By Pierre V. Comtois

Close to the northern end of the island of Tokashiki, the largest member of a tiny group of islands called Kerama Retto, located 15 miles west of Okinawa and hardly 400 miles from the Japanese home islands, Corporal Alexander Roberts and the rest of the 306th Regimental Combat Team rested for the night beneath the starry skies of the northern Pacific. It was a welcome respite from the previous three days of tension-filled landings and clashes with resisting Japanese troops.

Suddenly, the eerie silence of the night was interrupted by a series of dull explosions and the subsequent screams and wails of the injured from farther inland. The next morning, Roberts and his fellows, in seeking out the source of the sounds, discovered a small valley filled with over 150 dead and dying Japanese civilians. As a result of official warnings of the barbarous practices of the invading Americans, fathers had throttled their families before disembowling themselves. In some places, three generations lay mangled together beside the bodies of their patriarchs who themselves had been torn apart by the self-inflicted blasts of hand grenades. As the American soldiers did what they could dispensing food and medical care, survivors who had killed their loved ones only hours before wept with the realization of the enormity of their error.

Such a scene was only the beginning of the tragedies to be visited upon the Japanese people already overburdened with the human cost of years of war. The toll in human lives would only escalate as the titanic struggle for the Pacific entered its final phase and the desperation of Japan’s military leaders led them to envision a final stand involving every last member of their beleaguered nation.

Rolling Up the Empire of Japan

By late 1944, the ring of steel thrown up around the crumbling Empire of Japan had begun to tighten to the point where regular bombing of the home islands and territories long held by the Japanese became the norm and future amphibious operations by the United States moved to targets considered by the enemy as its native soil.

Events began to move faster with the fall of the Philippines at the end of February 1945, and with the invasion and conquest of Iwo Jima by mid-March. Vast naval task forces roamed the waters off China and Japan while American warplanes ruled the skies and its submarines prowled beneath the seas.

As early as October 10, 1944, warplanes made the first fast-carrier raid on Okinawa, destroying Naha, its most important city. When the Philippines were invaded on January 8, 1945, Vice Admiral John S. McCain’s Task Force 38 moved north to cover the operation, ranging far afield in the performance of its duties. During that time, TF 38 savaged the Ryukyus, struck Formosa, and laid waste the ports of the South China coast.

Finally, with the Philippines declared secure by an overly optimistic General Douglas MacArthur, McCain turned his ships back to Ulithi Atoll in the Palaus, where he and Admiral William H. Halsey turned over the Pacific Fleet’s command to Admirals Raymond Spruance and Marc A. Mitscher. With the transfer of command, the Third Fleet became the Fifth, with Task Force 38 metamorphosing into the new Task Force 58 whose mission would now be to mount, launch, and support the coming strikes at the Ryukyu islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Operation Iceberg would be the culmination of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s island-hopping campaign that had taken the United States Navy and Marine Corps, in three years, all the way across the Central Pacific. Now, with Nimitz himself headquartered at Guam and the elements of what would become the greatest naval armada ever assembled being outfitted at their various staging areas from California to Australia, the Americans were poised

to enter their end game with Japan.

After the reduction of Iwo Jima on March 14, 1945, square in the sights of this American juggernaut was the tiny island of Okinawa, the anchor at the end of a long chain of outer islands that led 400 miles back to Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese home islands.

Kerama Retto: Strategic Territory Near Okinawa

Not unaware of Okinawa’s exposed and strategic position, Tokyo had arranged for 100,000 men of the 32nd Japanese Imperial Army to welcome the advancing Americans with lead, steel, and fire. By this point in the war, the Japanese high command knew they had everything to lose; they knew with what implacability their enemy was coming for them.

The one straw to which they might grasp was the hope that by making each further step closer to the home islands as costly as possible, they might be able to negotiate an end to the war that would involve something less than unconditional surrender.

For their part, the Americans also realized the strategic importance of Okinawa as a base from which to launch air strikes at Japan and to prepare for its inevitable invasion. With their recent experience on Iwo Jima, the American commanders knew what kind of reception awaited them on Okinawa and planned accordingly. A landing force of 157,000 Marines would challenge the Japanese ashore while an awesome fleet composed of over 1,500 warships would lie off shore and range the wide western Pacific in their support. But, before this force was brought to bear upon its target, a small but necessary side show would first have to be performed.

As the battle for Iwo Jima progressed, the difficulties in resupply and reenforcement of the troops ashore became more and more acute. With the growing threat of kamikazes possibly forcing any naval covering force out to sea and away from direct support of the landward fighting, the advantages of establishing some kind of permanent supply base close to the invasion beaches in any future operation were evident.

As L-day for Operation Iceberg approached, Vice Admiral Kelly Turner, commander of the Joint Expeditionary Force designated TF 51, suggested the seizure of a tiny group of islands 15 miles west of Okinawa called Kerama Retto, the largest and most easterly of which could host a two-mile-long runway for seaplanes and a sheltered, deep water anchorage that could hold as many as 75 ships.

At first, Turner’s suggestion was dismissed as unfeasible due to the islands’ vulnerability to enemy air attack from at least five nearby air bases, but as time went on Turner won support for his idea. Planned to take place just six days prior to the invasion of Okinawa itself, Turner hoped that the fleet’s covering fire throughout the Ryukyus would divert Japanese attention from Kerama Retto, enabling him to seize the islands with a relative handful of troops.

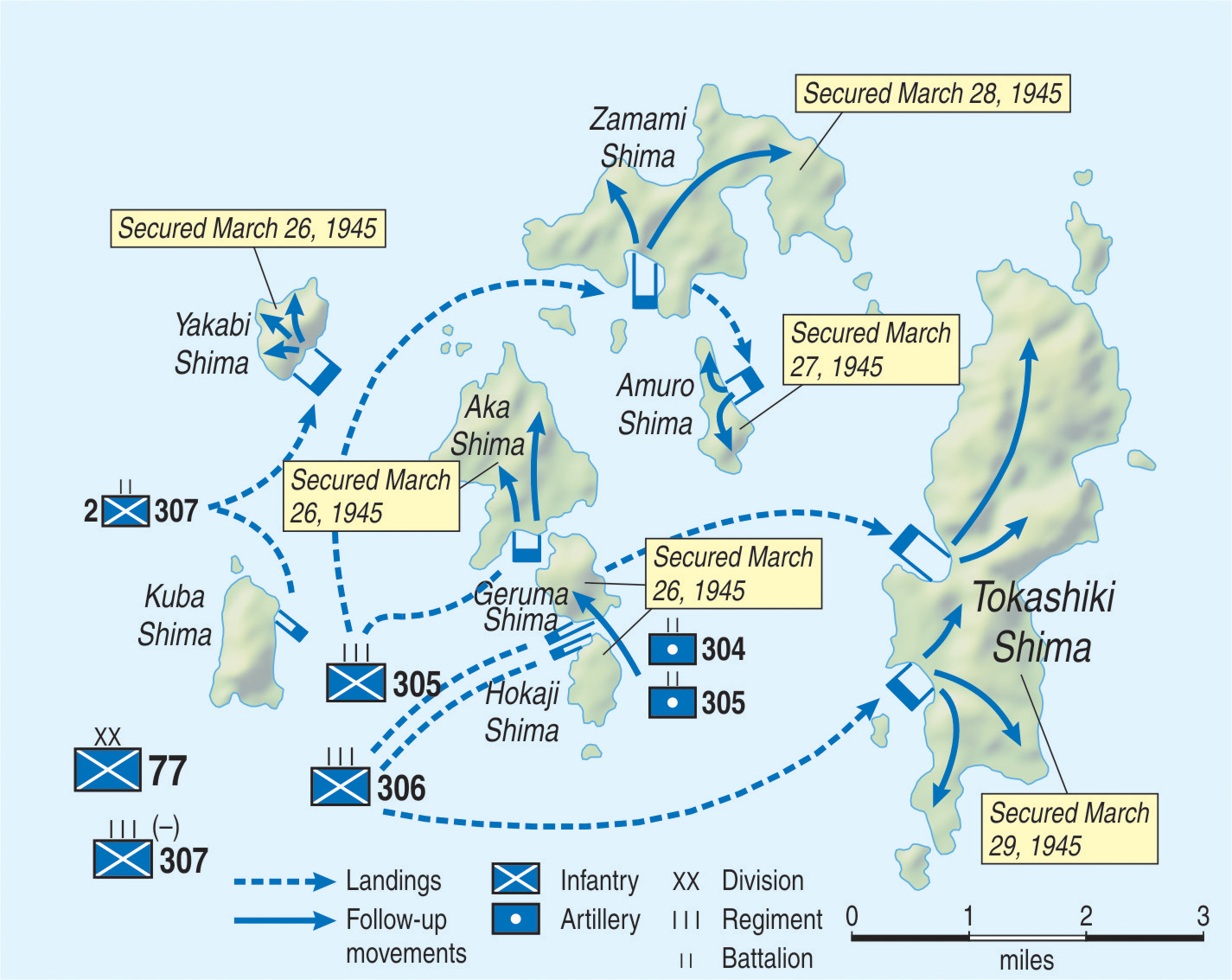

The American Invasion Force

Chosen for that job was XXIV Corps’ 77th Infantry Division. Veterans of the Philippines fighting, they were involved with the conquest of Leyte and were ramrodded by Major General Andrew D. Bruce. As the operation unfolded, the 77th would break up into four Battalion Landing Teams (BLTs) and assault each island in the Kerama group simultaneously. In addition, the 420th Artillery Group would land on tiny Keise Shima, about halfway between Kerama and Okinawa, where their guns would be within range to support the coming landings on the Hagushi beaches.

Of course, much of the plan relied upon the Japanese not expecting an attack from such an unlikely quarter and, in that expectation, the American planners were not disappointed. Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, the commanding officer of the Japanese on Okinawa, was convinced that the Americans would not waste their strength or allow themselves to be distracted in taking Kerama Retto. So, in dire need of every fighting man he could get, Ushijima ordered the islands stripped of the 2,335 soldiers stationed there. That left behind a gaggle of 975 men from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Sea Raiding Squadrons and Base Battalions, as well as Korean slave laborers of the 103rd Sea Duty Company.

Despite the weakness of the remaining force, Ushijima still had plans for the Kerama Islands, intending to use them as a base for 350 explosive-laden suicide boats that would be launched against the ships of the American landing force.

While the 77th Division assembled on Leyte in mid-March to begin practicing for the operation, its commanders were meeting to hammer out the final details of the plan, including study of last-minute air reconnaissance photos taken by Army planes from nearby Luzon, which showed a number of inviting beaches for the landing craft. The pictures also revealed the rather bleak terrain of the islands of Kerama Retto, which covered no more than an area of about 16 square sea miles. Rocky and uneven, the islands comprised narrow defiles and craggy cliffs covered in a desultory layer of scrub brush and gnarled trees. The narrow beaches of coral rock were squeezed at the end of steep valleys with low sea walls to protect them from the tide. The population of just over 6,000 people existed with a few pack-animal trails and no roads, making a living from the sea rather than from their steeply sloped plots of sweet potatoes on the islands’ rocky hillsides.

From March 18-20, the 77th completed loading duties and embarked into its various landing craft. Slowly, inexorably, all the elements of TG 51.1 began coming together as Rear Admiral Ingolf N. Kiland took the Western Island Attack Group out to sea on March 21. From there, aboard his flagship Mount McKinley, Kiland could observe his entire command: a 19-ship transport squadron with their attendant destroyers and destroyer escorts, a tractor flotilla of 29 large landing craft, gunboats and patrol ships, a hospital ship, two repair ships, two Victory ships filled with ammunition, an antimine group with their nets and buoys, tankers, and a whole range of miscellaneous surface craft that included two tug boats. In short, Kiland had everything he needed to make a proper, self-contained island assault.

Protecting Kiland’s group in the wider seas around him ranged the escort carriers and minesweepers of Rear Admiral William “Spike” Blandy’s Task Force 52, which also included underwater demolitions teams. And beyond Blandy were the rest of Turner’s Joint Expeditionary Force and Mitscher’s Task Force 58.

The Intensified Bombing Campaign

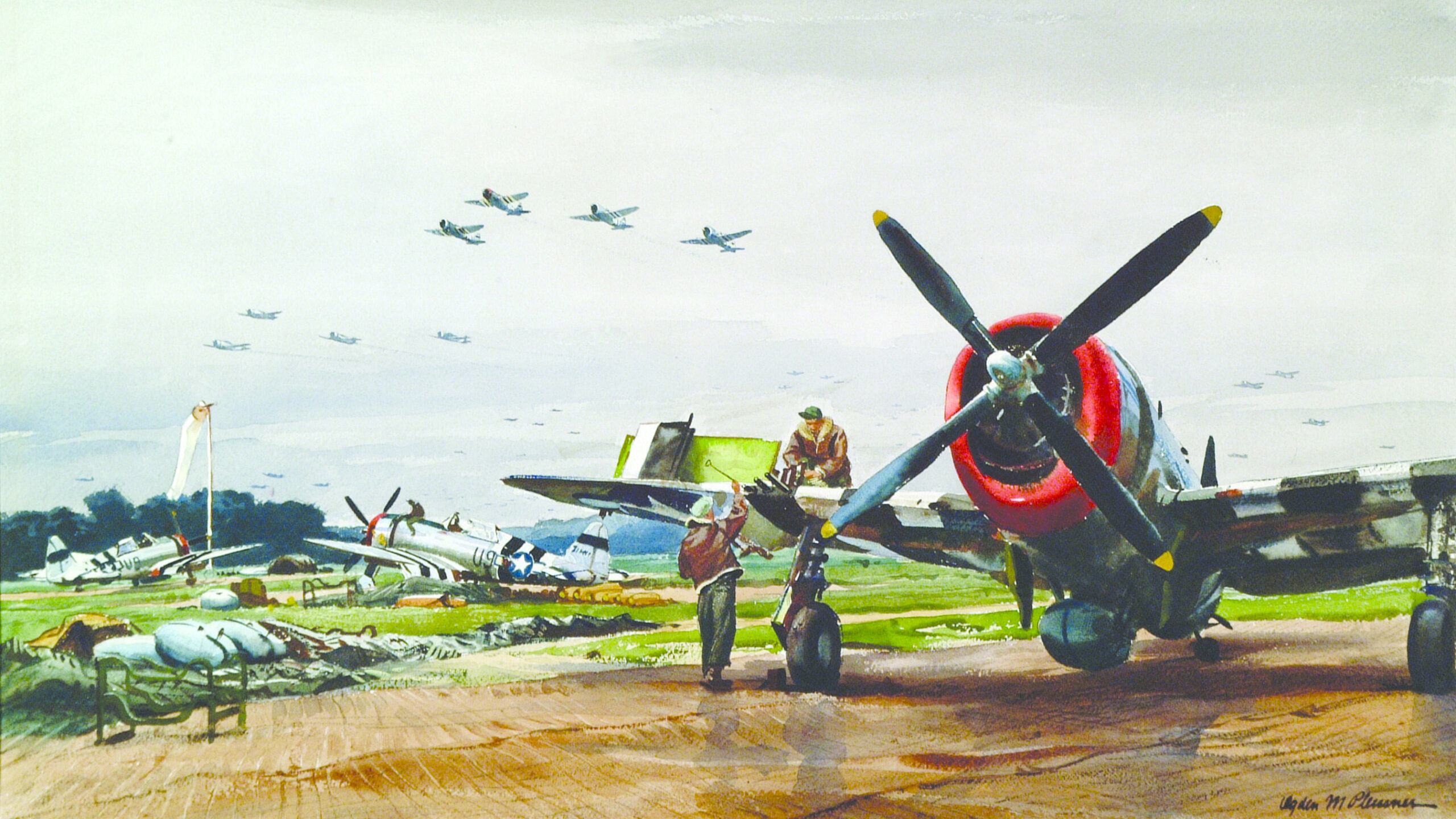

In the meantime, offensive activity against the enemy had intensified all over the northern Pacific in preparation for the coming enterprise. American expectations were sanguine about the invasion of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. As a result, extensive softening-up operations were planned for.

As the new year began, Fast Carrier Task Forces swept the seas looking for targets of opportunity and brushed every enemy plane from the skies. One such group made an early raid on Okinawa, prompting an unnamed Japanese signalman there to write, “The ferocity of the bombing is terrific. It really makes me furious…. What the hell kind of bastards are they…. Bomb(ing) from 6 am to 6 pm!”

It was only the beginning. The air strikes became heavier and more frequent. When the carrier planes retired, they were replaced by waves of B-29s that pounded the island with such constancy that the hapless Japanese referred to them as the “regular run.” The relentless bombing of Okinawa was still going on in March when Marine flight leader Major D.C. Andre, flying over the island on a reconnaissance mission, marveled at the destruction. “I’d never seen so many planes over one target at the same time,” he said.

Beneath the seas and above the waves, enemy shipping was nowhere safe. Taking a cue from German tactics in the Atlantic, American submarines formed their own wolf packs and hunted down Japanese naval units wherever they could while aircraft did the same above the surface. In the first three months of 1945, Americans sank more enemy craft than any other naval force in history. Desperately needed reinforcements and supplies bound for the Ryukyus found only watery graves along the sea lanes between the home islands and the war zone.

In addition, the air war intensified to levels undreamed of only four years before. Even as thousands of warplanes continued to arrive from the United States on outlying islands, thousands more dominated the skies over Japan. Carrier-based fighters shot down every plane that dared rise to challenge them and destroyed hundreds more on the ground.

From bases all around Japan, in China and India, the Philippines, and Palaus and the Marianas, endless waves of American heavy bombers sought out industrial targets throughout the enemy homeland.

B-29 raids, numbering in the hundreds of planes, ruined the great cities of Japan. But the worst was yet to come. Dissatisfied with the performance of his bombers, General Curtis LeMay, commander of the 20th Bombardment Group, ordered 300 Superfortresses loaded with 2,000 tons of incendiary bombs and sent them over Tokyo on March 9. The resultant devastation could not be more complete, with over 16 square miles of the city reduced to ashes and almost 100,000 people killed.

Keeping the Enemy at Bay

As Kiland’s attack group continued to make its way through heavy seas and its inexperienced landing-craft crews poured over illustrated copies of The Coxswain’s Guide to the Beaches, elements of TF 58 kept the enemy at a distance. On March 23, the destroyer Haggard found a prowling Japanese submarine that Lt. Cmdr. V.J. Soballe immediately ordered depth charged. Forced to the surface by the sub-sea explosions, RO-41 breached just in time to be rammed by Haggard and sent to the bottom again in pieces.

The next day, Admiral Mitscher sent 112 planes on a strike against a Japanese convoy 150 miles northwest of Okinawa, sinking all eight ships.

In expectation of the imminent arrival of TG 51.1, the ships of Blandy’s Amphibious Support Force were already hard at work. By March 25, the 122-ship flotilla of destroyer minesweepers, motor mine-sweepers, tenders, and patrol boats had cleared a seven-mile-long corridor to Kerama from the south and another from the southwest. Although the Japanese never practiced extensive use of underwater mining except in Philippine waters, and what mines they did use were antiquated and inefficient, there were still plenty to give the U.S. Navy headaches.

Aboard his flagship Terror, Rear Admiral Alexander Sharp coordinated his fleet of minesweepers as they searched the approaches to the Kerama beaches for their dangerous prey, fighting off sniper fire from shore and the harassing kamikazes from the air. On the day of the Kerama landings, the destroyer Halligan struck a mine in unswept waters and had its entire bow blown off.

Early on the morning of March 25, after the surrounding waters had been cleared of mines, Rear Admiral C. Turner Joy left TF 54, the Gunfire and Covering Force, headed for Okinawa with two cruisers and three destroyers, and arrived off Kerama at 5:30 am. Immediately, Joy’s ships began a preliminary fire on the various islands, concentrating on the designated landing beaches and what strongpoints were judged to be of possible danger to the landing force. Joining him were other destroyers taking up positions around the islands for radar picket duty against the threat of enemy air strikes.

Frogmen Intelligence at Kerama Retto

At 6:00 am, the first Americans waded ashore at various beaches of the target islands, but they were not infantrymen––they were frogmen of Blandy’s Amphibious Support Force. The underwater demolitions teams (UDTs) broke up into three units, each delivered to its proper beach by an LCVP that churned its way to the islands’ outlying reefs, deposited its load of frogmen, and then turned back out to open water.

Dropped every 50 yards, the divers wore nothing but a pair of trunks, goggles, and flippers and carried only measuring lines and waterproof writing gear. In the gloom of early morning, they worked under an umbrella of gunfire from the destroyers offshore that helped keep enemy sniper fire to a minimum. Methodically working their way along the reefs, which sometimes came within inches of the surface of the water, the frogmen inspected the approaches to the beaches for underwater obstacles. At last, their inspection finished, they grabbed lines trailing from the stern of the returning LCVPs and were hauled aboard for the fast trip back to their command APDs and an analysis of their findings.

In the case of the Kerama operation, the news was not good, but hardly devastating to the operation. With the report from the UDTs of the impossibility of using LCVP landing boats on two of the target islands due to the unusually high coral formations, Kiland was forced to make a change in his invasion plans. Using LVTs, the islands of Zamami, Aka, Hokaji, and Geruma Shima would be assaulted by four battalions of the 77th as originally planned, but the attack on Yakabi and Kuba Shima would be delayed until the tractors used in the Aka landings could return to the flotilla. There, they would be reloaded with troops and diverted to the Yakabi and Kuba beaches.

A Surprise Landing on Kerama Retto

As the day dawned bright and clear on March 26, Kiland confirmed 8:00 am as M-hour for the invasion of Kerama Retto to begin. Already, two groups of LSTs had broken away from the main portion of TG 51.1, with the smaller group of four making its way two miles north of Yakabi Shima, the western most of the Kerama group, and the other group of 14 ships two miles south of Kuba Shima. By 6:40 am, as a curtain of support fire from cruisers off shore and carrier planes overhead bombarded the tiny islands, amphtracs with their payload of anxious troops and amphibious tanks began their run for the beaches. With Navy guide boats in the lead, the amtracs and amphibious tanks divided into their separate battalions and headed for their designated landing areas.

Their approach was made more difficult than beach landings usually were by their having to invade so many closely situated islands at once. The northern group of LSTs had to make two dog-legs before hitting their beach on Zamami; the southern group, after splitting up into three groups, needed to wind their way past tiny, reef-guarded islets to reach their assigned objectives. But the fact that all groups hit their proper beaches on schedule was proof of the landing crafts’ fast-learning crewmen.

As each assault wave neared its target, its accompanying support craft added their own firepower to that of the cruisers and strafing planes, with mortars coughing at 3,200 yards, rockets roaring at 1,100 yards, and automatic gunfire filling in the gaps. Gradually, as the troops neared shore, cruiser fire shifted away from their front to the flanks. At last, the support craft halted their approach to allow the landing craft through. At that point, they ceased their fire and retreated as the amphibious tanks took the lead and spearheaded the final dash to the beaches.

As it turned out, the operation took the enemy completely by surprise, with most of the landings being unopposed and the few Japanese defenders retreating inland to caves and tunnels, bringing the islands’ terrorized native inhabitants with them. The soldiers, who had been ordered by Ushijima to offer minimum resistance to any enemy attack, had regaled the civilian population with stories of the horrible fate that awaited them at the hands of the barbaric Americans.

Just four minutes after M-hour, the 3rd BLT of the 305th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) were the first Americans ashore on Kerama as their LVTs ran up onto Beach Gold at Aka Shima to a reception of mortar and machine-gun fire delivered by the 200 Korean laborers and Japanese suicide boat operators defending the shore.

Situated in the center of the Kerama group, Aka, or “Happy Corner Island,” was hardly 3,000 yards long and rose to about 600 feet at the summits of two small peaks, affording few hiding places for its defenders when they retreated without inflicting any harm on the Americans. Moving quickly, the GIs overran the tiny village of Aka and pressed inland where resistance increased. As the landscape rose higher, the Japanese offered greater and greater opposition. At one point, naval gunfire had to be called in to blast a platoon of enemy soldiers from the path of the advance.

In the afternoon, a total of 58 more Japanese were killed in a host of small-unit encounters, with every enemy soldier needing to be rousted from caves and prepared positions almost man to man. By early evening, however, most of the island had been secured. Yet nearly 300 Japanese combatants and 400 civilians were still holed up in what remained.

Nighttime Melee For the 2nd BLT

South of Aka, the smaller island of Geruma Shima was invaded by elements of the 306th’s 1st BLT coming ashore on Beach Yellow nearly a half hour after the 3rd landed on Aka. In contrast with Aka, however, this island was secured in a few hours, with the 304th and 305th Field Artillery Battalions’ 105mm howitzers soon being unloaded for use in the next day’s operations against Tokashiki.

The troops met some light sniper fire and found some abandoned pillboxes, but the handful of the island’s defenders were lying dead by the end of the day—a situation that was not regretted by some of its surviving civilians who were found after they had strangled members of their own families out of fear of what they had been told about the Americans and discovered afterward to be lies. Fortunately, however, not all of the natives panicked. A great many—in company with Korean forced laborers who’d escaped their masters—gave themselves up.

After the third island, Hokaji, had been seized without opposition by the 306th’s 2nd BLT, the balance of the 1st came ashore at Beach Blue on Zamami Shima at 9:00 am. The troopers landed against light resistance and, held up only long enough to find out that their supporting amphtracs could not negotiate the sea wall that bordered the beach, moved in quickly against some desultory mortar fire and seized Zamami town. At that point, the island’s company of soldiers and 300 Korean laborers faded back into the low hills to the south, retreating so fast that the pursuing Americans were unable to come into contact with them.

In spite of the massive offensive, the enemy was still willing to fight. After nightfall, many of the defenders attacked the 2nd BLT’s beach positions in an effort to break through their perimeter. It was a close-in duel using any weapon at hand—from pistols to swords—with the fanatical Japanese attacking again and again from different points, seeking out the Americans’ weak spot. After a storm of mortar and machine-gun fire and a loss of over 100 men, the Japanese finally stopped looking for it and fell back into the hills, leaving only seven Americans killed in the protracted fighting.

Japanese Suicide Attacks

With the multiple invasions going so smoothly, General Bruce decided to add another prize to the 77th’s collection by ordering the 307th RCT’s 2nd BLT’s reserves to load up on the LVTs returned from Aka and hit Yakabi Shima a day ahead of schedule. The strike was duly carried out that afternoon and the island taken against light resistance.

By the end of March 26, the entire western portion of the Kerama group was securely in Kiland’s hands, and the importance of its seizure had already become apparent. In their sweep of the islands, soldiers of the 77th discovered the shallow-draft “suicide boats” the Japanese intended to use to “attack … transports, loaded with essential supplies and material and personnel …[to be] carried out by concentrating maximum strength immediately upon the enemy’s landing.”

Made of plywood and powered by an 85 horsepower Chevrolet engine, the 18-foot-long boats were intended to emerge from their camouflaged hideouts carrying two depth charges each and guided by a Japanese officer right up to an unsuspecting American vessel to unload its deadly cargo. Presumably, the boat’s pilot would have a chance of getting away as the depth charges had a five-second delayed fuse.

A couple of days after the islands had been declared secure, a Japanese boat battalion commander was captured after an abortive attempt to sink an LCVA. He produced a chart showing Ushijima’s plan for the Sea Raiding Units’ area of operation, which greatly facilitated defensive measures.

Unfortunately for Ushijima, the attack against Kerama Retto ruined his plans for the suiciders, prompting General Bruce to declare that their interdiction alone made the whole operation worth it.

In addition to the suicide boats, there were suicide planes overhead as well. A total of nine kamikazes tried to breach the radar screen around Kerama on the day of the initial landings but none made it. The next day, a few more Aichi “Val” dive-bombers swooped in with one managing to slam itself into the galley of the Gilmer. Another, through a series of impressive evasive maneuvers, crashed into a 44mm stern mount on the destroyer Kimberly, killing four men.

Three Day Operation on Tokashiki

On March 27, the last islands in the Kerama group were invaded, with the garrisons on Amuro and Kuba Shima offering no resistance. At midmorning, units of the 1st BLT that had taken Geruma the day before landed at Beach Purple, just north of Hitachi Point on the west coast of Tokashiki, the largest of the Kerama islands. One sailor was killed when his LCI gunboat was hit by an enemy shore battery which was, in turn, quickly silenced as the charging troops steamrolled the light opposition gathered at the tree line.

The 2nd BLT came ashore at Aware on Beach Orange to the south in support of the 1st. Tokashiki is six miles long with its western side, called the Roadstead, offering the anchorages Kiland sought for the fleet; otherwise, its topography was much like its sister islands: rocky and scrubby with a few rough hills.

After meeting up with no more resistance than some scattered sniper fire, the two battalions linked up and began a sweep northward over the island’s goat trails. At its southern tip, the 306th’s reserve BLT, the 3rd, came ashore to secure the rear. That night, the 1st and 2nd rested just outside the town of Tokashiki in the extreme northeast, where they and Corporal Roberts later discovered the remnants of the island’s civilian inhabitants.

Earlier in the day, the 3rd BLT had kept busy on Aka when they ran into stiff resistance on one of the island’s many craggy ridges, where the Japanese defenders had holed up in prepared positions. Well supplied with mortars and machine guns, the 75 or so Japanese held the Americans at bay until air support was called in and they were bombed, strafed, and rocketed to pieces and driven from the ridge.

On Zamami, extensive patrolling unearthed small pockets of enemy troops hidden in caves. While the 3rd solved their resistance problem from the air, the 1st ended theirs on the ground with help from the unit’s amphtracks, which blasted the Japanese from their holes with some direct fire.

On the third and final day of the operation, troops on Tokashiki waited as 500 rounds of artillery pounded the already-shattered remains of Tokashiki town and then moved in. Even though there were an estimated 300 Japanese soldiers still hiding out in the hills who would not surrender until the end of the war, the island was declared secure. Later, an uneasy truce developed as the island’s enemy commander, recognizing the futility of further opposition, allowed the Americans undisturbed bathing privileges in the waters just below his gun emplacements. A hidden shore gun there was aimed straight at the scores of unsuspecting Navy ships lying in the Roadstead but was never used.

In the course of the three-day operation, the Americans lost 155 soldiers and sailors killed in 15 separate landings while the cost to the Japanese defenders was 530 killed. By March 29, the purpose for which Kerama Retto was seized in the first place was already being fulfilled. On that day, 30 planes flew in to establish antisubmarine patrols, and combat-ship refueling operations had begun in the Roadstead, a boat pool and ammunition dump set up and nets raised and tended. All was in readiness for the invasion of Okinawa two days later.

The Japanese Harassment Campaign Against Occupied Kerama Retto

In preparation for the invasion, the waters off Okinawa were to be covered by minesweepers protected by a fleet of destroyers, among them the USS Newcomb, which attracted the attention of swarms of kamikaze planes that filled the skies on the afternoon of April 6. That day, the ship was struck five times by suicidal flyers and forced out of action. Towed to an anchorage off Kerama Retto, its 75 remaining crewmen spent 10 harrowing days and nights protecting the floating hulk not only from continued kamikaze attacks, but also from the remnants of Japanese forces still holed up on the islands in the Kerama group who refused to call it quits.

“It was fairly quiet during the day, but at night it was different,” recalled Newcomb quartermaster Nate Cook. “The Japanese were using most of their air power attacking the fleet near Okinawa. But every night they would carry out small air raids over Kerama Retto. To try to protect all of the defenseless ships in the harbor, the Navy used LCVPs with smoke-making gear to create a smoke screen cover. It was eerie; we could hear the planes but not see them. We didn’t know whether they could see our masts. A couple times ships tried firing with 20mm guns through the smoke. Unfortunately the enemy could see the tracer shells and follow them down for a kamikaze crash, which they did.

“In addition to the planes, we had to worry about the Japanese still on the islands,” said Cook. “They were harassing us in several ways. The extent wasn’t clear but we knew that some had swum out at night, climbed a ship’s anchor chain, and knifed some sailors. Other ‘suicide swimmers’ had explosives attached to their torso in such a way that they couldn’t be removed without exploding.” In addition, Cook described “suicide boats” used by the enemy: fast plywood boats about 16 feet long with 4-cylinder inboard engines tried to get close enough to a ship to drop a depth charge or other explosives over the side.

Epilogue

There is an epilogue to the story of the seizure of Kerama Retto. Back on March 31, a group of LSTs approached the tiny islet of Keise Shima that lay almost within sight of the landing beaches at Okinawa. From the transports emerged the 24 155mm artillery pieces of the 420th Field Artillery Group which were floated ashore and aimed at Naha on Okinawa and the Hagushi beaches only eight miles away.

Although plans were made by Ushijima to silence the big guns with intermittent shelling and raiding parties, that action never materialized. The 420th continued to fulfill its role throughout the Okinawa campaign.

Unfortunately, the recounting of a battle, no matter how insignificant, usually fails to consider its cost to noncombatants. The tragedy of the civilian population of Kerama Retto must be treated as intrinsic to the battle itself; otherwise, war threatens to become meaningless, an end in itself.

In World War II, life sometimes seemed the cheapest of all commodities. In all of the war’s enormous cost in human suffering, the smaller tragedy of the Kerama suicides, like the small scale of the battle for the islands themselves, transcended its size to take its place as one part of the greater whole that would amount to the eventual Allied victory.

Thank you for this extremely detailed and well-written article. I believe my grandfather, a Metalsmith, was on an ARDC anchored near Kerama-Retto working to repair US ships damaged fighting the Japanese. This article was very enlightening. I appreciate reading some of the perspective of the Japanese civilians as well. Thank you.

Great information-thanks for posting. My grandfather participated in the campaign aboard the USS Forrest DMS-24, part of MinDiv 58. The ship was struck by a kamikaze on May 27th 1945 and retired to the Kerama islands for temporary repairs: 6 sailors of their crew perished and up to 20 were wounded. May God rest their souls. Ms Jen-perhaps your grandfather was one of many who worked on my granpa’s ship to repair it for its return journey to the USA in June thru July 1945? Thank you for his service. V/r JS

In October 2017 I had an article published in the now defunct “America in WWII” magazine titled “Inside the Mind of the Kamikaze!” It was taken from data collected in the Museum for Peace, the Kamikaze pilot’s museum near Kagoshima, Japan. It was really enlightening to hear what those young pilots thought on the days before they died. The suicides on the Kerama Islands bear out how the Japanese felt about their ultimate defeat.

I wasn’t aware that America in WWII had folded. Thanks for the news. They agreed to buy one of my articles several times, but then I couldn’t get them to respond to my emails. A character issue, I think. Found your website, look forward to reading your articles.

I appreciate the very detailed story about the Kerama Islands invasion. To honor my Dad, Aviation Electrician PO 2nd class Wallace K. Anderson, I wrote a story to share with my family about the kamikaze-style attack on his ship, the USS St. George a seaplane tender at Kerama Retto on May 6th, 1945 (the date is often recorded as May 5th but I believe this was due to all naval communications ignoring the international date line). The story was about an artifact he brought home from the war, an engine valve he picked up (against orders) after the attack and the plane it belonged to – the Japanese Army aircraft Ki-61 Hein.

Greatly appreciate this article. My father was on board the SS Hobbs Victory as a naval armed guard gunner on April 6. They were unloading mortar ammo for the Marine landings.The Hobbs and the Logan Victory were both sunk that day by Kamikaze raids. I understand that tactics of the landings had to be altered because of the loses of these ships and supplies. I only learned of these events just before his passing in 2007. He never spoke of it growing up. Still filling in

many details of that day. This helps much. Thank you..Chuck Walker. USN Vietnam ‘69-‘70

Side note: Okinawans are an ethnic sub group of Japanese and the relationship since the end of WW II has not always been smooth. Okinawans believe that the main island Japanese used Okinawans as cannon fodder to slow the American forces during the final months of the war and as a result civilian casualties were quite high. In return, the main island Japanese do not always see Okinawans as fully Japanese, feelings which are often mutual.

Another fine artical

You have obviously done a lot of research to put together this article. I lived on Zamami-son, Kerama-retto, Okinawa-ken, Japan, for 3 years 2000-2003 and interviewed a number of local islander survivors and a Japanese ex-soldier about the island’s WWII history. I also corresponded with the family of a deceased US soldier with the intention of uncovering an accurate record of WWII events on Zamami, Aka and Geruma. I handed over my research to the Zamami Village Office in 2019. Since then, Zamami, with the efforts of local CIR Jaime Cerna, has created this wonderful website: https://zamami-peace.net and made additional efforts to commemorate sites of historical significance on the islands. Please take a look.

My dad was there on the Shannon, DM-25.

Your work is excellent, but I am unable to confirm the dates of one event that is evading me. My father who was on the LCS(L)(3)-17 said that after the landing they sailed to Naha and then rendezvoused at Kerama Retto, where they were attacked by Kamikaze aircraft; but I have been unable to place a date on this attack. He said that this action, during which fifty-three Kamikazes were shot down, was the most memorable part of his naval career. He himself downed three Kamikazes in this attack. As the landing was on April 1, this could have been the attack associated with the USS Newcomb on April 6; but your presentation implies that the latter was during preparation for the invasion, not after the landing, which leaves me a bit uncertain. Are you able to direct me to a source that may tie down the date of the attack associated with the LCS(L)(3)-17?

My father (William C Bolte) was in air-sea rescue and his plane arrived at the islands a day early. Here is his brief recounting of his event

After seeing the large number of ships, our pilot (Lieut JG, Maynard Kouns) told us that we were to land (on water) at a place called Keramma Rhetto. (you should forgive the spelling), and that someone had provided us with the intelligence that the Island didn’t have any shanty-eyed troops. This information dated about 1933 we really didn’t know anything and for all the information we had we could expect to be fired on as soon as we tried to land. We all knew that Military Intelligence is an oxymoron. So, I along with several others was expecting to hear machine gun fire as soon as we leveled off for landing. The bay where we were instructed to land is within easy .50 caliber machine gun range to where we touched down. It would have been like shooting ducks.

Next we found spot to anchor a buoy and we did just that. The surprise came after dark when some of our picket boats discovered that our hosts were planning to send swimmers out to place explosives against the side of the aircraft. Everyone was trigger happy. I, a “Medic” was forbidden by the Geneva Convention from carrying a weapon. The Japanese had never signed the document and felt free to maim, kill or mutilate their sworn enemies: us. Consequently I was armed with a Thomson sub-machine gun, a thirty eight special revolver. and two percussion grenades. Each enlisted member of the crew had to stand watch for couple of hours from atop the wing to spot any attempt on our wellbeing.. I was the last member to receive a weapon so I got the Thompson which is quite heavy compared to the .30 caliber carbines that everyone else was allotted. I never fired the gun except for one occasion, just before dusk, when I saw someone on the shore and opened fire. It was stretching the range of the .45 caliber weapon so it is doubtful that I did any more than scare the getas off of the intended victim.

My father Lt. Comdr. Roger L. Alaux was killed by a kamikaze attack on 1 May 1945. He was the Fleet Staff Officer responsible for the net defenses and assigned to the cruiser USS Terror. The Terror lay at anchor in Kerala Retto where it was attacked. 171 casualties: 41 dead 7 missing and 123 wounded.