By Victor Kamenir

Soviet machine-gunner Mykhailo Petrik and his platoon comrades lay in their makeshift bunker on the open steppe land 30 miles northwest of Belgorod awaiting the enemy’s advance on the first day of the titanic clash at Kursk. He and his comrades were situated in the path of XLVIII Panzer Corps of German Army Group South. Petrik was armed with a 7.62mm gas-operated DP-27 Light Machine Gun. With its pan magazine perched on top, it was light enough to fire from a hip but had far greater accuracy when fired from a bipod.

“We were targeted by dive bombers, artillery, and tanks,” he recalled years later. “But then it stopped as the [German] infantry rushed forward, and was replaced by the drilling sound of German machine guns and the explosion of mortars.” With their ammunition and grenades in easy reach, Petrik and his fellow soldiers braced themselves for a fight with the veteran German infantry that followed the German panzers and tank hunters. “We did not expect to survive, and we knew death was arriving, and I could not catch my breath,” he recalled. When the German infantry reached them that day, they would experience a firefight like never before.

After the Russian offensives known as operations Star and Gallop in winter 1943 and the German counteroffensive known as the Donets Campaign in February 1943 had run their respective courses, an operational pause settled over the Eastern Front. When active operations on the front died down in March, a large Soviet salient developed around the city of Kursk, which was situated 325 miles south of Moscow. This bulge was sandwiched between smaller German salients at Orel and Belgorod-Kharkov.

Beginning in March 1943, each side began planning for its summer campaign. The German Wehrmacht, which was deeply concerned about a possible Allied invasion of Western Europe, planned a limited offensive by which they would seek to reduce the Kursk salient. Codenamed Operation Citadel, the German plan called for a pincer strike against the base of the salient. The main objective was to encircle and destroy the Russian forces trapped within.

The German initially scheduled their offensive for early May, but they postponed it several times because of difficulties encountered in assembling enough troops, vehicles, and supplies for the offensive. This proved to be a major challenge, for many units were depleted as a result of previous campaigns on the Eastern Front. Despite their best efforts, the German divisions earmarked for the operation averaged just 80 percent of their nominal strength on the eve of the campaign.

German leader Adolf Hitler met with his senior commanders in Munich on May 4 to discuss the plan for Operation Citadel. Hitler and his generals could not achieve a consensus. Some of the field commanders favored the offensive, while others did not. Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, the Inspector General of Armored Troops, and Albert Speer, the Minister of Armaments, were both against the offensive. They feared a major battle against the best forces of the Soviet Union would result in a catastrophic loss of panzers. Moreover, they held that the Wehrmacht could not afford the possible loss of hundreds of tanks with an Allied invasion of Western Europe looming on the horizon. Hitler ordered the offensive to proceed regardless of their objections. He scheduled it for July 5 to allow enough time for newly produced armored vehicles to reach the panzer divisions at the front.

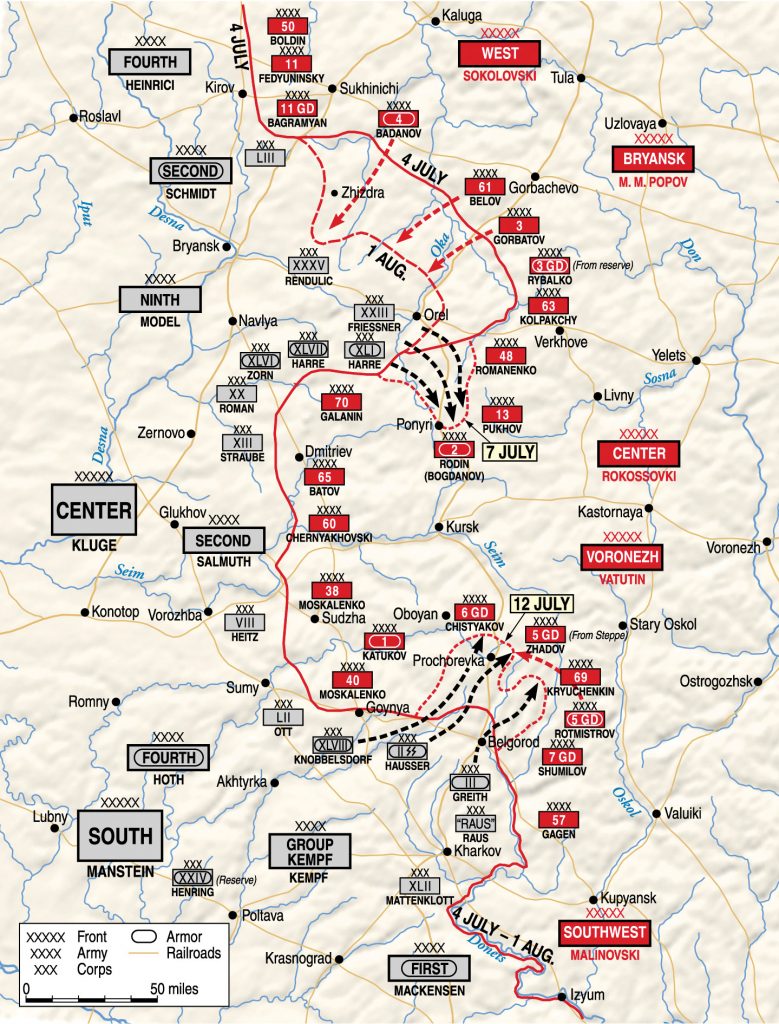

The German plan called for Generaloberst Walther Model’s Ninth Army of Army Group Center to strike south from Orel, while Generaloberst Herman Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army and General der Panzertruppe Werner Kempf’s Detachment of Army Group South would attack north from the Belgorod-Kharkov sector.

While Model and Hoth would spearhead the main pincer attacks, Generaloberst Hans von Salmuth’s Second Army of Army Group Center would launch a heavy diversionary attack to pin down Russian forces along the western face of the salient.

If the Germans succeeded in destroying the Soviet forces in the Kursk salient, they would have an opportunity to follow up their victory in one of two ways. In one possible scenario, they could swing north from Orel to carry out a deep encirclement of Moscow. In another scenario, they could turn south to encircle the Soviet forces deployed along the Donets River.

To crush the Soviet forces in the Kursk salient, the Germans planned to mass their armor. The Germans fielded an impressive array of new armored fighting vehicles for the campaign. Their newest panzers were the medium Panzer V Panther and the heavy Panzer VI Tiger. The Nashorn and Elefant, new tank destroyers armed with 88mm cannon, would furnish additional mobile firepower. Lending their firepower from the rear of the advancing forces would be two new self-propelled howitzers, the Wespe and Hummel, which mounted, respectively, the 105mm and the 150mm main guns.

Altogether, the Germans would have 900,000 troops, 2,700 tanks and assault guns, thousands of artillery pieces and mortars, and 2,000 combat aircraft for Operation Citadel. Each side had approximately 2,000 combat aircraft.

Having gained invaluable experience fighting the Germans for the past 24 months, the Soviet High Command, known as Stavka, planned in early 1943 a far-ranging offensive that would crush German army groups Center and South; and in so doing, liberate left-bank Ukraine. The liberation of the region was of critical importance, for its Donbass area was rich in natural resources needed for the Soviet war effort. The envisioned offensive would involve several Soviet fronts (the rough equivalent of German army groups) deployed in the center of the Soviet line on the Eastern Front.

Like the German high command, Stavka also experienced strong differences of opinion regarding whether it was best to remain on the defensive or switch to the offensive in summer 1943. Unlike Adolf Hitler, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin deferred at that stage of the war to his senior commanders’ opinions while maintaining overall authority.

Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who was the Soviet deputy supreme commander, believed that the Red Army should remain on strategic defensive and only attack after the Germans had exhausted themselves. “I consider it inexpedient for our forces to go on the offensive in the coming days in order to forestall the enemy,” he wrote after the war. “It would be better if we exhaust the enemy on our defenses, knock out his tanks, and then, by introducing fresh reserves and going on a general offensive, we will decisively finish off the main enemy group of forces.”

Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky, the Soviet Chief of the General Staff, agreed with Zhukov. Although Stalin and some of his aggressive front commanders favored an offensive in the early summer to keep the Germans off balance and regain territory lost to the Germans in the Donets Campaign counteroffensive, he eventually saw the wisdom of strategic defensive that would lay the groundwork for the counterstrokes that would follow.

Members of the General Staff therefore began not only drawing up plans for the strategic defensive, but also for two counteroffensives that would follow the battle once the German forces had exhausted themselves. A planned northern counteroffensive codenamed Operation Kutuzov would seek to destroy German forces in the Orel bulge, while a southern counteroffensive codenamed Operation Rumyantsev would seek to crush German forces in the Belgorod-Kharkov bulge.

General Konstantin Rokossovsky’s Central Front defended the northern half of the salient, and General Nikolai Vatutin’s Voronezh Front defended the southern half. General Ivan Konev’s Steppe Front deployed behind the two fronts as the reserve. Stalin dispatched Zhukov to oversee the operations of the Central Front, and he tapped Vasilevsky to do the same for the Voronezh and Steppe fronts.

In April Soviet forces within the salient began fortifying its 340-mile-long perimeter. Combat engineers directed the construction of mine fields, barb-wire emplacements, and antitank ditches. To prevent the Germans from achieving a blitzkrieg breakthrough, the Soviets planned a defense in depth consisting of seven fortified belts. The defenses were 190 miles deep and included 2,600 miles of trenches.

The combat engineers oversaw the construction of some of the most formidable defenses along likely axes of advance. In these sectors, they planned additional anti-tank ditches and anti-tank strongpoints. Armored and mechanized units deployed to support the anti-tank strongpoints.

Taking into account the concentration of German forces south of Orel, senior commanders of the Central Front believed the main German effort would most likely unfold along the Olkhovatka-Ponyri axis of advance. Accordingly, Rokossovsky’s forces intended to focus heavily on obstructing German progress through this corridor. The Central Front fielded 700,000 men, 1,607 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 11,000 artillery pieces and mortars.

Vatutin’s Voronezh Front defended the southern face of the salient. Expecting the main German threat to come from Belgorod, the general concentrated his main strength on his left flank. The Voronezh Front fielded 625,000 men, 1,700 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 8,500 artillery pieces and mortars.

Konev’s Steppe Front was tasked with plugging any German breakthroughs, furnishing reserves as needed to the other two fronts defending the frontline, and being ready to conduct counterattacks as needed. Konev had under his command 573,000 men, 1,630 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 9,000 artillery pieces and mortars.

Model’s Ninth Army faced the Central Front. It was organized into 22 divisions, of which six were armored and one was mechanized. Generaloberst Walter Weiss’s Second Army, which had seven infantry divisions, would support the Ninth Army. Model concentrated the bulk of his forces on a 40-kilometer-front opposite the Soviet 13th Army and right flank of the 70th Army.

Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army and Kampfgruppe Kempf faced the Voronezh Front. They fielded a combined total of 24 divisions, among which were eight armored and one motorized.

The Soviets enjoyed numerical superiority in men and materiel. Moreover, they had sufficient quantities of reserves to conduct offensive operations.

Despite German attempts at deception in spring 1943 in the weeks leading up to Operation Citadel, the Soviet command knew that the offensive would start the first week of July. On the evening before the attack, Soviet intelligence confirmed that it would unfold on July 5.

German battalions began reconnoitering Soviet positions on July 4. The aggressive German units probed enemy defenses and drove back Soviet forward outposts in preparation for the morning attack. Under cover of darkness, German combat engineers carefully began removing Soviet mines that lay in the projected path of the attacking forces.

Several German prisoners captured on July 4 said that the attack would come at dawn. With this information in hand, both Zhukov and Vasilevsky authorized pre-planned artillery strikes. The Soviet heavy guns began shelling German positions at 1:10 am and continued firing for little over an hour.

Despite massive expenditures of ammunition, the Soviet artillery strikes had little effect on the combat capabilities of German panzer and infantry forces. Red Army intelligence units had failed to identify German pre-attack staging areas, and the artillery bombardment began prematurely, while the Germans were still in their shelters.

In many cases, therefore, the Soviet artillery strikes were not sufficient to disrupt German preparations. German units suffered only minor losses and re-formed up for battle with virtually no difficulty. Meanwhile, Soviet ground-strike aircraft dispatched to bomb German airfields ran headlong into swarms of German fighters and heavy antiaircraft fire. Thus, the Soviet air strikes were also largely ineffective.

The German Ninth Army attacked after conducting an artillery bombardment and air strikes at dawn. Model’s strategy for breaking through the Soviet defensive belts called for his infantry divisions to make the first strike. Heavy tanks and assault guns, supported by artillery and aviation, followed on the heels of the infantry. After the panzer divisions punched through the Soviet defenses, they had orders to push on in the direction of Kursk.

Generalleutnant Joachim Lemelsen’s XLVII Panzer Corps, reinforced by 505th Heavy Panzer Tiger Battalion and two Stug. III assault-gun battalions, constituted the armored punch of the Ninth Army’s attack. Generalleutnant Hans Zorn’s XLVI Panzer Corps, reinforced by a regiment of Elefants, advanced on its left.

Lemelsen’s troops attacked all along the 30-mile front of the Lt. Gen. Nikolai Pukhov’s 13th Army and the adjoining flanks of the 48th and 70th Armies. The XLVII’s main push struck the left flank of the 13th Army in the direction of Olkhovatka.

Throughout the day, German panzer divisions acted like a giant battering rams. The Tiger tanks advanced in the vanguard. Their thick frontal armor sheltered the medium and light tanks, assault guns, and self-propelled artillery that followed behind them. In some places the Soviet infantry fell back, but the integrity of Soviet defenses remained intact. The vaunted Tiger tanks failed to make an impression on Soviet defenses, largely because Rokossovsky continually fed reserve units into the fray.

During the first day, the Germans penetrated the defenses of the 13th Army up to six miles, but they were brought up short of Olkhovatka. Unable to break through at Olkhovatka, the Germans shifted toward Ponyri, a strongpoint in the second line of Soviet defenses located astride a highway and a railroad line Orel-Kursk. The XLVI Panzer Corps reached Ponyri but was also unable to break through. While the ground fighting raged, hundreds of aircraft from both sides swarmed over the battlefield.

“When our squadron arrived above the front line, the sky was already crammed, and more and more German aircraft were approaching the battlefield,” recalled Ivan Kozhedub, a Soviet fighter pilot. “At the [time] there were 250 to 300 aircraft. Flying in separate groups, the Germans formed a multi-tiered battle formation.”

Kozhedub said that the Stuka dive bombers were at the bottom of the multi-tiered air formation, diving on targets from 1,500 meters. Detachments of Focke-Wulfs raced through the sky above them. In dense formations above the Focke-Wulfs were twin-engined Junkers-88s fast bombers and twin-engined Heinkel-111 medium bombers. Flying patrol for the twin-engined bombers were the latest versions of the Messerschmitt fighters.

“This whole armada of enemy aircraft was heading east to break through our air patrol line,” Kozhedub continued. “Its purpose was to strike at our defenses and thereby clear the way for its ground forces.”

The advance of the XLVII Panzer Corps in the direction of Olkhovatka renewed in the morning of July 6, landing a hard blow on the 15th Rifle Corps of the 13th Army. Heavy fighting flared up for Ponyri, as well.

The Germans “failed to suppress the resistance of our 75th Division,” Lt. Gen. Ivan Liudnikov, commander of the Soviet 13th Rifle Corps, wrote afterwards. “Sending in new tanks, changing the direction of the attack on the move, they tried to bypass the village of Buzuluk. We responded to this enemy maneuver with one of our own: enemy tanks were met with fire from two antitank regiments from corps reserve.”

The fighting raged for three hours, according to Liudnikov. The Soviets succeeded during the savage encounter in knocking out 35 German tanks. He said that although there was plenty of time left in the afternoon, the Germans halted their attack for the day after sustaining considerable losses.

At the same time, Rokossovsky ordered the 17th Guards and 18th Guards Rifle Corps, as well as 2nd Tank Army and 19th Tank Corps, to counterattack. But due to poor coordination, only the 16th Tank Corps of the 2nd Tank Army, which had 200 tanks, went into action against the Germans.

The 16th Tank Corps ran headlong into the Tiger tanks of the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion. Instead of probing for the flanks of the advancing Germans, the Soviet tanks launched a frontal assault. It proved a bad idea, for the Tigers’ 88mm gun and thick frontal armor gave the Germans a distinct advantage. Having lost 69 tanks, the 16th Tank Corps fell back to positions of the 17th Guards Rifle Corps in the area of Olkhovatka.

During the next three days, beginning on July 7, the Ninth Army battled for Ponyri and Olkhovatka. The Germans succeeded on the first day in capturing part of Ponyri after hard fighting, but they were ejected from the village the next day by fresh Soviet reserves.

The savage fighting at Ponyri and neighboring Hill 253.5 devoured men and machines on both sides. A particularly strong push on July 10, which was delivered by large numbers of German tanks and assault guns, failed as well. The farthest German penetration of the 13th Army’s defenses was eight miles, and it was achieved at an appalling cost. Model switched to the defensive the following day.

On the southern face of the salient, Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army went on the offensive on July 5. Generalleutnant Otto von Knobelsdorff’s XLVIII Panzer Corps and SS Senior Group Leader Paul Hausser’s II SS Panzer Corps attacked toward Oboyan with their Tiger tanks leading their attack. In an attempt to establish bridgeheads across the Psel River, XLVIII Panzer Corps unleashed a powerful attack northwest of Belgorod against the 22nd Guards Rifle Corps of Lt. Gen. Vasily Chistyakov’s 6th Guards Army.

Facing withering direct artillery fire, the Germans also had to contend with the numerous muddy streams and marshes that crisscrossed the area. A regiment of Panther tanks of Generalleutnant Walter Hornlein’s Grossdeutschland Panzer Grenadier Division became hung up for a time when it ran headlong into minefields. Even though by day’s end the XLVIII Panzer Corps had torn a three-mile gap in the first line of the Soviet defenses, their second line of defenses remained intact.

On the right flank of the XLVIII Panzer Corps, Hausser’s II SS Panzer Corps advanced against Chistaykov’s 23rd Guards Rifle Corps. Soviet defenders disputed every inch of ground, but by nightfall the leading Tiger tanks had succeeded in penetrating up to 12 miles into the first line of Soviet defenses. Still, the Soviet second line held fast.

On the right flank of the Fourth Panzer Army, Kampfgruppe Kempf attacked in the direction of Korochi. It fell to Lt. Gen. Mikhail Shumilov’s 7th Guards Army to check the assault.

Generalleutnant Hermann Breith’s III Panzer Corps had made a wide and deep penetration of Soviet defenses by the end of the day on July 5. The Panzer troops had sliced a four-mile-wide breach in the Russians’ first defensive belt, but the panzer troops’ advance ground to a halt at the Soviet second defensive belt. Vicious fighting occurred as the tenacious German panzer troops engaged their Soviet counterparts. All the while, German bombers pounded the Soviet defenses.

Upon Vatutin’s orders, General Mikhail Katukov’s 1st Tank Army, which was composed of two tank corps, together with the 2nd Guards and 5th Guards Tank Corps, took up supporting positions behind Chistyakov’s hard-pressed forces.

Machine-gunner Petrik’s account of his experiences at Kursk is a good example of the hard fighting conducted by infantry forces on both sides. Petrik and his fellow platoon members fought tenaciously against the Germans on the first day of the battle. Although he knew from experience that his DP-27 light machine gun was prone to overheating, he found himself firing it as fast as possible to fend off his attackers.

His platoon kept the Germans at bay for a time, until the intrepid Germans began pounding their trenches with mortar fire. Knocked unconscious by the mortars, Petrik came to that night long after the Germans had swept past their position. His partner lay dead next to him.

“Clearly the Germans had passed by thinking us both dead.” That evening he walked north over the battle-scarred steppe and reached the safety of Soviet lines, where he proceeded to collapse from a shrapnel wound to his neck. Despite his debilitating injury, he would survive the battle.

That night, Katukov received orders to conduct a counterattack on the morning of July 6. He proceeded to carry out his orders, although he had serious reservations about the ability of Soviet tanks to go toe-to-toe with the newly fielded German tanks and tank hunters.

“It was no secret that the 88mm guns of the Tigers and Elefants could pierce the armor of our tanks from the distance of two kilometers,” he said afterwards. “It is unlikely that in this case our T-34s will be able to win a tank-on-tank fight, but the enemy heavy tanks also have a drawback, which is poor maneuverability. This flaw [could] be perfectly exploited from ambushes.”

His fears came true. When the 1st Tank Army engaged the German heavy tanks on July 6, it suffered heavy tank losses. “Already the first reports from the battlefield near Yakovlev showed that we were doing the wrong thing,” Katukov said. “As expected, brigades suffered heavy losses. With heavy heart, I saw from the observation post the burning and smoking T-34s.”

Throughout the day, the XLVIII Panzer and II SS Panzer Corps tried to batter their way to Oboyan. “It was half past four in the afternoon, but it felt like a solar eclipse,” Katukov recalled. “The sun disappeared behind clouds of dust. And ahead, in the twilight, flashes of shots were visible, the earth crumbled, engines roared and tanks clanged.”

The German counterattack decimated the 5th Guards Tank Corps of the 1st Tank Army. Soviet commanders called off a counterattack when the Germans succeeded in penetrating the second defensive belt in several places where it was defended by the 6th Guards Army.

The XLVIII Panzer and II Panzer Corps linked up at the end of July 6. Their combined presence posed a palpable threat to Soviet forces at Oboyan. With some serious gaps finally beginning to appear in the Soviet second defensive belt, Vatutin kept feeding fresh tank and antitank-artillery regiments into the fray to shore up the deteriorating defenses.

At first light on July 7, the Germans continued their advance towards Oboyan. To reach their objective, they battled elements of the 1st Tank Army, 2nd Guards Tank Corps, and 5th Guards Tank Corps, as well as various depleted infantry divisions. Despite being punctured in several places, the second defensive belt remained largely intact.

“The fighting was ferocious, death roamed the battlefield, but there was no panic. For the first time we met the notorious Tigers,” wrote Evgeniy Ivanovskiy, the chief of intelligence for the 2nd Guards Tank Corps. “Their shells, fired from distances exceeding capabilities of our T-34s, presented a threat to T-34’s armor. Our crews quickly adapted to operate against the Tigers by maneuvering to hit their side armor, tracks, and other vulnerable spots.”

Ivanovskiy said he saw a destroyed Tiger that had succumbed not to Russian tanks, but to being “pecked to death by infantry.” He said there were numerous dents in the destroyed tank. The death blow to the Tiger had come in the form of an antitank munition that had struck the engine compartment and set the iron behemoth on fire. “Destroyed Tigers emitting black smoke were scattered everywhere tank battles took place,” he said.

Hoth’s Fourth Panzer Army and Kampfgruppe Kempf continued their push along the Belgorod-Oboyan highway. For the next three days the Germans attacks were met by savage Soviet counterattacks. The death toll mounted steadily on both sides.

Field Marshal Von Manstein chose a new path of attack when his forces were unable to break through the Soviet defenses in front of Oboyan. He shifted his axis of advance 20 miles southeast towards the village of Prokhorovka.

When Vatutin discerned Manstein’s maneuver, he sent the 69th Army and the 35th Guards Rifle Corps to Prokhorovka. To assist the hard-pressed Voronezh Front, Stavka issued orders to Steppe Front General Ivan Konev to commit his three armies, as well as the 5th Guards and 5th Guards Tank armies, to the spreading battle. Stavka also instructed Vatutin to stage a large-scale counterattack on July 11 using five of his six armies.

But Soviet plans for a counterattack were disrupted when the Germans captured the areas where the Soviets intended to stage their forces. Only by committing four rifle divisions and two tank brigades from Lt. Gen. Pavel Rotmistrov’s 5th Guards Tank Army were the Soviets able to halt the advance of the German forces, less than two miles from Prokhorovka. The engagement at Prokhorovka was about to begin.

By the end of July 11, the II SS Panzer Corps, which was deployed northeast of Yakovlevo, was ready for the renewed push to Prokhorovka. All three of Hausser’s veteran SS panzergrenadier divisions had been well-rested and well-equipped on the eve of the campaign. In the center of German dispositions was the 1st SS Panzergrenadier Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler. The SS troops of Leibstandarte entrenched during the night. The tank crews placed their Tigers in a hull-down position so that only the turret was exposed. Their line was studded with antitank artillery.

The 1st SS Panzergrenadier Division advanced that morning in the center, with the 3rd SS Panzergrenadier Division Totenkopf and 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Division Das Reich, respectively, on its left and right. The three SS Panzergrenadier divisions numbered 292 tanks and 58 assault guns. Only 15 of their tanks were Tigers, though. The III Panzer Corps from Kampfgruppe Kempf, which was to attack toward Prokhorovka from the south, had 100 tanks and 19 assault guns. Thirty of its tanks were Tigers.

The Soviet plan of attack at Prokhorovka called for the three Guards armies and two tank armies to destroy the II SS Panzer Corps; however, the bulk of these forces became bogged down in defensive fighting. They were therefore unable to launch a concerted counterattack that day as planned.

On the morning of July 12, a 15-minute Soviet artillery barrage began the largest tank battle in history. Soviet armored forces at Prokhorovka numbered 789 tanks and 37 self-propelled guns. With their engines revving, the Soviet armor lumbered menacingly towards Yakovlevo that morning. Advancing on a narrow, six-mile front were a rifle corps from the 5th Guards Army, two tank and one mechanized corps from the 5th Guards Tank Army, and the 2nd Tank and 2nd Guards Tank Corps.

By that time, though, the Germans already were on the move. They met the Soviet forces head on. The heaviest fighting took place west of Prokhorovka. In this sector, the main body of the 5th Guards Tank Army clashed with the II SS Panzer Corps and Generalleutnant Walter Schilling’s 17th Panzer Division, brought up from Manstein’s reserve. A second clash flared up in the area of Rzhavets, 10 miles southeast of Prokhorovka. In that fight the 5th Guards Tank Army squared off against Breith’s III Panzer Corps of Kampfgruppe Kempf.

“It turned out that the Germans and we went on the offensive at the same time,” Rotmistrov wrote. “I was surprised at how close to each other ours and enemy tanks were gathering. Two huge tank avalanches were moving toward each other. The sun rising in the east blinded the German tankers and brightly illuminated the outlines of the fascist tanks for us.”

As the two armored waves drew closer to each other, the qualitative edge of German tanks quickly became apparent. The German guns, which had a longer reach, began knocking out tanks from the advancing Soviet formations.

Armor-piercing shells from the Tigers’ 88mm guns could easily defeat the T-34’s 45mm frontal armor at ranges of up to 2,000 meters, while long 75mm gun on the Panzer Mark IV could achieve the same results at up to 1,500 meters.

Painfully aware of their vulnerability, the Soviet tank crews hurried to close with the Germans. The T-34s needed to come to within 1,000 meters for their 76mm guns to be effective against a Panzer Mark IV and much closer to have a chance against a Tiger. The Soviet crews of the T-70 light tank, with its 45mm gun, and the British Lend-Lease Churchill III tank, with its 57mm gun, had to be practically on top of the lighter German tanks in the second echelon to knock them out.

The two onrushing formations collided and their tanks became intermixed. Artillery crews on both sides held their fire for the fear of hitting their own armored vehicles. “The battlefield was swirling with smoke and dust and the ground shook with powerful explosions,” Rotmistrov wrote. “The tanks crashed against each other and, grappling, could no longer disengage, fought to the death until one of them burst like a torch or halted with broken tracks.”

Rotmistrov said that the crews of the disabled Soviet tanks, if their main guns were still operational, continued to fire on the Germans. The tanks circled around as if caught in a giant whirlpool, he recalled. “The T-34s, maneuvering, dodging, shot Tigers and Panthers, and were dying themselves, disabled, burned, falling to direct hits from enemy tanks and self-propelled guns,” he wrote. “Shells ricocheted off armor, tracks were torn to pieces, rollers blew out, and explosions inside the machines tore off and flung aside tank turrets.”

Unable to reach Prokhorovka head on, the Germans committed the reserve 11th Panzer Division from the XLVIII Panzer Corps. The 11th Panzer Division bypassed the right flank of the 5th Guards Tank Army and crashed into the flank of the 33rd Guards Rifle Corps. By early afternoon the enemy tanks were able to punch through the Soviet defensive positions and reached the area of Veselyi-Polezhayev, but their attack was blunted by Rotmistrov’s reserve 5th Guards Mechanized Brigade.

After neutralizing the new threat, Soviet tanks began pushing the Germans to the south. The Germans gave up ground grudgingly, counterattacking at every turn, forcing Rotmistrov to halt his offensive by the evening. After the day of incredible carnage, neither side accomplished its mission. The Germans were not able to break through to Prokhorovka to break into operational maneuver space. In turn, the Soviets were not able to destroy the II SS Panzer Corps in the vicinity of Yakovlevo.

The Allied invasion of Sicily, which had begun shortly after the battle began, distracted the German High Command. Hitler flew to confer with Manstein and Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, the commander of German Army Group Center, on July 13 to discuss halting Operation Citadel. With the Ninth Army temporarily unable to continue offensive operations, Von Kluge suggested withdrawing to the starting line; however, Manstein advocated a continued advance of Army Group South towards Kursk. But when the Red Army launched its Mius–Donets offensive on July 17, the Germans abandoned any further offensive operations.

Soviet forces also went on the offensive further north. The previous day, just as the fighting at Prokhorovka had begun in earnest, Soviet forces in the northern sector of the Kursk salient launched their pre-planned offensive known as Operation Kutuzov. Conducted by the forces of the Western, Bryansk and Central fronts, their objective was the destruction of the German forces at Orel.

By the end of the day on July 13, the Red Army had succeeded in breaching the German defenses. On July 26 the Germans began to withdraw their forces from the Orel salient. Even though the German Second Panzer Army and Ninth Army had been bled dry, they remained intact and retreated to a second line of defense east of Bryansk. Jubilant Soviet forces entered Orel on August 5.

In the south, the Voronezh and Steppe fronts switched over to the offensive on July 18. Their offensive operations heated up in early August with the formal launch of Operation Rumyantsev, which had as its goal the elimination of the German salient at Belgorod-Kharkov. The Red Army captured Belgorod on August 5, the same day it occupied Orel. Soviet forces liberated Kharkov on August 23; this achievement marked the end the Battle of Kursk.

Even though the Soviet forces achieved minor penetrations in German defensive lines at Orel and Belgorod, they were not able to break through and push back the Germans. Entrapping and destroying German formations was not something the Red Army would be able to achieve until later in the war. The Germans were masters of defensive fighting. In reality, the Red Army experienced the majority of its losses during the Battle of Kursk once it switched to the offensive.

It is difficult to arrive at accurate numbers of casualties on both sides during the Battle of Kursk, due to erratic and incomplete record keeping on the German sides and the secrecy of the Russians.

Soviet casulties totaled 863,000 killed, wounded, and captured. The Russians lost 6,060 tanks and self-propelled guns, 5,200 guns and mortars, and over 1,600 combat aircraft. German casualties came to 110,000 killed, wounded, and missing. The Germans lost 1,600 tanks and self-propelled guns and 840 combat aircraft.

“Citadel was a complete and most regrettable failure,” stated General Friedrich von Mellenthin, Chief of Staff of the XLVIII Panzer Corps, in his account of the war. “It is true that Russian losses were much heavier than German; indeed, tactically the fighting had been indecisive…. But our panzer divisions, which were in such splendid shape at the beginning of the battle, had been bled white, and with Anglo-American assistance the Russians could afford losses on this colossal scale.”

Von Manstein noted that the German defeat at Kursk put the Germans on the defensive for the remainder of the war. “When Citadel was called off, the initiative in the Eastern Theater of war finally passed to the Russians,” Von Manstein wrote in his memoirs. “To maintain ourselves in the field, and in doing so to wear down the enemy’s offensive capability to the utmost, became the whole essence of this struggle.”

Zhukov concurred with Manstein’s assessment. “The specter of imminent catastrophe faced Fascist Germany,” he wrote. “The defeat of the German troops forced [Hitler’s generals] to transfer 14 divisions and significant reinforcements from other fronts to the Soviet-German front in the summer of 1943, thereby weakening their fronts in Italy and France…. Hitler’ attempt to wrestle strategic initiative from the hand of the Soviet command ended in compete failure, and from then until the end of the war, German troops were forced to conduct only defensive battles.”

The Battle of Kursk had far-reaching consequences. First and foremost, the strategic initiative shifted irreversibly to the Soviet Union. In the follow-on offensives, the Red Army liberated the left bank of the Ukraine and retook the Ukrainian capital of Kiev. A couplet from a Russian war song underscores the significance of the Soviet victory at Kursk: “From Orel and Kursk, the war took us to the very gates of the enemy.”