By Michael E. Haskew

Paris was in tumult. The French 2nd Armored Division had rolled into the City of Light on August 25, 1944, ending four years of harsh Nazi occupation. A great parade was set for the following day, a celebration of France’s deliverance, and foremost among its participants was to be Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the Free French movement and the soul of the broken nation during its darkest days of humiliating defeat.

De Gaulle had followed General Jacques Leclerc and the 2nd Armored Division into the French capital, carefully choreographing the manner in which he would assert control of the government. Although he held a reasonably solid base of support among the Resistance, the armed forces, and the people, he realized that the end of Nazi dominion might prompt rivals to assert themselves, possibly even plunging the nation into civil war.

Upon entering the city, de Gaulle first went to the war ministry, then to the main police station to solidify the cooperation of the gendarmerie. A brief, matter-of-fact meeting with Resistance leaders followed—all this as his Gaullist representatives throughout the liberated areas of the country secured the support of local and regional leaders.

Sometime after 8 pm, he stepped out onto the small balcony of the Hotel de Ville (City Hall) and greeted tens of thousands of Parisians who had been gathering and waiting for several hours to catch a glimpse of the perceived savior of France.

The next day, the parade commenced, with a million people lining the Champs Élysées. Walking in uniform to the Place de la Concorde, de Gaulle was flanked by prominent associates and others who had fought and bled for this occasion, carefully placed in the procession so that the identity of its leader was unmistakable.

In his postwar memoirs, de Gaulle remembered, “So, I walked on, quiet and deeply moved in the midst of the crowd’s indescribable exultation, through a storm of voices that echoed my name. At that moment there was occurring one of those miracles of national consciousness, one of those gestures on the part of France that in the course of centuries sometimes come to light in our history. And I, in the middle of this passionate outburst, I felt that I was fulfilling a function that went far, far beyond myself personally, that of acting as the instrument of destiny.”

When he reached the Place de la Concorde, de Gaulle got into a car for the short ride to the Cathedral of Notre Dame, where a service of thanksgiving was to be held. As he exited the vehicle, two young girls presented him with bouquets of spring flowers. Suddenly, the reports of rifle fire were heard in the street. Extricating himself from the crowd that had pressed him against the door of the cathedral, de Gaulle entered. Then, another rifle shot rang out—this time from high in the choir loft. Apparently with only disdain for the gunfire, he strode the 200 feet down the aisle to his seat.

A British Broadcasting Company (BBC) observer was one of numerous witnesses who were astonished at this display of coolness under fire. He reported that de Gaulle “walked straight ahead in what appeared to me to be a hail of fire, without hesitation, his shoulders flung back. It was the most extraordinary display of courage that I’ve ever seen.”

Another bystander was heard to say that the incident confirmed the fact that de Gaulle held the nation of France in the palm of his hand.

Of course, the de Gaulle ascendant had not come to such high stature without great struggle. In fact, he was well acquainted with trial and tribulation. However, he had never waivered from the conviction that his destiny and that of France were intertwined. Even as a young boy, born on November 22, 1890, in the industrial city of Lille at the height of the Belle Epoch, a period of tremendous cultural revival in France, he was certain that his future held great promise, that he was fated to render some noble service to his country.

The son of Henri and Jeanne Marie de Gaulle, Charles was raised as a devout catholic. The third of five children, four boys and a girl, his father was a lifelong educator. Never one to conform, it was somewhat surprising that he chose a career in the military with its tradition of regimentation and rigid chain of command. Perhaps it was that spark of destiny within that drew him to the Army and the military academy at St. Cyr.

There were more than 800 applicants to the prestigious French military academy, and 221 were accepted. Charles had studied tirelessly and was among the select few. There was a significant prerequisite. Prior to entering St. Cyr, each officer candidate was required to spend one year in the enlisted ranks of the French Army. Dutifully, on October 10, 1909, he joined the 33rd Infantry Regiment headquartered at Arras, not far from his hometown.

The enlistment was the beginning of a lifetime of love and hate with the French military. When his year was up, Charles had reached the rank of corporal. His commanding officer had had enough of the headstrong soldier who always seemed to know more than the veterans and refused to advance Charles further in rank. “What use to make that young man a sergeant when the only military title that would interest him would be Grand Constable,” said the weary captain.

Despite that, in the autumn of 1910 Charles entered St. Cyr. Initially, his academic effort was unremarkable, and on one of his papers a professor wrote sarcastically, “Average in everything except height.” The tall, thin figure remained aloof, most often apart from the body of his fellow cadets. Along with the nickname of “Grand Constable” that followed him from the 33rd Regiment, he also became derisively known as “The Big Asparagus” and “Le Coq.”

By the time he graduated in October 1912, a revived commitment to his studies had landed Charles 13th in a class of 211. Along the way, though, he had freely questioned authority, debated with instructors, and generally developed the reputation of a headstrong maverick. Nevertheless, the official assessment of his performance was positive and noted, “A very highly gifted cadet. Conscientious and earnest worker. Excellent state of mind. Calm and energetic nature. Will make an excellent officer….”

Curiously, de Gaulle chose to return to his old 33rd Infantry Regiment after graduation. At the time, its commanding officer was Colonel Philippe Pétain, destined to become a Marshal of France and national hero in World War I, only to tarnish his legacy with the stain of Vichy collaboration with the Nazis in 1940. The two would forge a long friendship, and on more than one occasion Pétain was willing to use his prestige to bail de Gaulle out of hot water.

Since the humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, every career officer in the French Army was convinced that another war with Germany loomed. That war came in the summer of 1914.

The holocaust of World War I convinced de Gaulle more than ever that he was a man of destiny. His baptism of fire occurred on August 15, 1914, during the fight for a bridge across the Meuse River at the French town of Dinant. He was wounded in the right leg while leading his infantry platoon against German machine guns, and the grueling recovery took seven months.

In the winter of 1916, de Gaulle and the 33rd Regiment were transferred to the killing fields at Verdun, and there the young officer, now a captain with the Croix de Guerre on his chest for bravery, nearly lost his life again. When the French line was breached on March 2, de Gaulle and a handful of soldiers made a heroic stand, but he was seriously wounded and taken prisoner. Most Frenchmen who survived the ordeal, including his commanding officer, presumed de Gaulle had been killed.

“I had hardly gone 10 meters when I came on a group of Boches crouching in a shellhole,” he recalled later. “They saw me at the same moment, and one of them ran his bayonet into me. The thrust went through my map case and wounded me in the thigh. Another Boche shot my orderly dead. Seconds later a grenade exploded in front of my face, and I lost consciousness.”

During 33 months as a prisoner of war, de Gaulle remained a thorn in the Germans’ side, attempting to escape five times and actually remaining at large with a co-conspirator for several days. While in prison at Ingolstadt, he was joined by Roland Garros, the inventor of a mechanism that allowed machine guns to fire forward from the cowling and through the propeller of an airplane, revolutionizing aerial warfare, and Mikhail Tukhachevsky, a Russian officer who achieved the rank of marshal and later fell victim to the Stalinist purges of the Red Army officer corps in the 1930s.

Following the 1918 armistice and a brief reunion with his family, Charles attended a course for French officers who had been prisoners of war. Its purpose was to acquaint these men with technological developments and other aspects of modern warfare that had emerged while they had been prisoners. While attending the course, he awakened from a deep depression and overcame the belief that his military career was finished.

During 1919-1921, Charles was detailed with 2,000 other French officers as an adviser to the army of a newly reconstituted Poland, fighting the army of Bolshevik Russia. For bravery under fire, he was awarded the Polish Virtuti Militari. He declined an invitation from the Polish government to lecture at its Army staff college, returning to France and his fiancée, Yvonne Vendroux, whose family owned a biscuit-making factory in Calais. They were married on April 7, 1921, and remained together for the next half century. They had three children, Philippe, born in December 1921, Elizabeth in 1924, and Anne, born with Down Syndrome, in 1928.

Charles taught at St. Cyr for a year while endeavoring to gain entry to the École Supérieure, the prestigious Army war college. For any French officer aspiring to the higher echelons of command and responsibility, graduation from the École Supérieure was a necessity. Others had amassed more extensive combat records while he languished as a prisoner. He had not been a member of the general staff and was not guaranteed a place in the upcoming class. However, based on his high score on the competitive examination, he gained entry in the spring of 1922.

Preceded by his reputation as a difficult pupil at St. Cyr, an arrogant know-it-all, and as the protégé of Pétain, de Gaulle entered the war college as something of a marked man. In fact, those who had never met him were likely to have already formed a negative opinion of the young officer. True to form, he did not disappoint and argued with instructors and senior officers to the extent that when graduation came he was given a final rating of “Good” rather than the “Very Good” that was probably deserved.

It was a slight that neither de Gaulle nor Pétain ever forgot. Following an assembly during which his rating was read aloud, de Gaulle seethed, “I will come back to this dirty hole only when I am commandant of it. Then you will see how things will change.”

Adding insult to injury, de Gaulle was posted to the Fourth Bureau Army in occupied Germany, stationed in the city of Mainz, and placed in charge of refrigeration, storage, and the supply of food. It was career oblivion. Within nine months, though, Pétain rescued him from the dead-end job and brought him to Paris to work as a writer on a history of the French soldier in wartime.

Pétain further arranged for de Gaulle to deliver a series of lectures to the esteemed faculty at the École Supérieure, a captive audience, many of whom had a hand in de Gaulle’s humiliation with the undeserved rating. The lectures were sweet revenge, a lowly captain, not yet confirmed for promotion to major, delivering superb oratory to officers quite senior in rank but compelled to swallow their rage.

For de Gaulle, a man of towering ego and great intellect, the moment was sublime, even in later years. It was, though, soured years later by the irreparable rift that developed between de Gaulle and Pétain over the rights to the material from the book to which Charles had contributed as a ghost writer under Pétain, and further damaged by Pétain’s willingness to collaborate with the Nazis. After World War II, the disgraced old marshal had a death sentence commuted to life in prison by de Gaulle and was exiled to l’Ile d’Yeu where he died in 1951 at the age of 95.

Throughout his life, de Gaulle was a prolific and accomplished author. He wrote dozens of books and articles, including extensive memoirs and treatises on various topics. Among these topics were leadership, historical perspective, and a new weapon, the tank, which he had become aware of while still a prisoner of the Germans during the Great War. He read the works of British armor advocates B.H. Liddell Hart and J.F.C. Fuller, advocated a standing, mechanized army of 100,000 trained professional soldiers, and argued for the formation of armored divisions within the French military.

He argued, however, at his own peril. In the wake of World War I, the French military establishment was decidedly defensive minded. The tank, many high-ranking officers believed, was an offensive weapon. De Gaulle refused to be dissuaded and made enemies of numerous influential officers. One of these was General Maurice Gamelin, commander-in-chief of the Army.

“I do not believe in Colonel de Gaulle’s theories,” Gamelin fumed. “They are unsound and unrealistic. Tanks are necessary, it is true. But to think that with tanks you can crush the whole organization of the enemy is just not serious…. The tank is not endowed with self sufficiency. It has to go through, but it has to come back for more fuel and ammunition. As for the air force, it will be a flash in the pan.”

In the autumn of 1936, de Gaulle’s promotion to full colonel was blocked by the vindictive Gamelin and, as a 46-year-old lieutenant colonel, the upstart officer took command of the 507th Tank Regiment the following year. It was de Gaulle’s first practical experience with tanks, and he earned yet another nickname—“Colonel Motor.”

At the same time, the relationship between de Gaulle and his benefactor, Pétain, collapsed. After years of benign neglect, the great work that Pétain had undertaken on the history of the French soldier, Le Soldat, lay unfinished. De Gaulle decided to use seven of the 10 chapters he had ghost written in his own forthcoming book, La France et Son Armée. The two were unable to agree on ownership of the rights to the material, and barely another word ever passed between them.

When the storm of World War II broke across Europe with the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, the firepower and rapid mobility of the German panzer formations stunned the world. Within months, Hitler turned his blitzkrieg westward. On May 10, 1940, the Nazi juggernaut attacked France and the Low Countries. Although it remained decidedly defensive minded, depending on the fixed fortifications of the Maginot Line to dissuade an invasion of the country from the east, the French Army did approve the formation of two armored divisions in December 1938. However, the army’s first armored brigade was not authorized until September 2, 1939, the day after the opening of hostilities.

By the middle of May, Gamelin had summoned de Gaulle to his headquarters, told him that the number of authorized armored divisions had been increased to four, and that with the relatively low rank of colonel he would be given command of one of these—although it existed largely on paper only.

Woefully short of men, vehicles, and tanks, de Gaulle moved the 4th Armored Division forward as seemingly endless lines of refugees and despondent soldiers who had thrown their weapons away trudged in the opposite direction. On May 17, elements of the 4th Armored Division engaged the Germans near the village of Montcornet, a crossroads town that lay in the path of the Germans headed across the Meuse River and on to the English Channel.

About 120 Germans were taken prisoner, while 25 French soldiers were killed and 23 of their precious tanks destroyed. The intent had been to delay the German advance but, as the afternoon wore on, German Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers attacked, compelling a withdrawal.

Despite the realization that the Battle of France was lost, the 4th Armored Division continued to resist. On May 21, de Gaulle was promoted to the temporary rank of brigadier general, and his command was ordered to move 150 miles west to contest the German advance near Abbeville.

A week later, the division fought a three-day battle, attempting to dislodge the Germans from a bridgehead across the Somme River. Accounts vary; however, it cannot be disputed that de Gaulle exhibited bravery under fire and blunted the German advance for a time. Casualty figures are vague, with anywhere from 250 to 400 Germans taken prisoner and French tank losses estimated at 70 to 130. Relieved by the British 51st Highland Division, the battered French withdrew.

One of the few members of the French National Assembly who shared similar views on several topics with de Gaulle, Paul Reynaud had assumed the post of prime minister in March. Doing his political best to contain the rising defeatist sentiment among French politicians and senior military commanders, Reynaud appointed de Gaulle on June 6 to the position of Undersecretary of State for National Defense.

Reynaud made the appointment over the strenuous objections of both Pétain and General Maxime Weygand, an old adversary who had replaced Gamelin in overall command of the French Army. A career soldier, de Gaulle entered the political arena and remained engaged in it for the next 30 years.

A wave of shuttle diplomacy followed as de Gaulle made several trips to London, met British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and labored with Reynaud to keep France fighting as the Germans indeed reached the English Channel and the howls of those clamoring for parlay with the Nazis grew louder. There was talk of removing the government to the French colonies in North Africa to continue the fight, and the government did relocate to Bordeaux just ahead of the Nazi vanguard, which had marched into Paris on June 14, 1940.

A new French government was established with Pétain at its head, and a humiliating surrender was forced upon the defeated nation in the same rail car in which the Germans had capitulated at the end of World War I. To make the humiliation complete, Hitler ordered the rail car removed from a museum and transported to the forest of Compiegne, where the German surrender had taken place two decades earlier. The national nightmare of Vichy collaboration followed.

As for de Gaulle, the British diplomats took note of the dour Frenchman who had not seemed to exude the air of defeatism that most of his countrymen shared. In one meeting, Churchill had observed the tall brigadier, and when the discussions were over, he moved across the room and whispered to de Gaulle, “L’homme du destin (the man of destiny).”

De Gaulle was now at a personal crossroads. It was no secret that he vehemently opposed the surrender and collaboration with the Nazis. He no longer held a post in the French government, and as an Army officer he was subject to the vengeance of Weygand. Pétain probably had ordered a search for him and would likely place de Gaulle under arrest. Therefore, he saw to the safety of his family as best he could and decided to fly to London.

De Gaulle visited Reynaud at Bordeaux and was given all that remained in the French treasury, 100,000 francs, about $500. The following day, June 17, accompanied by British diplomats and his aide, Geoffrey de Courcel, Charles de Gaulle left France and looked to an uncertain future. He had little money, no political standing, no army, and no country. Churchill observed later that there was one thing of great importance in the brigadier’s possession. “De Gaulle,” he said, “carried with him, in this small airplane, the honor of France.”

Churchill welcomed de Gaulle in London, and the following day the French exile spoke to his dazed and confused countrymen via the BBC. In what has come to be known as the Appeal of June 18, he exhorted them to continue to resist. “I, General de Gaulle, now in London, call on all French officers and soldiers now present on British territory or who may be so in the future, with or without their arms … to get in touch with me. Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and will not be extinguished….”

Then, he waited. In fact, he attempted to contact French officers who were his senior, asking them to take command of the movement in London and asserting that he would follow them if they would step forward. No one did. At the end of June, Churchill called de Gaulle to his residence and said bluntly, “You are all alone. Well then, I recognize you alone.”

While de Gaulle was organizing the Free French movement, the Vichy government tried and convicted him twice in absentia, first of disobedience and then treason, stripping him of his French citizenship, and sentencing him to four years in prison and later to death. It mattered not to de Gaulle; he was the soul of France. The true France was with him, and the imposter of Vichy was certain to come to grief.

During the next four years, the vexing relationship between Churchill and de Gaulle waxed and waned. Further complicating matters, the Americans were not at war until December 7, 1941, and considered Vichy the legitimate government of France for some time. The administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt mistrusted de Gaulle and struggled with the fact that a representative of a defeated country could be so obstinate and uncooperative while his allies did their utmost to liberate his country from the Nazis.

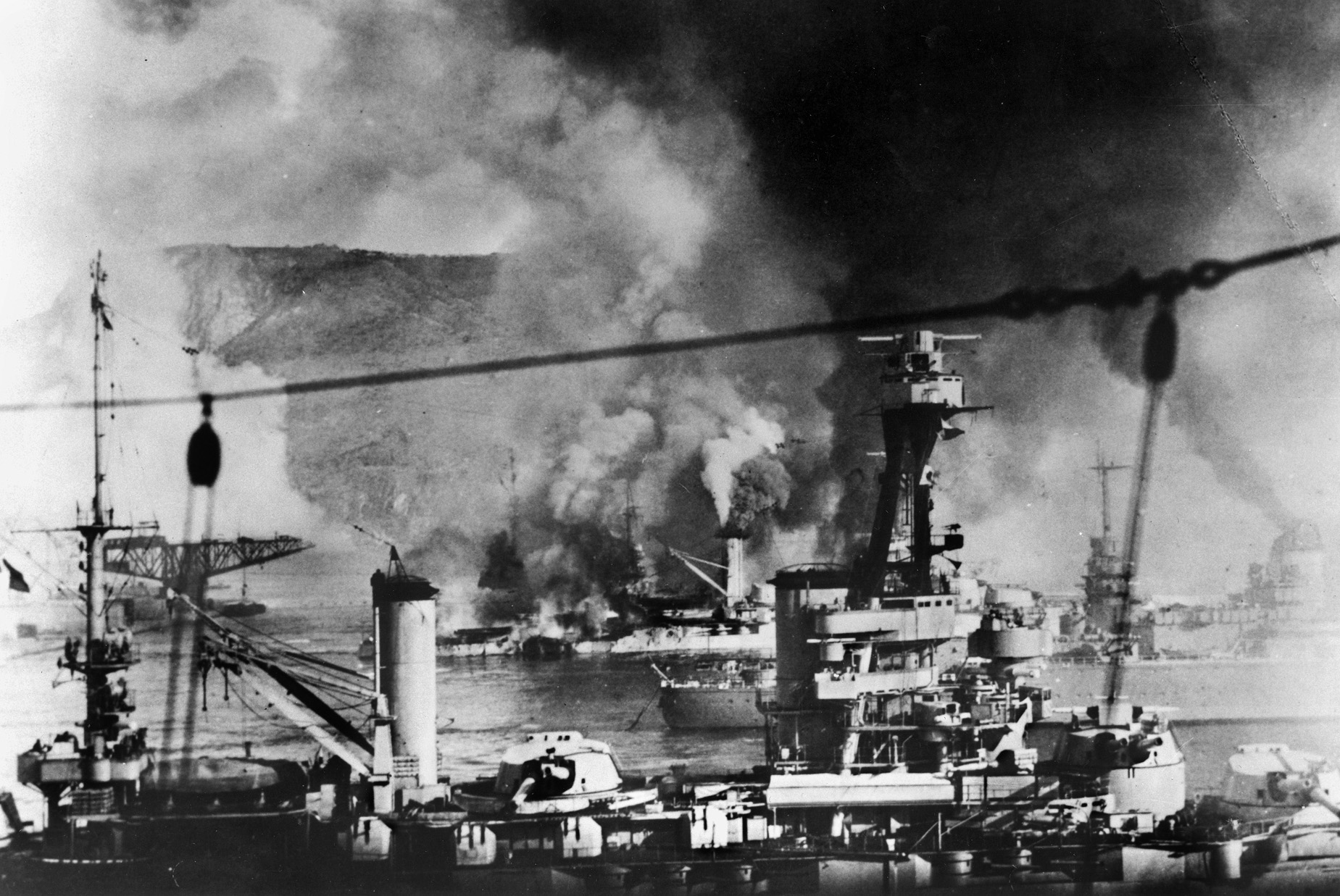

De Gaulle was initially aghast when the British Royal Navy was ordered to fire on the French Fleet at Mers el-Kébir in July 1940 to prevent these warships falling into German hands. More than 1,300 French sailors were killed. However, he understood the British action and spoke to his grieving countrymen over the BBC. His power and influence continued to grow as French colonial governments in Africa and the Pacific rallied to him.

In September, an abortive British-Free French attempt to capture the Vichy port of Dakar, Senegal, so embarrassed de Gaulle that he contemplated suicide or simply fading away to a quiet life in Canada. Neither, it turned out, was an appropriate course of action for the man whose soul was bound to the destiny of France.

One of the most fractious incidents during the war years occurred during preparations for the invasion of North Africa, Operation Torch, on November 8, 1942. The governments of Britain and the United States hoped for a quick surrender by Vichy authorities in North Africa. Churchill and Roosevelt concluded that the Free French were not to be included in the landings and that de Gaulle was not to be informed about the impending operation.

When he was finally told of the landings on the morning of November 8, de Gaulle raged, “I hope the Vichy people will fling them into the sea! You can’t break into France and get away with it!” Churchill did his best to settle de Gaulle down with reassurances of continuing support for the Free, or Fighting French, movement as it was renamed in June of that year.

As de Gaulle continually sought to maintain the French seat at the table of world politics and to assure that the country would be looked upon as a great power after the war, both the British and American governments remained wary and considered much of his posturing as detrimental to the Allied war effort.

The Americans subsequently proposed a more agreeable leader for the resurgent France and offered up General Henri Giraud as a successor or at least a buffer to the irascible de Gaulle. A tense meeting at Casablanca in January 1943 produced a few awkward photos, including one of the Frenchmen shaking hands, but little else. As events unfolded, the astute de Gaulle politically outmaneuvered Giraud and marginalized his rival with little difficulty.

As preparations for the Normandy invasion of June 6, 1944, progressed, Roosevelt was adamant that de Gaulle was to be kept out of the detailed planning. Just two days before the invasion, de Gaulle was briefed on the tactical situation and the objectives of the initial operation. For his part, de Gaulle had no interest in discussing a joint plan for the government and administration of a liberated France. Without question, France would be governed by the French people—with de Gaulle at their head—once the Germans were defeated.

On June 14, de Gaulle boarded the French destroyer Combattante at Portsmouth harbor and crossed the English Channel to the Normandy beaches near Courseulles. He set foot on French soil for the first time in four years that day, and by mid-July the U.S. government grudgingly acknowledged the de Gaulle and his national committee had the authority to exercise civil administration in the liberated areas of France.

On August 15, Allied troops landed in southern France during Operation Dragoon and, as the summer wore on, the armored spearheads of the Allied XII and XXI Army Groups, under General Omar Bradley and General Bernard Montgomery, respectively, were steadily progressing toward the frontier of the German Reich.

Ten days after the Dragoon landings, Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division rolled into Paris, liberating the capital city that had already been the scene of fighting between Free French guerrillas and the German garrison. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, had originally intended to bypass Paris, but de Gaulle personally visited Eisenhower and forcefully argued that the French capital should be directly occupied. Not only were the communist elements among the Free French fighting in the city a threat to de Gaulle’s authority, but Paris was also an important communication center and its liberation would be a tremendously symbolic event.

Eisenhower’s hand was forced by de Gaulle and by the unrest in Paris, and General Leonard Gerow, commanding the Allied V Corps, was authorized to release Leclerc to enter the city. However, in short order Gerow expected Leclerc to return to V Corps command and continue its drive across France. De Gaulle informed Gerow that the 2nd Armored Division was to participate in the grand parade the day after the liberation and that French officers would now be taking orders from the French government. Of course, the presence of an armored division parading behind the perceived head of the French government only served to reinforce de Gaulle’s hold on the reins of authority.

By the time Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union issued separate communiqués recognizing the French government as such on October 23, 1944, de Gaulle had already been acting as head of state. His deputies assumed key roles in the government, arrested collaborators, and wrestled with the momentous problems of caring for hundreds of thousands of displaced people, repairing infrastructure devastated by war, jockeying with internal political opposition and with other weighty matters such as the future of the French colonial empire in North Africa, the Middle East, and Indochina.

When Churchill, Roosevelt, and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin met at Yalta in January 1945, France was excluded from the discussions. Again in mid-July, when British Prime Minister Clement Attlee, President Harry Truman, and Stalin met at Potsdam, France was not represented. De Gaulle was not surprised and issued statements that his country would not be bound by any agreements reached without its direct approval. In February 1946, after some debate, France was given an occupation zone in postwar Germany.

By then, however, de Gaulle had already resigned from the country’s presidency, to which he had been formally elected just the previous November. His primary concern was the structure of the postwar government itself. It was to resemble that of the Third Republic with its legislative body rather than the president retaining the majority of the political clout. Such a government, he believed, had been an abject failure as demonstrated by its collapse in the spring of 1940.

“The exclusive regime of the political parties has returned,” he told an assemblage on January 14, 1946. “I condemn it. However, unless I use force to impose a dictatorship, which I do not desire and which would doubtless come to a bad end, I have no means of preventing this experiment. So I must retire.”

The path to power and to the redemption of France had been long and arduous. More than likely, de Gaulle knew that he could not simply fade from the world stage. Although it took longer than he expected, the people called him to serve once again. In December 1958, de Gaulle was elected president of the Fifth Republic, wielding power that closely resembled a model put forth a decade earlier by his failed RPF (Rally of the French People) Party.

De Gaulle’s firm hand and even his mere presence in government quelled the prospects of civil war. He worked toward an acceptable formula for the independence of Algeria, which occurred four years later. He stiff-armed outside influence, refusing to allow American nuclear weapons on French soil and undertaking the country’s own nuclear program, vetoing British entry into the European Common Market due to that country’s close ties with the United States. As far as de Gaulle was concerned, Britain was an American Trojan horse at the gates of the Common Market. On March 7, 1966, de Gaulle took France out of the NATO military alliance, again fearing American hegemony.

In the spring of 1968, de Gaulle’s political curtain call occurred with a forceful radio address that put down a wave of civil unrest related to economic and social issues with words rather than bullets.

On the evening of November 9, 1970, de Gaulle sat down to a game of solitaire, a fitting pursuit for someone who had been a reticent loner for much of his life, and in moments he was unconscious. In less

than an hour he was dead of an aortic aneurysm, 13 days short of his 80th birthday. In keeping with his wishes, written down nearly two decades earlier, there was to be no great fanfare, no solemn eulogy, and no grand state funeral. His epitaph was to read “Charles de Gaulle, 1890- … Nothing more.”

In planning his own final farewell, de Gaulle was brilliant. Modern France was itself his monument. There was no other validation needed for the headstrong, fiercely independent individual who loved his country as he loved himself and became the greatest Frenchman of the 20th century.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments