By David A. Norris

The Herald, like other major New York newspapers, was packed with classified ads on November 1, 1863. In the personal column, Jenny asked Charley to “let me know if you are better yet, and don’t keep me in suspense.” J.W. promised if “the lady with whom I had an engagement … on Thursday, at one o’clock, which I regret my inability to keep” will send him a letter, “she will hear something of interest to her.”

Frank advised Kate or Maggie that “I shall not call for the letter.… I desire neither to see you again nor to hear from you. You know the reason why.” Additionally, a ring of Confederate spies announced that they were going to capture a Union Navy gunboat and spring 2,500 captive Rebel officers from prison at Johnson’s Island, Ohio.

Newspapers of the 1860s were crowded with advertising. Along with the usual commercial and business advertisements was a new category of announcements known as the personals. Rather than the traditional advertisement that tried to draw as much attention as possible, the personal was a message between one individual and a very small clientele, sometimes only one person.

Some personals were, indeed, very personal. Under the cover of initials or pet names, would-be lovers flirted. Amorous couples arranged trysts or sent apologies and explanations for missed meetings. Families sought missing relatives. Other ad buyers discreetly touted services, such as astrology readings, fortune telling, or phrenology, or offered to buy second-hand furniture or clothing.

By the end of the 1850s personal ads had established the practice of sending anonymous coded messages under false names. A correspondent of the Charleston Mercury noted in 1859 that the personals were “well understood, under all their ingenious cryptographic and other preconcerted evasions, to refer to assignations, or dealings in counterfeit money…. The Herald is a safer medium than the postoffice (sic), as nobody can tell who pays for the advertisement—it generally being sent to the paper with the accompanying money. Instead of being the most public vehicle of intelligence, it is, in fact, the most private.” It is little wonder that such ads were a useful way for Civil War spies to smuggle messages to each other.

Personal ads were most effective when placed in newspapers with wide distribution. During the Civil War big city dailies, such as the Herald in New York, circulated across the United States. Indeed, they crossed the Mason-Dixon Line easily and were eagerly read across the Confederate States as well.

It is impossible today to identify the writers and intended recipients of the vast majority of personal ads from the 1860s, but there are a few well-documented examples involving Civil War espionage.

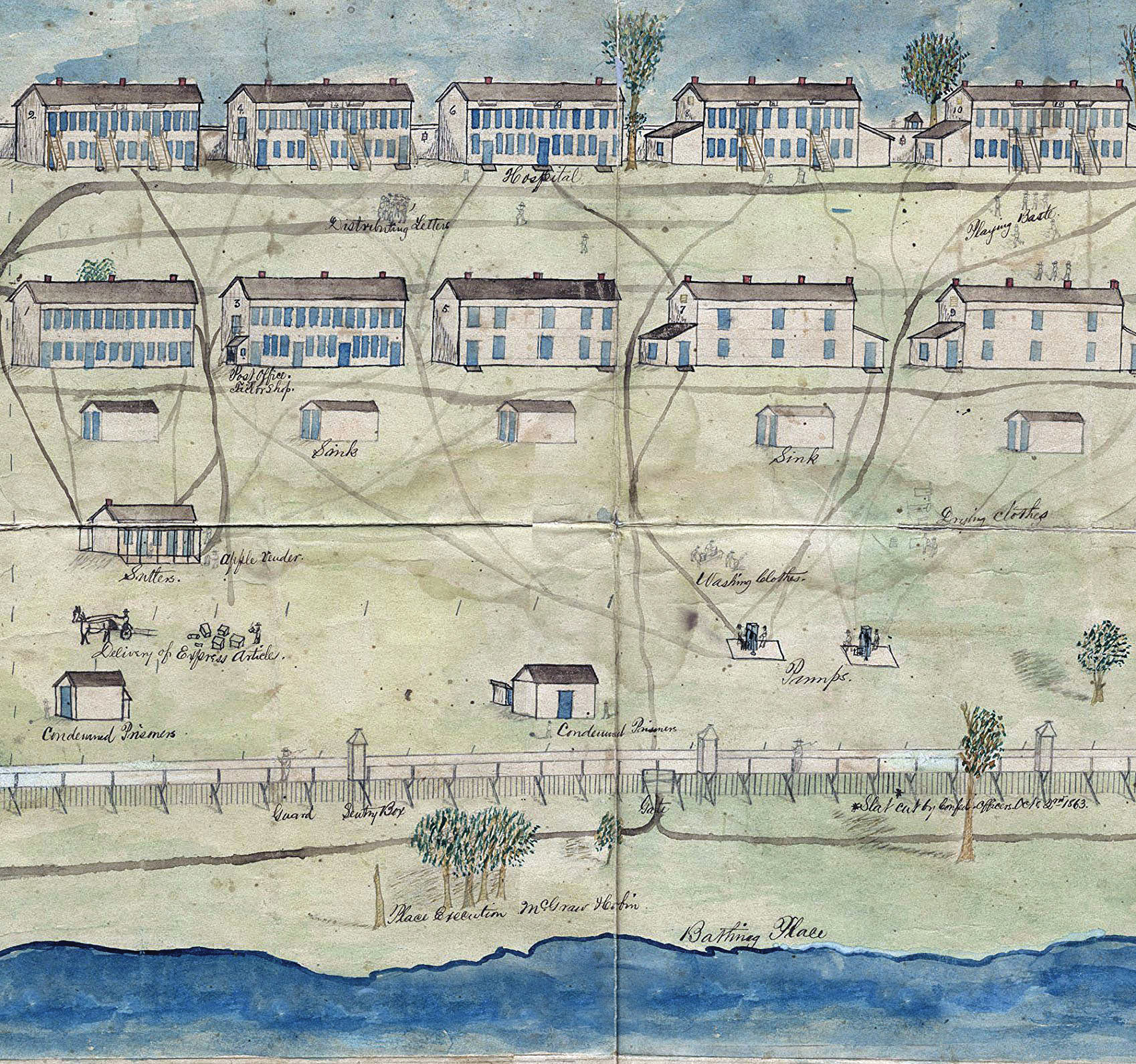

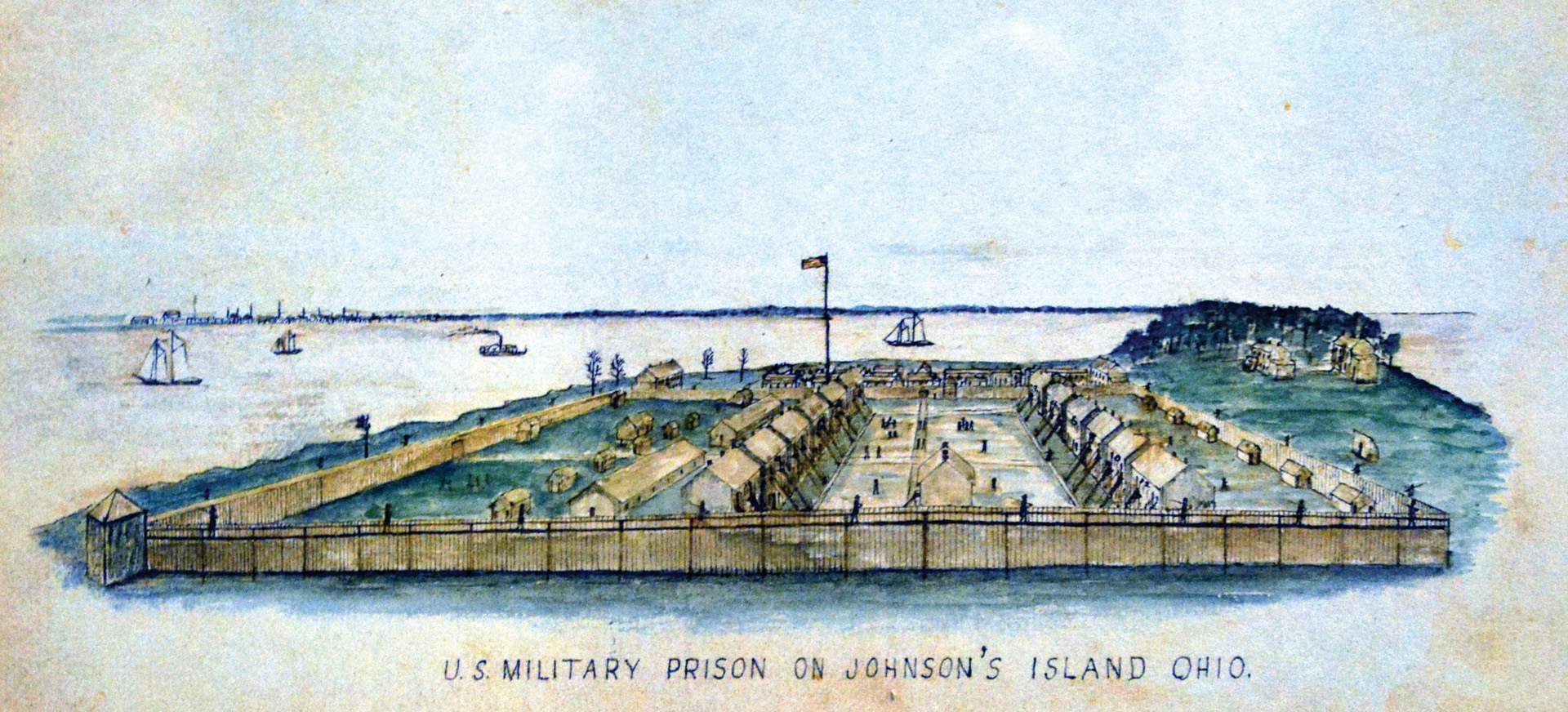

In 1863, the Confederates contemplated a raid to free captives from the Union prison camp at Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie, near Sandusky, Ohio. Canada, then under British rule, offered neutral ground for organizing and launching such an expedition away from the Union authorities. Early plans were shelved because Richmond was reluctant to complicate relations with the United Kingdom by violating Canada’s neutrality.

New Rebel prisoners poured into Johnson’s Island following the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, bringing the total captive population to about 2,500 officers by October 1863. The prospect of getting back so many prisoners of war tempted the Confederate Navy into reviving the plan to raid Johnson’s Island.

Lake Erie was guarded only by the 163-foot-long USS Michigan. The steamer was the U.S. Navy’s first iron-hulled warship when she was launched in 1842. At the time of the Civil War, the Michigan was armed with a 30-pounder Parrott rifle, five 20-pounder Parrotts, six 24-pounders, and two 12-pounder boat howitzers. In Confederate hands, the Michigan’s battery would overwhelm the garrison at Johnson’s Island. With Lake Erie’s only available Union warship in Confederate hands, the raiders could seize as many civilian vessels as needed to ferry the prisoners to Canada.

In charge of the mission was Lieutenant John Wilkinson, a Virginia native who served in the antebellum U.S. Navy. Canada had to be the staging point of the expedition. Wilkinson wrote that “his sole explicit instructions” were “not to violate the neutrality of British territory. How this was to be avoided seemed ever impossible to me.”

Including Wilkinson, 22 men, mostly officers, were assigned to the expedition. Among them was Colonel William B. Ball, transferred from command of the 15th Virginia Cavalry to serve as an acting master in the Navy while on this mission. Only two of his top officers, Lieutenants Benjamin Loyall and Robert D. Minor, were told all the details of the plan. Somehow, the idea spread that the men were bound for England to bring home some Confederate vessels obtained there. Wilkinson was happy to let his men, as well as any newspapermen or other outsiders, believe the rumors.

There was little time to lose, as it was getting late in the year. Wilkinson had to execute his plan before ice prevented him from maneuvering the Michigan to cover Johnson’s Island. On the night of October 7, 1863, the men left Wilmington, North Carolina, aboard the blockade runner Robert E. Lee,which was under Wilkinson’s command for the trip. Wilkinson eluded pursuit and brought the steamer into Halifax, Nova Scotia.

To finance the mission, the Confederate Navy Department provided $35,000 in gold. In addition, the Robert E. Leecarried a shipment of cotton to be sold on behalf of Wilkinson’s operation. In Halifax, the cotton brought another $76,000. Most of the money was earmarked for getting the freed prisoners back to the South.

Traveling by different routes, Wilkinson’s men left Halifax and reassembled on October 21 in Montreal, Quebec. Using assumed names, the men checked into boarding houses, which offered more privacy than the large hotels. The Rebel spies had orders to stay inside much as possible and never leave their rooms for more than half an hour.

To alert the prisoners at Johnson’s Island, Wilkinson relied on exiled Southern sympathizers living in Canada, such as George P. Kane, former head of the Baltimore police, and former Baltimore liquor dealer Patrick Charles Martin. Lieutenant Minor reported that Johnson’s Island prisoners Brig. Gen. James J. Archer and Maj. Gen. Isaac Trimble wrote to Beverly Saunders, a Confederate sympathizer in Baltimore. Saunders passed the letter to Martin’s wife, Mary, and it reached Wilkinson’s circle. In their letter to Saunders, Archer and Trimble asked that Confederate agents communicate with them through coded messages in the personals section of the Herald.Evidently, the communications were to be addressed to “A.J.L.W.”

A personal written for Archer and Trimble appeared in the Herald each day from November 1 to November 6. Minor referred to the ad in an 1864 report to Rear Admiral Franklin Buchanan, and Wilkinson mentioned the advertisement in his 1877 memoir Narrative of a Blockade Runner. In the Herald, the advertisement addressed to A.J.L.W. read, “Cannot comply with your wishes till after Wednesday, the 4th of November. Your solicitude is fully appreciated, and a few nights after that date the carriage will call for you, and the present seeming obstacle will be overcome. Be ready.”

Wilkinson recruited a few more volunteers among Confederate refugees in Canada. Some were exiles; others had escaped from POW camps. One man named Thompson had escaped from Johnson’s Island the previous winter by crossing to Canada across the frozen surface of Lake Erie.

The raiders’ arsenal consisted of 100 Colt revolvers and a plentiful supply of ammunition. Butcher knives stood in for cutlasses. For bigger guns, they obtained two 9-pounders. Buying cannon balls would of course attract unwanted attention, so they purchased some dumbbells as substitute 9-pounder ammunition.

A Private Connelly slipped into Ogdensburg, New York, with money to buy passage for the raiders aboard one of the steamers plying the Welland Canal and Lake Erie. The Confederates would disguise themselves as laborers and pretend that they were on their way to jobs at the Chicago Water Works. Labeled as “machinery” bound for Chicago, crates containing the raiders’ pistols, ammunition, and 9-pounders would be packed in the hold.

Once out of the canal and on Lake Erie, Wilkinson’s men would take over the steamer and mount their two cannons. They planned to arrive off Sandusky about sunrise and, “as if by accident,” collide with the Michigan. After throwing grappling hooks to fasten the two vessels together, the Confederates intended to swarm aboard the warship. Then, they could turn the guns of the Michigan on the prison.

On the verge of setting the plan into action, the operation collapsed. Minor learned that one of their band, a Canadian named McCuaig, “became alarmed at the last moment.” McCuaig revealed the plans to a member of the provincial cabinet, who immediately notified the governor-general.

Washington was alerted very quickly after Viscount Monck, the governor-general of Canada, learned of the plot. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sent a barrage of telegrams late on Tuesday, November 11. In a timely, albeit inaccurate, manner Stanton tipped off Maj. William S. Pierson, commander at Johnson’s Island, of a scheme to attack the prison with four chartered steamers from Canada. The Michigan sowed mines in the channel leading to Johnson’s Island, and three steam tugs were chartered as emergency guard vessels.

Stanton also telegraphed David Tod, the governor of Ohio. Tod ordered troops to reinforce Pierson’s garrison and sent six Parrott guns from Cincinnati. The mayor of Buffalo received a telegram warning that the Confederates intended to attack his city with the freed prisoners.

Minor said that he and Wilkinson along with some of the other spies stayed on for five to 10 days after the news broke. Canadian authorities made no attempt to arrest the Confederate agents, and they eventually returned to Halifax to make their way back to the South. With the onset of winter, the navigation routes were blocked by ice, so they traveled by sleigh through a bleak and frozen landscape.

Another Confederate operation unfolded on Lake Erie the following year. Led by Acting Master John Yates Beall, 20 Rebel naval personnel in civilian clothing seized the steamers Philo Parsons and Island Queen. But, one of Beall’s agents was arrested and revealed what he knew of the plan. Beall abandoned the mission, leaving the Michigan alone to guard Johnson’s Island until the end of the war.

Nothing seems to be known for certain about any further communications to or from the Johnson’s Island prisoners through the personals in the Herald after McCuaig betrayed their escape plan to the Canadian government. However, a few ads that appeared in the following days hint of the possibility that the prisoners at Sandusky received some final messages.

An ad that ran on Sunday, November 8, 1863, read, “J.W., J.W., we are doomed to disappointment. Cannot see you Sunday. Will on Monday, if it rains on Tuesday. M.” And, a November 9 ad read, “A. Not this week. See next Monday’s Herald. Steamer.” Next Monday, November 16, there appeared a cryptic message, “A. – Friday. – Steamer.” However, on Friday, nothing appeared in the personal column from “Steamer.” If these messages did pertain to the intended raid on Johnson’s Island, there was no need for a followup from “Steamer.” All of the plans had fallen apart, and the agents were making their way back to the Confederacy.

Southern newspapers formerly scoffed at the personals. On October 26, 1861, the Charleston Mercury said that “the increasing length of the ‘Personal’ advertisements in the Herald shows what open and unblushing profligacy is going on in Gotham.” Later in the war, though, these advertisements were seen in a more practical light. Letters could be sent across the lines under flag of truce. But such letters often disappeared and were never delivered. Families divided by the war, or whose loved ones were held in enemy prisons, found the personals the only way they could send news.

Late in the war, many heartbreaking stories were contained in a few lines of type in the personals. “Amanda died, January 1, 1864,” read one advertisement in the Richmond Enquirer. “I am almost crazed. Break it softly to her mother.” On January 27, 1864, Michael Hammaker asked in the Richmond Enquirer about his son, Sergeant James P. Hammaker of the 50th Virginia, who was “captured or killed in the fight of Gettysburg. Any information of him will be thankfully received by his distressed parents.”

One Northern newspaper, the pro-Southern New York Daily News, made a specialty of placing personal ads for readers who wanted to send messages across the lines. Ads often added a conclusion such as “Richmond newspapers please copy” to ensure the intended recipient saw the message. Southern newspapers, particularly the Richmond Enquirer and other journals in the Confederate capital, obliged by reprinting the advertisements.

The Richmond Enquirer quoted rates for “communications between North and South” for “persons who wish to communicate with each other in regard to their health or whereabouts.” Each ad of eight lines or less cost two dollars, which included the cost of the newspaper printing replies when they were spotted in Northern papers. Patrons were urged to pay for at least five ads to increase the chances of the message getting through. By the late fall of 1863, issues of the Richmond Enquirer often contained two-thirds of a page filled with personals.

A library called the Confederate Reading Room opened on 11th Street in Richmond in October 1861. For 50 cents a month, patrons had access to newspapers from cities across the South. By early 1864 they carried Harper’s Magazine and other Northern papers, and even Punch and the Illustrated London News from across the Atlantic Ocean. January 1865 arrivals included files of several California newspapers and the Honolulu Commercial Advertiser.

In late 1864, the Confederate Reading Room purchased advertisements in the Richmond papers that listed people who had personals for them in the latest Northern papers. One ad, published in the Richmond Dispatch on September 20, 1864, named more than 30 people including some under aliases such as Pete, Col. A.J.I., and No. 259 Main Street.

Among the tragic stories of lost loved ones were at least a few more personals tied in with clandestine operations. Clement Claiborne Clay, a former U.S. senator from Alabama, joined the Confederate agents in Canada in 1864. He helped plan schemes such as Beall’s hijacking and Lieutenant Bennett Young’s famous Confederate raid on the banks in St. Albans, Vermont. Clay’s wife Virginia Tunstall Clay, who was staying in South Carolina, found that the personals were a more reliable way to contact her husband than the mails.

Clay used several aliases, with “T. E. Lacy” being one that he used in some of his secret correspondence as well as personal advertisements. Virginia Tunstall Clay’s 1904 memoir A Belle of the Fifties gave some examples of how the New York Daily News and the Richmond Enquirer let her keep in touch with her husband.

A message from “T.E. Lacy,” addressed to his brother, H.L. [Henry Lawson] Clay, was reprinted in the Richmond Enquirer on November 10, 1864. “I am well,” he said. “Have written every week, but received no answer later than the 30th of June.” Then, as the ad placed by Lacy continued his message, it revealed a potential danger of communication by classified ads: typographical errors. Virginia Clay quoted her husband’s message in her memoir as “Can I return at once? If not, send my wife to me by flag of truce, via Washington, but not by sea….” The Enquirer incorrectly rendered the passage as “Can I return at once? If so, send my wife to me.”

A message authorizing T.E. Lacy to return to the Confederate States, signed by H.L. Clay, appeared in the Enquirer on November 15. “Your friends think the sooner you return the better. At the point where you change vessels you can ascertain whether it is better to proceed direct or via Mexico. Your wife cannot go by flag of truce.”

The highest Confederate officials were involved in authorizing messages conveyed in the personals. In a letter, Henry Lawson Clay explained to his sister-in-law Virginia, “I consulted Mr. Mallory, Mr. Benjamin and the President” before placing the advertisement for November 15. Another ad directed to Clay on the same day was signed “B.P.J.,” which were perhaps the scrambled initials of Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin.

One month later, Clay acknowledged receipt of the communication from Richmond. Bearing the date of November 20, a reply from T.E. Lacy to H.L. Clay appeared in the Richmond Enquirer on December 15, 1864: “Yours and B’s received. Will try to leave, as suggested, by 1st of December, and may go to Mexico.” He continued, “Am very well; Bob and wife with me. He [is] improving.”

Clement Clay arrived in Charleston, via Bermuda, on the blockade runner Rattlesnake on February 4, 1865, and was reunited with his wife a few days later. After the end of the war, accused of involvement in the Lincoln assassination, Clay was held for nearly a year before his release in April 1866.

The growth of personals placed by Confederates and Southern sympathizers aroused suspicion and anxiety in the U.S. War Department. On January 22, 1865, the department acted. Maj. Gen. John Dix, commander of the Union’s Department of the East, which included New York City, threatened to arrest the editors of the New York Daily News unless they immediately halted all such advertisements. Interestingly, the War Department said nothing about help wanted or other types of classified advertisements, which apparently had also been used by spies.

The Confederate Reading Room was destroyed in the fires that raged through Richmond as the Rebel military evacuated the city on April 2-3, 1865. Lost in the building were extensive files of Confederate newspapers, some of which may have contained other hidden messages placed by Civil War spies that will never be brought to light.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments