By Al Hemingway

Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith was 62 years of age. At a time in life when most men contemplate retirement, he was a very busy individual. He was the top Marine in the Pacific and, despite his grandfatherly appearance, he had a tremendous temper. This earned him the nickname of “Howlin’ Mad.” After 40 years as a Marine, this would be Smith’s last assignment, but it would not be easy.

In October 1944, Smith received a message from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, informing him of the target for the next invasion of a Japanese-held Pacific island: Iwo Jima. It was given the code name Operation Detachment, but for those that fought there, it was simply called Iwo.

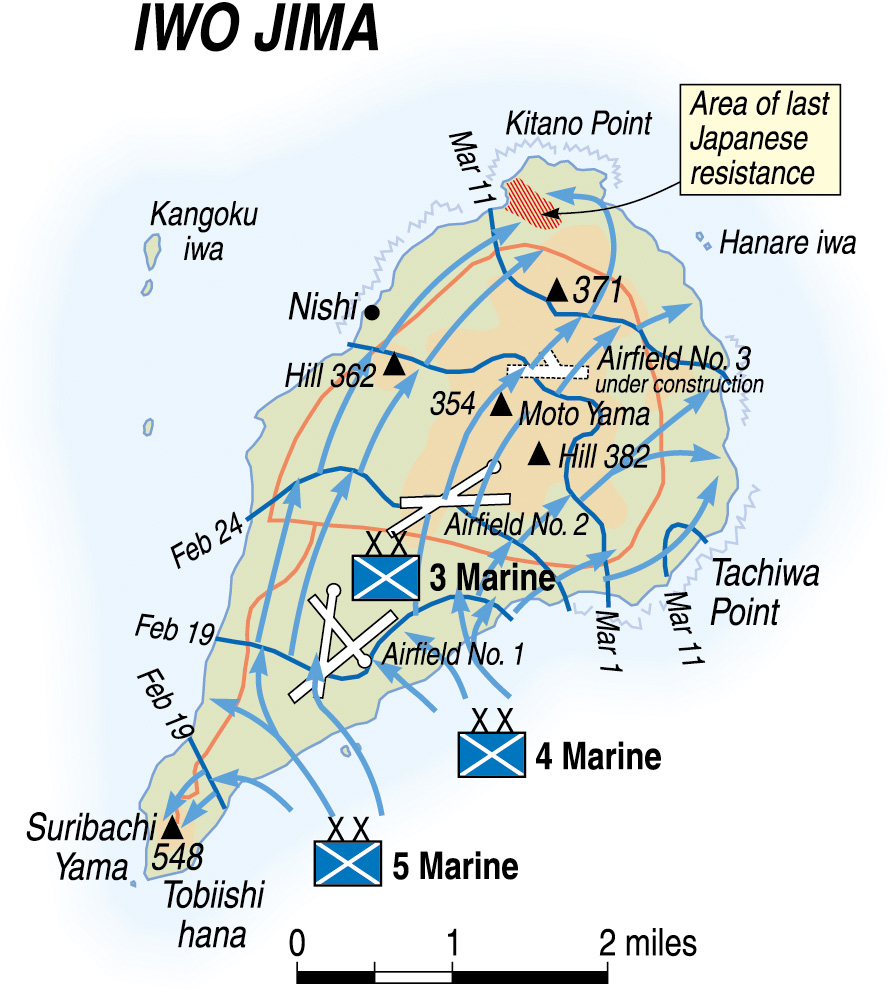

Smith ordered Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, commanding general of the Fifth Marine Amphibious Corps (VAC), to begin planning for the assault. Schmidt would use his 4th and 5th Marine-divisions which were training in Hawaii, in the initial attack. The 4th Division was led by Maj. Gen. Clifton B. Cates and the 5th by Maj. Gen. Keller E. Rockey. The 3rd Marine Division, headed by Maj. Gen. Graves B. Erskine, was involved in mopping-up operations on Guam and was corps reserve.

Iwo Jima needed to be seized if the Allies were to be victorious against the Japanese empire. That summer, General henry A. “Hap” Arnold of the Army Air Corps quickly grasped its importance. The new B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers could carry twice the bomb load of the older B-17 Flying Fortresses and had a range of over 3,000 miles, compared to the B-17’s 2,400. Arnold was anxious to strike at Japan with the B-29s, but he needed an emergency airfield for the crippled aircraft returning from bombing runs over Japan. Iwo Jima would be the most likely place. Arnold drew a line from the Marianas to Japan—it ran through Iwo.

From the air, Iwo Jima resembled a pork chop. Slightly less than eight square miles in size, it was five miles long and two and a half miles at its widest point. It was a barren land and until the outbreak of World War II had very few inhabitants. From the beaches to Moto Yama Plateau, located near the center of the island, the soil was nothing but ash and cinder. Northward, it was comprised of a yellowish clay-like substance, which was not conducive to any agricultural endeavors. The island’s mainstay was a sulphur refinery, that produced a strong, overpowering rotten egg odor. Hence, Iwo Jima was also referred to as Sulphur Island.

Iwo Jima had become part of the Japanese Empire in 1891. It is located in the Nanpo Shoto chain, a string of islands created by active volcanoes that had risen from the ocean thousands of years before. After the fall of Saipan, Tokyo realized the importance of Iwo Jima and fortified the island with troops and supplies to resist the inevitable invasion.

Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, a bright, innovative leader, was selected to command this crucial post. He had roughly 21,000 men on the tiny island. His units consisted of the 109th Division, the 145th Regiment, 17th Independent Mixed Regiment, 26th Tank Regiment, 2nd Mixed Brigade, the brigade artillery group, plus other machine gun and rocket companies and naval personnel.

Kuribayashi was disappointed upon his arrival to discover that the island’s defenses were in complete disarray. He chose a different strategy to repel the landing. He disregarded the traditional banzai charges and instead decided to dig tunnels, gun emplacements, observation posts, and supply dumps—even hospitals—completely underground. He would let the assault waves land, advance inland a few hundred yards, and hit them with everything he had.

In the north, heavy artillery was sited in a horseshoe configuration consisting of two 6-inch guns commandeered off a cruiser, 10 13mm machine guns, and 10 25mm antiaircraft guns. It was dubbed the Heavenly Mountain Battery.

Rocket guns, recently invented, arrived in the summer. There were two sizes: an 8-inch round launched from a barrel that could be rapidly disassembled and moved to another location, and a 16-inch round that was fired from a wooden chute. They had ranges of 2,000 yards and 3,000 yards, respectively.

In July 1944, six more 75mm mountain guns were positioned around Hill 362A in the northwest section. Also, several 47mm cannon were positioned in the area. Sniper holes, machine guns, and automatic weapons were situated in the caves, gullies, ravines, and gorges that dotted Iwo’s northern ground.

At Kitano Point, the extreme northern part of the island, Kuribayashi made his headquarters. It was an engineering masterpiece. A maze of tunneling ran 500 feet in all directions. His planning and strategy rooms were built 75 feet underground. The only structure above ground was the communication blockhouse, 150 feet in length and 70 feet wide, with its walls and ceiling fabricated from reinforced concrete five to 10 feet thick.

Nearer the center of the island, the Japanese erected another communication center to coordinate and control all the artillery fire. On the plateau, extra artillery and field pieces would cover the beaches where the Marines would come ashore. In all, there were an amazing 26 miles of passageways on Iwo Jima.

At the southern end of Iwo Jima loomed the 554-foot-high inactive volcano known as Mount Suribachi. It bristled with every weapon in the enemy’s arsenal and had seven stories of caves and tunnels. All of these were braced with any available material that could be confiscated: logs, driftwood, and even parts of damaged aircraft. Near the volcano, the Korean laborers could work for only 15 minutes at a time due to the incessant heat and sulphur fumes. Many of the compartments had electricity, water, and numerous entrances built to escape the flamethrowers the leathernecks would certainly employ against them. Cave openings were angled at 90 degrees to further frustrate the attackers. All the living quarters were vented to allow the sulphur fumes and steam to dissipate into the atmosphere. Every acre of Iwo Jima had been transformed into a killing zone.

By the beginning of February 1945, Iwo’s fortifications were nearly finished. As the time neared for the invasion, Kuribayashi knew that, even with his formidable defenses, he could not win. He was determined, however, to make the Marines pay with their blood for every yard of Japanese soil they took.

The naval and Marine forces assembled for the invasion were on a scale unprecedented thus far in the Pacific conflict. Nearly 800 warships would be used. Among these were eight battleships, 12 aircraft carriers, 19 cruisers, 44 destroyers, plus transports, LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank), LSMs (Landing Ship, Mechanized), and cargo and auxiliary vessels of all types. The Marines numbered over 70,000; add to that the Navy and U.S. Army personnel and the force totaled over 100,000 troops.

Strategic planning for the conquest of Iwo Jima proceeded smoothly until October 24, 1944, when a serious rift developed between the Marine Corps and Navy concerning pre-invasion bombardment. Schmidt wanted 10 days, using three battleships and assorted cruisers. This request went to Admiral Richmond K. Turner, commander of Task Force 51. It was denied. Turner felt they would lose the element of surprise with such a prolonged shelling and wanted just three days. This was ludicrous. The Japanese knew full well that a large invasion force was steaming toward Iwo Jima.

On November 8, 1944, another request was submitted, this time asking for nine days of bombardment. It was also rejected. The original plan, calling for three days, would stand. In fact, the Navy was planning to attack Japan with the might of Task Force 58 during the Iwo campaign mainly to offset all the publicity the Army Air Force’s B-29s were receiving. The Navy wanted to demonstrate that its carrier-based planes were as potent as the much-publicized bombers.

“Howlin’ Mad” was furious. He did not want any interservice rivalry to cause any serious hardships on his men. He took the argument all the way to Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, overall commander of the operation. This time the Marines requested just four days, but they were turned down again. Smith was heartbroken. He could not forget the bodies of hundreds of Marines floating in the lagoon at Tarawa in November 1943. These men, in his opinion, had died needlessly because naval gunfire had not neutralized the enemy defenses as planned. Years later, noted Marine historian Colonel Robert Heinl would write that canceling the additional shelling of Iwo Jima was a “costly irony.” The leathernecks would have to make do with three days.

Schmidt opted for the eastern beaches as the landing sites. The western approaches were discussed and initially approved, but the Navy did not like the surf conditions on that side of the island. The Marines reluctantly agreed, even though this gave the Japanese excellent fields of fire on the landing craft carrying the assault troops to the beaches. Each landing zone was divided into 500-yard sections totaling 3,000 yards.

The 1st and 2nd battalions, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division would land on Green Beach nearest Mount Suribachi. Next, on Red 1 and 2, the 1st and 2nd battalions, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division would hit the beach and seize Moto Yama Airfield No. 1. On Yellow 1 and 2, the 1st and 2nd battalions, 23rd Marines, 4th Marine Division would wheel right and strike at Moto Yama Airfield No. 2. Lastly, the 1st and 3rd battalions, 25th Marines, 4th Marine Division would take a sharp right after landing and move against the Quarry. The remaining battalions and the 3rd Marine Division would be held in reserve.

As the assault teams steamed toward their objective, Admiral William R.P. Blandy and his Task Force 52 had already commenced the three-day preliminary bombing of Iwo Jima. Simultaneously, just 60 miles off the coast of Japan Admiral Marc Mitscher’s task force was launching a carrier strike. Blandy’s armada of six battleships and five cruisers began its careful, methodical firing at predetermined targets. At day’s end, the fleet withdrew out to sea, with disappointing results. The overcast skies had proved detrimental to their shelling.

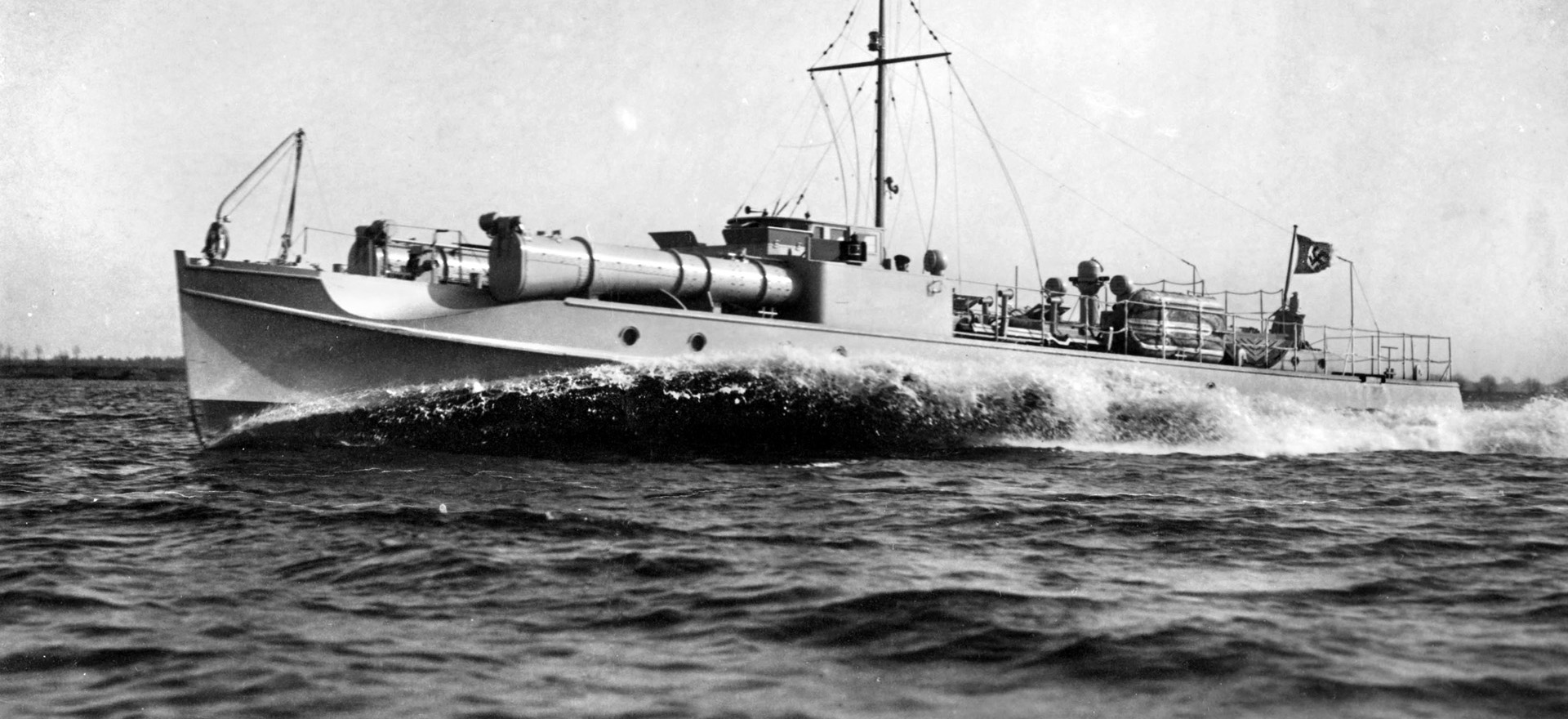

The following morning the UDTs (Underwater Demolition Teams) went into action. The frogmen were given the dangerous task of removing any mines or other obstructions that might hinder the landing. LCIs (Landing Craft, Infantry) had been outfitted with 20mm and 40mm cannon to provide cover for the UDT teams. As the spunky vessels came close to shore, the Japanese opened fire on them. Dropping off the frogmen, the tiny boats zigzagged trying to avoid the enemy gunners. Of the 12 ships involved, all were struck by artillery, with nine of them totally destroyed. When it was over, 43 were killed and 109 had been wounded from the LCIs, plus another seven killed and 33 wounded off one of the destroyers. The second day of the bombing was over, and the beaches were declared suitable for landing. The Japanese had drawn first blood.

On the last day of bombing, the primary targets were the base of Suribachi and artillery that protected the avenues of approach. From 7:45 am until 6:30 that evening the big guns blasted the tiny island. The Navy was optimistic at day’s end and estimated they had destroyed or damaged half of Iwo’s fortifications. The northern area was barely touched.

Admiral Blandy radioed Admiral Turner to report that his mission was complete and said another day of bombing would be fruitless. The Navy had completed its job. Now it was up to the Marines.

Dawn on Monday, February 19, 1945, saw the murky, gray skies over Iwo Jima change to an azure blue. The Marines stood, combat loaded, on the decks of the various transports, waiting to board their landing craft. The temperature was a pleasant 70 degrees, the sea was relatively calm, and a slight breeze was blowing. It was a perfect day for an invasion.

At 6:40 am, the pre H-hour bombardment commenced. Five battleships on the east coast and two on the west fired 75 rounds each in 80 minutes. Iwo rocked from the concussions of the 16-inch salvos. Four heavy cruisers and three light cruisers hurled 100 rounds of 8-inch shells and the destroyers fired their 5-inch rounds as well.

Although the bombardment was an awesome sight, many veterans from previous campaigns knew the Japanese would be waiting. As they prepared to go over the gunwales into the awaiting landing craft, the chaplain asked for a moment of silence and recited the 23rd Psalm. As they started their descent, Corpsman Greg Emery, attached to the 28th Marines, wished he had chosen something a little more uplifting. The part about the “valley of death” upset him.

Other Marines were to make the assault on the LVTs (amphibious tractors). As they climbed down the narrow metal ladders below deck, the Navy coxswains who guided the vessels to shore started the engines. Soon, the hold of the ship was filled with the sickening smell of the fumes emitted by the craft.

The line of departure was established several miles offshore. Shortly after 8 am, an air strike composed of 120 carrier planes soared overhead in two columns, dropping napalm on their first run. The jelly and gasoline mixture erupted, creating great billowing clouds of fire and intense heat that brought a loud chorus of cheers from the Marines. The aircraft soon returned with orders to “scrape their bellies on the beach” as they pounded the sandy coastline with strafing runs and rocket fire. When the fighters finished, the fleet resumed its bombardment. In total, the Navy fired over 8,000 rounds at Iwo Jima.

Just past 8:30 am, the main control ship dropped her pennant. The LCIs manned with rockets were followed closely by 68 LVTs mounted with 75mm howitzers. The vessels began their mad dash to the beachhead. The rocket boats launched 20,000 projectiles then swerved to the right and left to allow the amphibious tractors to get to the beach. Just before 9 am, the naval gunners began zeroing in their weapons on inland targets in a rolling barrage. When it was over, more fighters flew in, dropping their loads and peeling off over the sea. At 8:59 am, the first Marine touched ground on Red Beach 1. Americans had set foot on Japanese soil.

In rapid succession, the remaining waves churned ashore and headed for the wave-cut terraces that loomed ahead of them. These terraces, three in all and one right after the other, were caused by severe storms several years earlier that had pushed the loose ash into 10- to 15-foot piles. They stretched from the shore to the plateau where Airfield No. 1 was located.

Infantrymen soon discovered how taxing it was to maneuver in the volcanic ash. Pfc. Fred Walcsak, a mortarman from Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, was exhausted carrying the excessive weight from the weapon and the extra rounds. As he sunk ankle deep in the loose soil, he muttered to himself, “Goddamn this ash! Goddamn this ash!”

Enemy activity in the first half hour ashore had been surprising light. An occasional mortar round and some sporadic automatic weapons fire had been the extent of the resistance. That, however, was about to change.

Suddenly, the Japanese sprung to life. They had allowed the Marines to become crowded on the beaches before beginning their attack. From atop Suribachi and from the north, artillery and mortars cascaded on the Marines. It was impossible to make any type of tactical move—there just wasn’t any room. The only course of action was to move forward. According to one participant. “Front lines? There aren’t any goddamn front lines. This whole island is a front line.”

By late morning, Company B, 1st Batalion, 28th Marines had reached the western beaches and successfully separated Suribachi from the rest of the island. Without tank or artillery support, it was a battle of individual Marines armed with just rifles, grenades, flamethrowers, and satchel charges. Pillboxes that were eliminated suddenly came alive again and shot at advancing leathernecks from the rear. Kuribayashi’s underground defenses were working perfectly and inflicting numerous casualties on the Marines.

Lieutenant Frank Wright, a platoon commander with Company B, had started the day with 60 men. Only two remained. Captain Dwayne Mears fell with a serious throat wound but he urged his men forward. Corporal William Faulkner of Company C was one of the lucky ones when he was flung backward into a bomb crater after a shell exploded in front of him. A piece of shrapnel dented his helmet, but he escaped injury.

Conditions on the beach were worsening. The Japanese were concentrating a great portion of their ordnance at the trucks, jeeps, LVTs, tractors, and amphibious tractors. The lifeless bodies of Marines and sailors floated aimlessly in the surf, adding to the congestion.

Howitzers and tanks were attempting to get ashore. A mass effort was being made to clear paths for the equipment to move inland and support the assault companies. The 31st Seabees, attached to the 5th Marine Division, managed to get the first bulldozer ashore at noon. Its operator, Seaman 1st Class Ben Massey, was quickly shot in the neck. Machinist Mate Hollis Cash jumped into the seat and began operating the machine. Cranes and caterpillars were utilized to dislodge vehicles mired in the wet volcanic ash. Navy beachmasters were shouting orders into their bullhorns as enemy shells continued to explode among them.

Machinist Mate 1st Class Alpenix Bernar’s LSM ran aground on the wet sand. As the ramp dropped, he prepared to get his caterpillar off as fast as possible. He was the first one to leave the craft, followed closely by the tanks and bulldozers. As he lurched forward, he noticed the bodies of the dead in front of the boat. Not bearing to look, he clenched his teeth and drove over them. He kept telling himself he had to get ashore and level the terraces so the tanks could push ahead.

Meanwhile, the 4th Marine Division sector was even worse. The 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines were in the worst position. They were near the ridge that was closest to the beach from the north. “If I knew the name of the man on the extreme right of the right hand squad of the right hand company of 3/25, I’d recommend him for a medal before we go in,” said Maj. Gen. Clifton B. Cates.

The 1st and 3rd battalions, 25th Marines were trying to reach the ridge and cliff area but, as with all movement on Iwo, it was extremely slow. To their south, the 1st and 2nd battalions, 23rd Marines were running into formidable Japanese defenses protecting the first airfield. Sergeant Darrell Cole of the 1st Battalion, 23rd Marines snuck around one pillbox and slipped grenades through the apertures. He crawled back to his lines and acquired more grenades, returning to the concrete structure to do it again when an enemy grenade landed nearby, killing him instantly. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

The bloodshed on D-day was appalling. Kuribayashi had done exactly what he had planned: let the Marines land, and move inland about 500 yards and unleashed his artillery. Due to the large caliber of the guns, most bodies were horribly mangled. Heads, arms, legs, and other human remains were scattered over a large area. Enemy shrapnel disemboweled one Marine; his entrails, pinkish in color, looked like a giant earthworm in the ash. One company, while in reserve, suffered 30 casualties. There was no safe haven. One individual was lying prone on the beach when a shell furrowed beneath him. The resulting explosion heaved him 50 feet in the air. He landed with a thud and his crumpled body lay motionless on the beach.

Somewhere on Red Beach 1, lying face down in the sand, was the body of Gunnery Sergeant John “Manila John” Basilone of the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines. Basilone was awarded the Medal of Honor on Guadalcanal and was pulled from action to go on War Bond drives. The soft duty did not appeal to the New Jersey native, and he petitioned to be returned to a line company. He got his wish and was killed in action on Iwo Jima the first day. He was posthumously awarded a Navy Cross.

Medical personnel were taxed to their limit. Corpsmen and doctors alike were not spared the enemy’s guns. In one area, two doctors and 16 corpsmen were killed. Another medical detachment landed with a complement of 26 men and at day’s end had lost 11.

The first night on Iwo Jima was described by Time-Life correspondent Robert Sherrod as a “nightmare in hell.” The illumination shells fired from the destroyers created a surrealistic effect on the battlefield. To one Marine, Iwo looked like “another planet.”

Major General Clifton Cates wished he had another six hours of daylight, or even four. “Hell,” he thought to himself, “I’d compromise for two.” He was worried about the 14th Marines, his artillery regiment that had not landed yet. Luckily, the 75mm and 105mm cannon managed to get ashore by dusk. The 13th Marines, the artillery arm of the 5th Division, had also landed some of their pieces. Both units would be sorely needed in the morning when the attack resumed.

Steaming toward Iwo Jima were the 9th and 21st regiments of the 3rd Division. The 3rd Regiment would soon follow. Nearly 30,000 troops were now ashore. An incredible 50,000 men were crammed on an island a mere eight square miles in size.

The Banzai charge “Howlin’ Mad” Smith hoped for did not come. Kuribayashi was too wise for that. He sent out “wolf packs,” two- and three-man squads to harass the weary Marines throughout the night. An enemy thrust containing nearly 40 soldiers was destroyed by elements of the 1st Battalion, 28th Marines as it tried to reach Kitano Point.

Later that evening, Yellow and Blue beaches were closed because the enemy artillery fire increased in intensity. The steady, raucous shriek of the 675-pound spigot mortar shells could be heard as they traveled overhead. Most Marines eyed the strange weapon with curiosity, as the shell left a trail of red flame behind it. Fortunately, it was not very accurate but the remainder of the Japanese arsenal was devastating.

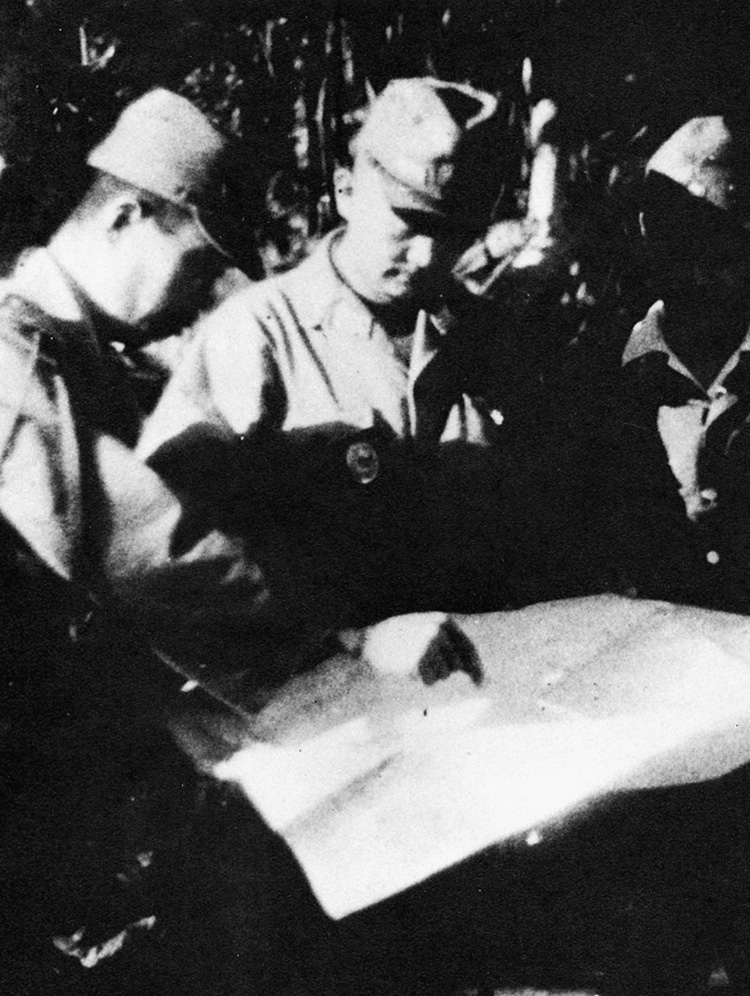

Colonel Harry “The Horse” Liversedge, 28th Marines commander, sat hunched over his maps, preparing the following day’s assault. As he scanned the charts, he realized it was not going to be easy for his troops to seize Suribachi, but it was essential that it be taken, and quickly, to assist those units advancing northward. Ironically, the man from Volcano, Calif., was going after a volcano in the morning.

Dawn on February 20, 1945, was cool, cloudy, and miserable. All units were poised for the attack. The 26th and 27th Marines were ready to move up the west coast. On their right flank were the 23rd, 24th, and 25th regiments, advancing up the east coast.

To the south, surrounding Suribachi, was the 28th Marines. They had to penetrate 1,300 yards of pillboxes, tunnels, bunkers, blockhouses, antitank ditches, machine-gun emplacements, and mortar pits.

Just prior to jumping off, carrier planes strafed and bombed Suribachi’s base. Rounds from the 13th Marines and additional firepower from the mine layer Thomas E. Fraser were added.

At 8:30 am, Lt. Col. Chandler Johnson’s 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines started moving toward Suribachi. To their right was Lt. Col. Charles Shepard’s 3rd Battalion, 28th Marines. The base of the mountain was encircled with broken, jagged rocks and sparse areas of underbrush. Skirting the foundation was a green edging that contained the majority of the enemy’s weapons. The sharp crack of the 5-inch shells from the destroyers could be heard. They drilled over 1,500 rounds into the mountainside and as close as 200 yards to the Marine lines.

Demolitions and flamethrowers became the vanguard for the assault as the 2nd Battalion alone blasted shut over 40 caves. By late morning, the 3rd Battalion, 13th Marines moved their 37mm half tracks and 75mm howitzers closer to the infantry for more accuracy.

Johnson fired off a message to division headquarters saying, “Enemy defenses much greater than expected. There was a pillbox every ten feet. Support given was fine but did not destroy many pillboxes or caves. Groups had to take them step by step suffering severe casualties.”

As the 5th Division was slugging its way closer to Suribachi, the 4th Division was having a hard time as well. Many of the officers became casualties. The 2nd Battalion, 25th Marines lost its commander, Lt. Col. Lewis C. Hudson, Jr, its executive officer, Major William P. Kaempfer, and its operations officer, Major Donald K. Ellis, when a mortar round made a direct hit on their command post (CP). A half-dozen corpsmen from the 1st Battalion, 25th Marines were killed outright as well by an artillery shell. The round also severely wounded seven others. Enemy rounds spared no one. Despite the fierce shelling, the 23rd Marines took the airfield by early afternoon, assisted by 4th Division tanks.

The 28th Marines, however, had moved just 200 yards against Suribachi. The going was treacherous, time consuming, and very discouraging. Kuribayashi transmitted a message to his men defending the mountain. “First, one must defend Iwo Jima to the bitter end. Second, one must blast enemy weapons and men. Third, one must kill every single enemy soldier with rifle and sword attacks. Fourth, one must discharge each bullet to its mark. Fifth, one must, even if he be the last man, continue to harass the enemy by guerilla tactics.”

This was last message sent to Suribachi. Marines from the 5th Engineer Battalion uncovered a cable an inch and a half thick and quickly severed it. The enemy inside the mountain fortress was truly isolated.

At day’s end, the leathernecks controlled roughly one-fourth of the island. The 5th Division had lost another 1,000 men, and the 4th suffered 2,000 dead and wounded. Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal was aboard the flagship Eldorado to observe the battle. The horrendous suffering left him speechless.

LST 779 wedged its way through the wrecked remains on Red Beach 1 and delivered the first of the V Amphibious Corps’ 155mm howitzers. By late in the afternoon, four of the big guns were ashore and ready to pound Suribachi.

During the night the star shells filled the inky blackness. The tiny island trembled from the force of the artillery blasts. Near the eastern side of the mountain, a number of enemy soldiers were congregating in what appeared to be a banzai charge. The destroyer Henry A. Wiley silently slipped to within 200 yards and saturated the area with her 5-inch rounds. It was a long night on Iwo.

February 21 was a cloudy day on Iwo Jima. The thunderous roar from the howitzers of the 13th Marines and shells from the naval vessels offshore hammered the mountain. The bombardment was precariously close to the assault troops as they were pelted with flying rocks, earth, and other debris. Liversedge wanted it to be close. “Ask for all of it Pete,” he told his operations officer, Major Oscar Peatross, “and tell those planes to drop it close—we can’t use air tomorrow.”

As the aircraft peeled off, a ghostly silence fell upon the lines. For a brief moment nothing happened, then one, two, three men, followed by clusters of Marines, stood up and began walking toward their objective. All along the 700-yard line the Marines began to zigzag to avoid the increasing enemy fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Jackson Butterfield’s 1st Battalion, 28th Marines moved along the western beaches while Lt. Col. Charles E. Shepard’s 3rd Battalion hurled itself at the center of the volcano’s fortifications. On the eastern side, Johnson’s 2nd Battalion met stubborn resistance.

Casualties began to multiply. The cry of “Corpsman” could be heard above the din of battle. Corporal Richard Wheeler of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines had his jaw broken by a piece of shrapnel. The same mortar round also wounded another Marine in the same shell hole. While Pharmacist Mate 3rd Class Clifford Langley tended to their wounds, another mortar round burst in the hole. This time, Wheeler sustained a severe leg laceration as the metal fragments sliced his calf muscle. The other Marine was now lying on his stomach devoid of skin and bleeding heavily. Langley ignored his own wounds and kept working on them. As he was doing this, another mortar landed among them. Wheeler and Langley watched helplessly as the projectile burrowed itself in the loose ash. To their relief, it did not detonate.

The fighting around Suribachi was intense. Marines carrying the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) would perform a “leap frog action.” One would fire moving forward while the other reloaded as they inched their way closer to the mountain.

Private First Class Daniel Friday of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines ran to the front of one tank to guide it after the phone was shot from another Marine’s hand. The Arapaho Indian from Wyoming stood in the open and steered the Sherman using hand and arm signals. As a result, the tank’s 75mm gun delivered accurate fire and destroyed several pillboxes.

By day’s end, the 28th Marines had reached the foot of Suribachi. The riflemen had blasted shut hundreds of caves and neutralized numerous pillboxes and other structures.

To the north, the fighting was equally gruesome. The 4th Division was running into Kuribayshi’s main line of defense. By nightfall, the 21st Marines of the 3rd Division were given the word to come ashore. They assembled near Airfield No. 1 to attack in the morning.

During the night, Condition Red was sounded as kamikazes from Japan struck the USS Saratoga. The aircraft carrier managed to stay afloat in spite of being struck by six planes. Not so lucky was the escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea. One kamikaze hit triggered an explosion that destroyed the fire mains and rendered the plane elevator useless. Airplanes, gassed on the flight deck, were soon engulfed in flames. Ammunition began to cook off, and the order was finally given to abandon ship. Over 200 men lost their lives.

February 22 was a wretched day on Iwo. The rain turned heavier, transforming the ash into a slurry mixture. The thick mess wreaked havoc with weapons. The fighting resumed and the all too familiar sounds of the wounded, the roar of artillery fire, and the whoosh of the flamethrowers permeated the air.

As the infantrymen pressed forward, grenades flew at them from cave openings and many fought the enemy at close quarters. No artillery or air support could be given to them because they were too near the mountain.

Major General Keller Rockey came ashore and established his division headquarters in a shell hole near Airfield No. 1. As he and his staff pored over charts and maps, the dull drone of the bulldozers could be heard preparing the 5th Division cemetery. Men from Graves Registration, clad in rubber aprons and wearing gloves that reached to their armpits, were assigned the ghoulish task of gathering the dead. In some cases, only an arm or head was found. Bodies were piled while their final resting places were being dug. Nearby were the thousands of white crosses that would adorn the graves.

With Suribachi finally surrounded, all that remained was to climb to the top and secure it. The constant bombardment, however, had obliterated all paths to the summit. With nightfall, Liversedge halted all combat operations until morning, when the Marines would begin their final assault on the volcano.

Inside the mountain, about 300 Japanese were all that was left of the fighting force. Half the group tried to rejoin other units in the north, while the remainder decided to remain and die fighting in the dark abyss of Suribachi.

There was a slight overcast on Friday, February 23, D+4. The rain had stopped, and the sunlight appeared through the clouds. Suribachi was strangely silent. The fortifications that ringed the volcano were now abandoned, with the Japanese soldiers retreating to the top to make their final stand. The mountain bore the effects of the tremendous shelling. Its scarred slopes revealed the twisted wreckage of the huge naval guns emplaced there. The tunnels, most of which were now empty, were smoldering.

A meeting was held to discuss the course of action. “Colonel Liversedge and I went to the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines CP and talked with its commander, Lt. Col. Chaney Johnson, his executive officer Major Tom Pearce, and his operations officer, Captain Martin Reinemann,” recalled 28th Marines operations officer Major Oscar Peatross. “We emphasized the need to let the rest of the troops know that the mountain had been secured. Consequently, we talked smoke pots and other things and finally decided on Colonel Johnson’s idea of taking a flag up and raising it on the spot where it could be seen over the entire island.”

The most logical route up the mountain was on the northeast side, so Johnson selected Company E. He informed Captain Dave Severance, the company commander, who chose the 3rd platoon to be led by his executive officer, 1st Lt. Harold Schrier.

Just after 8 am, Schrier’s 40-man patrol started its climb to the top of Suribachi. Schrier ordered riflemen on each side of the column to protect their flanks. The extra gear the Marines were carrying slowed them down, and they would stop for a brief rest on their way to the crest. Certain areas had to be ascended on hands and knees. “Those guys ought to be getting flight pay,” remarked one observer.

Schrier’s patrol reached the summit at 10 am The climb had proved uneventful. Everyone peered apprehensively about, but no enemy soldiers were seen. Schrier gestured for the patrol to take up positions on the outer rim. One Marine, in a show of defiance, urinated. Still nothing happened.

As half the patrol was covering the edge of the mountain, the remainder moved toward the center. A firefight ensued when a Japanese soldier was spotted at one of the cave openings. As this was happening, six Marines tied the U.S. flag that Johnson had handed them prior to their ascent to a drainage pipe. At 10:20 am, it was hoisted. This was the first Japanese territory seized by American troops in World War II. Staff Sergeant Louis Lowery from Leatherneck Magazine snapped a picture but this photo would be forgotten when Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal took the now famous picture hours later.

To the Marines on Iwo Jima, however, pictures meant nothing. All they knew was Suribachi had been captured and they did not have to worry about their rear while they moved northward. When the news spread, the island erupted into a tumultuous roar of bells, whistles, and foghorns.

A wounded Marine, lying on the deck of a hospital ship, tried in vain to lift himself up to get a better look at the flag. He was too weak to shout. He slumped back down on his cot and wept.

To the north, the battle was in a stalemate. Gains were minimal as a thousand Marines were falling, dead and wounded, every day. The bitterest fighting was taking place around Airfield No. 2. Shells from the battleship USS Idaho and the cruiser USS Pensacola hammered the center of the island. Cates complained about the ordnance not doing its job, and he requested the U.S. Army’s heavy bombers stationed in the Marianas to provide support.

At 9:30 am, on February 24, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 21st Marines jumped off to seize the airstrip. The enemy had over 800 pillboxes surrounding the field. Companies I and K started running across the runway, led by 1st Lt. Raoul Archambault. Marines made it to the ridge and began a seesaw action to hold the position.

“In the wild fighting they fell on [Col. Masuo] Ikeda’s men with rocks, rifle butts, bayonets, knives, pistols, and shovels,” wrote Richard F. Newcomb in his book Iwo Jima. “In ninety minutes it was over. Archambault and his men were on top of the ridge, the advance had covered 800 yards, and the line was breached. Through the gap poured tanks, bazooka men, mortarmen, and machine gunners, cleaning up as they advanced.”

On the east coast, the 24th and 25th Marines moved closer to the airfield by occupying Charlie Dog Ridge. By the end of day six, the 9th Marines were tapped to land. Over 1,600 were now dead and 4,500 were wounded, but only one-third of the island was in Marine hands. Only the 3rd Marines were left in reserve.

The end of February saw the 26th and 27th Marines involved in bloody fighting on the west coast. They faced one ridge after another as they endured a viscous crossfire. The 9th and 21st Marines were facing Hills Peter and Oboe, while the 23rd, 24th, and 25th Marines were ready to strike at Hill 382, the second highest elevation on Iwo. Hill 382 was a maze of pillboxes and bunkers. Its crest had been dug out and fitted with artillery and gun pits.

To the right of this stood the Turkey Knob, a small rise stripped of foliage. In addition to the usual fortifications, a huge blockhouse, which also doubled as an observation post and communications center, was located there. Eighty-five rounds from a 75mm howitzer failed to put a dent in it. Next was Minami. Originally a small village, it was now a nest of bunkers. Completing this ring was the Amphitheater, an open bowl-shaped depression 300 yards long and 200 wide.

From the tops of these positions, the enemy threw grenades and satchel charges down on the attacking Marines. Armored bulldozers tried desperately to clear away rocks and debris so tanks could get through and assist the infantry. Advances were measured only in feet in some places. The area was soon dubbed the Meat Grinder.

All nine battalions of the 4th Division hurled themselves at the Meat Grinder. By nightfall on February 27, they had the area encircled. The cost, however, was staggering: nearly 800 casualties. Erskine wanted to bring his 3rd Marines into the fight but “Howlin’ Mad” Smith disagreed. The island, he thought, was too congested. It was—with the exception of the front lines.

On March 1, the 28th Marines, which had been in reserve after securing Suribachi, swung into action against Hill 362A on the west coast. Marines from the 1st and 2nd battalions reached the top but were confronted with an 80-foot cliff on the other side.

Also lying ahead was Nishi Ridge, an open area the Japanese had covered from all sides. All the approaches were studded with caves, spider holes, and small niches that held riflemen and automatic weapons. Company C, 5th Tank Battalion supported the advance. Flamethrower tanks were helpful, but the terrain was so impassable only 350 yards were gained.

The attack resumed on March 2 on all fronts. The 3rd Division assaulted Hill 362B in the center of the island. In one area, dubbed “Cushman’s Pocket” after Lt. Col. Robert Cushman, commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, the leathernecks had a tough time. They finally secured it but spent the next two weeks mopping up.

Hill 382 was taken as well by the 2nd Battalion, 24th Marines. Artillery and airpower had pulverized the Amphitheater and the Turkey Knob. Over a ton of demolitions were used as combat engineers closed tunnels and caves. The Meat Grinder, however, had taken its toll—over 3,000 casualties from the 4th Division alone.

With the 26th Marines on the right and the 28th Marines on the left, the 5th Division operated on the western side of the island. The 21st and 2nd battalions, 28th Marines went around the flanks of Hill 362A to assault Nishi Ridge. Four separate tunnel systems were uncovered, one reaching over 1,000 feet in length and having seven different entrances. Tanks had great difficulty maneuvering around a stretch of anti tank ditches in a draw but managed to blast their way through to reach the rifle companies. The Marines found themselves in the midst of natural rock formations where they found fewer concrete structures. Here the enemy relied on nature to provide their cover.

“It was just a maze of tunnels and caves,” wrote 1st Sgt. John Daskalakis of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines. “It was very easy to lose sight of each other. The soil at the northern end of the island was clay-like—grayish in color—almost like a marl type. The Japanese were underneath you and behind you. Men were shot in the back. They had CPs, hospitals and ammo dumps underground. You couldn’t see them. It reminded me of the Devil’s Den at Gettysburg.”

While the leathernecks were advancing north, a damaged B-29 limped into Iwo Jima. As the aircraft made a bumpy landing, a few mortar rounds thumped behind her as she touched down. Marines and Seabees greeted the crew members with slaps on the back. Soon after the aircraft was repaired, the Superfortress was winging its way back to Guam. Before war’s end, over 2,000 B-29s would make emergency landings on Iwo Jima with over 24,000 crewmen saved as a result. They had the Marines to thank for that.

As the days passed, the leathernecks slugged it out with the remaining Japanese defenders. Only 80 prisoners had been taken so far in the battle. Of these, 45 were Korean laborers. The enemy was not surrendering. Many Marines would stop and gawk at the survivors. It was the first time many of them had actually seen a Japanese soldier.

Marines of the 4th Division repelled the only organized banzai attack on Iwo Jima when 1,000 of the enemy charged their lines. Machine-gun and rifle fire mowed down the human waves, some of whom were only armed with spears. When it was over 784 bodies were counted. The Marines lost 90 killed and almost 300 wounded. But the attack signaled the end of organized resistance on the east coast of the island.

Kitano Point was the last stronghold of the Japanese. Just before the attack against it, 75mm and 105mm howitzers of the 13th Marines and the 155mm cannon of the corps artillery let loose over 22,000 rounds. Eight-inch shells from the cruisers also aided in the softening up of the western side of Iwo. The attack moved ahead until the infantry was halted near the high ground that ran southeast from Kitano Point. The 28th Marines were looking over a deep gorge. It was the worst terrain on the island. They called it Death Valley.

Heavy weapons were useless in such narrow and hilly ground so the 75mm and 37mm guns were utilized. The 28th Marines edged their way up the gradual slope, a key position that commanded all approaches to the north. They were ordered to hold on while the 27th Marines swung around from the west. The 26th Marines would also join in and converge on the final enemy stronghold.

By now the Marine divisions were decimated. Companies were now platoon size, and, in some cases, led by corporals. Nerves were strained. Casualties kept coming into the field hospitals with “wounds that make you sick to look at.” Artillerymen, cooks, and clerks were now being sent to the front lines to reinforce the exhausted men.

Of the 21,000 Japanese at the start of the battle, a mere 1,500 remained. Kuribayashi sent his last dispatch to Tokyo, which read in part “The situation is now on the brink of the last … I shall lead the final offensive, praying that our empire will eventually emerge victorious. Bullets are gone and water exhausted … we are ready for the final act.” That evening he ordered the colors of the 145th Infantry burned.

On Wednesday, March 14, 1945, the official flag-raising ceremony was conducted in the southern part of Iwo Jima. As Colonel Davis H. Stafford read the proclamation, the dull sound of gunfire could be heard in the distance. A team of stretcher bearers carried a wounded Marine to a field hospital, and nearby a 105mm cannon roared. The battle was still very much in evidence.

A hushed silence fell over the crowd as “Colors” was played. The flag was hoisted atop an 80-foot pole as the one on Suribachi was lowered. When it was completed, very little was said among the group. Misty eyed, “Howlin Mad” Smith said “This was the toughest yet.”

Two days later the island was declared officially secured. The Marines fighting in Death Valley were stunned. They would spend another 10 days there fighting a stubborn foe.

In the early morning hours of March 26, the Japanese on Iwo Jima staged their last assault. Hundreds of them formed near Airfield No. 3 and quietly crept along a trail heading south. Reaching the tent area that housed the 5th Pioneer Battalion and Army Air Force personnel, they attacked. Caught completely by surprise, these units were overrun in a few minutes. Airmen had their throats cut while they slept.

First Lieutenant Harry Martin of the 5th Pioneers organized a counterattack, rescued two men, and was twice wounded before being killed. He was posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor. It was the last one given in the campaign. In all, 27 Medals of Honor were presented—the most for any single battle in Marine Corps history.

By morning it was over. Over 250 enemy bodies were accounted for and another 18 were taken prisoner. The Pioneers lost nine killed and 31 wounded. Forty-four airmen were butchered and 88 wounded. Rumors were rampant that Kuribayashi led the raid himself, but his body was never recovered.

Soon, the U.S. Army’s 147th Infantry assumed garrison duty on Iwo Jima. Japanese stragglers were captured long after the battle was over. Some survived on discarded food and by drinking their own urine. Only 1,083 enemy soldiers survived. The Marine losses were staggering: 6,821 killed and 19,217 wounded plus 2,648 cases of combat fatigue.

The words of Chaplain Roland B. Gittleson are a fitting memorial to those who paid the supreme sacrifice: “Thus do we memorialize those who, having ceased living with us, now live within us. Thus do we consecrate ourselves the living to carry on the struggle they began. Too much blood has gone into this soil for us to let it lie barren. Too much pain and heartache have fertilized the earth on which we stand. We here solemnly swear; this shall not be in vain! Out of this, and from the suffering and sorrow of those who mourn this, will come—we promise—the birth of a new freedom for the sons of men everywhere.”

Author Al Hemingway is a U.S. Marine Corps veteran of the Vietnam War. He is an expert on the island fighting during World War II in the Pacific and resides in Waterbury, Connecticut.