By John W. Whitman

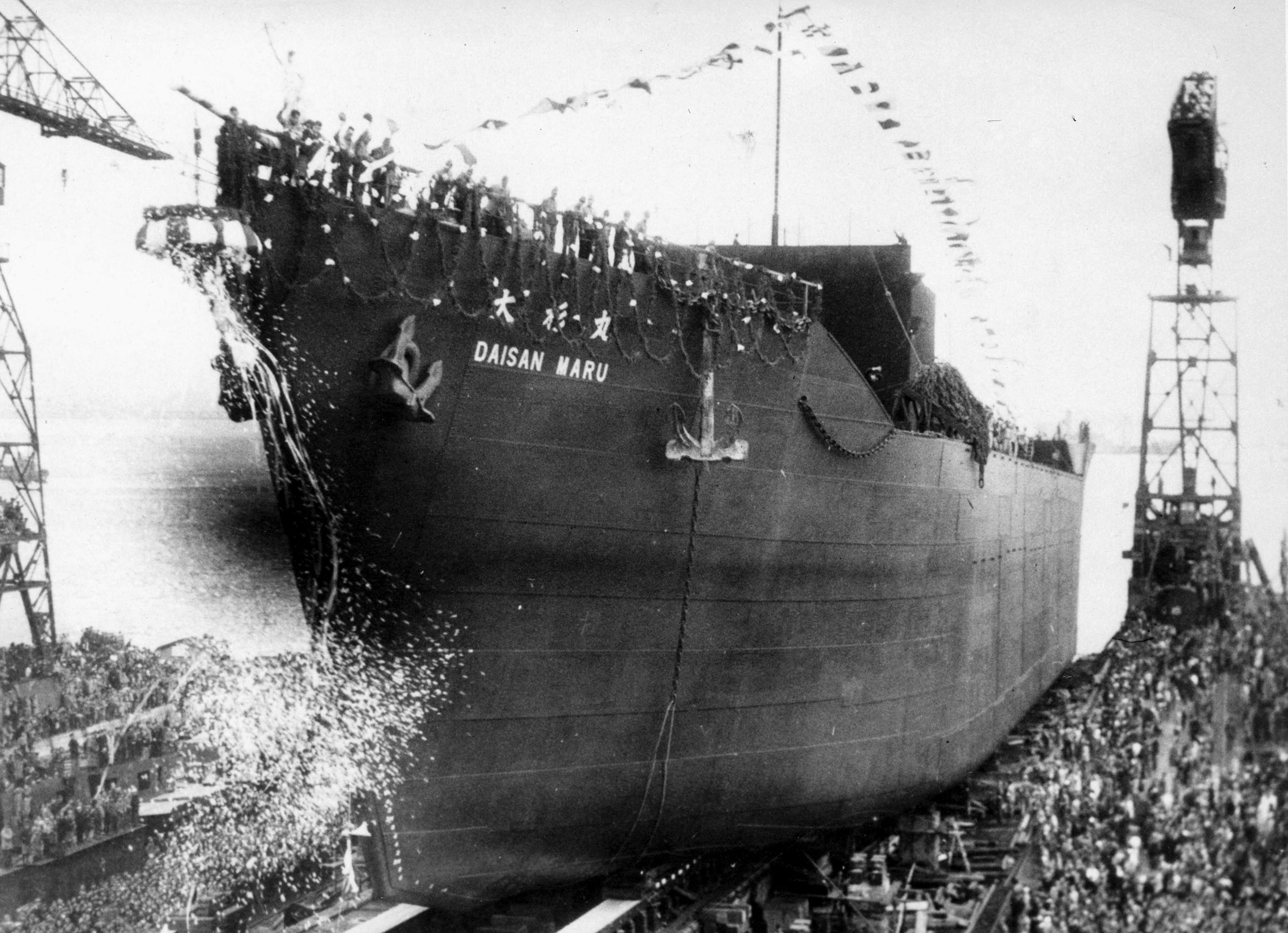

Japanese military successes in 1941 and 1942 shocked the West. Behind those successes lay a logistics effort not often appreciated, that of shipping. The Japanese wrote off any immediate requirement to support normal trade when war began. So the nation dispatched ships normally engaged in that effort to support invasion forces. This healthy pool of ships moved large numbers of men, equipment, and supplies over a short period. They did this within normal man per square foot ratios. Shipboard crowding was no more drastic than usual.

Herculean Movements by Sea

The first four months of war saw the best Army lift capacity the Japanese would ever know. Once the Army secured its objectives, Tokyo withdrew many ships to carry the raw materials from those conquered lands back to Japan. After the initial deployments, lift capacity declined, with fewer and fewer ships moving more and more men.

The Japanese moved 14 Army divisions/divisions minus (flags) by sea during the first 13 months of the war. More impressive is the number of lifts, that is, the number of times a division moved by sea after an interruption such as disembarking, campaigning, and then embarking for the next objective. For instance, the well-traveled 2nd Division sailed in three separate lifts. The division’s Japan-Formosa-Camranh Bay-Java travel was one lift, using the same ships throughout. Java-Rabaul required different ships and thus was a second maru lift, while the dash to Guadalcanal was a third. The 4th Division went from Shanghai to Luzon, campaigned there, and then returned to Japan, therefore two division lifts. Japan executed at least 28 full lifts of divisions or divisions (minus) with elements, such as a regiment or more temporarily detached, by the end of 1942.

Independent brigades, independent regiments, and similar equivalents such as independent garrison units also deployed. Tank regiments (actually battalions in Western eyes) and divisional infantry regiments moving independently of the division needed transport and cargo space. The Japanese managed about 71 regimental equivalent lifts. The different sizes of these regimental units meant that the equivalent of 10 more divisions needed sealift.

When one adds nondivisional field artillery, engineers, signal, and antiaircraft units, another 50 major units needed 80 lifts, the equivalent of eight divisions. The 20th Engineer Regiment, for instance, fought at Hong Kong, then sailed to Malaya. It campaigned there, then sailed for Rangoon; thus, one regiment (actually a big battalion), two lifts. The 23rd Independent Engineer Regiment sailed from Korea to Malaya, then Malaya to Manchuria; therefore, one regiment, two lifts.

Army air divisions and Navy air flotillas island-hopped from their December 8, 1941, bases toward the fighting. Fifth Air Division supported the fighting in the Philippines from Formosa, then flew to airfields on Luzon, and later flew even farther south. Ships moved ground support units, munitions, and fuel. Aircraft flew into Rabaul when the Sixth Air Division activated in late November 1942, but everything else came by sea. There were also air divisional antiaircraft, intelligence, signal, maintenance, engineering, administration, and transportation elements, all of which moved by sea.

Naval air flotillas were equally active. In three cases, these aircraft initially drew support from prewar bases: the 21st Air Flotilla on Formosa, the new 25th that activated on Truk, and the new 26th that activated in Japan. Once they moved, supplies had to follow them by sea. Emplacement logistics of air divisions and air flotillas required a rough total of five divisional equivalent lifts in 1941-1942.

Deploying Specialized Forces

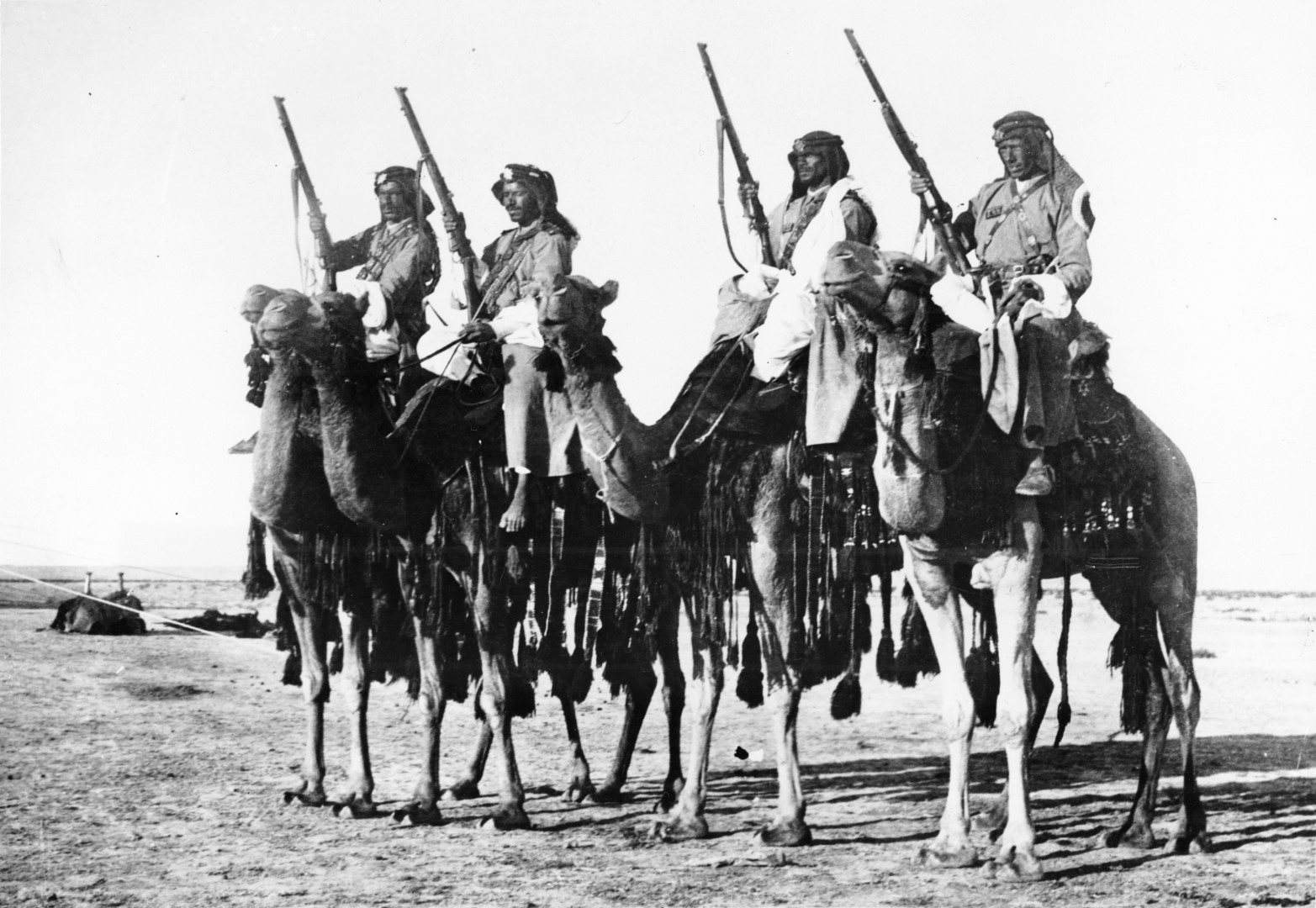

There were also minor forces such as special naval landing forces (SNLF), each roughly the size of a large battalion or a small regiment of infantry, sometimes armed with seacoast artillery, antitank, and antiaircraft guns. An SNLF unit could travel on one or more marus or on warships. Kure 1st SNLF moved from Peleliu to Legaspi in the Philippines aboard the 7,024-ton cargo ship Matsumoto Maru. The Kure 6th traveled aboard two heavy cruisers while moving from Japan to Rabaul.

The biggest SNLF needed sealift at approximately 25 percent (manpower) of an Army regimental slice (regiment plus normal divisional field artillery, engineers, transport medical, etc.; three regimental slices equated to a division). A heavy SNLF, with field artillery and antiaircraft, equaled a regimental slice of sealift for its equipment. However, an Army regimental slice of vehicles and tanks overwhelmed an SNLF’s modest transportation. So, an SNLF slice was, overall, roughly 20 percent of an Army regimental slice, or about one 15th of a division when sealift was required. By the end of 1942, 18 SNLFs and their equipment had moved or landed 54 times. An estimate of troop lift required to move the SNLFs is about three divisions worth.

Naval construction units were similar in manpower to SNLFs and operated as semi-military engineers. They did have some mechanized equipment, but they were mostly pick and shovel guys. Cadre consisted of naval officers and Japanese civilian engineers. These heavy battalions built airfields, fortifications, barracks, and other structures. They sailed the Pacific aboard standard marus. Their transport might equate to one or two division lifts through 1942.

Naval Base Forces

Naval base forces are difficult to quantify. Base forces garrisoned captured islands, ports, and airfields and defended them with artillery, seacoast guns, and antiaircraft guns. Light naval forces like minesweepers and subchasers protected local waters. The Navy at one time or another operated at least 53 naval base forces and special base forces. Base forces and special base forces varied widely in men and weapons and ranged from battalion strength to that of a division.

On December 8, 1941, these base forces were especially strong in light naval vessels. Sixth Base Force in the Marshalls had one minesweeper division, one gunboat division, four subchaser divisions, assorted marus, and significant coast and antiaircraft artillery. A few light detachments from base forces invaded small islands early in the war. For instance, 5th Defense Force, a regiment size unit subordinate to 5th Base Force in the Marianas, organized an SNLF of 400 men. That group along with Army elements invaded Guam on December 10.

As the war turned against Japan, base forces became extremely heavy in coast artillery and antiaircraft guns. In very rough terms, all the base forces the Japanese ever operated during World War II equated to 11 or more Army divisions, at least in raw manpower and numbers of artillery. Base forces had communications and medical support similar to Army divisions, were weaker in ground transportation, and had much heavier artillery and construction engineering support. Transporting and sustaining all these units required shipping.

Getting the 2,500 or so men of the 7th Naval Base Force and its logistics from Japan to Lae, New Guinea, by June 1942 probably equaled a quarter of a division lift. Getting the large 8th Base Force to Rabaul, New Britain, over time required shipping for 21,570 men and their stores and equipment. Naval guard forces, formations varying in strength between battalions and regiments, brought in coast defense and antiaircraft artillery. All of the Rabaul shipping probably required a two-division lift effort.

It most likely required a division’s worth of shipping to transport the 13,000 men and equipment of 1st Base Force from Formosa and elsewhere to Buin on the island of Bougainville. The 14th Base Force of 4,500 men on New Ireland no doubt required a lift of about a third of that of the 1st Base Force. Similar lifts to establish port facilities, air bases, and defenses at Singapore, Rangoon, Manila, Davao, Cebu, Tawi Tawi, and Batavia, to name just the larger ports, required lots of ships.

The Japanese naval base forces probably required the equivalent of 12 divisional lifts in 1941-1942. The Navy transported all these forces over 13 months, not in one large lift. Regardless, it required shipping to get them there, and it would require shipping to sustain them.

Japan’s Naval Lifting Strategies

The saving grace for the Japanese was that most distances early in the war were relatively short. Japan had completed numerous long hauls to assembly areas before the war began. The invasion of the Philippines staged from Formosa and the Palaus. Malaya staged out of Hainan Island and French Indochina. Rabaul to Guadalcanal in August 1942 was a short but extremely dangerous distance. Some of the Solomons moves utilized barges or warships and were not, therefore, a drain on merchantmen. The distance from Malaya to Sumatra was so short that native craft could carry some of the men. On the other hand, hauling the 1st, 6th, 7th, and 8th Tank Regiments from Burma, Malaya, Luzon, and Java, respectively, back to Manchuria necessitated long-haul trips requiring hold and deck space for men, vehicles, munitions, and spare parts.

December 1941 saw the largest number of men (unit flags) move by sea, six Army divisions and 11 brigades and regiments, some of which moved several times. These ships then cycled back for lifts in January and February 1942. January included three division moves, and five more divisions were transported in February. In March, two moved, and in April, one. Only one division was transported by sea between May and August. That division, the 4th, actually returned to Japan.

So, other than moving 11 separate brigades, regiments, or independent garrison units forward and three back between May and August, the Army needed shipping only for routine sustenance. This was fortunate, for Japan’s economy badly needed ships to move raw materials up to the Home Islands from occupied areas.

The Navy displayed a similar pattern: large lifts over the first four months to move special naval landing forces, naval construction units, base forces, and air flotillas, then a decline in deployment shipping. A different lift curve quickly appeared, that of an upward sustenance curve of merchant and naval assets to keep the deployed forces functioning. That curve climbed upward once these advanced elements encountered Allied counteroffensives.

Japan expanded in one great effort using ships normally dedicated to trade. In the process, the lift equivalent of more than 62 divisions was transported. The combat personnel and equipment were carried in a mix of combat-loaded marus, administratively loaded marus, and warships. The military succeeded in moving its men and equipment in 1941 and most of 1942. Those successes gave planners a false sense of security concerning the nation’s ability to deploy and sustain its forces.

Losses in Ships, Decline in Efficiency

In 1943, the Japanese lost 335 Japanese warships and marus totaling 1.5 million tons from attacks by U.S. submarines alone. Another million tons were sunk owing to other causes. American submariners were learning their trade. As a result, the Japanese merchant marine lost 37 percent of its capacity to all causes. This number becomes even more ominous considering that the production of new shipping during the period is included in this figure.

In December 1941, the Japanese had sufficient shipping so that five gross registered tons of shipping moved one soldier. By late 1943, space had become so tight and so many ships had been returned to service the war economy that one gross ton moved each soldier. Dispatchers loaded ships well beyond safety limits. Overloaded ships suffered mechanically. By December 1943, the Japanese were jamming five times more troops and equipment into each transport than they had in 1941. Longshoremen stacked filled oil and gasoline drums on decks of cargo ships and among troops. Army divisions left behind more and more unit equipment when they moved.

Four infantry divisions moved in January, and two divisions sailed in March. The rest of 1943 averaged one division moving each month. Throughout the year, 12 divisions (flags) made 15 moves. Most of these were long-haul moves rather than tactical, and they required a serious commitment of ships and time. Six moves were as far as one could sail and still stay within the empire. Only two of the moves were short. Two Army air divisions moved in three short lifts; a light division equivalent of an SNLF moved in 14 battalion-size lifts; and the equivalent of 18 independent brigades, independent regiments, or divisional regiments sailed in 21 lifts.

Compared with their moves of 1941-1942, the Japanese had obviously placed a number of units where they wanted them in 1942 and did not need to move large numbers in 1943. Naval base forces, for instance, were substantially in place. Although these base forces needed resupply, and some received reinforcements, they did not need the more logistically difficult emplacement.

Warships as Lift Ships

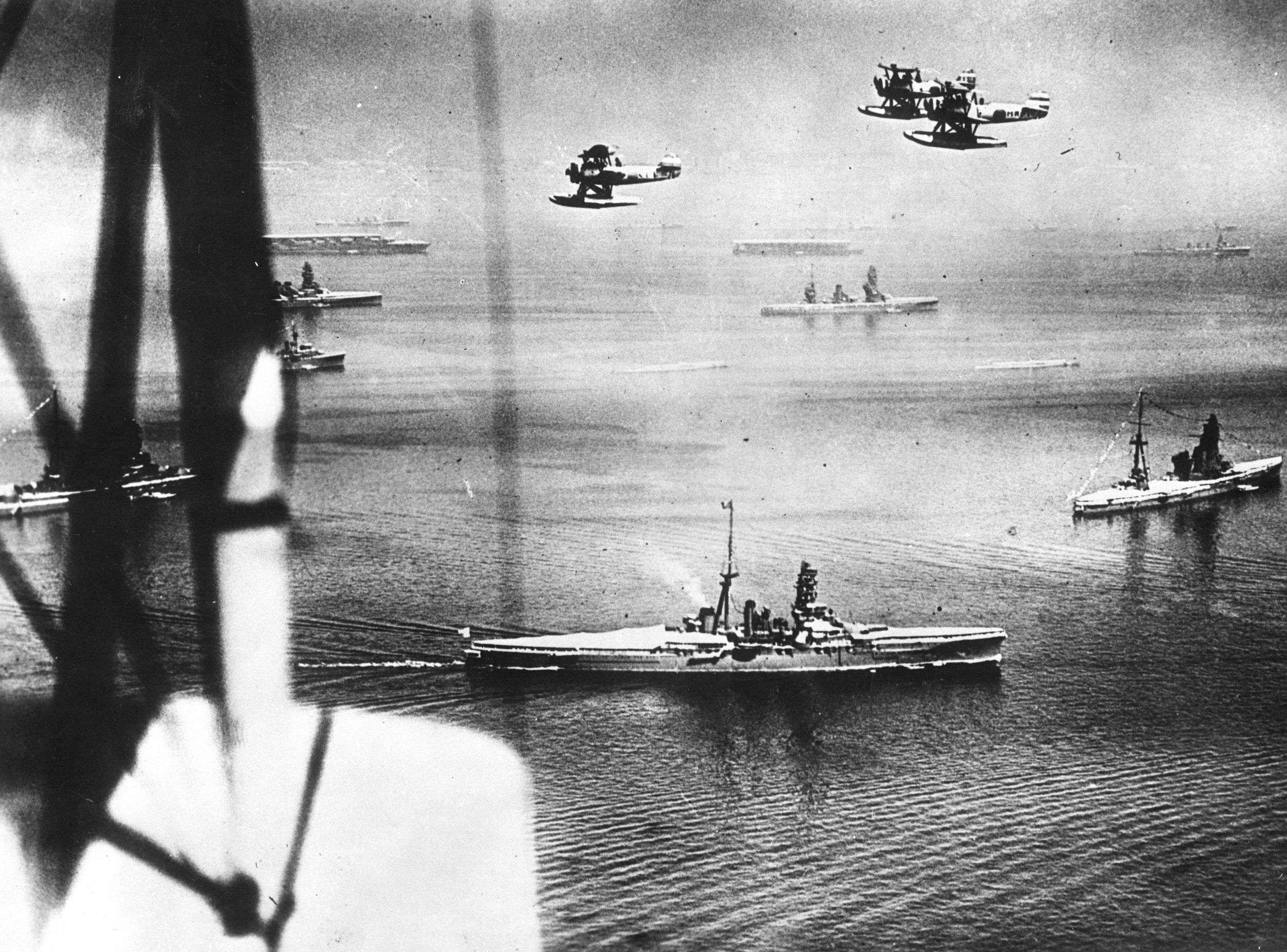

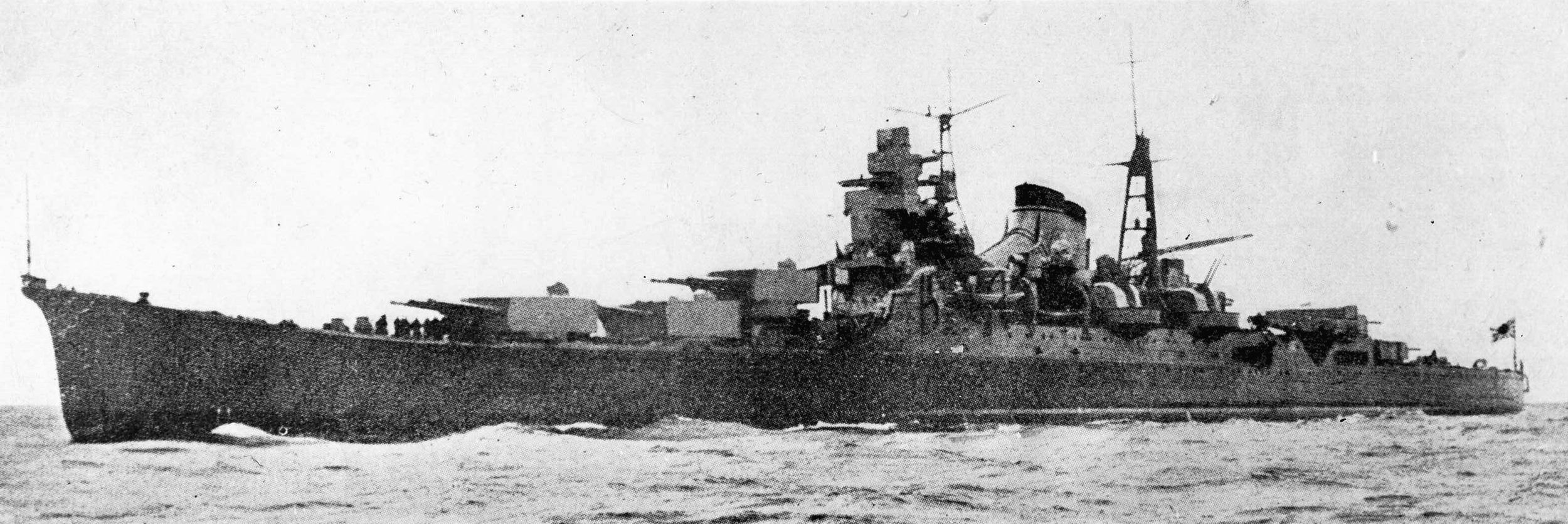

So troublesome had shipping shortages and losses become and so vulnerable were merchantmen that Japanese aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and auxiliaries started carrying naval logistics and Army soldiers and supplies. The Navy had not done this with any frequency until Guadalcanal. Using warships certainly reduced vulnerability because they were fast, agile, and carried robust antiaircraft defenses. Such use, however, put a strain on ships not built for this purpose. Nor was it economical in fuel oil. It was, however, successful.

As Japan’s aerial situation deteriorated, and as slow marus became more vulnerable to aircraft and submarines, cruisers sailed on 86 logistics missions in 1943. There were no losses while carrying troops or equipment, although some cruisers did suffer damage. Destroyers also saw their commitment to logistics lifts increase. Fleet, light, and escort carriers teamed with battleships to make logistics runs.

Supply requirements for forward forces continued an uninterrupted rise. For every sailor and for every soldier dispatched to the Gilberts or Marshalls or to Java or Burma, the military needed shipping to carry forward that individual’s munitions and food. The nearly 20,000 sailors in the Gilberts and Marshalls could not live off the land, so repeated supply trips were necessary. The stronger such a force became, the more supplies it consumed.

In 1944, the Army sent by sea more units than it had moved since the war began. Japan endeavored to move 28 divisions (some in more than one lift, therefore totaling 32 division lifts); nine air divisions or air flotillas (11 lifts); four division equivalents in expeditionary units, and about 41 independent mixed brigades, tank regiments, detached divisional regiments, and independent regiments (50 lifts). Minor nondivisional artillery and the nondivisional logistics tails for the combat elements also sailed. For instance, three naval construction units sailed for Guam and Tinian. A stunning 1.8 million troops were moved by sea in 1944, and 83,293 died, an equivalent of six to seven divisions.

As in 1943, Japan’s Navy dipped into its combat vessels to provide fast lift assets. The Navy made available aircraft carrier, battleship, and cruiser space during routine deployments of ships from one port to another. In February, the super battleship Musashi loaded an Army battalion and an SNLF, munitions, fuel, food, and vehicles. The crew lashed bombs to the deck ahead of the forward turrets, secured oil and gasoline amidships, and tied down trucks aft. Musashi and three destroyers sailed for Palau. A typhoon washed most of the ammunition deck cargo overboard, but the ships reached Palau intact on February 29.

There is only a modest correlation between Musashi’s troop load and that of the Jolo Force, a detachment from the 56th Brigade that sailed in 1941. Yet, a comparison is interesting. The Jolo invasion force of 4,000 men sailed in nine marus grossing 52,467 tons. The Japanese had sufficient lift in 1941 and a tactical environment benign enough to move soldiers in conventional marus. By 1944, it had neither. So, approximately 2,000 men sailed aboard Musashi.

A departure from Japan in early March 1944 included troops and supplies loaded aboard a task group built around the aircraft carrier Zuikaku. The battleships Kongo and Haruna took aboard men, while the crew of the heavy cruiser Mogami wrestled aboard Army supplies. Later, the super battleship Yamato and heavy cruiser Maya loaded Army troops and equipment for a deployment to Manila in the Philippines. While the Yamato was involved in a redeployment for tactical purposes, the majority of these warships were tasked solely to move men and gear.

In late June, the largest logistics lift of the war to be transported in warships was assembled in Japan. It was a major fleet effort, which included no slow marus and only the fastest and best of Japan’s Navy. Speed and maneuverability were prized above all. Two heavy cruisers paved the way when they left Japan on July 1 headed for Manila. Both ships carried Army troops. The battleship Nagato took aboard matériel and a regiment of the 28th Division. The battleship Kongo took on men and supplies. A full regiment trooped aboard Yamato, more than doubling the number of men the ship was meant to hold. The crew of Musashi, the fourth battleship in this fleet, guided men and equipment into makeshift quarters. Ten cruisers took aboard troops and equipment. Seven destroyers rounded out the force, which left the Home Islands on July 8, dropped men off at both Okinawa and Manila, then headed south with the remainder of the troops and equipment. Three more cruisers left Japan on July 14 with reinforcements and supplies for Okinawa.

Heavy, light, and training cruisers executed 62 lift missions in 1944. Cruisers moved air base supplies, torpedoes, ammunition, antiaircraft units, Army troops, and Navy ground and air personnel. Losses during logistics runs in 1944 were only four light cruisers, three of which had unloaded their soldiers and were exiting the area. The losses equate to a 7 percent rate in lift assets and only 2 percent in cargo, very good considering how fatal it had been proven to move men in slower ships.

Hasty Logistics, Devastating Results

Throughout the war, the Japanese response when their ground forces were outnumbered and facing attack was to send in more troops and virtually ignore logistics. A large troop convoy assembled in Shanghai, destination New Guinea. The 32nd Division sent 12,874 men aboard four marus. The bulk of the 35th Division marched 8,170 men onto another four marus. Fifteen good-size marus left Shanghai on April 17, eight of which carried the two divisions.

A brief comparison of tonnage is in order. In January 1943, the Navy had moved the 20th Division from Korea to New Guinea in nine marus and two light cruiser transports, a total of 81,254 gross and displacement tons. Then from September to October 1943, the Navy had lifted the 17th Division using seven large marus, one naval auxiliary, and four light cruiser sorties. Gross registered tonnage and cruiser displacement totaled 91,073 tons. Now, in April 1944, for Convoy Bamboo No. 1 out of Shanghai, the Navy was lifting the majority of two divisions with eight marus and no cruisers, grossing only 45,687 tons. Overcrowding in 1944 was four times worse than in 1943, and that crowding invited disaster.

One reason that eight marus could carry two divisions was the lightness of the divisions. Japanese divisions lacked large logistics tails. In this case, lightness extended even into combat elements. The 35th Division had only two infantry regiments at Shanghai, the 220th and 221st. The division headquarters and the 219th Infantry Regiment were then in Japan and not part of this convoy.

The Japanese considered this an important lift. They assigned a rear admiral and the 6th Escort Convoy, consisting of a minelayer, three destroyers, three frigate-type escorts, one minesweeper, two subchasers, and three gunboats. Despite those 13 escorts, a U.S. submarine hit the 5,425-ton Yoshida Maru No. 1 and drowned an entire 32nd Division infantry regiment of 3,189 men.

The convoy put into Manila Bay on April 29, dropped off six Manila-bound marus, and detached five escorts. The convoy departed Manila on May 1. The ships now headed for Halmahera Island instead of New Guinea because Tokyo feared air attacks if the ships sailed any farther to the southeast.

A second submarine hit three of the eight transports. The ships stayed afloat long enough for most of the men to get off. Up to that time, the old transport Aden Maru (5,860 tons) had been a lucky ship. She had participated in several landings, dodged a torpedo, and survived a hit by a dud bomb. She was carrying 2,410 men of the 35th Division, and 700 of them died when the maru went down. Aside from a battalion of personnel lost, two more battalions went into the water and became survivors rather than armed combat units. The Taijima Maru (6,995 tons) sank. Down went the brand-new cargo ship Amatusan Maru (6,886 tons) sailing on her maiden voyage. She carried down 14 howitzers, and 95 of the 3,420 35th Division soldiers aboard were lost. The 35th Division, with two infantry regiments and an artillery regiment in this convoy, lost a battalion or more of infantrymen, all but a single battery of artillery, and equipment for two infantry regiments.

Had the Japanese operated with the normal supply and combat support tails standard in Western armies, they could never have transported 28 divisions, four division equivalents, and 41 brigade equivalents. In Western parlance, the corps and army troops could never have been moved. Even Japan’s combat divisions were light. The 62nd Division, activated in China in 1943 and shipped to Okinawa in 1944, did not have an organic artillery regiment and had miserably few engineers, signalmen, and trucks.

In 1941, the Army used 650,000 tons of shipping to move two combat-loaded reinforced divisions to the Philippines and 710,000 tons to move three combat-loaded reinforced divisions into Malaya. The Army estimated that it needed 1.5 million tons for the 12 divisions that were estimated to be required for the invasion of Australia in 1942. In February 1942, the Japanese had detailed 38 marus to move the reinforced 48th Division out of Luzon for an amphibious landing at Java. The March 1942 Christmas Island Seizure Force included two mid-size marus carrying just 850 men. The June 1942 Midway Transport Group boasted 100,000 tons of cargo ships, transports, and destroyer transports to carry just 2,450 Army and Navy infantry and two naval construction units. In 1944, 40,000 men would have stuffed themselves into Midway’s 100,000 tons.

Success with Heavy Losses

For 1944, the Army planned its movements on a merchant fleet reduced from the 1941 level of 6.1 million tons to a January 1944 total of roughly 3.8 million tons, a figure that would decline steadily during the year. It is true that administratively loaded units required much less tonnage than combat-loaded, invasion- ready troops. It is also true that 1944 deployments would extend over 12 months versus the single month of December 1941. That would allow the same ships to be used several times, or until they were sunk. But the distances were longer in 1944 than in 1941, and the enemy threat was vastly more dangerous.

Regardless, the Army succeeded. In the absence of modern technology, in particular adequate antisubmarine technology, the Japanese shoved men into the Philippines, Formosa, Okinawa, and the Marianas by brute force. Casualties did not matter, for raw manpower was the only coin left in the military’s purse. And the military spent it with reckless abandon. The military moved its men, but personnel and equipment losses were heavy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments