By Mark Simmons

The legend of 1940, “their finest hour,” has become almost considered fact in Britain. Many felt, as they saw it at the time, the Germans merely had to turn up on her shores for Britain’s defeat. Indeed, strong opinion in the United States, too, felt it was only a matter of time before Britain and her empire would fall to the jackbooted Nazis.

It was often said at the time, and afterward in memoires, that “Britain had nothing.” But average citizens knew little about the real situation, only what they saw: the antics of the Civil Defence volunteers, later to become the Home Guard, “Dad’s Army” parading with broom handles. Or the newsreels depicting a defeated army plucked from the beaches of Dunkirk by the little ships. And later they witnessed the vapor trails in the skies above southern England as the RAF fighter pilots—“the few”—took on the mighty Luftwaffe, the world’s most powerful air force.

Yet, on the other side of the hill, the Germans, after their stunning victory against France and much of Western Europe, were as confused in victory as the British were in defeat. For them there were many problems in taking on Britain and her empire. On June 30, 1940, Maj. Gen. Alfred Jodl, Hitler’s closest military adviser, expressed the view that final German victory was inevitable and “only a matter of time.” Yet this was a simplified view. Vice Admiral Kurt Assman of the naval staff was nearer reality when he sarcastically dismissed this view with, “We Germans could not simply swim over.”

On May 21, when Hitler met with Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander of the Kriegsmarine, a proposed invasion of Britain was first raised and briefly discussed. The admiral asked beforehand how the war was going. All Hitler would tell him was “the big battle was in full swing.” Operation Yellow, the attack on France and the Low Countries, was not expected to bring about a rapid collapse of the Allies.

Hitler showed no interest in the invasion project and, at their next meeting on June 4, by which date the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had been evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk, the subject was not even mentioned.

Even after the defeat of France, Hitler did not exploit the advantage and attack Britain. Luftwaffe aircraft were ordered not to infiltrate British airspace. The mood in Berlin as well as in the Army was that the war was virtually over. Most felt the British could be induced to make peace. When the “crazy English” rejected Hitler’s peace offer speech in the Reichstag on July 19, the practical problems of an invasion began to loom.

On July 16, 1940, Hitler issued his directive No. 16, which began: “As England, in spite of the hopelessness of her military position, has so far shown herself unwilling to come to any compromise, I have decided to begin to prepare for, and if necessary to carry out, an invasion of England.”

It was nearly six weeks since the “Miracle of Dunkirk,” when 338,226 Allied troops were evacuated to Britain, although losing all their heavy equipment, in Operation Dynamo. Some indeed were brought to Britain in small boats and ships, but the vast majority were brought off in destroyers and transports, carried out under fairly continuous air attack.

There were then no plans in the German High Command of the Armed Forces (OKW) for an invasion of Britain. The Kriegsmarine had produced a study in November 1939 of the problems that such an operation might pose. It identified two preconditions—air and naval superiority—of which the Germans, in 1940, had neither.

The Kriegsmarine was poorly equipped for such an undertaking. It had no purpose-built landing craft worth mentioning. It had suffered heavily in the Norway campaign. All it had available was one heavy cruiser, the Hipper, three light cruisers, and nine destroyers. All other major warships had been damaged or were not yet commissioned.

Besides, the British fleet was overwhelmingly powerful. The Germans might be able to flank the invasion sea lanes with mines, but sea minefields were notoriously hard to maintain and the Royal Navy would certainly target this operation.

Everything, then, depended on the Luftwaffe being able to deal with the Royal Navy and RAF—and still support their landing forces. But could the Luftwaffe, with all its bluster, led by its commander Hermann Göring, who did not even attend any preinvasion meetings but who boasted it could knock Britain out single-handed, defeat the Royal Navy? Certainly the German naval commanders were not confident in the Luftwaffe’s ability to perform all these tasks.

At this stage the invasion was codenamed Operation Lion but was soon changed to Sea Lion (Seelöwe).

For their part, the Wehrmacht commanders wanted to land on a broad front stretching from Ramsgate near Dover to west of Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight. The first wave would consist of some 90,000 men landing in three main areas; by the third day the Germans expected to have 260,000 men ashore.

The Kriegsmarine planners had grave misgivings, though, favoring postponement until the spring of 1941, arguing that the Navy was still far too weak. They also pointed to the fact that the weather in the English Channel was unpredictable and presented great hazards for their motley invasion fleet, none of which was purpose-built for the task. The Army wanted to land at dawn; the tides on August 20-26 or September 19-26, 1940, would be suitable. The Navy, seemingly losing the argument on postponement, could not be ready for August, so September was chosen. Even in the best of conditions, the river barges that made up most of the invasion fleet would be slower crossing the Channel than Caesar’s legions 2,000 years earlier.

The Kriegsmarine expected to lose 10 percent of its lift capacity due to accidents and breakdowns before the Royal Navy and RAF took action. Raeder used these arguments to insist on a narrow-front invasion from Dover to Eastbourne, adding that the Luftwaffe would be unable to protect the long front.

Colonel General Franz Halder wrote in his diary that the Army rejected the Navy’s plea for a short front. “From the Army’s point of view,” he said, “I regard it as complete suicide.” However, Hitler would back the Navy view.

At the beginning of August, Hitler directed the Luftwaffe to “strike down” the RAF. For the coming battle the Germans had some 2,500 serviceable aircraft: 1,000 medium bombers (He-III, Do-17, and Ju-88); about 260 Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers; and approximately 1,000 fighters—800 Me-109s and 220 twin-engine Me-110s. These were divided into three air fleets, or Luftflotte.

Luftflotte 2, based in Holland, Belgium, and northern France, was commanded by the capable Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, a former Army officer who would later command field armies. Luftflotte 3 was to the south and west of France under Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle, who had commanded German air forces during the Spanish Civil War. Luftflotte 5, based in Norway and Denmark and commanded by Colonel General Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, would create a diversion by attacking northern England.

The Luftwaffe had been one of the main keys to German victories in Poland, Norway, and France. However, its main role was supporting the army but not as an independent strategic air force. It lacked long-range heavy bombers and long-range fighters. It was severely limited by the endurance of the main fighter, the Me-109, of about 80 minutes. Having to cross and recross the Channel, it could barely stay in British air space for more than 20 minutes.

The longer range Me-110 proved unable to hold its own against the more maneuverable British fighters. Thus the bombers that needed protection were restricted to the fighters’ range and even then not enough Me 109s were available. As each bomber required an escort of two fighters, only about 400 bombers could be deployed at any one time. However, the Luftwaffe’s commanders were basking in their recent victories and overestimated their own capabilities.

Hermann Göring had no real ability to command a modern air force, being more at home with politics; he spent much of the upcoming battle in his country estate at Karinhall. He had such contempt for the RAF he felt it would be destroyed in four days in the south of England.

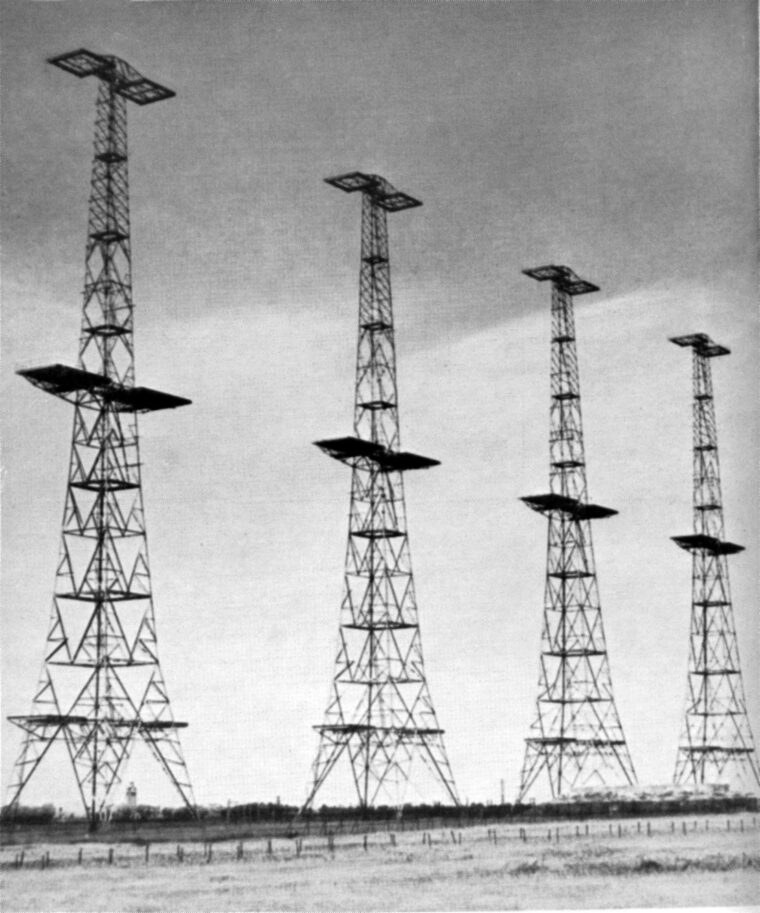

However, the RAF had been preparing for this type of battle for several years, and by 1940 a sophisticated system of air defense was largely in place. At its backbone was a chain of 52 radar stations covering the coast from Pembrokeshire to the Shetlands. Although not complete by 1940, the system was still able to give good information on the bearing, altitude, and numbers of enemy aircraft from about 70 miles out. Thus, the defending fighters could be guided to the targets, relieving them of the need to maintain time-consuming standing patrols. Without radar, the RAF would have been seriously strained, to say the least.

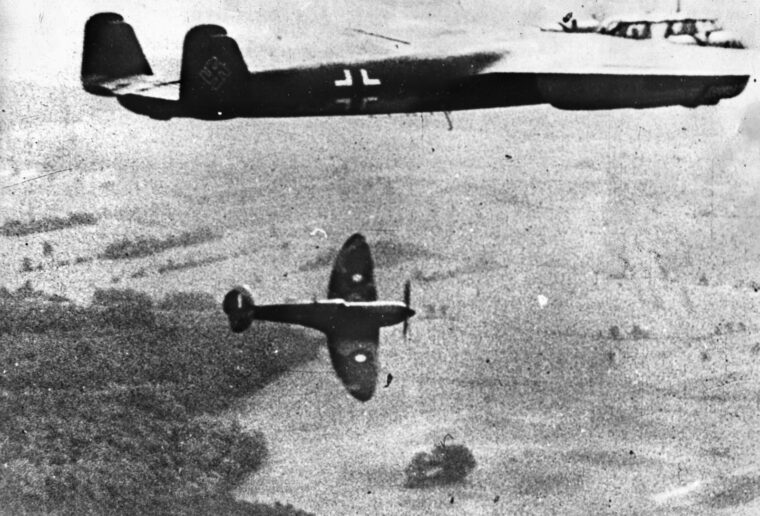

At the end of July 1940, the RAF had about 1,200 aircraft, over half of which were fighters. Most of the 55 fighter squadrons were equipped with Hurricanes or Spitfires, both of which were armed with eight wing-mounted Browning .303-caliber machine guns; a two-second burst could blow an enemy aircraft out of the sky. The Hurricane was the mainstay of Fighter Command. Highly maneuverable, it was nevertheless inferior in performance to the Me-109.

The Spitfire, on the other hand, had a similar performance to the Me-109, although the system of direct fuel injection gave the German machine the edge.

Nevertheless, aircraft production in Britain was outstripping that in Germany, producing twice as many fighters in June-September 1940: 470 Hurricanes and Spitfires to fewer than 200 Me-109s.

Yet it was the pilot situation that would be most critical in the coming battle. Some 300 British fighter pilots had been lost to Fighter Command during the Battle of France, when the BEF tried to hold off the German invaders. At the beginning of the Battle of Britain, then, Fighter Command was 154 pilots below complement.

In the coming battle, the remaining pilots would be fighting over their own territory, so RAF pilots who bailed out or crash landed could be quickly returned to the fight. Also to Fighter Command’s aid came welcome reinforcements from the occupied countries and the Commonwealth and volunteers from the United States (the American Eagle Squadrons).

Another factor was that the RAF’s Fighter Command was led by highly professional men such as Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding. Reserved and dedicated, Dowding was a complete contrast to the bombastic Göring.

Fighter Command was divided into four groups. No. 10 Group covered southwest England and Wales under Air Vice Marshal Sir Quinton Brand. No. 11 Group covered London and the southeast under Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, a New Zealander. No. 12 Group covered the Midlands under Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, and No .13, under Air Vice Marshal R.E. Saul, was responsible for Scotland and the north.

Park’s No. 11 Group, which would bear the brunt of the battle, had seven sector stations at Tanmere, Northolt, North Weald, Debden, Hornchurch, Biggin Hill, and Kenley. The other groups were also divided into sector stations. Fighter Command’s headquarters were at Bentley Priory near Stanmore and had an overall view of the fighting. The tactical conduct of the battle, however, was left to the groups and sectors.

Early in July 1940, the Luftwaffe began trying to wear down Fighter Command by attacking ports and convoys in the Channel. However, Dowding refused to be drawn in, committing only a few squadrons. The Germans sank 30,000 tons of shipping and gained air superiority in daylight over the Dover Straits but lost twice as many aircraft as the British.

Various dates are given for the opening of the Battle of Britain. The official account published in 1941 by His Majesty’s Stationery Office gives August 8, 1940. Dowding accepted August 8 but pointed out that the first attack in force actually took place on July 10 when 70 German aircraft attacked Portland in an attempt “to bring our Fighter Defence to battle on a large scale.”

On August 12, the Luftwaffe struck its first heavy blows at RAF fighter airfields and radar stations when six radar stations were hit; Ventnor on the Isle of Wight was out of action for 10 days. The next day, Adlertag, or Eagle Day, which was to mark the beginning of the main assault, proved an anticlimax. The radar stations were not attacked, although several airfields were heavily bombed. But, often due to faulty German staff work, airfields such as Eastchurch, Detling, and Andover were hit but they were not fighter stations.

On August 15 the Luftwaffe flew its greatest number of sorties during the battle: 1,786. All the German fighters were committed as well as all three Luftflotte. However, 75 German aircraft were shot down, while the RAF lost 34. Luftflotte 5 was severely mauled by Nos 12 and 13 Groups and as a result took no further part in the battle.

The following day the British fighter stations came under attack. Tangmere in No. 11 Group was heavily bombed, but its squadrons were already airborne when Stukas of Stukageschwader 2 hit the base, which left it badly damaged. Station workshops, the sick bay, water pumping station, officer’s mess, and five hangers were destroyed or damaged. Six Blenheim bombers, seven Hurricanes, and two Spitfires were destroyed or damaged on the ground. Thirteen people were killed with another 20 wounded.

During the attack, a badly damaged Hurricane crash landed at Tangmere. The pilot was William “Billy” Fisk of 601 Squadron, the first American to die for the British cause and a very popular pilot at Tangmere, noted for driving a four-liter Bentley in British racing green.

Fisk’s flight commander, Sir Archibald Hope, was quickly on the scene. “There were two ambulance men there,” he said. “They had got Billy Fiske out of the cockpit. They didn’t know how to take off his parachute so I showed them. Billy was burnt about the hands and ankles. I told him. ‘Don’t worry. You’ll be all right…’ Our adjutant went to see him in hospital at Chichester that night. Billy was sitting up in bed, perky as hell. The next thing we heard he was dead. Died of shock.” (See WWII Quarterly, Summer 2010.)

Another wave of heavy attacks on August 18 was followed by a spell of cloudy weather that brought the first phase to an end. By now Göring believed Dowding was down to 300 fighters when, in fact, the British had more than twice that figure. The Luftwaffe tactic was to keep hitting the fighter stations, which they hoped would draw the British into an all-out fighter action. However, on Park’s orders British fighter pilots were to engage the bombers and try to avoid tangling with the Me-109s.

This forced the Germans to deploy more of their fighters in close bomber support rather than in more productive offensive sweeps. To reinforce the escorts for the bombers, most of the Me-109s in Sperrle’s area were transferred to Kesselring; the Ju-87s, which had suffered heavy losses, were withdrawn.

On August 24 the second phase of the battle began with Luftfotte 2 attacking No. 11 Group’s airfield at Manston; it was badly damaged and evacuated.

Over the next 10 days the Luftwaffe began to narrow the gap in aircraft losses and came close to winning air superiority over Kent and Sussex. This was due partly to a change in tactics; they maintained continuous air patrols over the Straits of Dover and launched frequent feint attacks that confused the directors of Fighter Command.

When they came up to do battle, Park’s pilots found the bombers protected by swarms of Me-109s. Losses narrowed over a week from the last day of August to September 6, when the Luftwaffe lost 225 aircraft and the British 185 fighters. As bombers accounted for more than half the German aircraft, the British were losing considerably more fighters.

The Luftwaffe was also causing crippling damage to No. 11 Group’s airfield facilities. Biggin Hill was attacked six times in three days; all buildings were damaged and 70 ground staff were wounded or killed.

Park felt that during the period August 28-September 5 he was seriously hampered in deploying his squadrons. This was “felt for about a week in the handling of squadrons by day to meet the enemy’s massed attacks.” Continued pressure would force Park to withdraw his squadrons north of the Thames, from which a defense of southeast England would be difficult.

However, on September 7, Göring switched the main attacks from the fighters’ stations to London, thereby relaxing the pressure on Fighter Command’s No. 11 Group airfields. Late in the afternoon, 300 German bombers, escorted by 600 fighters, attacked the capital; the East End and London Docks took the brunt of the attack and were soon blazing. Fighter Command was taken by surprise, and the Luftwaffe suffered few losses. That night the blazing oil refineries and warehouses acted as a beacon for 250 more bombers that added to the inferno.

Why did the Germans change their tactics? Often put forward as the main reason for the switch to attacking London was a reprisal for British raids on Berlin, which had been ordered as reprisals for the accidental bombing of London on the night of August 24, 1940.

There was rather more to it than that, however. The day of decision for Sea Lion was close, and preparations for the invasion were not going well. The Luftwaffe had its hands full trying to overcome Fighter Command and had been unable to divert attacks against warships or coastal defenses.

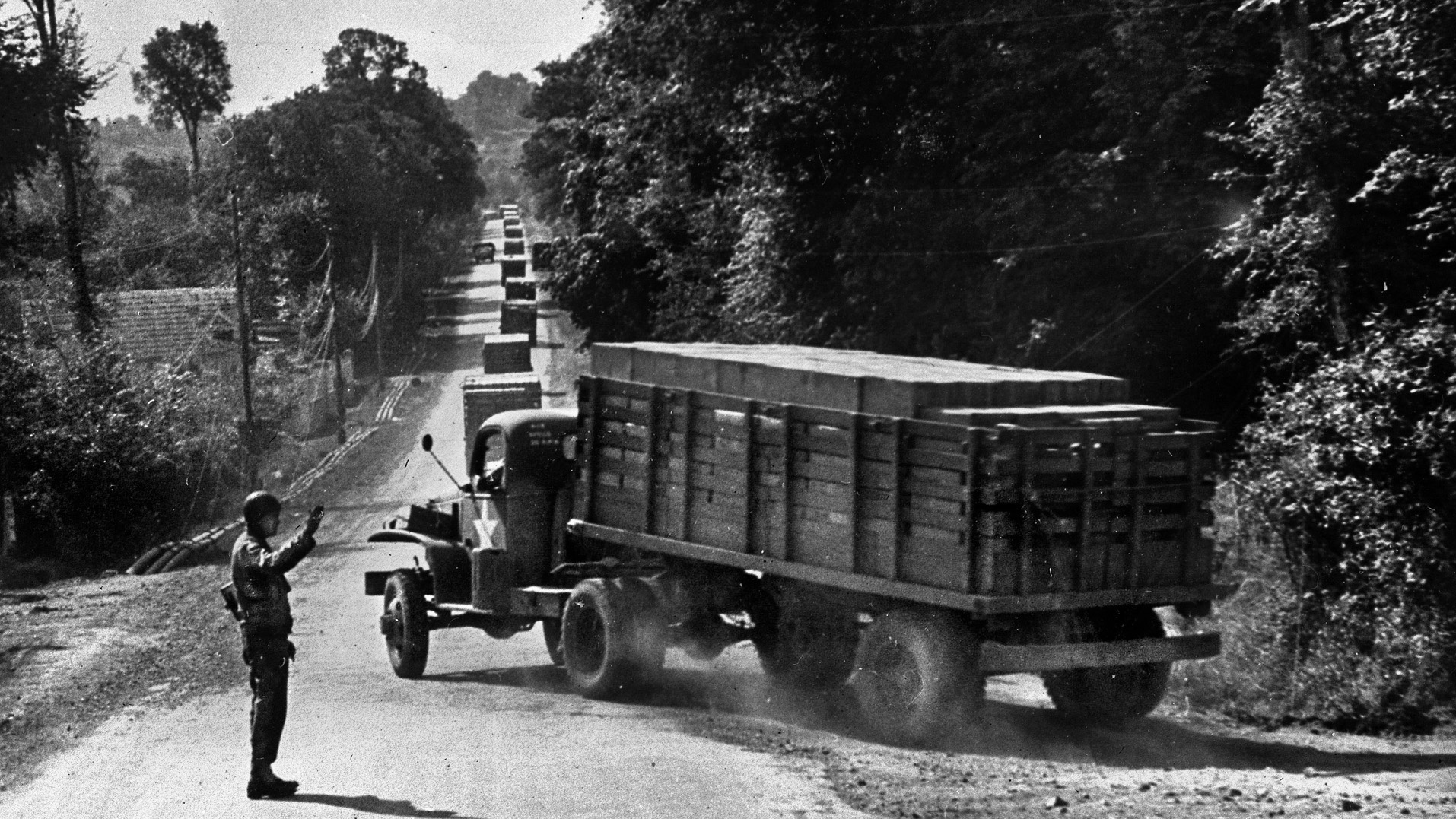

Meanwhile, RAF Bomber Command, under Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, was bombing invasion barges moored in Ostend in occupied Holland and going so far as to claim it was these attacks “that convinced the Germans of the futility of attempting to cross the Channel.” However, the Royal Navy had bombarded minesweepers and barges, hitting Dunkirk, Boulogne, Calais, Ostend, and Cherbourg.

In addition, Admiral Reginald Drax’s naval flotillas from the Nore at the mouth of the Thames raided several of the Germans’ invasion ports (Dunkirk, Boulogne, Calais, and Ostend) and sank several invasion barges, while flotillas from Plymouth and Portsmouth organized similar raids on ports of embarkation. British naval intelligence claimed 12.5 percent of transports and 12.6 percent of barges had been lost to British attacks.

The German Army was also getting cold feet when it realized the essential panzer divisions would have to be loaded in the Antwerp area—a long way from the landing areas—and they would be extremely vulnerable on the long “flank march” with little naval protection. Minefields were regarded with skepticism, and the Germans did not have enough mines, anyway.

The Royal Navy was carrying out regular sweeps with destroyers and motor torpedo boats and, on the night of September 8/9, these were joined by the 2nd Cruiser Squadron. These sweeps curtailed German coastal movements of shipping by night. This alone had a great deterrent effect, for the Germans had no way to challenge it. Hitler was expected to give the order for S-Day on September 11, but he postponed his decision until September 14, bearing in mind that 10 days were needed to implement the decision.

London was attacked again by large forces on September 9, 11, and 14, and heavily bombed every night. On September 11 the Luftwaffe inflicted greater losses than it incurred, while on the 14th it was nearly a draw. Also on the 14th, Hitler declared that Sea Lion was “not yet practical” because the Luftwaffe had not achieved air supremacy. Urged on by a confident Göring that air supremacy was just a couple of days away, Hitler again postponed his decision until September 17.

On September 15, the Luftwaffe launched two large attacks against London. However, the tactics of feints that had served them so well were abandoned, thus Park was able to deploy his fighters to better effect. Leigh-Mallory’s No. 12 Group also joined the battle with five squadrons, led by Squadron Leader Douglas Bader. The Luftwaffe took a heavy beating, losing over 50 aircraft while Fighter Command lost half that number. More significantly, few of the German bombers succeeded in reaching their targets.

It was obvious now that the Luftwaffe was not close to destroying Fighter Command nor gaining air supremacy. And the terror bombing of the civilian population seemed unlikely to break the British will to resist. The German naval staff identified the likely abandonment of Sea Lion on September 10.

They argued, “It would be more in the sense of the planned preparation for operation ‘Sea Lion’ if the Luftwaffe would now concentrate less on London and more on Portsmouth and Dover, and on the naval forces in or near the operation…. The Naval War Staff, however, does not consider it suitable to approach the Führer now with such demands, because the Führer looks upon a large-scale attack on London as possibly being decisive … bombardment of London might produce an attitude in the enemy which will make the ‘Sea Lion’ operation completely unnecessary.”

On September 17, Hitler postponed Sea Lion indefinitely, and with continued attacks being made against the invasion fleet two days later ordered that dispersed. September 15 has come to be celebrated in the United Kingdom as Battle of Britain Day.

There were several reasons for the Luftwaffe’s failure in the Battle of Britain: Göring’s poor leadership; the failure to identify Britain’s radar screen as key to the defence; the shortage of Me-109s and that aircraft’s lack of range; the high morale of Fighter Command’s pilots and ground crews; and the skilful tactics of Dowding and Park (the latter was surely the victor of the Battle of Britain).

However, this did not prevent both Dowding and Park from being sacked shortly after the battle. Their conduct of the battle, in particular their reluctance to use their fighters in “Big Wings” advocated by Leigh-Mallory, made it a close-run thing, for a simplistic comparison of losses showed the battle of attrition did not favor the RAF, even with its advantages.

In the course of the battle, Fighter Command lost 915 aircraft, the Luftwaffe 1,733. By the end of the battle Fighter Command had more aircraft than it did at the beginning; it took the Luftwaffe longer to recover, mainly because of Germany’s low rate of aircraft production.

The conclusion was that the Battle of Britain air campaign was not the principal reason that the invasion was prevented. This perception that the RAF was Britain’s savior came about more as a propaganda tool to inspire the public in Britain and the United States. Indeed, many Germans, including Luftwaffe air ace Adolf Galland, felt that the Battle of Britain was the Battle for Britain—the invasion battle that was never fought.

The invasion of Britain was thwarted by all parts of Britain: politicians (Churchill most of all) who were determined to fight, backed by the public; the British Army that prepared to defend the beaches; the Merchant Navy, and, of course, the RAF. But the principal dissuading factor in the minds of Adolf Hitler and his admirals and generals was the Royal Navy. In particular, the German naval planners never believed that the Luftwaffe could defeat the immense numerical superiority of the Royal Navy, regardless of gaining a degree of air superiority.

The Battle of Britain did have far-reaching strategic consequences despite its inconclusive outcome. It was the first setback suffered by German forces in World War II; Hitler realized that by 1941 Britain would be too tough a nut to crack. Instead, he pursued a costly strategy in the Mediterranean, and in his invasion of the Soviet Union—Operation Barbarossa—planning for which had already started before the Battle of Britain had really begun, whereby he had to leave 35 divisions to face the British for an invasion that was never launched.

A military medal, the 1939-45 Star, with the clasp “Battle of Britain,” was issued to all aircrew of the Royal Air Force from throughout the empire and the Allies who flew operations between July 10, 1940 and October 31, 1940.

Unfortunately, “the few” to whom the many in Britain owed so much did not include those members of the Royal Navy, who never received the recognition that was due them.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments