By Robert A. Lynn

The 1944 invasion of France, the breakout from the beaches, the surprise German counterattack in the Ardennes, and the final reckoning with the Third Reich have all been exhaustively chronicled. Whole libraries have been written on these events, all of which were victories. Even the Battle of the Bulge became a victory in the end. But of the U.S. Army’s greatest defeat in Europe, an engagement most modern observers agree should never have happened—a terrible battle of attrition in a remote German frontier forest—there is virtually nothing. That’s because it was a defeat and, for obvious reasons, the top brass doesn’t like defeats and discourages attempts at writing about them.

At the time, the few journalists who ventured into the Hürtgen Forest (Ernest Hemingway being one of them) called the slaughter taking place there “Passchendaele with tree bursts” (referring to the 1917 battle now synonymous in British Army annals with useless human carnage). But the GIs who went into that forest to fight and to die by the thousands had another name for it: “the Death Factory.” That grim sobriquet was never publicized by the media back home during that gray, bitter winter more than 80 years ago, for obvious reasons.

By August 1944, Allied forces had broken out of the hedgerows of Normandy; Paris had been liberated; and the German Army was fleeing, apparently in disarray, back to the Reich. Many Allied soldiers believed that, with just a little push, the war with Germany would be over by Christmas. At Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF), however, there was less optimism because they saw the German resistance stiffening at the Siegfried Line, Adolf Hitler’s defensive line on the western border of Germany.

The Siegfried Line, or West Wall, was a series of prepared positions that would be very costly to assault. General Dwight D. Eisenhower hoped to accomplish his mission of defeating Germany with a minimum of casualties, but looming ahead of the rapidly advancing Allies was this forbidding network of defenses. Part of that defensive system was the dark and brooding Hürtgenwald—the Hürtgen Forest.

Trying to avoid a direct assault on the Siegfried Line and the Hürtgen Forest, Eisenhower weighed the situation. First, it was painfully apparent by September 1944 that supplies were becoming short and his two dynamic and demanding subordinates, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton and Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery, were in direct competition for supplies and the ear of their commander. As it turned out, Montgomery was able to convince Eisenhower to attempt a combination land and airborne assault toward Arnhem, called Operation Market-Garden, that would outflank the Siegfried Line to the north. One of the reasons Eisenhower allowed Montgomery to make his attempt to defeat the Germans in Holland was the specter of the Hürtgenwald and the Siegfried Line. But toward the end of September it was obvious that Montgomery’s “dagger thrust” into Holland was a failure and new plans had to be considered at SHAEF.

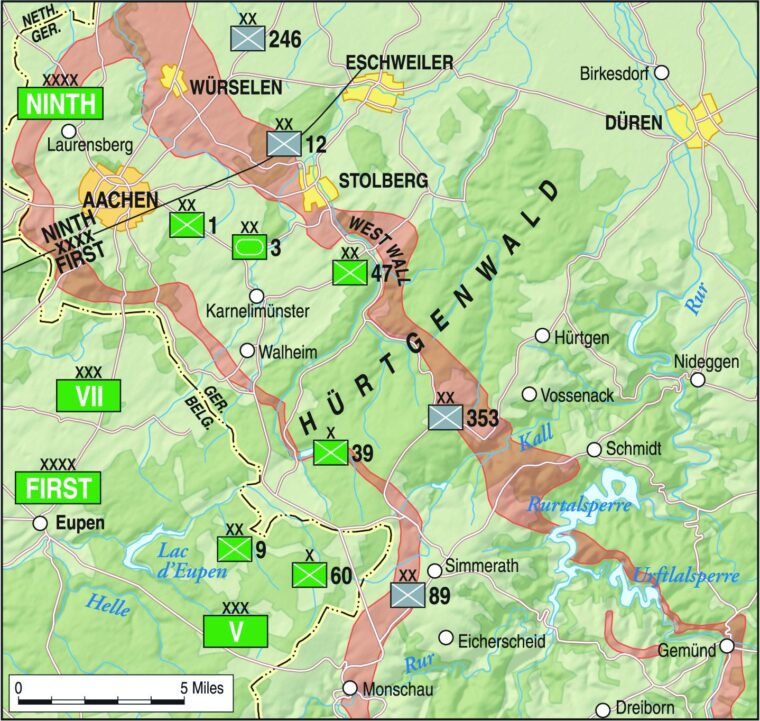

Meanwhile, by the beginning of September 1944, Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges’ First Army had breached the Siegfried Line in two places, the most significant of which was at the city of Aachen. Hodges’s 750,000-man army comprised three U.S. Corps, the VII, V and VIII, deployed from north to south facing the Hürtgenwald.

Feeling that the Germans were nearly defeated, Maj. Gen. “Lightning” Joe Collins, commander of the 80,000-man VII Corps, proposed to his superior, Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, a “reconnaissance in force” to breach the Siegfried Line before the Germans had time to put troops into the fortifications. Neither man considered the realities of the Hürtgen Forest.

The region started some five miles south of Aachen, where it was a collection of several woods extending 50 square miles within a triangle formed by the cities of Aachen, Duren and Monschau. From the southwest to the northeast two ridges point toward the Roer River. On the northern ridge lie the small townships of Hürtgen, Kleinhau and Grosshau, with the ridge itself extending some two miles. The southern ridge stretches from Lammersdorf to Schmidt, townships which were then mainly unknown outside the area, even to the Germans themselves. Between these two ridges is the deep gorge of the little, but fast-flowing, River Kall.

The terrain, tough enough already, had steep, wooded heights reaching up to 1,000 feet and packed with close-knit fir trees and fast-flowing little streams racing through the tight valleys.

For the attacker, the Hürtgen Forest was made even more difficult by the German fortifications: concrete pillboxes and bunkers fronted by “dragon’s teeth,” with interlocking fields of fire, concrete stumps to stop the advance of tracked vehicles, and extensive minefields filled with the dreaded “Schu” mine, which couldn’t be detected by mine detectors, and “Bouncing Bettys,” known more irreverently by the GIs as “de-ballockers.” These crude but effective devices, with a series of metal balls that exploded to about waist height, had devastating results when detonated. They were also called “50-50 mines” because of the chances once you stepped on it. If you hit it with your right foot, the rod flew up your right side, but if you hit it with your left, you’d end up singing tenor.

To guard the right flank of this “reconnaissance in force,” Collins proposed to send an American force into the forest to root out the second-rate German 353rd (and later the 275th) Infantry Divisions. But unknown to Collins, the attack through the forest would cost him the mobility and superiority given him—at that time—by his tanks and aircraft. Instead, the advantage would shift to the defenders.

To Hodges’ infantrymen, contained in eight veteran, hard-fighting combat divisions, the Hürtgenwald promised to be a dismal fight. Infantry without proper support from artillery, armor and air would have a difficult time in any terrain. The Hürtgenwald’s road network was very poor, and the fall rains turned what few trails there were into knee-deep quagmires. Not only would the advance be slow, but the resupply of ammunition, food and equipment would be almost impossible. To make matters worse, the combat infantry veterans knew that to be wounded in such terrain meant long hours of travel to aid stations, mainly by walking or being carried on a hand litter—if that was even possible in such circumstances. Moreover, artillery was fired so that the shells would burst in the treetops, and deadly splinters of wood and steel would rain down on the lightly protected foot soldiers, Germans and Americans alike. It was poor terrain on which to fight an infantry battle.

Mesmerized by the rapidity of the advance across France, Hodges allowed his corps commanders to start their move against the German positions on September 12. The defending German forces in the forest, however, were veteran units. Unknown to Hodges, or to higher headquarters, many of those combat units had their staffs intact and were being quickly bolstered by reinforcements from the Reich.

The Allies made a critical error by underestimating the resilience of the German war machine.

Simply put, the Americans had morale and momentum, but the equation was balanced by the Germans having the element of surprise and a desperation born of now having to defend their homeland. The great German military theoretician, Carl von Clausewitz, argued a century before that in combat a determined defense was actually the strongest method of waging war. While the offense promised more of a decision, a well-prepared defender could even the odds. That was to prove true in Hürtgenwald in the fall of 1944.

Complicating matters for Allied planners was the Roer River on the eastern side of the forest. It was not so much the river itself that presented a problem—it was the number of sizable dams which, if destroyed, could flood the area. Thus if Hodges’ troops crossed the Roer and the Germans opened the dams and flooded the plains, the attackers could very well be trapped. Initially the dams were not an Allied objective, nor was the small town of Schmidt, which controlled the routes to the dams. That neither Hodges nor his corps commanders seemed to see the value in taking the town or the dams proved a costly oversight.

The men of the U.S. 9th Infantry Division led the assault and, at first, their progress was good. The GIs quickly penetrated the outer defenses of the Siegfried Line, advanced 6 miles and captured 400 prisoners while sustaining just a handful of casualties. But on September 15, the 60th Regiment of the 9th ran into roadblocks, pillboxes, narrow trails, thick minefields and bitter German counterattacks. German real estate became expensive, with gains measured not in miles, but in yards.

Now the “PBI,” or poor bloody infantry, and combat engineers took over to clear the pillboxes that stopped the American advance. The combat engineers crawled forward through the mud to prod with their bayonets for the enemy mines, made even more dangerous because they were often booby-trapped. By the time both the 9th Infantry Division and the 15th Combat Engineer Battalion were moved temporarily to the rear at the end of September 1944, they had lifted l,352 mines, defused 100 booby traps, and neutralized 125 fortified pillboxes while under fire. But the 9th’s casualties were horrendous, worse than they had suffered in North Africa, Sicily and France. Its 60th Infantry Regiment, which bore the brunt of the fighting, suffered in the end almost 100 percent turnover in combat personnel since September 3. To begin with, the forest had beaten the attackers, but they would be back again.

After Montgomery’s operation to end the war quickly by going through Holland into Germany had failed, there was more emphasis on a broad assault all along the German border. The attack kicked off on October 6 in the Hürtgen. The initial objectives were the villages of Germeter and Vossenack, with a southward drive over the high ground beyond the Germeter-Hürtgen Road. The objective was to continue through the Hürtgen Forest and have as its final aim the clearing and seizing of the Schmidt-Steckenborn ridge. The 60th Regiment and, to its right, the 39th Regiment of the 9th would go in to clear the forest on a three-mile front, while the 47th Regiment would secure the left flank and carry out day and night patrolling as well as supplying the reserve in an emergency.

In his riveting and haunting Battle Of Hurtgen Forest, Charles Whiting described that “the firs in the Hürtgen were so thick that they interlocked. The advancing infantry would be faced with a solid mass of dark, impenetrable green. At the level of a crawling man there was room, so that it was as if the individual soldier were entering a dark green forbidden cave that immediately cut him off from his fellows. In these caves regiments lost battalions and battalions lost companies. Even at the company level it would be difficult to maintain control. In the end it came down to squads of men fighting on their own, cut off in a claustrophobic green little world without support of tanks, aircraft, or artillery.”

Into this dreadful maze of mystery and darkness, the 9th began its advance once again after both air and artillery support—such as it was—had been delivered. But German resistance was so heavy that by the end of October 6 it was costing the 9th exactly one man lost for every square yard of ground captured. Aid stations filled up so rapidly that 2,000 men were being air-evacuated daily from the First Army’s front, back to England, and they were only the serious ones.

The fierce German resistance was led by none other than Field Marshal Walter Model, a loner and a ruthless commander much hated and feared by his subordinates but loved by his front-line soldiers, or “front swine” as they proudly called themselves. He quickly assessed the situation and took charge by using anything and anyone who could fire a weapon: reserve units, police battalions, convalescent companies, training units and stomach battalions.

For four long, bloody days, both the 39th and 60th regiments continued to battle the Germans while their casualties mounted steadily. Tanks were brought up to assist in their advance but found they had to bunch up, and thus became easy marks for the German artillery. Combat engineers were lifting mines by the hundreds. In one area, they estimated there was a Teller mine every eight paces for three miles. In one narrow firebreak they found 500 of the deadly devices.

Heads began to roll at 9th Infantry Division headquarters. The assistant divisional commander, the 9th’s 60th Regimental colonel, and the division’s chief of staff were relieved. (The division’s new chief of staff, incidentally, was the commander of the 34th Field Artillery, Col. William C. Westmoreland.) But the 9th kept attacking until October 24 when they were finally relieved by the 28th Infantry (Keystone) Division. The 9th’s casualties had been enormous: For a gain of exactly 3,000 yards on a 3-mile front the division had suffered 3,836 casualties, or 30 percent of its strength.

The 28th and its commander, Norman “Dutch” Cota, were ordered to capture the Hürtgen township of Schmidt, which controlled the road network that would provide additional lateral supply routes for the main drive on the Rhine by Collins’ VII Corps . Cota had orders to accomplish this mission by November 5. Cota protested both to V Corps commander Maj. Gen. L.T. Gerow and Hodges on the dangers of attacking the Germans head on, but to no avail.

As dawn broke on that cold, damp morning of November 2, American aircraft and artillery did the best they could. Then the 109th, 110th and 112th Infantry Regiments advanced. What followed mirrored or surpassed the horror of the Civil War’s Battle of the Wilderness in 1864 or the Argonne Forest fight in 1918. The Germans put up a fierce resistance, exacting a huge cost on the Americans. Consequently the regiments moved at a snail’s pace. Communications broke down. Then discipline cracked. By the end of the day, the 28th’s advance was stalled.

But on the following day, things got better for the 28th. Aided by a combat command of tanks from the 5th Armored Division, men of the 112th Regiment captured Schmidt. But as night fell, a sense of uneasiness came over the Americans. As supporting tanks advanced forward in relief, they found the “road” to Schmidt, called the Kall Trail, too narrow and unstable under the weight of armor. The combat engineers moved up to work on the trail, and finished by the morning of November 4. But as the tanks were advancing, one rolled over a mine and lost its track.

Only three tanks were able to negotiate the trail to Schmidt before the Germans counterattacked with artillery, tanks and men. The scene was horrendous. The German Mark IV tanks rolled over American mines and kept coming. Nor were GI’s bazookas a match for the Mark IVs. Soon the men of the 3rd Battalion, 112th Infantry, broke in a panic. Both officers and NCOs attempted to rally the troops and eventually were able to bring some order to this chaotic situation.

Cota now had Eisenhower, Hodges, Collins and Gerow breathing down his neck to get the attack rolling again. He immediately sent two badly shaken battalions and seven tanks up the Kall Trail to attack elements of a German infantry division and the famed 116th Panzer Division (The Greyhounds), who had been in the forefront of the fighting since D-Day.

But as the American tanks inched forward, they ran into Germans on the Kall Trail. A fierce and bloody fight ensued with heavy casualties on both sides by the end of the day. Neither side could make progress and both Germans and Americans then fell into an exhausted sleep.

Before disaster could overtake the 28th, the battle-worn survivors of the 112th and 110th regiments, plus engineers and tankers who supported them, began their withdrawal back down to the Kall River. But even this withdrawal had a price.

Next, Cota ordered two mutilated battalions (hastily reinforced by five hundred men) to support the drive of the 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, on what was known as the Monschau Corridor.

This second attack on Schmidt would become the most costly American division-strength attack during all of World War II. The 28th’s casualties were estimated at 6,184, or 45 percent of their original strength. As the official U.S. history of the battle states: “It represented a major repulse to American arms.”

Nevertheless the commanders were so intent on clearing out the forest that they ordered a massive offensive. On the morning of November 16, Operation Queen was launched into the Hürtgen Forest with a force totaling 100,000 men, including First Army’s V Corps (8th, 28th Infantry and 5th Armored) and VII Corps (1st, 4th, 104th Infantry and 3rd Armored), as well as Ninth Army’s XII Corps (84th, 102nd Infantry) and XIX Corps (29th, 30th Infantry and 2nd Armored). Air support would be provided by the U.S. 8th and 9th and the Royal Air Forces as well as artillery.

After a long and thundering barrage, the new offensive set off. But like every other assault in the forest since mid-September, it quickly ground down. The weather was cold and wet, and the German resistance determined. Indeed the Germans had another reason for holding the Americans in place. They could not let the GIs cross the Roer for fear of discovering and upsetting the massive assemblage of German divisions gathering for their last great offensive. Thus for the next four weeks both sides fought one another, pouring in more men and materiel but to no great advantage.

On December 15, the GIs were ordered to dig in and await new orders. They never came because of the surprise attack by the Germans the next day through the Ardennes, south of the Hürtgenwald. Then, not only did the Battle of the Bulge just south of them divert the attention of senior commanders, but also overshadowed the immediate and long-term memory of the horrific fight of attrition in the Hürtgen.

As December 1944 slowly gave way to January, and then February 1945, and the Battle of the Bulge was turning into a defeat for Hitler’s armies, a new and final effort to take the Hürtgen Forest was in the making. This time the 78th Infantry Division of V Corps, with massive artillery support, began its attack on “the Death Factory” on February 5, 1945.

At first, the attack went off well. Combat engineers and a combat team from the 7th Armored Division were quickly dispatched to assist in the offensive and the Americans moved forward, but as the Germans became aware of the imminent threat to the Ruhr dams, their resistance stiffened. Then a mix-up in orders from higher headquarters confused both the 309th and 310th Infantry Regiments. This, and nightfall, halted their advance.

They weren’t the only ones confused. Brig. Gen. James M. Gavin, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, who attacked on February 7 on the flank of the 78th, immediately surveyed the terrain and went to V Corps’ headquarters. He posed one question to both Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner, then in command of V Corps, and Maj. Gen. Edwin Parker in command of the 78th: “Why in the world had we attacked through the Hürtgen Forest in the first place?” Gavin received no reply because that was a “no-no question.”

Meanwhile, to the north of the Hürtgen Forest, 1,000,000 Allied soldiers of both the U.S. Army’s Ninth Army and Montgomery’s First Canadian Army waited for the 78th to capture the dam at Schwammenauel before the Germans blew it up. If the Wehrmacht blew the dams, millions of tons of water would flood the flat plain on both sides of the Roer and the mobility of the Allied armor would be lost.

The Germans turned every cottage and barn into a strongpoint that had to be reduced by a formal, planned attack. Casualties mounted on both sides, but with the support of the 744th Tank Battalion and the 60th Infantry Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division, the Americans were able to seize the dam intact.

After more than five months, engaging eight infantry and two armored divisions, plus several smaller U.S. units, the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest had finally ended. During the struggle most of the rifle companies suffered up to 50 percent casualties in as little as two weeks. In two unfortunate regiments, the 9th Infantry Division’s 60th Regiment and the 4th Infantry Division’s 22nd Regiment, the losses were 100 percent.

By the end of the horror, 30,000 Americans had died or were wounded, and many thousands more cracked and went down with combat exhaustion, no longer able to cope. Company commanders refused to attack, battalions broke and ran away, even a regimental commander seemed to desert his outfit. By the time the battle had reached its high point, the top brass was relieving divisional commanders due to their apparent lack of drive and will to succeed.

The United States lost more than 25 percent of all troops engaged, exceptionally high for American casualties in World War II. Despite the fact that German records were lost in the last days of the war, it is most probable that their casualty rates were even higher.

The Hürtgen Forest campaign also produced a postwar bitterness, especially on the part of the U.S. 28th “Keystone” Division (Pennsylvania National Guard). The veterans felt that their operations, from November 2 to 16, were poorly planned, and represented the undue optimism by Hodges and then V Corps Commander Lt. Gen. Gerow that the Germans were all but beaten, and that combat in this area, which offered so little inroads for support and resupply, would be against half-hearted defenders.

The IX Tactical Air Command (TAC) was tasked to support U.S. operations in the Hürtgen Forest, but as the battle continued into late October and early November, rains and then snow set in, making flying a near impossibility. When they could fly, the terrain was hard to see. Moreover, the constant pounding of artillery from both sides made landmarks difficult to spot from the air. Simply, through no fault of their own, the much-vaunted American air arm did not function well in support of combat operations. Ground commanders had perhaps expected too much from the IX TAC.

By mid-November, combat in the mud, snow, cold and chewed-up terrain began to produce serious challenges for the Americans. Physical problems had always been present in the cold and damp of the forest, but by November, unit commanders began to show severe signs of strain, and many had to be relieved of their commands, from company level up. Individual replacements sent for the bloodied units were very quickly killed or wounded in higher percentages than in other units committed outside the Hürtgenwald. To put this into perspective, the 4th infantry Division went into combat on November 16, and by the last week of the month it had lost 6,000 troops—4,000 in battle and an alarming 2,000 to trench foot, pneumonia and combat fatigue. The Hürtgenwald was literally consuming U.S. combat divisions.

In mid-November, Allied intelligence finally realized that the Germans had pulled themselves together, but they never did fully comprehend the German order of battle. Attacks from the air, mainly carried out by the Royal Air Force against the Roer dams, merited very little. All in all, the Hürtgen Forest operation was a dismal failure.

The surprise German Ardennes offensive, starting on December 16, ended the first and major phase of the Hürtgen Forest operation. For all the reasons cited above, the offensive thrust into the dark woods was a battle which, as Gavin later stated, “should not have been fought.” Based on a poor intelligence picture of the enemy and the terrain, the United States believed in a quick victory of the types experienced in July and August. The error resulted in a campaign that failed, and produced very heavy losses of life and blood.

Heroism was accepted as nothing less than duty in the Hürtgen Forest, but the question still remains: Was the attack on the forest necessary in the first place? It is ironic that of all the Americans killed in the Death Factory, only one is really recalled today: Private Eddie D. Slovik, 3689415, Detroit, Michigan, February 18, 1920–January 31, 1945, the only American shot for desertion in World War II.

I have never quite understood why the allies though it necessary to go through the Hurtgen forest. Going back to Rome’s lost legions and even Grant’s campaign in the Wilderness, it was known that forest campaigns should be avoided wherever possible. Considering the strength of the allies and the rapidly deteriorating condition of the German forces, it would seem an alternate approach to the invasion of Germany should have been more seriously considered.

Venray and Overloon?

Besides Mr. Whiting’s book, Cecil Currey’s “Death of a Division” details how the overconfidence of the U.S. Army’s high command, plus its unforgiveable negligence in reconnaissance of an extremely rugged forested terrain, coupled with its stubborness to admit its errors and halt the slaughter sooner, was the main factor in the horrendous losses suffered by the U.S. infantryman. Currey’s book concentrates on the 28th Infantry Division but gives an overall picture of other units involved. The powers that be kept feeding units into the meat grinder of a well defended area instead of taking a breather and asking themselves is the cost worth this?

To make matters worse, after the 28th suffered hideous losses in the Hurtgen Forest fighting, they sent the division, what was left of it, to a “quiet” area, on the front line, to recover and build its numbers back up with replacements. And where was this quiet area? The Ardennes Forest, the area used by the German “Wacht am Rhein” offensive – the Battle of the Bulge. The high command failed on reconnaissance there also, and again the 28th Division paid the price.

My father served in the 28th division, no wonder he never talked about his war experiences. RIP in peace, Daddy❤️🪖🇺🇸