By Tom Yarborough

On a serene Sunday morning the residents of Oahu enjoyed the dawning of another gorgeous day in paradise. Unknown to them, three converging formations of military aircraft navigated toward their lush island, homing in on the soothing Hawaiian music playing on Honolulu radio stations KGMB and KGU.

The night before, Lt. Col. Clay Hoppaugh, signal officer for the Hawaiian Air Force, had contacted Welby Edwards, manager of KGMB, and asked that the station remain on all night so a flight of Army Air Corps Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers flying from California could home in on the station’s signal. Actually, it was a less than well-kept secret that whenever the station played music all night, aircraft flew in from the mainland the next morning.

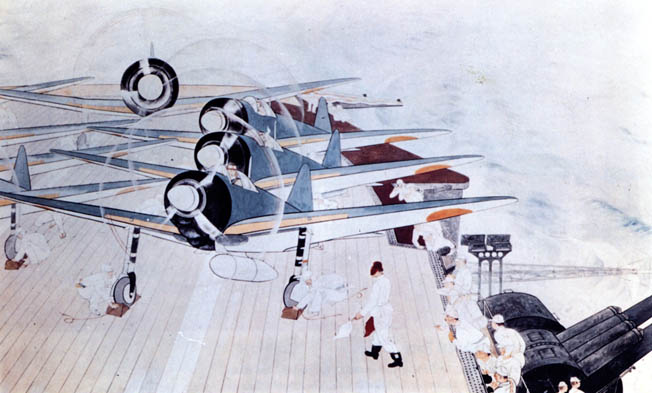

Being nondirectional, however, that same music also drifted into the radio receivers in the operations rooms of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s six Japanese aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku, and Zuikaku, located roughly 300 miles north of Oahu. Nagumo’s task force monitored the station throughout the night for any hint of a military alert on Oahu, and at approximately 7 am on Sunday Lt. Cmdr. Mitsuo Fuchida, leading his formation toward Oahu, also tuned in KGMB to guide his 183 aircraft to their destination. While Fuchida homed in on KGMB’s signal, 18 U.S. Navy Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers took off from the aircraft carrier Enterprise 200 miles west of Oahu and tuned in radio station KGU to get some homing practice of their own. Shortly after 8 am, the three converging formations, each tracking inbound on the same innocent radio beams, collided in brutal and deadly aerial combat that would plunge the United States into World War II. The date was December 7, 1941.

The story of the Japanese surprise attack on Perl Harbor is, of course, much broader and more nuanced than just the events surrounding the devastating strike against the United States Navy’s Pacific Fleet. In the over 70 years since the attack, there has been no shortage of books and articles detailing events on the “Day of Infamy,” yet most accounts focus almost exclusively on what happened to the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor.

Incongruously, scant attention has been paid to the drama of swirling air-to-air combat over Oahu on December 7. For the most part, the aerial battles and dogfights are relegated to footnotes or to a few obscure paragraphs scattered among dozens of sources. Yet the clashes in the air are as compelling, electrifying, and powerful as any actions at Pearl Harbor. Although new sources, American and Japanese, have clarified and in some cases altered the facts about a few iconic episodes, the handful of airmen who fought, and in some cases died, that Sunday morning were truly American heroes who willingly flew to the sound of battle and carried the fight to a determined enemy. Their fight adds a vital missing dimension to the long-established Pearl Harbor story.

“Tora! Tora! Tora!”

The aerial saga began at approximately 6:15 am on December 7, as Commander Minoru Genda, principal planner of the Pearl Harbor attack, watched anxiously aboard the carrier Akagi as his close friend and Eta Jima Naval Academy classmate Mitsuo Fuchida led the first wave of aircraft into the gray dawn. Both men were seasoned carrier pilots and combat veterans from China. Genda had also served a tour in London in 1940 as assistant naval attaché. He had been extremely impressed by the British carrier-based torpedo plane attack that sank or damaged several ships of the Italian Navy’s Mediterranean fleet at the harbor of Taranto, so he felt confident that Fuchida would accomplish a similar feat at Pearl Harbor.

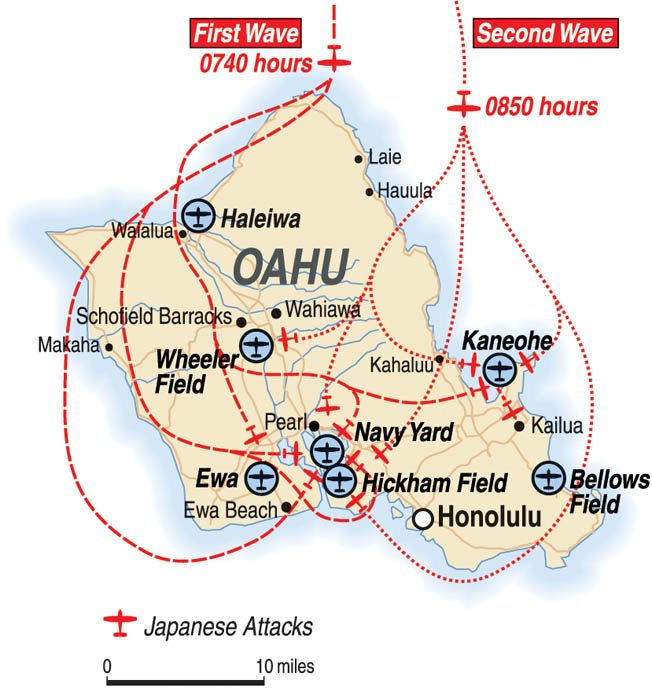

Confidence also permeated the thoughts of the strike commander. As he flew south in his Nakajima B5N2 Kate bomber, a flamboyant Fuchida wore red underwear and a red shirt, reasoning that blood would not show if he were wounded and therefore would not demoralize the other fliers. So it was in that frame of mind as he approached Oahu’s North Shore that Fuchida observed a tranquil, peaceful panorama before him; his first wave had achieved complete surprise. He gave the attack order at 7:40 am, unleashing 43 Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters, 49 high-level Kate bombers, 51 Aichi D3A1 Val dive bombers, and 40 Kate torpedo bombers into battle. Then, at 7:53 he sent his infamous message confirming total strategic and tactical surprise: “Tora! Tora! Tora!”

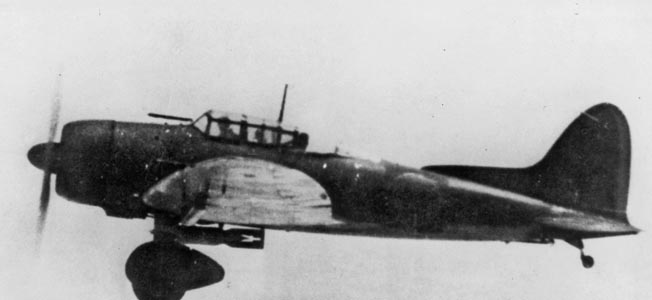

The first-wave fighters wasted no time. Ironically, the opening aerial combat of the Pearl Harbor attack involved a civilian aircraft. One minute after Fuchida’s “Tora!” message, several Zeros from the carrier Akagi stumbled across a Piper Cub flown by solo student Marcus F. Poston. Unable to resist the temptation, the Zeros opened fire with their two 20mm cannon and two 7.7mm machine guns, ripping the Cub’s engine from its mount. The startled but lucky student pilot leaped unhurt from his plane for his first and only parachute jump. Zero pilots Takeshi Hirano and Shinaji Iwama shared the kill.

Running Into a War

Genda’s brilliant and bold plan, executed to perfection by Fuchida’s first wave, unfolded without a hitch. Between 7:55 and 8:10 a host of Val dive bombers escorted by Zeros laid waste to the two major military air bases on Oahu. Attacking from different quadrants, 25 Vals dropping 550-pound bombs turned Wheeler Field into a raging inferno. The Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighters on the tarmac of the 14th Pursuit Wing offered a particularly inviting target. By order of U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, commander of the Hawaiian Department, all aircraft at Wheeler and Hickam Fields were parked wingtip to wingtip in precise rows, ostensibly to facilitate guarding against sabotage.

Rampaging Vals and strafing Zeros found easy pickings. They destroyed 58 fighters on the ground and damaged another 37. At Hickam only 19 of 58 bombers from the 18th Bombardment Wing survived the attack. Simultaneously, huge columns of black smoke boiled above Pearl Harbor where Type 91 Model 2 Japanese torpedoes had already smashed into the battleships Oklahoma, West Virginia, Arizona, and California.

Into this maelstrom of devastation and confusion stumbled the 12 B-17s of the 38th and 88th Reconnaissance Squadrons, led by Major Truman H. Landon. Contrary to a widespread contemporaneous view, they did not make the 13-hour trip in formation; each of the four B-17Cs and eight B-17Es flew and navigated separately, their flights beginning at Hamilton Field, California, about 25 miles north of San Francisco.

Emphasizing the importance of the mission to the Philippines by way of Honolulu, no less a personage than Chief of the Army Air Forces General Henry “Hap” Arnold was there to see them off. Interrupting a quail hunting trip to address the crews, he warned them, “War is imminent. You may run into a war during your flight.” Armed with that admonition but nothing else, the big bombers began taking off at 10:30 pm. The prevalent feeling was that a war would not erupt until after they reached the Philippines. Therefore, none of the ships carried armor or ammunition; they were stripped down and packed to the brim with every gallon of fuel they could carry for the long hop from California to Hawaii. The B-17 Flying Fortresses did in fact carry their potent arsenal of .50-caliber machine guns, but they were boxed, stowed away, and packed in Cosmoline.

As Major Landon’s B-17E approached Oahu from the north at approximately 8 am, he observed a group of planes flying toward him. His first thought was, “Here comes the Air Force out to greet us.” Seconds later the unidentified aircraft dived on Landon, cannon and machine guns blazing. Over the intercom the crew heard someone say, “Damn it, those are Japs!”

Landing Under Fire

To evade the attackers, Landon skillfully flew into a nearby cloud bank, then took up a heading for land. As Landon maneuvered his bomber on the short final run to the Hickham runway, the tower operator advised, “You have three Japs on your tail!” In spite of the hail of fire coming his way, somehow Major Landon managed to get his bird down in one piece. Following right behind Landon, another B-17E appeared through the heavy smoke and touched down. Not believing his eyes, the pilot, Lieutenant Karl T. Barthelmess, thought it was the most realistic drill he had ever seen.

Captain Raymond T. Swenson and crew were not so lucky. After one aborted approach, the pilot positioned his B-17C for a second attempt at Hickam’s runway. At that point a Zero piloted by Lt. Cmdr. Shigeru Itaya riddled the aircraft at point-blank range, sending several bullets into the radio compartment and igniting a bundle of magnesium flares. The Flying Fortress was engulfed in flames when it touched down, and halfway through the landing roll the incinerated fuselage broke in half just behind the wing root. The crew jumped from the burning wreck and ran across the field for cover. All made it except one. The squadron flight surgeon, Lieutenant William R. Schick, was gunned down by a strafing Zero. He died the following day at Tripler Army Hospital.

After repeated Japanese fighter attacks, 1st Lt. Robert H. Richards gave up trying to land in the shambles at Hickam and headed east. Dangerously low on fuel with three wounded crewmen aboard and heavy damage to the ailerons of his B-17C, Richards guided his aircraft in for a downwind landing on the short runway at Bellows Field, a fighter strip on Oahu’s southeast coast. Richards flared out and touched down at approximately midfield on the short strip. Realizing he would not be able to stop, he retracted the wheels and slid off the runway over a ditch and into a sugarcane field bordering Bellows. Maintenance crews counted 73 bullet holes in the plane.

First Lieutenant Frank P. Bostrom also discovered that Hickam, under heavy dive bombing and strafing attacks, was a less than inviting choice for landing. After his B-17E was harassed by nine Zeros, he headed west for Barbers Point, only to be driven off by more Japanese fighters. Desperate to land anywhere and sincerely believing that necessity really was the mother of invention, Bostrom finally set his damaged B-17 down on a fairway at the North Shore’s Kahuku Golf Course. In addition to one Flying Fortress on the golf course and one at Bellows Field, two other B-17s slipped into Haleiwa’s small fighter strip. The remaining eight staggered into Hickam, although one Flying Fortress apparently landed at Wheeler before relocating to Hickam. All were on the ground by 8:20 am. To a man, each crewmember vividly recalled General Arnold’s prophetic warning: they had indeed run into a war.

SBDs Take on the Zeros

While Major Landon and his B-17s were mixing it up with Japanese aircraft over Hickam Field, 18 U.S. Navy Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers in nine flights of two aircraft each approached Oahu’s west coast. The aircraft from Scouting and Bombing Squadrons Six had launched from the carrier Enterprise at 6:18 that morning en route to Ewa and Ford Island. Their mission was to scout ahead of the Enterprise on a 90-degree sector search from 045 degrees to 135 degrees for 150 miles, then practice navigation by homing in on radio station KGU’s signal. Between 8:15 and 8:30 am, they flew directly into the gunsights of marauding Zeros from the carrier Soryu. An ominous radio transmission from one of the SBDs set the tone. Over their radios most of the squadron members of Scouting Six and Bombing Six heard the voice of Ensign Manuel Gonzales shout, “Do not attack me. This is Six Baker Three, an American plane!” Gonzales and his radioman/gunner, Leonard J. Kozelek, were never seen again.

Although the SBD Dauntless was no dogfighter, it did have some teeth. It sported two .50-caliber machine guns in its nose cowling and a .30-caliber machine gun manned by the radioman/gunner in the rear cockpit. Ensign John H.L. Vogt armed his guns and unhesitatingly flew his SBD-2 into a group of first-wave aircraft forming up for the return flight to their carrier. Marines on the ground at Ewa watched in amazement as Vogt tangled with a Zero in a twisting, turning fight from 4,000 feet down to just 25 feet above the ground. Marine Lt. Col. Claude Larkin, commander at Ewa, witnessed the battle. According to Larkin, during one of the abrupt turns the Dauntless and the Zero collided. Vogt and his radioman/gunner, Sidney Pierce, managed to bail out, but they were too low. Both perished when their parachutes failed to fully deploy. Subsequent investigations of Japanese combat records revealed that there was a near miss but no collision; only three first-wave Zeros were lost and none in the vicinity of Ewa. Vogt’s SBD-2 apparently went down under the guns of a Soryu Zero piloted by Shinichi Suzuki.

At that point another Enterprise flight of SBDs was approaching Barbers Point from the south. Lieutenant Clarence E. Dickinson and his wingman, Ensign John R. McCarthy, were cruising at 4,000 feet when McCarthy spotted two Zeros. He slid under Dickinson so his gunner could get a better shot at the approaching fighters, but that move placed his aircraft in the direct line of fire. McCarthy’s SBD-2 instantly began smoking and crashed, killing his radioman/gunner, Mitchell Cohn. McCarthy managed to bail out, suffering a broken leg when he landed.

Now without a wingman, Dickinson was attacked by four enemy planes. He managed to get in two short bursts from his guns when a Zero overshot, and his backseater, William C. Miller, damaged one of the Zeros while the others hammered his plane from the rear. Miller apparently died or was incapacitated in the deadly exchange. With his left fuel tank on fire and his controls shot away, Dickinson attempted a hard turn to the right away from his attackers, but the SBD-3 went into a spin. He “hit the silk” at approximately 1,000 feet. Fortunately, he landed unhurt on a dirt embankment just east of Ewa. From there the resourceful naval aviator, dragging his parachute, walked to the main road and hitched a ride with Mr. and Mrs. Otto Hein, who happened to be driving by in their blue sedan. They had no idea that a battle was raging above them. The middle-aged couple turned around and drove Lieutenant Dickinson to Pearl Harbor.

Two more SBDs went down during the first wave. Over Barbers Point, Zeros pounced on Ensign Walter M. Willis and his gunner, Fred J. Ducolon. No trace of either man has ever been found. The final victim was Ensign Edward T. Deacon, shot down by friendly ground fire from Army troops stationed at Fort Weaver near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. Deacon ditched in shallow water several hundred yards from the beach. He and his radioman/gunner were rescued.

The Pineapple Air Force

The Japanese attack had caught the Hawaiian Air Force, affectionately known as the Pineapple Air Force, completely by surprise. General Short had received a war warning message on November 27 from Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall advising, “Hostile action possible at any moment…” and further directing Short “to undertake such reconnaissance and other measures as you deem necessary.” At that point all Hawaiian Army units went on full alert and languished there for a week. By the morning of December 6, General Short elected to stand down and give his men the weekend off.

Marshall’s war warning proved prophetic. When the attack materialized 10 days later and caught the chain of command napping, a handful of individual Army Air Force pilots got airborne on their own initiative and engaged the enemy, but there was no coordinated defense. The few serviceable aircraft were launched piecemeal as pilots arrived to fly them.

Just before 8 am, when the first Japanese bombs exploded among the parked aircraft at Wheeler Field and shattered the Sunday morning calm, two second lieutenants, “brown bars” only a few months out of flight school, sprang into action. Kenneth M. Taylor from Hominy, Oklahoma, and George S. Welch from Wilmington, Delaware, were still a little groggy from a round of Saturday night partying. Sporting tuxedos and white dinner jackets, the lieutenants had begun the evening at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel before moving on to a dance at the Hickam Officers’ Club. From there they adjourned to the Wheeler Officers’ Club for a late-night poker game before turning in around 3 am.

At the sound of the first bombs, Taylor staggered out of bed and hastily dressed in the nearest apparel, tux trousers and formal shirt. Immediately he ran into the street and met Welch, who shouted, “What the hell is going on? Those son-of-a-bitches are bombing the hell out of us!”

Both young lieutenants realized that a war had started, but they were not exactly sure with whom. Dumbfounded by the catastrophe unfolding before his eyes, Taylor eventually had the presence of mind to call Haleiwa, the auxiliary field on the North Shore where his squadron’s P-40B fighters had been bedded down, and direct them to get the planes ready for immediate launch. With that, both men jumped into Taylor’s red Buick and raced to Haleiwa about 10 miles away. The field had been fortuitously overlooked in Genda’s attack plan.

America’s First Aerial Victory

On arrival the Army pilots hurriedly strapped into their P-40s and took off. Right behind them, 2nd Lt. John Dains arrived in another car and took off in the next available P-40. Although many historians and newspapers credit Taylor and Welch with America’s first aerial victory of World War II, there is a strong possibility that Dains may own that honor. Early in the second wave, radar operators at Ka’a’awa on the windward coast watched as Dains engaged in a vicious dogfight with a Val piloted by Satoru Kawasaki and shot his opponent down. Unfortunately, as Dains returned to Wheeler from his second sortie, this time flying a P-36 fighter, trigger-happy gunners at Schofield Barracks opened fire and killed him.

When Taylor and Welch took off from Haleiwa, for unknown reasons only the four wing-mounted .30-caliber machine guns in each plane were loaded. The plane’s two .50-caliber machine guns were not. Although estimates vary widely, the two lieutenants probably got airborne around 8:55 with instructions to patrol over Barbers Point. Finding nothing there, Welch, nicknamed “Wheaties,” spotted about a dozen aircraft circling over the Marine airfield at Ewa.

Using Taylor’s nickname, Welch shouted, “Hey Grits, I see Jap bombers down there just like sitting ducks.” With that, both pilots put their P-40s into screaming dives and closed on the circling Val dive bombers. The novice fighter pilots simply dropped into line behind the wagon wheel formation, picked individual targets, and began firing. Welch lined up a Val in his sights. With only three of his four guns firing, he sent a long burst into his opponent and watched as the smoking Val tumbled out of control and fell to earth.

In an interview shortly after the fight, Welch described the action over Ewa: “Their rear gunner was apparently shooting at the ground—because they didn’t see us coming. I got him in a five-second burst—he burned up right away.” Welch was credited with the victory, but years later further investigation indicates that in the chaotic combat Hiroyasu Kawabata’s Val recovered on the deck and was able to limp back to the Hiryu.

Taylor brought down the first plane he engaged. He noted, “It was a short burst but the guy immediately exploded into flames and rolled over. All I could see were those two fixed landing gear sticking up. He crashed very close to Ewa.”

Confusion in the Fog of War

After watching the first Val plummet toward the ground, Welch went vertical by executing a loop and lined up another D3A in his sights. Welch explained, “I left him and got the next plane in a circle which was about one hundred yards ahead of him. It took about three bursts of five seconds each to get him. He crashed on the beach.”

While Welch’s .30-caliber machine guns ripped Hajime Goto’s Val apart, the rear seat gunner returned fire, forcing Welch to break off. At that point Japanese sources claim that Taylor opened fire on the same Val, wounding the gunner and scoring more hits on the enemy plane.

In the confusion and unaware of Welch’s duel with Goto, Taylor’s account of the action stated, “With my first burst I killed his rear gunner, and then began to pour it into the Jap. Black smoke began to stream out of him and he started to lose altitude fast. I didn’t want to get too far out to sea, so I headed for Wheeler Field, and I didn’t see this fellow crash.”

Army officials saw it differently. In view of the fact that Welch’s deadly fire had raked Goto’s Val and that he observed the aircraft crash, they assigned credit for the victory to Welch.

The duo of Taylor and Welch latched onto other Vals and saw them smoke but never witnessed the crashes. Low on ammunition, Grits and Wheaties broke off the engagement and individually set course for Wheeler.

Over the years the exact time and details of the Taylor and Welch combat over Ewa have been repeatedly analyzed and in some cases questioned. Clearly the proverbial “fog of war” and lax record keeping contribute to the confusion, but the two pilots inadvertently fed the fires of controversy themselves. In testimony on December 26, 1941, before the Roberts Commission investigating the Pearl Harbor attack, Taylor related somewhat confusing details about what happened on December 7.

Taylor testified that after getting airborne from Haleiwa, “Lieutenant Welch and myself started patrolling the Island. There wasn’t any .50-caliber ammunition, so we landed at the field [Wheeler].”

Taylor never mentioned the battle over Ewa. Moreover, both pilots’ descriptions of combat to the Roberts Commission focused on their second sortie, leaving the impression that all the action had occurred after the wild launch out of Wheeler. Any inconsistencies were officially put to rest when the citations awarding Taylor and Welch the Distinguished Service Cross included the Haleiwa to Ewa combat sequences.

Rearming For a Second Sortie

After landing at Wheeler, Taylor and Welch quickly climbed back into their rearmed P-40s for a second mission. They got airborne just as a Japanese second-wave formation bored in on the field, and according to eyewitnesses Taylor began firing his guns while still on takeoff roll. Once in the air, Taylor immediately began pouring machine-gun fire head-on into a Val, only to be jumped from behind by a second Val piloted by Saburo Makino. One of Makino’s bullets shattered Taylor’s canopy and went through his left arm, hit the metal trim tab, and then sent a dozen pieces of shrapnel into his legs.

Taylor broke into a high G turn in an effort to lose his foe, and then Welch came to the rescue. To keep from overshooting Makino’s Val, Welch resourcefully lowered his flaps and began pummeling his opponent with .50-caliber machine-gun fire. Mrs. Paul Young, standing in the door of her house in Wahiawa, watched as Welch blasted the Val. Makino’s D3A pitched down, shearing off the top of the eucalyptus tree in her backyard before it crashed into a nearby pineapple field. This was Welch’s third confirmed kill of the day; a few minutes later he downed a Zero off Barbers Point.

With his 6 o’clock clear, Taylor engaged a Val flown by Iwao Oka. In spite of a blistering volley from the rear-seat gunner and wounds to his arm and legs, Taylor attacked Oka’s aircraft mercilessly, sending the Val crashing into the ground near the entrance to a Civilian Conservation Corps camp.

Attack on Kaneohe Naval Air Station

At Haleiwa Lieutenants Harry W. Brown and Robert J. Rogers of the 47th Pursuit Squadron each took off in obsolete P-36s, an earlier version of the P-40 fitted with a radial engine. They headed for Kaena Point, the westernmost tip of Oahu, where Rogers encountered a mixed flight of Japanese aircraft. When two enemy planes singled Rogers out, Brown, from Amarillo, Texas, dived into the fight, shooting down one of the attackers. Rogers poured a long stream of tracers into the other aircraft, which smoked and fell away, but he did not see it crash. Brown then joined up with Lieutenant Malcolm A. Moore’s P-36 and engaged two departing Zeros. Neither enemy fighter was seen to crash, but neither made it back to its carrier.

On the opposite side of the island, the battle turned tragic for the P-40 pilots of the 44th Pursuit Squadron. A flight of nine Zeros led by Lieutenant Fusata Iida had just wreaked havoc on Kaneohe Naval Air Station before moving south to Bellows. Several of the Marine ground crews at Kaneohe extracted a measure of revenge when they poured multiple Browning automatic rifle magazines into Iida’s fuel tank. Realizing he could never make it back to his carrier, Iida elected to dive his Zero into the Kaneohe base armory. Instead, his plunging aircraft struck a glancing blow on a street and then skidded into an earthen embankment. Later, Iida’s mangled remains were removed from the wrecked aircraft and placed into a garbage can—not out of disrespect but because that was the only thing available. Iida’s body, along with the bodies of 16 Americans, was left outside the sickbay entrance.

Then, at 9 am, as three young pilots sprinted for any undamaged parked aircraft on the Bellows tarmac, the remaining Zeros from Iida’s group strafed the ramp, killing 2nd Lt. Hans Christenson as he climbed into his P-40B. Two other lieutenants from the 44th Pursuit Squadron, George A. Whiteman and Samuel W. Bishop, gunned their engines on a hair-raising takeoff scramble. Before Whiteman got 100 feet into the air, a Zero piloted by Tsuguo Matsuyama blasted the vulnerable fighter with a burst right into the cockpit; the P-40 crashed into the sand dunes at the end of the runway and exploded. Bishop’s P-40 attained 800 feet of altitude before a Zero literally pounded it into the ocean. Bishop crashed about a half mile off shore but got out of the wreckage and was able to swim to the beach.

Four P-36s at Wheeler

Back in the shambles at Wheeler, Lieutenant Lewis M. Sanders of the 46th Pursuit Squadron found four serviceable P-36s and a ragtag collection of pilots to fly them. Second Lieutenants Phillip M. Rasmussen, John M. Thacker, and Gordon M. Sterling each jumped into the cockpit of a P-36. As he strapped in, Sterling, from West Hartford, Connecticut, handed his wristwatch to the crew chief and said, “See that my mother gets this. I won’t be coming back.”

At approximately 8:50, Lieutenant Sanders got his flight airborne between the first and second waves and headed east toward the naval air station at Kaneohe. From his altitude of 11,000 feet, Sanders spotted a formation of enemy aircraft, six Soryu Zeros about to join up with the same Hiryu Zeros that had ravaged Bellows. With no hesitation, the Americans dived into the numerically superior force.

At 9:15 Sanders opened fire on the leader and observed his tracers tear into the Zero’s fuselage. The plane nosed up then fell off to the right smoking. After executing a fast clearing turn, Sanders saw Gordon Sterling in a near vertical dive pouring deadly fire into a Zero. But a second Zero latched onto Sterling’s tail and peppered him with 20mm cannon fire. Sanders executed a diving turn with plenty of angle-off and engaged that Zero at maximum range.

In a terrifying scene, the line of four aircraft—Zero, Sterling’s burning P-36, Zero, Sanders—disappeared into an overcast. In his combat report Sanders stated, “The way they had been going, they couldn’t have pulled out, so it was obvious that all three went into the sea.” Ultimately, however, Japanese records showed that only Sterling went into Kaneohe Bay. The two Zeros, although badly damaged, made it back to the Soryu.

The Pilots That Caused the Japanese to Lose 29 Planes During the Pearl Harbor Attack

Arguably, the title of luckiest pilot of the day belonged to Lieutenant Phil Rasmussen, a native Bostonian. As he dived into the dogfight as part of Lew Sanders’s flight, Rasmussen, flying in purple pajamas, charged his machine guns only to have them malfunction and begin firing on their own. At that precise moment a Zero passed directly into his runaway machine-gun fire and exploded. Only a minute or two later Rasmussen was jumped by two Zeros that laced his P-36 with a volley of devastating machine-gun and cannon fire. The enemy barrage tore off his tail wheel, severed his rudder cables, and shattered his canopy. Rasmussen only escaped by ducking into a convenient cloud.

A handful of other Pineapple Air Force pilots saw action on that Sunday morning before Commander Fuchida rounded up the second wave and departed around 10 am. The 19 Army Air Force pursuit pilots who got airborne during the attack downed 11 Japanese aircraft, claimed five probables, and damaged at least two others. The Japanese confirmed losing 29 aircraft over Oahu during the Pearl Harbor attack, and they were forced to jettison an additional 19 aircraft from their carriers because of extensive battle damage. On December 11 the Honolulu Star Bulletin published an article attributed to General Short declaring that Army fliers downed 20 Japanese aircraft during the attack.

Four to One Against the Zeros

Without question the American pilots and airmen who squared off against the Japanese in aerial combat at Pearl Harbor faced overwhelming odds, danger, and mass confusion. In spite of the chaos and turmoil, the relatively small number of inexperienced young lieutenants gave better than they got, and ironically nobody told them not to dogfight with nimble Zeros or Vals. Instead, they tackled their opponents in classic one-on-one air battles.

Many historians accept as a matter of faith that early in the war the Mitsubishi Zero maintained a high victory ratio against mediocre American fighters like the P-40 Warhawk. The statistics in general and Pearl Harbor in particular suggest a different conclusion. Although George Whiteman and Sam Bishop both fell prey to the vaunted Zero, they were on takeoff leg and in no position to bring their guns to bear. Lieutenant Gordon Sterling was the only pursuit pilot actually brought down in air-to-air combat with a Zero, whereas the American pilots flying supposedly inferior equipment downed at least four Zeros and two probables, thereby punching the first holes in the Zero’s aura of invincibility.

Unfortunately, most Americans have no knowledge of these meager yet significant aerial victories and remember Pearl Harbor only as an unmitigated naval disaster. Perhaps a comment by Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, commander of the Pacific Fleet on December 7, best captures that gloomy sentiment. Watching the attack from his office window, Admiral Kimmel flinched when a spent bullet crashed through the glass, striking him on the chest and leaving a dark smudge on his white uniform. Picking up the bullet, he muttered, “It would have been merciful had it killed me.”

There was no such negative sentiment among the surviving American fliers of that Sunday morning. A more appropriate mind-set for the fliers who battled above Pearl Harbor is captured in Winston Churchill’s epic observation, “If you’re going through hell, keep going!” They did. The Army Air Force crews and naval aviators engaged in aerial combat over Oahu, while unable to change the course of the battle, wrote the first American chapters in the World War II handbook on war in the air. They set the bar high and defined the aggressive spirit of American warriors who kept fighting in the face of overwhelming odds.

Originally Published February 21, 2017.

Seemingly forgotten is Sgt Charles Petrakos, 4th Reconnaissance Sqdn, 5th Bomb Gp (B-18/B-17E/F), who shot down two attacking Japanese planes from the nose of a burning bomber on the Hickam Field flight line.

He was awarded a Silver Star for his action-(could they spare it?). Later, it appears that the citation to accompany the award had been edited and lines had been deleted.

He rarely spoke of the events of the attack his entire life, died in 2003 at the age of 86.

He was my uncle.

Respect.

Oh wow. God rest his soul. ‘Til Valhalla.

When I visited Oahu we stayed in Halewa on the North Shore in the mid 1990’s. At that time I briefly read about the “Hawk of Halewa” & assumed it was one of the pilots that got airborne from Halewa field. After all these years this article has finally made me realize that it wasn’t a nickname for a single pilot as I initially thought it was but is in fact a reference to the P40 Warhawk & P36 Mohawk aircraft that the five pilots managed to get off the ground that day. The famous painting depicts a P-36 Mohawk whose Halewa pilots shot down 3 Japanese planes, the remaining 6 Japanese planes shot down by Halewa pilots that day were credited to P-40 Warhawks. A great read, thanks for posting this mostly forgotten part of the Pearl Harbor attack story.

the mohawk was the name the Royal Air Force gave the p-36 when they acquired a number of curtiss Hawk 75s (the export version of the p-36) which were flown to britain after the fall of france in 1940. since the british did not return the export versions to the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) i don’t believe p-36s were called mohawks when they were in hawaii. Sorry but i am afraid that you are mistaken.

I remember an aircraft crash site on McCully St, just a few blocks south of King St. It was the only plane that I know of which has crashed in Honolulu.

i would not say that the P40 was a mediocre aircraft while it was not as good a plane as the hell cat or the corsair it was a good aircraft that served well though out the war