By Raymond E. Bell

At the town of Schmidt in the Hürtgen Forest, it was hard to see through the thick mist and steady drizzle on the cold and damp morning of Saturday, November 4, 1944. Bomb craters filled with rainwater dotted the bleak landscape. The spongy ground sucked at soldiers’ boots, and thick mud clung to their leggings and pants, adding to the misery of fighting in the woods in the rain with little sleep.

Suddenly, rounds from German howitzers whooshed downward and slammed into the ground, causing it to shake like an earthquake. For the next half hour, the Germans pummeled the town with their heavy artillery. When the big guns stopped, the American riflemen heard the clanking of tanks. The woods were soon alive with German infantry. The deadly krump of mortars and the chatter of machine guns filled the air.

GIs armed with bazookas tried in vain to stop PzKpfw.IV and PzKpfw.V Panther tanks. Their shells bounced harmlessly off the steel monsters. The tanks roamed at will through the town, hunting Americans in houses or in foxholes. “The tanks … had smashed through the two forward company positions and broke them all to hell,” said Captain Guy T. Piercey, commander of a weapons company. “The situation was bad.”

Overwhelmed by the Germans’ staggering firepower some of the GIs fled from their positions at 8:30 AM. Ninety minutes later, the rest of the 3rd Battalion, 112th Infantry Regiment quit Schmidt. They disappeared into the forest leaving their dead and wounded to the Germans.

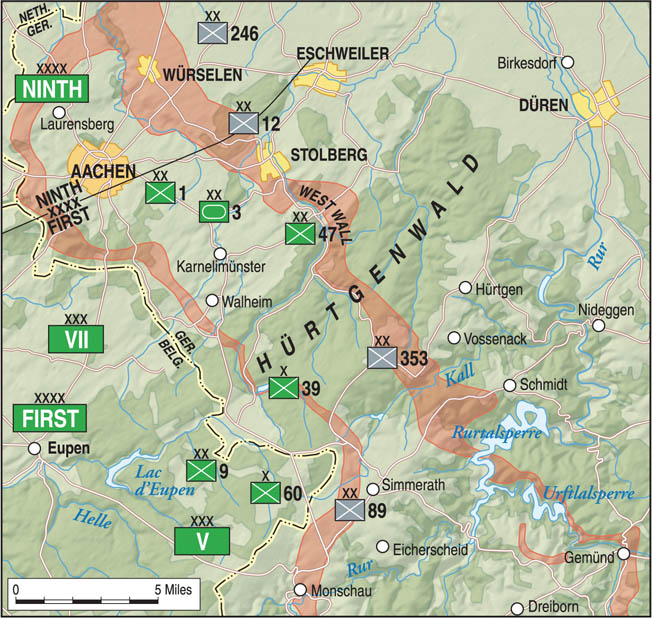

The German counterattack at Schmidt was indicative of the setbacks Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges’ First Army experienced in the Hürtgen Forest from mid-September 1944 to early February 1945. The story of the battle begins just before the capture of Aachen, the first large city in Germany to fall to the Americans. Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division had advanced in September into the Stolberg corridor between Aachen and the Hürtgen Forest, putting the Allies within 20 miles of the Rhine River.

The division’s right flank came to rest on the northwest rim of the forest. On September 13, the division made an incursion into the forest in the vicinity of the town of Roetgen. The crack armored division, however, was pointed to the east beyond the Siegfried Line, or the West Wall as the Germans called it, so it did not become embroiled in the forest. As the division advanced, it also took the small villages of Schmidthof, Rott, and Brandt peripherally located on the Hürtgen Forest’s northwestern edge. As a result of the division’s eastward attack, the incursion was a brief encounter with a dense evergreen forest that soon completely thwarted the troops of Hodges’ First Army.

On its way to the Battle of Aachen, Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s vaunted 1st Infantry Division had encountered the German defenses on the northwestern fringes of the Hürtgen Forest. Division troops attacked Aachen from the south, which resulted in limited contact with the foreboding woods as they advanced north to encircle the city. Just like the 3rd Armored Division, it was to be saved the agony of the forest and its elaborate defenses, but it suffered nevertheless. The 1st Infantry Division, though, was not to see the last of the forest.

There were two striking characteristics about the forest battle. The first was the nature of the woods and the German defenses inside the woods. The second was the complete inability of Hodges and First Army Headquarters to appreciate the challenges of fighting in such an environment. First Army troops would have a horrific experience in the front line in the woods, while the headquarters staff reamined in comfort, removed from the intense fighting and great suffering.

The Hürtgen Forest is actually three woods: Wenau, Hürtgen, and Rotgen. The dark evergreen forest lies on the border of Belgium and Germany and astride the West Wall. It occupies a 50- square-mile, triangle-shaped area bounded by the towns of Aachen, Duren, and Monschau. Two ridges are angled southwest to northeast through the forest toward the Roer River. The village of Hürtgen is located on the northern ridge, while the town of Schmidt is situated on the southern ridge. Between them the Kall River flows through a forbidding gorge. The ridges were bare of trees, which made them good places for artillery and for monitoring enemy movements at lower elevations. The dense woods would negate the advantages the Americans enjoyed in mobility, fire- power, and technology when fighting in open terrain.

At the outset of the prolonged battle, the dense forest canopy immediately caused orientation problems for the Americans. The U.S. combat units entering the forest had few maps of the woods; those they did have were in German and were difficult to interpret. From an aerial point of view, it was confusing to orient those existing maps with the ground configuration. This had an adverse effect not only on the provision of close air support but also on field artillery attempt- ing to respond to requests for fire support. The absence of distinguishable land forms in the Hürtgen Forest made it nearly impossible for spotter aircraft to orient themselves and effectively direct fire for artillery units. Bringing effective fire to bear was at times a hit-and-miss affair as the U.S. artillery had to shoot blind.

The Hürtgen Forest was not unlike other forests in Germany. As the land has been intensely cul- tivated over many centuries, so have its forests. The Germans responsible for managing the forest’s resources over the years did so in a way that would result in a maximum yield from its fir trees. Before machines were developed to remove the logs, horses performed that function. The trails, therefore, were at best covered with grass but more likely were simply soil. When the logs were dragged along the trails when the ground was hard, little damage was done to the trail surface. But in rainy spells the trails became muddy, and wheeled transport frequently got bogged down, particularly when extensive use was made of the trails. After sustained rain, the trails resembled creeks.

The true test was whether a quarter-ton truck could negotiate a trail that had turned to mud. If the trail in an inclement state could not support a quarter-ton truck, then the trail failed the test as a viable means of travel. The Hürtgen Forest, except for a few hard surface roads, failed the test and contributed significantly to logistics and communications failures. The Germans found that by felling one or two trees they could easily block a trail, and they made good use of this tactic to slow U.S. forces.

Trails were not only easy to block, but the maps often failed to show where they led. Sometimes the trails did not even show up on the map. It was easy to get lost following what appeared to be a trail leading in a desired direction but which had no specific definition when it came to leading to a military objective. The resulting confusion was compounded by the Germans’ expert use of the trails to form fields of fire for direct-fire weapons, such as the dreaded 88mm antitank artillery. American troops often could not effectively call for artillery fire using trails for orientation because of the disparate directions the trails frequently took. The best targets were villages and towns located in cleared areas.

The closely bunched trees in the Hürtgen Forest served the German defenders well. Air bursts from German mortars and artillery sent shards of wood spiking into the forest floor or into the heads and bodies of American soldiers. For this reason, American soldiers attempting to advance under such bombardment conditions were vulnerable to indirect enemy fire. While the American artillery and mortars could have the same effect on the Germans, the German defenders usually were protected by well-constructed field fortifications or concrete bunkers.

The trees also worked their misery on unprotected soldiers in tandem with the weather. A large amount of rainfall, especially during the autumn and winter action, meant that water hung in the overhead foliage only to drip constantly on soldiers without overhead cover, whether moving through the forest or in their open foxholes. American soldiers found themselves confined to waterlogged holes, which led to immersion foot, or trench foot. Casualties among soldiers who could not keep their feet dry were extremely high and the cause for much consternation among upper echelon command.

The Hürtgen Forest had other characteristics associated with the weather that affected combat operations. Dense fog and mist in the autumn and winter tended to hang in the valleys and among the trees. This hindered direct observation and posed a danger not only to patrols but also to any movement as it often proved difficult for a soldier to see more than a few feet. It was easy to get lost and disoriented walking a short distance or to accidentally stumble into an enemy patrol. Since the Germans had a better knowledge of the woods, they had a decisive advantage over the Americans when it came to moving through the forest.

In spite of the poor quality of some of the German infantry units at this stage of the war, the Germans nevertheless managed to exploit the full defensive potential of the Hürtgen Forest. They could tell from the ring of an axe being used to cut down a tree, and by the direction of the sound of the axe, just how to bring fire to bear on the GI wielding the axe. The Americans learned the hard way that when they wanted to cut down a tree to build a protected fighting position it was best to use a hand saw. American vehicles operating in the woods telegraphed their movement by their distinctive sounds. The Germans had fewer vehicles, and they used their horses effectively in the dense woods to move artillery.

The Hürtgen Forest stood at the northern end of the 390-mile West Wall. The forest was thoroughly integrated into the Germans’ forti- fication system. Even without fortifications the forest posed serious threats, but the combination proved to be a major obstacle to American forces.

The German defense of the Hürtgen Forest made use of many different techniques that stymied the American advance and compounded the effects of the forest’s natural fea- tures. The trails not only served as deadly fields of fire but also were heavily mined and booby trapped. The Americans had a difficult time overcoming the mines. The Germans placed thousands of personnel mines in about every conceivable place. They could be closely grouped and stacked one or more on top of each other. When an American soldier went to remove a mine, he had to be sure it was not booby trapped or that there was not another mine set to explode when the weight of the top mine was removed. It soon became standard operating procedure to blow up mines in place rather than try to remove them.

The Germans covered forest trails and paths with weapons fire from well-concealed fighting positions. They had a special knack for camouflage. It was not unusual for an American soldier to be standing right beside a German field fortification and not be aware of it. The German positions not only were well located to provide flanking fire, but also they provided excellent overhead protection against American artillery fire.

Because the Hürtgen Forest was part of the West Wall, there was an abundance of permanent fighting positions located throughout the forest. The Germans built elaborate concrete bunkers that were often two or three stories deep into the ground. They were perfectly camouflaged with leaves and pine needles and blended seamlessly into the surrounding landscape in a way that made them almost invisible to the American troops. They had to be reduced by infantry and engineer troops using explosive charges and small arms fire. Once captured, a bunker or concrete position had to be secured against recapture by the Germans.

German tactics took full advantage of the features of the terrain and weather while making optimum use of their defensive expertise. The Germans registered with mortars and artillery the roadblocks they had established to slow down the Americans. When the Americans fired their artillery, the Germans would fire their own behind the Americans to make the Americans think that their own artillery rounds were landing short.

German soldiers cut American telephone lines and effectively monitored the largely undisciplined American radio transmissions, which allowed them to eavesdrop on American tactical operations and activities.

If the terrain and German tactics and fortifications were not formidable enough, Hodges and his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. William B. Kean, proved themselves to be insufferable throughout the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest. Hodges, who had an abrasive personality, held the record for relieving the most corps and division commanders in Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group. He canned 10 of 13 generals. He was quick to condemn others’ shortcomings, but he took umbrage if someone insinuated that he might have contributed to the failure of one of his units. During the protracted battle he was often sick, leaving much of the combat direction to Kean.

Kean proved to be the key figure in the chain of command and ran the staff in such a way as to brook no opposition to command decisions. The rest of the staff operated as if it knew the answers to all challenges and projected a negative attitude to First Army units, which manifested itself in a blind stubbornness and ultimately resulted in heavy casualties. The First Army staff was the least effective of Bradley’s three armies.

Hodges’ First Army had three corps, but only two fought in the Hürtgen Forest. One was Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’ VII Corps, and the other was Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow’s V Corps. Collins’ VII Corps comprised the 4th Cavalry Group, 1st Infantry Division, 9th Infantry Divi- sion, and the 3rd Armored Division. Gerow’s V Corps was composed of the 102nd Cavalry Group, 4th Infantry Division, 28th Infantry Division, and the 5th Armored Division. Collins’ VII corps would spearhead the attack into the Hürtgen, and Gerow’s V Corps would advance to the south to cover Collins’ right flank.

Three factors in particular would contribute to the agonizingly slow progress that Hodges’ First Army would make through the Hürtgen Forest. The first factor was the dense nature of the woods, which slowed the American advance to a crawl. The second factor was the Germans’ stubborn defense. The third factor was First Army’s command shortcomings and the adverse effect these problems had on frontline combat units.

The initial, relatively brief encounters in the dark forest experienced by the U.S. 3rd Armored Division and the U.S. 1st Infantry Division were also experienced during Maj. Gen. Louis A. Craig’s 9th Infantry Division’s penetration of the West Wall on September 13. Craig’s division would be the first of several to experience the Hürtgen Forest’s death grip.

The 1st Battalion of the division’s 39th Infantry Regiment crossed the German border from Belgium almost unopposed into the town of Lammersdorf on September 14. Lammersdorf was situated just outside the southeast corner of the Hürtgen Forest abreast of the West Wall fortifications. Hardly had the U.S. infantrymen advanced beyond the town when the German 98th Infantry Division sprang into action. German gunners inside pillboxes poured heavy fire into the advancing Americans, pinning them down.

This marked the beginning of the battle. The battle began with tedious small unit combat against a determined but understrength enemy. By September 18, the Americans had managed to carve only a 11/2-mile-wide path through the German fortifications at the forest’s edge. Frequent rain and thick cloud cover limited the number of close air support missions that U.S. ground attack aircraft could fly.

The quality of the German forces the 9th Infantry Division faced offered the Americans some degree of solace, though. Colonel Karl Roesler’s 89th Infantry Division, which by that time was composed of only two grenadier regiments, was badly depleted in manpower. Created in January 1944 with conscripts from the Replacement Army, the division had suffered heavy losses in Normandy. By September, one of its two remaining regiments was almost nonexistent as a result of attrition, and the other had only 350 men. Roesler had scraped together his artillerymen, engineers, and service troops and put them on the front line. The German high command had reinforced his division with a battalion of reservists, three battalions of Luftwaffe ground protection troops, and a battalion of 450 Russians pressed into German service.

Deployed to the north on Roesler’s right flank across the German LXXIV Corps boundary was the German 9th Panzer Division. The panzer division also was badly understrength. It had 2,500 grenadiers, 200 machine guns, and 13 Panther tanks. The Germans’ best hope lay in the anticipated arrival from the Eastern Front of Colonel Gerhard Engel’s 12th Infantry Division. The division had 14,800 men organized into three infantry regiments, each of which had two battalions. It also had 12 batteries of artillery.

The lead elements of the 12th Infantry Divi- sion began arriving in the northern part of the Hürtgen Forest on September 16. Engel’s troops initially engaged elements of Rose’s U.S. 3rd Armored Division and the 47th Infantry Regiment.

The arrival of Engel’s troops compelled Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, the American VII Corps commander, to direct Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division, Rose’s 3rd Armored Division, and Craig’s 9th Infantry Division to consolidate their positions by shortening their lines. Collins then ordered the 9th Infantry Division, after a brief pause, to begin clearing the Hürtgen Forest to remove the threat the Germans there posed to his right flank.

The Schwammenauel and Urft dams, known as the Roer dams, were becoming increasingly important objectives to Hodges’ First Army. The Roer dams had only belatedly been gaining recognition as justification for a continued advance. Bradley, Hodges, and Collins agreed that the Americans needed to seize the dams to prevent the possibility of the Germans releasing the water and flooding the Roer Valley. If that occurred, millions of gallons of water would keep the river at flood stage for weeks, inundating the entire valley. The Roer River at flood stage might delay the passage of American forces for several weeks. When Collins ordered the 9th Infantry Division into the forest in Sep- tember, the need to capture the dams had not been considered a critical intermediate objective in First Army’s advance to the Rhine River.

To accomplish the forest-clearing mission, arrayed north to south in the Hürtgen Forest were the 9th Infantry Division’s 47th, 60th, and 39th Infantry Regiments. Beginning on September 19, the division sought to capture the key crossroads town of Schmidt on the eastern edge of the forest near the dams.

Schmidt, which was located just over a mile west of the dams, lay behind the West Wall in open terrain. Its seizure was essential to the capture of the dams. At that point, the progress of the U.S. infantry began to be measured in yards rather than miles.

American close air support was limited. Fog and mist at ground level obscured observation even if the skies above were clear. These conditions precluded effective support. Within the forest, tanks and tank destroyers had difficulty maneuvering and bringing their guns to bear. By the close of September, the 60th Infantry Regi- ment had bludgeoned its way aimlessly through a morass, almost reaching the Germeter–Hürtgen–Kleinau Road in the forest. The 39th Infantry Regiment had reached the Lammers- dorf–Germeter Road on the 60th Infantry Regiment’s south flank. But the Germans still held Schmidt.

By October 6, the 9th Infantry Division held a nine-mile front. Before the division could capture Schmidt, it had to take other villages. The 39th Infantry on the left and the 60th on the right received orders to capture the villages of Germeter and Vossenack, cross the Kall River valley, and advance through the hamlet of Kommerscheidt to Schmidt. A narrow, twisting path known as the Kall Trail led south from Vossenack through the woods to the Kall gorge. Beyond the gorge lay Kommerscheidt and Schmidt practically adjacent to each other.

It was a tall order given the fierce German resistance. General Hans Schmidt’s 5,000-strong 275th Infantry Division opposed the two American regiments. Although his division was not at full strength, its troops nevertheless had constructed log bunkers, foxholes, and roadblocks. They also had laid mines, strung barbed wire, and established interlocking fields of fire.

On October 6, the two U.S. regiments attacked. They immediately ran into tenacious resistance. Although advance elements pushed through the pillboxes of the West Wall, progress was extremely slow.U.S.tanks and tank destroyers arrived two days later to assist the infantry. Thearmor’sextra weight resulted in a limited penetration of the West Wall.

The 1,200-strong German battle group known as Regiment Wegelein, which was named after its commander, Colonel Wolfgang Wegelein, began moving south toward the Hürtgen on October 11 to assist the 275th Division. The following morning, Wegelein’s men, who were well armed with submachine guns, machine guns, and mortars, attacked the northern flank of the 39th Infantry Regiment at the village of Wittscheidt. The Americans held onto the village, but the counterattack forced them to halt short of Schmidt and consolidate their positions.

Over the course of the next two weeks, the tired, disillusioned, and bedraggled U.S. soldiers were forced to withstand ever worsening weather, constant enemy patrols, and withering artillery fire. On October 25, the 9th Infantry Division, except for the 47th Infantry Regiment, was allowed to pull out of the front line for rest and rehabilitation.

In less than four weeks, the 9th Infantry Division had suffered 4,500 casualties. Moving up to replace the 9th Infantry Division was Maj. Gen. Norman D. “Dutch” Cota’s 28th Infantry Division. It was known alternately as the Keystone Division or Bloody Bucket Division. Hodges and his staff remained firmly convinced that the best route to the Roer dams was through Schmidt. Hodges ordered Dutch Cota to send all three of his regiments against the Germans. He reinforced Cota with three engineer combat battalions, a battalion of towed tank destroyers, and a chemical mortar battalion.

As October drew to a close, the Germans began earnestly preparing for “Wacht am Rhein,” the German codename for the Ardennes counteroffensive. The preparations involved the withdrawal and reconstitution of forces, some of which were elite panzer formations, that had been deployed near the Hürtgen Forest. Because of this, the fighting against the Americans fell to third-class German infantry divisions.

The experience of Dutch Cota’s troops is summarized in the division’s combat chronicle. “The 28th smashed into the Hürtgen Forest [on] 2 November 1944, and in the savage seesaw battle which followed, Vossenack and Schmidt changed hands several times.” Cota deployed the 109th Infantry Regiment on the left, the 112th Infantry Regiment in the center, and the 110th Infantry Regiment on the right.

The regiments advanced in unison on November 2. Lt. Col. Carl Peterson’s 112th Infantry Regiment in the center initially had the most success. Backed by M4 Sherman tanks, the GIs man- aged to fight their way into Vossenack. German grenadiers armed with panzerfausts knocked out five Shermans, but at least the Americans had something to show for the destroyed tanks. The following day, two battalions of the 112th crossed the Kall River. The 3rd Battalion, 112th Regiment fought its way through Kommerscheidt and entered Schmidt. The Americans caught the German garrison in Schmidt by surprise. By nightfall the town was squarely in the hands of three American rifle companies and a weapons platoon. Exhausted from the previous days’ march, they decided not to send out any patrols that night.

But the Germans launched a vicious counterattack. The advancing enemy wiped out the 3rd Battalion. The Germans also retook Kommerscheidt before the counter-attack ground to a halt.

By the end of the first week in November, only Vossenack was still in American hands. After the fighting on the Kall Trail ended, the regiment held only the western slope of the gorge. Cota’s 28th Infantry Division had suffered the same heavy casualties that the 9th Infantry Division had suffered.

As the 28th Infantry Division was pulled out of line for rehabilitation on November 16, First Army prepared to make another major push to reach the Roer River. By then three U.S. infantry divisions were in the Hürtgen Forest. They were deployed north to south as follows: 1st, 4th, and 8th. The primary responsibility for clearing the forest at that point fell to Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton’s 4th Infantry Division. Barton had orders to clear the Germans from the forest and then proceed northeast to the Roer River at Dueren.

Combat Command R (CCR) of the 5th Armored Division moved up to assist Barton’s division in capturing the village of Hürtgen, which lay north of Vossenack. Schmidt’s grenadiers braced for the attack of a fresh American division. Barton was promised air support. Despite inclement weather at Allied bomber bases in France and England, the bombers conducted bombing runs against the German positions in the Hürtgen in mid-November. Unfortunately, the bombs had minimal effect on the German fortifications. The Americans also unleashed the fire of nearly 700 artillery pieces against the German positions.

The 4th Infantry Division soon became yet another victim of the forest. Its 12th Infantry Regiment suffered heavy casualties in nine days of bitter fighting. Despite the heavy casualties incurred, the regiment seized control of key roads in the forest on November 16 that allowed CCR’s tanks and tank destroyers to launch a major assault against German forces in the village of Hürtgen. But the Germans mauled the 12th Infantry Regiment, which by November 21 had suffered 1,600 casualties. Adjacent U.S. infantry regiments had no better luck in the forest as they struggled to clear the stubborn German resistance.

“As early as mid-September, the 9th Division had demonstrated that to send widely separated columns through an obstacle was to invite disaster,” states the U.S. Army’s official history. “Yet on a second occasion in October the 9th Division had tried the same thing and in early November the 28th Division had followed suit. Now the 4th Division was to pursue the same pattern.”

In a number of actions in the eastern sector of the forest both the 8th and 22nd Infantry Regiments of the 4th Infantry Division strug- gled forward having to confront not only inclement weather and stiff German resistance, but also supply difficulties. By December 2, the regiments were on the verge of finally breaking out of the forest when they halted. But in doing so, they had suffered enormous losses.

To the north, Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division, after severe fighting in the northwest portion of the forest, initially made enough progress to give higher headquarters some encouragement, but the intractable weather combined with stubborn German resistance kept the division from advancing out of the forest to drive to the Roer River.

One of the 1st Infantry Division’s key objectives was the village of Heistern. With the assistance of artillery and tank fire, a battalion of the division’s 18th Infantry Regiment succeeded in getting into the village the night of November 21. That night Colonel Josef Kimbacher, commander of the 104th Regi- ment of the 47th Volksgrenadier Division, led his troops in a counterattack. The Americans repulsed the attack and took 120 prisoners including Kimbacher.

Vicious fighting continued as both sides fought to control key terrain. The Germans launched an attack to retake Hill 203, and once they captured it they fought tenaciously to hold it because it afforded excellent observation over the surrounding terrain. The U.S. 18th Infantry Regiment drove the Germans from Hill 203 on November 24.

Meanwhile, the 8th Infantry Division, which was assigned to V Corps, with the 5th Armored Division’s CCR in support, engaged the Germans. The 121st Infantry Regiment engaged four understrength battalions of the 275th Infantry Division in the mud, fog, and rain for control of the villages of Hürtgen, Kleinau, Brandenberg, and Bergstein.

By December 9, American M4 Sherman tanks had swept through the villages. The attached 2nd Ranger Battalion advanced from Bergstein and captured the excellent observation site of Hill 400.5, more familiarly known as Castle Hill. But the Germans immediately counterattacked and retook it. The 2nd Ranger Battalion suffered 25 percent casualties. Overall, the late November and early December push resulted in more than 1,200 U.S. casualties.

A hiatus occurred at that point as both sides concentrated on the Ardennes campaign. During that time, the 83rd Infantry Division relieved the battered 4th Infantry Division; however, the 1st and 8th Infantry Divisions remained in place. In two months of sustained fighting in the Hürtgen Forest, five U.S. infantry divisions (along with a ranger battalion and an armored combat command) had suffered severe casualties. Losses amounted to approximately 5,000 men per division. The main objective of the battle, the Roer dams, would remain in German hands until February 1945.

Even at the outset of the Battle of the Bulge, Hodges remained fixated on capturing the Roer dams. He even launched yet another push to capture them. But when it was realized that the German counteroffensive in the Ardennes threatened the entire Western Front, Bradley compelled Hodges to switch to a defensive position. From mid-December to January 31, 1945, the action in the Hürtgen Forest was limited to local patrolling.

On February 5, Maj. Gen. James M. Gavin’s 82nd Airborne Division and the 78th Infantry Division launched an attack from the western edge of the Hürtgen Forest to capture the Urft and Schwammenauel Dams on the Roer River. The paratroopers were shocked at what they saw as they took up their position on the Kall Trail to protect engineers clearing mines. “Immobile tanks and trucks and the bodies of dead American soldiers were everywhere,” said Lieutenant John Cobb of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. “The snow and cold had preserved the dead and they looked so life like it gave one a very eerie feeling.”

Gavin established his command post in the Hürtgen Forest and saw firsthand the nightmarish conditions through which the Americans had suffered 33,000 casualties. “All along the sides of the trail there were many, many dead bodies, cadavers that had just emerged from the winter snow,” wrote Gavin. “Their gangrenous, broken, and torn bodies were rigid and grotesque, some of them with arms skyward, seemingly in sup- plication.” Such was the harvest of death in the Hürtgen Forest.

With orders to capture Kommerscheidt and Schmidt, the 82nd Airborne fought its way down the trail, across open terrain to Kommerscheidt, and continued on to Schmidt. The next step was to seize the two dams and prevent the Germans from flooding the area below the dams. The capture of the dams came several months too late, though, in some respects. “Had we secured them early in November [1944] and pushed across the Roer, the enemy would never have dared coun- terattack us in the Ardennes,” wrote Bradley.

The belated task of capturing the Schwammenauel Dam was to be undertaken by troops from the 309th Infantry Regiment of the 78th Infantry Division. They approached the dam from the south while the 82nd Airborne Division put pressure on the enemy from its positions at Schmidt. Under German artillery and mortar fire on the night of February 9, American engineers and riflemen clambered atop the 170-foot-high dam to find it intact with no explosives attached. The Germans, however, had used another method to thwart the Americans. The American engineers soon discovered that the gate house, power room, and discharge valves controlling the flow of water from the dam had been thoroughly smashed. An immense of amount of water was already rushing downstream. Furthermore, the Germans had dynamited an outlet valve on the smaller upstream Urft Dam, which released additional water into the basin of the Schwammenauel reser- voir. The Battle of the Hürtgen was over, but by flooding the Roer River the Germans delayed the Americans from crossing it for two weeks.

The Hürtgen Forest debacle was a costly one for the Americans in more ways than just failing to accomplish a timely capture of the two dams. From the beginning, the vague objectives assigned to the American divisions committed to the Hürtgen Forest resulted in heavy casualties not only in personnel but also in weapons and equipment. More than 8,000 First Army men suffered from combat exhaustion, and another 23,000 men were killed, wounded, missing, or captured. Multiple factors, including inclement weather, rough terrain, and enemy counterattacks, together with a corrosive command environment, combined to take a heavy toll on the American forces involved.

“In retrospect, it was a battle that should not have been fought,” wrote Gavin. The battle for the Hürtgen Forest stands as one of the major mistakes of the war in Europe. On the whole, the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest produced heavy casualties for very little strategic benefit.

I can’t help but think of these similar conditions that Roman Legions surely encountered in their operations in those dark forests of Germania.

My great uncle was killed in this battle. It’s a Great article