By Victor Kamenir

When armed hostilities flared up between the Russian and Ottoman Empires in 1853 over control of holy places in Turkish-ruled Jerusalem, Great Britain was quick to throw its weight behind the Ottomans. For many years the British had been warily observing the Russian influence creep farther and farther south toward India, the crown jewel of the British Empire. When an opportunity to put the Russians in their place presented itself, the British did not hesitate to send in their troops. Not to be outdone, the French readily offered military contributions of their own.

The allies selected the Crimean Peninsula in southern Russia as their main objective. The port city of Sevastopol housed the Russian Black Sea Fleet, and its capture would virtually destroy Russia’s ability to project its power into the Mediterranean Sea. Before the Allies could establish iron-tight siege lines around the city, the Russian commander-in-chief in Crimea, Admiral Prince Alexander S. Menshikov, slipped the bulk of his ground forces out of Sevastopol. The British, French, and Turkish allies had barely enough troops to maintain porous siege lines around the city and keep Menshikov’s formidable field army at bay.

At the same time, the pressure from St. Petersburg was mounting on Menshikov to launch an attack on the allied forces and raise the siege of Sevastopol. Russian units from the Danube theater of operations began shifting to the Crimea. At the end of October 1854, two infantry divisions from the Russian IV Corps, under General Pavel A. Dannenberg, arrived to reinforce Menshikov. Unfortunately, Menshikov had little confidence in Dannenberg, who had lost a major battle to the Turks exactly one year earlier at Oltenitsa, Romania. Menshikov promptly wrote the commander of the Danube army, General Prince Nikolai Gorchakov, requesting Dannenberg’s recall. Gorchakov, however, wanted to be rid of the talentless Dannenberg as well. His reply to Menshikov was polite, but firm: “My dear Prince, you must take the good [reinforcement of two divisions] with the bad [Dannenberg].”

Considering himself sufficiently strong, Menshikov began planning an assault on allied lines in the vicinity of Mount Inkerman—although calling it planning would be a stretch. Menshikov’s headquarters staff could best be described as an entourage of courtiers rather than a collection of military officers. Headquarters did not even have any maps of the vicinity where the combat operations were to take place, giving upcoming events the less than flattering nickname, “the Battle Without a Map.”

“Aren’t They All the Same?”

Prince Menshikov held court over his glittering menagerie of hangers-on and military non-entities. It had been almost two centuries since Czar Peter the Great plucked the Menshikov family from its peasant obscurity into the highest strata of the Russian society. Immensely wealthy, well-educated, and narcissistic, Menshikov by his own admission was neither a politician nor a military commander. He began his military career in the Russian Army, fighting in the Napoleonic Wars. After reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel, Menshikov transferred to the Navy. On the eve of commencement of hostilities in 1853, he was appointed the czar’s emissary to the Ottoman Empire. It was a poor appointment, considering that Menshikov had been emasculated by a Turkish cannonball in 1828 and harbored understandable ill will toward the Ottoman Empire. His arrogant behavior during negotiations in Istanbul so infuriated and insulted the Turkish cabinet that it drove the Turks ever closer to war with Russia.

Menshikov considered being appointed commander-in-chief of all the Russian forces in the Crimean Peninsula as something merely due to one of his high stature. It appeared that his main goal in planning the operation was not to achieve success, but to avert blame in case of failure. After jotting down the bare outlines of the upcoming battle, Menshikov appointed the newly arrived commander of the IV Corps, Dannenberg, as the overall commander for the upcoming battle. When asked why he chose Dannenberg over other generals, Menshikov replied airily, “Aren’t they all the same?”

While the Russians planned, however desultorily, for the campaign, there was a strange feeling of lethargy within the British Army, particularly its commander, Fitzroy James Hewry Somerset, Also known as Lord Raglan. Despite numerous warnings about a major Russian attack, the British command did not expend much effort fortifying Mount Inkerman. A minor Russian attack on October 26 against the location was viewed as a mere skirmish, when in fact the Russians were probing the allied lines for a weak point. Unfortunately for everyone involved, they thought they had found one at Inkerman.

British Defenses at Mount Inkerman

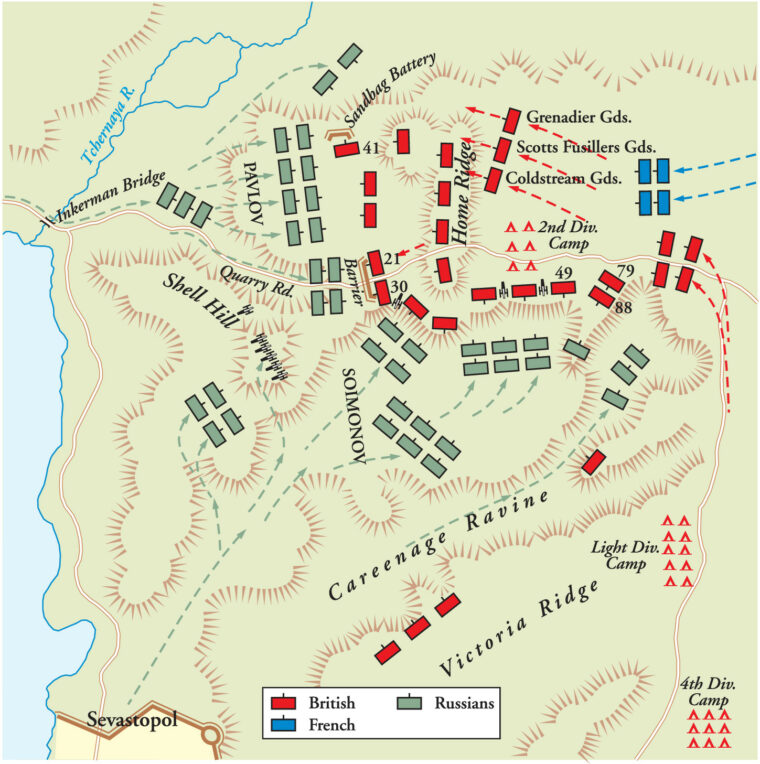

Located directly southeast of Sevastopol, Mount Inkerman was bordered by Careenage Ravine on the western side and the Chernaya (Black) River on the east. Quarry Road ran north from Balaklava across a dominating terrain feature called the Home Ridge. The British put up a four-foot-high stone wall somewhat grandly called the Barrier at the point where Quarry Road began descending Home Ridge. Another stone wall, this one approximately two feet high, ran along most of the northern face of the Home Ridge. Approximately a quarter of a mile north of the Home Ridge and slightly to the east, another stone barricade, this one nine feet high, was built. Called the Sandbag Battery, it was supposed to mount two cannon, neither of which was present at the time. As a further oversight, the builders of the Sandbag Battery had neglected to build firing steps for the infantry. About three quarters of a mile opposite the Home Ridge and slightly to the west was an elevation called Shell Hill, occupied by a few British pickets. Between Home Ridge and the Careenage Ravine to its west was the Careenage Plateau, criss-crossed with numerous shrub-covered gullies.

Menshikov had selected this area for his attack because he believed that by piercing the allied lines there and threatening enemy communications with their base at Balaklava, he could force the allies to lift the siege. Neither Menshikov nor Dannenberg prepared detailed plans for the upcoming attack—they merely offered suggestions. Generals F.I. Soimonov and P.I. Pavlov, who were to command the two main Russian assault columns, were left to make preparations largely on their own. “Attack the English position,” they were told, without being told exactly where to attack.

Instead of conducting a personal reconnaissance, Dannenberg, who was the overall commander of the upcoming assault, twice chose to visit Admiral Pavel S. Nakhimov, commander of the Russian naval forces. During the first visit, when Dannenberg apologized for not calling on him sooner, Nakhimov replied pointedly, “Think nothing of it, Your Highness. It would be better if you would have visited Mount Inkerman instead.” When Dannenberg showed up at his headquarters for the second time, Nakhimov had to practically kick him out to get his mind on the business at hand.

A Simple Plan of Attack

Considering that they were fighting in their own country, the Russian commanders seemed strangely unfamiliar with the area where the battle was to take place. On October 26, the day after the famous Charge of the Light Brigade through the “Valley of Death” at Balaklava, the Russians made a probing attack against Mount Inkerman. For some reason, the officers who participated in that attack weren’t even consulted in planning the attack on November 5. All dispositions were made as if they were to be conducted on the level ground—a ridiculous oversight. In truth, a multitude of small ravines, gullies, steep slopes, and large boulders clogged the area.

The overall Russian plans were fairly straightforward. Soimonov’s column, advancing from Sevastopol along the Careenage Ravine, was to ascend the Mount Inkerman plateau and rendezvous there with Pavlov’s column. Pavlov’s troops from Menshikov’s field army were to descend the Inkerman Heights on the north side of the Chernaya River, cross the river over the Inkerman Bridge, and climb the plateau. After the link up, Soimonov and Pavlov were to attack together and sweep aside the British by sheer weight of numbers. To support them, General Prince M.D. Gorchakov, the older brother of the Danube army commander, deployed near the ruins of the old Turkish Inkerman Fortress opposite the French. He was to make a diversionary attack to prevent the French from supporting the British. General N.D. Timofeyev, sallying out from Sevastopol, was to make a diversion on British left flank.

Mount Inkerman seemed like a good place to make a try at the allied lines since the numbers of British troops deployed there were small. The immediate area of the Home Ridge was defended by some 3,000 men of the British 2nd Division. After the division’s commander, Sir De Lacy Evans, fell ill one of the brigade commanders, Irish-born Brig. Gen. John L. Pennefather, took over command. Approximately one mile south of them was the 1,350-man Guards Brigade. Another mile farther south was the French Corps of Observation, commanded by General Pierre Bosquet and numbering approximately 10,000 men. Its mission was to protect the road junction leading to Balaklava. Almost 7,000 more British troops in parts of three divisions, the 3rd, 4th, and Light, were posted just west of the 2nd Division, but separated from it by multiple ravines and brush-covered slopes.

The Assault on Shell Hill

Around 5 am on November 5, Soimonov’s column slipped out of Sevastopol. This force of roughly 19,000 men and 38 guns began climbing the muddy slopes, its right flank secured by the Careenage Ravine. At approximately the same time, Pavlov’s column of 16,000 men and 96 guns advanced on Mount Inkerman from the northeast. Gorchakov, with his 22,000 men and 88 cannon, was already in place on the far right of the allied line, facing the French.

Incredibly, no one had bothered to check the Inkerman Bridge over which Pavlov’s column was to cross. The bridge was in such a state of disrepair that two valuable hours had to be wasted repairing it before large bodies of troops could safely traverse it. Soimonov, attacking almost on schedule, went in unsupported by Pavlov. It had rained almost nonstop for the previous 24 hours, and the slopes of Mount Inkerman were muddy and slippery, making the Russian ascent slow and difficult. Dense fog clung stubbornly to gullies and thickets. Nearly invisible in their gray overcoats against the background of gray fog, the Russian columns were almost on top of the the British outposts before they were spotted. First shots announced the coming of a long and bloody day. British soldiers, armed with quick-firing Minié rifles, put up a large volume of fire as they grudgingly gave ground under the weight of the Russian columns.

Alerted by the commotion, British commander Lord Raglan rode up to the Home Ridge around 7:30 am. Even though the thick fog largely obscured the majority of the developing battlefield, he quickly appraised the situation and ordered up reinforcements from the 4th Division and the Guards Brigade. Raglan could see that the Russians were already on Shell Hill and became concerned about the Russian guns that would surely be emplaced there. To counteract the Russian guns, the British commander ordered two 18-pounder guns from the siege park moved to the Home Ridge.

Raglan was correct to worry. Soimonov immediately placed 22 12-pounders on Shell Hill and opened fire in the general direction of the British positions. Even though the fog largely obscured the British dispositions, numerous Russian shells soon began exploding among the tents of the 2nd Division’s base camp. The Russian artillery created havoc among British supply train horses and pack mules, killing scores of the animals. To minimize his casualties, Pennefather moved the bulk of the 2nd Division down the forward slopes. Seeking to buy time for reinforcements, he began feeding his companies piecemeal into the forward skirmish line. “Whenever you see a head, hit it,” he advised somewhat unhelpfully.

After placing approximately half of his force in reserve behind Shell Hill under Maj. Gen. O.P. Zhabolyutski, Soimonov personally led the rest forward. Encountering rough terrain, large Russian battalion-strength columns began to fracture into small elements, each crawling independently through numerous ravines up to the British positions. Even though Pennefather’s men were outnumbered 3-to-1, they unleashed such a furious and deadly fire that the Russian columns were brought to a halt. Within the first 30 minutes of the fight, both Soimonov and his second-in-command fell dead, picked off their horses by British sharpshooters, Throwing the disorganized force into confusion. The Russian officers customarily led from the front, and this reckless bravery resulted in disproportionate numbers of officers becoming hors de combat. Wavering without instructions, Zhabolyutski would not commit any of his reserves without Dannenberg’s personal approval.

At first, only two British 9-pounders supported the infantry. Soon, however, a six-gun British battery deployed at the head of a large gully and added its weight to the chaos. A small Russian column, charging out of the dead ground, rushed the battery and captured three cannon. British gunners bravely fought with swords and rammers to defend their pieces, but were cut down almost to a man near their guns. Bulling forward, the Russians began forcing back part of the 49th Regiment, only to be attacked in turn by four companies of the Connaught Rangers, the largely Irish 88th Regiment of the Light Division. Another British regiment with more guns, the 77th Foot, arrived to help restore the British line on the Home Ridge. By 8 am, Soimonov’s column, now a mob of intermixed units, began to ebb back to Shell Hill.

Battle over the Sandbag Battery

Thirty minutes later, Pavlov’s column appeared on the scene, having been delayed at Inkerman Bridge for two hours. His forward unit, the Taroutin Jaeger Regiment, quickly captured the Sandbag Battery after driving off a small picket from the British 55th Regiment. Another Russian Jaeger regiment, named after the famous battle at Borodino, ran into more men of the 55th and part of the 30th Regiment. The British tried to pour a volley into a dense Russian column, but damp cartridges misfired in their Minié rifles. Undeterred by the weak volley, the 30th Regiment led a bayonet charge that forced the Russians to retreat down the slope. Another British regiment, the 41st, smashed into the Taroutin Jaegers and forcibly ejected them from the Sandbag Battery.

The second echelon of Pavlov’s column, composed of the Okhotsk, Selenginsk, and Yakoutsk Regiments, bore hard on the British right, retaking the Sandbag Battery. In turn, the Russians were counterattacked by riflemen from the Light Division and one of their regiments, Yakoutsk, was driven back. As the ebb and flow of battle developed, an undefended breech began opening in the British line. Reformed, the Yakoutsk Regiment began advancing into the gap between the Sandbag Battery and the Barrier. A brigade from the 4th Division plugged the gap in the nick of time. The British Guards Brigade attacked the Sandbag Battery and retook it after some heavy bayonet work. The Russian Okhotsk and Selenginsk Regiments, losing men at every step, continued launching themselves against the British Guards. Manchester-born Timothy Gowing of the 7th Royal Fusiliers described the action around Sandbag Battery: “On came the Russians,” he wrote. “The bayonet was used with terrible effect by all regiments. The enemy, driven on by their brave officers, had to—and did literally—climb over heaps of their slain countrymen and ours to renew this bloodthirsty contest; but they had to go back time after time much quicker than they came.”

As the British casualties at the Sandbag Battery mounted, the commanding general of the 4th Division, General Sir George Cathcart, personally led elements of two British regiments against the Russian left. Descending into a narrow ravine, Cathcart’s force suddenly saw a body of men appear on the slope above them. The thick fog prevented their identification until they poured down a musket volley into the British ranks. Thinking that they were being fired upon by their own side, Cathcart ordered his men to remove their greatcoats so that their red coats would be visible. Still, the fire from above continued to rain down upon them. Without further hesitation, Cathcart turned his men around and led them up the slope at the Russians. Now the muddy slopes handicapped the British. The withering fire decimated the British ranks, with Cathcart being among the first to be killed, shot through the heart. His adjutant Charles Seymour, son of a former British ambassador to St. Petersburg, fell dead at his side. A few pitiful survivors of Cathcart’s force managed to fight their way to safety.

At this critical juncture, elements of two more British regiments arrived to reinforce the beleaguered Guardsmen at the Sandbag Battery. On their heels came two full French regiments led by Bosquet himself. The two heavy 18-pounder cannon that Lord Raglan had ordered up earlier finally went into action around 9:30 am. Soon, the heavy British cannon began silencing the Russian guns on Shell Hill. The combined force of British and French began pushing the Russians down the ravines, rescuing some of the British troops who had been cut off earlier.

“We Are [Screwed].”

Around 10 am, Timofeyev launched his prearranged sally from Sevastopol. Even though his force consisted of only four battalions of the Minsk Regiment and four light cannon, they attacked with such élan that strong French reserves had to be shifted to meet them. Stubbornly giving way, Timofeyev retreated back toward Sevastopol. The French troops, impetuously pursuing him, came within the range of Russian guns in the city and had to fall back after losing a number of men, including one general killed.

While the fight with Timofeyev raged, Bosquet was told that an attack was developing against the road to Balaklava. With the Russian troops crawling all over the Inkerman Plateau, a strong attack toward Balaklava would have shuttered the British positions. When the French commanding general on the scene, General François Canrobert, conferred with Raglan in person and relayed to him the rumored new development, Raglan said in no uncertain terms, “We are [screwed].”

Luckily for the allies, the Russian attack on the far right of the French position in the Balaklava valley was only a feint. While not budging with his main force, Gorchakov released his advance guard under Maj. Gen. Pavel Liprandi to make a diversionary attack against the French forward positions. Consisting of only a few regiments, Liprandi’s attack was no more than a pinprick. However, it did delay movement of further French reinforcements while Bosquet sorted things out. The hard-pressed British, seeing the French forces falter, almost lost hope. Colonel Somerset Calthorpe, Lord Raglan’s nephew and aide-de-camp, described the scene: “I cannot describe to you the sinking sensations one felt on observing our allies give way,” Calthorpe recalled. “Our first impression was that they had retired, beaten back by the overpowering masses of Russian infantry. I confess myself that I thought the day was lost.”

A Soldier’s Battle

The heavy pressure on the Home Ridge continued. Dannenberg again and again personally led his regiments against the British position. Casualties were heavy on both sides. The British Minié rifles proved to be the great equalizer. Their higher accuracy and faster rate of fire allowed the British to negate the larger numbers of their Russian foes. The thick fog equally hampered and aided the both sides. The British did not realize just how severely they were outnumbered, and the Russians did not know just how few British were opposing them. The irregular nature of the terrain broke up larger formations into small groups, each fighting individual battles among the rain, fog, and thickets. The narrow gullies and ravines limited the number of men that could face each other at one time, and the larger numbers of Russians could not be effectively brought to bear on the British.

It was truly a soldiers’ battle. The units became splintered, intermixed, and confused. In some places there were no cohesive battle lines, only pockets of British and Russians furiously hacking at each other in the mud. Officers were effectively reduced to commanding the immediate vicinity around them. Generals commanded battalions, colonels led companies, lieutenants and captains fought sword in hand alongside their men. Lt. Col. Edward Hamley of the 1st Division described the weltering confusion: “On our part it was a confused and desperate struggle. Colonels of regiments led on small parties, and fought like subalterns, captains like privates. Once engaged every man was his own general.”

The 2nd Division was leaking its lifeblood onto the rocky, muddy slopes. The British 41st and 95th together could only muster 64 men after the battle. The whole of the 2nd Division had less than 300 men remaining in ranks at the end of the day, commanded by a major. The Guards Brigade’s casualties ran almost 50 percent. The Russian units were suffering appalling casualties as well. Soimonov’s column lost over half of its officers. Every time a disordered Russian unit would pull back, its officers would rally the men and fling them back at the British. Shockingly, almost Dannenberg held back 12,000 men from Soimonov’s and Pavlov’s columns in reserve behind the Shell Hill. These fresh regiments might well have shattered the British line, which was cracking in many places. Instead, they stood motionless, listening to the furious battle raging within arm’s reach. Similarly inexcusable, Gorchakov’s 22,000 men stood idle as well. A man of unquestionable personal bravery, Gorchakov proved incapable of independent command. Had he exerted even some pressure on the French, they would not have been able to help the British.

The Russian Retreat

While Gorchakov’s column did nothing, the French began shifting more and more units to reinforce the British line. One such regiment, the 7th Light, came up to reinforce Pennefather, but immediately came under concentrated fire from Russian artillery and had to fall back. The Russian infantry pressed hard against them, and a breech began to develop in the allied line. Parts of several British regiments rushed forward to stabilize the line along the Barrier. The Russians reformed and charged again, but the scratch force of British regiments stood their ground. The dead were stacked in heaps several high, a grim testimonial to the bravery and tenacity of both the British and Russian soldiers. The British line held.

Meanwhile, the British 18-pounders were proving successful in their use of counterbattery fire against the Russian guns on Shell Hill. The rate of fire of the Russian guns slackened as more and more guns were knocked out by the heavier British cannon. A number of British infantrymen also turned their fire on Russian gunners. The Superior range and accuracy of British rifled muskets played havoc on the Russian gun crews.

Reluctantly realizing that nothing more could be done, Dannenberg ordered the army to retreat. Around noon, the Russian infantry began disengaging everywhere and retreating to their starting positions. Several French artillery batteries set up on a small hillock and began blasting gaps in the calmly retreating Russian ranks. Two Russian steamships, Vladimir and Khersone, armed with cannon, moved up to Inkerman Bridge and engaged the French guns. Their effective fire forced the French artillery to pull back. At the same time, engineering Colonel E.I. Totleben, who had designed the defenses at Sevastopol, organized a scratch force of parts of two Russian regiments to keep back the aggressive French skirmishers.

Bloodied, beaten, but not demoralized, the Russians pulled back in good order. By 2 pm, the Russian forces had disengaged at all points. The firing petered out. The bloody battle, perhaps the last purely hand-to-hand battle in military history, ended up not with a bang but a whimper. Both sides resumed the long siege of Sevastopol, which lasted another 10 months until the Russian garrison finally surrendered on September 8, 1855.

Aftermath

Almost immediately after the last shot was fired at Inkerman, the discredited trio of Menshikov, Dannenberg, and Gorchakov began pointing fingers at one another. Fortunately for them, Soimonov had conveniently gotten himself killed, and a large portion of the blame was heaped on the one man among them who had made the supreme sacrifice. This was the last time during the Crimean War that the Russian forces would achieve numerical superiority over their opponents. However, the excellent opportunity to dramatically change the course of events was wasted due to timidity and disorganization on the part of the senior Russian commanders. While all of the available British troops, just short of 12,000 men, and approximately 5,000 Frenchmen were committed into the fight, less than 30,000 men out of available 60,000 Russians directly participated.

In British military history, the Battle of Inkerman quickly took its place as a shining example of the famed tenacity of the British soldier fighting against overwhelming odds. Had the Russian commanders committed all their available forces, the odds against the British would have been simply daunting. As it was, the “thin red line of heroes” once again had held fast. Meanwhile, the stoic Russian soldiers were unfairly maligned after the battle by Menshikov, who claimed that his men did not fight bravely enough. Almost immediately, the senior Russian commanders who had fought at Inkerman came to the defense of their men, disavowing any claims of their cowardice. But the Russian rank-and-file did not need anybody to tell them how well they had fought. They knew.

As for the British soldiers in the ranks, Queen Victoria uncharacteristically exerted herself to praise their efforts. The Duke of Newcastle, the English secretary of war, passed along word to Lord Raglan that “the Queen desires that you will take measures for making known her no less warm approval of the services of all officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers who have so gloriously won by their blood, freely shed, fresh honors for the army of a country which sympathizes as deeply with their privations and exertions as it glories in their victories and exults in their fame. Let not any private soldier in those ranks believe that his conduct is unheeded. The Queen thanks him—his country honors him.”

The night after the battle was clear, the fog and the rain which for so long had tormented the combatants having finally dissipated. The moonlit slopes of Mount Inkerman were covered by mangled bodies of Russian, British, and French soldiers. Over 12,000 Russians had fallen, dead or wounded, along with 3,400 British and 950 Frenchmen. The medical personnel and stretcher parties of both sides who roamed the area said later that it seemed as though the mountain itself was groaning. French General Bosquet, no stranger to combat, summed up the battle most fittingly. Looking down at the British, French, and Russian bodies piled atop each other around the Sandbag Battery, he covered his nose with a handkerchief and muttered, “Quel abattoir! [What a slaughterhouse!]”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments