By Robert F. Dorr

Even today, they don’t like to talk about the St. Nazaire raid.

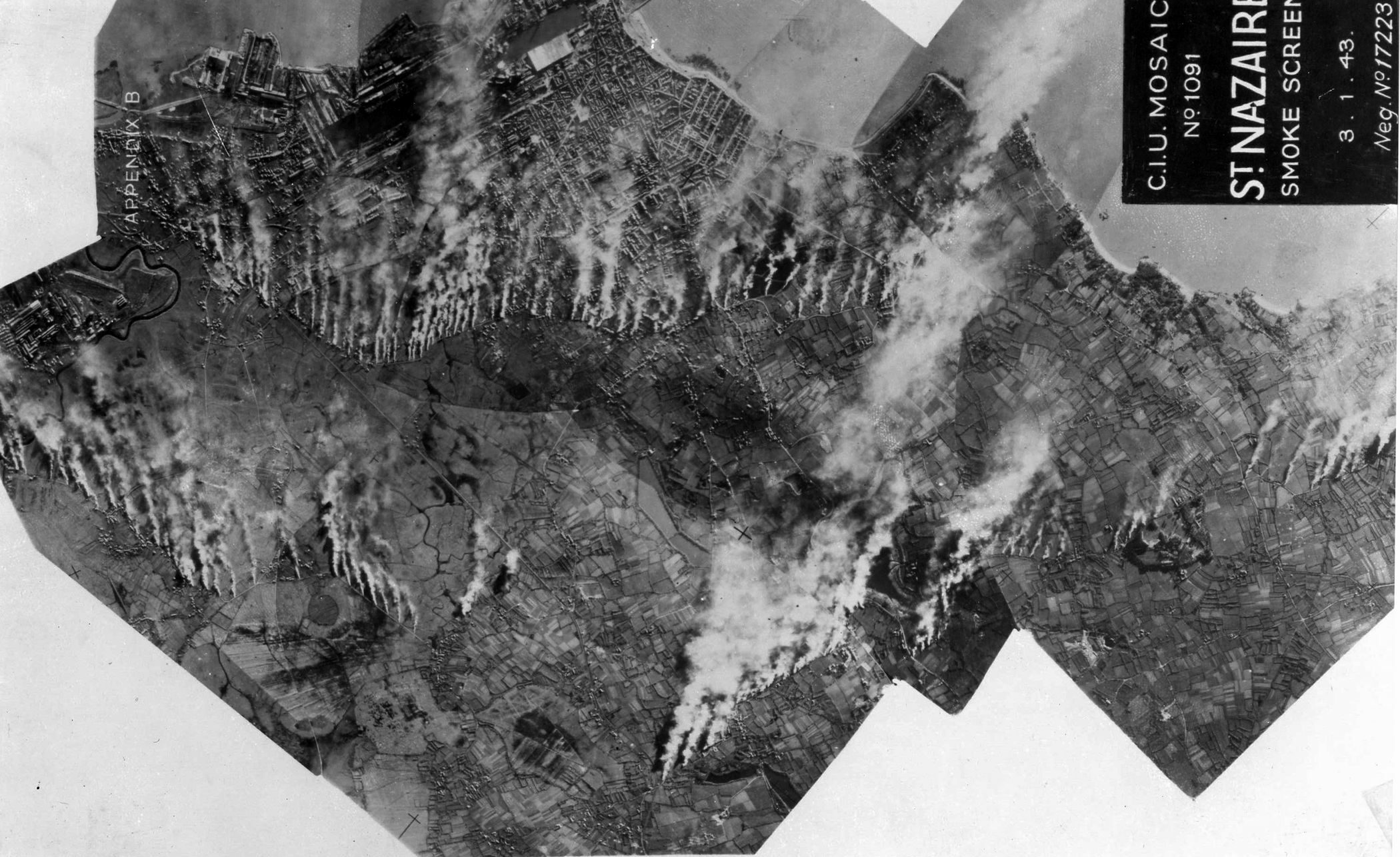

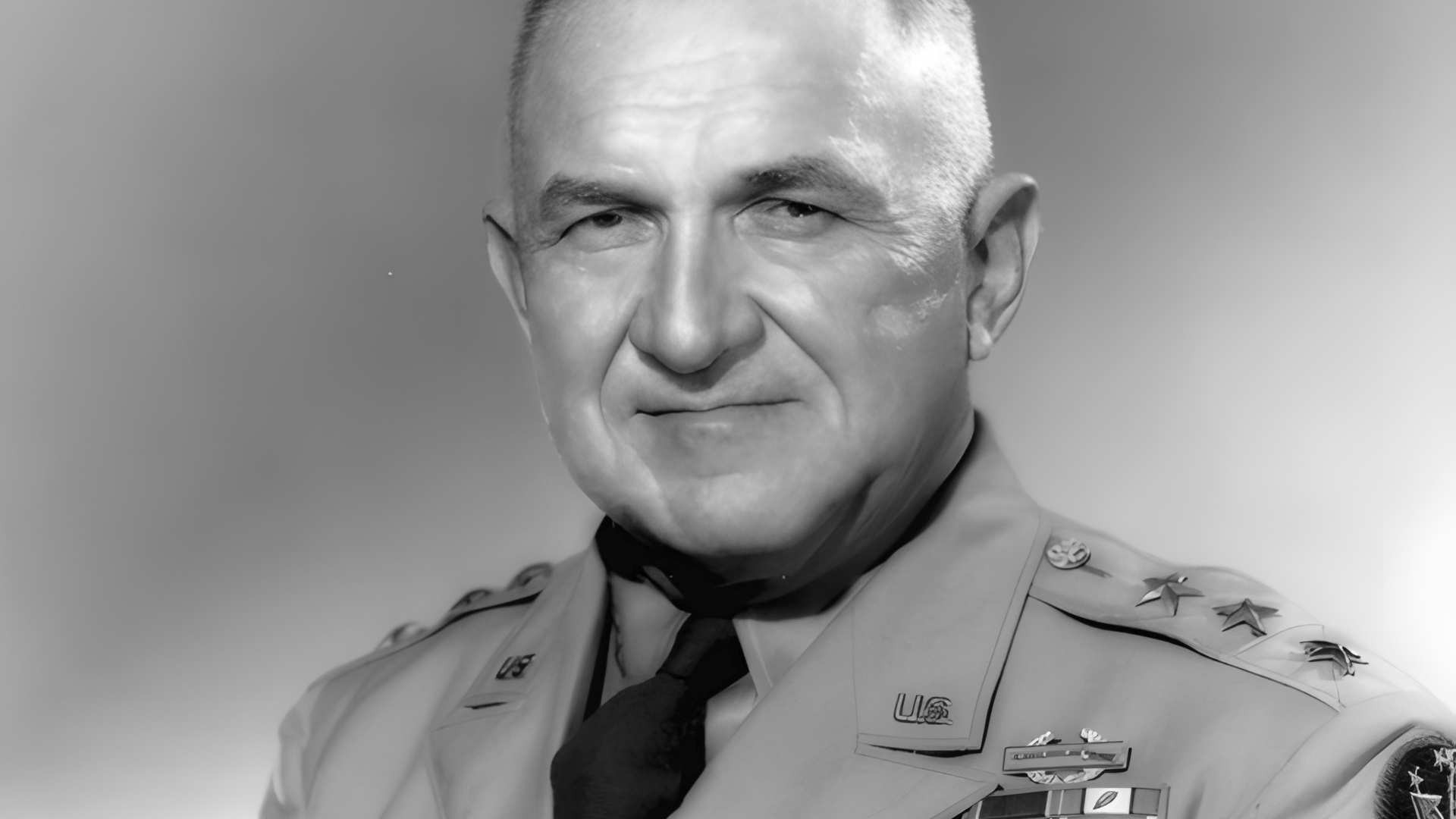

Compared to the thousand-plane raids that went deep into Germany later in World War II, the January 3, 1943, bomber mission from England to the coast of German-occupied France was small and spanned only a modest distance. It introduced new tactics from a leader who later made his mark by innovating aerial warfare. Yet Colonel Curtis E. LeMay’s attack on St. Nazaire ended up being mostly a debacle that appears to have had a high cost for achieving little.

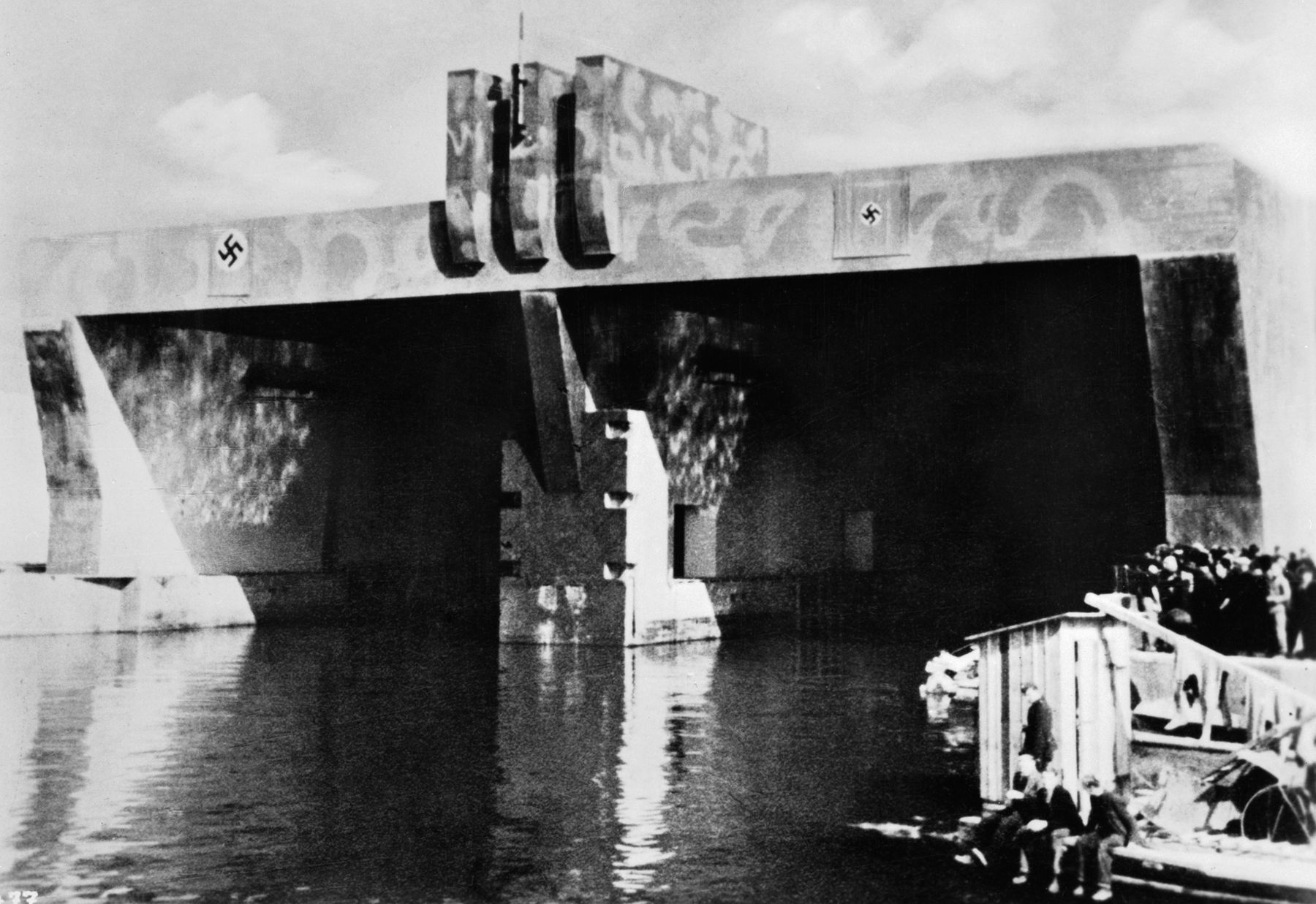

The purpose was to bomb the German submarine pens at St. Nazaire, which were dispatching the U-boats that were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. The Germans had U-boat pens at Lorient, La Rochelle, and Toulon in France and at Trondheim in Norway, and they were all difficult, heavily shielded targets for the new technique of massed daylight bombing, but none was more a challenge than the mammoth bunker base at St. Nazaire.

Britain’s Royal Air Force attacked St. Nazaire in February and March 1942 with Handley Page Halifax and Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers. Construction was only being finished then, and the pens might have been more vulnerable than they were later. Still, the Royal Air Force achieved mixed results, lost several aircraft to mishaps rather than German fire, and apparently did little to interrupt the savagery being inflicted on Allied shipping in the Atlantic by Admiral Karl Dönitz’s U-boat Rudeltaktik, or wolf pack strategy. Squadron Leader Michael Curphey, an RAF intelligence analyst, said in an interview for this article that his bosses concluded the U-boat pens were too heavily reinforced by concrete to be neutralized by bombing. Allied leaders believed, however, that they could hamper the U-boat campaign by bombing torpedo and optics facilities that were above ground.

“There was some disagreement between the British and the Americans on this,” said Curphey. “Frankly, the Americans went into the war overconfident in their daylight-bombing capabilities. We had plenty of experience with bombing by then and had chosen to do most of ours by night. The Americans eventually made daylight bombing work, but it’s debatable whether it ever worked against U-boat bunkers.”

The optimism felt by those early American bomber crews and their leaders may have been misplaced. After all, they lacked experience and were yet to learn the value, indeed the necessity, of fighter escort. Still, when LeMay, commander of the 305th Bombardment Group, who hung his hat at Chelveston in Northhamptonshire, led the attack on St. Nazaire, the mission was a landmark in the fledgling American daylight-bombing offensive.

“We learned a lot that day,” said former Sergeant Arnold Burton. A newly minted aerial gunner, he was manning a .50-caliber air-cooled machine gun in the waist position of a B-17F Flying Fortress (41-24482), called the Heavyweight Annihilators, of the 322nd Bombardment Squadron, 91st Bombardment Group. Burton was in a formation of 85 bombers that included 72 B-17s from the 91st, 303rd, 305th, and 306th Groups and 13 Consolidated B-24 Liberators from the 44th Group.

“Our aim point was a torpedo shed near the U-boat pens,” Burton wrote in a diary at the time. “Our bombload was five 1,000-lb. general purpose bombs. We took off at 9:12 am and were scheduled to return at 2:10 pm.” Burton’s 91st Group, nicknamed “The Ragged Irregulars,” was based at Royal Air Force Bassingbourn, located in Cambridgeshire about a dozen miles from Cambridge.

LeMay had experimented with various ways to stagger three- and four-plane elements so their defensive gunfire would have the most effect against fighters. He believed that the survival of a bomber crew battling winds, weather, and Germans depended in large measure on the performance of aerial gunners like Burton.

Burton was struggling with the faulty equipment and bad ideas that became part and parcel of the early days of the American daylight-bombing offensive over Europe. The problems resulted from flying higher and being colder than ever before in a combat aircraft. “The early, bladder-style oxygen mask didn’t work,” said Burton. “Your saliva would freeze up, and if you didn’t do something, you would pass out. So you had to jerk off the whole bladder and mask, pull the hose out of the mask, and stick the oxygen hose directly into your mouth and suck on it.” Later in the war, bomber crews would receive demand-type oxygen masks that worked.

Burton was irritated, even more, at the electrical suit designed to protect him from the terrible cold at high altitude. “Remember, the waist-gun position on the B-17F was just an open rectangle in the side of the fuselage,” said Burton. “Only much later, with the B-17G, did we have a window to keep the air from rushing in.”

“Heated boots and suits were constantly burning your ankles,” said Burton. “It was a terrible design. The suit was blue with wires all through it. The shoes that went into the boots were blue with an electric plug-in; the gloves that went inside your gloves were blue. You got cold, so you turned the rheostat up, and when you did that you’d start to burn at the wrists and the ankles. The suit literally burned you and sometimes it caught fire.”

Burton and the 91st Bombardment Group had a lot of aborts from guns freezing up. “You would chamber one round in your gun and be ready. When you were airborne, you were supposed to test-fire a couple of rounds. You’d shoot off one round and the gun would freeze.” Later in the war, there was a type of gun oil that didn’t freeze no matter how low the temperature.

What went into being a gunner in the early days of the bombing offensive? Burton was a product of the Midwest. Born in 1921 in Pella, Iowa, he took business classes in high school. He was doing office work, “not anything great, just menial office work,” when he learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Like many Americans, Burton did not at first recognize the term “Pearl Harbor” or know what place it referred to.

Burton enlisted and went through gunnery training at Lowry Field, Colorado, in 1942. “They had a P-37 fighter mounted on a rack with guns that fired two .30-calibers through the propeller,” Burton said. “We had to learn how to maintain and synchronize those guns. We had class where we assembled and disassembled various kinds of machine guns, rifles and pistols.” Initially a member of the 91st Group’s ground cadre (and only later a member of a flight crew), he went to war aboard the ocean liner Queen Mary and set up shop with the rest of his group at Bassingbourn. He was shifted to flight status. St. Nazaire was his third combat mission.

LeMay was nothing if not an innovator. He wanted his bombers to maintain a steady course during their bomb run, which began at an imaginary spot in the sky called the initial point and continued to the aiming point, a torpedo storage shed astride the St. Nazaire submarine pens.

In his book Flying Fortress, Edward Jablonski, without naming LeMay, described what LeMay wanted: “A new bombing technique was introduced on this mission which was to have an important effect upon future operations,” Jablonski wrote. “Instead of each plane dropping bombs individually, all bombardiers released when they saw the bombs leave the bomb bay of the lead plane. This technique resulted in greater accuracy (for the most skilled bombardier and pilot were in the lead aircraft) and a massive concentration of strikes in the target area.”

Still, even though studies showed that the odds of getting hit by flak went down if the bomber remained straight and level, crews didn’t like the new tactic. Burton’s pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Don C. Bader, did not like it. Burton’s bombardier, 2nd Lieutenant James W. Hensley, did not like it. Burton did not like it.

“The weatherman said we would have 90-mile-per-hour tailwinds,” said Burton. “He got it exactly wrong. We had 90-mile-per-hour headwinds.” An official record indicates that the bomber force was flying into an unprecedented, 115-mile-per-hour gale. Whatever the exact speed of the headwinds, they had the effect of slowing the bombers to a near-standstill in midair, meaning that the bomb run—the period when the crews went straight and level into German flak—lasted for what seemed an eternity.

Moreover, wrote Jablonski, “Instead of attempting to follow the formations as was the usual practice, the flak gunners introduced their own innovation. They predicted the area through which the B-17s would have to pass on the bomb run and filled that area with flak bursts. Three Fortresses were shot down over St. Nazaire [by flak] on that mission and dozens returned in various stages of damage.”

Burton said he did not feel the impact but “saw it happen” when a flak shell exploded near his B-17 and battered its No. 1, or right outboard, engine. “I saw the propeller get feathered and the smoke trailing back,” Burton said.

With LeMay in the lead, just 76 of the intended 101 Flying Fortresses actually found and hit the target. LeMay’s tactic called for a straight and level bomb run, flak or no flak, and the result was that seven bombers were shot down and 47 damaged.

German fighters made a belated attack on the B-17F of Staff Sergeant Alan Magee and shot off a section of the right wing, causing the aircraft to enter a deadly spin. Wounded ball turret gunner Magee leaped from the plane without a parachute. He rapidly lost consciousness due to the altitude.

Magee fell four miles. He crashed through the glass roof of the St. Nazaire railway station, which softened the impact of his plummeting body. German troops discovered Magee alive inside the station, took him prisoner, and administered medical treatment. He had 28 shrapnel wounds, several broken bones, severe damage to his nose and eye, and lung and kidney damage; and his right arm was nearly severed. Magee was liberated in May 1945 and received the Air Medal and Purple Heart.

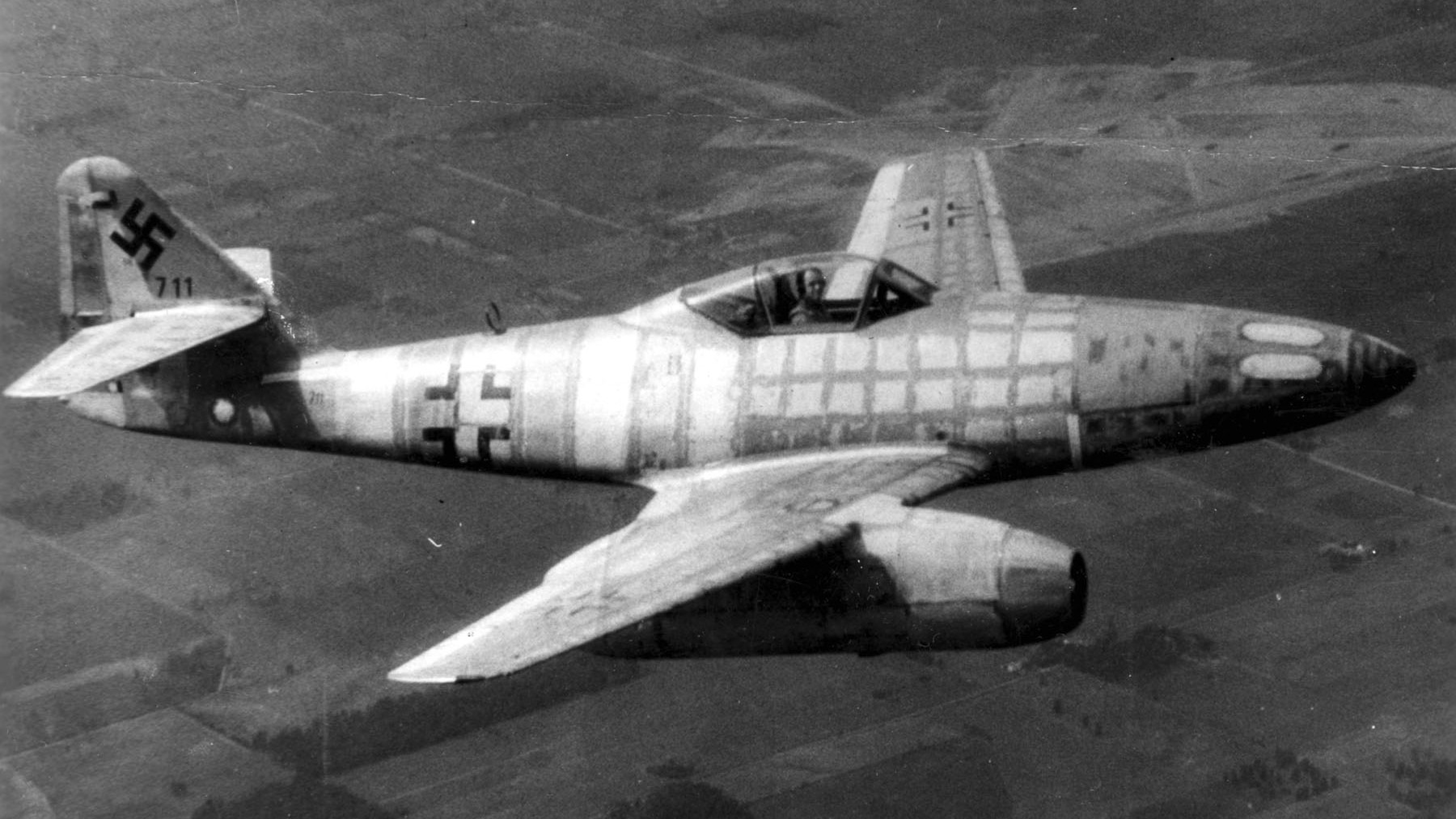

The bombers completed their runs, but German flak and fighters shot down three B-17s (of the seven lost altogether) as they emerged from the target. Burton said his bomber was swarmed over by Messerschmitt Bf-109 and Focke-Wulf Fw-190 fighters. He fired at them when he could, but by the time they crossed his gunsight, their work was done.

The Germans were using a new tactic of intercepting the bombers from above and head-on, striking from the position crews called “twelve o’clock, high.”

Coming off target the aircraft was hit by flak. One engine and wing caught fire. It lost speed and fell behind the group. Pilot Bader called the group leader over the command set but got no response. According to the after-action report, Captain Campbell, the leader of B Flight, whose first name is not recorded, heard “Heavyweight Annihilators in trouble” and made a 360-degree turn to pick them up. According to the report, Campbell’s gunners shot down two German fighters, and the remainder ceased swarming over Bader’s bomber.

Crewmen remember the situation differently. They got away from the target, all right. But as Bader struggled to nurse the damaged bomber over the English Channel, German fighter pilots saw the B-17 lagging and attacked it again. Gunfire wounded Bader and Hensley. In the air-to-air battle that ensued, two of the gunners aboard Heavyweight Annihilators—though not Burton—were credited with shooting down German fighters. In an after-action report, one wrote of “a Focke-Wulf hit by our slugs, pinwheeling and tearing itself apart with just a little fire and smoke.”

“With our wounded pilot struggling to keep us out of the water, we eluded the fighters and made a very rough landing at a British base in the south of England,” said Burton. “Our B-17 never flew again.”

Counting other bombers that made it home but were too damaged to fly again, total losses on the St. Nazaire raid were seven, according to official records. German records indicate that the Luftwaffe claimed 15 bombers destroyed by fighters although fighters were actually responsible for four of the seven.

Historians disagree whether this attack on concrete-reinforced submarine pens, or any other, had much impact on the Battle of the Atlantic, where German U-boats wreaked havoc on Allied convoys. Early in the aerial campaign against Germany’s submarine bases, Allied air commanders decided they would not be able to penetrate the concrete bunkers that protected the U-boats but believed they could achieve the same purpose by targeting the adjacent torpedo depots that were above ground.

What the January 3, 1943, raid on St. Nazaire proved indisputably was the flaw in the idea that the “bomber will always get through”—at the core of Army Air Forces doctrine. At great cost, and all too slowly, it was being learned that bombers needed fighter escort to get through. Two years later, as the end of fighting in Europe approached, the long-range North American P-51 Mustang escort fighters commanded the sky all the way from bomber takeoff to target. By then, Luftwaffe fighters were no longer a serious threat to B-17s or B-24s. The cohort of aerial gunners that followed Burton by a year or two often flew 30 missions without ever firing their machine guns at a German aircraft.

LeMay (1906-1990) became the leading bomber general of his era, introduced new tactics repeatedly up through the firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945, reached four-star rank, and was Air Force chief of staff from 1961 to 1965. Hensley (1920-2000) became a beer distributor and was the father of Cindy McCain, wife of Senator John McCain, R-Arizona. Burton, 86, flew 46 combat missions and lives today in St. Charles, Illinois.

Robert F. Dorr is a U.S. Air Force veteran, a retired diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, a look at presidential aircraft and air travel.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments