By Patrick J. Chaisson

The GIs defending Pillbox No. 9 watched in despair as a weak January sun set behind them. All day long they had beaten back repeated enemy infantry, tank, and flamethrower attacks, but with the coming of night their concrete fortification seemed more and more like a deathtrap.

Captain William Corson, the company commander, led Pillbox No. 9’s garrison of 100 untried American riflemen. Their ammunition was almost gone, though, and communications with higher headquarters had been cut for hours. Worse, inside Corson’s bunker were collected a dozen wounded men who urgently required medical care.

He had orders to hold at all costs, but Captain Corson knew the growing darkness would bring with it a renewed enemy assault that his exhausted troops simply did not have the means to resist. In a desperate attempt to contact HQ, the young officer moved to a sheltered observation platform where his low-powered “handie-talkie” radio might connect with the battalion command post.

Just then a German artillery shell exploded overhead, severely wounding Corson and killing a nearby private. Command of Pillbox No. 9 passed to T/Sgt. Al Cahoon, the senior NCO present. Cahoon remembered considering his options: “I thought we might try to withdraw, but we would have been cut down if we tried. So we held tight in the pillbox.”

Later, the sound of men working outside forced Cahoon to make another decision. He recalled how “we could hear the Jerry engineers on top of the pillbox stuffing nitro-starch down the ventilating tubes.” After a quick conference with the injured Corson, Cahoon yelled to an English-speaking German officer at the door that his soldiers were surrendering. The weary, dispirited GIs emerged from their underground shelter one by one with hands raised.

But the defenders of Pillbox No. 9 had held out for 19 precious hours. Their sacrifice bought time for U.S. commanders to rush reinforcements forward in an attempt to contain the enemy’s advance. Over the next 11 days, Hatten—a once-tidy community of 350 houses—would draw fighting men from three American divisions into a titanic struggle against German Panzergrenadiers (armored infantry) and Fallschirmjäger (paratroops). At stake was the entire Allied right flank in Western Europe.

The maelstrom of Hatten occurred during Operation Nordwind, Nazi Germany’s last counteroffensive in the West. Adolf Hitler and his generals initiated Nordwind two weeks after launching their Ardennes campaign, an operation known today as the Battle of the Bulge. Nordwind was designed to exploit perceived Allied weaknesses south of the Bulge penetration, a situation created when Allied armies stretched their lines to cover a sector previously held by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s command then counterattacking into Belgium and Luxembourg.

Nordwind was a sequential plan. First, four infantry corps were ordered to penetrate Seventh U.S. Army’s defensive belt in the northern Alsace region of France on New Year’s Night, 1944-45. Once those units breached the enemy’s brittle front line, a powerful mechanized column would punch through to seize the strategic Saverne Gap, 25 miles behind the Americans’ forward positions. This maneuver was designed to isolate Seventh Army, which could then be destroyed in detail.

It did not work out as planned. The Germans’ initial assaults, which began after midnight on January 1, 1945, bent but failed to break Seventh Army’s defenses. By January 6, the first phase of Operation Nordwind had sputtered out with little to show other than a long list of casualties.

Forty miles east, however, other German troops had managed to establish a bridgehead across the Rhine River at Gambsheim on the morning of January 5. This successful crossing presented a fresh opportunity to achieve Hitler’s operational objectives. Beginning that evening, thousands of soldiers and hundreds of armored vehicles belonging to XXXIX Panzer Corps (Nordwind’s exploitation force) made their way by ferryboat over the Rhine to Gambsheim. Their goal: smash a hole in Seventh Army’s overextended line, then race for the all-important mountain pass at Saverne.

Ten miles northwest of the Gambsheim bridgehead stood the village of Hatten. This farming community of 1,500 residents was militarily significant due to its position astride the primary high-speed avenue of approach leading west toward Saverne. Together with such neighboring crossroads as Kilstett, Sessenheim, and Rittershoffen, Hatten represented an easily defended strongpoint which had to be captured before XXXIX Corps could start its envelopment of Seventh U.S. Army.

The terrain in which the two adversaries fought was, according to one American combatant, “as flat as a billiard table.” Snow-covered farm fields predominated, although several large forests restricted both visibility and maneuver. A number of eastwardly flowing streams cut the landscape, but their shallow banks presented no obstacle to tactical movement. The region’s road network supported both wheeled and tracked vehicle traffic.

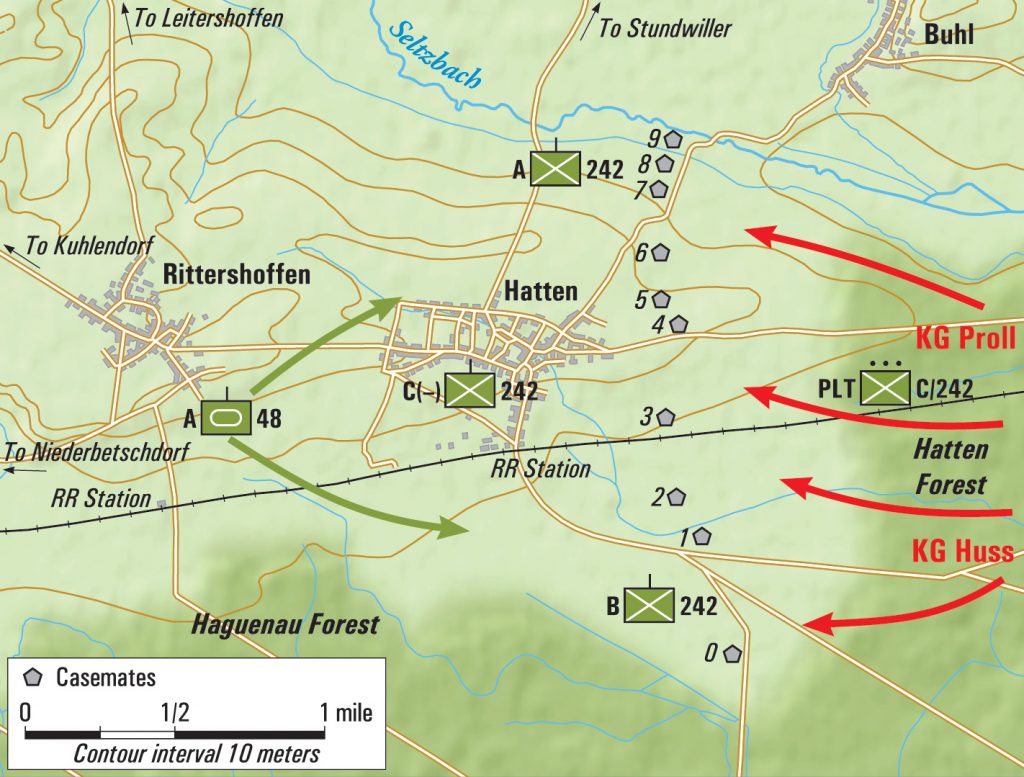

A line of 10 pre-war Maginot Line blockhouses stood just outside Hatten to the east. These battlements, labeled Pillboxes 0 through 9 on U.S. maps, stretched from the Haguenau Forest south of town to the Seltzbach River along its northern edge. Another concrete emplacement in the village’s west end provided shelter for those men not standing guard outside.

By January 8, XXXIX Panzer Corps was across the Rhine and poised to attack. At the tip of this armored spear was the 6,500-man 25th Panzergrenadier Division (PgD), heavily augmented by combat engineers, flamethrower tanks, and bunker-busting assault guns. Several batteries of 105mm and 150mm howitzers, along with mortars and rocket artillery, stood by to provide indirect fire support.

In preparation for its assault, the 25th PgD task-organized into flexible battle groups. Kampfgruppe Proll, a mostly-dismounted contingent named after the 35th Panzergrenadier Regiment’s commanding officer, would take the Maginot Line fortifications east of town known to be held by American troops. Then, once Proll’s men opened the way, a strong mechanized formation called Kampfgruppe Huss (named for the 119th Panzergrenadier Regiment’s commander) was to head for Saverne.

Gathered in the woods west of Hatten were some 1,050 infantrymen, along with at least 16 PzKpfw. IV medium tanks and 20 SdKfz 251 half-tracked personnel carriers. A number of Hetzer 38(t) Flammpanzers (flamethrower tanks) and Jagdpanzer IV assault guns also awaited the order to advance. For many foot soldiers, recently transferred from the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe, this would be their first battle. These former sailors and airmen were sent forward without benefit of proper infantry training to bolster the panzergrenadiers’ ranks just prior to Nordwind.

Set to exploit the attack was the rest of XXXIX Panzer Corps. Its primary maneuver element consisted of the 12,100-man 21st Panzer Division, equipped with an estimated 34 PzKpfw. IV and 38 PzKpfw. V Panther medium tanks. Another 1,200 tough, combat-tested paratroopers of the 20th Fallschirmjäger Regiment acted as XXXIX Corps’ reserve.

Arrayed against this formidable enemy presence was a U.S. infantry battalion that had never before seen combat. Beginning on January 5, 1945, the 780 men of the 1st Battalion, 242nd Infantry Regiment (1/242) began occupying Hatten. In command was Lt. Col. Edwin Rusteberg, 33, of Brownsville, Texas.

Rusteberg’s battalion was part of an unorthodox solution to the Allies’ theater-wide shortage of riflemen. Back in November, his parent division (the 42nd “Rainbow”, so-named for the colorful shoulder patch its members wore) was directed to send its three infantry regiments overseas early. Those 9,800 men, organized into a task force (TF) designated TF Linden (named for its commander, Brig. Gen. Henning Linden), disembarked at Marseilles on December 8-9, 1944.

Christmas was spent on the front line, near Strasbourg in eastern France. On January 2, 1945, General Linden received orders attaching his command to the U.S. 79th Infantry Division. Known as the “Cross of Lorraine” Division for its distinctive unit insignia, the 79th was an extremely experienced formation. Its troops had been fighting almost without pause since they landed on Utah Beach one week after D-Day.

The 79th Infantry Division’s commanding general, Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche, was glad to receive Linden’s soldiers. Wyche needed every available rifle, as his organization was responsible for defending an impossibly long defensive sector. In early January its line, according the 79th’s history, stretched “from Wissembourg east to the Rhine, a distance of 20 miles, in addition to 30 miles along the Rhine River.”

Even as the first phase of Operation Nordwind raged well to the east, things remained quiet in the Cross of Lorraine Division’s sector. This permitted Brig. Gen. Linden’s troops to settle in and start gaining combat experience. Wisely, Maj. Gen. Wyche positioned these inexperienced regiments in between his own battle-tested organizations to help speed the adjustment process.

Supporting so many soldiers over such an extended distance proved difficult, however. The 79th Infantry Division simply did not possess a logistics backbone sufficient to keep TF Linden supplied with food, ammunition, and fuel while simultaneously meeting its own daily requirements.

Those sustainment assets so badly needed in France were back in New York harbor, being loaded onto cargo ships. Allied planners had taken a calculated risk by sending Linden’s infantrymen forward early and without the remainder of their parent division. Thousands of young Americans would soon pay the price for this decision, which deprived them of proper supplies, signal equipment, and artillery support at a most critical time.

Meanwhile in Hatten, Lt. Col. Rusteberg faced a more immediate problem. His field manuals told him a battalion frontage should not exceed 800 yards in such terrain; now this West Point-trained officer was being ordered to “hold at all costs” along a line stretching 4,200 yards. And while those Maginot fortifications east of town looked inviting to cold, tired riflemen, they could be destroyed easily if left unprotected against surprise attack.

With three paltry 57 mm antitank guns in its AT platoon plus some Bazooka rocket launchers distributed across the battalion, 1/242 could do little to resist a determined panzer assault. Rusteberg’s regimental commander, Colonel Norman C. Caum, understood this and forwarded nine additional 57mm guns from his AT company, as well as four tracked M10 tank destroyers (TDs) belonging to the attached 813th TD Battalion. The 242’s Cannon Company (boasting six 105mm howitzers) also deployed nearby.

To the south stood 3rd Battalion (3/242), while 2nd Battalion (2/242)—bloodied while resisting the German river crossing at Gambsheim—recuperated in Rittershoffen one mile to the west. The 79th Infantry Division’s 3rd Battalion, 313th Infantry Regiment (3/313) held defensive positions on the northern flank. Another Cross of Lorraine rifle battalion (3/315), along with elements of the 14th Armored Division, acted as reserve. The 311th Field Artillery (FA) Battalion fired in direct support with its dozen 105 mm howitzers.

Rusteberg did his best to organize a suitable defense. In the north, Captain Bill Corson’s Company A anchored its foxhole line on Pillbox No. 9 overlooking the narrow Seltzbach River. Farther south stood Company B, headed by Captain Benjamin F. Montague, its right flank resting inside the Haguenau Forest. Company C (1st Lt. James M. Long, commanding) remained in Hatten as battalion reserve. Captain William J. Rochelle’s Company D (heavy weapons) emplaced its .30-cal. machine guns and 81 mm mortars to cover the entire two-mile-long main line of resistance (MLR).

With sound-powered field phones connecting him both to regiment and all sub-unit commanders, Lt. Col. Rusteberg next set about establishing an early warning network. Turning to T/Sgt. Merl H. Todd, one of his few combat veterans, Rusteberg directed that seasoned NCO to occupy a listening post in the Hatten Forest approximately 800 yards forward of 1/242’s MLR. Todd, who had been wounded twice during a previous tour of duty with the 3rd Infantry Division in Italy, took 21 members of 1st Platoon, Company C, out with him starting at midafternoon on January 8.

“You could say that we were prepared for a big battle,” recollected Sergeant David Willetts, who accompanied Todd on this hazardous mission. “Each soldier carried extra belts of 30-cal. ammunition and extra grenades.” After settling in, according to Willetts, “the long, dark, cold night fell upon us, and the very tense waiting, watching, and listening began.”

Todd’s detachment did not have to wait long for their “big battle.” Under cover of an intense artillery barrage, hundreds of German riflemen and combat engineers began to move forward shortly after midnight on January 9. These men belonged to Kampfgruppe Proll, the foot-mobile assault group charged with cracking 1/242’s Maginot Line fortifications.

A 19-year-old panzergrenadier named Hans Weiss took part. “(Our) order to attack came at 0500,” he later wrote of the battle. Weiss and his comrades “came out of the woods and were greeted by an intense artillery barrage. [We] were pinned down and…suffered [our] first casualties almost immediately.” At dawn, the young private could see his objective, Pillbox No. 2, still 250 meters away.

Along the MLR, meanwhile, 1/242 had gone to full alert. Staff Sergeant Raymond E. Hodde, a machine-gun section leader in Co. D, vividly recalled Kampfgruppe Proll’s pre-dawn attack. “At 5 o’clock it seemed that all hell broke loose. ‘They’re coming!’ my gunner shouted. Crouched shapes moved toward us across the snow-covered field. Shells screamed overhead and burst to the rear of us. The roar of their guns was deafening.”

The GIs fought back hard. Al Cahoon described the morning’s encounter at Pillbox No. 9: “Directly to the front of my position, all we had to contend with was Infantry attacks and we turned them all back with heavy losses to them. We had excellent fields of fire and I thought at the time ‘what a waste of manpower and how strange that they even attempt to attack over such wide openly exposed terrain.’”

Not far away, however, Captain Corson saw his supporting tank destroyers pull out of position behind him and scurry for safety. In the battalion’s center sector, German infantry and flamethrower teams captured two bunkers that guarded the main road into town. Some panzergrenadiers, clad in white camouflage capes, even managed to work their way inside Hatten.

Rusteberg sent his reserve, Company C, forward to restore the MLR at 7:45 am. By then, though, 1/242’s 57 mm AT guns had all been destroyed. The battalion’s antitank arsenal was now reduced to a few short-ranged bazookas and rifle grenades—weapons that would prove wholly inadequate against a dangerous new threat that came storming out of Hatten Forest at about 11:00 am.

This new threat was the Kampfgruppe Huss, the mechanized exploitation force set to begin its advance on Saverne. Also heading toward town were a number of flammpanzers (flame-throwing tanks) and heavy assault guns, vehicles purpose-built to defeat concrete emplacements.

In 1/242’s command post (CP), Lt. Col. Rusteberg received a radio report at 11:18 from Company B that tanks and personnel carriers were approaching Pillbox No. 1 to the south. Messengers from Company A soon confirmed that a major attack was in progress. Rusteberg passed down orders to “hold positions, let tanks pass, and fire at the enemy foot troops.”

Mortarman S/Sgt. Lloyd B. Oczkewicz, at Pillbox No. 4, said he “could see the Jerries were using flame-throwing tanks firing into the bunker to our right. We realized that now we were trapped in the pillbox.” Oczkewicz never forgot the awful feeling that came over him when he realized he was about to become a prisoner of war. At noon, Pillbox No. 4’s 20-man garrison gave up to a German NCO and was marched into captivity.

While elements of Kampfgruppe Huss worked to reduce these bunkers, other armored fighting vehicles bypassed Hatten to the north. Standing in their path was a platoon of 57 mm guns belonging to the 242nd Infantry Regiment’s antitank company. Private Donald O. Johnson remembered his outfit’s brief encounter with the marauding Panzers: “It was about 1500 that I saw a tank right by the Second Squad’s gun,” Johnson reported. “Our 57 mm was ready. We fired once; we fired twice. The third firing came the other way.”

A volley of well-aimed high-explosive rounds obliterated Johnson’s gun emplacement, leaving the 21-year-old GI stunned. He regained consciousness to find a young panzergrenadier standing over him. “The German was motioning for me to get my hands up,” Johnson noted. “My right arm wouldn’t work. Apparently, a log had fallen on my shoulder, so I used my left hand to hold my right hand up. I was a prisoner of war.”

Visiting 1/242’s CP when the second German attack struck was Captain Joel P. “Ace” Ory, commanding Company A, 48th Tank Battalion, 14th Armored Division. Ory raced back to his outfit (in reserve at Rittershoffen) and at 2:20 pm sent forward Lieutenant Edgar D. Woodard’s platoon of five M4 Sherman medium tanks to counter this new threat. “Tanks on your right—German tanks— in the valley,” Ory told the young officer. “Get’ em … you can’t miss, hurry!”

Taking up a hide position in the Haguenau Forest south of town, Woodard’s tankers “waited for the attack we knew was coming. We didn’t have to wait long. Six German tanks began moving along the railroad track from Hatten. They were on our left, and they apparently didn’t see us, so we let them get within 600 yards. Then we let go. A Mark IV was leading the advance. One of our tanks opened fire, and before the Krauts knew what was coming off, had poured four rounds into the hull. The tank went up in flames.

“The other tanks in my platoon had opened up,” Woodard continued, “and within five minutes, all six of the German tanks were knocked out. They were so damned surprised they didn’t fire a shot back at us.”

Back in Hatten, 1/242’s situation was deteriorating rapidly. Enemy shellfire destroyed an observation post in the Catholic church’s steeple, which drastically curtailed artillery support. German forces were also methodically demolishing the Americans’ Maginot Line fortifications, compelling those stationed there to either surrender or flee back into town. No one had heard from Company A or Company B in hours, while Company C’s first sergeant took temporary command after all that unit’s officers had become casualties.

As dusk approached, the outpost detachment under T/Sgt. Merl Todd was still fighting from a position in the woods deep behind enemy lines. “We are giving them hell out here,” he reported before the phone line went dead, but with ammunition running low it was time to withdraw. Earlier, Todd had been shot in the leg; now he led his remaining soldiers out of Hatten Forest while “limping along leaving a bloody trail behind him,” according to eyewitness Private Robert Christian.

Some men blundered into a patrol of panzergrenadiers and were made prisoner. Others, including Christian, managed to slip past German sentries. Unfortunately, Todd perished 200 yards from safety when a U.S. machine- gun team mistook him for the enemy. For his valor in combat, T/Sgt. Merl H. Todd received posthumous award of the Distinguished Service Cross (adding to the two Silver Stars he had earned in Italy).

Meanwhile, inside Hatten, veteran panzergrenadiers accompanied by Panther tanks and assault guns began advancing house to house against 1/242’s remaining defenders. But army clerks, radiomen, and staff officers fought furiously to blunt the enemy’s advance. One GI, a nearsighted cook named Pfc. Vito R. Bertoldo, became an unlikely hero when he almost singlehandedly held off an afternoon attack on the battalion CP.

Rusteberg recalled the incident: “I could see Vito Bertoldo and his MG [machine gun] mowing down a column of German infantry following a tank belching forth its solid shot and MG fire into our building at point blank range.” At least 20 panzergrenadiers fell under Bertoldo’s fire.

It was time to abandon the CP. With Bertoldo covering their withdrawal, the command post staff moved their HQ into a butcher shop toward the center of town. Colonel Caum, the regimental commander, made a brief visit there at 8:30 pm. Before departing, Caum told Rusteberg to hold on a bit longer as a dawn counterattack was in the works.

Indeed, 2/242’s Company G had already come up to strengthen defenses in Hatten. Yet intense fighting continued well past midnight, even forcing Rusteberg to relocate his CP a second time. German officers also had plans for sunrise, as the Americans would shortly learn.

In the meantime, Hatten burned. Flamethrowers, phosphorus grenades, and incendiary ammunition set alight many of its wooden structures, forcing combatants and civilians alike to run for cover. Snipers, tank crews, and machine-gun teams slaughtered anyone caught out on the street. All night, small groups of bleary-eyed GIs peered anxiously from their hideouts in the western part of town and awaited reinforcements.

Help was on the way. At dawn on January 10, two rifle companies from the battle-tested 2nd Battalion, 315th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division (Lt. Col. Earl F. Holton, commanding), fought their way into Hatten. Once inside town, though, Holton’s men went to ground. A massive German counterattack had just commenced, one that threatened to crack the entire U.S. position wide open.

Several dozen enemy vehicles moving around Hatten to the north crashed into B and C Companies of the 48th Tank Battalion, assigned to support 2/315’s assault. Both sides traded blows for a full hour before the panzers pulled back. “We knocked out plenty of German tanks,” said Captain John D. Wilson of Company C, “but not without great loss to ourselves.”

Battling alongside the 48th’s veterans were 12 M18 Hellcats belonging to Company B, 827th TD Battalion. This unit comprised African-American gunners commanded mostly by white officers; heretofore labeled a “hard-luck” outfit, that day the 827th proved it could fight as well as anyone regardless of race.

Four M18s under 2nd Lt. Robert F. Jones made it inside Hatten, where they went into action immediately. A 79th Division historian picks up the story: “Three tanks of the German force swept close around the west end of the south main street of Hatten. One of Jones’ tank destroyers, commanded by Sergeant Spencer Irving, was hidden by houses … at the southwestern corner; and Irving could see the unsuspecting Panzers coming. They crossed the Hatten-Rittershoffen road and Sergeant Irving brought his tank destroyer out of hiding and lined up his targets before the Panzers could swing about into firing position.”

Accompanying infantrymen “swore that Irving, standing up in his turret, turned and called to them, ‘How do you want them? One, two, three, or three, two, one?’ He then picked off the three Panzers ‘one, two, three.’”

From the top floor of a wooden dwelling, Pfc. Bertoldo continued to rage his one-man war against attacking panzergrenadiers and armored vehicles. Strapping his machine gun to a table, Bertoldo kept the foe pinned down until mid-afternoon, when an assault gun targeted his position with a high-explosive shell. Miraculously unhurt by the blast, he quickly returned to his perch in time to ward off another German thrust at sunset.

An official Army citation described what happened next: “The enemy began an intensive assault supported by fire from their tanks and heavy guns. Disregarding the devastating barrage, [Bertoldo] remained at his post and hurled white phosphorous grenades into the advancing enemy troops until they broke and retreated. A tank less than 50 yards away fired at his stronghold, destroyed the machine-gun and blew him across the room again; but once more he returned to the bitter fight and, with only a rifle, single-handedly covered the withdrawal of his fellow soldiers.”

For his gallantry at Hatten, Pfc. Vito R. Bertoldo received the Medal of Honor.

After dark, Lt. Col. Rusteberg got the order to withdraw. This maneuver, difficult to accomplish even under ideal circumstances, was made infinitely more complicated by the tactical situation. Enemy forces had completely encircled Hatten and were even then fighting against U.S. infantry inside Rittershoffen. To reach safety, the men of 1/242 would have to infiltrate through German lines in small groups.

Technician 5th Grade Rudolph A. Wodgenske and two comrades set out under a “full moon and cloudless sky decorated with twinkling stars,” as he wrote years later. Creeping for nearly one mile across a “flat and barren field,” Wodgenske’s group managed to sneak around the enemy’s outposts. “Crawl about 50 yards,” he remembered of the ordeal, “hear a flare go up, hear the guns roar and ‘freeze.’” Finally, at sunup all three men made it to friendly positions, where they were given dry socks and a hot breakfast.

Among the last members of 1/242 to evacuate Hatten was its commander, Ed Rusteberg. Together with Captain Bill Rochelle of Company D (his one company commander not wounded or captured), the weary colonel set out toward friendly lines just before dawn on January 11. Left behind to continue the fight were Lt. Col. Holton’s battalion and Lieutenant Jones’ doughty tank destroyer crews.

The battle of Hatten-Rittershoffen would go on for another nine terrible days. Together, these two small villages acted as a cauldron into which were poured men, matériel, and firepower in ever-increasing quantities. Nearly 10,000 men of the 79th Infantry Division, as well as the entire 11,000-soldier 14th Armored Division, struggled mightily against a similar number of German troops for possession of this key terrain. When combat ceased on January 20, the towns of Hatten and Rittershoffen had been flattened. Over 100 innocent civilians, unable to escape the destruction, perished in the ruins of their homes.

Later, a U.S. survey tallied 31 derelict M4 Shermans, nine M5A1 light tanks, and eight half-tracks found on the battlefield. They also counted 51 destroyed German panzers and assault guns, plus 12 soft-skin personnel carriers. No comprehensive accounting of the battle’s human cost has ever surfaced.

It took weeks for the men of TF Linden to rebuild from the losses they had suffered at Hatten-Rittershoffen. Yet these untested American riflemen—in their first fight against terrifying Panther tanks and elite panzergrenadiers—had performed magnificently. Ordered to defend an extended line against overwhelming odds, they had done just that for 52 crucial hours. The 1st Battalion, 242nd Infantry Regiment entered Hatten with 33 officers and 748 enlisted men; after two days of bitter fighting only 264 GIs remained in its ranks. The rest were recovering in the hospital, dead on the field, or on their way to a German prison camp.

Lieutenant Colonel Rusteberg later complimented his troops, saying they achieved their mission “even though surrounded and cut to pieces by an enemy superior in number and supported by armor.” Through it all, he noted, “Not one man shirked his duty—not one man left Hatten until relieved.”

The U.S. Army awarded its Presidential Unit Citation to many of Hatten’s defenders. Rusteberg’s 1/242 and Holton’s 2/315 were both so recognized, along with the 242nd Anti-Tank Company, Lieutenant Woodard’s 1st Platoon, Co. A, 48th Tank Battalion, and several other organizations that had also fought there. This honor stands as a fitting tribute to those grimly determined servicemen who in January 1945 held Hatten “at all costs.”

Frequent contributor Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer and historian for the Rainbow Division Veterans Foundation.

Amazing story of courage and determination! Thank you for writing this.