By David H. Lippman

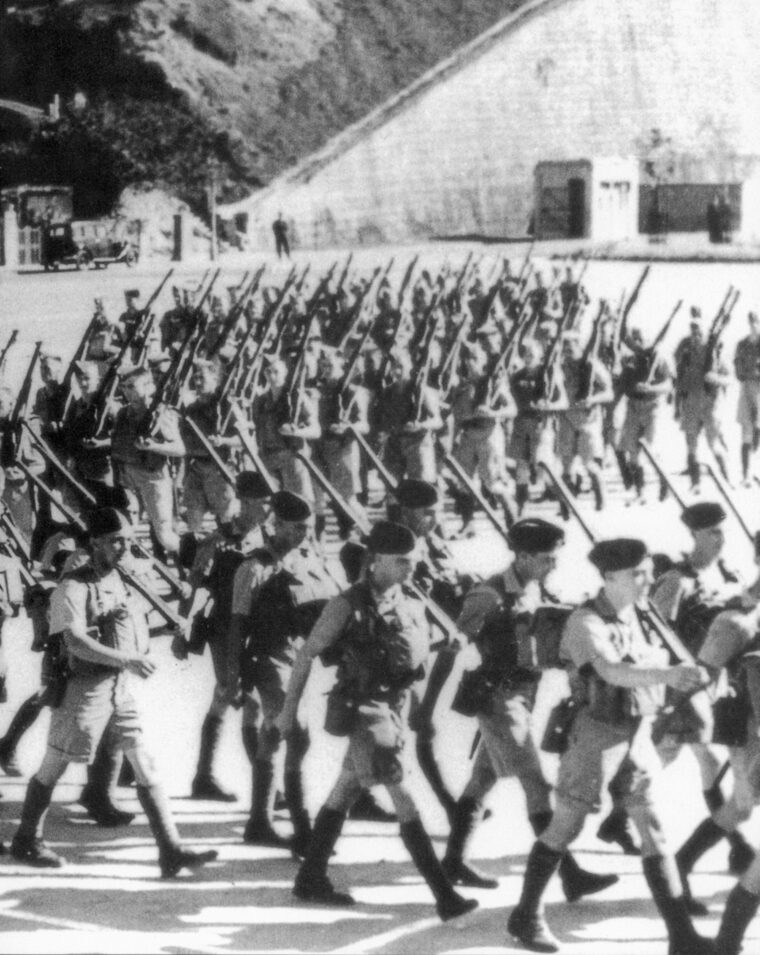

With rhythmic tread, the Canadian soldiers marched behind the bagpipers of the Royal Scots up Nathan Road. All along Kowloon’s main shopping street, European and Chinese civilians cheered and applauded the Canadians. Hong Kong’s Chinese and European population knew that the two battalions would be more than enough to protect them from Japanese invasion. It was November 16, 1941, 40 days before Christmas, and 40 days from defeat and surrender to the Japanese.

Hong Kong, cut off from China by Japanese forces, had a population of 1.2 million, including more than a million Chinese refugees from the Sino-Japanese War. The 20,000 Britons who administered Hong Kong or dominated its commerce lived in luxury in Victoria and the Peak, with servants, restricted clubs, new air-conditioners, and garden parties.

Down below the Peak, Chinese residents lived in poverty, doing backbreaking jobs. Many were illiterate, living 12 to a room, or even on the streets. Every morning, one-ton government trucks rolled through grubby neighborhoods in Wanchai or Kowloon to empty public outhouses or pick up the bodies of refugees who had died of illness, starvation, or violence.

Nonetheless, how Britain’s obligation to defend Hong Kong was to be met was a source of controversy in Whitehall. In early 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided that Hong Kong was impossible to hold and suggested that its defenses be reduced to a symbolic level, saying: “We must avoid frittering away our resources on untenable positions.”

A 1938 assessment by the General Officer Commanding, General A.C. Bartholomew, was equally harsh: “The chances of effecting a prolonged resistance even in the best circumstances seem slight.”

But Bartholomew’s successor, Maj. Gen. A.E. Grasett, disagreed. He believed the Japanese forces that sealed off Hong Kong to the north were inferior to the British forces. When he flew back to London in September 1941, after being replaced by Maj. Gen. Christopher Maltby, Grasett convinced the War Cabinet that Hong Kong could be held if it was reinforced with two battalions of infantry, possibly Canadian units.

At the time, Hong Kong’s defenses consisted of two Indian infantry battalions (the 5/7th Rajputs and the 2/14th Punjabis) and a British infantry battalion, the 2nd Royal Scots. The 1st Middlesex, a machine-gun battalion, backed them up. The defenders also fielded the Hong Kong Volunteer Regiment’s reservists, two regiments of fixed coast artillery, and the Hong Kong and Singapore Artillery Regiment’s mobile guns.

The 2nd Royal Scots had served the Crown since 1633, but the regiment’s best men were serving in England. Most of the 2nd Battalion suffered from malaria. The 5/7th Rajputs and the 2/14th Punjabis were also veteran outfits, but their best men had also been “milked” for Indian forces in the Middle East. Some 40 percent of the Rajputs had just joined the battalion. Some Punjabis had yet to see even a 3-inch mortar, let alone fire one.

The Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps’ manpower reflected Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan nature, with companies of Free Frenchmen, Russians, Portuguese, Scandinavians, and Americans. There was even a company of men aged over 55. The best unit in Hong Kong was the 1st Middlesex, “The Die-Hards” of Peninsular fame, which had spent 10 years overseas. Well trained and full of “Old Sweats” from London’s East End, it was equipped with Vickers machine guns.

The Volunteers were a colorful outfit, under Colonel Henry Rose, a 30-year veteran and one of the few surviving “Old Contemptibles” of 1914, and Regimental Sgt. Maj. “Wacky” Jones. Playing at soldier was great fun and a means of social climbing for the Volunteers.

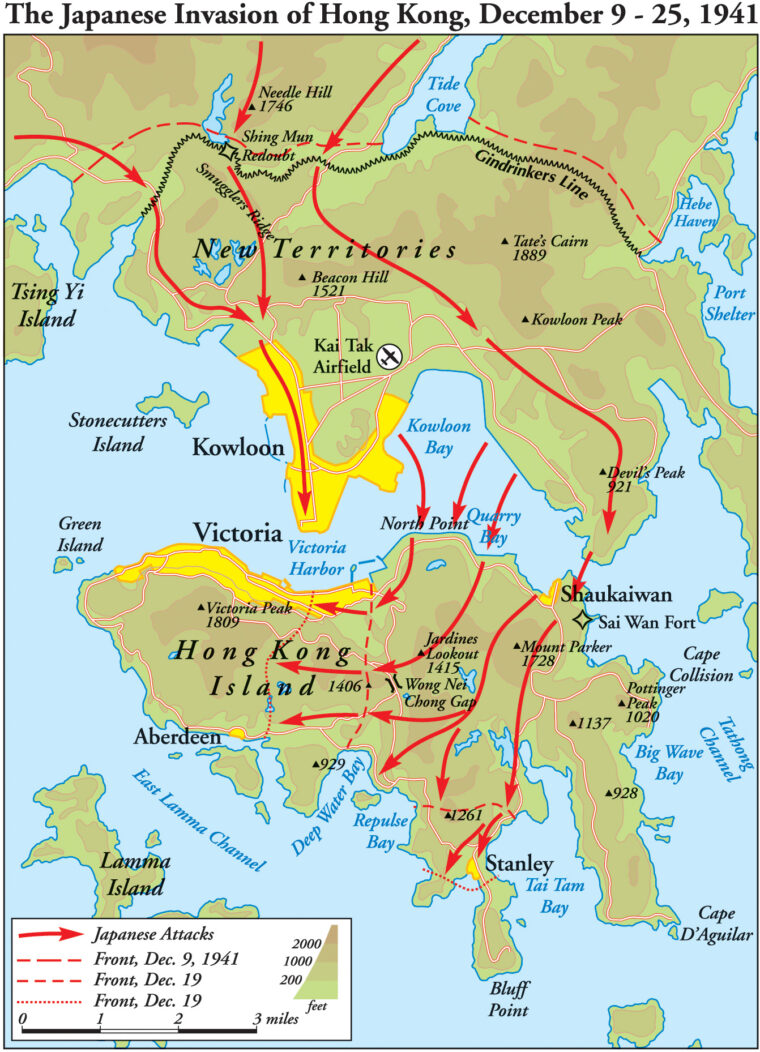

The key to holding Hong Kong was a string of pillboxes and trenches along the hills just north of Kowloon, named the “Gindrinkers Line” for its terminus at Gindrinkers Bay in the west. The strongpoint of this line was the Shing Mun Redoubt at the southern end of the Jubilee Reservoir, which overlooked the bottleneck of roads that led to Kowloon. The redoubt consisted of several bunkers and observation posts, connected by trenches, tunnels, and staircases covered with concrete, all named for London streets such as Haymarket and The Strand. Shing Mun’s five pillbox embrasures were so constructed that it was impossible to depress a Bren gun low enough to cover the hill’s steep slopes. The craggy terrain offered attackers numerous ravines for cover and prevented the pillboxes from giving each other covering fire. Shing Mun was designed to be held by a full rifle company for at least a week.

Shing Mun was no Maginot Line, but Grasett said it didn’t have to be. With three infantry battalions, Hong Kong could be held against attack from the north. Two more infantry battalions and the machine-gun battalion would man defenses on Hong Kong Island to prevent seaborne invasion. Maltby shared Grasett’s view, and the War Cabinet was sold. On September 15, 1941, Churchill agreed to a proposal by the Chiefs of Staff that Canada provide two battalions and a brigade headquarters.

So far Canada’s Army had seen no action, and there was political pressure to get them into the fight. With all first-line Canadian battalions earmarked for Europe, the only outfits available were those that had not been fully trained. Two of these were the Royal Rifles of Canada, a French-speaking outfit from Quebec, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers. The Royal Rifles had spent most of the war patrolling Newfoundland to prevent Nazi U-boats from landing spies and saboteurs. The Winnipeg Grenadiers were in Jamaica, guarding a POW camp. Many of the men in the two battalions had never fired a mortar or thrown a grenade. But there were no other available battalions in Canada.

To fill the battalions up, Canadian authorities assigned them 436 reinforcements, which included 16- and 17-year-olds with less than six weeks’ service. Captain Wilfred Queen-Hughes, a Grenadier transport officer, was shocked. “We got the odds and sods. Literally the sweepings of the depots. Men no other command had wanted and rejected. There was even a hunchback!” The two battalions were shipped by rail to Vancouver.

The Royal Air Force at Hong Kong had only three ancient Vildebeeste torpedo bombers (which flew at less than 100 mph) and two Walrus amphibians.

The Royal Navy had withdrawn most of the China Squadron, leaving behind Commodore George Collinson commanding the old (1918) destroyer HMS Thracian, the eight gunboats of 2nd Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla, and four river gunboats. The MTBs could do 32 knots but leaked, were cramped, and had no torpedoes. Instead they were armed with machine guns.

Eight fixed 9.2-inch guns and 15 6-inchers prevented seaborne invasion, but the mobile artillery was outdated. On paper, Hong Kong was to have 32 heavy and 30 light antiaircraft guns, but only 14 heavy and two light were on hand, with no radar.

In Canada, Colonel John Lawson, a decorated World War I veteran, was promoted brigadier and appointed to command the force. Lawson, who had risen from private in the 101st Edmonton Fusiliers to field rank, was a 51-year-old who studied military history. Lawson did not share his superiors’ contemptuous view of the Japanese. He believed that they were a powerful force.

He was right. British intelligence believed the Japanese had only 3,000 men over the frontier. They actually had closer to 25,000 attackers in the 23rd Army, under Lt. Gen. Takashi Sakai, a 52-year-old factory worker’s son with six years’ experience in China. The attack was assigned to the reinforced 38th Infantry Division, under Lt. Gen. Sano Tadayoshi.

The 38th Division was organized in September 1939, in Nagoya. It was backed up by all of the 23rd Army’s artillery—the 1st Siege Regiment with 150mm howitzers, the 20th Independent Mountain Artillery Battalion, the 21st Independent Mortar Battalion, two antitank battalions, and the 38th Engineer Regiment.

Air cover consisted of a squadron of Ki-43 Nate fighters, another of Ki-36 Ida light bombers, and one of Ki-48a Lily attack planes.

The Japanese consulate in Hong Kong provided useful information on the location of pillboxes and guns. When British counterintelligence pulled the plug on them, the Japanese turned to more romantic means of spying, such as Wanchai prostitutes … a Japanese jeweler in the Queen’s Arcade … an Italian waiter at the Peninsula Hotel … and the Japanese barber at the Hong Kong Hotel. The Japanese also infiltrated hundreds of Chinese fifth columnists, with orders to commit acts of sabotage and sniping.

Sakai’s plan to take Hong Kong was simple. The 38th Division would cross the border on X-day. The 230th Infantry Regiment was to swing right and hit the Shing Mun Redoubt. The 228th Regiment would hit the center of the Gindrinkers Line and grab Kai Tak Airfield. The 229th Regiment on the left would cross Tide Cove in sampans, break through the defenses, and reach Kowloon Bay.

Speed was the vital factor. As soon as Hong Kong was secured, the 38th’s next destination was the Dutch East Indies and its vital oil fields, by Christmas Day.

While the Japanese planned, the Canadians sailed for Hong Kong, leaving Vancouver on October 27 on the transport Awatea and the escorting cruiser HMCS Prince Robert.

Awatea could not accommodate Lawson’s 212 vehicles, which included 104 trucks, 57 Bren carriers, and 45 motorcycles. The vehicles were loaded on the American freighter Don Jose a week later. It reached Manila in the Philippines on December 12, when the vehicles were stranded by the outbreak of war. General Douglas MacArthur requested the vehicles for his command, and the defenders of Bataan wound up using them.

On Sunday, November 16, Awatea sailed into Hong Kong, greeted by three RAF planes and five MTBs.

After that, the Canadians settled in. By day, they dug trenches, manned pillboxes, attended lectures, and square-bashed (performed close-order drills). Private George Merritt of the Winnipeg Grenadiers bought a Chinese girl from her family for $10 a month. She did his laundry, shined his shoes, and shaved him in her family home, while her mother cooked dinner. Grenadier Private Ted Schultz and his buddies got drunk in bars and slugged it out with Royal Rifles, to the dismay of the Military Police. Grenadier Corporal Sam Kravinchuk read Asian history in Hong Kong libraries, while Corporal Lionel Speller attended nightly prayer meetings run by the Plymouth Brethren at the Duddell Street Gospel Hall. Private Barron was surprised to see people pulling cement mixers by hand and shocked to see people defecating in the street.

Meanwhile, Maltby struggled to keep his men focused and battled the British hierarchy’s complacency. When he wanted to mobilize the 2,000 men of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, an executive of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank said, “Don’t be ridiculous. Most of our male employees are Volunteers. The bank would have to close. There is no war, sir, and there never will be. The Japanese have more sense than to attack a British colony.”

An irritated Maltby retorted, “If my guess is right, it will be a long time before any bank in Hong Kong opens again.”

Still, Maltby tried. With his senior officers, he tramped the length of the colony, studying geography, inspecting defenses, siting positions.

On Saturday, December 6, the Royal Scots band performed at the Happy Valley Racetrack. While betters checked racing forms and big shots drank whiskeys and soda, military policemen went through the crowds, advising troops to return to barracks immediately. At the Royal Navy’s home away from home, the China Fleet Club, sailors hoisted beer and played Tombola.

Sunday, December 7, began with a church parade at the Church of England Cathedral near Victoria Barracks, the Fortress Headquarters in the city center. The Royal Scots bagpipes and Middlesex band led the men out of their colonial-era barracks to the services. Catholic, Muslim, Jewish, and atheist Tommies attended services rather than spend the morning peeling spuds. Maj. Gen. Maltby read from the Book of Matthew.

While British troops sang “Praise my Soul, the King of Heaven,” Sakai’s 60,000 attackers moved into position. A patrol of Punjabis on the frontier spotted the Japanese and reported it up the chain of command to Maltby in his pew. The service had not even reached the Prayers for Peace. “The Punjabis say there are at least 20,000 soldiers in the area, perhaps even more,” an aide told Maltby.

“They must be exaggerating,” Maltby said. “Our intelligence people are certain there are only 5,000 at the most.”

But Maltby summoned his senior officers outside individually and told them to alert the whole garrison. By 5 pm every one of Hong Kong’s 14,000 defenders—8,919 Britons and Canadians, 4,402 Indians, and 660 Chinese—was at his post.

Maltby’s plan divided his six battalions into two ad hoc brigades. The Mainland Brigade under Brigadier Cedric Wallis comprised the Royal Scots, the Rajputs, and the Punjabis, whose job was to hold the Gindrinkers Line as long as possible. The Royal Scots occupied the main position atop Golden Hill at the Shing Mun Redoubt. Lawson’s Island Brigade comprised the two Canadian battalions and the 1st Middlesex. Their job was to fend off a seaborne invasion of Hong Kong Island. Lawson set up his headquarters at Wong Nei Chong Gap in the center of the island, the only road connecting its north and south sides. The Volunteers were divided between the two commands to carry out demolitions and guard against sabotage. Maltby ordered his senior officers to spend the night at headquarters at Victoria Barracks’ Flagstaff House, the Kiplingesque headquarters in central Hong Kong.

At the Peninsula Hotel, night clerk Harold Bateson talked with a Swiss businessman, puzzling out two mysteries: the two Japanese cleaning girls who normally worked the late shift at the Peninsula had called in sick, and the Japanese-owned Matsubara Hotel was closed.

The answer came at 4:45 am on Monday, December 8, when Major Charles Boxer, the senior intelligence staff officer, relieved Royal Marine Major “Monkey” Giles as duty officer. Boxer, who spoke fluent Japanese and even lectured on Japanese history, turned the radio set to Tokyo’s frequency and heard the announcer break in to the program to read an Imperial Rescript: Japan had declared war on the United States and the British Empire. Boxer woke Giles, saying, “Get up, there’s a war on!”

“I know,” Giles answered. “With a chap called Hitler. Shocking type.”

“We’re at war with Japan,” Boxer said. Giles shot upright and answered, “It’s out of the question. I’m playing golf this afternoon. Anyhow, I haven’t got a tin hat.”

Giles immediately phoned Maltby’s aide, Lieutenant Iain MacGregor, to spread the word. MacGregor was junior partner in the family’s wine and spirits trading firm, and thus knowledgeable about Hong Kong’s social world—critical for a peacetime aide-de-camp—but no fool. He started hammering on doors throughout Flagstaff House, to alert the top brass.

Soon everybody got the word. Captain Christopher Man, who commanded 1st Middlesex’s Z Company—an ad hoc outfit of cooks, bandsmen, buglers, drummers, drivers, and mess waiters—was lying in bed with his wife of six months, Topsy Marr. Man’s reaction was to jump out of bed and into his clothes. With his orderly present, there was no time for a romantic good-bye, so he just said, “Put your tin hat on.” He didn’t see Topsy again for three years and eight months.

While hundreds of British, Canadian, and Indian troops yanked on khaki uniforms and ran to their stations, 48 Japanese bombers began Hong Kong’s portion of the war at 7:57 am, as a dark smear of Ida and Lily attack bombers roared over the New Territories. The Japanese swooped down on Kai Tak, defended by four machine guns, and blasted the airfield. The remaining bombers turned on Sham Shui Po Barracks. Most of the Canadian troops based there were gone, but Father F.J. Deloughery was giving morning Mass, and Sergeant Routledge and Signalman Fairley became the first two Canadian soldiers to be wounded by enemy action in the war.

The Japanese ground attack fell on Major George Gray’s C Company of 2/14th Punjabis on the border, who provided covering fire for Volunteer engineers, busily wiring bridges over the Sham Chun River. At 9 am, the bridges blew. Gray withdrew, and the Japanese began building replacement bridges. Chinese fifth columnists acted as guides, leading Japanese troops up mountain tracks and around obstacles.

Sakai’s men advanced through Hong Kong’s hills and villages, delayed by demolitions and British patrols. As the Japanese advanced, they looted and raped, as was their practice earlier during the Sino-Japanese War. Captain Khan Sherin of the Punjabis was astounded to see Japanese troops advancing toward his position, prodding Chinese civilians ahead of them as human shields. He asked Gray what to do, and the major said to open fire. “Will I also kill the women, major?” Sherin asked.

“It’s their bad luck. Now, get on with it.” Sherin’s men opened fire. After delaying the enemy, they continued to withdraw. At 6:30 pm, Royal Engineers blew up the railway tunnel south of Tai Po. The Punjabis dug in for ambush and saw the Japanese advancing in the bright moonlight. While the Punjabis machine-gunned the advance, 150 more Japanese landed behind them. Gray withdrew again. In all, the Punjabis covered 16 demolitions and killed more than a hundred Japanese that day.

The gunboat HMS Cicala was sent to Castle Peak Bay to use her 6-pounder guns to support troops ashore. Cicala came under repeated air attack by Japanese seaplanes, starting at 11 am. Her one-armed skipper, Lt. Cmdr. John Boldero, skillfully navigated the gunboat and avoided all the bombs. “It was a frightening, but at the same time, an intensely exhilarating experience,” he said.

The repeated bomb blasts left a shoal of dead fish floating around Cicala, and the cooks hauled them in. “Think yourself bloody lucky them Japs come over,” Able Seaman Wilkinson told his shipmates. “If they hadn’t, we’d be eating tinned stew and beans.” Nonetheless, Cicala found no surface targets that day.

On Hong Kong Island, an emergency hospital was set up at Happy Valley Racetrack to care for victims of the morning’s bombings. It faced bizarre shortages. Canadian nurse Kay Christie had to boil tongue depressers and re-use them.

Chinese fifth columnists and bandits sniped at passing British vehicles. Another sniper put a bullet through the windshield of a 1936 Ford truck delivering supplies in urban Victoria, narrowly missing Corporal Ed Bergen’s head. His frightened Chinese driver floored the accelerator, and the truck roared through the narrow street at 50 miles an hour.

By dawn on Tuesday, December 9, the British were dug in on the Gindrinkers Line, while Sakai’s men were advancing on it, delayed by British demolitions.

The Japanese also kept attacking Cicala, to no avail. The gunboat spotted a Japanese bus and truck near Brother’s Point and set them ablaze. Japanese bombs also rained down on the drydocked Tern, whose crewmen broke out the gunboat’s Lewis guns to answer the attackers.

On the night of December 9, Shing Mun was held by No. 8 Platoon of the Royal Scots under Lieutenant “Potato” Thompson, its men all weakened from malaria. That afternoon, Colonel Teihichi Doi, commanding the 228th Regiment, surveyed the valley with his field glasses and figured it was lightly defended. His orders were to pressure the British by night to wear them down and attack at dawn. He was short of artillery and his men were tired from long marches.

Doi sent his 3rd Battalion up the hill in rubber-soled shoes, through the rain, in single file. At 11 pm, the 3rd Battalion went in from the northeast, using satchel charges to blast holes in ventilating shafts. The Japanese charged into the tunnels and sealed off the northernmost pillboxes. Hand-to-hand fighting raged in the trenches and tunnels. The Scots shot up 3rd Battalion’s HQ with machine-gun fire, but it wasn’t enough. The Japanese overwhelmed the scattered pillboxes and hurled grenades down ventilation shafts. Then they surrounded the command post and silenced its defenders with more grenades.

With the exception of Pillbox 402, which held out for 11 hours before a British shell caved it in with a direct hit, Shing Mun Redoubt was cleared by 3:30 am. Lt. Col. Gerald Kidd, commanding the Punjabis, asked Wallis for permission to counterattack. “We’ve got to get that hill back! It gives the Japs command of the whole valley!”

“Forget it,” Wallis answered. “If you send your men up there, it will only weaken the Gindrinkers Line somewhere else. We can’t afford to lose another key position.”

Doi’s men, victorious, charged after the Indians behind the Scots and raised the Rising Sun over Shing Mun. When Doi saw the flag go up, he radioed Sakai to announce his victory. Incredibly, Sakai was angry. Doi’s regiment had crossed into the 230th Regiment’s zone of operations and disobeyed orders to attack at dawn, and in the tradition-bound Japanese army, disobedience was a major offense. More importantly, Sakai was afraid that other officers might launch half-cocked attacks with disastrous results.

Doi, however, refused to retreat. Soon the two officers were swapping angry messages back and forth, and court-martial threats were being exchanged before dawn. Finally, Sakai agreed to let Doi stay on the hill provided that no other officer launched an attack without express permission.

Meanwhile, the British struggled to react. Maltby sent his reserve, Winnipeg Grenadiers Company D, across to Kowloon by Star Ferry to cover evacuation if necessary. Company D hiked up to a road junction three miles south of Shing Mun and started digging trenches; they were the first Canadian ground troops to see combat in the war.

On the 10th, the Japanese continued to jab at the Gindrinkers Line. They sent two sampans full of troops in Chinese dress to attack Tide Cove, and the sampans were machine-gunned. When the 228th Regiment attacked the 5/7th Rajputs, Captain Bob Newton’s company held out. Newton told his men, “Now then, who’s going to win the Victoria Cross? Stand fast and shoot straight. There will be much killing to be done soon.”

The Japanese hit Newton’s men with a frontal assault, believing the Indians to be no better soldiers than the Royal Scots. But Newton’s men, backed by the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery, gunned down the attackers and sent them fleeing.

Having defeated the Japanese, the defenders made rude jokes about the Royal Scots’ poor performance, with tales of frightened Scots loaded with ammo fleeing all the way to brigade headquarters. It was a sorry page for the British Army’s oldest regiment, with the “First of Foot” being known as the “Fleet of Foot” in the battle. The fact that the outfit had a hundred men in the hospital with malaria and most of its others were untrained recruits made no impact. Major Stamford Burn, the second-in-command, was so upset by the stories that he shot himself.

Also having trouble with the heavy barrage of Japanese bombs and shells were the Canadian battalions, most of whom were squatting in pillboxes and trenches on Hong Kong Island. It was their first exposure to war. Royal Rifleman Sidney Skelton wrote in his diary, “Two of our boys have gone crazy in the head. The bombing has snapped their minds.”

At sunset, the Royal Scots were ordered to withdraw to a position in front of Golden Hill. The Scots struggled up the hill, loaded with equipment, weakened by malaria, to “prepared positions,” finding them to be three-year-old weapons pits surrounded by rusted barbed wire. Cold, hungry, and disgusted, the Royal Scots dug in to await the enemy’s night attack.

The 230th Regiment advanced on Golden Hill fully camouflaged. A Royal Scot said, “You couldn’t see a Jap until he was on the end of your bayonet.” The Japanese gave the Royal Scots sniper fire, mortar rounds, and colorful invective to keep them jumpy. Doi’s plan was to break through the Royal Scots and cut off the two clearly tougher Indian battalions.

At dawn on the 11th, the 230th Regiment assaulted the Royal Scots’ position supported by heavy mortar fire. Bayonets fixed, the Japanese swarmed all over the Royal Scots in waves. They killed more than 60 men. C Company was cut from 35 to 10 men.

The Royal Scots fought hard, determined to regain their reputation, killing hundreds of Japanese. Wallis told the Royal Scots’ commanding officer, Lt. Col. Simon “Scram” White, that the battalion’s good name was at stake. A counterattack was an absolute necessity. White’s men could not comply. He pleaded with Wallis to cancel the order, and Wallis agreed.

But the order to cancel did not reach Captain David Pinkerton and D Company, the Royal Scots’ reserve, which had not yet been engaged. He told his men, “We’re going to get those bastards. Golden Hill belongs to us.” The Japanese had more men and weapons, but Pinkerton’s company stormed to the top. Pinkerton personally led the assault, hurling grenades, firing his revolver, and shouting insults at the Japanese. He survived a mortar explosion, a bayonet lunge, and a bullet that grazed his temple. A soldier tied part of his shirt around Pinkerton’s head to stop the bleeding, and the company regained Golden Hill. Pinkerton was awarded the Military Cross.

When Sakai heard of the rout, he told his officers that the price of defeat by an inferior enemy was hara-kiri, but the reward for victory was eternal glory. The officers got the message. The Japanese launched another fanatical charge on Golden Hill, and this was too much for Pinkerton’s band. At 10 am, the Japanese had Golden Hill.

The Japanese could now swing in from behind the Rajputs and the Punjabis and destroy them in detail. At noon, Maltby ordered withdrawal from the mainland. “The evacuation order was given on regrettably short notice but was unavoidable owing to the rapidity with which the situation deteriorated,” Maltby wrote in his official dispatch.

The Rajputs and Punjabis would withdraw east to Devil’s Peak Peninsula, where HMS Thracian would cover their evacuation. All other units would fall back to Kowloon, where Star ferries and every available launch would be ready.

Brigadier Wallis told all this to a lieutenant commanding a unit of 50 Indians. “The lieutenant looked excited and had a strange look in his eyes,” the brigade diarist wrote. “He spoke somewhat incoherently and said, ‘Are you sure this is necessary?’ The Brigade Commander noticed the lieutenant’s hand creep to his revolver. From the look in his eyes Wallis realized this young officer was about to shoot him. He rushed the lieutenant who was drawing his pistol, knocked it from his grip, and ordered him to hospital.”

With the withdrawal ordered, the Royal Engineers and Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps set demolitions and blew up the cement works, the China Power and Light Station, the railway terminal, the Kowloon docks, and all remaining British merchant ships, including a Swedish vessel. At HMS Tamar, Chinese crewmen from HMS Cicala deserted, so the crew and guns from the drydocked HMS Moth were removed for Cicala. The drydock was flooded, and HMS Moth was scuttled. Also cut—the Eastern Telegraph Cable Company’s links to the outside world. Tamar herself was also scuttled.

At the ferry terminals, panic reigned. British officials and Hong Kong police struggled to issue channel-crossing permits to mobs of frenzied Chinese. White residents of Kowloon shoved fistfuls of money at sampan owners to float them across to the island. The roar of explosions added to the din and fear.

Meanwhile, the infantrymen withdrew. The Royal Scots and D Company of the Winnipeg Grenadiers fell back on Sham Shui Po. When the men formed up, buses took them to the ferry pier, where launches and Star ferries waited. “We looked across the water, usually ablaze with the lights of the island,” wrote a Royal Scots officer. “That night there was nothing but darkness ahead.” By 10:30 pm, the Royal Scots were back in Victoria Barracks. Three hours later, D Company reached the Star ferry terminal, finding no ferries.

Captain Allan Bowman, commanding D Company, phoned Captain Wilfred Queen-Hughes on the opposite bank to report stationary ferries in Victoria. Queen-Hughes stomped up to a ferryboat and ordered the Chinese captain to make the crossing. He refused. Queen-Hughes shoved his pistol in the captain’s face, and the ferryman cranked up his engine. A few minutes later, D Company shoved its way onto the ferryboat, along with hundreds of fleeing Chinese—including a funeral cortege with a black hearse.

All night long, the ferries ran back and forth between Victoria and Kowloon. At the Victoria docks, the Chinese launch crews deserted, and many boats were damaged by shells. British and Canadian troops worked with civilian volunteers to man the gaggle of launches. Among them was a Canadian who claimed to be the Class A dinghy champion of Montreal.

The Indian battalions, exhausted from the fighting, hauled their gear over mountain tracks. Some of their mules, laden with food and water, took fright and ran off.

The Indian troops entered Kowloon a few minutes ahead of the Japanese. HMS Thracian, battle ensigns snapping and 4-inch guns blasting, oversaw the evacuation. Indian troops rowed, waded, or swam out, clutching their rifles. Thracian Petty Officer Peter Paul was awed by the Rajputs’ discipline in the face of disaster.

When the Punjabis reached the ferry, they refused to leave until the last civilians had been withdrawn. They set up a rear guard under Lieutenant Nigel Forsyth to hold the enemy off until the last ferry. Forsyth himself was the last man off, jumping into the boat’s stern. With his Indian gunners, he kept up rapid fire on the advancing Japanese, some of whom even tried to jump into the ferry from quayside. They missed their footing, and Forsyth’s men machine-gunned them as they fell into the water.

The British withdrawal left anarchy behind. Looters attacked ruined and blasted shops, even taking wooden shelves, doors, window frames, and floorboards to use as firewood now that the gas mains were gone. British homes were stripped bare. Chinese fifth columnists put sand in rice and kerosene in fire buckets.

At 9:20 am on the 13th, HMS Thracian took off the last Rajputs. Two Indian soldiers were cut down by Japanese rifles as they raced toward the destroyer. Thracian sailed for the back-up base at Aberdeen, where Maltby himself congratulated the Rajputs in Hindustani.

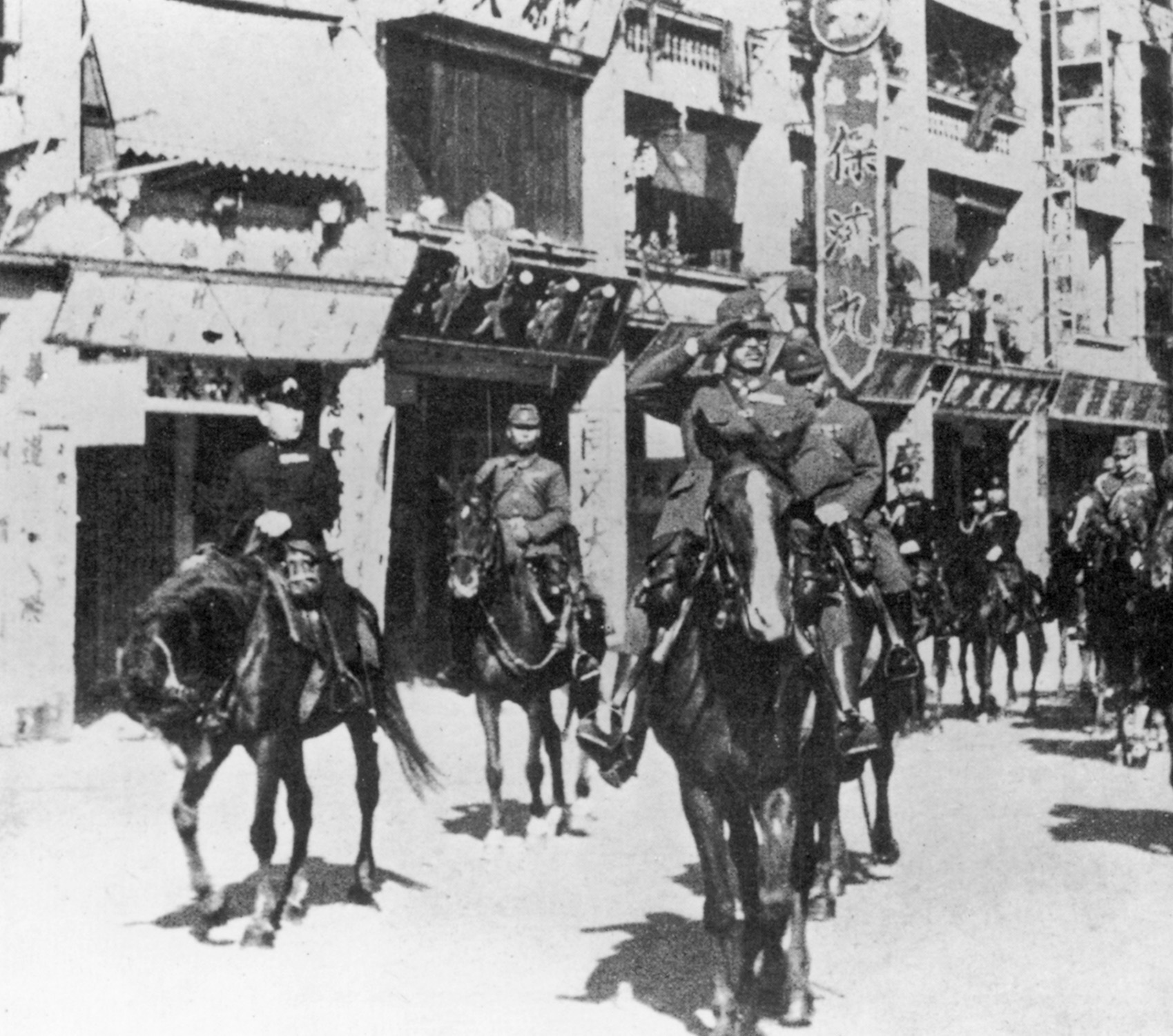

Another general was using strong language that morning—Sakai. He was having all kinds of troubles: badly cooked prawns had given him a migraine headache. The white horse rounded up for the victory parade was gray and flea-bitten, and his orderly had not properly polished his samurai sword.

More importantly, his invasion of Hong Kong was not moving as quickly as planned. British battalions that were supposed to be destroyed were slipping away in the dark. Casualty lists were frightful. However, the British were on the run. One good psychological shove might be enough to convince the weak Westerners to surrender.

At 9 am, Sakai sent a launch with three officers, an interpreter, and two female hostages under a white flag and a white banner that read “Peace Mission” on the bow.

British troops cordoned off the Victoria Pier with bayonets, and senior officers came to greet the emissaries, joined by Detroit News correspondent Gwen Dew. In a flurry of salutes and protocol, Colonel Tokuchi Tada presented Sakai’s letter to Major Boxer. “I have a letter for your governor [Sir Mark Young],” Tada said. “We wish you to surrender. I will wait for a reply.” Failure to surrender would unleash a massive artillery bombardment.

Boxer drove off with the letter while Tada unloaded his hostages. One was Mrs. MacDonald, Russian and pregnant, who was allowed to leave for the hospital. The other was Mrs. C.R. Lee, accompanied by her two dachshunds, Otto and Mitzi. The wife of Governor Young’s secretary, she was being kept to assure the truce boat’s safe passage. Mrs. Lee handed her dogs over to a British soldier. Captured the night before, Mrs. Lee had been ordered into the party.

Dew asked interpreter Othsu Dak what the terms of surrender were. “Equable terms for both sides and safe conduct for all,” he replied ambiguously.

Fifteen minutes later, Boxer returned with Young’s answer. It was one word: “No.”

Tada said, “It would be a pity if we have to level this beautiful city.” Then he stepped back, saluted, and returned with Mrs. Lee to his boat.

Sakai was more impressed. “I am amazed the governor has so much courage,” he wrote in his diary. Then he ordered a merciless two-day bombardment.

Maltby reorganized his defenses. The Mainland and Island Brigades became the East and West Brigades. The Royal Rifles and Rajputs were placed in East Brigade under Wallis, with the Winnipeg Grenadiers and Punjabis into the West. Lawson was annoyed—both he and the Canadian official historian years later viewed splitting up the Canadians as a mistake—but he set up Brigade HQ at the Wong Nei Chong Gap, the notch in Hong Kong’s hills that enabled the main road to go from Victoria to Aberdeen. The Middlesex men still held their pillboxes under Fortress Command. Five batteries and seven rifle companies of Volunteers were the reserve. The East Brigade set up shop in the Tytam Gap, on the road from Sai Wan Hill to D’Aguilar Peak and Stanley.

The Japanese began their bombardment with a variety of heavy guns, 4-inchers and 9-inchers and 150mm and 75mm field pieces. Forced coolie labor carried the ammunition, and those who did not keep up the pace were shot.

Japanese shells rained down on Victoria and Wanchai, blasting apart buildings, starting fires. The north shore was covered with black smoke, and the firefighters were overwhelmed. Dead bodies and garbage lay heaped in the streets. Sanitation crews tried to burn the refuse and haul off the corpses. One shell blasted a 9.2-inch gun on Mt. Davis on the northwest shore. Another Japanese 9-inch shell entered the Fortress HQ plotting room but failed to explode. Sappers dislodged the shell to find it stamped clearly, “Woolwich Arsenal, 1908.”

Other shells landed amid the hospital set up at the Happy Valley Racetrack, though it was clearly marked with the Red Cross, killing and wounding doctors, medics, patients, and horses alike. Japanese guns also shredded mansions on The Peak, ripping up 50 years of British power with a few well-aimed shells.

Emily Hahn hid in the basement of the Selwyn-Clarke villa with her infant daughter Carola and other local residents, listening to shellfire and a BBC radio newscast voice saying, “The gallant fortress of Hong Kong is holding up well against the enemy assault.”

The BBC’s morale-boosting rhetoric was echoed in London by Fleet Street, whose newspapers spewed out stories saying Hong Kong was dug in to withstand a six-month siege and extolling Young’s defiance.

December 13 became December 14. Late in the day, HMS Thracian finished refueling at Aberdeen and sailed back into Kowloon Bay, hoping to make a hit-and-run raid on the Devil’s Peak. One mile short of her target, the old destroyer ran aground in the moonless night, hitting offshore rocks with a shuddering crash. They pierced her forward compartment. Lt. Cmdr. Pears, the skipper, backed out, but as he was about to head home for repairs, his lookouts saw two large motorized junks jammed with Japanese troops dead ahead. Thracian’s guns opened fire and exploded the first junk immediately; the second one sank minutes later. The battered destroyer steamed home. Next day, the Japanese answered Thracian’s impertinence by bombing her at Aberdeen, which required her to be drydocked.

Young grappled with hysteria, shelling, and food shortages. Many key Chinese workers had deserted gun emplacements and hospital jobs. Panicking refugees raided private kitchens, sometimes killing the occupants. Armed robbers worked through the air-raid shelter tunnels. Others robbed refugees sleeping on the streets and British civilians going in and out of government buildings. Even essential businesses closed down rather than face armed robbery.

Shells knocked out the electrical power and that in turn shut off air raid sirens. Hour-long queues for free rice were subject to bombing, shellfire, and random strafing. A Japanese shell fell on a long queue of people waiting for their rice issue, the shrapnel cutting them down where they stood.

Young imposed a 7:30 pm to 6:30 am curfew and ordered the police to round up suspected fifth columnists, and even asked the leading Chinese Triads—Hong Kong’s version of organized crime—to crack down on the youthful hoods causing chaos. The Triads were happy to do so. They saw the street gangs as upstarts threatening to take over their lucrative prostitution, opium, and gambling operations. Looters were shot.

That evening, 300 Japanese soldiers in rafts, sampans, a motorized junk, and inflatable rubber boats started crossing the Lye Mun Strait. The men sent over were not the 38th Division’s best: Sakai used his sad sacks, theorizing that if they could establish a beachhead, then the 7,500 men behind would roll over the British. Besides, it was a cheap and effective way to rid himself of the incompetents that plague any army.

The Japanese believed the Lye Mun barracks were deserted and the coast defenses devastated. They were wrong. The British had observed the preparations and reinforced the Royal Rifles and Rajput defenders with three platoons of Volunteers and two searchlights.

Soon the British heard the junk’s motor. The Volunteers flipped on the searchlights and caught the Japanese. The Volunteers’ 6-inch howitzers blasted the junk, while the Rajputs and Canadians opened up with Bren gun and rifle fire, massacring the enemy. Japanese soldiers tumbled out of rafts and sampans and drowned. Japanese artillery knocked out one searchlight.

At 2:45 am, the Japanese tried again, and the surviving searchlight caught them once more. The Japanese again took a beating, but did not shell the searchlight. There was a bizarre reason for that.

Lieutenant Minoru Okada, a 32-year-old martial arts master who had written two novels on samurai heroes and was a 1936 Olympic athlete, was to lead four swimmers across the bay and destroy the searchlight at close range. Okada theorized that if the Japanese simply shelled the searchlights, the British would replace them. But if his team destroyed the searchlight up close, they could kill the crew, destroy the position, and the British would be too demoralized to replace the light.

The Japanese commander valued samurai spirit over military logic and gave Okada and his volunteers the go-ahead. Swimming in underwear through the straits with bundles of dry clothing, grenades, and explosives on their backs, the five made it to the island. There, they pulled on their Chinese coolie outfits and crawled through barbed wire, past a snoozing Volunteer in a truck.

At 4 am, Okada reached the searchlight, and his group hurled grenades over the sandbags at the target. They blew up everything but the searchlight. The defenders opened fire and killed one Japanese soldier. Okada and the rest ran back to the sea and swam back to the north side.

“The searchlight was of little significance,” Okada wrote in 1954. “What mattered was the deed. We showed that the enemy could not keep Japanese soldiers off the island. They were too fat, too decadent. Their destruction was inevitable.”

Sakai was less impressed by Okada’s bravado, but he reasoned that the British had to be short of ammunition and supplies. Furthermore, lantern signals from fifth columnists on the island were giving wildly inflated casualty counts for the British. One spy reported British losses as 1,500 dead and 2,000 wounded. Actually it was 55 dead, 95 wounded, and 65 missing.

Sakai figured one more surrender offer might do it. He decided to shell the British on Tuesday (December 16), demand surrender on Wednesday (December 17), and storm ashore with all three regiments on Thursday, December 18.

The bombardment went on. The defenders were very tired—at Bowen Street Hospital the medical staff had slept about seven hours in four days. The wards were overflowing. There was little cheer elsewhere, the pillboxes being methodically destroyed and now even water was short. Young rationed water, opening the mains from 6 am to 9 am and 3:30 pm to 6:30 pm daily. Civil defense workers and firefighters scoured Hong Kong Island to find wells.

Next, Young banned sales of petrol to private car owners, requisitioned all buses, and shut down the 40-year-old streetcars, which had been grinding along Queen’s Road from sunup to sundown since the war started. Even rickshaw drivers abandoned their jobs. With the gasoline shortage, garbage drivers could not go out, and people dumped their refuse openly. Also deadlined were trucks that picked up excrement from public lavatories, which created health hazards.

Yet life went on. A Chinese tailor hiked up the Peak to deliver a suit. A civil servant bawled out his secretary for arriving to work 20 minutes late. The British-American Tobacco Company presented 1st Middlesex’s C Company with 25,000 cigarettes, which prompted one soldier to say, “As long as they’ve got their fags, they’ll hold the bloody Island for years.”

At 11 am on Wednesday morning, Sakai and his naval counterpart, Vice Adm. Masaichi Nimii, sent another “Peace Mission” boat to Victoria. Colonel Tada, in his dress uniform, and interpreter Othsu Dak, in his black suit, led the four-man party. No hostages this time, and both got directly to the point: Sakai wanted a British surrender by 4 pm. There would be a cease-fire until then.

Once again Boxer took the letter. He told Tada to return at 2:30. At that time, everyone reassembled to read Young’s response. Boxer read sonorously, “The Governor and Commander-in-Chief, Hong Kong, declines most absolutely to enter into any negotiations for the surrender of Hong Kong and he takes this opportunity of saying he is not prepared to receive any further communications on this subject.”

The Japanese were stunned. Sakai could not believe the British were such masochists. He was supposed to have led the victory parade on December 17; now he would lose face in Tokyo. Japanese generals who failed were not expected to outlive their failures. Fortunately, Tokyo showed sense. Since the British were fighting on, Sakai’s deadline was extended until New Year’s Day. The 38th Division’s role in the invasion of Java was pushed back until February.

Maltby was also cheered. He believed two Japanese surrender demands in four days meant the Japanese were afraid of attacking the island, were suffering pressure in their rear from the Chinese, and were reluctant to attack. His belief was echoed in the British and Canadian press.

“Young’s reply to the Japanese should be read in every public place and school throughout the Empire,” gushed The Times of London. “Hong Kong, braced and exhilarated by the roar of her great guns, tersely rejected a second Japanese request to discuss surrender terms,” said the Daily Mail. The Canadian press talked up a Chinese breakthrough, reporting savage attacks. Actually, they were guerrilla raids. Chiang Kai-shek’s forces were not attacking anyone.

Sakai, however, had had enough. H-hour would be 10 pm on December 18. Shoji’s 230th Regiment would embark from a point north of Kai Tak and land 400 yards east of North Point. Doi’s 228th Regiment would embark from east of Kai Tak and land in the center at Braemar. Tanaka’s 229th Regiment would embark from Devil’s Peak and land at Sau Ki Wan. Each regiment would attack in two waves: the first in 14-man collapsible rowing assault boats, the second and the rest in powered landing boats. Each regiment would send in two battalions, leaving three battalions in reserve. The bridging engineers were to provide the landing craft.

With one hour to get the first wave across, speed and surprise were essential. Once ashore, the Japanese would grab Mount Nicholson, Wong Nei Chong Gap, Jardine’s Lookout, Mount Butler, and Mount Parker.

On Thursday, December 18, the skies opened, drenching both sides with rain. Rain, fog, and smoke from the burning Anglo-Persian oil refinery and paint factory cut visibility on the north shore to nil. The Japanese battered the waterfront defenses with shellfire, closing down the main road from Causeway Bay to Shau Ki Wan. Blasted trolleys, wrecked trucks, and shredded and live power cables made movement impossible.

The ceaseless shelling was having its impact on the defenders. “This day has been the worst yet. Our position has become a living hell,” wrote Sydney Skelton. “My nerves are on edge. I could eat a horse. Shell landed 30 feet from where I was standing. One fellow got shrapnel in the side. My head swam and my nerves seem to be all gone. More lads were wounded again today. The sky is as red as blood.” Some Canadians had not had a hot meal for 24 hours. Father DeLoughery, the chaplain, visited the men by day and hospitals by night, offering Holy Communion and comfort.

As 2nd Battalion/228th clambered into its assault craft, Skelton wrote, “Huge fires are raging in Victoria. The bombardment is still on. This is one day I shall never forget. Tomorrow will tell another story.”

At 7 pm, 3,500 Japanese troops moved out in junks, sampans, rubber boats, and anything that could float. Another 4,000 Japanese troops waited to go over in the second wave.

The defense opened up with machine-gun and artillery fire, which broke up the Japanese attack order and flipped boats in the air and their human cargo overboard. Oars broke and men rowed with rifles and entrenching shovels through smoke, haze, and rain.

When the 228th reached their beaches, company and platoon leaders were cut down by British fire. The Japanese reacted in samurai tradition: They fixed bayonets and charged the enemy. As soon as the first wave landed, the second wave moved across. They hit the beach and were pinned down.

Shoji’s and Tanaka’s regiments fared little better. Shoji captured British pillboxes but was soon pinned down by artillery. Tanaka, under Rajput machine-gun fire, told his men to take no prisoners.

Tanaka’s men also stormed Sai Wan Hill, held by the Volunteers’ 5th AA Battery. The 29 defenders were surrounded and outnumbered. A Japanese officer shouted in English, “Surrender and we will save you! Come out all men, and you will be released.”

The British, Chinese, Eurasian, and Portuguese defenders came out, hands up, one at a time. The nearest Japanese soldier bayoneted the first man … then the next man … and the next. One Volunteer who saw what was happening tried to run and was cut down by rifle fire. The rest of the men were tied up and held for two hours in a small room. Then they were led out, flung on the ground, and used for bayonet practice. The Japanese hurled the dead and dying into a nearby pit. Only two survived— gunner Chan Yam-kwong and bombardier Martin Tso Hin-Chi—by hiding among the rotting bodies for three days, before escaping when a Japanese guard turned his back.

There was horror at Captain Martin Banfill’s first-aid post at the Salesian Mission in Shau Ki Wan, too, when Tanaka’s men stormed up. A Japanese patrol kicked in the front door and rounded up the 25-member staff. The women were not harmed, but a Japanese officer ordered the men to hand over their watches, rings, and wallets to the invaders. Then the men were marched 200 yards down the highway, where Banfill, as the CO, had his hands tied and a rope around his neck.

“We are medical personnel,” Banfill said, “Noncombatants.”

“Soldiers first, medical second,” retorted the Japanese officer, a Lieutenant Honda. “We have instructions from our commander-in-chief. You must die.” They shot five doctors, sparing Banfill. “I will kill you later. First you are to be questioned,” Honda said. He took Banfill away, while his troops bayoneted and beheaded the remaining medics. Incredibly, Corporal Norman Leath of the Royal Army Medical Corps and Dr. Osler Thomas survived the bayonets, living to give testimony that sent Tanaka to the scaffold. Leath, in pain from his wounds, survived for eight days, walking across Hong Kong’s hills and drinking muddy water from streams, before stumbling into an internment camp.

Meanwhile, Honda took Banfill over the hills to a Japanese encampment. En route they spotted a wounded Rajput lieutenant and bayoneted him. At the camp, a senior officer interrogated Banfill and found out he knew nothing about the defenses. The doctor wound up in a POW camp.

Chinese fifth columnists grabbed Fort Sai Wan and started spraying the Royal Rifles’ encampment with captured Lewis machine guns. Major W.A. Bishop called Fortress Headquarters to ask them to fire artillery on the fort, and they refused. “We have it down on paper that friendly troops occupy the fort. We cannot shell it.”

“Well, they sure as blazes aren’t acting in a friendly manner,” retorted Bishop. Meanwhile, Japanese troops entered the Lye Mun barracks, meeting up with the Royal Rifles. Bishop grabbed a Tommy gun and went off with another officer to find out what was going on. He bumped into a Japanese patrol. Bishop cut loose with his Thompson, killing seven Japanese and earning a Distinguished Service Order.

All along the north shore the Japanese invasion stormed. Tanaka’s men, between beheadings, clambered up Mount Parker and Mount Butler. Captain Bob Newton’s D Company of Rajputs, down to a hundred men, faced Shoji’s regiment with valor and determination. The Rajputs had enjoyed only one night’s sleep since the battle began. Worse, fifth columnists had cut the Rajputs’ barbed wire. Nonetheless, the Rajputs gave the Japanese a warm greeting with mortar and machine-gun fire and then launched a bayonet charge in the smoke and rain. But the Japanese rolled grenades down ventilation shafts into pillboxes. Newton himself was cut down by enemy fire while shouting encouragement to his men. When Newton’s body was found, his revolver was empty, and he was surrounded by six dead enemy soldiers.

Once Newton died, the Rajputs began to waver and had to withdraw at 2:30 am. The slaughtered company numbered only 35 men and was ordered to join Company B at Leighton Hill, northeast of Happy Valley Racetrack.

Shoji’s regiment climbed up the hills, heading for the summit of Jardine’s Lookout, two miles from their beach, which overlooked the Wong Nei Chong Gap. By 3:30 am, Shoji himself had caught up with his 3rd Battalion on the Lookout’s northeast slopes, which were held by two platoons of Volunteers.

Another roadblock to Shoji’s advance was the power station at North Point, held by the Hughes Group, under Lt. Col. H. Owen Hughes, in peacetime the chairman of the Union Insurance Company of Canton.

The Hughes Group was composed of men too old to qualify for normal service, all 55 and over. What they lacked in youth they more than made up for in morale, enthusiasm, and weapons accuracy. A total of 72 “Hughesiliers” were assigned to hold the Power Station against saboteurs, under Major The Honorable J.J. Paterson, a colorful legislator and social lion who held a private box at Happy Valley. He was also a veteran of the African Camel Corps in 1917. The defenders included T.A. Pearce, the 67-year-old secretary of the Royal Hong Kong Jockey Club; Private Sir Richard Des Voeux, secretary of the powerful Hong Kong Club; “Pop” Hingston, head chef of the Hong Kong Hotel; and the jaunty, aristocratic Free French Captain Jacques Egal, who had been wounded and captured in World War I. Hingston had fought with the Canadians at Vimy Ridge.

The Hughesiliers were reinforced by a platoon of Middlesex men and 30 British technicians from the Hong Kong Electric Company. At 1:45, the power station and its motley defenders were surrounded. Paterson told his men, “By rights, half of you ought to be dead now. If a man can’t stay in his position alive, he’ll stay in it dead. Those are your orders; now give ’em hell.”

The exhortation worked. The slow-moving and myopic defenders of the Power Station held off repeated bayonet charges by the Japanese, who had a 20:1 manpower advantage. At dawn, the Hughesiliers gaped at masses of sprawled Japanese bodies lying around them, and the enemy was gone. It reminded R.G. Burch of the Boer War: “The Boers had a nasty trick. They’d pretend they were gone and then come at you with everything they had. These chaps could be doing the same thing.”

Des Voeux answered, “It’s quite possible, all right. But I’ll tell you one thing. I’d sooner die here fighting than rot in a lousy prison camp. Anyway I’m threescore and 10 and living on borrowed time now.”

Sure enough, the Japanese launched a mortar barrage five minutes later, smashing the concrete walls, killing Des Voeux. The Japanese charged through the barrage and smoke, tossing grenades through windows and holes. Tam Pearce, seeing that the building was on fire, pointed at a wrecked double-decker bus nearby, and said to Paterson, “If it’s all right with you, I’d prefer dying there than being roasted alive.”

Paterson said, “My dear fellow, there’s a great deal to what you say.”

Pearce and five Hughesiliers took up position in the bus and held it for two hours against bayonet charges. Finally, the Japanese brought up three machine guns and shredded the defenders, killing everyone but Private C.E. Geoghan, who drove off an enemy attack singlehanded, killing an officer and four men with five rounds before the Japanese shot him, ending “The Battle of the Bus.”

In the power station, Paterson and his crew hung on. Unbelievably, the last 12 ancient warriors fought on until 4 pm, when they ran out of ammunition and surrendered. The Japanese roped up the old men and marched them off. “The delay the force imposed was very valuable to me,” Maltby wrote later in his report.

As the Japanese advanced, the war came closer to Hong Kong’s Central District. Wounded Chinese civilians filled the Jockey Club, which had been converted into a hospital. Bowen Road Hospital took 111 hits during the siege. Wounded victims were wheeled in assembly-line fashion into surgery, where doctors worked for 36 hours straight.

With most Royal Navy ships out of action, there were a lot of sailors without jobs. They were organized into 30-man combat groups, issued rifles and tin hats, and sent to fight as infantry. Royal Marine Major “Monkey” Giles was given command of sailors from the naval base, one of whom was a clerk whose rifle was filled with dirt. “You’ll have to clean that before you start fighting,” Giles said.

“Yes, sir. Please, sir, how?” the clerk answered.

Meanwhile, as December 19 advanced, so did the Japanese on Wong Nei Chong Gap and its police station at the gap’s summit. Corporal Sam Kravinchuk and the Winnipeg Grenadiers’ A Company, under Major A.B. “Granny” Gresham, were sent to take and hold Mount Butler and the Tai Tam Reservoir. Drenched from pouring rain, the Grenadiers occupied the high ground. At dawn, the Japanese attacked. Kravinchuk and his company fixed bayonets and drove the Japanese back. A sniper killed Gresham. The company held on, as Company Sgt. Maj. John Osborn personally killed six Japanese with his bayonet and tossed live enemy grenades back at the Japanese. Volunteer Corporal M.S. Lau and three men held on until 7:30 am when all but Lau were killed.

But the Grenadiers had to retreat. During the withdrawal, Kravinchuk had to escort two wounded pals to a first-aid post in a pillbox. When the three Canadians reached it, Kravinchuk rapped on the door, saying, “Hello, anybody home?” The door flipped open, and two Japanese soldiers shoved bayonets at him. The Japanese prodded the three Canadians across the clearing to a shack full of other Canadian and British prisoners.

By dawn on Friday, December 19, the Japanese were nearly halfway across the five-mile Hong Kong Island. Their objective was the island’s reservoirs in the center. That would cut the defenders in two and cut off their water supply. The Rajputs were nearly obliterated, and Japanese forces were on the move. Victory seemed near.

Lawson probably agreed. He burned his code books and radioed Ottawa: “Situation very grave. Deep penetration made by enemy.” Maltby, however, said, “Japanese will undoubtedly try to ferry more men over tonight and continue infiltration, but I hope to be in a position to launch a general counter-attack tomorrow morning.”

Maltby, seeing that East Brigade was down to the Royal Rifles, two companies of Volunteers, and some Middlesex machine guns, ordered it to withdraw to the south coast, holding Stanley Fort. There it would regroup and counterattack, backed by the fort’s mobile guns. Lawson’s West Brigade would withdraw from Wong Nei Chong Gap.

Maltby gave the message to Corporal Lionel Speller, who fired up his BSA 500 motorcycle for the five-mile trip. Speller had been on the go all morning. His previous “vital mission” was to deliver a package of dog food to a British colonel in a pillbox. Speller, a keen motocross driver, struggled through sniper fire to reach Lawson’s Tac HQ by 8 am, earning a Military Medal for his valor. At 9 am, he went back to Fortress Headquarters.

At 10 am, the Japanese attacked Lawson’s HQ, surrounding it. Two truckloads of beached sailors from the now grounded HMS Thracian under Lt. Cmdr. Pears were rushed up, but were caught in an ambush. Most of the Thracian sailors were cut down as they jumped out of their trucks. Petty Officer Peter Paul rolled down the slope and hooked up with some Royal Scots eight hours later. Four sailors held out in a house against Japanese fire for two hours. When their ammo was gone, they waved a white handkerchief. The Japanese took them out and bayoneted three of them. The fourth, Able Seaman Ronald Mattieson, yanked the rifle out of a Japanese soldier’s hands and dived head-first over a cliff. He fell 50 feet, broke his collarbone, and landed next to a cave, which he hid in for the next 30 days.

Under heavy machine-gun fire in his pillbox, Lawson phoned Maltby to say, “They’re all around us. I’m going outside to fight it out.” Lawson and his staff officers ran out of the pillbox, and Sergeant Bob Manchester saw Japanese machine guns cut them all down. When Shoji heard that a British brigadier was among the bodies at Wong Nei Chong, he ordered the body wrapped in a blanket and temporarily buried “on the battleground on which he had died so heroically.”

Captain Allan Bowman died rushing a Japanese patrol, firing his Thompson. Captain Bob Phillips, an eye knocked out, fought on until his ammo ran out. Lieutenant Len Corrigan saw a Japanese officer advancing brandishing his samurai sword, wrestled him to the ground, and strangled him to death.

Up on Mount Butler, Osborn led 35 men of A Company of the Grenadiers down from the heights, with hundreds of Japanese in pursuit. A career soldier, father of five, and devoted family man, Osborn was cool and efficient. His platoon struggled down a slope into a ravine, seemingly having avoided the Japanese. Suddenly a Japanese soldier tossed a grenade into the group that landed three feet from Osborn. The sergeant major yelled “Clear out!” and flung himself on the grenade, absorbing the full blast.

The platoon, stunned by Osborn’s self-sacrifice, ran on. Private Stanley Baty tripped and fell on his face—which saved his life. When he hit the ground, Japanese rifles and automatic weapons opened fire, killing everyone near Baty. He and 14 survivors broke out their rifles and Bren guns and shot back. After 20 minutes, the Grenadiers decided to surrender. One of them waved a white handkerchief. He was shot down. “We’ve had it boys,” Baty said. “Those buggers are aching to do us in.”

They fought on as long as the ammo lasted—10 more minutes—and then ripped out their rifle breeches. Then they all stood up, expecting to be shot. The Japanese rose, bayonets pointed. An officer pointed a sword at a man near Baty. Two soldiers grabbed the Canadian, hauled him off, and bayoneted him to death. The message: Everyone else would suffer the same fate unless they did what they were told. The Japanese stripped the Canadians of their rings, watches, and wallets and marched them north.

By dusk, Baty and his pals were jammed in a one-room building packed with British, Canadian, and Indian POWs. There was no food, water, or sleep. They endured “The Black Hole of Hong Kong” for 20 hours.

Osborn’s body was never identified. His name was chiseled on the memorial to the missing at Sai Wan. When the Canadian government learned of his deed after the war, he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross—the only one of the battle.

The Royal Navy was in action, too. MTB-7 and MTB-9 were ordered to sail into Hong Kong Harbor at 8 am and shoot up enemy vessels with machine guns and grenades. Lieutenant R.W. Ashby, skipper of MTB-7, laconically reported, “I opened fire on the enemy landing craft with all my guns at 100 yards range with excellent results, and passed down the leading string at a distance of about five yards, firing continuously. I dropped two depth-charges which failed to explode. I then came under machine-gun, howitzer, and light artillery fire from both shores and also from cannon and machine-gun fire from aircraft. The boat was hit several times and a cannon shell exploded in the engine room putting my starboard engine out of action and killing my Leading Stoker … my speed was reduced to 22 knots. However, I turned and attacked a second bunch of landing craft with machine-gun fire at point-blank range with most satisfactory effect.” Ashby received the Distinguished Service Cross.

MTB-7 lost its port engine to shellfire, and the third one later. MTB-9 towed its sister to safety. MTBs 11, 12, and 26 were less lucky, all being sunk. Lieutenant D.W. Wagstaff of MTB-26 ignored the signal to withdraw, and the boat was last seen stopped dead off North Point, her Lewis gun blazing away. MTB-18 took a direct hit that wrecked her propeller. At top speed, she shot into the Kowloon seawall and exploded. There were no survivors.

The Punjabis and the Royal Scots tried to counterattack at 3 pm, with little success. The Royal Scots had a lot to prove after the fiasco at Shing Mun. They had not slept or eaten proper food in days, but were angry and insulted. Captain David Pinkerton, recovered from his Golden Hill wounds, again led the assault. The Scots advanced against heavy machine-gun fire and got nowhere. Pinkerton was wounded again on the steps of the police station and had to be removed from the battlefield, cursing horribly. Casualties were immense, and command devolved on four subalterns.

Of the 500 men who went into Wong Nei Chong Gap, only 175 returned after the battle. The Royal Scots had regained only their reputation. “This is the worst day my men had in all the Hong Kong fighting, and as an officer in battle the worst day I ever experienced,” wrote a Royal Scots subaltern.

The British tried again with two Volunteer armored cars and a hundred Indian artillerymen who had lost their guns. They reached the police station but could not hold it. In control of the gap, the Japanese beat and bayoneted the wounded defenders they captured.

By dusk on the 19th, the wrecked East Brigade had fallen back to Stanley. Royal Engineers blew up the two 6-inch guns at Collinson and the two 9.2-inchers at Cape D’Aguilar. The soldiers were tired and dispirited from days of bombardment and had neither the strength nor training for cross-country operations.

As night fell, both sides gasped for breath. Shoji scribbled out his report to Sakai, apologizing for the loss of 800 men to the Winnipeg Grenadiers. The stout defense by the green, scattered, and poorly supplied Canadians lifted Maltby’s spirits, but he could not counterattack yet. The Japanese were pressing on Repulse Bay Hotel and the Aberdeen dockyards. They would have to be held. He placed Colonel Harry Rose in charge of what was left of the West Brigade.

Early on the 20th, Wallis ordered the Royal Rifles to move along the south shore by Repulse Bay to counterattack toward Wong Nei Chong and hook up with West Brigade. Backed by his only two mobile 3.7-inch howitzers, A Company shuffled off to take Violet Hill, only to find the Japanese 3rd/229th had beaten them to it.

In peacetime, Repulse Bay Hotel offered its guests five-course meals, sandy beaches on a crescent-shaped bay, and beautifully tended gardens. It stood on the edge of a cliff and the foot of a mountain slope.

The three-day battle for the hotel began in bizarre fashion. At 7:40 am, four Japanese officers in white gloves and pressed uniforms turned up at the end of the driveway, staring at the terrain. Hotel guests eating breakfast on the terrace stared back in amazement. The officers vanished, replaced by 25 soldiers, who took over the hotel’s gas station and captured six Royal Navy sailors.

Fortunately, the hotel also had 200 British, Canadian, and Indian troops among its guests, soldiers who had been sent there for a few days’ rest from battle. They dug in immediately.

The civilian guests—paying £10 a day—were less prepared. They included the ubiquitous Gwen Dew, Baron and Baroness Guillaume, American author L.C. Arlington, Peak society matrons, and a collection of Swiss, French, Russian, German, and Chinese families. The socialites disliked the Chinese and complained about them to manager Marjorie Matheson, demanding they be put in the basement.

Instead, Matheson put civilians in the basement while the battle raged. British and Japanese soldiers traded rifle fire between the gas station and the hotel. Lieutenant Peter Grounds, commanding the defenders, led an attack to capture the gas station. He was killed leading it, but the sailors were freed, tied up but unhurt.

The siege continued. The defenders slept in the ping-pong and card rooms, rifles beside them, while the civilians huddled in the basement with rationed water. The hotel nurse, Elizabeth Mosey, tended shrapnel and stomach wounds. Luckily she had done that precise job in World War I. The senior staff cook and the female guests kept a flow of soup, coffee, sandwiches, and biscuits to the troops, holding back the caviar and lobster for a victory party.

By nightfall, the hotel battle was a stalemate, but Wallis was determined to recapture the Wong Nei Chong Gap. With rain drenching down, he decided to wait until dawn.

Next morning, Sunday, December 21, Major Robert Templer of the 8th Coast Artillery, a 20-year veteran, was sent to take over the Repulse Bay Hotel. “There’s a hell of a mess down there,” Maltby told Templer. “Try and clean it up, will you.”

With two Rifles platoons, Templer marched into the battered hotel to find the highest ranking officer hiding in the hotel bar, drunk, singing “The Maple Leaf Forever.”

Templer ordered all defenders to shave immediately and moved HQ to the hotel lobby. He restored order and boosted morale with personal leadership. Then he took two truckloads of Rifles up to attack a Japanese encampment, but found the enemy too numerous. That evening, Templer sat down for some turtle soup, supreme of turbot and filet mignon, when Bombardier Harry Guy reported, “Sir, them bloody Japs are in the West Wing.”

“The devil they are,” Templer retorted. “Come on.” He and a group of defenders went over with as many hand grenades as they could find.

A Japanese patrol had set up a machine gun at the end of a long, red-carpeted corridor, and were blazing away at the walls. Templer and his men rolled grenades down the floor to destroy the machine gun. The few guests left bailed out through the windows.

The battle for Wong Nei Chong Gap raged on. Grenadier Companies B and D, reinforced by some Royal Scots, Punjabis, and beached sailors, were sent to take back the police station. It took 10 hours to cover half a mile. Major Ernie Hodkinson led from the front, shouting, hurling grenades, and firing his revolver. When two armored cars came up to support the attack, Japanese mortars and machine guns shredded them. The platoon was halfway up the steep slope when the Japanese attacked from the crest, hurling grenades and screaming. Hodkinson was hit and blacked out. When he woke up, he was in Queen Mary Hospital, and he knew the attack had failed.

The Japanese continued their advance. Doi’s troops captured Mount Nicholson, breaking the defense line.

HMS Cicala was sent to Deep Water Bay to provide fire support. She came under enemy mortar fire and silenced the mortars with 6-pound shells. “No more trouble from that quarter,” Boldero observed.

But the Japanese came back with six bombers, and Cicala’s luck finally ran out. Bombs blasted her open. She was sinking by the stern when more bombers came streaking in. Boldero signaled MTB-9 to ask what to do, and was told to “drop depth charges and make sure she sinks.” Boldero was the last man onto the Carley floats. The depth charges blew up, and HMS Cicala sank at last. The sailors rowed back to Aberdeen, where they were issued rifles and tin hats. Four hours later, they were fighting as infantrymen on Bennett’s Hill.

Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Kidd personally led his Punjabis to fight their way through from Aberdeen to Repulse Bay. With only 25 Sikhs and a dozen sailors, Kidd attacked Shouson Hill, which was topped by a mansion belonging to Sir Shouson Hill, a Chinese millionaire. Captain Alastair Thompson and Lieutenant Nigel Forsyth led their men into action, which was fought at close range. A Sikh sergeant bayoneted three Japanese and hurled their bodies over his shoulder like sacks of hay. Another corporal killed five with a single Thompson burst. Two sepoys held off 20 Japanese with their rifles until they were killed.

But the hill had no cover, and the British had no artillery support. The attack failed, and Kidd lay among the dead. Thompson was also wounded, but Forsyth emerged unscathed. The surviving eight Sikhs pulled out for tea and rum.

All day the Canadians launched piecemeal counterattacks, taking heavy casualties. They were joined by all the rear-echelon men Western armies rely on. All failed.

No help was coming. Chiang Kai-shek radioed that he could not attack toward Hong Kong for another 10 days, if at all. The War Office ordered Maltby to destroy all installations. Volunteers set the Texaco, Shell, and Royal Navy oil tanks ablaze, covering Victoria in blue flame and smoke. Grenadier Sergeant Howard Donnelly was ordered to destroy a liquor warehouse, and he did—but not before stuffing his tunic with bottles.

The battle of the Repulse Bay Hotel resumed on the 22nd. Guests volunteered to help. Millionaire Henry Marsman slapped on a tin hat and went out with two Chinese bellboys in red caps and gold-buttoned uniforms to dig in the garden to fill sandbags. Hong Kong’s best jockey, Victor Needa; British businessman D.A. Baker-Carr; and Canadian oil executive W.M. Wilson drove a bullet-riddled car half a mile to the Lido Beach Club to pick up a British ammunition cache. Miraculously, all three survived.

The hotel itself was now a mess—full of broken walls and floors, shattered glass, falling plaster, wrecked silverware, and bullet-riddled furniture. The Japanese cut off water and power, and Templer rationed water to a cupful per day. Dew and Mosey—the latter in her old uniform—washed bandages in the same water over and over again.

Hearing about this situation by radio, Maltby ordered Templer to withdraw the troops and leave the guests and wounded men to surrender. Maltby feared that if any more fighting took place in the hotel civilians would die needlessly. Templer was appalled. “It was the most terrible order I have ever had to give—the order to abandon women and children to the Japanese. But I realized that Maltby had been right: Stanley was hardly the place for 200 unexpected civilian guests.” He had to repeat his orders in Hindustani for the Indians and French for the Canadians.

The troops destroyed the liquor stores and withdrew during the night of the 22nd. They said nothing, to prevent panic, but some of the civilians came to see them off. Businessman Andrew Shields told Templer, “You’ve got to go. We all realize that. Only men with rifles are important in Hong Kong now.” Templer nodded, turned on his heel, and gave the order: “Ready to move.” The men slipped down the drain tunnel to the beach, then south along the road to Stanley Fort, sneaking past a patrol of 20 Japanese. Every man took off his heavy hobnailed boots to reduce the noise, and all made it to Stanley.

At dawn on the 23rd, guests awoke to see a white pillowcase fluttering from the garden flagpole that had flown the Union Jack. The Japanese arrived three hours later through the back windows, suspecting a trap. Businessman Andrew Shields said in poor Japanese, “There are no soldiers here, soldiers gone.”

Six Japanese pointed their bayonets at the cocktail bar where 40 men lay wounded. Mosey looked up from a dying Alberta soldier who was talking lucidly of his family back home. She snarled, “Go away. These are sick men. If you want to kill them, you’ll have to kill me first.” The Japanese retreated. “That’s better,” she said, returning to the Canadian. There were no killings at the Repulse Bay Hotel.

The British were pulling out of the Ridge, south of Wong Nei Chong Gap, as well. Lt. Col. MacPherson was holding the place with a collection of Royal Army Ordnance Corpsmen. They spoke in French to prevent listening Japanese from understanding the orders. Again, the British left their wounded behind, but when the Japanese stormed into their house, they tore down the white flag, bayoneted the interpreter, and sprayed a room full of 30 wounded men with machine-gun fire and grenades, killing most of them. Six days later, the bodies were found, heaped in a pile like rubbish.

The same day, 53 Rifles and British POWs were marched to a seaside cliff near the Repulse Bay Hotel. There the Japanese bound the men, and then shot, bayoneted, and beheaded them in groups.

Fifth columnists led Japanese troops to the Happy Valley Racetrack. There, 50 defenders were assembled to hold the valley, including civilian police. Thirty-five Middlesex men and seven Volunteers held Leighton Hill with rifles and machine guns, taking all the artillery the Japanese could muster in Kowloon. They only withdrew on Christmas Eve. In Wanchai, Royal Scots and Volunteers fought for four hours to hold Jimmy’s Beer Kitchen, a four-story building that was normally the troops’ favorite bar.

All along the mountains the fighting raged on. Doi was stunned by the Canadian ferocity. He thought he was up against 400 men in one fight, when the Grenadiers only numbered 100. Doi’s men took 40 percent casualties and ran out of ammunition. They hurled rocks at the Canadians. The Grenadiers, also short of ammunition, threw packing crates and machinery back.

As the casualties mounted, organization disintegrated. Japanese shellfire blasted the phone lines. Runners got lost and shot. With food and ammunition short, Canadians jumped enemy sentries to steal their food. Grenadiers went three or four days without eating.

Winston Churchill was worried, too. From the battleship HMS Duke of York, taking him to a conference in Washington, he signaled Hong Kong on the 21st: “Every day that you are able to maintain your resistance you help the Allied cause all over the world, and by a prolonged resistance you and your men can win the lasting honor which we are sure will be your due.”

Strong words, but the Japanese had taken three reservoirs and bombed the fourth, cutting off the water. Victoria’s 1.7 million residents had only wells and rooftop tanks. Enterprising Chinese sold jugs of dirty water for $10 a bottle. Grenadier Sergeant Howard Donnelly grabbed a gasoline tanker to bring water from a well to his Peak depot and used the water to cook food. The eggs tasted of gasoline, but he touched a match to them and they didn’t catch fire.

Victoria itself was a nightmare. Refugees lined up for food amid rubble and the bodies of shot looters, left by police as a warning. Black marketeers sold flashlights, blankets, and food. Women guarded their homes with guns, and white residents carried the bodies of relatives and friends killed in the shelling up slopes, looking for somewhere to bury them.

With Victoria collapsing, Doi hurled his men at the center of the British line, Mount Cameron, on the night of the 23rd. One thousand men of the 228th Regiment stormed a hill held by a hundred Grenadiers. The Canadians were scattered, but regrouped. The Royal Scots also fought hard, losing 390 of 500 men in the center of the island.

At Stanley peninsula, the Volunteers and Royal Rifles held on against Tanaka’s 229th Regiment. Middlesex 2nd Lt. Charles Cheesewright held his pillboxes until midnight on the 22nd, when he was ordered to withdraw. Incredibly, his No. 11 Platoon did not suffer a single casualty.

Major Rusty Forsyth led No. 2 (Scottish) Company of the Volunteers in a fierce stand against Japanese troops and tanks. He was wounded twice but continued to fight. Above the din of battle came the sound of bagpipes as Pipe Major Alexander Mackie skirled away. The company was ordered to withdraw, but nobody obeyed the orders. Forsyth was killed, and Mackie played on. The Japanese yelled, “Surrender, Englishmen!”

The Scots yelled back, “Englishmen be damned!” The next round of Japanese gunfire killed Mackie.

The Royal Rifles were exhausted, too. Some Canadians were passing out and falling asleep where they stood, oblivious to bombardment. Issued new entrenching tools, they were too tired to dig.

The Rifles lost Stone Hill, Palm Villa, and Sugar Loaf Hill. Stanley Mound changed hands three times. Private Sidney Skelton wrote in his diary: “Death and blood all around me. They just got Jack next to me. We were talking when suddenly a shell made a mess of him. Today Mother’s birthday. I wonder if she’s thinking of me. Noise all around. They are coming closer. Oh, God, it doesn’t seem that I can stand it any longer.” Skelton was wounded soon after, and taken to St. Stephen’s College in Stanley, which was being used as a hospital.