Undeniably “war is hell,” but surely no war was more hellish for the common soldier thanWorld War I. The United States’ participation in the conflict, although of vital strategic benefit to our allies, was relatively brief, limited in scope, and overwhelmingly successful. It was, in effect, a positive experience for us as a nation. Thus how easy it is for Americans to forget that an entire generation of

French, German, and English youth were slaughtered, maimed, or psychologically scarred in the Great War of 1914-1918. The horrors of facism and of genocide, the carnage of World War II, and much of the uncertainty of our lives today were the bitter fruits of that “war to end all wars.”

For those whose expectations of warfare were rooted in 19th-century concepts of honor and glory, of martial trappings and patriotic duty, the reality of the Western Front proved an agony of unimaginable proportions. “It is like the eternal place of gnashing of teeth,” wrote doomed English poet Wilfred Owen; “the Slough of Despond could be contained in one of its crater-holes; the fires of Sodom and Gomorrah could not light a candle to it … everything unnatural, broken, blasted….” It was, Owen thought, a place “where death becomes absurd and life absurder.”

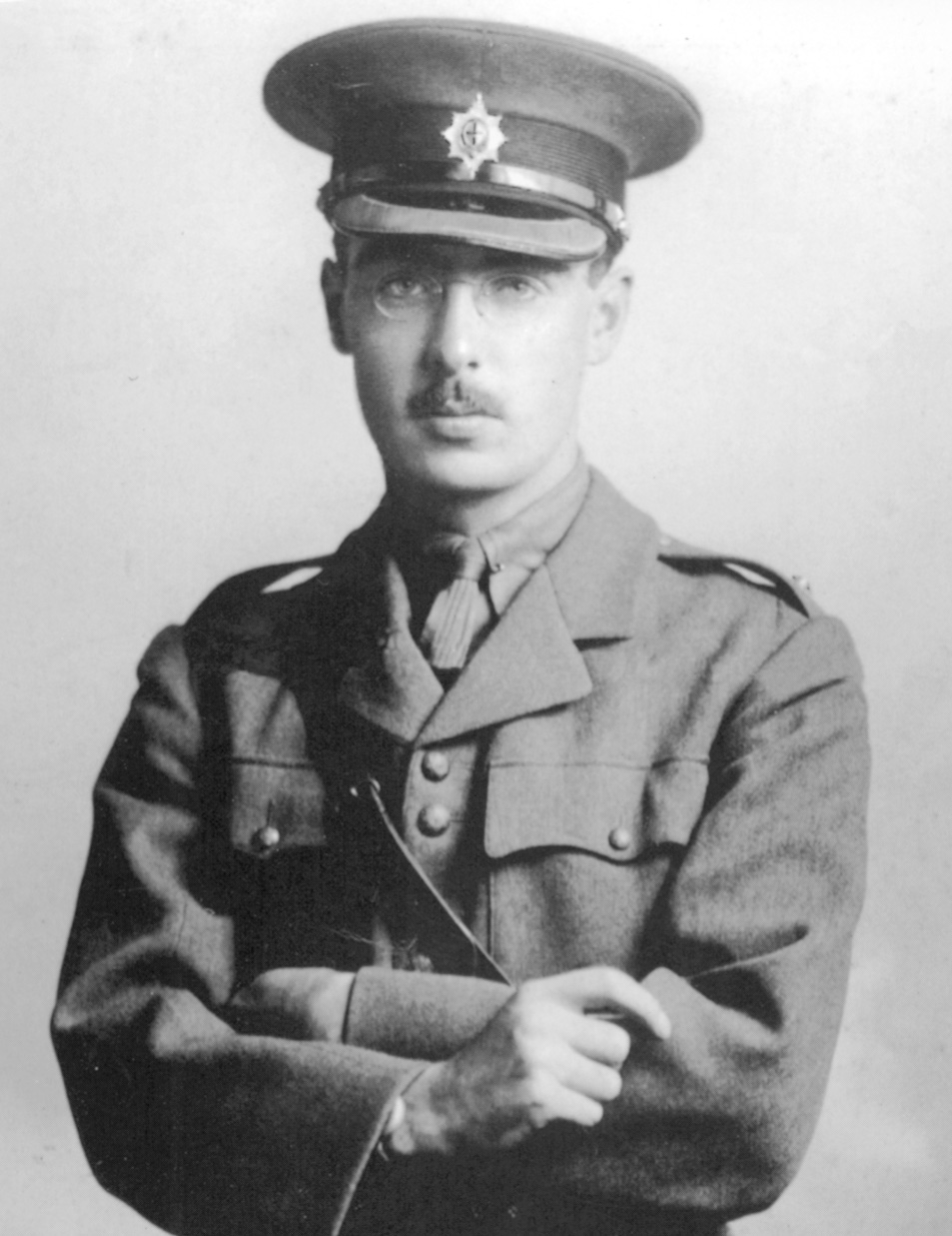

Reading the published recollections of those who endured that hellish conflict—authors like the German Ernst Junger, the Frenchman Maurice Genevoix, and English veterans Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, Edmund Blunden, and Edwin Vaughan, to name a few—one wonders from the comfort of one’s armchair, how did they do it? How did they hold themselves together mentally, spiritually, amid the constant presence of violent death and obliteration that was surreal in its horror? Have You Forgotten Yet? The First World War Memoirs of C.P. Blacker (John Blacker, ed., Leo Cooper, Pen & Sword Books Ltd., Yorkshire, England, 2000, 321 pp., maps, illustrations, appendices, index; U.S. distributor Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, $36.95 hardcover) is an insightful and profoundly eloquent addition to the literature of the First World War. Drawing from his wartime diaries and almost daily letters home, Blacker began what he always referred to as his “autobiography” in 1963. John Blacker, who compiled this volume from his late father’s 900-page typescript, notes the remark made by one of his father’s medical colleagues who upon reading the manuscript said, “It’s not an autobiography; it’s a catharsis.” In revisiting memories that he likely preferred to forget, C.P. Blacker was in a sense “cleansing” his psyche of the dark shadow of a war he considered a “hideous mistake” from the outset.

Blacker’s disinclination to give way to the war fever that swept across Europe in August 1914 had much to do with his upbringing. His father, also named Carlos Paton Blacker, was of mixed English and Spanish descent; he was a world traveler with a passionate fondness for art and literature whose friends included Oscar Wilde, Anatole France, and George Bernard Shaw. C.P. Blacker’s mother, Caroline, was an American, the daughter of former Confederate General Daniel Frost. His parents “were not typically British,” Blacker writes.“They did not try to assume the Anglo-Saxon’s undemonstrative and phlegmatic façade behind which feelings were concealed.”

Blacker’s disinclination to give way to the war fever that swept across Europe in August 1914 had much to do with his upbringing. His father, also named Carlos Paton Blacker, was of mixed English and Spanish descent; he was a world traveler with a passionate fondness for art and literature whose friends included Oscar Wilde, Anatole France, and George Bernard Shaw. C.P. Blacker’s mother, Caroline, was an American, the daughter of former Confederate General Daniel Frost. His parents “were not typically British,” Blacker writes.“They did not try to assume the Anglo-Saxon’s undemonstrative and phlegmatic façade behind which feelings were concealed.”

What he wrote of them he might equally have written of himself. Noting their “strong literary tastes,” he remarks, “Such people live more in their imaginations than do people with exclusively vocational interests or those for whom books are no more than oblong objects you see on shelves.”

Born in Paris in 1895, much of C.P. Blacker’s childhood was spent abroad—some of the happiest years in Germany, a country his father considered a sort of spiritual home. His paternal aunt was married to a German and one of young Blacker’s cousins would later serve as an officer in the Kaiser’s army. “I never overcame those early sentiments to the point of hating and wanting to kill Germans,” Blacker writes. “I had no wish to kill Germans or anyone else … I always had a deep respect for the genuine conscientious objector.” That ambivalence, combined with poor eyesight and a desire to pursue the study of zoology at Oxford, postponed his involvement in the escalating conflict until February of 1915, when he tendered his services as a civilian volunteer with the British Field Hospital for Belgium. He came to view the five months he spent caring for the mangled victims of modern warfare as “a sort of inoculation” for what was to come.

In the summer of 1915 C.P. Blacker and his younger brother Robin entered the officer corps of one of Britain’s proudest regiments, the Coldstream Guards. On August 26 Robin Blacker embarked for France where he joined the 1st Battalion. Just over a month later, on September 28, he disappeared in the shambles of a failed assault at Loos. His body was recovered on October 14, eight days after C.P. Blacker had arrived for duty with the Coldstreams’ 4th Battalion—a unit detailed for duty as Pioneers, who constructed and maintained the ever-expanding labyrinth of trenches that scarred the landscape of southwest Belgium and northern France. He served with the Pioneers until the summer of 1918, when he transferred to his regiment’s 2nd Battalion and was wounded while commanding a company in the final Allied offensive.

Blacker’s memoir is replete with descriptive characterizations of his fellow soldiers. His first company commander was a Boer War veteran with “a bushy moustache, a stoop, mumbling speech, and a way of peering about, half mystified, half apprehensive….” One stalwart sergeant is described as “an effective disciplinarian with a rough tongue,” who “had a low gritty word of command … it was seemingly with a rictus of contempt that he would call the platoon to attention.” A group of German prisoners being hustled to the rear “were physically small men who were chattering like monkeys. They looked like green gnomes, their uniforms surprisingly clean.” These remarkably observant and well-crafted word pictures are a testimony to Blacker’s considerable literary skills, and bring to life those who might otherwise be mere names on a military roster.

The hardships and horrors of war receive equally vivid coverage. Digging a mine beneath the German lines through a low tunnel, claustrophobic and pooled with water, Blacker moves painfully “with bent legs and body upright, like an anthropoid ape.” While working in mud that turned the trenches into a “degenerating swamp” it might take 10 minutes to fill a single sandbag. “The glutinous clay stuck to your shovel so that you had to push it into the sandbag with your hands,” Blacker writes. In winter the mud froze “to the consistency of rock,” so that an exploding shell turned the frigid soil into razor sharp shards.

The hardships and horrors of war receive equally vivid coverage. Digging a mine beneath the German lines through a low tunnel, claustrophobic and pooled with water, Blacker moves painfully “with bent legs and body upright, like an anthropoid ape.” While working in mud that turned the trenches into a “degenerating swamp” it might take 10 minutes to fill a single sandbag. “The glutinous clay stuck to your shovel so that you had to push it into the sandbag with your hands,” Blacker writes. In winter the mud froze “to the consistency of rock,” so that an exploding shell turned the frigid soil into razor sharp shards.

The “annihilating stench” of the dead was ever-present, “the manifold smells of putrefaction, each more nauseous than the last,” as bodies were blown out of their shallow graves, or unearthed during the construction of new trenches.

The front was a place of “latent menace,” where one could, at any time, be torn to pieces by a shell fired from “beyond the range of your vision.” The very landscape was malevolent, pockmarked with craters and strewn with the shambles of humanity. “The quiescent battlefield was like a monster that was pretending to be asleep,” Blacker thought. “In its own time it would wake up and savagely retaliate. It understood exactly what was happening, and it had a long memory.”

In one of many powerful descriptions of his ordeal under fire, Blacker recalls an intense German bombardment: “The air went taut in a tidal wave of sound … it seemed that everything round you was spouting noise—the blasted trees, the iron pickets, the barbed wire, the very earth. The air seemed to go solid with it, stiffening and rounding your back. Your senses were pressed down into a lower plane of consciousness. Standing like mutes, we communicated by sign-language and gesture.” He witnessed the brutal deaths of his friends and of his soldiers, and spares no ghastly detail, as when the “savage, rending thump” of an explosion blew one man’s face off, leaving him a “groping, sightless figure, kneeling and pawing the air.”

Given his lack of patriotic fervor and militant jingoism, that Blacker was able to maintain his psychological equilibrium amid the hell of war, and conduct himself with the determined military demeanor expected of a Guards officer, had everything to do with the spiritual and intellectual makeup of the man. He was a devotee of classical music, of literature and philosophy, listening to opera on a dugout gramophone, or reading a volume on Indian religions during a bombardment. But above it was his love of nature that sustained him. He found beauty in the wildflowers that carpeted no-man’s-land in the springtime, and recorded the species of birds that fluttered and sang above the wasteland. It was a way of holding on to what was timeless and sane.

One of the most moving sections of Blacker’s autobiography describes the weeks he spent in command of a detachment assigned to harvest wood for military construction from the forest of Clairmarais. It was an idyllic respite from the trenches, and the young officer found a special place along a logging trail deep within the forest where, on his hours off duty, he would sit alone and “reflect on the past, the present, and the impending future.” The memory of Clairmarais was a solace, a spiritual touchstone. “I recall,” he writes, “how in several anguishing situations during the following September [on the Somme], the thought came, like a hand on my shoulder: think of your roadside: think of your forest.” Cherishing those interludes of tranquility, and contemplating with “wonder, awe and gratitude” the infinite grandeur of the starlit heavens, Blacker felt that he had received “a gift of grace which would immunize against fear and failure of nerve.”

Beautifully written and powerfully told, Have You Forgotten Yet? deserves to be ranked among the classic narratives of the First World War.

Brian C. Pohanka

The Cat from Hué: A Vietnam War Story, by John Laurence, Public Affairs, NYC, 2002, 850 pp., $30.00 hardcover

The Cat from Hué: A Vietnam War Story, by John Laurence, Public Affairs, NYC, 2002, 850 pp., $30.00 hardcover

John Laurence arrived in Vietnam in 1965. He was 25 years old and a newly minted combat reporter for CBS Television News. Like most Americans, both military and civilian, he believed that the war was just and that U.S. military power would be triumphant. By 1968 and the Battle of Hué, his disillusionment was complete and he viewed the war as a gigantic killing machine.

The book opens with the Battle of Hué. By 1968 Laurence had witnessed numerous battles, risked life and limb, and seen the failure of the Americanization of the Vietnamese. The Battle of Hué was fought in the city among the ruins of bombed-out buildings. The Americans were up against an enemy that would not give up, no matter the cost, and suffered great loss of life with little gain in territory. “Each day the Marines advanced a few more meters across the burned ground and each day the two sides sent back another load of battle dead.” Laurence himself was due to be shipped out of Vietnam and found that he was the victim of short-timers’ syndrome. In the midst of this chaos and death, he rescues a kitten who seems to hate Americans. Laurence attempts to befriend him by feeding him, with little success. At the last moment before leaving Hué he takes the kitten with him. The story of the “cat from Hué” runs throughout the book and throughout Lawrence’s life after Vietnam.

Laurence covers his tour of duty in Vietnam in great detail and with eloquent language. He describes his initiation into the brotherhood of combat reporters and photographers as being similar to a soldier’s becoming part of his military unit. At first Laurence is shunned by press who had been in the country for a longer period of time. A new arrival was not accepted until he had witnessed the fighting at close range. In spite of the camaraderie, there was a great deal of rivalry among the news services and television networks. There was pressure to get the story first and to get the film out of the field to Saigon, where it could be sent home for broadcast. And there was a necessity to “play ball” with the military to get an interview, a story, or transportation to the action.

The Cat from Hué shines most brightly when Laurence recalls his conversations with American

soldiers and Marines. “Our first loyalty was to the American public to be truthful, then to the Marines we accompanied to be fair, then to CBS News to be competitive and hard-working.” He also focuses on the Vietnamese civilians, who having witnessed decades of occupation by foreign powers, chose to either “wait patiently for it to pass or join the resistance and fight.”

It took John Laurence decades to come to terms with his memories of and experiences in Vietnam. He drew on his own extensive notes and hundreds of hours of film footage shot at the time to create a compelling, informative, and memorable read. The Cat from Hué is a valuable addition to the numerous books that have been written on the Vietnam War.

Laura Cleveland

Battles That Changed History by Geoffrey Regan, Carlton Books, London, England, 2002, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, $27.95 hardcover

Battles That Changed History by Geoffrey Regan, Carlton Books, London, England, 2002, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, $27.95 hardcover

It is a well-known and unfortunate fact that human history is military history; nations rise and fall on pivotal battles, great political leaders were often once great military leaders, and the technologies that benefit our lives now were probably, at some point, on the cutting edge of martial science.

It is perhaps with this thought in mind that Geoffrey Regan has assembled Battles That Changed History. Regan’s book offers us a look at 50 battles that span from the time of Phillip of Macedon to the Gulf War, each one a significant turning point in the history of humankind. Each chapter covers a battle in five to six pages, complete with illustrations and (best of all) maps.

It seems to me that one or two major battles may have been left out; gone, for example, is the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, where Constantine I would win the title of Emperor of the Romans and steer the Empire in a decidedly Christian direction. And while the Battle of Gettysburg is present, the Battle of Manassas, the first sign of true trouble in the American Civil War, is curiously absent. This, in truth, cannot be faulted to Mr. Regan; 50 battles is too small a count to do justice to the subject. Still, Regan has done a splendid job, and his descriptions are not only excellent dissections of the battles themselves, but food for thought as to what forces have shaped human history, and what forces may do it again.

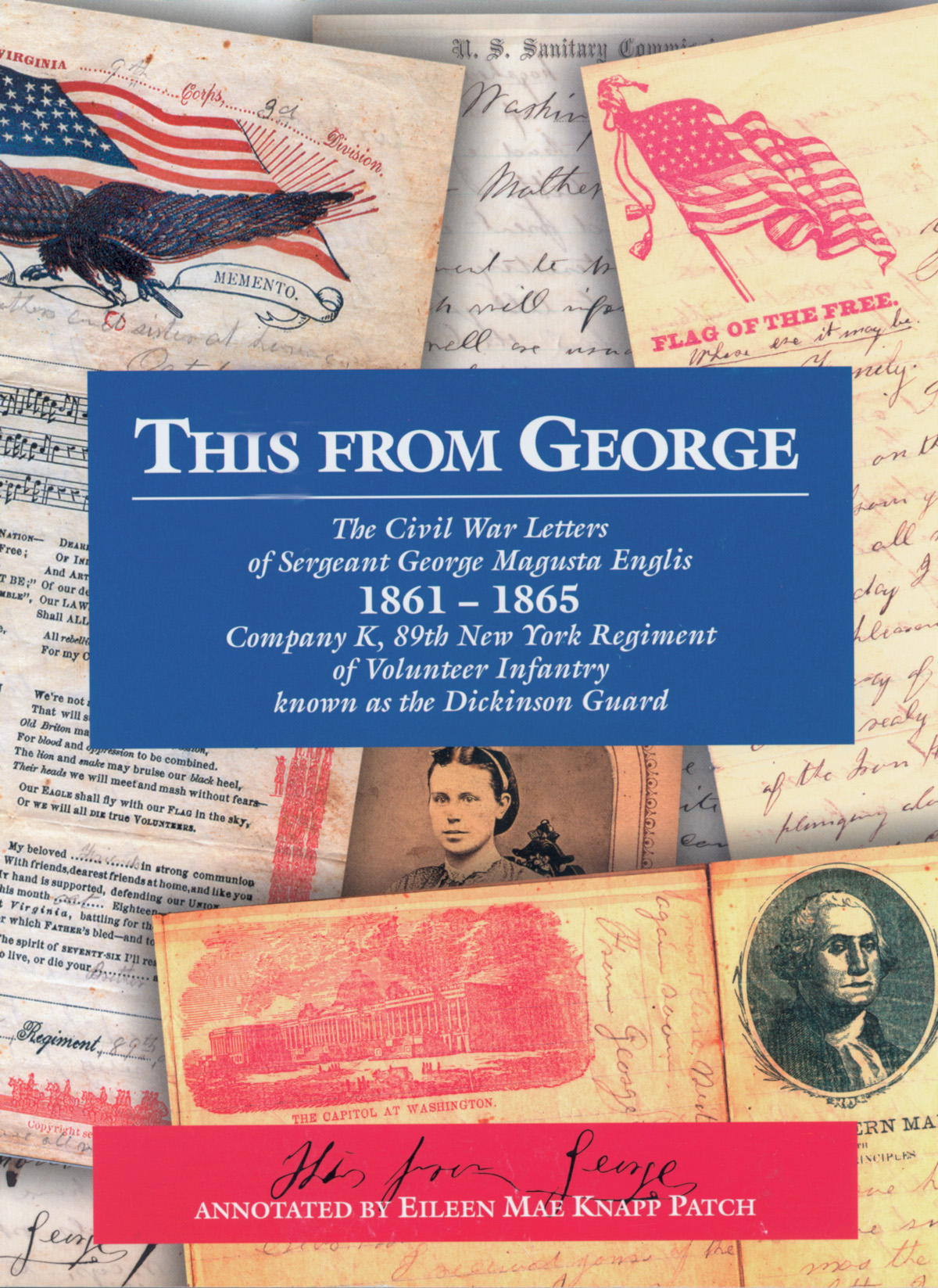

This from George by Eileen Mae Knapp Patch (ed.), Broome County Historical Society, Binghamton, NY, 2001, 288 pp., photographs, maps, appendices, $25.00 softcover

This from George by Eileen Mae Knapp Patch (ed.), Broome County Historical Society, Binghamton, NY, 2001, 288 pp., photographs, maps, appendices, $25.00 softcover

Although politicians make military policy, and generals form strategies and tactics, it is soldiers who truly take the field and wage war. These are the men whose experience with battle is the purest, and it is through their recollections that we may form a more perfect vision of how war really works.

This from George is a collection of letters written by Sergeant George Magusta Englis, a member of the 89th New York Regiment during the American Civil War. Annotated by Sergeant Englis’s grand-niece, the letters follow Englis’s participation in the war, from his beginnings in boot camp (or “camp of instruction” as it was referred to) to the final Federal victory at Appomattox. The letters have been transcribed as they originally appeared, misspellings and all, and each missive is followed by an extensive annotation regarding the state of the war at that time, as well as the part that Sergeant Englis and his unit were playing in it.

In addition to the maps and photographs that appear throughout the book, the appendices contain copies of several of the letters, as well as enlistment papers, receipts and newspaper articles. Family trees are also provided that help the reader more firmly grasp the relationships between Englis and those he was writing to.

George Englis’s letters are a fascinating look into the world of the common soldier and are in every way as important as the memoirs of any general or admiral from that time period. They help us to better understand the men who truly fight our wars.

Jim Stutz

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments