By Earl Echelberry

By the end of the winter campaign of 1861-1862, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had shattered the Confederate defenses in northwest Tennessee with a combined land and water attack on Forts Henry and Donelson, forcing General Albert Sidney Johnston to abandon his bastion at Nashville and retreat southward. Johnston eventually halted the retreat and began to concentrate his forces at Corinth, Miss., a key railroad junction just south of the Mississippi-Tennessee border. From there he would be able to protect the Memphis & Charleston Railroad while plotting his next countermove.

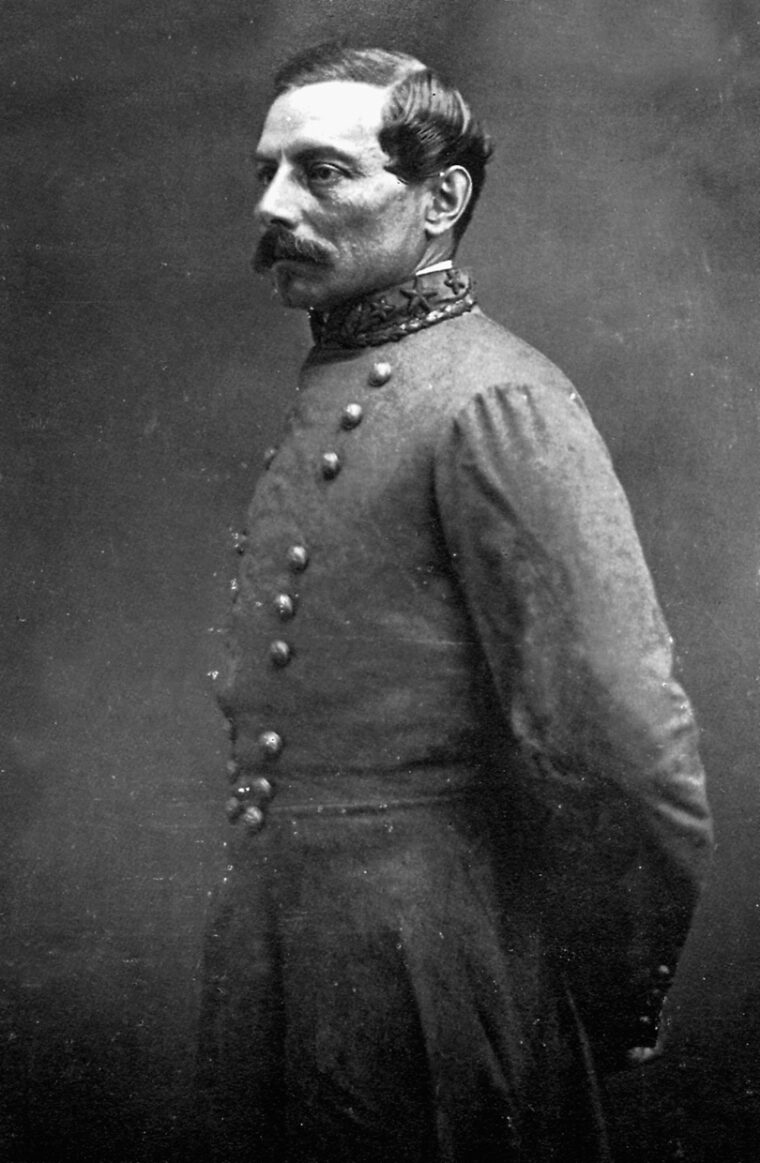

At Corinth, Johnston reinforced his army with 10,000 troops under Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg, coming up from western Florida, and 5,000 more from New Orleans under the command of Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles, swelling his army to some 44,000 men. Meanwhile, President Jefferson Davis sent General Pierre G.T. Beauregard west to assist Johnston as his second-in-command.

The Next Phase of the Federal Offensive

The Confederate withdrawal caught the Federals by surprise, and it took some time to initiate a new offensive. Army politics reared its ugly head after the victories at Forts Henry and Donelson, and the victor of those battles—Ulysses S. Grant—was supplanted by Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, commander of the newly formed Department of the Mississippi. To make matters worse, Halleck gave Grant’s old command, the Army of the Tennessee, to Maj. Gen. Charles F. Smith, who had no experience whatsoever in directing such a large body of men. Nevertheless, in mid-March Smith sent Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman scouting down the Tennessee River to locate and exploit any weakness in the Southern defenses. Sherman traveled down the Tennessee to northern Alabama and attempted to cut the Memphis-Charleston Railroad. Failing to do so, he retreated upriver and selected Pittsburg Landing, near Savannah, Tenn., as the place to launch the next phase of the Federal offensive.

Reinforcing Sherman’s advance force, Smith camped on the west bank of the Tennessee River to await the arrival of Maj. Gen. Carlos Buell, who was leading the Army of the Ohio south from Nashville. The plan was to use the combined strength of both armies to attack the gathering Southern forces at Corinth and seize the railroad there, thus breaking a crucial link between the lower Mississippi Valley and the flourishing cities on the Confederacy’s east coast.

An Even Match of Soldiers

Smith’s divisions camped in a thickly wooded area that was the shape of an irregular wedge, with each side of the wedge being three to four miles long. Snake Creek and Owl Creek made up the north and west legs, while the east side was bounded by the Tennessee River. The southeast side was formed by Lick Creek and its branch, Locust Grove Creek; the Shiloh Branch of Owl Creek bordered the southwest side. No entrenchments were constructed due to a lack of engineering expertise in the army and the somewhat casual attitude fostered by the general staff that the Confederates lacked the ability or desire to become the aggressor.

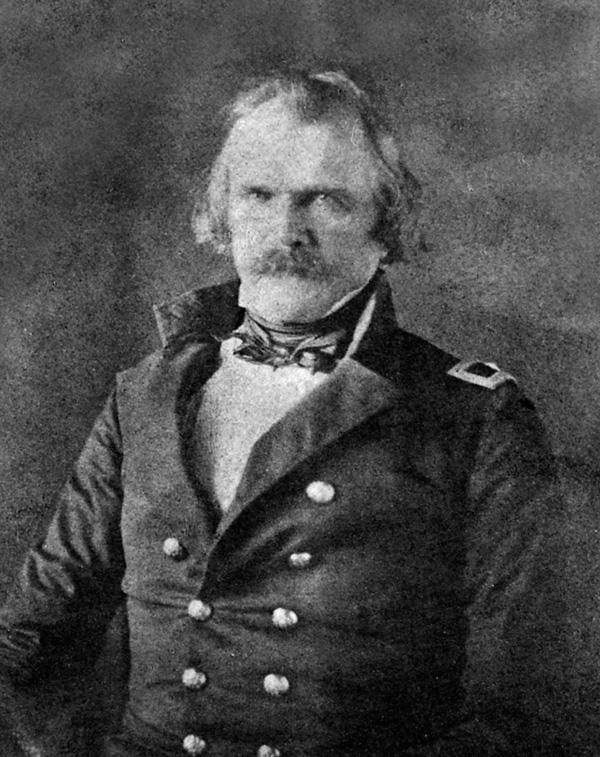

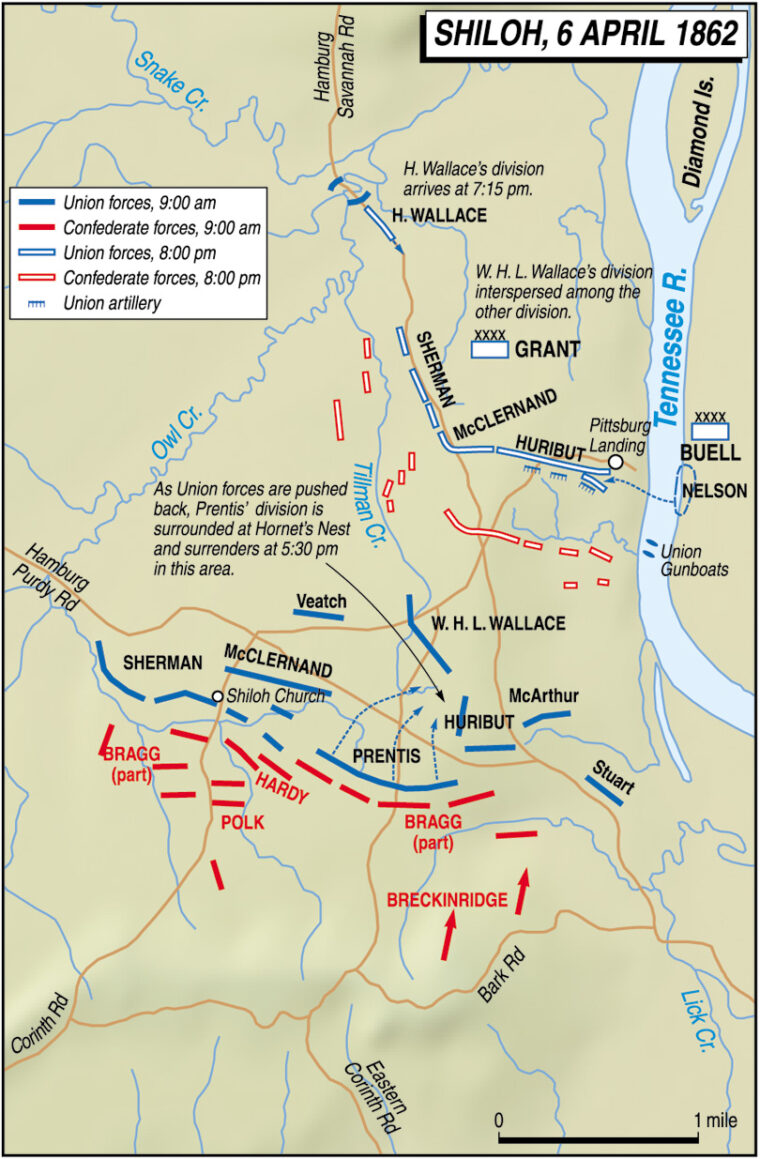

While the Union Army lounged about awaiting the arrival of Buell’s army, Beauregard, in his role as Johnston’s chief of staff, began assembling one of the largest military forces west of the Appalachians. He divided the army into three corps: Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk commanded the I Corps, Bragg commanded the II Corps, and Maj. Gen. William Hardee commanded the III Corps. Major General John C. Breckinridge took charge of the reserve corps. By April 2, Johnston had a combined strength of 44,700 men, only slightly less than the Army of Tennessee’s 48,000.

Launching a Pre-Emptive Attack at Pittsubrg Landing

Johnston feared that the united Federal armies would move against him soon, and on April 2 he decided to launch a preemptive attack against the Union position at Pittsburg Landing. Johnston planned to execute a turning movement with his army to get around the Federal left and drive toward the landing, thereby forcing the Federals to retreat from the river into the swamps of Owl Creek, which flowed just north of Shiloh Church, a Methodist meeting place three miles west of Pittsburg Landing. Orders were issued on the 3rd, and the Army of the Mississippi began its movement toward the Federal camp. However, the roads from Corinth to Shiloh were few in number and poor in quality, and the land was covered in heavy woods and frequently cut by ravines and swamps. Even though Johnston’s plan called for his men to be in position to launch their attack on April 4, it took them three days to cover a grand total of 20 miles.

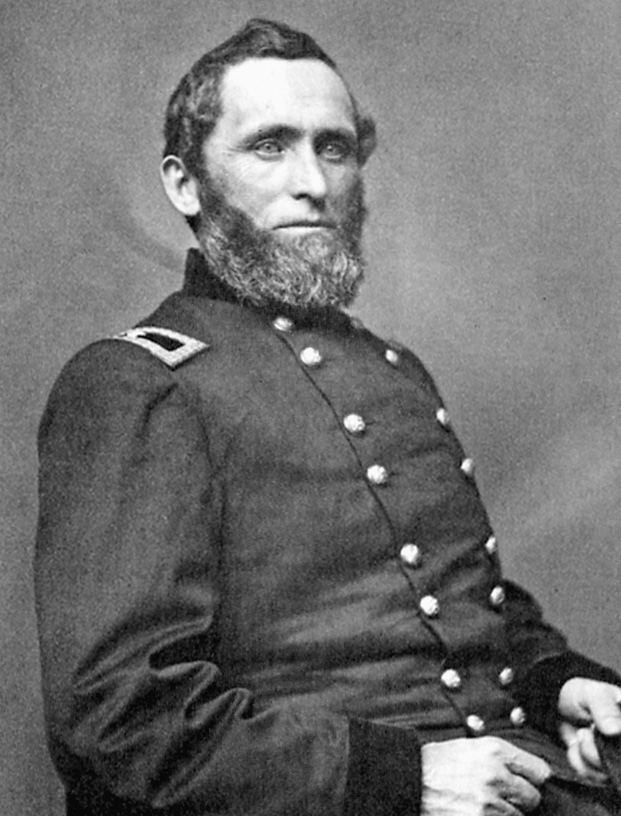

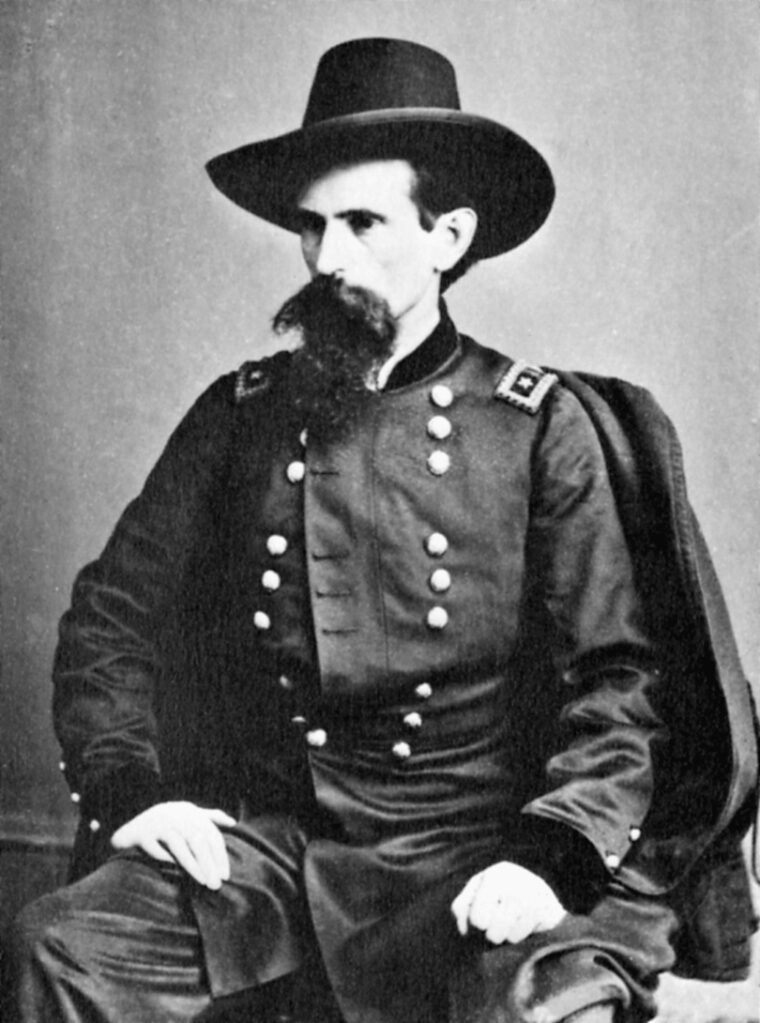

The combination of unfamiliar terrain, rainy weather, an inexperienced makeshift army, and a weak command structure contributed to a sputtering start and a critical delay. Not until the 6th was the Army of the Mississippi finally in position to launch its attack. Smith, who had badly injured his leg when he slipped getting into a skiff at Savannah—he would die of an infection a few weeks later—had arranged his forces across the southern base of the wedge between Owl and Lick creeks. On the right flank, near Owl Creek and the Hamburg-Purdy Road at Shiloh Church, was Sherman’s 5th Division.To Sherman’s left and in an extreme forward position was Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss’s 6th Division. A mile and a half to the rear was Maj. Gen. John McClernand’s 1st Division. To McClernand’s left was Brig. Gen. William Wallace’s 2nd Division. Brig. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut’s 4th Division, aided by Colonel David Stuart’s and Brig. Gen. John McArthur’s detached brigades, held the extreme left, anchored on the banks of Lick Creek. Major General Lew Wallace’s 3rd Division was positioned across a bridge north of Snake Creek, connected to the rest of the Union Army by the Hamburg-Savannah Road.

Confederate Cavalry Three Miles From Camp

Grant, now restored to overall command of the Army of the Tennessee after the brief misunderstanding with Halleck, established his headquarters a few miles away at Savannah. Reviewing Smith’s troop placement, he saw no need to make any changes or to prepare a new line of defense. The Union front remained vulnerable to attack. Although confident that Johnston’s army would not dare attack his position, Grant nevertheless ordered a reconnaissance toward Corinth on April 3. The men had not traveled more than three miles from camp before they ran into a company of Confederate cavalry. No shots were exchanged and both sides retired unmolested, but an alarmed Prentiss kept sending out scouting parties to reconnoiter the area in front of his position. When they encountered new Confederate resistance on the 5th, they immediately reported the encounter. Grant, however, treated this as an isolated event, and no further defensive action was undertaken.

Major General William Nelson arrived in Savannah with the advance division of Buell’s army of the Ohio on April 5 and reported immediately to Grant. New orders were cut to move Nelson’s 4th Division to Pittsburg Landing as soon as adequate transportation became available. Five Union divisions now were camped on a rugged plateau, while Nelson’s wearied division rested just across the river. The remainder of Buell’s army was still bivouacked a full 30 miles up the road from Savannah.

Losing the Element of Surprise

Beauregard, believing that the element of surprise had been lost due to the previous skirmishing between pickets, recommended calling off the attack. Johnston disagreed, reasoning that a quick, decisive strike would destroy Grant’s army. Silently, in a heavy rainstorm, the Confederates moved to within four miles of the Federal camp. Halting at the intersection of the Hamburg-Purdy and Corinth-Pittsburg Roads on the stormswept night, the Confederates hunkered down to wait for dawn.

Long before first light, Johnston’s army was up and fed, their cumbersome blankets and knapsacks stripped off as they prepared to move out. As the sun began to peep through the young foliage of the forest, 44,000 Confederate soldiers who had never seen combat, led by officers who had never attempted to manage a force of this magnitude, moved through dense woods intercut with deep ravines. Their advance, over pathways that resembled Indian trails more than roads, made it difficult for them to maintain a solid, linear formation. Communication between the advancing divisions was an equally daunting task. Johnston personally led the brigades from the front, while Beauregard remained in the rear directing reinforcements and supplies.

Battle Lines 500 Yards Apart

While Johnston was still concentrating his forces, a small Federal reconnaissance force passed through its own picket lines and moved forward. Entering the forest, the men marched in the direction of the Corinth road. The going was difficult because of the thick canopy and uncultivated brush. Upon breaking clear of the forest, the Union force stumbled directly into the middle of Hardee’s corps. More startled that anything else, both sides exchanged harmless musket fire before the Federals retreated to their camp.

While the main Union force went about its daily routine, blithely unaware of the most recent skirmishing, the gray-bloused Confederates made their final preparations. The plan was to attack along the broad front of the Federal line, which extended from Owl Creek to Lick Creek, a distance of three miles. Stacked into three distinct lines of battle, Hardee commanded the initial strike force, supported by Bragg and Polk in a second wave. Breckinridge would bring up the rear. Each battle line was separated from the other by a distance 500 to 800 yards.

The slashing attack began with a deep roar of heavy cannon, followed by the sharper rattling of musketry. Storming forward, the Confederate infantry attacked on all fronts as squadrons of cavalry charged both wings. With the force of a spring thunderstorm, Hardee’s men fell upon the Federals. Pausing to deliver a second volley of fire, the surging Confederate masses charged Sherman’s raw regiments. The first to bear the shock of the oncoming Confederates, Colonel Jesse Hildebrand’s brigade quickly retreated in panic before the onslaught. Soon the brigades of Colonels Ralph Buckland and John A. McDowell came under fire as well and quickly sought shelter as the two sides began to blaze away at will.

Early in the assault, Hardee spotted a gap between Sherman’s and Prentiss’s lines that appeared to be an open highway to the Federal flanks and rear. He quickly ordered the brigades of Colonels Randall Gibson, Patton Anderson, and Preston Pond into the gap in an attempt to sweep around Sherman and enfilade his left flank. Sensing the mass confusion in his ranks, Sherman withdrew toward McClernand’s camp. Upon reaching the Hamburg-Purdy Road, Sherman’s men formed a new defensive line. Seeing Sherman falling back, McClernand pulled in his divisions and formed them along the Corinth-Pittsburg Road. The right wing of the Federal army was in a solid defensive position, but the withdrawal had unwittingly exposed the center’s right side.

By mid-morning the Confederates seemed to be within easy reach of victory. Heartened by their initial success, the graycoats stormed toward the enemy’s newly established defensive line. Step by step they came. As they got within musket range, they were greeted by a furious barrage of bullets and driven back. The gap between the two armies was filled with deadly fire. Soon the bellowing of cannon was added to the ripping sound of explosive fragments raining death all along the battle line.

With the support of accurate cannon fire, the Confederates surged forward yet again. The solid blue line seemed to dissolve as more and more Federals fled backward. Eventually, the bluecoats collected themselves and organized a new battle line, this time across Tilghman Branch. With this withdrawal the battle fell into a deadly rhythm of battery pounding battery, while each side prepared for another assault. Artillery shells slicing through the branches signaled the arrival of another Confederate column of cavalry and infantry. From one end of the line to the other, a sheet of red flame erupted. Protected by a steel canopy of shells, Stuart’s men stubbornly stood their ground.

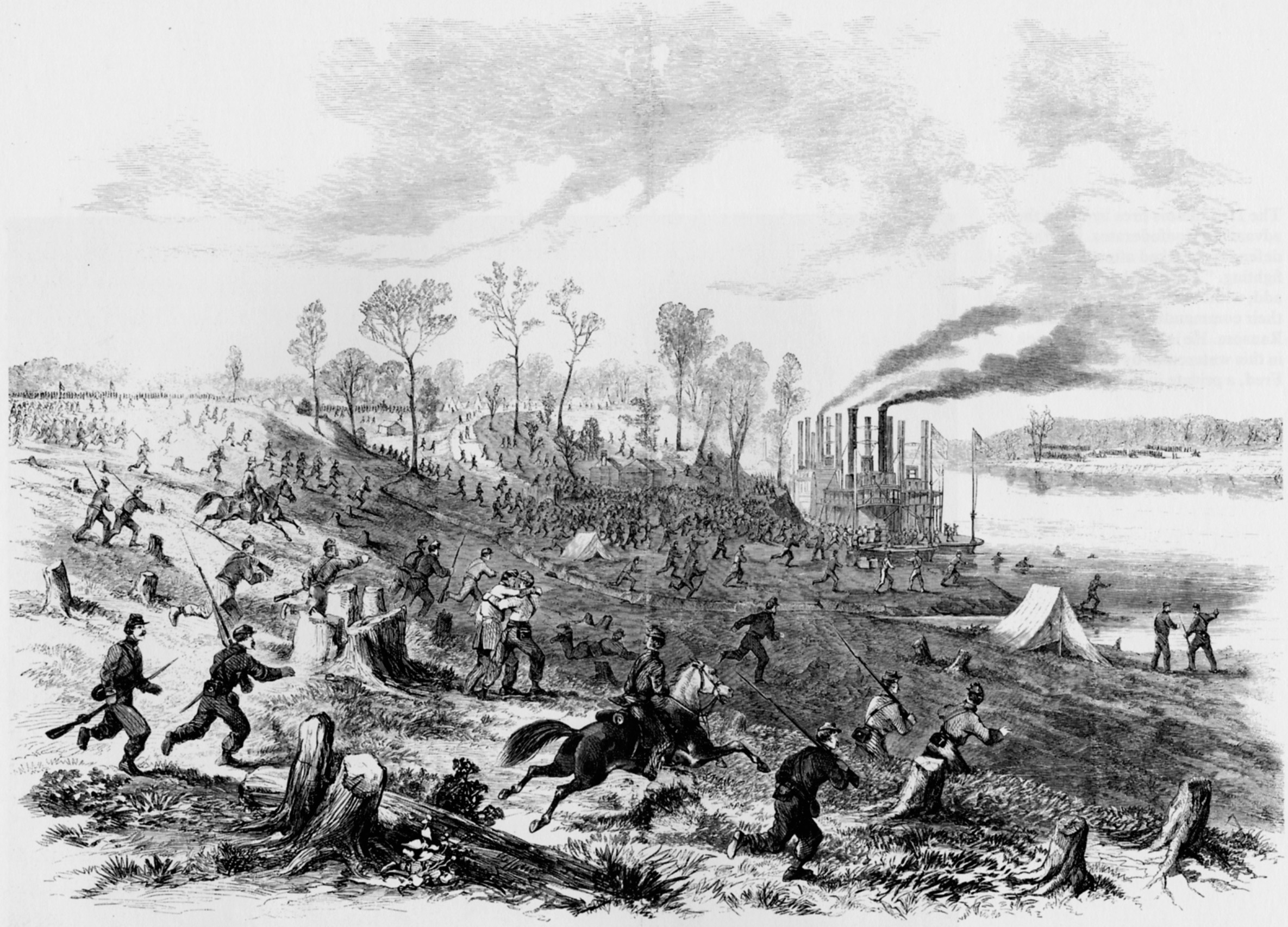

For hours the battle raged. Over rolling hills, wooded forests, and deep ravines the two sides fought savagely. Dissatisfied with the progress of the battle, Bragg directed the three brigades of Brig. Gens. James Chalmers, John Jackson, and John Bowen to press their attack on the Federal left. With the release of a new storm of leaden hail, the Confederates renewed their assault. The Union line began to stagger and break under the onslaught, crowding the roads leading to the landing in a disorderly retreat. After seven hours of being heavily assaulted by Confederate forces, Stuart’s brigade broke and tumbled back toward Pittsburg Landing, passing through the new defensive line formed by Grant’s siege guns and Hurlbut’s 4th Division.

Meanwhile, in the Union center, Prentiss ordered his division into line and advanced a short distance to engage Polk’s and Bragg’s men. With a heavy exchange of volleys, the Confederates began slowly pushing Prentiss’s men back toward their tents. From behind every tree the Southerners poured a deadly fire into the Union forces. Somehow Prentiss’s men held the attackers in check. Soon, however, the Confederates were reinforced and pressed forward again, first on the right and then on the left, until they were in full possession of Prentiss’s camp.

Stopping to plunder the vacated camp, the Southerners inadvertently slowed their own attack, providing Federal commanders with much-needed time to reform their broken lines and prepare to meet the next assault. Prentiss’s two brigades, broken and scattered, retreated toward Hurlbut’s position. Amid the noise and confusion of battle, Prentiss halted and reformed his men along a sunken dirt road two miles to the rear. Sensing the collapse of the center, William Wallace committed the brigades of Colonels Thomas Sweeny and James Tuttle in support of Hurlbut’s two brigades and the remnants of Prentiss’s brigades. From this reinforced position, Prentiss was able to check the Confederate advance.

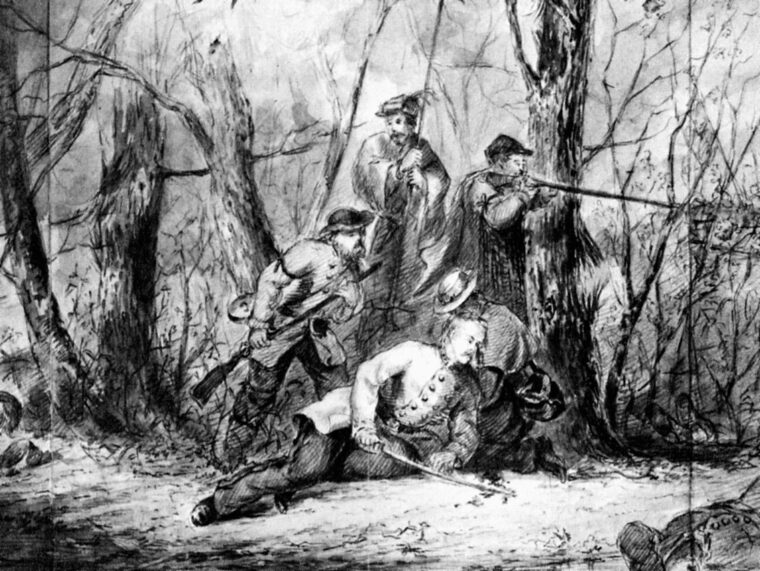

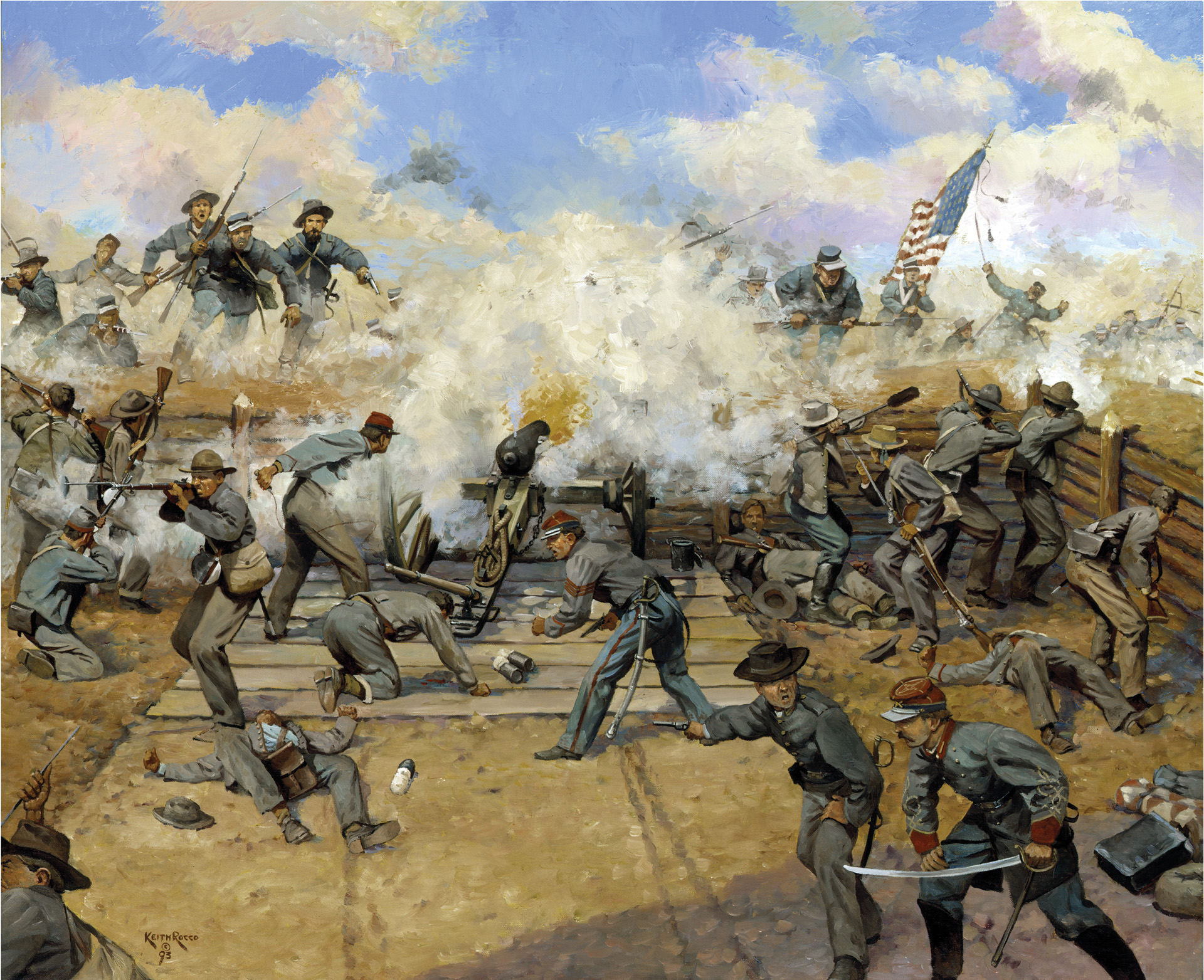

As hour followed hour, a series of irregular, confused, and bloody confrontations occurred. Bullets buzzed like hornets in the heavy woods and dense undergrowth, giving the evocative name “Hornet’s Nest” to this part of the battlefield. For the next six hours, the Federal line wavered but never broke under repeated Confederate assaults. Frustrated, Bragg ordered Gibson to launch a head-on attack at the center of Prentiss’s line. Gibson’s men charged with muskets leveled into the impregnable Hornet’s Nest, where they were greeted with an appalling crash of sound and a fusillade of hot metal from Captain Andrew Hickenlopper’s massed cannon. Again and again Gibson’s men surged forward, only to be forced back by the quick-firing artillery. Finally, Johnston realized that his army was being wasted in such frontal assaults and ordered Breckinridge’s reserve corps to attack the Federal position at Sarah Bell’s peach orchard, which lay just east of the Hornet’s Nest.

Johnston, waving his sword, launched his assault on Hurlbut’s position. During this struggle a Minie bullet slammed into Johnston’s leg behind his right knee, severing his femoral artery. Not realizing at first that he was grievously wounded, Johnston continued to direct the attack until he became faint from loss of blood and swooned in his saddle. Tennessee Governor Isham Harris, on hand that day as a civilian aide, caught the stricken general and lowered him to the ground. When Harris removed Johnston’s boot, he found it full of blood. As the governor and other high-ranking officers fretted impotently above him, Johnston slowly bled to death, a six-foot-long stream of blood trailing from his leg. A field tourniquet that might have staunched the deadly flow of blood was found later in Johnston’s pocket.

With the death of Johnston, Beauregard assumed command of the Confederate forces. Having forced back the Federals’ left and right flanks, the new commander prepared his forces for one final push. Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles’ 1st Division was ordered to move 62 cannons into position to support the renewed Confederate attack.

The withdrawal of Sherman’s and McClernand’s troops behind the Tilghman Branch exposed the army’s flanks. Under the protection of Ruggles’ artillery, Breckinridge smashed into Hurlbut’s position, forcing him back to Pittsburg Landing, where he joined Sherman and McClernand in forming a new defensive position along the Hamburg-Savannah Road. This, in turn, exposed Prentiss’s left flank, compelling him to change fronts under fire—always a risky maneuver. With Ruggles’ artillery continually hammering the Federal line, Polk and Hardee attacked Prentiss and William Wallace from both flanks and front. Wallace was fatally wounded by a whirring piece of shrapnel, and his line crumbled and fell back. This left Prentiss’s division surrounded on three sides.

With a chorus of Rebel yells, Beauregard’s fresh brigades entered the fray, swooping over the field and capturing Prentiss and 2,200 of his officers and men. This effectively ended any resistance in the Federal center. Having taken the Peach Orchard and the Hornet’s Nest, the Confederates continued pushing northward for a time, but finally stopped to eat and rest. The men were famished and exhausted.

Earlier that morning, when word of the battle reached Grant at his headquarters in Savannah, he ordered Nelson to assemble his troops opposite the landing, where they were to be ferried across the Tennessee River. Grant then hastened to the landing, where he found his former camps in the hands of the enemy and the remnants of his army cowering beneath the river bluff under continuous and heavy bombardment. Pushing his way forward, Grant met with his front-line commanders and discovered that Sherman, Prentiss, and McClernand were all falling back. A new line was established using Wallace’s and Hurlbut’s brigades in support of the retreating Federal force, and Grant sent urgent messages to both Buell and Lew Wallace to move with all speed toward Pittsburg Landing. Galloping along a sunken road, Grant was nearly killed when a Mississippi battery fired a charge of grapeshot into his group. A shell fragment struck his sword just below the hilt, breaking his scabbard and blade in two. After this, Grant never bothered to wear a sword.

Throughout the afternoon, Grant calmly directed the establishment of a new defensive position anchored on the left by the Tennessee River and on the right by Snake Creek. To strengthen the line Grant mounted batteries of heavy artillery on the high ground behind the Tilghman and Dill branches. Next, he moved into line the retreating remains of Hurlbut’s, McClernand’s, and Sherman’s divisions. Lew Wallace’s 3rd Division hurried along the Hamburg-Savannah Road to move into position on the left flank.

As the sun began to set on April 6, the remnants of the Army of the Tennessee took up their final defensive position as Federal batteries flung hot metal across the ravine at the enemy. To this barrage was added the ordnance of the gunboats Lexington and Tyler, which swept the Confederates’ right flank with steaming broadsides of eight-inch shells.

On the opposite side of the river, Confederate batteries were pushed forward and responded to the cannon fire by throwing shells across Dill Branch into the Federal position. The Army of the Mississippi’s new alignment had Bragg on the right flank, Polk in the center, and Hardee anchoring the left flank above the Corinth-Pittsburg Road near Owl Creek.

Eager to press the attack, Bragg gathered his exhausted infantry and prepared for one final assault to ensure victory. This honor fell to Chalmer’s and Jackson’s brigades, and they moved forward across the ravine and up the opposite side. Coming within musket range, the men were met with a murderous fire from the rallying Federal forces. Easily repulsed, the exhausted and broken brigades scrambled back through the dense foliage and waded back to safety on the opposite bank. Beauregard, realizing that his lines were in disarray and that the Federal position was virtually impregnable, decided not to hazard another attack. With darkness descending on the battlefield, he withdrew his disorganized forces and regrouped for a new assault in the morning.

As Shiloh’s first day of slaughter was ending, Nelson led his division through the interminable swamps and pathless bottom lands to the eastern bank of the Tennessee River. Colonel Jacob Ammen’s brigade was the first to reach the eastern bank, where two Union steamers waited under fire. As the sky burst into flames, the blueclad soldiers boarded the steamers and made for the opposite bank, where they were greeted with the metallic sound of bursting shells and the occasional whisper of a stray bullet as it sliced through the air during the final Confederate assault of the day.

Throughout the night, Grant’s army was reinforced by new divisions from the Army of the Ohio, while Lew Wallace’s reserve division arrived from Crump’s Landing. The timely arrival of these 22,500 reinforcements allowed Grant to lengthen his defensive perimeter. The three divisions from Buell’s army were placed on the left flank of the Federal line. In the center were Hurlbut’s and McClernand’s relatively intact divisions and the badly mauled divisions of Sherman and William Wallace. On the right flank, Grant had Lew Wallace’s fresh 5,000 men. At midnight a violent thunderstorm broke, announcing the end of the first day’s fighting,

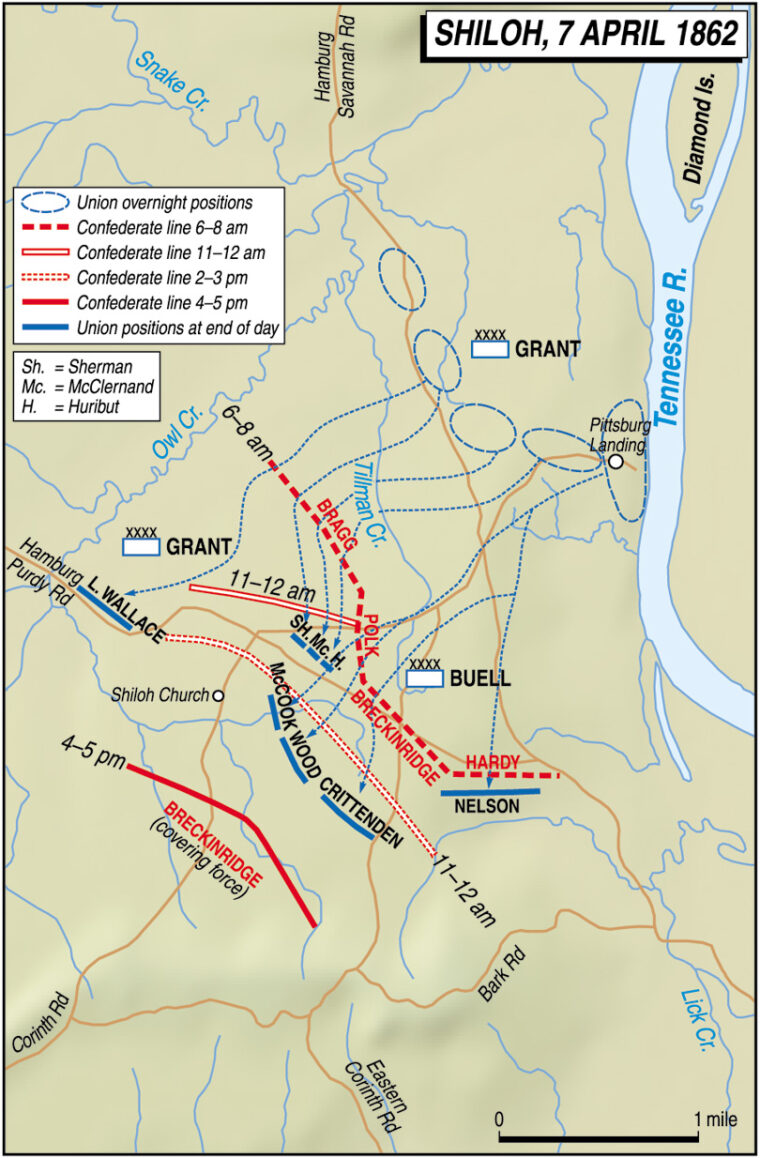

Before the sun rose over the battlefield, both sides made plans for the second day of battle. Grant had at his disposal a combined force of 40,000 men against Beauregard’s 30,000 men. Believing that victory was still at hand, Beauregard’s army had retired behind the Hamburg-Purdy Road to await the coming of dawn. The Confederate line had Hardee on the extreme right next to the river, with Polk and Breckinridge in the center and Bragg on the extreme left.

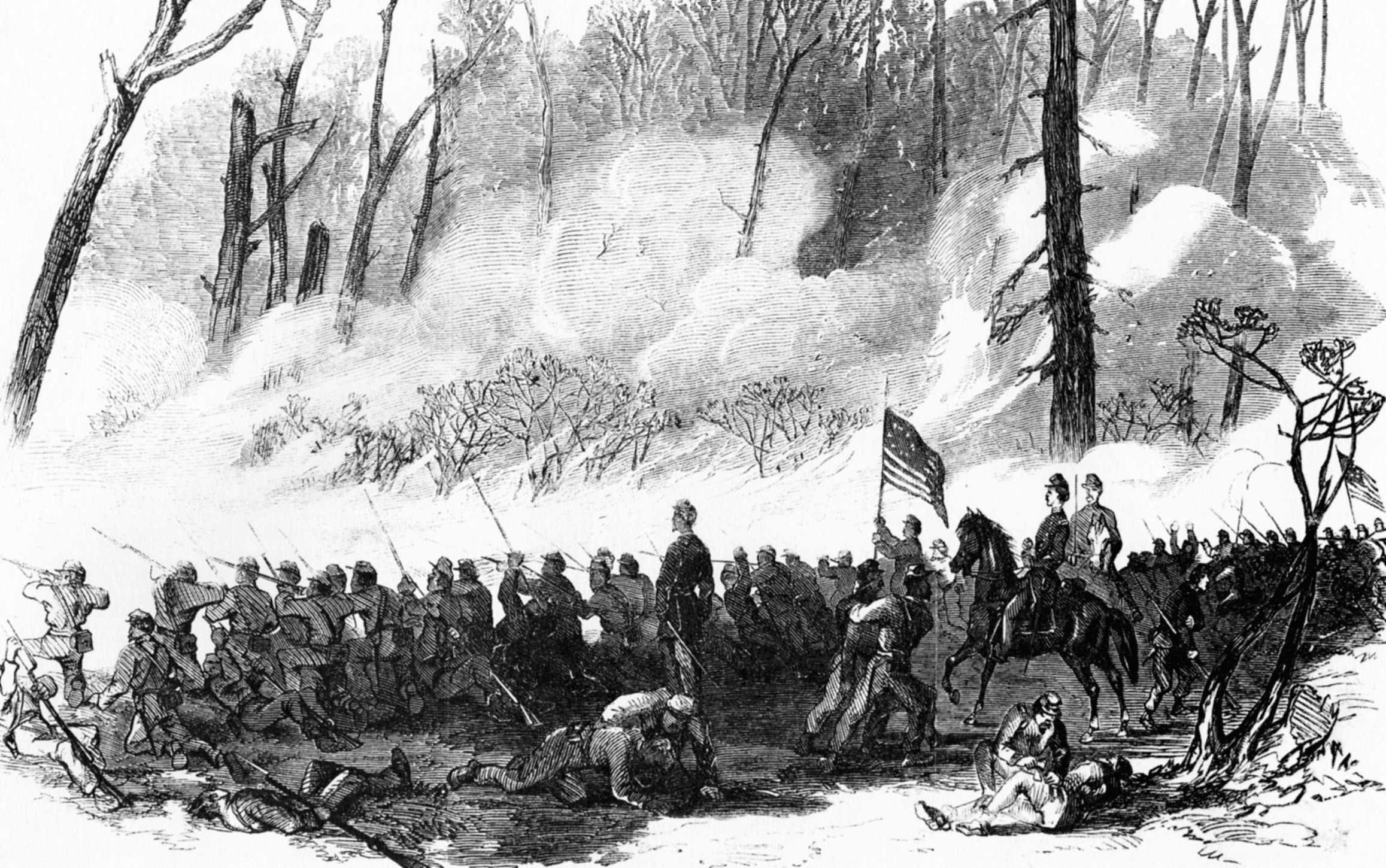

Seizing the initiative, Grant’s newly inspired officers aroused their men from an uneasy slumber and prepared them to renew the fighting. In silence the Federals arranged an aggressive counterattack. With the sun about to peek above the horizon, a thin line of skirmishers detached themselves from their defensive perimeter. In a few moments they passed into the desolation of the previous day’s struggle. Littering the battleground in every direction were discarded knapsacks, canteens, blankets, and rifles with bent barrels or splintered stocks. Dead bodies lay everywhere. Following the skirmishers, Nelson’s advancing brigades silently struck out toward the Confederate lines. Brig. Gen. Thomas Crittenden’s brigades were behind and on Nelson’s right flank as they steadily marched toward the Confederate position.

After advancing about a mile, the Union troops were assailed by Confederate artillery. Moving up their own batteries, a heavy exchange ensued. Taking charge, Buell dressed his lines, forming Brig. Gen. Alexander McCook’s forces on Crittenden’s right and Nelson’s on the left flank and extending his line of attack from a point southeast of the Hamburg Road to Hurlbut’s flank. All the while the ear-blasting exchange of cannon fire continued.

Even before first light of day, Lew Wallace’s field guns had begun shelling the Confederate batteries posted on a bluff in front of his line, forcing them to pull back. Following on the heels of the retreating Confederates, Wallace’s fresh troops soon occupied the hill. Perceiving that the enemy’s withdrawal from the bluff had exposed their own left flank, Wallace prepared to shift his line of attack. Hoping to turn the Confederate left, he left-half-wheeled his division, leaving a gap between his division and Sherman’s. The Confederates immediately tried to take advantage of the gap, but Wallace’s cannon were able to keep them at bay. The battle reduced to exchanges of cannon fire, Sherman moved forward in support of Wallace’s left flank.

It was just past noon when Wallace again changed fronts to attack, with Sherman still on his left in support. As Wallace’s first brigade moved forward, a squadron of Confederate cavalry dashed out of the woods toward his temporarily exposed flank. After repulsing this attack, Wallace ordered his division to keep pressing on. With skirmishers leading the way, the main body of Union troops moved out of the forest and were starting across an open space when the forest exploded and the sickening sounds of bullets hitting soft flesh filled the air. Expecting to find only a screen of skirmishers, Wallace had run headfirst into a fully organized Confederate battle line that had coolly held its fire until the Federals had advanced into the killing zone. Once again the Union advance was halted.

Sherman’s brigade soon gave way, exposing Wallace’s flank. A heavy mass of Confederates rushed forward to take advantage of the break and isolate Wallace from the rest of the army. For a while the situation seemed critical, but Sherman’s line recovered and moved abreast of Brig. Gen. Lovell Rousseau’s brigade, reestablishing a solid line of attack. The Confederates found themselves hard pressed all across the battlefield. The battle steadily collapsed toward the center.

In a courageous if foolhardy move, Colonel William B. Hazen’s newly arrived brigade charged a Confederate battery. Overextending his lines and exposing both his flanks to a withering fire of shot and canister, Hazen was forced to retreat with a loss of one-third his men. Colonel William S. Smith’s brigade, not slackening its pace, charged into the melee on Nelson’s right flank. Meanwhile, Union artillery silenced the Confederate batteries. Reinforced with Brig. Gen. Jeremiah Boyle’s brigade, Nelson drove the Confederates back, exposing their cannon.

The Federals steadily pressed forward. Step by step the Confederate lines retreated. Crittenden’s division, supported by two regiments of Hurlbut’s division, advanced against the Confederate center-right. While the cannoneers feuded, the Federal columns pushed the Confederates back, sweeping everything before them. Bush by bush and tree by tree, the Confederate center was forced to give ground.

McCook ordered Rousseau’s brigade to advance on the Confederate center-left. Seeing Rousseau’s brigade moving up in support of Crittenden’s right flank, Beauregard countered by sending Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s division to engage the enemy. The exchange of fire, which had been hot enough as it was, now redoubled, stalling the Federal attack. McCook deployed the brigades of Colonels Edward Kirk and William Gibson to the right and rear of Rousseau’s brigade. This added pressure forced the Confederate center to gradually give way.

Rousseau, finding his advance no longer blocked, charged forward again, crashing into Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s brigade at the Corinth-Pittsburg Road. Again the Confederates put up a stiff defense, but after the loss of another 1,700 killed or wounded they were forced to abandon their position and fall back. With the retreat of the Confederates’ left flank, remnants of the army collapsed inward around the Shiloh meeting house. The Confederate cause was becoming desperate. Beauregard, moving to and fro, urged his troops to rally once again and somehow managed to sort out the disordered fragments of his army for a last-ditch stand.

Upon reaching a wooded area 500 yards east of Shiloh Church, McCook’s division ran into a wall of grape and canister from two Confederate batteries followed by dozens of gray-clad infantrymen suddenly swarming out of the woods. With a resounding crash the Confederate line surged forward, only to be pelted in turn by the waiting Federal battalions. Stunned by a shattering volley of fire, the Southern attack collapsed. A second Confederate wave swept down, pouring in fire and forcing the blue line to stagger. Union reserves sprang forward, filling the gap left by their retreating comrades. This was met with a third attack as the desperate Confederates charged over their own dead and wounded with bayonets lowered. However, lead always wins over steel, and as quickly as it began the Southern attack evaporated.

Hastily fixing their own bayonets, the Federals charged after the retreating enemy. Unable to withstand the assault, Confederate cannoneers abandoned their guns and fled with the infantry across an open space into the woods beyond. With the support from Hurlbut’s brigades on the left and McClernand’s brigades on the right, McCook’s force advanced as the Confederates steadily gave ground.

The last Confederate attack served only to cover their withdrawal from the battlefield. Beauregard, realizing at last that the day was lost, ordered a total retreat at 1:30 that afternoon. Commencing on their right flank and spreading to the left, the defeated men in gray retreated through the woods to a commanding ridge behind Shiloh Church. There they were met by reserves, who stood in line to support their withdrawal and blunt any further Federal advance.

The sound of battle ebbed and flowed as the exhausted men in Grant’s army moved doggedly forward. Much of the fight had gone out of them as well, and they stopped to catch their breath. A new attack against the retreating Confederates was not in the cards so the remainder of the Confederate forces quit the field unmolested and silence fell over the ravaged countryside. The Battle of Shiloh had ended. During the night the greatly disorganized Confederates withdrew to their fortified stronghold at Corinth. Possession of the grisly battlefield passed to the victorious Federals, who reclaimed their camps and made an exhausted bivouac among the dead.

Johnston’s massive concentration at Corinth and the surprise attack at Pittsburg Landing had presented the Confederacy with a golden opportunity to reverse the course of the war. The misbegotten aftermath left the invading Union forces poised to capture Corinth. This in turn would open up the entire Mississippi Valley, making Memphis and Vicksburg vulnerable to attack. The final number of dead or missing was 13,000 on the Federal side and 10,500 on the Confederate, including one of its most valuable generals. More men had fallen in two days at Shiloh than had fallen in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War combined. Across the nation spread the sickening realization that the fighting would not end quickly and that the idea of an easy victory over the South was ill-conceived.

For both sides, the war was going to be a very bloody affair.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments