By Bob Cashner

Norway had been able to avoid the massive bloodletting of World War I entirely and fervently hoped to steer clear of World War II as well through a policy of strict neutrality. Having seen the fate of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, by 1940 many of Europe’s smaller and traditionally neutral nations were struggling to strengthen and modernize their military defenses. Norway had waited until almost the last minute before beginning a rearmament program and was ill prepared militarily to even enforce its own neutrality in Norwegian waters.

Tonnage wise, in 1940 the Royal Norwegian Navy was roughly only one quarter of the size it had been in 1914. It had only two capital ships, the armored coastal defense ships Norge and Eidsvold, whose keels had been laid before the turn of the century. The handful of new vessels available were mostly small patrol boats better suited to fisheries protection and enforcement than naval warfare, and there had been no money in the defense budget for the fleet to actually put to sea and conduct maneuvers since 1918.

In theory, with a full-scale mobilization and call up of the reserves, Norway could field an army of six divisions, but in peacetime each division had only a single active-duty battalion. The country did have a long tradition of universal conscription; young men coming of age had to serve a stint in the military. The basic training period, however, was the shortest of any nation in Europe, only 72 days. Some older reservists who had met their military obligation during the 1920s had received only 48 days of training. Even if there were time available to mobilize all the reserves, weapons and equipment were often both old and in short supply. The Royal Norwegian Army of 1940 did not have a single tank, antitank gun, or even hand grenades; there were not even enough steel helmets or rifle bayonets to go around in the case of full mobilization.

The Army Air Corps had a grand total of 62 aircraft, of which fewer than 20 could charitably be considered modern; the backbone of its fighter strength consisted of a dozen British-made Gloster Gladiator biplanes stationed near Oslo, and the most numerous attack plane was the 1924-vintage Fokker C.V.E., a wood-framed, fabric-covered biplane right out of World War I. The Royal Norwegian Navy had an additional 40 or so aircraft, but they were all of makes, models, and vintages that made the Army Air Corps seem state of the art. Norway had recently purchased some brand new L/60 40mm Bofors guns from neighboring Sweden, a grand total of eight of them. The vast majority of the country’s quite limited antiaircraft defenses consisted of aging World War I-vintage 75mm guns in fixed positions and of dubious value against modern, high-speed aircraft. The dozen 75mm luftvernkanon m/16 guns still in use in 1940, for instance, were a 1916 design originally designated as “antiballoon guns.”

So, when Allied and Axis nations alike looked at Norway’s 1,000-plus miles of strategic coastline and her vital rail link to the Swedish iron ore mines at the port of Narvik, neither were too concerned about the military repercussions of violating the country’s neutrality. The proposed joint British and French expeditionary force supposedly intended to go to the aid of Finland during the 1939-1940 Winter War was little more than a thinly veiled scheme to occupy Narvik and the Swedish iron mines. The Germans had torpedoed ships in Norwegian territorial waters. The British responded by chasing down and boarding the German merchantman Altmark right in front of a Norwegian patrol boat.

The Nazi German invasion of Norway was in fact hastened along by German Chancellor Adolf Hitler’s fears that the British were going to land troops there. German preparations for the invasion and occupation of Denmark and Norway were already being developed under the codename of Operation Weserübung.

Even though the Norwegian military was not well prepared, the Germans knew they had to strike hard and fast to achieve an early knockout blow. Hitler was already planning to invade France and the Low Countries, so the Germans could not afford to have men and material tied up in a lengthy campaign in Norway. If Norway determined to fight and was able to fully mobilize, the country’s rough, mountainous terrain offered a great many natural defensive positions, and given time the Norwegian military would be joined by British and French reinforcements. Thus, a major part of Operation Weserübung called for special detachments of troops to capture the Norwegian king, the prime minister and his cabinet, and leading members of the Storting (Parliament) within the first few hours of the invasion. It was hoped that the captured leaders, surprised and disheartened, would quickly capitulate and the Nazi conquest of Norway would become a fait accompli before the British and French could even respond.

Operation Weserübung, as it pertained to Norway, was a particularly audacious and far-reaching plan, almost to the point of recklessness; Adolf Hitler chortled that it was the “sauciest” military operation in history. It required a very tight timetable and close coordination between all three branches of the German military, the Heer (Army), Kriegsmarine (Navy), and Luftwaffe (Air Force). To achieve complete surprise, all the German landings would have to occur simultaneously over nearly 1,000 miles of coastline. Seaborne landings were slated for the Norwegian capital of Oslo and the important coastal cities of Bergen, Egersund, Kristiansand, Trondheim, and Narvik, while two airborne assaults would seize vital airfields at Stavanger and Fornebu. Wesertag (Weser Day) was finally set for April 9, 1940, and H-hour was 0500.

Bound for the Norwegian capital of Oslo was Warship Group 5, composed of German Navy vessels under overall command of Rear Admiral Oskar Kummetz, whose flagship was the brand new heavy cruiser Blücher. This group also included the Deutschland-class heavy cruiser Lützow, a 14,000-ton vessel sometimes termed a “pocket battleship,” sporting a main armament of six 11-inch (280mm) guns in two triple turrets, and the older 1920s-vintage light cruiser Emden, armed with eight 6-inch (150mm) guns. The remainder of Group 5 consisted of three torpedo boats, eight minesweepers, and two whalers. These ships carried a landing force of just over 2,000 troops from the 163rd Infantry and 3rd Mountain Divisions. An additional 23 merchant ships were standing by in German ports or at sea awaiting the word to bring in 14,000 more troops and their vehicles and heavy weapons once the Norwegian defensive installations along the Oslofjord were cleared.

The heavy cruiser Blücher was the pride of Nazi Germany’s new Kriegsmarine, one of its finest and newest ships, built in repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles and at a cost of nearly 86 million Reichsmarks. The second of five Admiral Hipper-class heavy cruisers, Blücher was commissioned into the fleet in September 1939, even as the panzers were rolling into Poland, and she had not finished her sea trials until April 5, 1940. Grossing 18,000 tons fully loaded, she was more than 675 feet long and had a beam of 72 feet. Her three Blohm & Voss 132,000 shaft horsepower steam turbines could drive her at a top speed of 32 knots, and she was crewed by 1,382 officers and men. Her main armament consisted of eight 8-inch (203mm) SK C/34 rifled guns mounted in twin turrets fore and aft. Secondary armament included a dozen 4.1-inch (105mm) guns, a dozen 37mm, eight 20mm light antiaircraft guns, and six 21-inch torpedo tubes port and starboard. For protection she carried three inches of belt armor, up to two inches of deck armor, and more than four inches of turret armor. Blücher normally carried three Arado Ar-196 float planes for reconnaissance and gunnery spotting, but on April 9 only two of the aircraft were aboard, one on the launching catapult and one in the hangar immediately aft of the funnel.

In addition to being Admiral Oskar Kummetz’ flagship, Blücher also carried Maj. Gen. Erwin Engelbrecht, commanding officer of the 163rd Infantry Division, and Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Sussmann, commander of the Luftwaffe’s ground organization for Norway. The 528 troops aboard included the special detachments designated to capture the Norwegian king and key government leaders, as well as the nation’s gold reserves. Stored topside above the main armored deck were light field guns and some 31 tons of munitions belonging to these ground troops.

The sea approach to Oslo is via the 100-kilometer-long Oslofjord, a restricted, winding, and often narrow waterway that affords ships little room to maneuver. Norwegian coastal fortifications dotted the shores and islands of Oslofjord for its entire length; collectively, these defenses were known as Oslofjord festning, or Oslofjord Fortress. A natural defensive bottleneck forms in the fjord at Drøbak Sound, where the channel briefly narrows down to a little over a quarter of a mile wide, and the Drøbak narrows are the dividing line between what is known as Inner and Outer Oslofjord. Two small islands at the narrows were home to Oscarsborg Fortress, which would play a large role in the events of April 9, 1940.

Luck initially seemed to be with the vessels of Warship Group 5 as they penetrated the outer mouth of Oslofjord late on the night of April 8, 1940; a thick fog hung over the water, concealing the German ships. Rear Admiral Kummentz had issued orders for his ships to hold their fire unless otherwise ordered by the flagship and to ignore any warning shots from the Norwegian defenders.

At around 2300 hours, the Royal Norwegian Navy patrol boat Pol III, a small former whaler with a crew of 15 and armed only with a single 76mm gun, came across the wakes of Warship Group 5 and began to follow them. She was discovered by the German torpedo boat Albatross, which closed on the Pol III and ordered the crew at gunpoint not to use their radio transmitter. Captain Leif Welding-Olsen refused and became the first Norwegian military casualty of World War II. In the tense situation in the fog, the two ships collided, the smaller Pol III taking the lion’s share of damage as she fired a single warning shot and then launched one white and two red flares, the warning signal for enemy ships in Oslofjord.

Albatross backed off and took her under fire, immediately knocking out her sole gun. The crew abandoned ship. Captain Welding-Olsen had lost both his legs, and, seeing the lifeboat was already overloaded, bade his men farewell and rolled himself overboard. Coastwatchers and another small Norwegian patrol boat radioed warnings to Oslo.

Alerted by Pol III’s flares, the Norwegian battery on Rauoy Island spotted Warship Group 5 and fired a blank warning round and then five live rounds from its 150mm guns. The latter shots were fired in anger, but in the fog and darkness Rauoy’s outdated fire control and sighting systems did not prove up to the task. The shells fell so far astern of the Kriegsmarine warships that the Germans actually assumed all six shots had been blanks. Fort Bolaerne also fired a warning shot that went unheeded.

After this brief flurry of fire, Warship Group 5 disappeared into the mist. The Germans were still on schedule and had suffered no damage. At 2345, the flotilla halted briefly as landing parties were put aboard six of the minesweepers to capture Forts Rauoy and Bolaerne and the small Norwegian naval post at Horten, from the rear. The bulk of the warships then proceeded farther up the fjord.

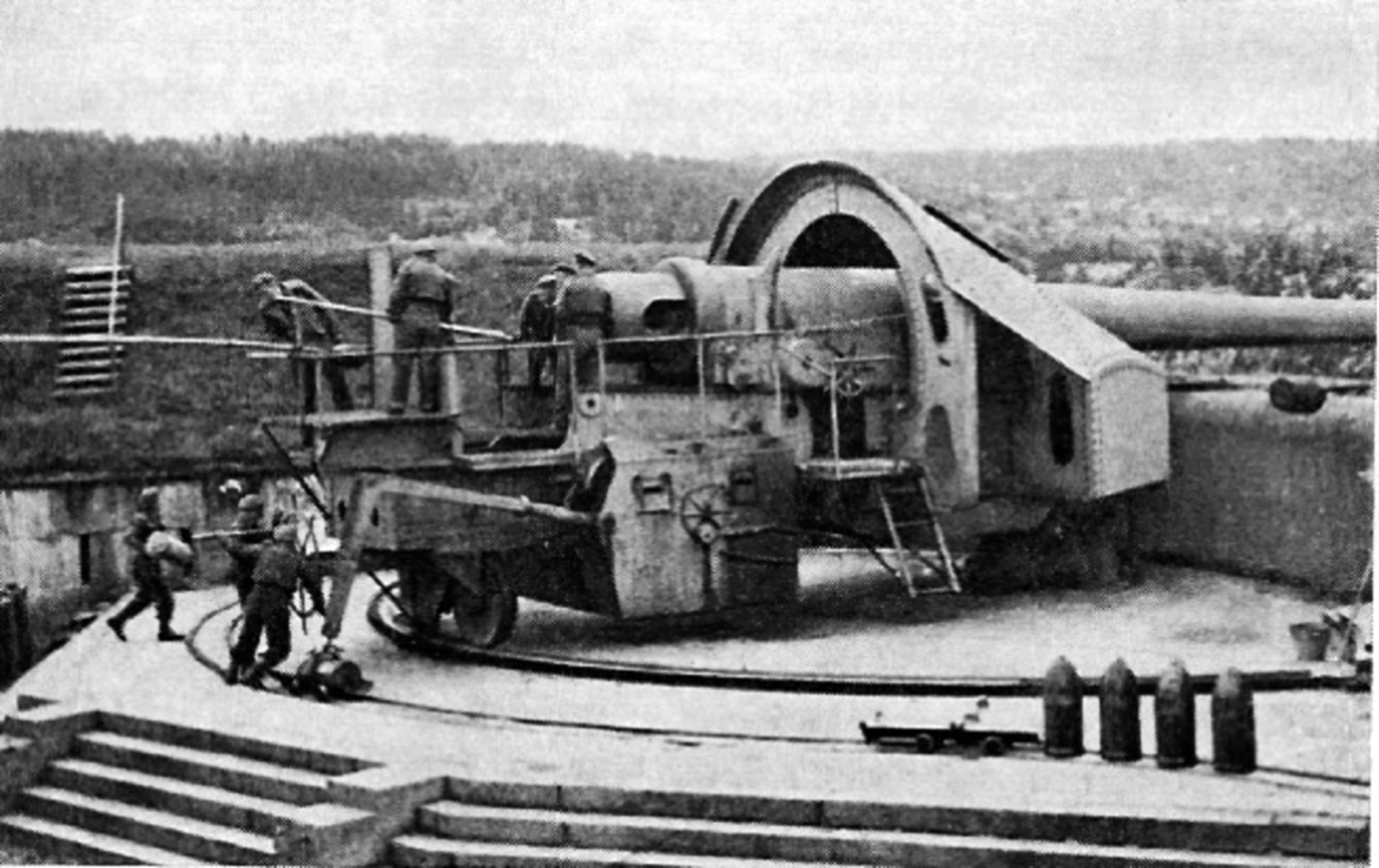

By 0415 hours on the morning of April 9, Warship Group 5 was approaching the Drøbak narrows and Oscarsborg Fortress. By at least one account, German charts listed the old fort as a museum rather than an active coastal defense site. Originally completed in 1855 on South Kaholmen Island, the brick and mortar structure was named after the visiting Swedish-Norwegian King Oscar I. It had been modernized toward the end of the 19th century. In 1879, an underwater barrier was completed that restricted the passage of large, deep-draft ships to the eastern channel of the fjord. In 1893, the new Main Battery armament, three Krupp Model 1891 11-inch (280mm) L/11.2 coastal guns, was purchased from Germany and installed. While cranes were originally unloading the Krupp guns from their ship for installation in the fortress, one of the massive 28-ton cannons had accidentally been dropped into the fjord. After being fished out of the water, the gun had been christened “Moses” and the other two guns in the battery were then named “Aaron” and “Joshua.”

Since the battery was constructed prior to the age of air power, the Krupp guns were mounted in open-topped barbettes; their concrete and earthen embankments could only protect the weapons from the flat-trajectory direct fire of enemy ships.

Just as important as the Main Battery to the events of that fateful morning was the Torpedo Battery on tiny North Kaholmen Island, which had been completed in 1901. Situated entirely underground, the interior of the battery had been carved out of the island’s granite bedrock and featured three interior elevators that launched torpedoes underwater via concrete tunnels. The above-ground concrete slits that allowed aiming of the fire control mechanisms were well camouflaged by hedges, and this battery was one of the few Norwegian installations that was completely unknown to German intelligence. The battery’s nine 17.7-inch (450mm) diameter Whitehead torpedoes had been manufactured in Fiume in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1900. They were cold-running torpedoes that used a 3-cylinder reciprocating engine that ran off compressed air with a speed of 27 knots and a contact-fused 220-pound explosive warhead. Although the weapons were tested at intervals over the years, no one was absolutely sure how well or even if they would still work if fired in anger.

Lastly, two fortifications on the east shore of the fjord opposite Oscarsborg were under the command of Captain Vagn Enger. Situated atop a hill overlooking the fjord, Kopås Battery had three British-made Model 1899 Armstrong 6-inch (150mm) guns and two searchlights. Much lower and close to the shoreline was Husvik Battery, which had only two old 19th century Cockerill-Nordenfelt Quick-Firing 6-pounder (57mm) mine barrier protection guns intended for use against small craft attempting to sweep the minefield.

When fully manned, the combined defensive fortifications throughout Oslofjord Fortress should have had a total garrison of 1,433 enlisted men and 210 officers. On April 9, only 613 men and 83 officers were present. Of the 613 enlisted men, 450 were fresh recruits who were just beginning to undergo their training. The naval minefields had not been deployed because planting the mines was to have been part of the recruits’ training in the near future.

In command of Oscarsborg Fortress was 64-year-old Coastal Artillery Oberst (Colonel) Birger Kristian Eriksen, only six months from retirement. Present for duty under his direct command at the Main Battery were 28 officers and men, but only enough trained artillerymen to man one of the big Krupp guns, which required a crew of 11. Eriksen divided his single gun crew in two then leavened each half with the garrison’s cooks, clerks, and drivers, who had been awakened from their barracks, and a handful of reservists who had shown up on their own initiative. By doing so he was able to fully man two of the main guns, Moses and Aaron, although all three were loaded under his direct supervision.

Colonel Eriksen may not yet have known for certain the nationality of the approaching ships, but he knew they were hostile and that numerous warning shots had already been fired in Outer Oslofjord. If he fired a warning shot of his own, it was doubtful the scratch gun crews could reload the ponderous ancient weapons in time to fire another. He let the approaching ships come to within point-blank range, approximately 1,300 meters, so that there was little chance of missing. The thought that by firing his guns he might well be starting a war must have weighed heavily on his mind. When a junior officer questioned him about his order to commence firing, his famous reply was, “Either I will be decorated or I will be court martialed…. Fire!”

Moses and Aaron spoke, their massive muzzle blasts briefly lighting up the gloom and their heavy booms echoing across the fjord. Aboard Blücher, Captain Kurt Zoepffel recalled, “Suddenly, an ear-splitting roar of thunder rends the air. The glare of the guns pierces the darkness. I can see three flashes simultaneously. We are under fire from two sides; the guns seem only 500 yards away. Soon bright flames are leaping from the ship.”

Both shots were hits. The first 562-pound high-explosive shell crashed into Blücher’s forward superstructure above the bridge, killing and wounding several men. Moments later, the second 280mm round struck Blücher’s seaplane hanger amidships. The Arado seaplane in the hangar and the aircraft on the catapult were fully fueled, and both were almost immediately engulfed in roaring flames as the volatile aviation fuel ignited. This in turn began to explode the army munitions stored on deck, disabling one of Blücher’s portside 4.1-inch guns.

Blücher immediately returned fire with her secondary armament of 4.1-inch guns and light 37mm and 20mm flak batteries. Not believing his improvised gun crews could manage to reload Moses and Aaron under fire, Colonel Eriksen ordered his men to simply take cover. There was no reprieve for Blücher, however. In response to the Main Battery firing, the Kopas and Husvik Batteries on the east shore of the fjord opened fire as well. Situated on the high ground, Kopas’ three 6-inch Armstrong guns delivered plunging fire onto Blucher’s decks. Most of the shells failed to penetrate Blücher’s deck armor, but the repeated strikes created chaos. The munitions stored on deck began to explode, igniting more fires; a starboard 4.1-inch gun was knocked out, massive power failures flickered through the ship, and rudder control from the helm was damaged. Blücher took a total of 13 hits from the 150mm guns and 30 from the rapid-fire 6-pounders. The 57mm guns of Husvik Battery had to be abandoned by the Norwegian gun crews as Blücher passed, her flak guns firing directly into the shoreside weapons pits.

Following Blücher 600 yards astern, Lützow immediately opened fire toward the Norwegian shore batteries with her 5.9-inch secondary batteries and began to swing her forward 11-inch turret onto the target. As she did so, three 150mm shells from Kopas Battery struck her in rapid succession. One scored a direct hit on “A” turret, wounding several sailors and putting the turret out of action. Another impacted the ship’s sickbay, killing two men and wounding many others and starting a fire. Lützow also took several hits from the rapid-fire 57mm guns of Husvik Battery and was being raked by machine-gun fire from shore even as her captain and crew observed the massive explosions and sheets of flame erupting from Blücher ahead.

Captain August Thiele ordered the pocket battleship to withdraw, forcing Emden to avoid a collision. Although Lützow’s crew quickly extinguished her fires and soon had two out of the three 11-inch guns in “A” turret operating again, the fog did not allow them to impact the fate of Blücher.

When the Norwegian guns had initially opened fire, Captain Zoepffel aboard Blücher had rung up full speed and steered for the middle of the channel. This soon took the cruiser out of the line of fire from the shore batteries but unknowingly put it square in the sights of the concealed Torpedo Battery. Since the commanding officer of the torpedo battery was on sick leave, a retired senior commander who lived in nearby Drøbak had been given temporary command in March 1940. Sixty-one-year-old Kommandørkaptein (Commander Senior Grade) Andreas Anderssen was the perfect choice; he had first served as a young officer on the Torpedo Battery in 1909 and later retired as its commander in 1927, so he knew the weapons and equipment inside and out. The two officers and nine seamen under his command were all longtime reservists who were also knowledgeable and well trained when it came to operating the battery.

Anderssen gave the command to fire two torpedoes, and both of the elderly fish ran straight and true. One hit Blücher forward of amidships and the other toward the stern, rocking the cruiser with two more massive explosions on the port side.

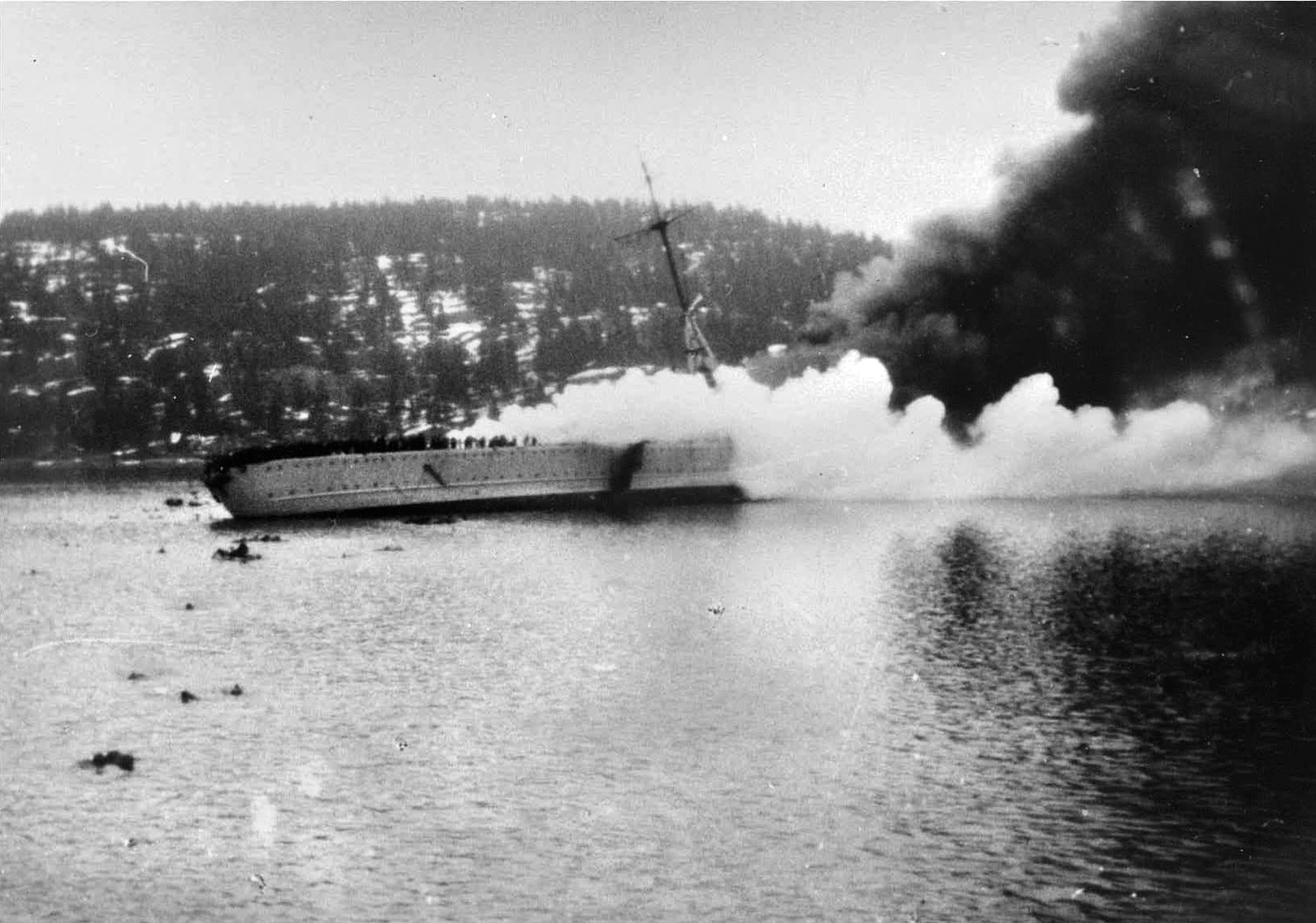

Although she had taken on a 10-degree list and lost steering as her engine rooms began to flood, Blücher was not yet mortally wounded. No longer taking any Norwegian fire, she dropped anchor to keep from drifting into the shoreline as the crew fought to extinguish her fires. The fire in the floatplane hangar, however, had grown to an inferno and spread to several decks below. On deck, the army’s small arms ammunition and grenades were continuously cooking off, scattering the firefighting crews and shredding the fire hoses with shrapnel. The fires exploded four 100-pound bombs in the floatplane hangar, and great clouds of black smoke and hissing steam were gushing from the ship’s funnel and the gaping hole amidships.

At 0530, the fires reached Blücher’s amidships ammunition magazine for 4.1-inch ammunition. The resulting explosion ripped a great hole in her side, ruptured the bulkheads between boiler rooms, and blew open her fuel bunkers, exposing the fuel oil to the raging flames. This damage sounded the proud new cruiser’s death knell. At 0600 the order to abandon ship was given. The Blücher slowly rolled over and sank 22 minutes later. At least 125 of her crew were lost along with 200 of the 528 soldiers in the landing parties.

Still unaware of the hidden underground Torpedo Battery, Captain Thiele of the Lützow believed that the Drøbak Narrows were heavily mined and it was these weapons that had sunk Blücher. He ordered Warship Group 5 back down the fjord, out of range of Oscarsborg’s ancient guns, although Lützow was able to continue firing on the forts with her modern long-range 11-inchers. Instead of being landed directly into Oslo’s harbor as planned, the remaining troops aboard the vessels of Warship Group 5 now had to be landed in the small town of Son, some 25 miles away.

With daylight came the Luftwaffe. Wave after wave of Heinkel He-111 twin-engine bombers swooped over the islands, dropping 440-pound bombs on the fortifications. Two of Norway’s eight new 40mm Bofors guns replied along with a handful of Colt M/29 7.92mm machine guns, but the limited antiaircraft defenses failed to down any German bombers. The skies cleared from noon until 1330 while Lützow returned to bombard the fortress with her 11-inch guns. Afterward, more German planes, including Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers, returned to blast the fort. Oscarsborg Fortress was subjected to aerial bombardment for almost nine hours and was hit with approximately 500 bombs.

Despite the successful resistance of Colonel Eriksen and his men, Oslo was captured before the end of the day on April 9 by German infantry airlifted into Fornebu Airport, which had been captured earlier by paratroopers. After the aerial bombardment and with German troops ashore on both sides of the fjord, Colonel Eriksen decided not to subject his handful of ill-prepared troops to an infantry assault and surrendered Oscarsborg on the morning of April 10.

By sinking Blücher and forcing the remainder of the German task force to land its troops miles from the capital, the Oscarsborg garrison had bought time for the king, prime minister, cabinet, and parliament to be evacuated on a special train from Oslo to Elverum, where the Storting reconvened and vowed to fight. The country’s gold reserves were smuggled out of the capital to the town of Lillehammer.

Instead of handing the Norwegian government a fait accompli, the Germans wound up having to devote further men and resources to a lengthy campaign. With most of the major Norwegian cities in German hands, the Norwegian Army reservists were never able to fully mobilize, but those units that did fought on and were joined by British, French, and Free Polish troops.

In the final reckoning, however, British control of the sea was trumped by German control of the air. The Allies later evacuated their expeditionary forces from Norway, and the last Norwegian Army units laid down their arms on June 9, 1940. The fight for Norway had lasted for two months, longer than the Germans had expected, and the loss of the new Blücher was a severe blow to German prestige.

Author Bob Cashner resides in Philipsburg, Montana. He has previously written for WWII History on the Boys Anti-Tank Rifle, War Dogs, and the Japanese knee mortar.