By William Stroock

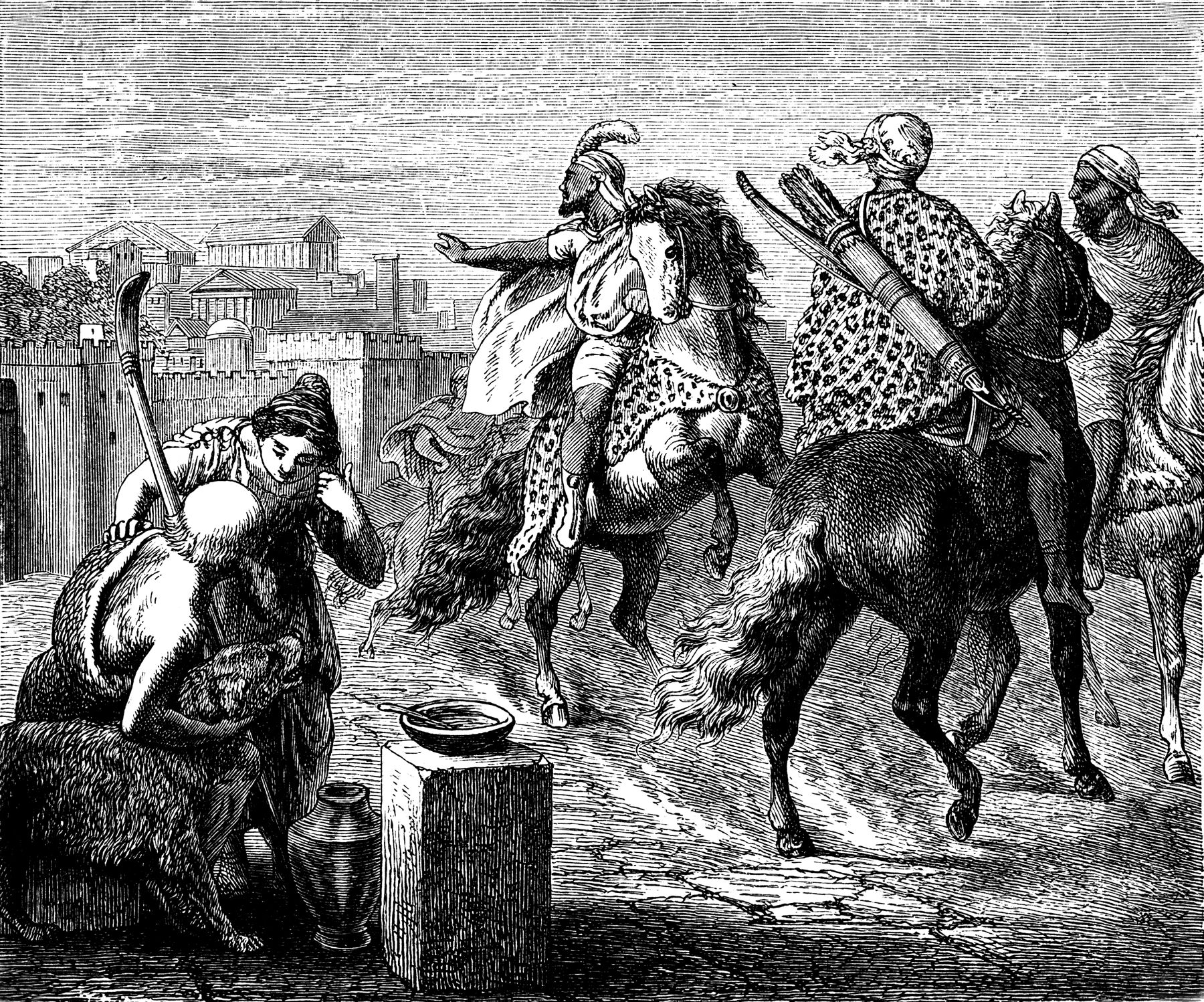

Jugurtha, king of the desert nation of Numidia, was a long-time antagonist of Republican Rome. Over more than a decade of war, he was a bold and cunning battlefield commander who used swiftness and determination to make fools of Roman consuls, even as the Romans were systematically conquering his country. Jugurtha came to his role naturally. His father, King Micipsa, divided his kingdom (much of northern Algeria today) between his three sons, Jugurtha, Hiempsal, and Adherbal, none of whom was happy with the arrangement. The most able of the three half-brothers was Jugurtha, a good-looking, intelligent, active man who eschewed the trappings of luxury for a rugged lifestyle, making a name for himself as an athlete and big game hunter.

Jugurtha Sparks War With Rome

Fearing his son’s fame, Micipsa gave Jugurtha command of the Numidian contingent sent to aid Rome in the siege of Spanish Numantia (134-133 bc), in the hopes that he would get killed. Instead, Jugurtha excelled at the art of war, leading his men ably in battle and becoming popular with the Roman troops. He greatly impressed the Roman commander, Scipio Aemilianus, who used him for difficult tasks and treated him as a friend.

At a meeting a few days after Micipsa’s death in 118 bc, Jugurtha had Hiempsal assassinated and then systematically massacred Adherbal’s allies in the various Numidian towns, throwing some of his victims to wolves and lions and crucifying others. Adherbal, described by Roman historian Sallust as quiet, peaceful, and meek, was no match for the ruthless Jugurtha, who quickly routed his surviving brother’s army. Adherbal fled to Rome and begged the Senate for help.

Fearing Rome’s reaction to his bloody coup, Jugurtha dispatched envoys of his own to argue his case and bribe the Senate. After furious debate, the Senate, encouraged by Jugurtha’s bribes, established a 10-man commission to divide Numidia between the two rivals. Jugurtha promptly bribed the commissioners, who consequently awarded him the more fertile western part of the country, while Adherbal got the east and north.

Jugurtha accepted the decision and retired to his new kingdom, where he prepared for renewed war against his brother. In the spring of 112 bc, Jugurtha led a raiding party into Adherbal’s kingdom. Once again Adherbal appealed to Rome for help. Sensing Adherbal’s weakness, Jugurtha launched an all-out invasion. Adherbal raised an army and met Jugurtha outside Cirta, the capital of Adherbal’s kingdom. Jugurtha did not wait for formal battle. Instead, he simply stormed Adherbal’s position, routing his brother’s troops and moving to occupy Cirta. Only the swift intervention of Italian merchants, who slammed shut the gates and manned the battlements, kept the city out of his hands. Jugurtha promised clemency, then duplicitously massacred the Italians (and Adherbal) once they opened the gates. An outraged Roman Senate voted to go to war against the Numidian betrayer.

Defeating the Roman Invasions

The consulship for Africa went to Lucius Calpurnicus Bestia, who raised an army of two Roman and two allied legions and surrounded himself with trusted political allies. While the Roman army was well organized and disciplined, it was ill suited to Jugurtha’s way of war, which featured light cavalry and infantry striking quickly and avoiding pitched battle. Jugurtha had another advantage—he was fighting in friendly territory, with a helpful populace, over ground he knew like the back of his hand. Against repeated Roman forays, Jugurtha was able to fall back to mountain or desert fortresses virtually inaccessible to the large, lumbering Roman army.

As the Roman army advanced into Numidia, the wily Jugurtha retreated and sought other ways to defeat the Romans. Rather than fight, he negotiated peace in return for a quantity of silver, horses, cattle, and elephants. Bestia returned to Rome with the treaty, which proved to be controversial. Had Bestia been bribed? Jugurtha was called before the Senate to testify. During his time in Rome, Jugurtha ordered the assassination of Massiva, a rival to the throne who had been living in exile in the capital city. Infuriated, the Romans expelled Jugurtha and resumed the war.

In 110 bc, Postumius Spurius Albinus was elected consul and joined the Roman army in Africa, bringing with him money and supplies. The subsequent campaign proved to be frustrating. As the Romans advanced, Jugurtha retreated; when Albinus pulled back, Jugurtha attacked. To string along the Romans even further, Jugurtha negotiated in bad faith, striking deals with Albinus and then making additional demands and reneging on his agreements. At the end of the year, Albinus returned to Rome, leaving his brother Aulus in charge of the army.

Aulus, a “conceited ignoramus” in Sallust’s words, decided to attempt a winter attack on Jugurtha’s treasury at Suthul, a hilltop fortress surrounded by a swamp that winter rains had turned into a lake. Aulus marched his troops through the waterlogged territory and instituted a siege. Jugurtha, pretending to be weak and unwilling to attack, retreated into the countryside. Sensing victory, Aulus lifted the siege and pursued. While Aulus was blundering ahead, Jugurtha bribed several allied centurions to abandon their posts. Two cohorts of Lugurians and one squadron of Thracian cavalry deserted to his side. The chief centurion saw to it that his rampart was left undefended, and the Numidians were able to climb the walls and storm the Roman camp. The next day Jugurtha forced Aulus to surrender, with his men enduring the additional humiliation of passing under a ceremonial yoke.

The Incorruptible Metellus Goes to War

Outraged and humiliated, the Romans turned to Senator Quintus Caecilius Metellus, scion of an important patrician family. Metellus raised fresh levies of Roman troops and reinforcements from other parts of the Republic. His second in command was the popular Gaius Marius, a veteran of the siege of Numantia. When he deemed his army ready, Metellus invaded Numidia. Once more Jugurtha retreated. Metellus had learned Jugurtha’s art of war and advanced cautiously, with light troops, archers, and slingers in the vanguard and cavalry and light troops on the flanks and rear. His first target was Vaga, just across the border. He quickly reached the town and took it without a fight. Metellus found a country seemingly at peace, with ripe fields and ample herds. Pliant Numidian officials greeted him at every town.

Metellus could not be distracted by peace overtures or corrupted by bribes, so Jugurtha gathered his army for battle. Meanwhile, Metellus marched southwest into the hills around Vaga and arrived before a desolate plain. The plain was bracketed by the hills in the east and the Muthul River in the west. On the north end of the plain lay a tree-studded, two-pronged spur. There Jugurtha deployed his troops, hoping to ambush the Romans. Jugurtha put his infantry and elephants under the command of a subordinate named Bamlicar and placed these troops on the right prong. On the left, Jugurtha arrayed his cavalry and elite infantry.

As Jugurtha had hoped, Metellus decided to establish a camp on the Muthul. But as the Romans advanced onto the plain, their scouts spotted the Numidians. Metellus halted the advance and reorganized for battle. He reinforced his right with three auxiliary cohorts, interspersed archers and slingers between his infantry cohorts, and deployed his cavalry on the wings. Thus reorganized, Metellus resumed the advance. After marching parallel to Jugurtha’s left spur, Metellus faced north, offering battle, but Jugurtha did not dare attack. Wanting to secure a water supply, Metellus sent a flying column of cavalry and light infantry to the Muthul, where they arrived without resistance and built a camp. Then Metellus wheeled left and resumed his march across the plain.

Harassing the Roman Army

The battle began, pitting Jugurtha’s light infantry and cavalry against the heavy infantry of Rome. Jugurtha sent 2,000 light infantry into the hills, cutting off the Romans’ route of retreat. Jugurtha’s cavalry and light infantry rode down from the left prong and swarmed around Metellus’s army, riding in close, unleashing volleys of javelins and other darts, and then scattering before the Roman cavalry could counterattack. The rear of the Roman army was especially hard hit.

Despite the bold Numidian attack, the Roman army slowly made its way toward the Muthul and held off each of Jugurtha’s forays As the battle dragged into the night, Jugurtha ordered his weary Numidians to retreat into the hills. Seeing this, Metellus reformed his ranks and sent four infantry cohorts against the enemy, pushing back the Numidians and repelling a final attack on the Roman camp. The Battle of the Muthul was a total defeat for Jugurtha, who fell back into the interior.

With Jugurtha out of the way, Metellus marched southwest along the river, taking several unfortified towns and living off the land. With his most valuable territory being ravaged by the Romans, Jugurtha led a group of picked cavalry onto the plain, where he followed the Roman army, attacking foragers and rolling up stragglers. The raids slowed Metellus’s advance, as he was forced to send out whole cohorts to forage. Continuing south, Metellus split his army in two, placing one wing under the command of Marius. The two columns marched separately, but remained close enough to support one another should the need arise. Staying in the hills, Jugurtha paralleled the Roman line of march and harassed both commands, withdrawing before Roman infantry could be brought to bear against him.

Saving Zama

Tiring of Jugurtha’s harassing tactics, Metellus decided to attack Zama in the hopes that Jugurtha would feel compelled to fight a major battle defending it. Indeed, once he learned of Metellus’s plans Jugurtha raced to Zama, reinforcing the garrison and exhorting the townspeople to defend their walls. Meanwhile, he took his small force of elite cavalry into the countryside with the intention of striking the Romans at an opportune time.

While he was making his way to Zama, Metellus sent Marius with a pair of cohorts on a foraging expedition to Sicca. Jugurtha learned of the movement and rushed there with about 1,000 cavalry. Arriving at Sicca just as Marius was leaving, Jugurtha formed his troops and urged the townspeople to help attack the Romans. Marius did not bother with the threat to his rear. Instead, he attacked Jugurtha’s cavalry and cut his way out of the trap.

Once Marius rejoined the main army, Metellus attacked Zama. Under the cover of slingers and archers, Roman infantry ran ladders up to the walls and attempted to scale the battlements. Other teams tried to bore through or tunnel underneath the fortifications. As the assault progressed, Jugurtha attacked the Roman camp, which was lightly defended. Seeing the crisis, Metellus sent Marius to retake the camp. Marius quickly fought his way into camp, where he found the Numidian forces scattered and disorganized in the process of looting the Roman tents. Marius drove away the Numidians, inflicting heavy losses.

With Jugurtha still on the loose and night falling, Metellus halted his attack. When he renewed operations the next morning, Metellus sent out cavalry patrols to locate Jugurtha and keep him away from the army. Sensing that Zama was on the verge of collapse, Jugurtha eschewed his normal hit-and-run tactics and unleashed a full assault. The Numidians drove off Metellus’s cavalry screen once again. With a new threat to his rear, Metellus lifted the siege. For the time being, at least, Jugurtha had saved his kingdom.

Political and Military Victories For Metellus

After the failed assault on Zama, Metellus garrisoned Roman-held towns in Numidia and went into winter quarters. The popular Marius undermined Metellus in the ranks and agitated for Rome to appoint him consul. Hoping to end the war before Marius was elected, Metellus opened negotiations with Jugurtha. In exchange for a large indemnity, Jugurtha agreed to surrender but backed out of the agreement at the last moment.

Instead of surrendering, Jugurtha raised a fresh army and engineered a revolt in Vaga, where the Roman cohort was celebrating a winter festival. Soldiers and officers were massacred as they ate and drank. When word reached him, an enraged Metellus gathered some Numidian cavalry that had come over to him and marched a legion to Vaga. As he approached the city, he placed the Numidians in the front ranks so that the town’s inhabitants would assume he was Jugurtha. The ruse worked, and the Romans entered the city unmolested and put the populace to the sword.

In the wake of his victory at Vaga, Metellus was reelected consul. He sent Marius back to Rome and systematically pacified the countryside. Jugurtha, isolated and running out of men, retreated to the desert fortress of Thala in the southwest. Metellus followed, imitating the Numidian way of war. He stripped the pack animals and ordered his men to carry 10 days’ rations and extra water skins. Scouts ranged ahead, gathering cattle and ordering friendly Numidians to deliver water on the line of march. Arriving at Thala, Metellus lay siege to the town. Jugurtha fled, leaving Thala to its fate. Metellus took the town after a six-week siege.

After capturing Thala, Metellus took Cirta, breaking the back of Jugurtha’s resistance. Determined to continue the fight and needing troops, Jugurtha made an alliance with King Bochus of Mauritania, his father-in-law, and recruited desert mercenaries. Jugurtha gathered the new army near Cirta. Before Metellus could attack, word arrived that he was being replaced by the newly elected Marius.

The Campaign of Marius

Jugurtha fell back to the isolated desert stronghold of Capsa. Marius, now the Roman commander, gathered the army at Sicca, where he stripped his troops of all but their weapons and water skins. After a lightning three-day march, the Romans took the town in a quick assault. The fall of Capsa demoralized Jugurtha’s supporters. With the Numidians fleeing in terror of him, Marius was able to take several other towns.

Marius began the 106 bc campaign with another bold attack, this time against Jugurtha’s treasury, which he took after a long siege. After consolidating his hold in the west, Marius marched for winter quarters in Cirta. The enemy was not idle. Jugurtha and Bochus reunited their armies in time for an attack on Marius. The assault began near sunset as the Romans were readying their encampment. From all directions, small groups of Moorish and Gaetulian cavalry swooped in on Marius’s men. Marius gathered his scattered cavalry and led them to the relief of his camp.

Marius sent one of his aides, the equally ambitious Sulla, with some cavalry to secure a nearby hill. Then he fell back to a second hill behind the cover of Sulla’s screening force and waited for first light. Believing that they had won the battle, Jugurtha and Bochus camped at the Roman position. When dawn broke, Marius formed his troops for attack and charged down the hill, taking Jugurtha and Bochus unaware. The sleeping enemy was routed, their camp overwhelmed, and more were killed than in any previous battle.

Undeterred, Jugurtha and Bochus followed the Romans and surrounded them just short of Cirta. The first strike was delivered by the Numidians against Sulla, whose cavalry absorbed the blow, reformed and counterattacked, driving them from the field. Next, Jugurtha led his cavalry against the Roman front, which held against several attacks. Then Bochus and his Moors hit the Roman rear, which also held. Unable to penetrate the Roman lines, Jugurtha resorted to spreading rumors that Marius had been killed. Sulla returned from the chase and hit Bochus’s unprotected flank. After routing the Moors, Sulla turned his attention to Jugurtha, surrounding and destroying his cavalry.

Sic Transit Gloria

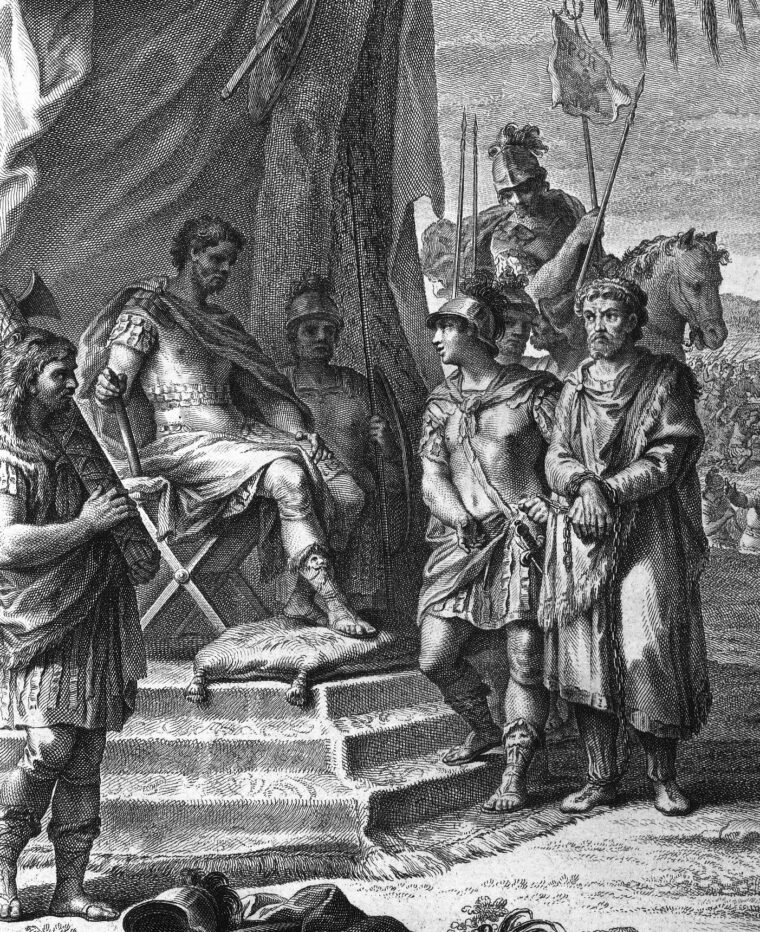

Jugurtha had lost another battle, but he and Bochus again escaped. However, as Marius was preparing winter quarters Bochus sent word that he wanted peace. The consul dispatched Sulla to make the following demand: in exchange for Roman friendship, Bochus would have to deliver Jugurtha. Bochus agreed. He arranged for a meeting with his unsuspecting son-in-law, at which he slaughtered the king’s entourage and turned him over to Sulla.

The desert warrior was brought in chains to Rome and thrown into the Tullianum, the city’s infamous underground prison. There Jugurtha was set upon by other prisoners, who tore off his clothes and ripped off his earlobes to get at his gold earrings. Roman historian Plutarch recounted the sordid aftermath: “The wretch, after struggling with hunger for six days and up to the last moment clinging to the desire of life, paid the penalty which his crimes deserved.” The king who had controlled an entire desert kingdom starved to death, alone and unmourned. Sic transit gloria, indeed.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments