By Glenn Barnett

The Japanese empire was a fine place for young Hiro Onoda. In 1939, at age 17, he hired on with a lacquerware company that posted him to Hankow (Wuhan) in Japanese-occupied China. There, he visited suppliers by day and danced the night away with obliging Chinese women.

His idyllic world, along with that of countless others, came to an abrupt end in December 1941.

Japan opened up a new front in her war against the rest of the world. The Army desperately needed manpower. Onoda was called up in May 1942, and after basic training he was accepted into officer’s candidate school. Upon graduation, he was promoted to 2nd lieutenant and selected for special training in a pacification squad, a type of commando unit.

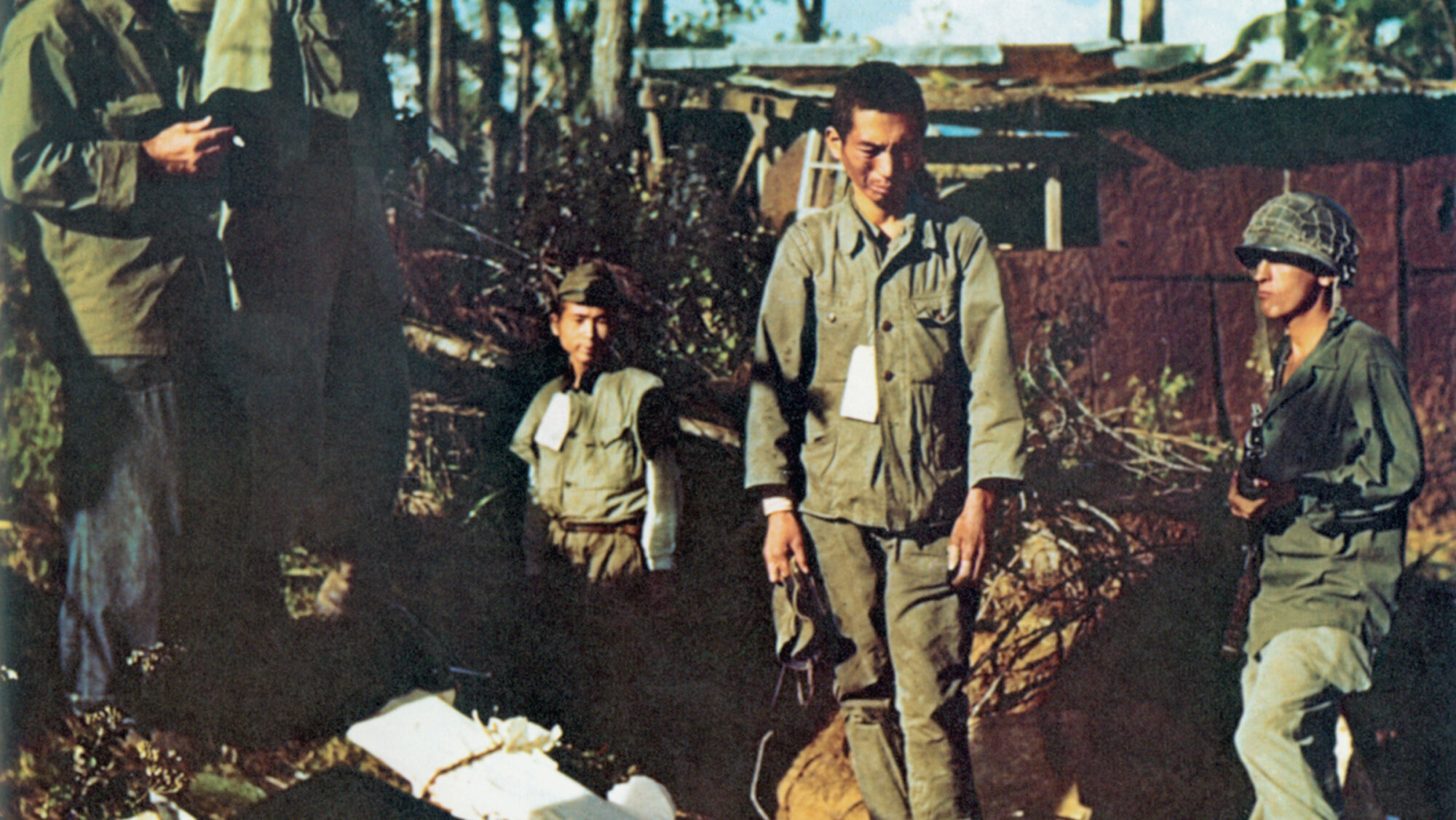

In December 1944, with the American enemy growing in strength and resolve, Onoda was sent to the Philippines. There, he was ordered to connect with a local Japanese garrison and conduct reconnaissance of enemy strength and dispositions. He was also instructed to conduct guerrilla warfare after the expected American invasion. Under no circumstances was he to give up or commit suicide. Of the millions of combatants of every nation in World War II, no soldier was more faithful to his orders than Lieutenant Hiro Onoda of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Thank you for this interesting, informative, and confounding article.

This informative article was fascinating. Thank you for your scholarship and fine writing. They are amazing stories!