By Cowan Brew

An angry gloom hung like dust over the 6,000 Confederate cavalrymen trooping up the York Turnpike in the early dawn of July 3, 1863. After eight long and largely unproductive days in the saddle, the horsemen were setting out on a last-ditch effort to disrupt and disarrange the rear of the Union Army confronting General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at the tiny crossroads town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. A blood-red sun—always an evil portent to experienced campaigners—shone directly into the men’s eyes, and the damp summer heat was already soaking through their short, gray uniform jackets. It was clear to everyone that the day would only get hotter, literally and figuratively, before it was over.

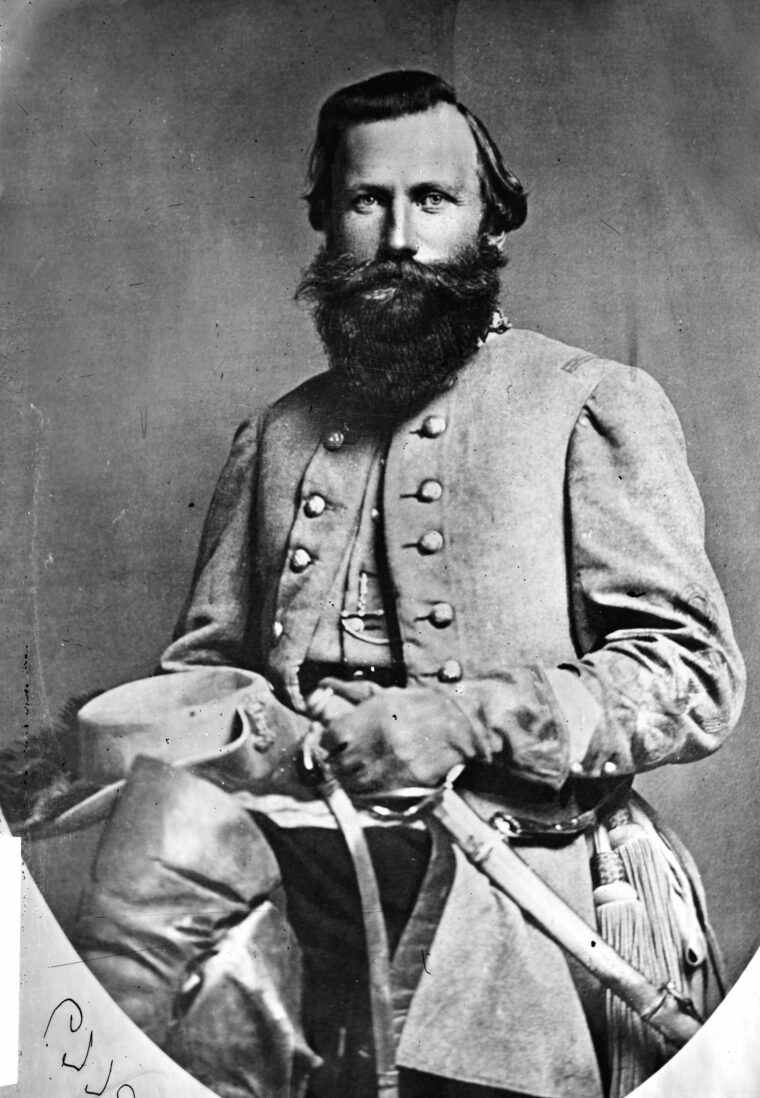

No one was angrier or gloomier than the troopers’ famous commander, James Ewell Brown Stuart. The day before, the flame-bearded young general had sauntered into Lee’s headquarters tent on Seminary Ridge at Gettysburg, expecting the usual courtly greeting from his old friend and mentor. Instead, an obviously angry Lee, worn and distracted by two days of unparalleled savagery with nothing to show for it but a bloody stalemate, glanced sharply at Stuart with cold, dark eyes. “General Stuart, where have you been?” he asked brusquely. When Stuart attempted to describe his recent whereabouts, Lee cut him off with a withering look. “I have not heard a word from you for days,” he seethed, “and you are the eyes and ears of my army.” Embarrassed observers said later that Stuart looked as though he had been slapped in the face. He accepted the rebuke with a lowered head.

The fact that both men shared the blame for Stuart’s untoward absence made the meeting no less uncomfortable. Lee, as was his increasing habit, had given Stuart a vague, all-encompassing order to “pass around” the Union Army massed below the Potomac River in northeastern Virginia and “collect all the supplies you can for the use of the army.” At the same time, he had directed his 30-year-old cavalry commander to screen Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s II Corps as it advanced into Maryland and to break off his expedition if he ran into any “hindrance” from the Federals. Having made a household name for himself a year earlier by riding completely around a similar Union Army under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan in Virginia, Stuart intended to duplicate that noteworthy raid. He and his men never considered Union soldiers, whether cavalry or infantry, a particular hindrance to their plans. The still-painful memory of the drawn cavalry battle at Brandy Station, Virginia, three weeks earlier gave added motivation to the southern riders.

A Second Invasion Across the Potomac

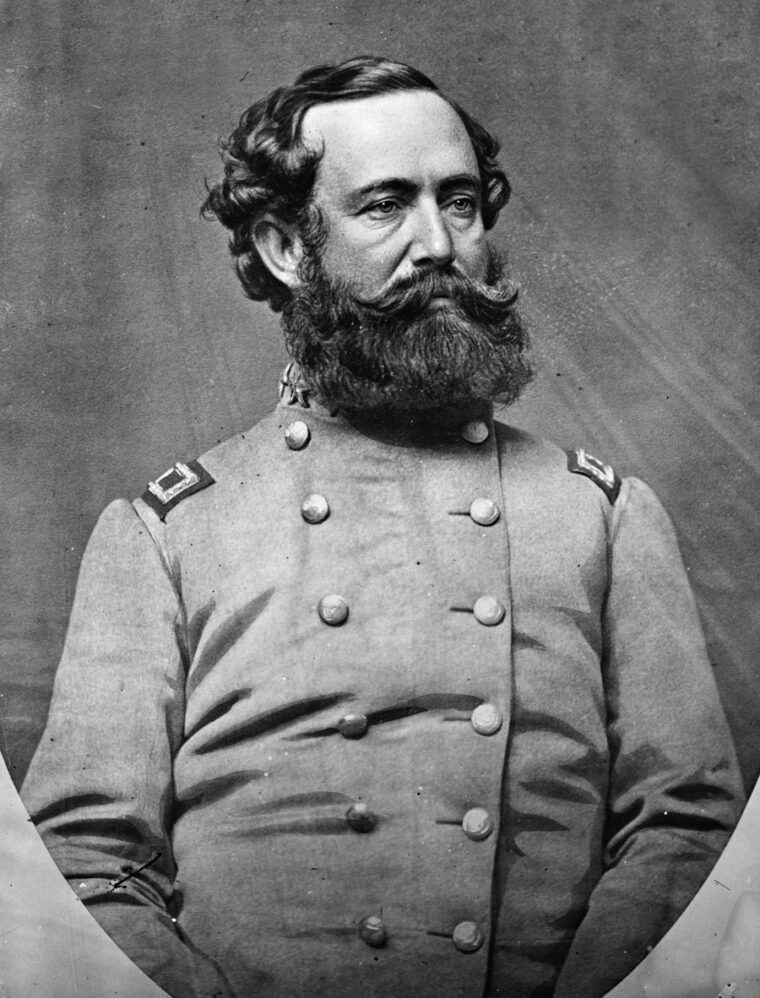

Beginning on June 25, Stuart’s horsemen rode east from Salem, Virginia, intending to turn north and link up with Ewell around York, Pennsylvania. In the meantime, Lee’s massive army began moving northward as well, mounting its second invasion of enemy soil in nine months. The first invasion had ended badly at the Battle of Antietam; Lee intended the second one to go much better. For that to happen, he needed accurate information from his cavalry arm, but for once he was let down in his expectations. The brigadier generals Stuart left behind to guard Lee’s flanks, Beverly Robertson and William “Grumble” Jones, were not up to the task. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, commanding Lee’s I Corps, complained later with some justice that Stuart had left them his least favorite officers. Stuart could scarcely argue with that assessment. He considered Robertson “by far the most troublesome man I had to deal with,” in no small part because Robertson had been a former suitor of Stuart’s wife, Flora, and a protégé of his much-despised father-in-law, Union Brig. Gen. Phillip S. George Cooke, in the Old Army. The irascible Jones had more than lived up to his nickname of “Grumble” on numerous occasions, and, although he was a better general than Robertson, he was outranked by the other officer. In the confused command situation, each failed to notify Lee that the Union forces had broken camp and set out after him. As long as Stuart was out of touch, Lee was effectively flying blind—hardly the best way to begin the most crucial campaign of the war.

Meanwhile, free of his unlikable subordinates, Stuart galloped east with his battle-tested troopers. Stuart sent his most reliable scout, John Singleton Mosby, ahead to map out the best route across Maryland into Pennsylvania. Mosby, who would later win fame as the “Gray Ghost,” leading the 43rd Battalion of Virginia cavalry on numerous independent raids in northern Virginia, reported back that Stuart could pass easily around the widely dispersed Union Army in western Maryland. It was a dangerously upbeat assessment, and it cost Stuart several hours when he discovered that the Federals had already moved out and occupied the road at Haymarket, Virginia, on which Stuart had expected to move. Had Stuart returned to Lee then, or at any rate reported the enemy movement, it might have changed the entire course of the campaign. Instead, Stuart was content to graze his horses in a field nearby while the unsuspecting Federals passed unimpeded.

Stuart’s Needless Delays

Crossing the Potomac at Rowser’s Ford, Stuart tore up a portion of the C&O Canal and swooped down on 125 enemy supply wagons at Rockville, Maryland, driving the fleeing teamsters all the way to the outskirts of the nation’s capital at Washington. Instead of burning the wagons and continuing with all haste to join Ewell’s vanguard, Stuart wrongly decided to hold onto the bulky wagons and their treasure trove of hams, sugar, and whiskey. This was the very definition of a hindrance, but Stuart blithely ignored Lee’s injunction and continued northeastward—farther and farther away from Lee’s army. Two days later, Lee was still telling Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble, “I have not yet heard that the enemy have crossed the Potomac, and am waiting to hear from General Stuart.” He would continue waiting for several days.

While their infantry comrades stumbled blindly into a major confrontation with the Union Army of Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade south of Gettysburg, Stuart’s horsemen wasted precious hours tearing up a six-mile stretch of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and paroling the 400 prisoners taken at Rockville. The hungry and thirsty mules pulling the captured wagons became increasingly unmanageable, a “source of unmitigated annoyance,” according to Stuart aide Lieutenant William Blackford. Repeated clashes with screening Union cavalry further impeded Stuart’s progress. In one close-run encounter near Hanover, Pennsylvania, Stuart had to leap his horse, Virginia, across a 15-foot-deep gully to avoid capture or death. Meanwhile, an anxious Lee paced about his tent, asking new arrivals: “Have you heard anything about my cavalry? Any news to give me about General Stuart?” For several days, the answer to both those questions was a dispiriting “no.”

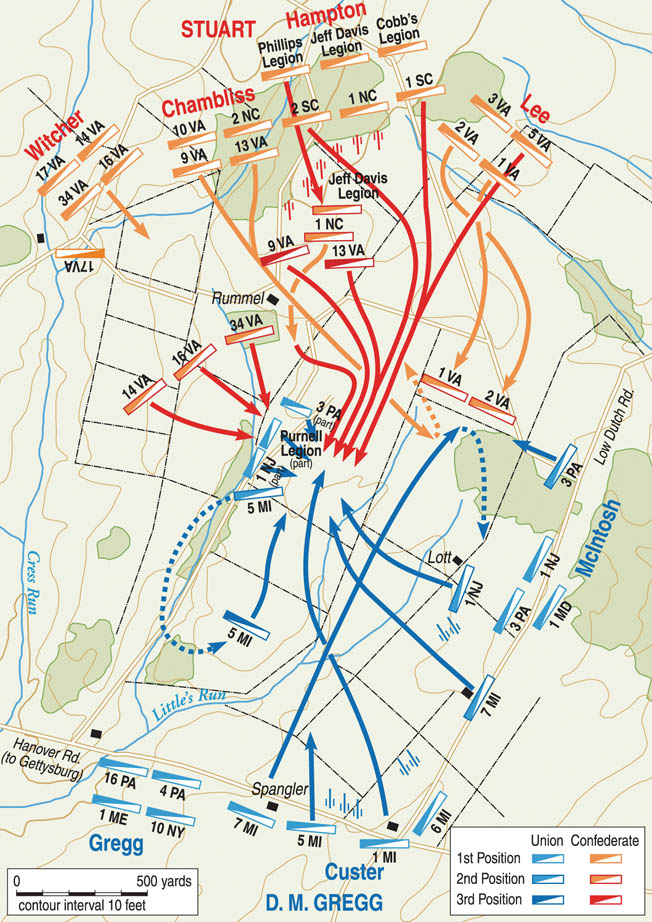

At last, on the afternoon of July 2, Stuart’s column finally reached the outskirts of Gettysburg. Locating Lee’s headquarters on Seminary Ridge, the weary cavalryman entered and saluted his commander. “Well, General Stuart, you are here at last,” said Lee, before delivering his terse, devastating rebuke. With Lee’s clipped words ringing in his ears, Stuart headed out again the next morning, marching northeast, then south, across the open countryside between the Hanover Road and the Baltimore Pike. Colonel Milton Ferguson’s brigade led the advance. At Cress’s Ridge, a long, low hill overlooking the farmland south of the York Turnpike, Stuart stopped to take stock of the situation. After scanning the surrounding countryside, he sent Lt. Col. Andrew Witcher’s 34th Battalion forward to seize a nearby farm and fence line owned by local farmer John Rummel, half a mile to the east.

“The Boy General of the Golden Locks”

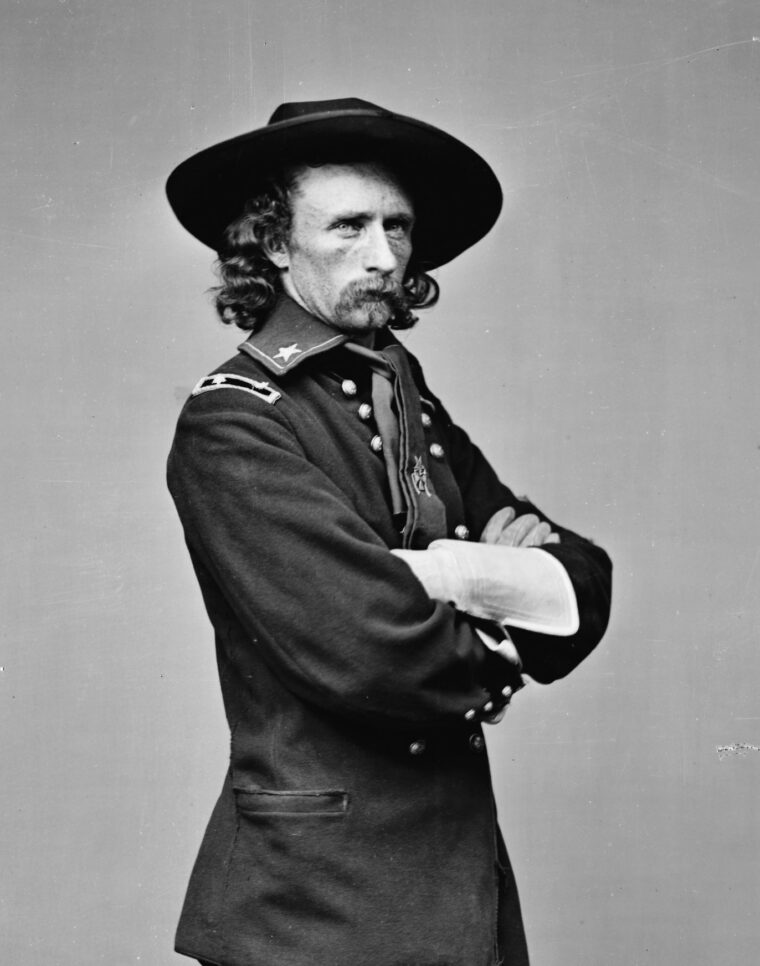

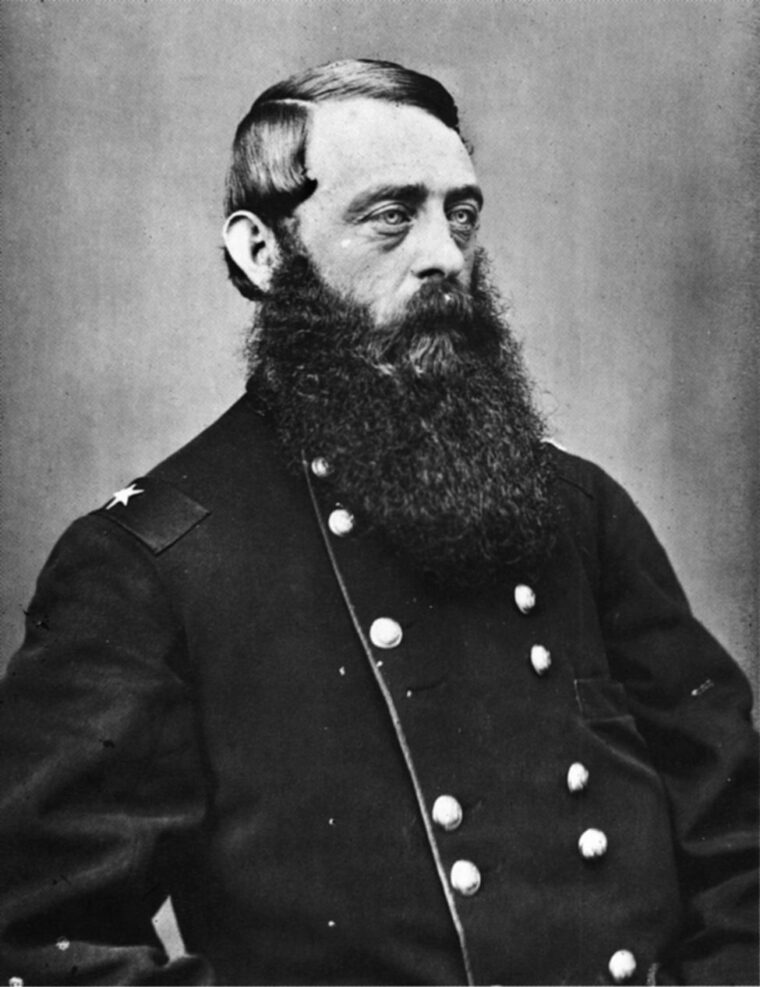

While Stuart’s skirmishers were creeping forward, his blue-clad counterparts in the Federal cavalry had not been inactive. Brig. Gen. David McMurtrie Gregg, a native Pennsylvanian commanding the 2nd Division, moved swiftly to block the dangerously open terrain north of the Baltimore Pike, asking cavalry commander Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton for an additional brigade to help safeguard the position. Pleasonton agreed, sending Gregg a grass-green young brigadier named George Armstrong Custer from the 3rd Division to assist in the defense.

Custer, the goat of the 1861 graduating class at West Point, had worn his general’s stars only for a few days, but already he had made a name for himself among Union horsemen. One of three “boy generals” promoted by Pleasonton in early June (Elon Farnsworth and Wesley Merritt were the other two) to give more youthful élan to the cavalry, the 24-year-old Custer was a natural-born self-dramatist. Wearing a gaudy nonregulation uniform that he had designed himself of black velvet trimmed with interlocking gold lace on the sleeves, a wide-collared navy blue shirt, and a bright red necktie, Custer ensured that he would always be the most colorful officer on any battlefield. Long blond hair falling nearly to his shoulders completed the corsair look. His new command greeted his arrival with veteran humor. “Who is the child?” they joked. “Where is his nurse?” After helping beat back Stuart’s advance at Hanover, Custer won their grudging respect. Now they called him “the Boy General of the Golden Locks.”

Gregg placed Custer’s division, composed of all Michigan troops from the 1st, 5th, 6th, and 7th Regiments, at the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch roads. Custer positioned the 5th and 7th Regiments, facing north, in an open field where the two roads crossed; the 6th was farther west along Little’s Run, a shallow stream flowing south from the farm. Dismounted scouts reached the base of Cress’s Ridge and dashed back to report that two brigades of Rebel cavalry, supported by artillery, were moving through the trees on the high ground, little more than a mile away. Custer immediately wheeled about six mounted artillery pieces served by his old West Point friend, Lieutenant Alexander Pennington. Four quick rounds from a Confederate Parrott rifle ripped through the air. Union Colonel John McIntosh, commanding Gregg’s 1st Brigade, rode up to Custer and asked for a summary report of the enemy’s location. “I think you will find the woods out there full of them,” Custer replied with a smirk, pointing toward Cress’s Ridge. McIntosh dismounted skirmishers of his own from the 3rd Pennsylvania, 1st New Jersey, and Purnell (Maryland) Legion.

Custer and McIntosh were in the process of organizing a defensive line when a literally earth-shaking blast began two miles away. Seeking to soften up the Union center preparatory to the desperate frontal assault that would become known as Pickett’s Charge, massed Confederate cannons had just unleashed the largest display of concentrated artillery fire ever heard on the North American continent. The ground shook beneath the Union cavalrymen and smoke rolled across the valley beyond. It appeared as though the very woods around them had been set on fire. The world seemed to be coming to an end.

“Come On, You Wolverines!”

Whether by coincidence, design, or sheer inspiration, Stuart launched his own attack shortly after the ear-splitting cannonade began. His plan, he explained later in an after-battle report, was to keep the enemy pinned down in the front by sharpshooting skirmishers while sending his mounted forces around to attack the enemy left. The strategy began unraveling almost as soon as it began. By an oversight on the part of their acting brigade commander (Brig. Gen. Albert Gallatin Jenkins, the regular commander, had been wounded by a sniper the day before), Witcher’s men had advanced with only 10 rounds of ammunition apiece. They quickly expended all their rounds in a nasty firefight with members of the 5th Michigan and 1st New Jersey, and pulled back to the Rummel farm to await reinforcements.

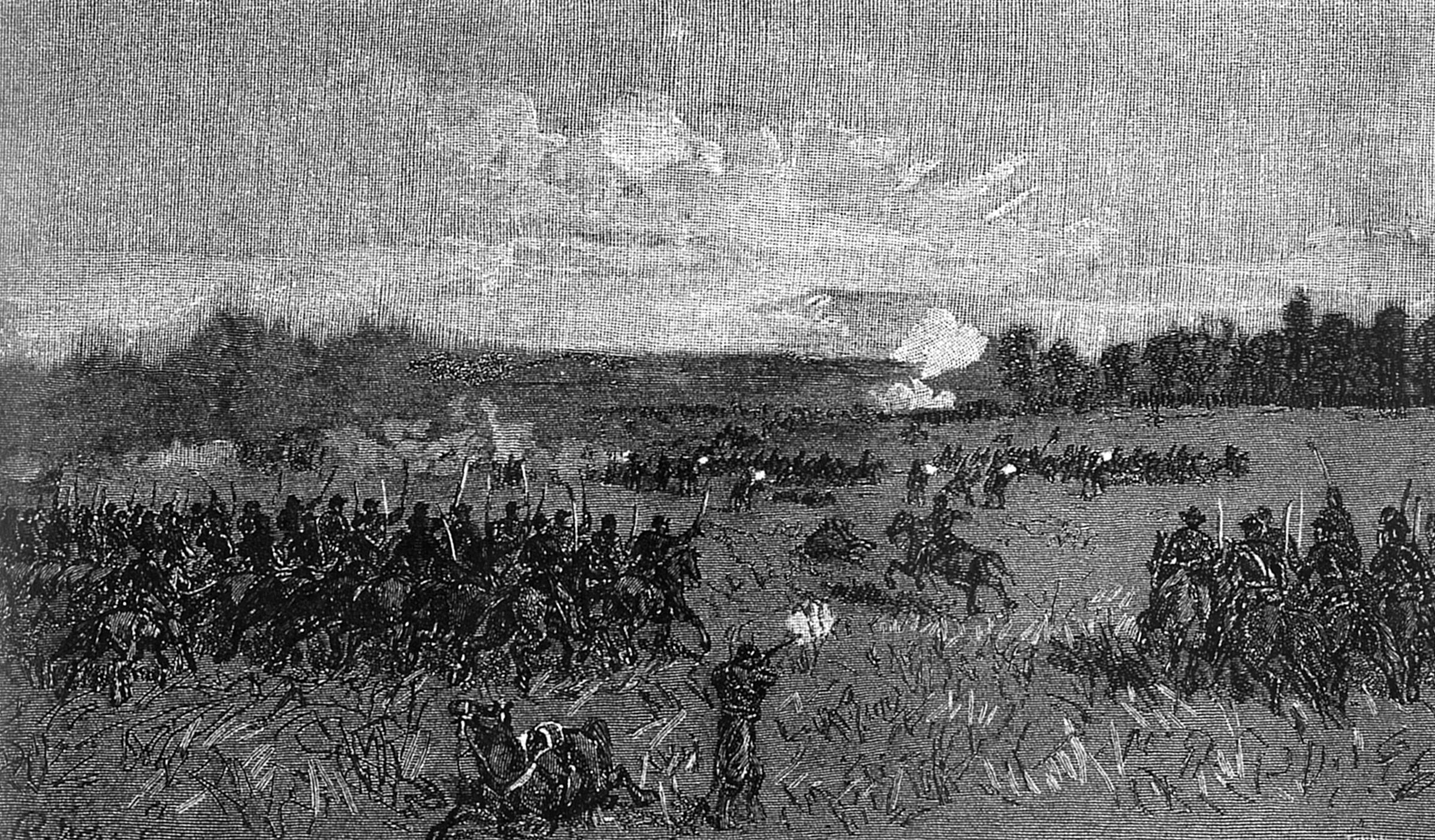

Stuart had been hoping to keep his mounted brigades hidden while they formed ranks and drove into the Union flank, but the battle seemed to be quickly getting away from him. Shoring up Witcher’s skirmish line, he sent Brig. Gens. Wade Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee into the fray. The southern horsemen, in columns of four, galloped across the open field below Rummel’s farm and crashed into Custer’s right flank. Peppered by fire from Witcher’s newly replenished battalion, the 5th Michigan fell back in disarray toward their artillery. Gregg, watching the battle unfold, ordered the 7th Michigan, which had been standing in reserve, to mount a counterattack. Custer, reacting swiftly for a neophyte brigade commander, drew his sword, reared up in his saddle, and cried, “Come on, you Wolverines!”

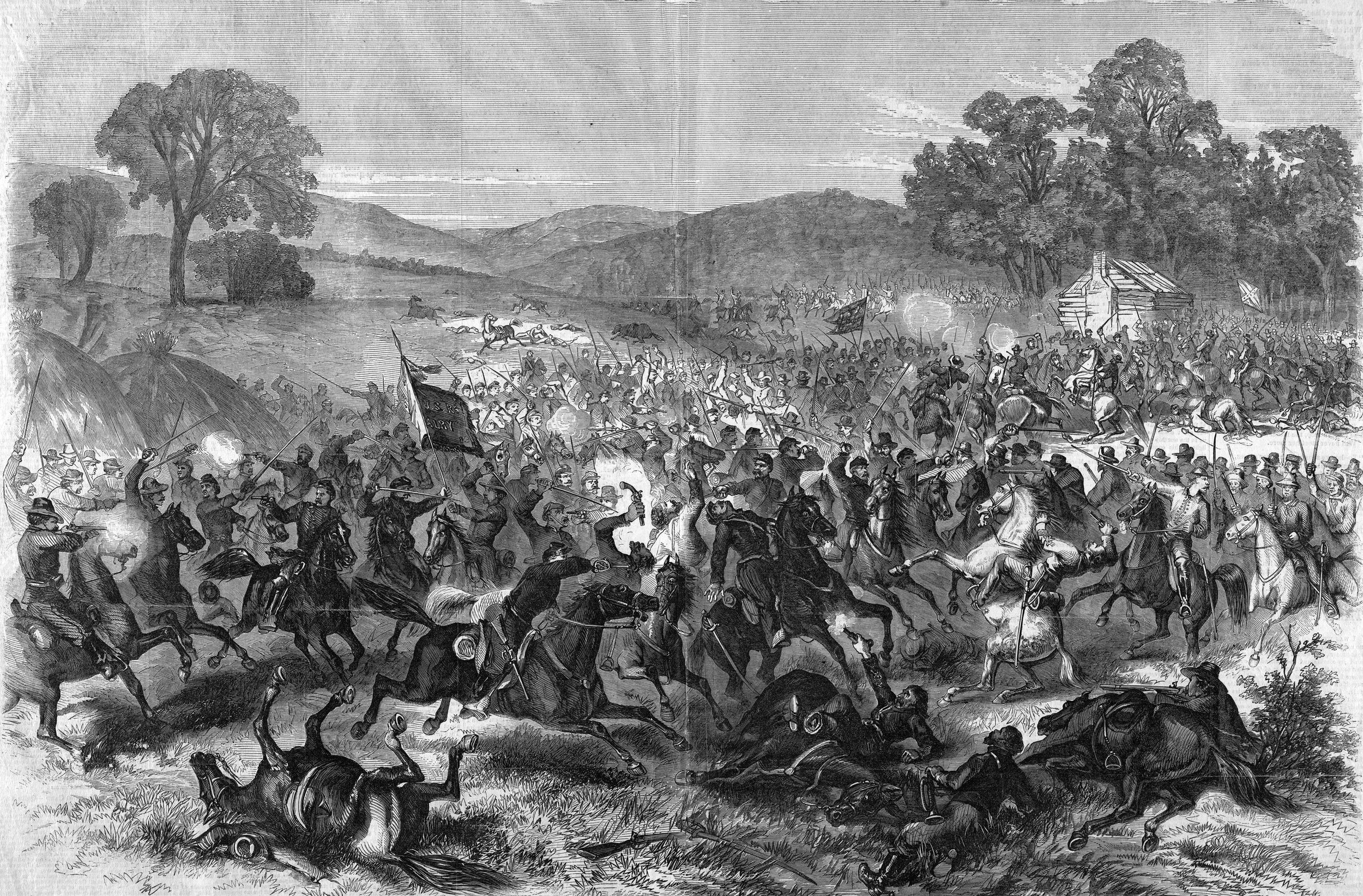

Spearheaded by 21-year-old regimental commander Colonel William D. Mann, the 7th Michigan troops directed a relentless pistol fire at the Confederates, who had taken cover behind a low post-and-rail fence. The retreating members of the 5th Michigan stopped dead in their tracks to watch the attack. The two sides came together with a sound like falling timber. “So violent was the collision,” reported Captain William E. Miller of the 3rd Pennsylvania, “that many horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them.” Miller himself reported receiving “a slight scratch”—actually a bullet through his arm. The fence broke up the charging Union column “into jelly, mixing us up like a mass of pulp.” The two sides flailed at each other with sabers and blasted away with pistols and carbines. It was literally hand-to-hand combat. When farmer Rummel returned to his home after the battle, he found two dead men lying in the lane amid 30 dead horses, their stiffened fingers still embedded in each other’s lifeless throats.

Disastrous Charge of the 7th Michigan

Thinking quickly, some of the Michiganders leaped off their horses and leveled a piece of the fence, allowing the rest of their mounted comrades to pour through. “Kill all you can and do your best for each other,” Mann urged. Custer led the 7th Michigan forward, aiming at a Rebel battery posted just below the Rummel farm. “At them we went, every man for himself,” boasted coincidentally named Captain George Armstrong. The 7th Michigan, from the Grand Rapids area, was the least experienced regiment in Custer’s brigade; most of the men had seen only patrol duty since arriving at the front two months earlier. They soon got the worst of it with the more battle-savvy Confederates, who clung to the necks of their horses like Apache Indians and fired at them from below with their pistols. Everyone was screaming like banshees. Sabers thudded into skulls with the sickening sound of a stick bursting a ripe watermelon. The fight, “desperate but unequal,” according to Mann, lasted for 10 minutes—it seemed longer to those in the midst of it—with the 7th Michigan losing more than 100 men in the fray. Private Allan Price of the 6th Michigan, observing the contest, recalled later: “The 7th Michigan made a charge and got all cut to pieces. It was the first charge they ever made and it was awful work.”

Custer disagreed. “I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry,” he wrote later. Those who had been in the charge agreed wholeheartedly with that assessment. “This is the most furious dragoon fight I ever saw or engaged in,” Dexter M. Macomber of the 6th Michigan noted in his diary. A comrade in the same unit, Andrew Newton Buck, called it “the hardest battle of the war. Cavalry never did such fighting before in America.” Edward Corselius of the 5th Michigan combined the sentiments. “Such fighting I never saw before,” he wrote to his mother. “It is an honor to belong to Mich[igan] Cavalry.”

At the time, carried away by excitement, Custer dashed forward into the open field beyond the fence, only to look back in horror and see the rest of the regiment still bogged down behind him. Hastily ordering the bugler to sound retreat, Custer had his men wheel about just as two fresh Confederate regiments, the 1st North Carolina and the Jeff Davis Legion, rode down to meet them. Fitzhugh Lee’s vaunted 1st Virginia joined the charge. Custer was suddenly in danger of being cut off. “We must get back behind the guns,” he rather needlessly advised Captain Armstrong. The two rode for their lives. Colonel McIntosh arrived on the scene, exhorting the retreating soldiers to hold their positions. “For God’s sake, men, if you are ever going to stand, stand now, for you are on your own free soil!” he shouted. Colonel Russell A. Alger, 5th Michigan commander and later secretary of war under President William McKinley, organized a volley into the enemy’s onrushing flank. The southerners recoiled and withdrew to the comparative safety of Cress’s Ridge.

“Charge Them, My Brave Boys, Charge Them!”

Watching from the crest, Stuart worried that his men’s inherent aggressiveness had carried them too far. “The charge being very much prolonged, their horses, already jaded by hard marching, failed under it,” he reported later. “Their movement was too rapid to be stopped by couriers, and the enemy perceiving it, were turning upon them with fresh horses.” Brigade commander Wade Hampton of South Carolina shared Stuart’s concern. Grabbing his personal colors, Hampton spurred his enormous war horse, Butler, down the ridge toward his imperiled troopers, shouting for them to fall back. Major T.J. Barker, Hampton’s adjutant, saw the colors waving through the smoke and mistakenly believed that he had signaled an all-out advance. Barker gathered up the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Regiments, along with Phillips Legion, and followed Hampton into the maelstrom. Looking back over his shoulder, Hampton was shocked to see the entire brigade dashing after him. Nevertheless, his own blood was up. “Charge them, my brave boys, charge them!” he cried.

The Union troopers watched the advance in open-mouthed wonder. Captain Miller of the 3rd Pennsylvania recorded the scene for posterity in awestruck terms: “A grander spectacle than their advances has rarely been beheld,” he wrote. “They marched with well-aligned fronts and steady reins. Their polished saber-blades dazzled in the sun. All eyes turned upon them. Shell and shrapnel met the dancing Confederates and tore through their ranks. Closing the gaps as though nothing had happened, on they came. As they drew nearer, canister was substituted by our artillerymen for shell, and horse after horse staggered and fell. Still they came on.” Southern officers sought to maintain order amid the chaos. “Keep to your sabers, men, keep to your sabers,” they urged.

The Union gunners opened on the approaching horsemen, trying to slow them down. Horses and men fell, head over heels, but the mass of Confederate riders kept advancing. There were simply too many of them to stop. The artillerymen rammed double shots of canister—one-inch steel balls packed tightly in cylinders—into their guns and fired point-blank at their attackers. Custer’s old West Point comrade Alexander Pennington directed a “dreadful havoc” of shells into the Confederate ranks. “On came the Rebel cavalry, yelling like demons, right toward the battery we were supporting, sweeping everything before them,” Union cavalryman George Kidd remembered.

Wade Hampton’s Brush With Death

Gregg, taking personal charge of the battle, ordered a countercharge. Custer was quick to oblige. Riding up to his only uncommitted regiment, the 1st Michigan, he approached its commander, Colonel Charles H. Town. Speaking with elaborate formality, perhaps as a way of keeping his own nerves steady, Custer said, “Colonel Town, I shall have to ask you to charge, and I want to go in with you.” Town, who was dying of tuberculosis, had to be strapped into his saddle before the battle. Some said he was courting a soldier’s death on the battlefield to avoid wasting away in a consumptive’s bed. Whatever his motivation, he obeyed immediately and got the regiment moving. It was now 3 pm.

Private Cassius Norton of Company M described the ensuing charge. “We went out with a trot in columns of squadrons,” he recalled. “At the time the command ‘charge’ was given we bounded from a trot into a gallop, the hill and its sides towards us crowded with screaming advancing rebels headed for us, 3 or 4 columns of them, while beyond our right was the shattered 7th rallying as best they could here and there.” “Come on, you Wolverines!” Custer shouted again, vaulting from his stumbling charger, Roanoke, onto a nearby riderless horse and swiping at an oncoming Rebel with his saber.

Where a narrow lane crossed the farmland, the fighting peaked in intensity. Hampton, a strapping 6 feet, 2 inches tall, towered over the battlefield. Several Union troopers, attracted by Hampton’s massive figure and the glinting gold stars on his collar, raced to surround him. Hampton unhorsed one attacker with his sword, unloading his revolver at the others. Hemmed in against a fence, the general faced sure capture or death. Two Mississippians from the Jeff Davis Legion rode to his rescue but were sabered off their horses by the milling Federals. Other swords sliced open Hampton’s forehead and ripped through his uniform. With all his fast-ebbing strength, Hampton raised his heavy sword and brought it down on an attacker’s head, splitting him open from crown to chin. Literally soaked in blood, the general reeled in the saddle while wary Federal troopers circled him, looking for an opening to finish him off.

At the critical moment, Sergeant Nat Price of the 1st North Carolina galloped into the melee, shooting down one Yank who was aiming a killing blow at Hampton’s head. Other Confederates dashed to the general’s aid as well. “General, they are too many for us!” Price cried. “For God’s sake, leap your horse over the fence; I’ll die before they have you!” Although stunned by the near-fatal blows, Hampton leaped the fence to safety. In midair, a piece of shrapnel smashed into his side, almost unhorsing him, but the lifelong horseman kept to the saddle and dashed up Cress’s Ridge to safety, relinquishing command to Colonel Laurence Baker of the 1st North Carolina as he was helped from the saddle. It would be several months before Hampton could return to active service.

Captaim Miller’s Medal of Honor

Intense personal combat was taking place all over the battlefield. Captain Walter Newhall of the 3rd Pennsylvania spurred his mount toward a flag-bearer from Hampton’s brigade. Reaching out to seize the standard, Newhall was smashed in the face by the flagstaff, opening a hideous wound in his jaw. (He would survive the war and become a longtime aide to General Phil Sheridan in the Indian wars out West.) Of the 22 men Newhall led onto the field that day, 18 were killed or wounded.

Small groups of Federals continued pecking away at the Rebel flanks. One battalion, led by Captain Miller of the 3rd Pennsylvania, managed to penetrate the gray ranks and get into their rear, sowing more confusion in an already out-of-control situation. With the main thrust of the attack now blunted and more and more Union riders appearing on their flanks and in their rear, the Confederates broke off the fight and galloped back toward Cress’s Ridge. Miller’s men pursued them as far as Rummel’s farm, where one Union trooper had the top of his scalp sliced off as quickly and easily by a southern swordsman as if he had been scalped by an Indian, leaving him, said Miller, “as neatly tonsured as a priest.” For his leadership, Miller would later be awarded the Medal of Honor—making him the only Union soldier to win the nation’s highest honor that day at Gettysburg.

Was Stuart’s Tardiness to Blame?

Stuart withdrew his forces from the ridge at sunset and reformed along the York Turnpike. Although inflicting 254 casualties—some 219 in Custer’s brigade alone—to 181 of their own, Stuart’s riders had failed to reach the Union rear. It would not have made any difference if they had; Pickett’s Charge had failed and the entire Confederate Army was in retreat. The Battle of Gettysburg was lost. Almost immediately, a second battle began—this time in the court of public opinion. Stuart was pilloried unmercifully for his absence prior to the start of the battle, and many southerners (including, by implication, Robert E. Lee) blamed Stuart for the disastrous defeat. Said a well-connected journalist in the Mobile Daily Advertiser: “His [Stuart’s] vanity seems to have controlled his actions, and the cavalry was used frequently to gratify his personal pride and to the detriment of the service. At the Battle of Gettysburg, he was not to be found, and Gen. Lee could not get enough cavalry together to carry out his plans.”

Stuart’s supporters leaped to his defense. “It was not the want of cavalry that General Lee bewailed, for he had enough of it had it been properly used,” wrote Stuart’s adjutant, Major Henry McClellan. “It was the absence of Stuart himself that he felt so keenly.” John S. Mosby, the scout whose initially misleading report had contributed much to Stuart’s decision to continue his raid, blamed Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson for not moving quickly enough to support Lee’s infantry. “The only thing I blame Stuart for was not having him [Robertson] shot,” wrote Mosby. The debate raged on for years after the war, and most historians have apportioned some of the blame to Stuart for the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, while conceding that he had been given just enough autonomy by Lee to absolve him from any official misconduct. Stuart aide William Blackford probably best summed up the cavalry battle at Rummel’s farm. “It was about as bloody and hot an affair as any we had yet encountered,” Blackford wrote. “The cavalry of the enemy were steadily improving, and it was all we could do sometimes to manage them.” In the rolling farmland east of Gettysburg, on the third day of the largest battle of the Civil War, they had scarcely managed them at all.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments