By John J. Domagalski

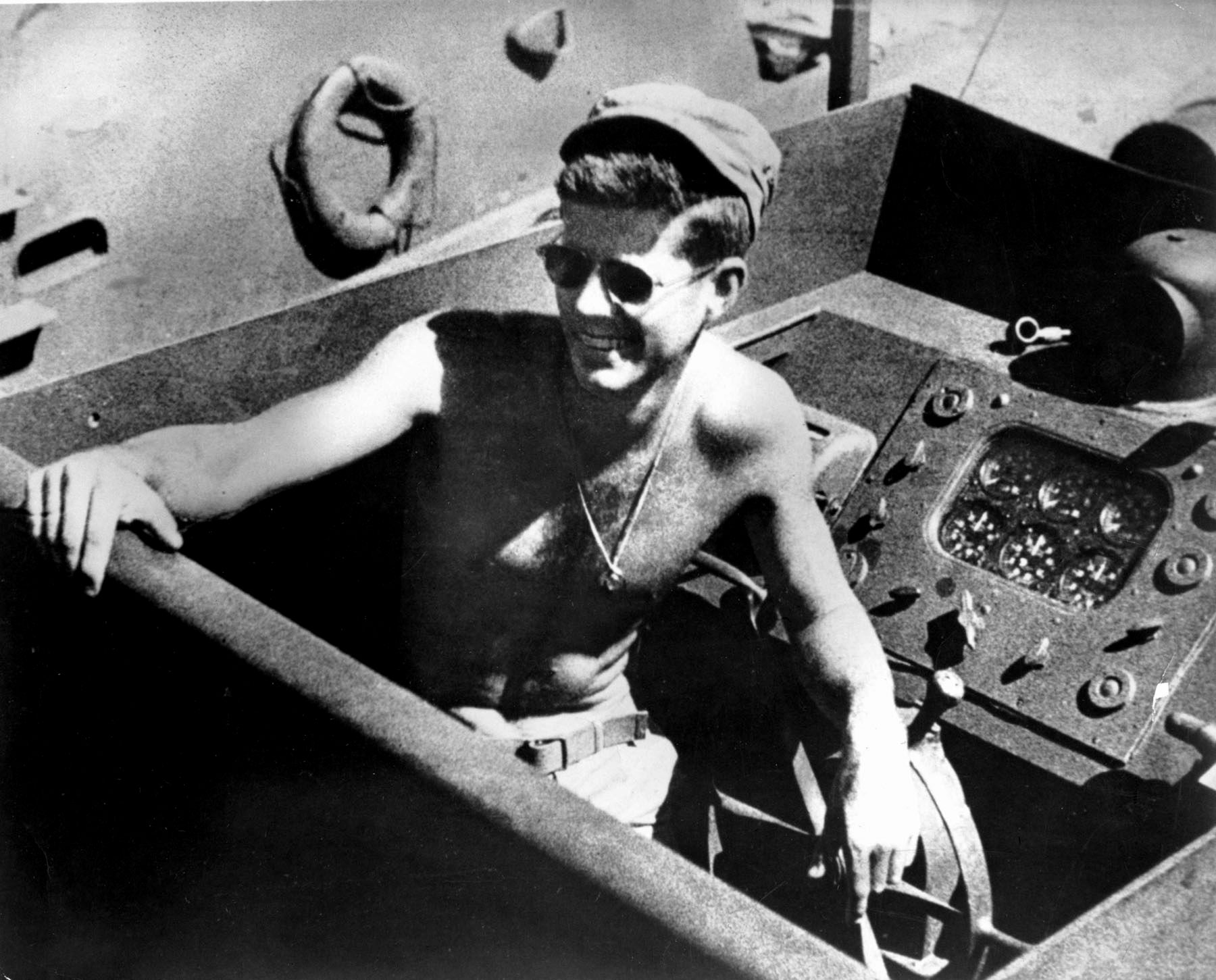

The celebrated life of President John F. Kennedy has been recounted many times in the decades since he assumed the highest office in the land. His time spent in the navy during World War II is lesser known to more recent generations. His service as a junior officer brought him close to death 80 years ago on the front lines of the war.

Lieutenant John Kennedy joined the front lines in the South Pacific as he pointed the bow of PT-109 toward the small PT boat base off Rendova Island. It was July 1943, in the Solomon Islands. His small patrol, torpedo or “PT” boat was about 80 feet long, made of wood, and armed with torpedoes and some light guns. Fierce fighting had been taking place on nearby New Georgia since the American invasion on June 30.

The road to war for the young officer had been a long one. The son of a former American ambassador to England was able to join the Navy through his father’s connections even with a bad back suffered while playing football at Harvard University. Kennedy was working a desk job at the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, D.C., when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He later volunteered for PT boat duty while attending officer training in Chicago.

The small kidney-shaped Lumbari Island, positioned near the entrance to Rendova Harbor, was serving as a forward operating base for torpedo boats under the command of Lieutenant Commander Thomas G. Warfield. The Rendova PT boats were under orders to intercept Japanese attempts to deliver reinforcements to New Georgia—voyages dubbed the “Tokyo Express”—and guard the area against enemy surface ships. The boats operated in the waters north and west of Rendova covering a distance of about 50 miles.

The geography was new to young Kennedy. The round island Kolombangara stood directly northwest of New Georgia. A narrow string of miniature islands ran along the southern boundaries of Kolombangara and adjacent Vella Gulf. Kennedy would soon become familiar with island names like Gizo and Wana Wana, the body of water called Blackett Strait off the southwest coast of Kolombangara, and narrow passageways such as Ferguson Passage. Kennedy and his men quickly fell into an exhaustive routine—tense night patrols, limited sleep, possible friendly fire incidents, and the nearly constant threat of enemy air attacks.

August 1, 1943, looked to be a routine day for the men aboard PT-109. She was scheduled to stay in base that night after recently completing several nocturnal patrols. The boats were increasingly encountering armored Japanese barges, prompting Kennedy to add some firepower to his PT in the form of an old army 37mm anti-tank gun. The single shot gun was mounted on some wooden planks near the bow of the boat. It was only an experiment, but Kennedy was comfortable knowing he would have some added firepower when he inevitably came across an enemy barge.

The situation changed that night when Warfield received a coded message from superiors warning a Tokyo Express run was planned and directing him to deploy the maximum number of PT boats. “Jap air out to get Peter Tars [PT Boats],” the message also advised. Warfield had little time to decipher the meaning of the ominous warning before the base was thrust into chaos.

A group of 18 Japanese bombers was suddenly approaching Lumbari Island—appearing so fast as to give the PT sailors little warning before the aircraft were almost overhead. John Kennedy jumped into action ordering PT-109 to get underway while briefly seeing a Japanese plane crash into the water off Rendova. His crewmen opened fire with the forward machine gun and 20mm cannon near the back of the boat.

The 109 was able to move out of harm’s way. Other boats, however, were not so lucky. Two PTs were considered total losses and two sailors killed. The harbor was a scene of chaos and destruction.

Warfield wasted no time in assessing the damage, developing an operational plan for the evening, and gathering his boat captains together for a meeting. Fifteen PT boats, including PT-109, were available for the operation. The plan divided the PTs into four separate groups, each including a radar-equipped boat. Three would be stationed near or in Blackett Strait, the most likely route of the Japanese destroyers. The remaining group was to be positioned further south as a reserve.

Warfield instructed his boat captains to restrict radio communications to contact reports. Individual boats were to follow their group leader to attack after hearing the initial sighting report. Further radio talk was likely discouraged to prevent interception by Japanese listeners and avoid confusion in the night conditions.

Kennedy’s PT-109 was assigned to a group of four boats under the command of Lieutenant Henry Brantingham in PT-159. The group was deployed the furthest north in Blackett Strait off the west side of Kolombangara. In addition to Kennedy and his executive officer, Ensign Lenny Thom, Ensign George Ross was aboard the boat as a third officer. Ross was a friend of Kennedy whose original boat had been damaged. Ten other enlisted sailors rounded out the crew.

When midnight ushered in August 2, 1943, PT-109 was slowly idling through Blackett Strait. The inky black moonless night coupled with the background of Kolombangara made for difficult conditions for even experienced sailors. John Kennedy was at the small bridge area known as the conn. The remaining crewmen were scattered around the boat. They were not at battle stations but ready to spring into action at a moment’s notice. Most were donning helmets and life jackets.

The sailors had no way of knowing the American intelligence was spot on—the Tokyo Express was running on this night. They also did not know the enemy mission was almost over. A group of Japanese destroyers had earlier sped through Blackett Strait carrying troops and supplies. Brantingham in PT-159, which had become separated from PT-109 in the dark conditions, spotted the enemy around midnight and closed in to attack without sending out a radio report. The fast-moving Japanese destroyers successfully dodged a bevy of American torpedoes before delivering their passengers and cargo to Vila on Kolombangara. The ships were now making a high-speed run back through Blackett Strait.

A cluster of sailors was around PT-109’s conn. Kennedy was manning the boat’s wheel. Radioman 2nd Class John Maguire was positioned to his right. Motor Machinist Mate 2nd Class Harold Marney manned the nearby .50-caliber machine gun. Lenny Thom was on Kennedy’s left side, just outside the conn. George Ross was acting as a lookout near the bow.

At about 2:30 a.m. an object suddenly appeared out of the dark night about 250 yards off the port bow and closing fast. “Ship at 2 o’clock,” Marney yelled. George Ross pointed out into the night at the approaching object. A 30- to 40-second sequence of terrifying events ensued. “At first I thought it was a PT,” Kennedy later said of the moment. “I think it was going at least 40 knots.”

The speeding warship was the Japanese destroyer Amagiri. Japanese lookouts spotted the torpedo boat only moments earlier. Whether the destroyer’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Kohei Hanami, turned his ship to ram or avoid the PT boat has been open to question during the decades since the event.

Kennedy glimpsed the phosphorescent wave from Amagiri’s bow. “As soon as I decided it was a destroyer, I turned to make a torpedo run,” he later recalled. Historians who reviewed PT-109’s final moments largely agree Kennedy had no more than 15 seconds to make a crucial decision. Before Kennedy could turn his boat for a torpedo attack, Amagiri’s steel hull crashed through the wooden PT hull.

The destroyer sliced into PT-109 at a sharp angle causing catastrophic damage. A brief burst of flames from the boat’s high-octane gasoline created a brilliant explosion while the air filled with the sound of cracking wood. One of the PT’s engines was knocked away as the boat was sliced in two beginning near the forward starboard side torpedo tube.

Kennedy was hurled against the wall of the conn, ending up on his bad back. “This is how it feels to be killed,” he thought during the moment. “I can best compare it to the onrushing trains in the old-time movies. They seemed to come right over you,” he later added. He glimpsed briefly at Amagiri’s slanted smokestack as the soaring warship passed. The destroyer quickly disappeared into the black night with her wake dousing the flames from the explosion.

Most of the sailors fell into the water or were knocked overboard by the force of the collision. Five of PT-109’s sailors were soon clinging to the still floating forward section of the boat—Kennedy, Thom, Seaman 1st Class Raymond Albert, Radioman 2nd Class John Maguire, and Quartermaster 3rd Class Edgar Mauer. Other sailors were scattered around the immediate area in the water. Kennedy initially ordered his small group to abandon ship over fears of a fire, but the men soon returned to the floating wreckage.

Kennedy began yelling out for his remaining men. Ross and five others replied. He swam out to help two injured men. Motor Machinist Mate 1st Class Patrick McMahon was stationed below deck and was badly burned. Kennedy towed him back with the strap of a life jacket while coaxing and berating injured Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Charles Harris along through the difficult swim.

Thom and Ross pulled aboard Motor Machinist Mate 2nd Class William Johnston, Torpedoman 2nd Class Ray Starkey, and Motor Machinist Mate 1st Class Gerard Zinser. The two remaining crewmen never responded to the calls. Torpedoman 2nd Class Andrew Kirksey and Motor Machinist Mate 2nd Class Harold Marney were both killed in the collision, possibly on impact.

The sailors took stock of their situation. The men knew they were in Japanese waters. McMahon was seriously hurt; others had less severe injuries or were affected by gasoline fumes, and all were exhausted.

The morning light of August 2 found the sailors’ situation deteriorating. There was no sign of any American PT-boat or seaplane. The wreckage, initially kept afloat by sealed compartments, was now taking on water. “We knew the ship would sink any minute, so we decided to swim for an island we knew was nearby,” Kennedy later said. They set out for a small island about three and a half miles away and hoped it was unoccupied.

Although Kennedy spent time on the Harvard swim team, nothing could have prepared him for what was ahead. He set out towing McMahon by clenching the life belt strap of the incapacitated sailor in his teeth. The remaining crewmen followed with two non-swimmers lashed to a wooden plank that was pulled or pushed along by the others.

Kennedy and McMahon made landfall on Plum Pudding Island after almost four hours of swimming. The exhausted Kennedy quickly collapsed. The others arrived a short time later after making the slow swim. The survivors had been in the water or on the wreckage for about 15 hours.

Plum Pudding was uninhabited and part of an assortment of small islands in Blackett Strait southeast of the larger Gizo Island. The islet was covered with trees, foliage, and low growth.

There was no substantial food or water—the coconut fruit on the trees was green and not edible. The sailors called it Bird Island due to the abundance of droppings.

A quick survey found no sign of the Japanese. However, it was clear they were not far when a slow-moving enemy barge passed nearby. The closest Japanese soldiers were on Gizo Island about 5 miles away.

A formation of planes overflew the island low and fast shortly after the sailors arrived. The men hid in the foliage thinking the aircraft were Japanese. They realized the planes were New Zealanders after spotting the white tails, though too late to try to send off a signal flare.

The planes were in fact looking for any sign of the missing PT sailors. It was clear to base commanders PT-109 was missing when she did not return to Lumbari. The morning briefing included some discussion about sending PTs out to search Blackett Strait. The idea was abandoned when other boat captains reported seeing the terrific explosion ripping apart the 109. The possibility of survivors did not seem likely. An air search was ordered. The New Zealand pilots spotted the wreckage with no one aboard and did not see the men hiding on the island.

“He was presumed to be dead,” fellow boat captain Richard Kersey later recalled of Kennedy. A simple funeral service was held at the base for the crew of PT-109. As is the case in war, PT boat operations then continued.

Kennedy knew they could not stay on the island and their position was not far from Ferguson Passage—the route taken by PT boats to enter Blackett Strait. He decided the best possibility of rescue was to swim out into the passage in the hopes of hailing a passing PT with a lantern salvaged from his sunken boat.

He set out in the early evening, island-hopping among several small islets and reefs, suffering some painful coral cuts to his feet along the journey. It was dark by the time he arrived in Ferguson Passage. Kennedy treaded water for about an hour while grasping the lantern and intently listening for the muffled sound of boat motors. At one point he sighted some flares far off in the distance beyond Gizo. The weary sailor eventually concluded the PTs were operating elsewhere.

The swim back to Plumb Pudding Island was difficult. Strong currents pushed him back and then out into Blackett Strait. He was chilled. The sailors back on the island were intently waiting—hoping their boat captain would return with news of finding a PT boat. They were disappointed.

Kennedy was thoroughly exhausted by the time he arrived back on the island. He spoke briefly to Ross, directing him to make the same attempt during the next evening. Kennedy then passed out and would sleep through the day. Ross spent the night perched on a small island overlooking Ferguson Passage armed with a signal pistol. There were no signs of any PT boats.

After the decision was made to leave Plum Pudding Island, the shipwrecked sailors were back in the water on August 4 heading south to the larger Olasana Island in the hopes of finding food and water as well as moving closer to Ferguson Passage. Kennedy and Ross had previously spotted the island and taken note of the abundant coconut trees. The boat captain again towed McMahon by the life belt strap, and the others grouped around the wooden plank for the three-hour swim.

The sailors found more coconuts on the new island with the juice giving some of the men a sick feeling. However, there was no sign of water, and they did not venture far from a small area over fear of encountering Japanese troops. Some of the men resorted to licking the water off leaves after an evening rain.

Morale among the group was low, and several viewed their situation as hopeless. Their ordeal was now stretched to four days with no sign of help. Kennedy met with Thom and Ross. “What do we do now?” he asked. Kennedy was not ready to give up. He decided to go with Ross to Nauru Island, the easternmost island in their vicinity overlooking Ferguson Passage. Both were tired and weak. The pair arrived around noon on August 5. Wary of possible Japanese patrols, the two peered from the brush to see a small enemy boat out on the reef. It appeared to be wrecked.

They spotted a small unopened box with Japanese markings near their position. It contained—to their delight—some candy. An additional find was a small shelter with a keg of water and a one-man canoe. Kennedy and Ross took a drink and were heading back toward the beach when they suddenly spotted two men on the Japanese wreck. They were most likely islanders and probably not Japanese. Kennedy called out, but the natives quickly paddled away in a canoe.

Kennedy used the newly found canoe for another evening trip into Ferguson Passage with the same results—no PT boats. After paddling back, he loaded the candy and water aboard before setting out to return to his men on Olasana. Ross remained on Naru to rest.

Arriving on Olasana, Kennedy was surprised to find the same two natives from Naru with his men. The two were Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana. Both were only 19 years old and working as scouts for the Allies. The men had stopped for coconuts on Olasana after their earlier encounter with Kennedy and Ross. Thom convinced them they were Americans by shouting, “White star! White star!” while pointing to the sky. The natives seemed to understand as they were taught to help downed American pilots whose planes were adorned with white star markings.

Gasa and Kumana accompanied Kennedy back to Naru, picking up Ross along the way when they encountered him swimming back to Olasana. Once on Naru they showed the Americans the location of a hidden two-man canoe. Thom had already written a note describing their position for the islanders to take to Allied authorities. Kennedy decided to add another, carving a message in a coconut husk with his knife: “11 alive native knows posit & reef Naru Island Kennedy.” He reportedly told them “Rendova, Rendova,” referencing the PT base.

Perhaps still suspicious of the final outcome or not wanting to leave anything to chance, Kennedy insisted on he and Ross using the two-man canoe to again venture out into Ferguson Passage on the night of August 6. It was a near fatal decision. They did not get far before heavy seas swamped the canoe, battering both men. The pair eventually made it back to the shallow waters around Naru suffering painful injuries from the sharp coral before getting on dry land.

Kennedy and Ross did now know that someone had actually been looking for the PT-109 men. Australian Sub-Lieutenant Reginald Evans overlooked Blackett Strait from a perch on Kolombangara. He was charged with reporting Japanese ship and plane movements to American authorities on Guadalcanal. Evans previously sighted a floating object in Blackett Strait but was not able to discern that it was wreckage from a PT and did not see any sailors. He dispatched natives to search for possible survivors after receiving a radio message about the missing PT-109 and later reported the searches were negative.

The exhausted Kennedy and Ross woke up the next morning to find four natives with them. One spoke English and produced a letter from coastwatcher Evans requesting the senior officer visit him by canoe on Gomu Island in Blackett Strait. The islanders first took Kennedy and Ross back to Olasana where they unpacked supplies. Some of the natives began cooking a meal on a portable stove, including beef hash, potatoes and c-rations. It was the first solid meal for the hungry sailors in days. Others constructed a lean-to shelter for the injured McMahon.

By afternoon it was time for Kennedy to make the trip to see Evans. He hid out of sight in a canoe under some carefully placed palm leaves as the islanders paddled across Blackett Strait. Evans ventured down to the beach after spotting the approaching canoe at about 6 p.m. “Hello, I’m Kennedy,” the American said after uncovering himself. “Come to my tent and have a cup of tea,” Evans replied.

Evans had already notified the Rendova PT base of the survivors. Navy officials were planning to send boats directly to the men on Olasana while Kennedy was directed to return to Rendova. Kennedy insisted on his personal involvement in the operation so the rescue boats could safely get through the shallow waters and reefs. The plan was modified—the boats would pick up Kennedy on small Patparan Island in Blackett Strait before completing the rescue of the others.

The seven PT boats participating in the rescue operation departed Rendova on the evening of August 7. Five went directly to a patrol area at the lower end of Vella Gulf, arriving by 9:30 p.m. Visibility was fair to poor with some cloud cover and rain. The actual rescue would be done by PT-157 under the command of Lieutenant William Liebenow with assistance from PT-171. Lieutenant Henry Brantingham was in overall command of the operation aboard PT-157. Others on the boat were a pharmacist mate, three natives—including Gasa and Kumana—Lieutenant Alvin Cluster, and two war correspondents in addition to the regular boat crew. The two boats traveled at a slow speed to Patparan Island so as not to attract the attention of any lurking Japanese float planes.

Kennedy left Evans’s hideout with some natives by canoe earlier in the evening for the voyage to the rendezvous point. They waited in the darkness at the 10 p.m. meeting time. The sound of rumbling motors more than an hour later marked the arrival of the rescue boats.

An exchange of shots in the air confirmed the identity of both sides before the canoe pulled up to the side of PT-157. Someone from the PT shouted, “Hey Jack.” Kennedy was still irritated over not being rescued after the sinking. He angrily responded, “Where the hell have you been?” The ill will quickly faded away after he was pulled aboard.

The two PTs headed for Olasana, arriving sometime after midnight. With PT-171 providing cover in the background, PT-157 slowly moved along the reef with Kennedy looking for an opening he knew was there. “[Kennedy] stood between me at the wheel, and the two natives,” Liebenow later wrote of the tense moments. “He pointed out the direction, the natives agreed, and we headed out.”

Kennedy joined Cluster and an islander in a small wooden boat lowered off the stern. The other PT-109 sailors were asleep when they came ashore. Kennedy called in the darkness for Thom, to the chagrin of the other rescuers who were concerned about possible nearby Japanese. “Here we are!” Thom finally answered. A second small boat was brought in to help. All of the shipwrecked sailors were soon aboard the rescue boat after several trips.

William Liebenow then set a course for Rendova. His crew provided all the possible comforts for the PT-109 men during the three-hour voyage—sandwiches and brandy were served, the pharmacist mate assisted the wounded, and reporters collected information for their stories. The PT arrived at Rendova at about 5 a.m. on August 8, ending the nearly week-long ordeal. The rescued sailors received a stirring welcome once ashore.

Kennedy convalesced for about a week with medical care for cuts, lacerations, and fatigue. He then moved to a tent for rest. Losing two crewmen weighed heavily on the boat captain. Kirksey had previously had a premonition of death. “When a fellow gets the feeling that he’s in for it, the only thing to do is to let him get off the boat because strangely enough, they always seem to be the ones that do get it,” Kennedy wrote at the time. “I don’t know whether it’s just coincidence or what. He had a wife and three kids. The other fellow had just come aboard. He was only a kid himself.”

John Kennedy remained in the Pacific until November 1943, commanding PT-59 for a time. He then returned to the United States and spent time at the Naval Hospital in Chelsea, Massachusetts. He was granted a medical discharge on December 27, 1944, with the Secretary of the Navy making it effective on March 16, 1945.

Kennedy was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his actions after the loss of PT-109. He also earned the Purple Heart for injuries sustained in the sinking. The story initially appeared in some newspapers and later gained a larger audience when reporter John Hersey published articles in The New Yorker and Reader’s Digest. Kennedy later campaigned as a war hero, entering politics and eventually becoming the 35th American President in 1961.

John J. Domagalski is the author of three books on World War II. Into the Dark Water: The Story of Three Officers and PT-109 (Casemate, 2014), Sunk in Kula Gulf (Potomac Books, 2012), and Lost at Guadalcanal (McFarland, 2010). His articles have appeared in WWII History, Naval History, and WWII Quarterly magazines. He is a graduate of Northern Illinois University and lives near Chicago.

Domalagski gave me very interesting details I have not previously seen. Jack was indeed a bonified war hero. I’m surprised he was not awarded a Medal of Honor.

FWIW, I think Jack’s murder in Dallas 19 years later snuffed what promised to be one of the most consequential Presidents in recent history. And had his brother, Bobbie been elected after Jack’s death there’s little doubt his too would have been a consquential time as POTUS.

Domalagski’s recounting of the PT109 sinking clearly described a man who had the leadership and command qualities for his later accent to the Whitehouse