By John Brown

At the beginning of the battle for Imphal and Kohima, a Japanese Order of the Day instructed the troops: “You will fight to the death. When you are killed, you will fight on with your spirit.”

Toward the end of 1943, with the war turning against Japan in the air, at sea, and on the islands of the Pacific, the planners at Imperial GHQ in Tokyo looked for something that would give Japan a spectacular victory. They found it in a plan submitted by Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi, “the victor of Singapore” and commander of the 15th Army in Burma. It was a plan for an assault on the British in northeast India.

Having recovered from their 900-mile retreat from Rangoon to the northeast border of India in the first half of 1942, the British were building up their forces west of the Chindwin River in the Indian state of Manipur for a counter-offensive to regain Burma. In preparation, thousands of Indian laborers had been sent to the 600-square-mile Plain of Imphal, from which the offensive would be launched, to build roads, airfields, hospitals, and workshops. Huge amounts of weapons, munitions, and transport foodstuffs and all manner of supplies were being stockpiled.

General Mutaguchi, aware of what was going on, planned to forestall a British counter-offensive with an offensive of his own. He would launch his 15th Army across the Chindwin to seize all the transport, weapons, and supplies he needed from the British. This accomplished, he would then advance farther into India where, with the help of a division of the Indian National Army (INA), he would ignite a popular uprising against the British raj. Imperial GHQ approved the plan and gave it the code name U-Go. In addition, GHQ approved a diversionary attack on the British in the coastal Arakan region to the south of Imphal. Code-named Ha-Go, this attack would take place before U-Go and draw British reserves into the Arakan and away from Mutaguchi’s crossing of the Chindwin.

West of the Chindwin, the commander of the British 14th Army, Lt. Gen. William “Bill” Slim, was aware that a Japanese offensive was in the wind. He knew from intercepted signals that the Japanese Burma Area Army was short of supplies, and references to the stockpiles on the Plain of Imphal implied that, in any attack, the objective would be his administrative installations and materiel. Owing to information gleaned from agents in Burma, aerial surveillance, and patrols, he was able to predict most of the moves of a Japanese offensive. Slim therefore decided against a counteroffensive into Burma, choosing instead to await the Japanese offensive and fight a decisive battle on the Plain of Imphal. There he would have his supplies readily available, plus room to use his superiority in armor and aircraft. The Japanese, on the other hand, being at the end of a long and insecure line of supply, would have no such advantage.

In the Arakan, Ha-Go came as a surprise to the two British divisions on that front, the 5th and 7th Indian Divisions. Early in the morning on February 4, 1944, Lt. Gen. Tadashi Hanaya’s 55th Division, spearheaded by 6,000 elite troops of the division’s Infantry Group, attacked the 7th Indian Division near the eastern end of the Ngakyedauk Pass. Hanaya’s plan was to encircle the 7th, isolate it from the 5th and annihilate it, then proceed to annihilate the 5th. His first objective, however, was the capture of the “Admin Box” and its vital supplies and ammunition, located five miles north of the Ngakyedauk Pass at Sinzweya.

The “Admin Box”

The Admin Box was a half square mile of dry rice fields with a central hillock about 150 feet high, surrounded by wire and mines, with bush, jungle, and hills beyond. On the morning of the attack, the only combat troops in the Box were the 2nd Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment (most brigades in Indian Divisions included a battalion of British troops), a battalion of Gurkhas, and two tank squadrons of the 25th Dragoons. There were also six batteries of guns of various calibers. The majority of the 8,000 men in the Box were Indian laborers, administrative personnel, and others called “odds and sods” guarding the supplies.

The attack on the Box began with an unexpected bombardment from guns in the surrounding jungle and hills. Immediately following the bombardment, Japanese infantry launched a fanatical charge. Barbed wire entanglements and mines slowed the assault, while the “odds and sods” snatched up any weapons they could lay their hands on and joined the West Yorkshires and Gurkhas at the perimeter. The artillery, too, was quickly brought into action, firing over open sights. The attack was finally halted and the Japanese fell back into the jungle. This tactic of bombardment followed by frontal attack continued for the next 14 days and nights. Some of the attacks broke into the Box, resulting in hand-to-hand fighting. On one occasion hundreds of screaming Japanese soldiers penetrated the Box and fought their way into the hospital where they slaughtered the sick and wounded. They used the hospital staff and walking wounded as human shields, then shot them and continued fighting. Doctors were forced to attend to Japanese wounded and were then shot. Eventually all the Japanese who infiltrated the Box were killed, many by bayonets and the Gurkhas’ kukris (small boomerang-shaped knives sharpened on the inside edge and used with devastating effect by the tough Nepalese soldiers).

No part of the Box was safe from direct or indirect fire. The wounded, lying on stretchers or waiting for attention, were often wounded again. During the night of February 9/10 a Japanese shell detonated the main ammunition dump. It went up in spectacular fashion, the light so intense it revealed the positions of many Japanese guns. These were quickly targeted and put out of action by counterfire. On February 18 the Japanese began to fade away as British reinforcements, the 26th and 36th Divisions, began moving in.

Ha-Go Fatally Behind Schedule

By now Ha-Go had fallen fatally behind schedule. General Hanaya, instead of continuing his attacks on the Admin Box, should have bypassed it and tried to capture supplies elsewhere. As it was, 5,000 of his troops lay dead in and around the Box with an unknown number in the surrounding jungle and hills. The aim of the diversion had been achieved—it drew six British reserve divisions into the Arakan. These reserves had come from India. General Slim had not been deceived by the feint and had not withdrawn any troops from the Chindwin River front.

Slim was assuming from his intelligence that the Japanese would not cross the Chindwin before mid-March, and so in February he began evacuating thousands of noncombatants—civilians, Indian laborers, and base personnel. Although his predictions of Japanese moves proved largely correct, he did not anticipate that their attack would come as early as it did.

The 200-mile Chindwin River front was covered by the IV Corps of Slim’s 14th Army. The IV Corps comprised three divisions and was commanded by Lt. Gen. George Scoones, whose headquarters was at Imphal. This was a sprawl of houses, bazaars, and gilded temples with the maharajah’s palace in the middle and the bungalows of the British Commissioner and the small European community on the outskirts. Most of the actual front was covered only by observation posts and patrols with two of the divisions deployed around the only two roads leading from the Chindwin to the Plain of Imphal.

The 17th Indian Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. “Punch” Cowan, was to the south around Tiddim at the beginning of a 120-mile fair-weather road leading north to Imphal. Another road ran east from Tiddim to Kalewa on the Chindwin. One hundred miles to the northeast of the 17th Indian Division was the 20th Indian Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Douglas Gracey, deployed between Sittaung on the Chindwin and Tamu toward the southern end of the Kabaw Valley, which guarded the only other road from the Chindwin to the Plain of Imphal. The third division of IV Corps, the 23rd Indian Division commanded by Maj. Gen. Ouvry Roberts, was in reserve at Imphal.

Intelligence believed that a Japanese assault across the Chindwin would concentrate on the two roads leading to Imphal. The commanders of both the 17th and 20th Indian Divisions were under orders to fall back to the Imphal plain when the direction and strength of the Japanese offensives were confirmed, thus drawing the Japanese onto the plain with them.

Mutaguchi Tries to Get the Jump on General Slim

At his headquarters at Maymyo, a hill station 200 miles east of the Chindwin, General Mutaguchi ordered U-Go to begin on the night of March 7/8, some 10 days ahead of General Slim’s calculated date for an offensive. That night Maj. Gen. Yanagida’s 33rd Division crossed the 500-yard-wide Chindwin at Kalewa on the southern portion of the front using both crowded rafts pulled along rope lines tied to each bank and catwalks resting on small boats swung out in the current then fastened to trees on the far bank. The whole division crossed the river undetected, then split into three columns.

The first column, led by Maj. Gen. Yamamoto, with most of the 15th Army’s armor and artillery, moved north up the Kabaw Valley until, on March 11, it reached Maw on the flank of the 20th Indian Division. The second column, farther south, headed for Yazagyo and Tongzang, while the third swung south and west over the mountains via Fort White. Half of this column then headed for Tiddim and Tongzang with the objective of joining the second column in blocking any retreat by the 17th Indian Division along the Tiddim-Imphal road. The other half of the third column made for Milestone 100, unobserved in the jungle-covered hills. Their mission was to block the road between the 17th Indian Division and Imphal, hold the road open for other columns that were leaving a containing force to hold the 17th in place, and then move with all speed on Imphal.

North of the 33rd Division’s crossing point, Mutaguchi’s 15th Division, led by Maj. Gen. Yamauchi, crossed the river a few miles north of Thaungdut on the night of March 15/16. The division then split into two columns, one swinging south to join Yamamoto’s first column, which had the armor and artillery. Their mission was to contain Gracey’s 20th Indian Division. The other column was to make its way on paths into the hills heading for Ukhrul with the objective of cutting the Kohima-Imphal road at Kanglatongbi.

Japanese Soldiers Frolic After Taking The British Supply Depot

On the same night the 15th Division crossed the Chindwin, Mutaguchi’s 31st Division, commanded by Lt. Gen. Kotokui Sato, crossed upriver between the villages of Homalin and Tamanthi. It split into three columns to facilitate marching over the almost impossible razorback mountains before heading for Kohima. Beyond Kohima lay the railhead at Dimapur with its huge storage dumps through which flowed all British supplies and reinforcements from India. The country between the Chindwin and Kohima was so difficult that both Generals Slim and Scoones believed any Japanese attack in that direction could not be made with a force of more than brigade strength. Therefore, Dimapur was virtually undefended.

When Scoones heard that the Japanese attack had begun earlier than either he or Slim had expected and was proceeding much faster and in greater strength than anticipated, he immediately ordered his two forward division commanders—Cowan of the 17th Indian Division at Tiddim and Gracey of the 20th Indian around Tamu—to begin their withdrawals to the Plain of Imphal. At the same time he sent two brigades of his reserve 23rd Indian Division down the Imphal-Tiddim road with orders to keep the road open for the 17th.

Cowan, on receiving the order, delayed a day to wait for the return of some of his dispersed units. As darkness fell on March 14, he finally got the 17th on the road for Imphal. There were some 16,000 men, 2,500 vehicles, and 3,500 mules spread along several miles of road that ran through jungles and among hills rife with possible ambush positions. On March 18 the Japanese captured the supply depot at Milestone 109 not far from Tongzang and went on an orgy of drinking the British-issue rum, beer, and other liquor from the canteen stores and gorging themselves on the unfamiliar foodstuffs they found. This lack of discipline enabled the 17th Indian to get over the Manipur River and blow the bridge behind them.

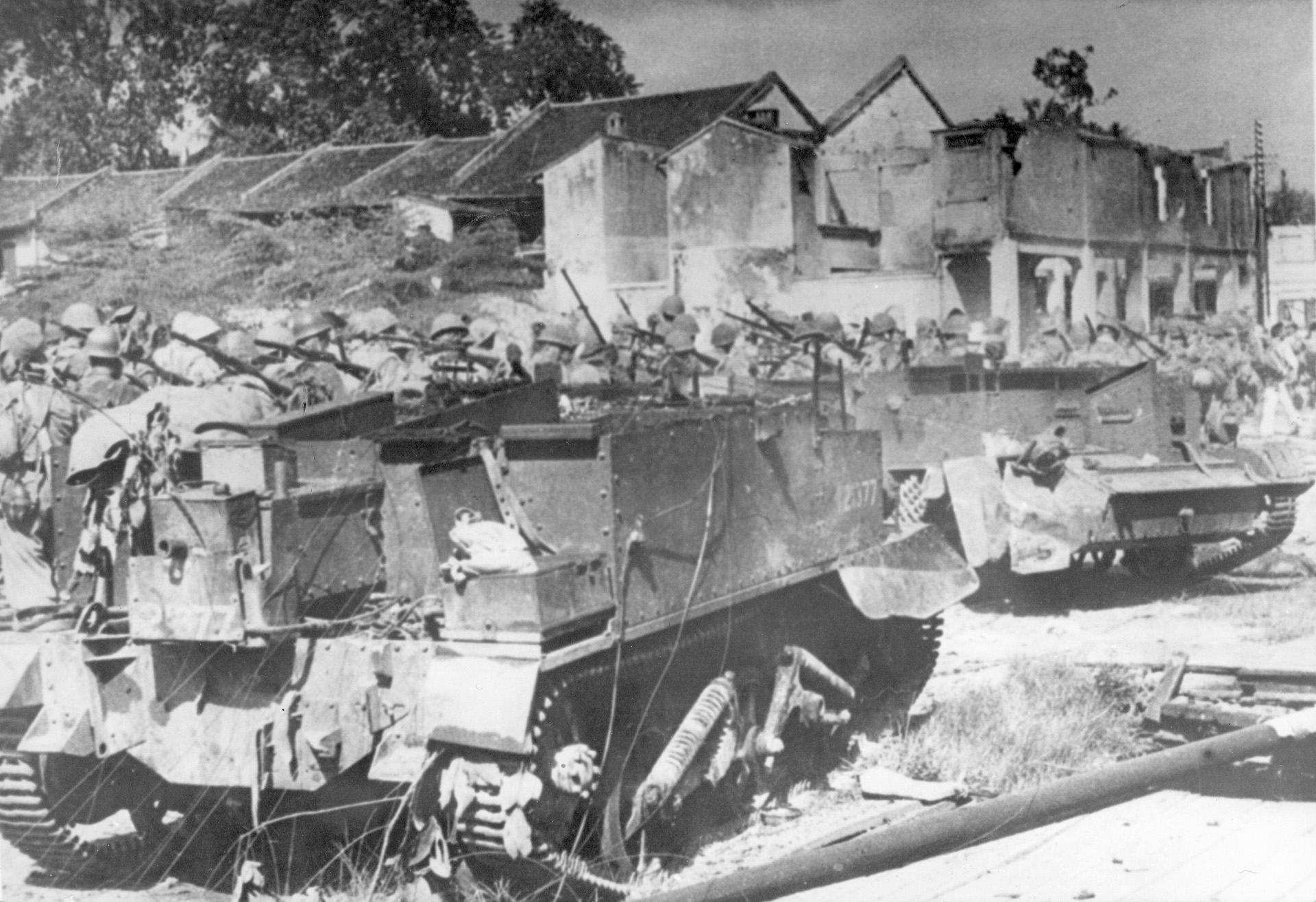

The 17th Indian Division was largely composed of tough, well-trained Gurkhas. Assisted by Sherman and Grant medium tanks, they quickly smashed through three Japanese roadblocks and frustrated several ambush attempts. After a fourth roadblock had been shattered, the Japanese division commander, Yanagida, almost out of supplies and suffering heavy losses, became very depressed. He signaled Mutaguchi, implying that his position was hopeless. Mutaguchi replaced him as commander of the 33rd Division.

The 17th Indian Division’s 120-mile withdrawal to Imphal, during which many actions were fought—some supported by artillery, tanks, and RAF fighters and fighter-bombers—lasted three weeks and cost the division 1,700 casualties. The two brigades of the 23rd Indian Division were sent down the road to assist them and take over the fight with the Japanese.

Spearheading the “March on Delhi”

Northeast of the 17th Indian Division, Gracey got his 20th Indian Division on the move for the Plain of Imphal carrying all supplies possible. In danger of being encircled and cut off by Yamauchi’s 15th Division column descending from the north and Yanagida’s 33rd Division column circling from the south, the 20th Indian Division fought many vicious actions as it fell back toward Palel. At one point a strong detachment of Japanese troops tried to approach a crucial bridge at Sibong that was guarded by Gurkhas. The detachment had with it 40 soldiers, all over six feet tall and powerfully built, each carrying a load of 100 pounds of explosives intended to blow the bridge. The Gurkhas stopped them by setting the scrub alight around and among them with phosphorus mortar bombs. Only one or two of the detachment survived the Gurkhas’ fire to disappear back into the jungle.

Gracey had no intention of allowing the Japanese within gun range of Palel where there was an important airfield on which RAF fighter and supply-drop squadrons were based. If the Japanese took Palel and its nearby supply dumps, they would have a prime starting point from which to overrun the Plain of Imphal. So Gracey fell back slowly, fighting all the way, to Shenam Hill 10 miles southeast of Palel. There the division took up positions on Shenam and the jungle-covered hills around it, which were referred to as “the Saddle.” Running through the hills was a road and tracks that meandered down into the plain. At the Saddle, the 20th Indian Division would make its stand.

Perhaps the most dangerous of the three Japanese thrusts across the Chindwin was the one to the north, General Sato’s 31st Division heading for Kohima and Dimapur. The division was one of the strongest in the Japanese Army with a “bayonet strength” of 20,000. The troops, who were from northern Japan, had the experience of six years of campaigning in China. They were highly motivated and aggressive, the spearhead of the “March on Delhi.”

Harsh Terrain Slows Hope-Thompson’s Advance

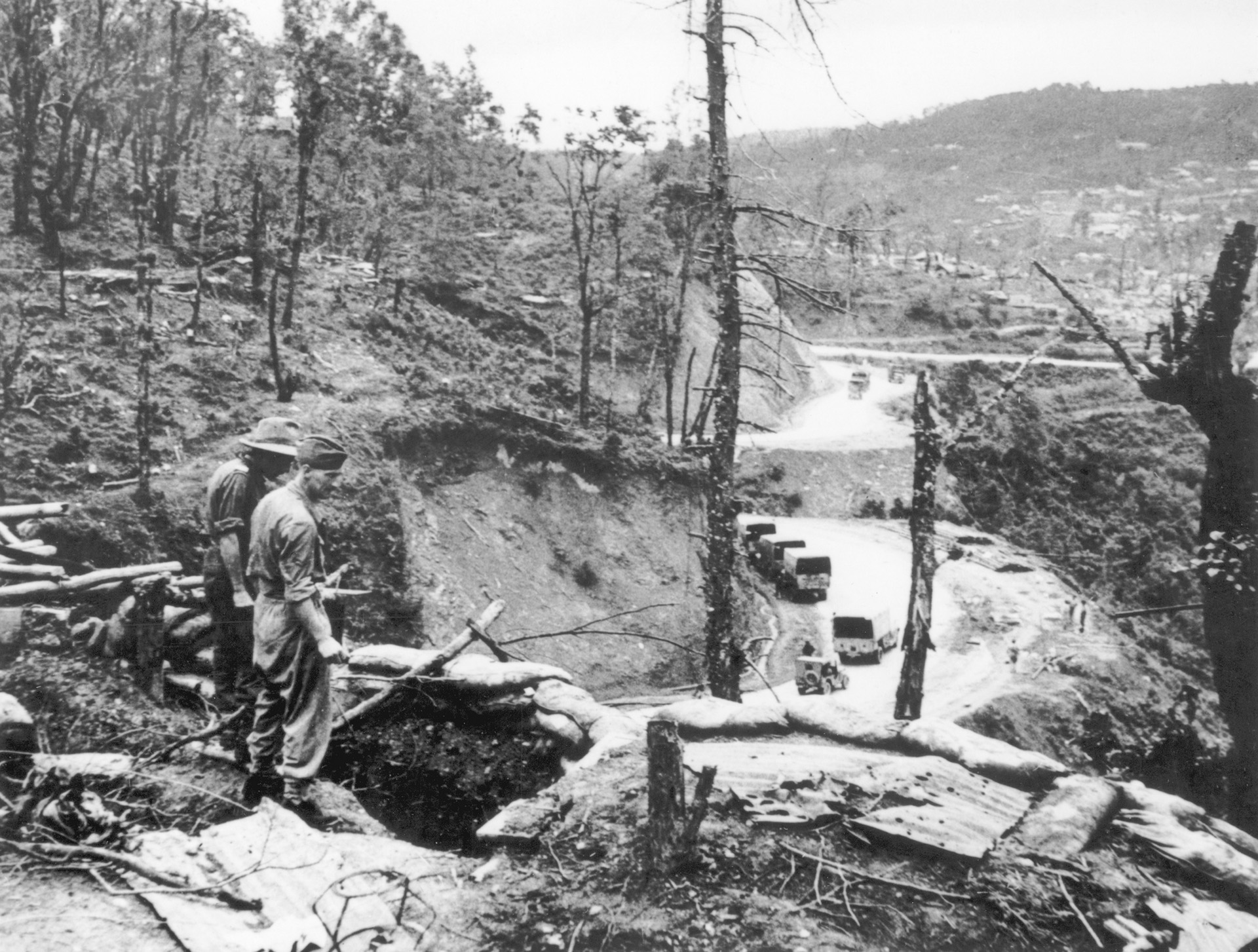

The country they moved across, however, was appalling. On the map the distance from the Chindwin to Kohima was 74 miles, but the terrain forced the division to march 200 miles. They brought with them their guns, some dragged by the crews, some slung on pack animals, including hundreds of oxen that would also serve as meat on the hoof for the troops.

At Kohima a collection of troops of various units—Assam Rifles, Burma Regiment, some Gurkhas and Nepalese—had assembled and were digging in. The only other British force in the area was the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade, composed of one British, one Gurkha, and one Indian Battalion. The brigade was commanded by 32-year-old Brigadier “Tim” Hope-Thomson, who had taken charge when it was formed two years earlier. The British battalion was later sent to the Middle East and replaced with an Indian infantry battalion. The widely dispersed brigade was on a training exercise in the Ukhrul area and unaware of the Japanese advance when Hope-Thomson received a warning that a strong Japanese force was only miles away and coming on fast.

Hope-Thompson managed to bring most of the brigade, along with two mountain artillery batteries and a field ambulance, together into a tight perimeter around the hill village of Sangshak. During the withdrawal to Sangshak one of his paratroop companies was surrounded and almost wiped out by overwhelming numbers of Japanese. The remaining paras, in an attempt to break out, made a final charge and Japanese observers saw the last man on his feet, a British officer, shoot himself in order to die with his soldiers.

Hope-Thomson radioed division and corps headquarters for defense stores, particularly barbed wire and mines, but did not receive anything. With no tools to dig trenches in the rocky ground and told to hold the position to the last man to buy time for the defense of Kohima, the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade prepared to withstand an assault as best it could. The Japanese quickly encircled them and for five days and nights the 2,000 soldiers packed inside a 600-by-300-yard perimeter endured bombardment, continual probes, and suicidal charges from four times their number. Inside the perimeter conditions quickly became appalling. The dead—both men and pack animals—putrefied in the sun. Flies swarmed over everything and everyone, and there was little water. The staff of the 80th Indian Field Ambulance worked wonders, often shielding the wounded from further wounds with their own bodies.

Three Out of Five Unable to Walk

By the fifth day, March 26, 18 of the brigade’s 25 British officers were dead and five were wounded. The commanders of both artillery batteries were dead. Five hundred men were still alive, but only 300 were able to walk. At last light of day the brigade was ordered to fight its way out. That night, under cover of fire from artillery and machine guns, all the wounded except those on the verge of death were carried away into the hills and on to Imphal.

The southern column of Sato’s 31st Division had been held up at Sangshak. The middle column made for Jessami, garrisoned by a battalion of the Assam Regiment, and the northern column made straight for Kohima. Once the Japanese intentions became clear, all outlying detachments were ordered to fall back to defend Kohima.

Kohima, a hill station on a ridge at about 5,000 feet, was the administrative center for Nagaland. There were barracks for a detachment of Assam Rifles, a jail, a hospital, and a reinforcement camp for soldiers returning from leave or on discharge from the hospital and awaiting their orders. The District Commissioner’s residence, with its terraced gardens and a tennis court, had a commanding view of the road by which reinforcements and supplies reached Imphal from the railhead at Dimapur. At the north end of the ridge was a large Naga village. As the Japanese approached, the scratch defense force of the Assam Regiment, Assam Rifles, Burma Regiment, Gurkhas, and others were hastily preparing defenses, but there was no headquarters to coordinate them. There were also about 1,500 civilians, including Naga villagers, in and around the small town. (The Nagas proved to be a great help to the troops, as intelligence gatherers and as porters—men and women—carrying ammunition and other supplies up steep slopes to the troops and bringing down the wounded.)

Heading from Dimapur for Kohima to boost the defense was the 161st Indian Infantry Brigade, but it was held up by a roadblock at Zubza. Sato’s troops had already reached far beyond the Dimapur side. On April 5, the British battalion of this brigade, the 4th Royal West Kents, broke through to Kohima before the Japanese cut the road closer to the town and occupied the northern portion. Their commanding officer, Colonel Hugh Richards, took overall command of Kohima’s garrison. Next day a company of the 5/7 rajputs got into Kohima, but the rest of the brigade was unable to break through and took up positions around Jotsoma three miles west. With them were three mountain batteries of 3.7-inch pack howitzers that would play an invaluable part in the battle.

Siege at Jail Hill

When the leading Japanese troops reached Kohima on the morning of April 5, they swept around the Naga village to Jail Hill, and the siege began. The next night, strengthened as more of the division arrived, they fought their way inside the defense perimeter and captured two positions known as DIS (for Detail Issue Section) and FSD (for Field Supply Depot). The next morning the Royal West Kents counterattacked and annihilated the occupiers. More and more Japanese arrived in the following days and attacks on the defenses became almost continuous. It was then that the 3.7-inch howitzers at Jotsoma gave their invaluable help. At an average range of 3,700 yards, they broke up Japanese formations with astonishingly accurate fire.

The fighting continued day and night. Lance Corp. John Harman of the Royal West Kents, with his section pinned down by heavy fire from a machine gun 50 yards away, sprinted forward and wiped out the gun crew with a grenade, then brought the machine gun back to his men. Shortly afterward he charged another machine-gun post and killed the crew with his rifle and bayonet. As he was returning to his men he was mortally wounded by yet another machine gun. Just before he died, he said, “I got the lot; it was worth it.”

The all-British 2nd Division of Lt. Gen. Montague Stopford’s XXXIII Corps arrived at the railhead at Dimapur in early April from southern India and moved down the road to Kohima. Soon they came up against the Japanese roadblock at Zubza. Here 1st Battalion of the Cameron Highlanders attacked and smashed it with the help of guns and tanks that were winched up steep slopes. During the battle some of the Highlanders witnessed one of their sergeant majors and a Japanese officer engaged in one-on-one combat. The sergeant major won and returned with the Japanese officer’s sword as a trophy.

Imphal Under Heavy Attack

Passing through Jotsoma, the 6th Brigade of the 2nd Division drove into Kohima. The 1st Battalion, Royal Berkshires then made contact with the Royal West Kents, relieving their positions. One of the newly arrived described the scene: “The dead lay unburied. Little squads of grimy and bearded riflemen stared blankly at the relieving troops, many too dazed to realize they were saved and too tired to believe their sleep-starved eyes.” For two weeks the Royal West Kents had fought off regiment after regiment of almost a full Japanese division that had launched 25 full-scale infantry attacks supported by artillery and mortars. Thirteen of the battalion’s officers and 201 men were dead, with most of the others wounded. More than 400 of the other defenders of the garrison were also dead, but the battle for Kohima was far from over.

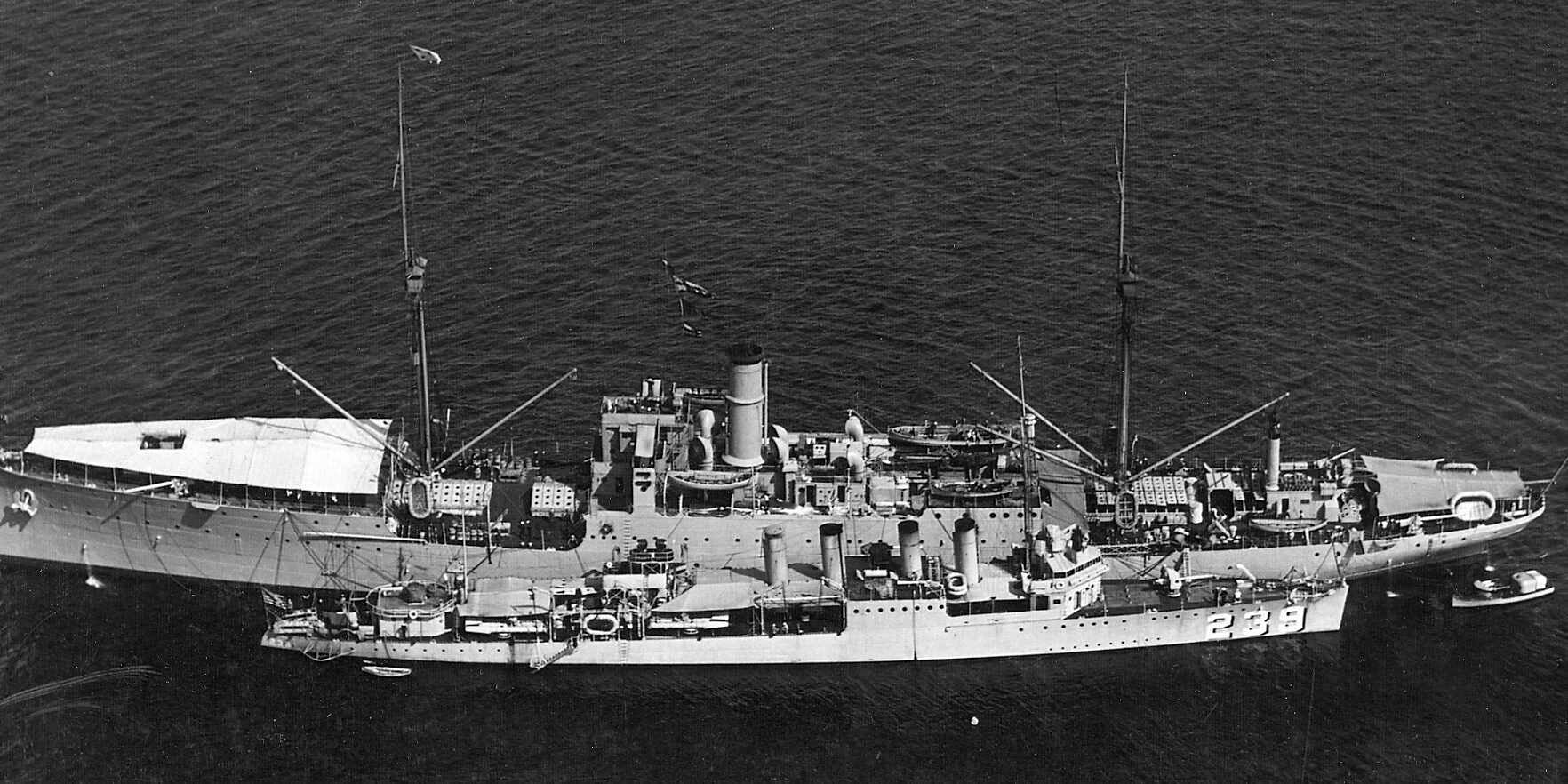

With the road cut between Kohima and Imphal, Imphal was now also under siege. Its only link with the outside world was by air. Imphal lay near the middle of the 30-by-20-mile Plain of Imphal and was surrounded by high jungle-covered hills, their peaks providing excellent views of the plain below. From some of the summits it was only five miles to General Scoones’ headquarters and about the same to the main all-weather airfield on the plain. From these peaks Japanese observers could direct artillery fire on both Imphal and the airfield. Two brigades of the 5th Indian Division now held the northern sector of the plain; in early April the RAF and USAAF had airlifted the division in from the Arakan to join IV Corps. The third brigade of 5th Indian Division had gone to the aid of Kohima.

Northeast of Imphal the Japanese seized the commanding heights of Nungshigum, the highest peak of which stands 1,500 feet above the plain, and dug in. Several attacks were made up the only approach, a steep razorback leading to the ridge of the summit, but they all failed.

Early on the morning of April 13 artillery bombarded the Japanese positions and dive-bombers attacked. A battalion of Dogras, supported by Lee-Grant tanks of the Carabiniers (3rd Dragoon Guards), then moved slowly up the ridge on a very narrow front—one tank’s width. As the tanks crawled up the crest they came under increasingly heavy fire. The tank commanders had to stand in the open hatches to guide the drivers and at the same time fight off Japanese carrying explosives who repeatedly threw themselves at the tanks or climbed on the engine decks in attempts to disable them or kill the crews. Well before the tanks approached the summit, all the tank commanders were dead. But others took their places and the attack continued.

Gracey 20th Remains Delayed

When all the officers had been killed, Squadron Sgt. Maj. Walter Craddock took command of the tanks. Backed up by Subedar (Captain) Ranbir Singh and his Dogras, they moved on to Nungshigum summit and killed every Japanese on it and its slopes.

Troops of the 5th Indian then turned their attention to the other peaks and to the Mapao Spur, from which the Japanese could look down on the plain. They drove the Japanese off these summits in vicious, exhausting fighting. The Japanese, as always, were well dug in and fought to the death. Casualties on both sides were heavy.

Twenty-five miles to the southeast of Imphal, Gracey’s 20th Indian Division was fighting its isolated battle on and around the Shenam Saddle. The battle raged over some 12 square miles of broken, hilly country crisscrossed by deep ravines and watercourses. The division held the road and tracks that led to the plain and kept the Japanese out of gun range of the airfield and stores at Palel.

Early in April Maj. Gen. Yamamoto’s Infantry Group of the 33rd Division, well supported by artillery, had made a determined attempt to smash through to Palel and for a week the battle was in the balance. But the 20th Indian yielded only a mile or so to another series of hilltops, and the battle swayed one way and another. Yamamoto hurled his battalions against British positions and hills were captured and recaptured, with shelling, bombing, and fires stripping the vegetation-covered hills bare. Higher peaks and ridges were held as observation points while fighting—large actions and small—continued on the slopes, in the ravines, and on the road and tracks between battalions, companies, and platoons.

The Japanese Look to the Bridge Along the Silchar Track…

In this sector the Japanese had with them the Gandhi Brigade of the Indian National Army, the “Jifs” (Japanese-Indian Forces), as they were called. On the night of May 2/3, a Jif battalion, which had been under observation, launched an attack that ran straight into an ambush set up by Indian and Gurkha troops. The Jifs suffered heavy casualties. Few prisoners were taken despite General Slim’s order that Jifs should be treated more humanely—previously they had been shot as traitors.

In the middle of May, IV Corps commander Scoones decided that the 20th Indian, having been fighting nonstop for more than six weeks and suffering heavy casualties, could do with “a change of air.” He sent in the 23rd Indian Division to relieve it. Two brigades of the 20th moved north to the Ukhrul road to take on the 15th Japanese Division while the third brigade went west to Bishenpur on the Tiddim-Imphal road. The relatively fresh 23rd Indian Division went straight into the attack, but it was well into June before Japanese pressure eased.

On the western side of the plain the two columns of General Yanagida’s 33rd Division had pushed up the road from Tiddim toward Imphal. On the night of April 14/15 near Potsangbam just south of Bishenpur, one column peeled off and swung west, heading for the 300-foot-long suspension bridge over a deep gorge on the Silchar track, while the other column made a determined drive to take Bishenpur, where the Silchar track joined the road to Imphal. The Silchar track, which had a few months before been upgraded from a footpath to a jeep road, was—with the rail link at Dimapur—one of only two overland links with India. The Japanese were determined to cut it by destroying the suspension bridge. Three Japanese soldiers managed to reach the bridge and blow it up, killing themselves in the process.

Having recuperated after their long fighting withdrawal from Tiddim, the 17th Indian Division now came back to Bishenpur to take on the Japanese 33rd Division again. The foes met at the villages of Ningthoukhong and Potsangbam in a battle that quickly became a swirl of small local attacks and hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets and kukris. Casualties on both sides were heavy, particularly among British officers of Indian and Gurkha units (as they were in all actions) because these men were easily identified by the Japanese at close quarters.

Disease Hits Battalions on Both Sides

To the north, at Kohima, two companies of the 2nd Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry joined the 1st Royal Berkshires on the slopes of Summerhouse Hill. Well dug in, they fended off Japanese attacks in what they described as a charnel house with hundreds of dead British, Indian, Gurkha, and Japanese lying around in advanced stages of decomposition. Dozens of bloated mule carcasses added to the horror. The British position on the hill was separated from a saddleback ridge by a gorge planted with panji stakes (very sharp bamboo stakes planted points up in the ground) and swept by enemy fire. It was also overlooked by a peak 100 yards away known as Kuki Picquet from which Japanese snipers operated.

On April 22, the 1st Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers joined the Berkshires and Durhams on Summerhouse Hill. They attacked Kuki Picquet, but were driven back with heavy losses. Early the next morning the Japanese attacked following a bombardment from artillery and grenade launchers. Advancing shoulder to shoulder, the first waves wore gas masks and threw phosphorus grenades. As they were shot down they were replaced by other waves throwing fragmentation grenades. The Japanese broke through the British line, but the British fell back, reformed around a company headquarters, and repulsed the attack. At 4 am the British counterattacked, clearing the Japanese off the hill.

As more battalions of the British 2nd Division reached Kohima and more of Sato’s 31st Division deployed around it, room for operating shrank. Both sides tried encircling moves in the very difficult terrain around the small township. The terrain was so difficult that the rate of movement unopposed was accepted as one mile per day, and the fighting dissolved into numerous little murderous battles. When the monsoon broke on April 27, movement became more difficult, but the fighting continued despite widespread suffering from diarrhea, dysentery, and beriberi.

Meanwhile, fighting continued day and night on the central Kohima ridge and on other ridges and peaks. On Garrison Hill the Durham Light Infantry fought off one night attack that caused such heavy losses to the Japanese that General Sato ordered a halt to any further night attacks.

At the end of April a battalion of the Dorset Regiment began fighting its way up to the District Commissioner’s bungalow. The Japanese were strongly dug in at the bungalow, on surrounding terraces, and under a huge water tank. The Dorsets reached the edge of a tennis court where only 25 yards separated them from the Japanese.

The “Battle of the Tennis Court” Begins

To move anywhere in the vicinity in daylight meant instant death, so the fighting was conducted at night. For two weeks British soldiers of the Dorset Regiment in black gym shoes or bare feet fought in the dark using grenades and small arms, bayonets, kukris, and machetes in what became known as the “Battle of the Tennis Court.” Then in the middle of May, a single British tank was winched up the spur at the back of the bungalow and began blasting the Japanese bunkers and defenses. More tanks and soldiers arrived and they began a fight for the ridge against the almost unbelievable bravery and ferocity of the Japanese, who always fought to the death.

Kohima Ridge was finally cleared by a combination of troops, tanks, artillery, and air strikes, but fighting continued until the beginning of June when the tattered remnants of the once powerful 31st Division began to fall back northeast along jungle tracks toward Ukhrul. Of the “20,000 bayonets” that had crossed the Chindwin three months earlier, only two or three thousand would survive to recross the river. Thus the division’s casualties were running to 90 percent. The mistake their commander General Sato had made was in laying siege to Kohima. Once he realized that he was facing a determined garrison he should have left a holding force and driven on for Dimapur. He could have easily taken it at the time, which would have been a catastrophe for the British.

To the southeast, on the road to Tiddim, the 23rd Indian Division mounted attack after attack on the Japanese 15th Division in appalling monsoon weather until well into June. The Japanese suffered cruelly and finally began retreating toward the Chindwin. One of their last acts was a raid by a small detachment that penetrated the defenses of Palel airfield and blew up a number of parked aircraft. It was a daring action, one that brought grudging admiration from their opponents, but it was a final gesture. The retreat was under way, with the Indian Division in pursuit, killing as many Japanese as they could.

The Japanese Retreat Into Chindwin

On June 22, tanks of XXXIII Corps coming down from Kohima linked up with elements of the 5th Indian Division, lifting the siege of Imphal.

To the south, around Bishenpur and the Silchar track, some of the most vicious fighting of the campaign had taken place as the Japanese 33rd Division tried to break through to Imphal. The 33rd Division’s losses were enormous, but its soldiers kept attacking until the monsoon completely halted their resupply. Mutaguchi then ordered the division to give up its attempt to break through and withdraw.

The remnants of the Japanese 15th and 31st Divisions regrouped in and around Ukhrul for a last offensive, but during the first days of July the 23rd Indian Division hit them hard and badly mauled them. The survivors began a retreat to the Chindwin, pursued by the 23rd as far as Tamu at the head of the Kabaw Valley. Here the newly arrived 11th East African Division took over the pursuit down the valley.

The retreat to the Chindwin was a nightmare for the Japanese troops, and little better for the British forces involved. Mists on the hillsides hindered or prevented air supply and the monsoon rains had washed out roads and turned tracks into mudslides. Rations often couldn’t get through to the troops and they went hungry. Tropical diseases of all kinds were rampant, adding to the misery of the wounded. Stretcher-bearers carried them for days over awful terrain, each bearer carrying a spade to bury those who died on the journey. Elephants were used where possible to carry wounded, but at best they could move only three miles in 16 hours. As the retreat moved on at a snail’s pace the pursuers saw more and more bodies of Japanese soldiers who had died of disease, starvation, or wounds. Still, many stood and fought, waiting in ambush with a grenade or a bullet to take one of their enemies with them when they died.

Some 85,000 to 90,000 Japanese had crossed the Chindwin River in March. Their casualties in the four-month battle were around 60,000, with perhaps another 20,000 dying during their retreat. Metaguchi’s 15th Army was virtually destroyed. Indian-Gurkha-British losses were less than 20,000, low compared to those of the Japanese because of first-class medical services and air evacuation to hospitals.

Air power had a great deal to do with the victory. The RAF and USAAF flew thousands of sorties in close support of the troops, brought in reinforcements, dropped supplies, and evacuated the sick and wounded. Tanks and artillery were also important factors. But the rockbed of success lay in the indomitable spirit and fighting qualities of the Indian and Gurkha battalions and their British officers and of their British regimental comrades. They fought and outlasted a formidable foe whose courage and endurance they would long remember and respect.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments