy. As expected, the airborne drop had been messy. The 7th Parachute Battalion, consisting of 640 men, could only concentrate 210 men on the ground in Normandy. Howard was nonetheless more than a little relieved when they arrived, and immediately ordered them to the western end of the canal bridge.

When they reached the road junction, the paratroopers fanned out, taking up defensive positions in Benouville and Le Port. Despite an incredibly close call, British possession of the bridges was secure for the moment. Reinforced by the paratroopers, Howard pulled his advanced troops out of the front lines and consolidated east of the canal.

By dawn, the fight for the bridges was largely confined to small-arms fire, but greater chaos erupted to the north. In the hope of softening up German coastal defenses, Allied warships in the English Channel opened up a deafening bombardment as the amphibious landings got underway. While they anxiously listened to the greatest bombardment in history, the troops at the bridges felt the ground tremble under their feet. For his part, Howard was thankful to have joined the invasion by glider rather than with what he said were “those poor buggers coming by sea.”

As soon as the sun slowly began to crest the horizon, the greatest danger to the British troops was the persistent threat of German snipers, who used the daylight hours to grim advantage. Howard’s men, who continued to take casualties, grew increasingly frustrated in not being able to strike back at the well-concealed German snipers, who had an excellent view of the exposed ground around the canal bridge.

No one was safe. Lieutenant Smith, while receiving treatment in a roadside ditch, watched in horror as his medical orderly stood up and was struck in the chest by a single rifle shot. The man sprawled across the road screaming, while a terrified Smith felt certain that he was in the sniper’s sights. The orderly fortunately survived, but others would not be so fortunate.

When Private Harry Clark escorted two German prisoners to the holding pen at Ranville, he came across a wounded paratrooper by the roadside. The man, who had been hit by a sniper, had been shot through the spine and was clearly dying. The stricken man begged Clark to put him out of his misery, but a rattled Clark pressed on with his prisoners. For the rest of the morning, any British soldier that lingered in the open was courting death, and German snipers sent a steady stream of wounded men to the aid stations.

While the sniper fire continued, the troops at the bridges were rewarded with a much-needed dose of encouragement. At 9:00 am a trio of senior officers coolly walked onto the field from the direction of Ranville. It was Gale, flanked by Generals Poett and Kindersley. As he passed Howard’s battle-weary soldiers, the unflappable Gale, as if on a morning stroll, greeted them as if it were any normal day. “Good morning, chaps,” he said. With the arrival of the highest-ranking officers of the 6th Airborne, it seemed increasingly likely that the British would successfully hold the bridges and secure the left flank of the Allied invasion.

But before substantial reinforcements arrived, the airborne troops would be subjected to incessant German probes and harassing fire. When an enemy gunboat, armed with a 20 mm gun, came upstream toward the canal bridge, the British had just a single Piat with which to confront it. Remarkably, Corporal Claude Godbold, firing from concealment, scored a direct hit on the gunboat, which drifted out of control into the bank, where its startled crew was taken prisoner.

Not long afterwards, Howard’s outgunned command improvised more robust firepower. Private Wally Parr, manning the captured German antitank gun, opened up on yet another enemy gunboat which approached the canal bridge. Parr scored two hits before the gunboat headed back toward Caen. Not quite satisfied, Parr then commenced firing at any high point that might offer cover to enemy snipers. After drilling a pair of holes through the village water tower, he turned his attention to the Chateau de Benouville. After landing three hits on the structure, a furious Howard ordered him to cease fire. Unbeknownst to Parr, the chateau was being used as a maternity hospital.

Fortunately for the airborne troops holding on at the bridges, help was on the way. The initial British landings at Sword Beach had gone off surprisingly well, and the crack troops of the 1st Special Service Brigade, under the command of Brigadier Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, began pressing south from the coast, flanking the Caen Canal and moving fast to the support of the 6th Airborne. Fortunately, German resistance was relatively light, and Lord Lovat’s commandos made good progress.

But in a characteristically British display of audacity, Lovat had a jaunty surprise for the airborne troops. Out in front of the relief column marched a pair of men. One was Lovat, who was leading by personal example, and the other was piper Bill Millin, who was loudly playing a lively tune on the bagpipes. As the first notes of the bagpipes drifted to the bridge, Howard’s men couldn’t believe their ears. When Lieutenant Sweeney mentioned that he thought he heard bagpipes, Sergeant Thornton made a terse remark. “Bagpipes?” he said. “What are you talking about? You must be bloody nuts.”

Within moments Lovat and Millin came into view, and the bleary-eyed airborne troops were incredulous at the surreal spectacle that greeted them. But the sight of the commandos stretched out behind Lovat meant that success was at hand: a link up with the troops from Sword Beach heralded a secure foothold in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Despite the heady nature of the commandos’ arrival, they had walked into a hornet’s nest. Steady small-arms and mortar fire continued to blanket the area, and German snipers immediately began targeting the newcomers. As Lovat’s exhausted troops crossed over the canal at a slow walk, they made easy targets, and the surface of the bridge was quickly dotted with slain commandos.

Once on the east bank of the canal, Lovat was greeted by Howard, who could only think to apologize for the mortar fire coming from the direction of the maternity hospital. With an outstretched hand, Lovat paid the ultimate compliment to the heroic efforts of Howard’s men. “John, today history is being made,” Lovat said.

Lovat’s offhanded comment wasn’t an exaggeration. Although the British troops controlling the bridges would continue to accrue casualties, both crossings would remain firmly in Allied hands. Thanks to an ungainly German command structure, nearby Panzer columns would remain motionless, ensuring that the 6th Airborne’s grip on the bridges would be steadily reinforced. Using the precious window of time, the Allies secured their toehold in Normandy with a rapid influx of armor and artillery.

Late on the evening of D-Day, elements of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment relieved Howard and his men, who then rejoined the rest of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. They had trained for the operation for months and had succeeded beyond any expectation. But in the immediate aftermath of the fight for the canal bridge, the crossing quickly garnered a new name that paid homage to their sacrifice. The Benouville Canal Bridge was quickly renamed Pegasus Bridge in honor of the mythical winged stallion that emblazoned the shoulder patch of the 6th Airborne.

The historic achievements of John Howard’s hand-picked glider troops at Pegasus Bridge could not be overstated. By seizing the crossings of the Orne River and Caen Canal intact, the glider troops of the Ox and Bucks had secured the vital lines of communication to the British 6th Airborne Division, which anchored the left flank of the Allied landings in Normandy. Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory, who had always maintained a pessimistic view of the Allied airborne operation, was nonetheless effusive in his praise for the warriors who had taken Pegasus Bridge. The entire operation had succeeded due to the remarkable coolness of the young glider pilots, who had pulled off “the greatest feat of flying” of World War II, said Leigh-Mallory.