By Matthew R. Lamothe

Tired, hungry, and typhoid-ridden, the French veterans in the Grand Army of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte staggered through the Fulda Gap in central Germany on October 27, 1813. They and their emperor had suffered a crushing defeat eight days earlier in Saxony at the titanic Battle of Leipzig at the hands of the Allied powers of Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Sweden. Napoleon had reacted to the unaccustomed defeat by withdrawing southwest to the French-held city of Erfurt, which he reached on October 23. While his ever-resolute rear guard kept them at bay, Napoleon intended to counterattack the pursuing Austrian and Prussian armies. He still had 70,000 men under arms and felt that this was more than sufficient to deal the Allies a painful blow.

The Allied victory at Leipzig had loosened Napoleon’s political control over the Confederation of the Rhine, causing some German member states to break their allegiance to France. It was evident to Napoleon that with each German defection he was in greater danger of encirclement. While in Erfurt the emperor learned that Bavaria, one of the most important former members of the Confederation, was raising an army intent on cutting him off from France. Realizing that he had no other choice, Napoleon gave the order to continue the retreat west toward the Fulda Gap. Despite the typically dreary autumn weather, marauding Russian Cossacks, and constant Prussian pressure on his rear, Napoleon still managed to guide his army through Gotha and Eisenach before finally establishing his imperial headquarters in the village of Hünfeld, just north of Fulda.

Even though victorious, the Allied soldiers pursuing Napoleon were not supermen, and they suffered the same privations that were plaguing their French enemy. The exhausted French soldiers had maintained a marching pace of 20 miles a day, gradually outdistancing the Austrians and Prussians, who maintained a pace just under 19 miles a day. A Prussian cavalry raid conducted on imperial headquarters on October 27 was the last gasp of the Allied pursuit. Not wishing to allow the Allies to catch up, Napoleon issued orders to continue the retreat along a southwesterly route through the Kinzig Valley, eventually ending at Mainz, a vital crossing point on the Rhine River. Once the Rhine was crossed, Napoleon intended to reform the Grand Army on the relative security of French soil.

Napoleon’s chosen path followed a road along the Kinzig River, which formed the valley bearing the same name. The Grand Army had to pass through the towns of Schlüchtern and Salmünster before reaching a strategic defile located at Gelnhausen. The defile would act as a bottleneck if the Bavarian Army could occupy it before the French Vanguard arrived. Then, if the Bavarians could hold the defile and delay the French long enough, perhaps the Austrian Army of Bohemia could catch up and encircle the French. Otherwise, if Napoleon successfully passed through the Gelnhausen defile, his army could march through the town of Langensebold, eventually arriving at the Lamboy forest. After having gone through the Lamboy forest, the army would follow the road located just north of the French-held town of Hanau and exit the Kinzig Valley. From Hanau, the French would follow the Main River through the city of Frankfurt before reaching Mainz, with France lying tantalizingly on the opposite bank of the Rhine.

While their own troops caught their breath, the Allied commanders were planning their next moves. They realized that Napoleon had two options for reaching France from the Fulda Gap. Either the French would follow a northerly route from Fulda through Wetzlar, eventually reaching the Rhine crossing at Koblenz, or else Napoleon would follow the southerly route through the Kinzig Valley to Mainz. Unbeknownst to the Allies, the emperor had already chosen the second option.

The Prussian Army of Silesia, commanded by 77-year-old Marshal Gebhard von Blücher, was located just north of the French Army between Hünfeld and Bad Hersfeld. Blücher, a determined but tactically challenged commander, predicted that Napoleon would follow the northern route and cross the Rhine at Koblenz. The Prussian marshal also believed that Napoleon would send his sick and wounded soldiers, camp followers, and baggage on the southern route through the Kinzig Valley to Mainz. The commander of the Austrian Army of Bohemia, Field Marshal Karl zu Schwarzenberg, agreed with Blücher’s predictions. As Blücher went chasing French phantoms along the northern route in hopes of attacking Napoleon’s right flank, Schwarzenberg alerted Bavarian General Karl Philipp von Wrede, commander of the Austro-Bavarian Army that was besieging the occupied city of Würzburg on the Main River, of the possible approach of a weak French column north of his location. Wrede’s command was the closest Allied force to the French southern avenue of retreat.

Wrede, an energetic, ambitious officer who possessed a commanding presence, had served in Bavaria’s army in support of Napoleon’s campaigns in Austria and Russia. Despite having been made a Count of the Empire by Napoleon, Wrede felt that he had never gotten due respect from Napoleon’s marshals and developed accordingly into a solidly anti-French politician at the Bavarian royal court in Munich. Prior to the Battle of Leipzig, Wrede had been entrusted by Bavarian King Maximilian I to negotiate a truce with Austria. Under the resulting Treaty of Ried, Wrede created a three-division Bavarian army, which was ordered to march from southern Bavaria to the Main River, placing it in the rear of Napoleon’s army in Saxony. Wrede’s army was reinforced by an Austrian corps under the leadership of Lieutenant Field Marshal Count Fresnel, who placed his men under the Bavarian general’s command as mandated by the recent treaty.

Wrede marched his combined army north, eventually laying siege to the city of Würzburg on October 24. Within two days Wrede had taken most of the city, forcing the 3,000-man French contingent to seek refuge in the nearby Marienberg fortress. While Wrede’s men secured the city, irregular reinforcements appeared in the Allied camp, namely the Mensdorf Streifkorps, consisting of Russian Cossacks commanded by General Alexander Tshernishev, a Prussian cavalry squadron from the Neumark Dragoon Regiment, and three squadrons of Austrian hussars.

When Wrede received Schwarzenberg’s warning predicting that a disorganized French column, not numbering over 20,000 men, would pass near his location via the Kinzig Valley, the Bavarian general sprang into action. Wrede saw a vulnerable target coming his way and wanted to destroy it—there was no more glory to be had in Würzburg. Wrede planned to set up a cavalry screen between Salmünster and Gelnhausen, which would warn him of the French column’s approach. Another force would be sent to Frankfurt to occupy the crossings over the Main River. Meanwhile, he would take the bulk of his army to Hanau and lie in wait in the Lamboy forest, ambushing the French as they passed through his position.

Wrede dispatched Austrian Maj. Gen. von Volkmann to the Gelnhausen-Salmünster area in the Kinzig Valley to throw up roadblocks across the main road. Volkmann’s command consisted of the 3rd Jäger Battalion and the 2nd Schwarzenberg Uhlan Regiment. Wrede won the race to Gelnhausen when Volkmann occupied the defile, but the Bavarian commander didn’t seem to realize its significance as a bottleneck. Wrede was more concerned with laying his trap in the Lamboy forest.

Leaving a large enough force to keep an eye on the Marienberg fortress, Wrede took the bulk of his army northwest along the Main River to the city of Aschaffenburg, just to the southeast of Hanau. The march to Aschaffenburg was rapid, causing some weary Bavarian soldiers to fall out. After establishing his camp at Aschaffenburg, Wrede ordered Lt. Gen. Count Rechberg to take his Bavarian 1st Division, numbering approximately 10,000 men, to occupy Frankfurt. The next day, Wrede would occupy Hanau with the rest of his army, numbering 33,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 100 cannon. In their haste to leave Würzburg, Wrede’s staff had committed a grave error. The officer in charge of the artillery ammunition reserve was not informed of the march to Aschaffenburg and remained at Würzburg, depriving Wrede’s artillery of badly needed ammunition.

Hanau, a walled town of 15,000 citizens belonging to the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt, was located at the confluence of the Kinzig and Main Rivers, 29 miles from Mainz. The now-swollen Kinzig River formed the northern and western borders of Hanau. The river could be crossed by two vital bridges—the Kinzig bridge located at the northwest corner of Hanau, and the Lamboy bridge in the middle of a soggy plain located between the town and the Lamboy forest. Just north of the Lamboy bridge was a cluster of farmhouses called the Neuhof; to the south of the bridge was another cluster called the Lehrhof. The Main River flowed just south of Hanau before emptying into the Rhine at Mainz. To the northeast of the town was a hill that commanded the plain leading to the forest. The plain itself, approximately half a mile wide, was bordered to the north by the Puppen forest, to the east by the Lamboy forest, and to the southeast by the Bülau forest. The Lamboy forest was passable by the main road from Gelnhausen and by many woodcutters’ tracks that crisscrossed the woods. The main road exited the forest and passed just north of Hanau without actually entering the town itself. Hanau was a busy traffic hub, linking Frankfurt to the roads from Fulda, Friedberg to the north, and Aschaffenburg to the southeast.

The French garrison in Hanau, consisting of a hussar regiment and an artillery battery, had become demoralized as wounded French soldiers passed through town and spread the word about the defeat at Leipzig. The waterlogged fortifications were in a state of disrepair. It was questionable if the garrison would put up much of a fight.

On the morning of October 28, the French vanguard galloped through the town of Schlüchtern on its way to Austrian-held Salmünster. Riding point for the French was the 4th Light Cavalry Division, commanded by General Rémy Exelmans, part of Corsican General Horace Sébastiani’s II Cavalry Corps. Sébastiani was ironically nicknamed “General Surprise” by some of his cavalry troopers due to his perceived lack of tactical skill. On this day, however, General Surprise demonstrated some real tactical know-how as his cavalry pushed through the roadblock at Salmünster and continued on to Gelnhausen.

Upon reaching Gelnhausen, Sébastiani’s cavalry was confronted by Austrian hussars and uhlans supported by the 3rd Jäger Battalion. Realizing that he was at a tactical disadvantage due to a lack of infantry support, Sébastiani ordered the commander of the 23rd Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment, the famed Colonel Marcellin Marbot, to dismount his troopers and attack on foot with their carbines. In short order the Austrian cavalry was chased from the area, while Marbot forced the Austrian light infantry out of Gelnhausen.

Meanwhile, at 7 am, Wrede sent the Bavarian 1st Chevau-Legers Regiment to attack and occupy Hanau. When the Bavarian light horsemen, distinguishable by their tall, crested headgear called raupenhelme, arrived outside Hanau, the French garrison evacuated the town via the Kinzig bridge and marched north along the Friedberg road. The Bavarian riders entered Hanau through the Nuremburg gate along the south wall to the delighted cheers of the townsfolk. The Bavarians didn’t waste time greeting the locals, but galloped after the retreating French garrison, skirmishing with them along the Friedberg road. The Bavarian victory was short-lived, however, as French cavalry reinforcements arrived in the afternoon and retook the town. The Lamboy bridge was the site of further skirmishings during which the nephew of Bavarian Crown Prince Ludwig was mortally wounded, dying later that night.

While reports filtered into the Bavarian camp that Hanau was back in French hands, Austrian Colonel Scheibler of the 2nd Squadron, 11th Székler Hussars, reported that the French Army was moving through Gelnhausen in force. Scheibler’s report was confirmed by the Cossacks, who claimed that they had spotted Napoleon and the Imperial Guard marching toward Gelnhausen. Ignoring the intelligence reports, Wrede remained undeterred and ordered the entire 1st Light Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Maj. Gen. von Vieregg, to retake Hanau. Once Vieregg had accomplished his mission, he was then to head toward Gelnhausen and halt Sébastiani’s advance, which Wrede still thought represented little more than a disorganized rabble.

Vieregg’s light cavalry attacked and recaptured Hanau, but increasing numbers of French forces in the area prevented him from moving to Gelnhausen. By 8 pm, the Bavarians were forced to abandon Hanau for a second time. Wrede persistently ordered the commander of the Bavarian 3rd Division, Lt. Gen. de Lamotte, to recapture Hanau. Spearheaded by four light infantry companies, Lamotte assaulted and captured Hanau by 10 pm. Aware of the increasing French presence in the area, Lamotte ordered Maj. Gen. von Deroy’s 2nd Brigade to clear any remaining enemy forces from around Hanau and then deploy across the Gelnhausen road. The rest of the night passed quietly.

The remainder of the Austro-Bavarian Army began moving into Hanau on the morning of October 29. At 8 am, a mixed French force of infantry and cavalry attacked and tried to regain control of Hanau. The French were easily repulsed, the Bavarians netting two artillery pieces in the process. The two days of skirmishing resulted in the capture of nearly 5,000 French prisoners of war by the Allies. At 2 pm, a confident Wrede entered Hanau, still believing he was about to pounce on a disorganized French column. The Bavarian commander began deploying his units on a two-mile front facing the Lamboy forest.

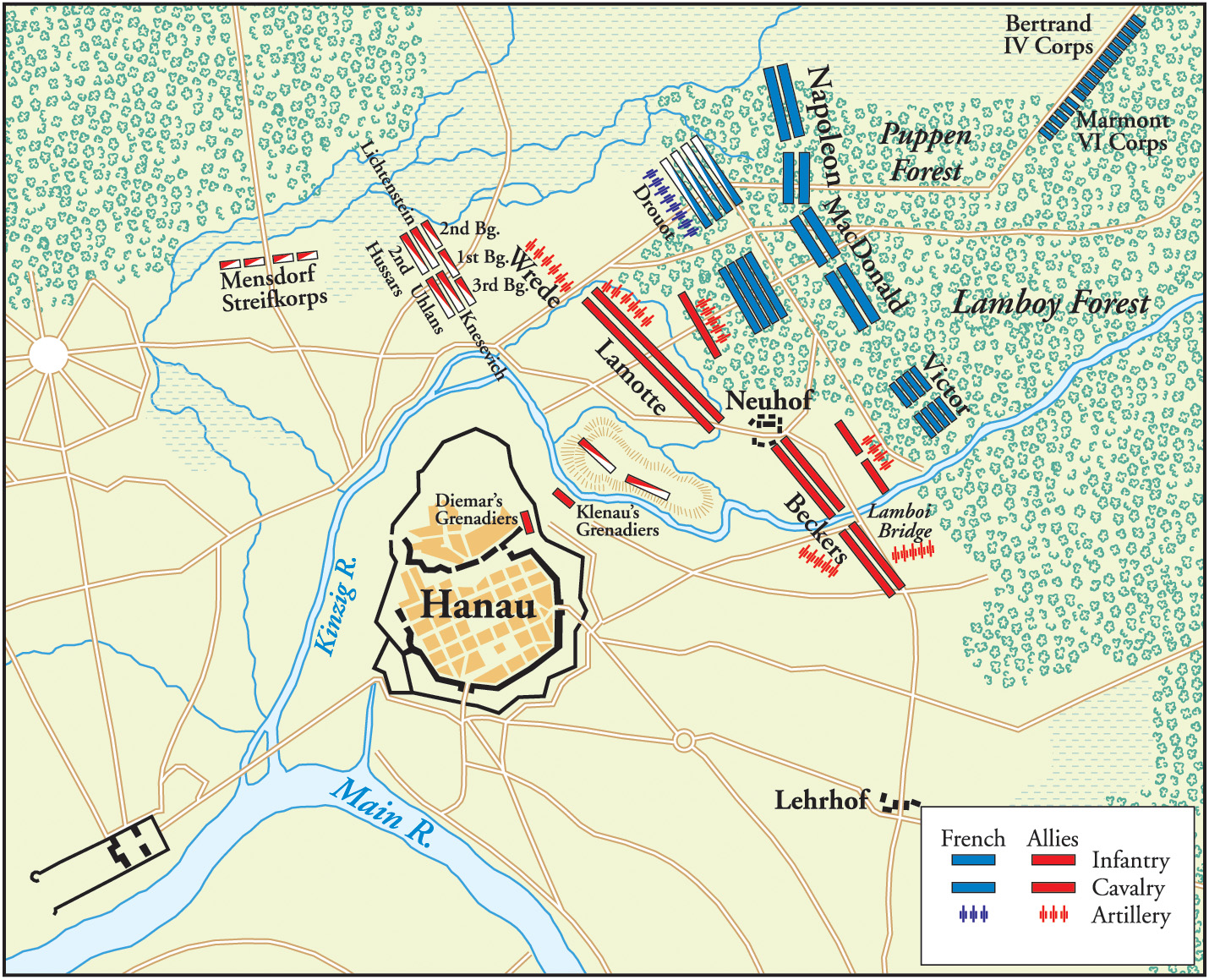

On his extreme left, protecting the Friedberg road, Wrede deployed the Austrian 3rd Jäger Battalion, supported by the Mensdorf Streifkorps. The left flank proper was formed by three lines of cavalry deployed roughly from the Friedberg road to the other side of the Gelnhausen road. A battery of 28 guns, supported by the Austrian 14th Archduke Rudolf Infantry Regiment, was deployed forward of the cavalry. In the first line of cavalry, from left to right, was the 2nd Light Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Maj. Gen. von Elbracht, Vieregg’s 1st Light Cavalry Brigade, and the 3rd Light Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Colonel Diez. The second line was formed by the Austrian Liechtenstein Cuirassier Regiment and the 3rd Knesevich Dragoon Regiment. The third line was manned by the Austrian 2nd Archduke Joseph Hussar Regiment and the 2nd Schwarzenberg Uhlan Regiment, which had arrived in the Hanau area at about 6 pm that evening when Volkmann rejoined the main body of the Austro-Bavarian Army.

Lamotte’s Bavarian 3rd Division formed the center, located on the plain between the left and right flanks. Lamotte deployed his command in two lines anchored by the Neuhof. Deployed forward was the 1st Brigade, commanded by Maj. Gen. Jason von der Stockh. Deroy’s 2nd Brigade manned the rear line. The center’s right wing was covered by the Székler Border Hussars. Lamotte ordered his subordinate commanders to deploy their light infantry companies in a skirmish line on the Gelnhausen side of the Lamboy forest. The hill overlooking the plain provided Lamotte with the ideal spot to deploy two artillery batteries. Wrede kept Austrian Maj. Gen. Johann Klenau’s Grenadier Brigade in reserve on the left bank of the Kinzig just behind the hill containing Lamotte’s batteries. Austrian Maj. Gen. von Diemar’s Grenadier Brigade acted as Hanau’s garrison.

Wrede’s right flank, anchored by the Lehrhof, was the responsibility of Lt. Gen. von Beckers’ Bavarian 2nd Division, which was located on both banks of the Kinzig River covering the Lamboy bridge. Beckers sent the Austrian 1st Székler Border Infantry Regiment to the outer edge of the Lamboy forest as skirmishers, while placing the Austrian 59th Jordis Infantry Regiment behind his forward deployed Bavarian troops. The right flank remained undermanned until the start of the battle since many of Beckers’ units were still en route from Aschaffenburg.

Wrede’s battle line was fraught with errors. On his left flank, the cavalry was deployed out in the open, leaving it vulnerable to artillery bombardment. His center was dangerously deployed with the Kinzig River to its rear, a problem in case Lamotte needed to fall back. Beckers would have a hard time holding the right flank because the Kinzig actually flowed through the center of his position. Either Wrede didn’t have the tactical knowledge to see the errors of his deployment, or he was simply overconfident that he could defeat any French force coming down the Gelnhausen road.

While Wrede was deploying his men for battle, Napoleon had set up the imperial headquarters in Isenberg Castle near Gelnhausen. The emperor spent the day awaiting intelligence reports regarding the enemy’s dispositions. His army was strung out from Gelnhausen back to the Fulda Gap, while the Austrians were still trying to catch up to him. Headquarters, as usual, was protected by the infantry of the Guard, commanded by General Louis Friant. Line infantry support under the emperor’s direct command was provided by the II Corps, commanded by Marshal Claude Victor, and the remnants of the XI and V Corps, commanded by Marshal Jacques Macdonald. Both of these corps had suffered terribly during the Battle of Leipzig. Still to arrive was the VI Corps, commanded by Marshal Auguste Marmont, and the IV Corps, commanded by General Henri Bertrand. Napoleon was irritated with Marmont due to his continued absence, causing the emperor to complain that his orders were no longer followed. On hand for cavalry support, Napoleon had the Imperial Guard Cavalry, commanded by General Etienne Nansouty, Sébastiani’s II Cavalry Corps, and the III Cavalry Corps, commanded by the emperor’s nephew, Jean Arrighi de Casanova.

Sébastiani’s II Cavalry Corps and the 2nd Guard Cavalry Division, commanded by General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes, had spent the day scouting between Gelnhausen and the Lamboy forest to gather intelligence on the availability of the route to Mainz. As the sun set, Lefebvre-Desnouettes arrived at Isenberg Castle to report to the emperor that needed bridges were guarded or destroyed, the roads to Mainz were cut, and that Wrede occupied the Lamboy forest in force, essentially blocking the way to the Rhine. This information was confirmed via the interrogation of recently captured Bavarian soldiers.

Sleep did not come easy at Isenberg Castle as Napoleon and his staff prepared throughout the night for the next day’s battle. Napoleon believed he could push through Wrede’s roadblock with the forces on hand and then continue on to Frankfurt. The emperor ordered Arrighi to escort the noncombatants and non-essential equipment north to Koblenz to increase French mobility.

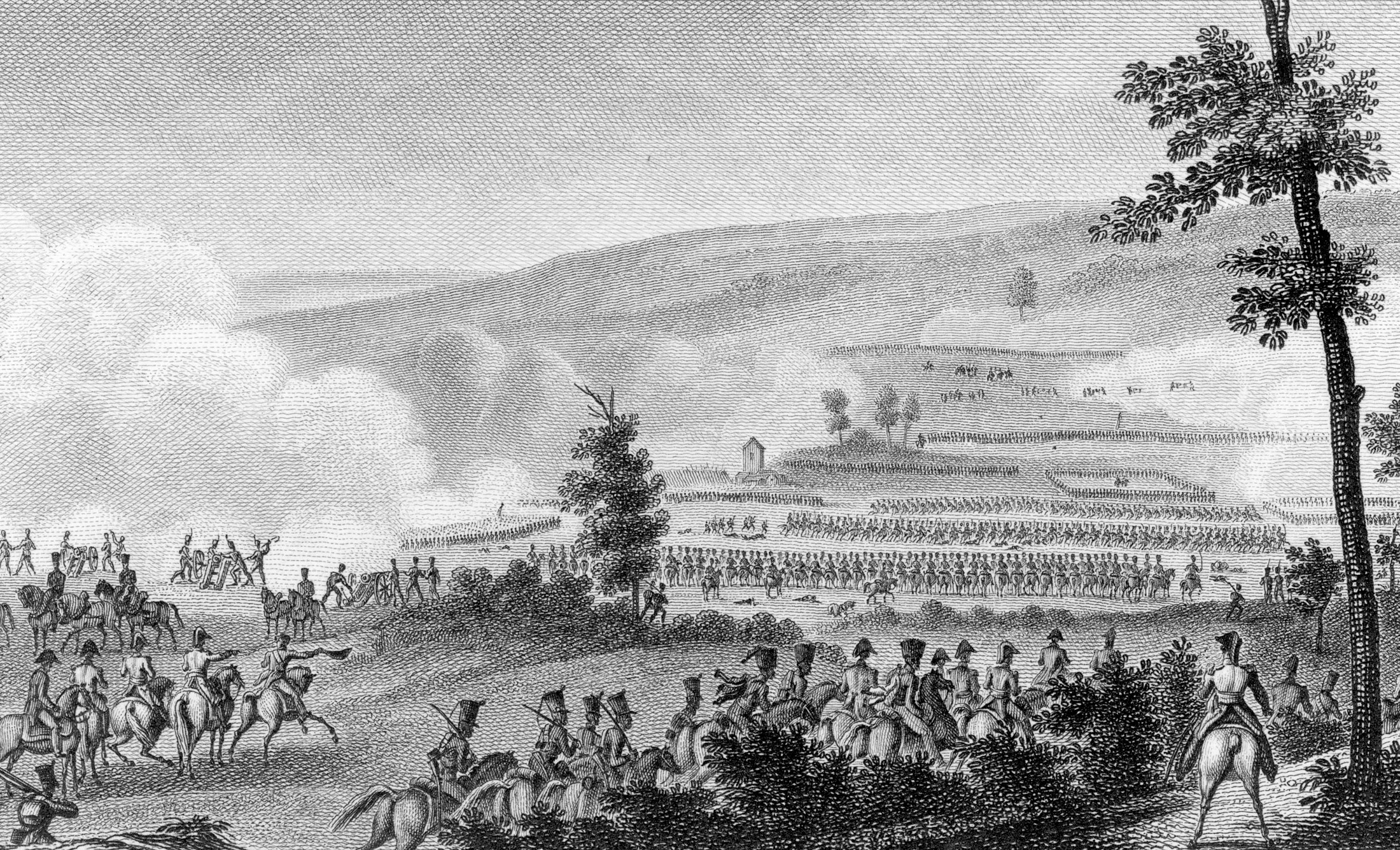

As sleet fell during the early morning hours of October 30, the Grand Army formed for battle on the Gelnhausen road along a mile-wide front facing the Lamboy forest. Victor’s II Corps was deployed on the left flank along the Kinzig River. Napoleon was located in the center with the Imperial Guard and what was left of XI and V Corps. The right flank was covered by Lefebvre-Desnouettes’ 2nd Guard Cavalry Division. Macdonald and Victor were the first to move out, while the emperor formed the Imperial Guard near Langensebold.

The Battle of Hanau commenced at around 8 am when 3,000 skirmishers belonging to General Henri Charpentier’s 36th Division of XI Corps engaged Lamotte’s skirmish line on the outer edge of the Lamboy forest, driving the light infantry company of the 3rd Prinz Karl Infantry Regiment into the wood line. A unit from the Székler Border Hussars and a squadron from the 2nd Chevau-Legers Regiment galloped forward in support of the Bavarian light infantry, but they were intercepted by 2,000 French cavalry troopers, accompanied by two artillery pieces, of Sébastiani’s II Cavalry Corps. As the pair of French guns fired into the Austrian and Bavarian skirmishers, another 2,000 French infantry belonging to General Jean Dubreton’s 4th Division of II Corps arrived on the scene with Victor at their head.

The pressure was too much for Lamotte’s skirmishers, and they soon fell back through the Lamboy forest, allowing Sébastiani to move his cavalry forward along the woodcutters’ tracks. Upon reaching the inner edge of the forest, Sébastiani ordered the carabiniers and cuirassiers of General Claude de St. Germain’s 2nd Heavy Cavalry Division to charge across the plain and attack the main Austro-Bavarian line. As the armored troopers broke out of the wood line, the alert Bavarians opened fire. With musket balls clanging into the French cuirasses, St. Germain gave the order to fall back into the Lamboy forest. At 10 am, Deroy followed up on the repulse of the French heavy cavalry and ordered the 8th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Hausmann, to counterattack into the forest. Hausmann’s Bavarian line infantry pushed Macdonald’s men back out of the woods and reestablished the original Austro-Bavarian skirmish line on the Lamboy forest’s outer edge. Round one had gone to Wrede.

At around noon, Macdonald’s and Victor’s remaining formations, approximately 6,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and six guns, finally arrived via the Gelnhausen road. Both marshals attacked the Bavarian skirmish line again. On Wrede’s right flank, the Austrian Székler Border Infantry Regiment ran out of ammunition and was forced to fall back through the forest to Beckers’ main line. Victor’s II Corps followed closely, occupying the Lamboy forest opposite the Austro-Bavarian right flank. Victor tried to maintain the momentum of his success and ordered his men to attack the enemy right flank. Beckers’ artillery opened fire, forcing the Frenchmen back into the inner wood line. Macdonald was able to force his way back into the woods as well, but was also unable to break out of the Lamboy forest due to heavy Bavarian artillery fire. The battle developed into a stalemate, with Charpentier’s artillery trading shots with Lamotte’s guns while Dubreton’s cannon dueled with those belonging to Beckers. A large number of Bavarian skirmishers belonging to von der Stockh’s 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, were still holding out in the woods on the Allied left flank, denying the French full control of the Lamboy forest.

Wrede prepared his men for the next phase of the battle as he saw it developing. At 1 pm, he issued a confident, even cocky order, “As reported, only part of the Grande Armée stands before us. The [advanced] brigades shall steadfastly repel further assaults by the French to permit us to maneuver around the French corps facing us and capture it lock, stock, and barrel.”

Later in the afternoon, Napoleon and the Guard were approaching the Lamboy forest, having already heard the battle from a distance. As the emperor entered the woods, Bavarian cannonballs were crashing through the trees all around him, showering the Guard with branches and wood splinters. The commander of the Guard Artillery, General Count Antoine Drouot, implored Napoleon to leave the forest and seek safety. Napoleon brushed aside Drouot’s concerns, stating that he needed to “see for myself the enemy dispositions.” Upon observing Wrede’s battle line, Napoleon indeed realized that the Bavarian general was blocking his way to Mainz. Napoleon’s trained eye also understood the folly of Wrede’s position with the Kinzig River flowing through and behind the Bavarian infantry divisions and with the Allied cavalry deployed in the open. Napoleon clucked, “Poor Wrede, I made him a count, but I could never make him a general.” The emperor was confident that with the 17,000 men he had available, and with a further 13,000 still coming down the road, he could punch his way through Wrede’s roadblock.

The raucous cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” emanating from the Lamboy forest were not lost on the Austrian and Bavarian soldiers. A staff officer entered Wrede’s headquarters and reported the presence of Napoleon on the battlefield. Wrede’s illusions of destroying a disorganized rabble were dashed. He was on his own, with the nearest Allied unit still 24 miles away. The Bavarian general lost his usual confidence, remarking; “Now there is nothing else to do. We must fight as best we can like brave soldiers.” Wrede ordered Beckers to transfer a brigade over to Lamotte to strengthen the Austro-Bavarian center in anticipation of Napoleon’s first attack.

Napoleon observed Wrede reinforcing his center and decided to hammer the unprotected enemy cavalry on the left flank. Once Wrede’s cavalry was destroyed, Napoleon could attack toward the Lamboy bridge and split Wrede’s line in two. While a rear guard kept Wrede pinned to the Kinzig, Napoleon would take the rest of the army to Frankfurt via the then open road north of Hanau. The Bavarian skirmishers still holding out on his right flank were preventing the emperor from making full use of the Lamboy forest. He decided to deal with these nettlesome Bavarians first.

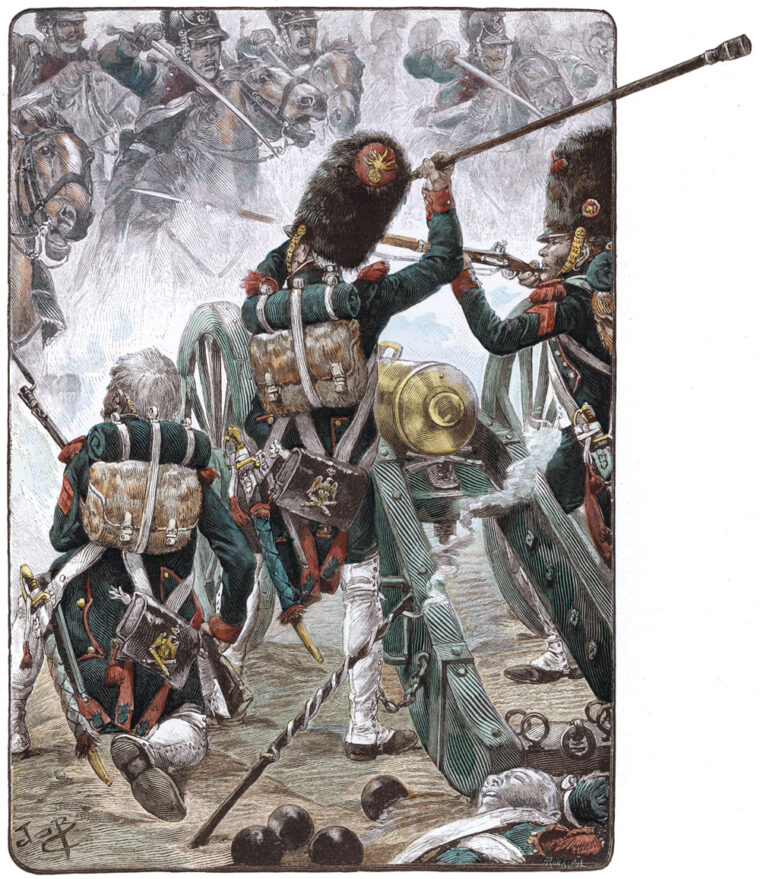

For this task, Napoleon turned to General Philibert Curial, commander of the Old Guard Chasseurs à Pied Brigade, and ordered, “The Chasseurs will charge.” Curial in turn ordered General Pierre Cambronne to clear the enemy skirmishers out of the Lamboy forest with his 2nd Chasseurs à Pied Regiment. At around 3 pm, the tough French general ordered his veteran soldiers to leave their muskets plugged—this was to be a bayonet charge. The Bavarian skirmishers opened fire as the bearskin bonnets methodically moved through the trees. General Cambronne and 12 other officers fell wounded, but their men continued on without them, contemptuously kicking the Bavarians out of the forest on the points of their bayonets. General Lubin Griois of the Guard Artillery remarked, “One is proud to wear the uniform when he sees soldiers like these.” Napoleon now had full control of the forest.

While the chasseurs were clearing the forest of the enemy, Drouot had been conducting a personal reconnaissance of the woodcutters’ tracks. He found suitable paths to move the Guard Artillery up to the inner edge of the forest, from which position he could open fire on Wrede’s line. Drouot assured the emperor, “I promise to force a passage with 50 cannon.” Napoleon gave Drouot permission to deploy his artillery as he saw fit. The Guard Foot and Horse Artillery began moving their pieces through the woods. The problem with Drouot’s plan was that if attacked by cavalry, he would be unable to pull his guns back into the forest quickly enough. Napoleon ordered Nansouty and Sébastiani to form their cavalry by troop on the Gelnhausen road and prepare to charge across the plain toward the enemy center and left flank. Meanwhile, Lefebvre-Desnouettes was ordered to take his cavalry division over to the Friedberg road area and ensure that the Mensdorf Streifkorps didn’t attempt to turn the French right flank. The Old Guard infantry was held in reserve as usual.

Drouot’s guns deployed one by one out of the tree line and opened fire on the Allied lines. The bombardment increased as each gun was manhandled into position. It wasn’t long before the veteran gun crews of the Guard Artillery knocked out 28 of Wrede’s cannon. Wrede’s crews were not able to sustain continued counterbattery fire since their ammunition reserve was still in Würzburg. Wrede had no choice but to pull his guns out of French artillery range or risk losing them.

Wrede ordered the cavalry on the left flank to charge Drouot’s battery and mask the withdrawal of the artillery. The Austro-Bavarian cavalry, 7,000 strong on a front, advanced over the soggy ground toward the French battery. Drouot’s gun crews remained calm at their pieces as the Bavarian light horse trotted closer, and then galloped to contact. When the Bavarians got to within 65 yards, Drouot gave the order to fire. The front ranks of the Allied cavalry were torn apart by the point-blank fire, knocking down both horses and riders as Bavarian Raupenhelme flew through the air. Nevertheless, the Bavarian light horse closed ranks and crashed into the French battery. Drouot rallied his gun crews while engaging in a fight with a Bavarian officer.

The smoke from the cannonfire concealed the advance of General Claude Guyot’s Guard Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment, which galloped from the forest to the aid of its artillery comrades. As the Bavarian light horsemen were engaged by the elite of the Guard cavalry, Nansouty and Sébastiani had formed three ranks to the right of Drouot’s battery. Nansouty gave the order to charge, sending forward the Empress Dragoons, under General Louis Letort; the Grenadiers à Cheval, nicknamed “the Gods,” commanded by General Laferriere Lavêque; the Polish Lancers, commanded by Colonel Dautancourt; and St. Germain’s 2nd Heavy Cavalry Division. The already bloodied Bavarian troopers were cut to pieces by this fresh assault. Nansouty, impressed by the way the Polish Lancers had sliced through the enemy, called to Dautancourt that he “might consider himself promoted to Major General.” The Allied cavalry retreated back to their own lines and rallied on the Friedberg Road while covered by the Mensdorf Streifkorps.

Seeing the approach of the French Guard Cavalry, the Bavarian and Austrian infantry had formed into squares. Drouot, meanwhile, put his gun crews back to work and advanced his battery 440 yards toward the Allied infantry, opening fire with canister and tearing huge holes in the enemy squares. As Drouot’s grapeshot weakened the Allied squares, Nansouty and Sébastiani reformed and turned their attention to Wrede’s center. The French cavalry charged through the Austrian 14th Infantry Regiment and slammed into the Bavarian 5th and 8th Infantry Regiments of Deroy’s brigade. Letort’s Dragoons overran three Bavarian squares, while Guyot’s Chasseurs à Cheval captured two Bavarian battalions. To make matters worse, General von der Stockh was killed, leaving Lamotte’s 1st Brigade leaderless. The center broke under the onslaught and the Bavarian infantry began crowding toward the Lamboy bridge. Many Austrian and Bavarian soldiers drowned in the Kinzig River while trying to reach safety. Wrede’s appeals to Beckers to aid Lamotte were fruitless—the Bavarian right could not maneuver through the retreating center.

Meanwhile, the Bavarian cavalry had reformed and launched itself at Drouot’s battery once more, drawing the French cavalry away from the Allied infantry and to the aid of the Guard Artillery. The battle was sapping the strength of the French cavalry—the engagement around Drouot’s battery hung in the balance. Napoleon ordered the yet untested Guards of Honor to charge to the aid of their comrades. The Guards of Honor were viewed with suspicion by the senior regiments of the Guard since their members came from the rich upper class. Many felt that their creation was a ploy by Napoleon to bind the nobility to his side during a time of crisis for his empire. Despite having already exhausted their horses, 400 troopers of the 3rd Guards of Honor led by Col. Gen. de Saluces entered the fray as the Grenadiers à Cheval were being forced backward. Saluces’ troopers crashed into the Bavarian horsemen, relieving the Gods and allowing them to reform and reenter the fight. Out of appreciation, the Gods cheered the 3rd Guards of Honor with the cry, “Vive les Gardes d’Honneur!” Napoleon commended Saluces and his men for their bravery, later awarding many of the 3rd Regiment troopers with the Legion of Honor.

With his artillery ammunition dangerously low and his left flank and center in a shambles, Wrede prepared to retreat behind the Kinzig River at about 5 pm. Before he could pull back, however, Wrede needed to throw the French temporarily off balance. He ordered Beckers to launch an attack on Victor’s and Macdonald’s corps. Beckers complied and drove the French left flank back into the Lamboy forest. Napoleon who was indeed distracted by Beckers’ assault, was compelled to order Friant to bring the situation on the left flank back under control. Friant sent General Claude Michel’s Old Guard Grenadier Brigade to attack the advancing Bavarians. The feared “Grognards” of the Old Guard swept Beckers’ 2nd Division from the field, capturing the Neuhof and securing the road to Frankfurt in the process.

At 6 pm, in failing daylight, Wrede signaled the retreat, ordering his cavalry to screen the rearward movement of the army. The center and right flank scrambled over the Lamboy bridge and reached the safety of the left bank of the Kinzig. What remained of the left flank retreated to Hanau with the Guard Cavalry in pursuit. Fearing the collapse of the Austro-Bavarian Army, Tshernishev led the Cossacks away from the battlefield despite Wrede’s pleas to remain.

At 7 pm, Wrede rallied his shattered battalions around the Lehrhof. His right flank was placed opposite the Lamboy bridge, while his center rallied along the Aschaffenburg road. His left flank maintained control of Hanau. For his part, Napoleon probably felt that he had thrashed a disloyal ally long enough and did not wish to continue the fight. Exelmans’ 4th Light Cavalry Division was ordered to scout ahead toward Frankfurt, while Lefebvre-Desnouettes went to clear the Friedberg road of any remaining Russian Cossacks that might still be lurking to the north. As the vanguard moved out, the rest of the French Army bivouacked in the Lamboy forest in a cold rain that prevented the lighting of any campfires.

Later that night, Marmont finally arrived on the battlefield. Napoleon ordered him to capture and occupy Hanau, thus preventing Wrede from attacking the Grand Army as it left the battlefield. Marmont was to be relieved by the IV Corps when Bertrand eventually arrived. At 2 am on October 31, Marmont opened up an artillery bombardment on Hanau, setting part of the town on fire. He then sent General Jean Charriere’s 2nd Brigade, formerly of the 8th Division, III Corps (which was lost at Leipzig), to storm the town. After Diemar’s Austrian Grenadier Brigade repulsed Charriere’s men, Marmont decided to allow his artillery to pummel the town a while longer before ordering another assault. As the fires in Hanau spread, Wrede pulled Diemar’s grenadiers out of town via the Nuremburg gate, rallying them at the Lehrhof. Charriere’s hungry soldiers entered Hanau after the Austrians completed their evacuation and broke into people’s homes looking for food.

At dawn a group of town officials parleyed with Napoleon, begging the emperor to spare Hanau any further destruction. After the meeting ended, Napoleon gave the order to march on Frankfurt, taking much of the army with him. At 11 am, Exelmans’ light cavalry division entered the Frankfurt suburb of Sachsenhausen, announcing the approach of the emperor. Instead of contesting Frankfurt, General Rechberg evacuated the city, not wishing to engage Napoleon by himself.

As the French main body moved out, Bertrand’s IV Corps was arriving in the Hanau area. Deciding that he needed to buy time for Bertrand to fully deploy, Marmont ordered an assault to gain control of the Lamboy bridge on his left flank, while at the same time pushing Wrede’s troops back from Hanau’s walls. Marmont’s soldiers spilled out of the Aschaffenburg and Steinheim gates on Hanau’s south wall, driving the Allies to the very banks of the Main River. Wrede rallied his men and turned the tide, pushing the French back into Hanau. On Marmont’s left flank, the Austrian 14th and 59th Infantry Regiments forced the French back over the Lamboy bridge. Marmont made sure his men fell back slowly, buying time for Bertrand to take responsibility for Hanau.

Marmont’s tactics worked, allowing Bertrand to take over by noon. Bertrand ordered General Armand Guilleminot’s 13th Division, backed up by a 12-gun battery, to guard the Lamboy bridge, which was in poor shape, having caught fire the night before. Bertrand deployed General Fontanelli’s Italian 15th Division in Hanau’s suburbs, securing the right flank. General Charles Morand’s 12th Division was placed in reserve to the northwest of Hanau, covering the Kinzig bridge.

As for Wrede, his artillery was almost out of ammunition, with only two Bavarian and one Austrian battery fit for battle. His cavalry too was in sad shape, having lost 47 officers, 869 troopers, and 979 horses. But after realizing that he was facing a single, weak corps, Wrede decided to attack again. The ambitious general planned a two-pronged assault, one prong attacking Hanau, the other the Lamboy bridge. Wrede would lead the assault on Hanau himself at the head of Diemar’s Austrian Grenadier Brigade, the 3rd Jägers, the 14th Infantry Regiment, and the Székler Border Hussars. Lieutenant Field Marshal Fresnel would lead Beckers’ 2nd Division, plus two additional regiments, in the attack on the Lamboy bridge. Once Fresnel took the bridge, the cavalry would gallop across the Kinzig and strike the rear of the French column.

At 3 pm, Wrede ordered his artillery to open fire as Fresnel led the attack on the Lamboy bridge. The Bavarians forced their way onto the bridge, which bent under their weight. Guilleminot’s 13th Division would not break, forcing the Bavarian 2nd Division back three times and taking 200 Bavarians captive. At 4 pm, Wrede launched his attack on Hanau. The Austrian 14th Infantry Regiment stormed and smashed down the Nuremburg gate, creating an opening for those following behind them. Wrede rode through the gate at the head of a battalion of Austrian grenadiers, driving Fontanelli’s Italians through the streets of Hanau back to the Kinzig bridge. A group of Italian soldiers fled Hanau, only to be pounced upon by the Székler Hussars, who had been lurking outside the town walls. Hanau’s citizens huddled in their homes as brutal street fighting erupted around them.

Just as Wrede and the Austrian grenadiers reached the Kinzig bridge, Morand’s waiting artillery battery opened fire on them, inflicted terrible losses on the grenadiers, who were tightly packed into Hanau’s narrow streets. Wrede fell with a stomach wound while trying to rally the Austrians, while his son-in-law and aide de camp, the Prince of Oettingen, was killed in the French bombardment. As snow began to fall, Wrede’s other aides gathered up their fallen leader and carried him away from danger. Fresnel took command of the army and ordered a retreat.

Under cover of an artillery barrage, Bertrand pulled IV Corps out of the embattled town by 7 pm. The Battle of Hanau was over. The fight had cost Napoleon less than 1,000 casualties, although he had lost around 9,000 men since leaving Erfurt. One of the more noteworthy French soldiers killed in action was Assistant Adjutant Major Jean Guindey of the Grenadiers à Cheval, famous for killing Prussian Prince Louis at the Battle of Saalfeld in 1806. Wrede lost around 9,250 men in the two-day engagement, mostly due to the terrible deployment of his army. Napoleon proved again that he could still defeat a badly deployed enemy while at a numerical disadvantage. Wrede proved that a brave and ambitious commander could not always overcome tactical deficiencies despite a numerical advantage. Even though Hanau was a minor engagement to the French, to the Bavarians it was the first time they had taken the field against the French emperor. Wrede was later awarded with the highest decorations from Austria, Prussia and Russia in recognition of his sacrifice at Hanau. The Russian Cossacks were less appreciative—they robbed Wrede’s wife as she traveled to Hanau to take care of her husband.

At 7 am on November 1 Napoleon reviewed the Imperial Guard in Frankfurt, hearing the cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” for the last time in Germany. The Grand Army began crossing the Rhine into France, hoping to find some much-needed provisions in Mainz. In this, they were soon disappointed. To make matters worse, dysentery and typhus were spreading through the French ranks, sending hundreds to the hospital. The soldiers of the Grand Army hoped that Napoleon would negotiate peace with the victorious Allies. On November 7, the emperor left for Paris, intent on conscripting a new army for the following year’s campaign to be fought in France itself. Napoleon’s tired soldiers were disappointed by the prospect of the war’s continuation into 1814, but relief finally came with Napoleon’s abdication that April.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments