By Kevin Morrow

Black puffs from flak bursts began blossoming in the air around Lieutenant Tom Oliver’s Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber high over the town of Bor, Yugoslavia. Suddenly, he felt a violent jolt. The plane had taken a hit.

Enemy flak had already eviscerated engines three and four over the target, the railroad yards at Campina, Romania. Now, engine two was engulfed in flames. Oliver and his crew would never make it back to the 756th Bomber Squadron’s base in Italy with one engine. Only one option remained.

Oliver hit the alarm button. “Bail out! Bail out!” he cried over the bomber’s intercom system.

He looked out the window to check engine two one more time: still burning. Looking behind him, he saw John Thibodeau, the navigator and last crewman left, motioning for Oliver to come. Oliver waved to him to get out. He didn’t want anyone in his way when he let go of the wheel to sprint for the hatches. Minutes later, the young pilot was tumbling earthward by parachute, watching helplessly as the plane slammed into the ground below, exploding in a massive fireball.

When Oliver touched ground, he landed almost on top of a Serb peasant family seated at a picnic table eating their lunch. The friendly Serbs offered Oliver the eyeballs from a sheep’s head. Oliver declined, but he did accept a glass of wine instead.

Ten minutes later, two men on horseback wearing military jackets, caps, and guns slung over their shoulders came by and motioned for Oliver to mount a horse and accompany them. As Oliver rode off with them, he had no idea that his sojourn behind enemy lines would last 96 days, much less that the U.S. Army Air Forces and America’s covert operations organization, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), would rescue him and hundreds like him in one of the largest and most daring air-rescue operations of World War II.

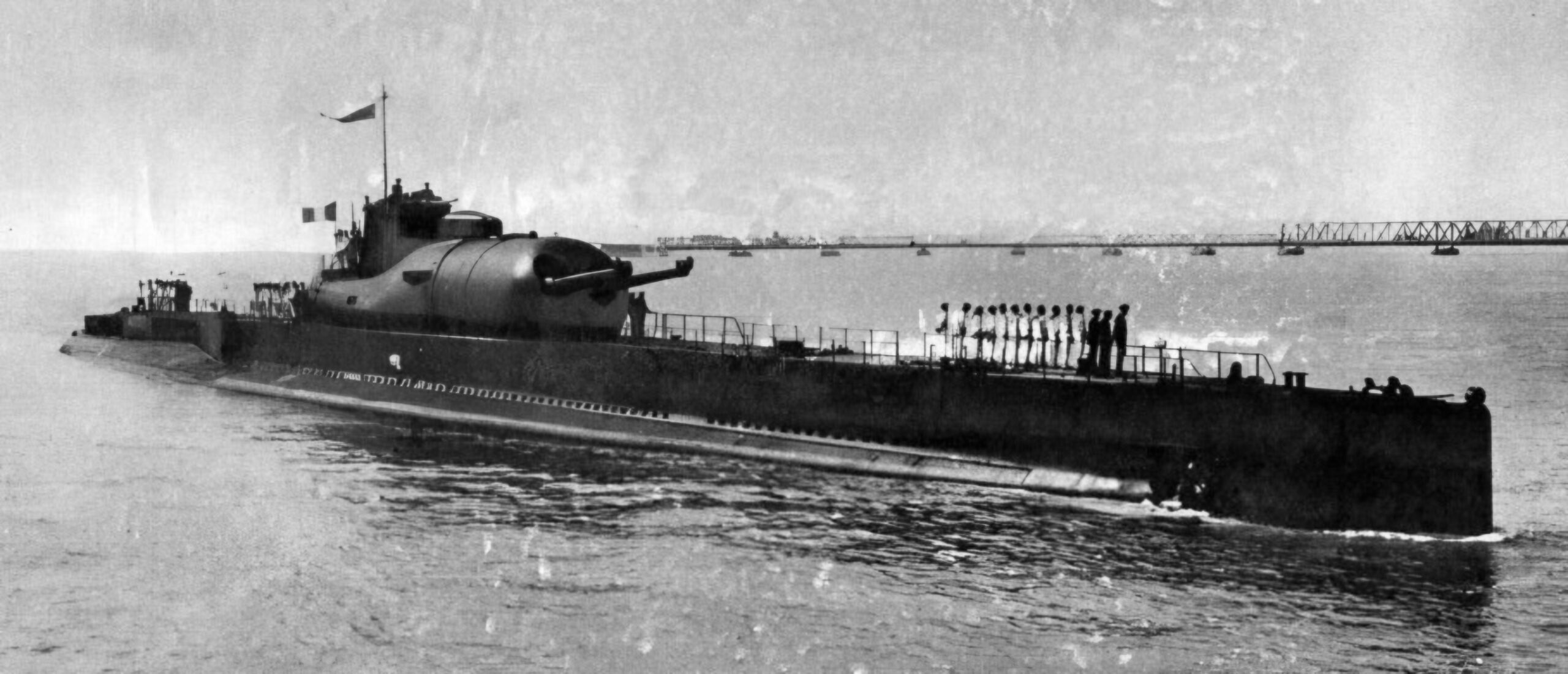

Oliver and his crew were frontline warriors in the so-called “oil campaign” of 1944, an attempt by Anglo-American air forces to destroy Nazi Germany’s vast European network of fuel resources. One particularly vital target was the huge complex of oil refineries at Ploesti, Romania, which provided Germany 35 percent of its petroleum supply. In April, American bombers began blasting it nonstop, completely halting oil production by August 24. The bombing campaign ended in success, but Ploesti’s defenses—the swarms of German fighters and massive rings of radar-directed antiaircraft guns—exacted a terrible price on the victors: 350 bombers lost, their crews killed, captured, or missing.

Hundreds of the missing airmen shot down between Ploesti and American air bases in Italy bailed out over eastern, Nazi-occupied Serbia, an area patrolled by a guerrilla resistance army called the Chetniks. When the Chetnik commander, General Drazha Mihailovich, became aware of the airmen coming down in his territory, he ordered his men to begin gathering them for evacuation back to the Allies.

Some of the American airmen treated their Chetnik rescuers with suspicion at first because rumor had it that the Chetniks routinely turned over downed Allied airmen to the Germans. These wild men of the mountains even fancied cutting the ears off of their prisoners, if the stories were true.

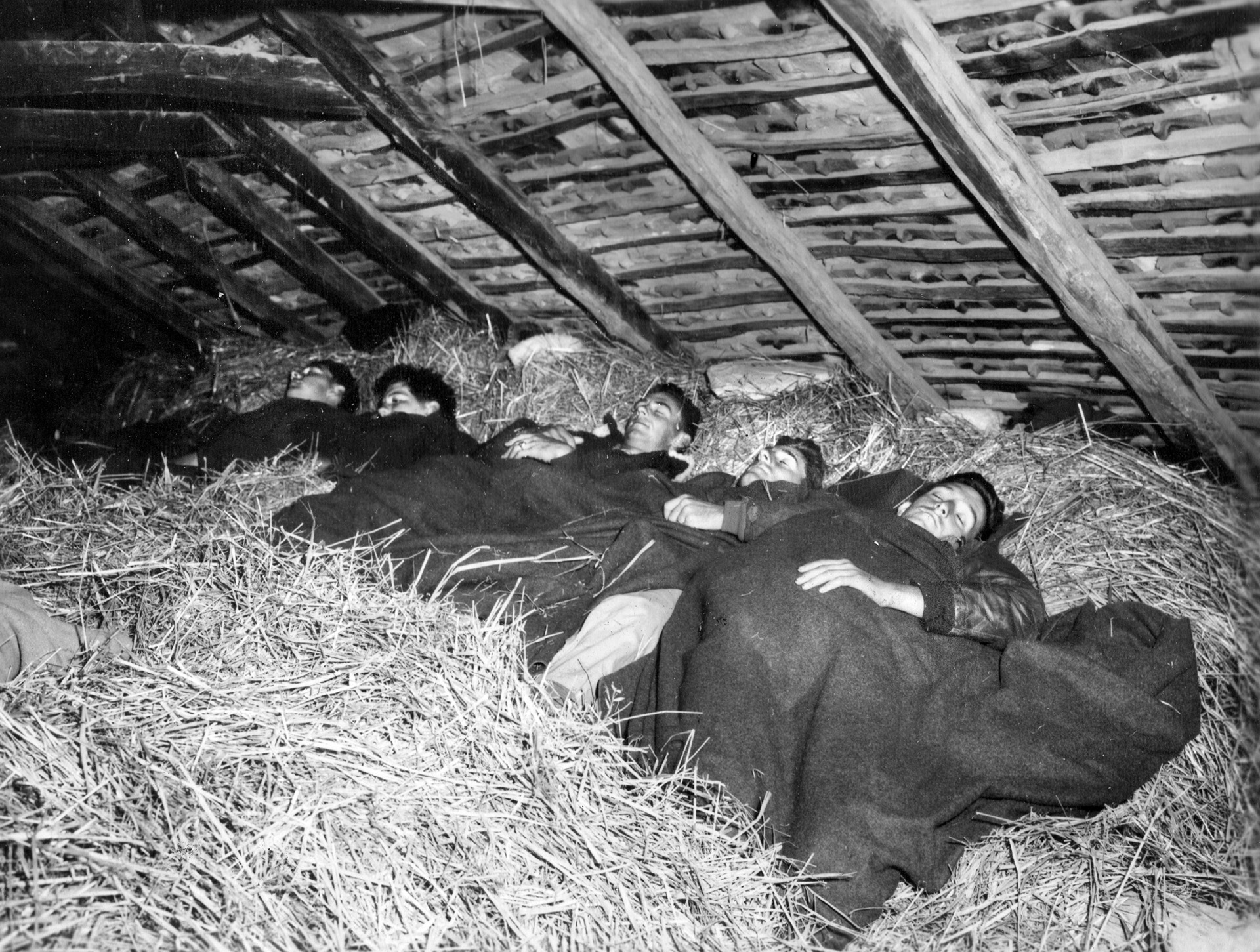

The reality on the ground looked quite different. Responding to Mihailovich’s appeal for help, the Serb peasants who lived in the area around the Chetnik base in the mountain town of Pranjani willingly hid the airmen in their own homes. Even after the Germans demanded the surrender of the airmen who had been spotted bailing out, threatening reprisals for disobedience, the Serbs refused to give them up.

Mihailovich’s goal was to return the men to the Allies, but despite his good intentions several serious difficulties would stand in the way of getting them back home again. For starters, just sneaking into Serbia past the Germans to reach the airmen in their rugged mountain sanctuary and then safely spiriting them back out would itself take a logistical miracle. Surmounting the massive political obstacles to forging an operational Allied-Chetnik partnership, though, ultimately proved even harder than the logistics, and for several reasons.

After Yugoslavia capitulated to a German invasion force in April 1941, the Royal Yugoslav Army’s Chetnik units fled to the mountains to continue the fight against their occupiers. One large coalition of Chetnik bands led by then-Yugoslav Army Colonel Drazha Mihailovich began attacking Axis troops in the summer of 1941, which, in the beginning, generated favorable press, military assistance, and support from Allied countries. In response, Axis forces hit back with murderous reprisals against Serb civilians. This led Mihailovich to hit the brakes on active, armed Chetnik resistance in hopes of sustaining his army in the field to aid the future Allied liberation of Yugoslavia.

A rival communist guerrilla force known as the Partisans, by contrast, enthusiastically carried out armed confrontation with the enemy, gaining favorable attention from the Allies. This, plus the Chetniks’ inaction, their distraction with the growing Partisan-Chetnik civil war, and some relatively credible allegations of Chetnik collaboration with the Germans and Italians eventually sank Allied faith in Mihailovich’s commitment to the fight. At the end of 1943, the Allies decided to formally drop the Chetniks and shift official military support to the Partisans.

Despite now being persona non grata with his former allies, Mihailovich began attempting to alert them about the presence of the airmen using a variety of communication channels. He had his men send messages over a British radio link that the Chetniks had formerly used to communicate with Allied leaders, and he also sent word to the Yugoslav government-in-exile in Cairo. The Yugoslav government forwarded these messages to the Yugoslav ambassador to the U.S. in Washington, D.C., Konstantin Fotich, who in turn informed the U.S. War Department. The American government, however, took no action.

By a strange twist of fate, word of the airmen’s plight reached the ears of a Serb employee of the Yugoslav embassy in Washington, Mirjana Vujnovich. She immediately wrote her husband, Captain George Vujnovich, chief of OSS operations at its field station in Bari, Italy.

She asked: had he heard of this, too? George Vujnovich had not. A round of inquiries in his sphere of activity revealed that the Americans were quite aware of the situation, but no rescue mission was planned because of Mihailovich’s continuing black sheep status. Convinced that his wife’s information was correct, Vujnovich began putting together a plan to get the men out. A son of Serb immigrants to America and a former refugee (he had himself fled Yugoslavia during the 1941 invasion), Vujnovich felt tremendous sympathy for both the downed airmen and their protectors in Serbia, but he had no illusions that the Allied leadership felt the same way.

Anti-Mihailovich sentiment reigned within the SOE (the Special Operations Executive, Britain’s OSS), which Vujnovich and other Chetnik supporters suspected sprang from a smear campaign conducted by communist-leaning Partisan sympathizers within the organization. It came as no surprise, then, when the British bitterly opposed Vujnovich’s plan, and as the SOE had formal jurisdictional control over covert operations in the Balkans, it quickly became clear that shepherding Vujnovich’s plan through to approval would be an uphill climb.

The somewhat less hostile but still-skeptical American leadership speculated that Mihailovich, in aiding the airmen, hoped to use them as trophies of his loyalty to the Allied cause. On the other hand, the fraught relations within the Anglo-American intelligence community, which was riven by suspicion, uncooperativeness and occasional outright antagonism, tilted the political balance in Vujnovich’s favor.

In the end, this determined opposition convinced the OSS to go all the way to the top to get the green light. In a meeting with U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt in early July 1944, the famously straight-talking head of the OSS, Maj. Gen. William “Wild Bill” Donovan, reputedly summed up his case for the operation, now codenamed Halyard, by telling Roosevelt, “Screw the British! Let’s get our boys out!”

Roosevelt agreed, and the wheels started to turn at last. On July 14, General Ira Eaker, U.S. commander of the Mediterranean Allied Air Force, signed orders creating a new covert mission organization, the Air Corps Rescue Unit (ACRU), which was to be supported by air resources of the Fifteenth Air Force.

Planning began in earnest with the formation of an OSS team to be airdropped into Serbia. The leader of the Halyard team, now officially designated ACRU-1, would be OSS officer Lieutenant George Musulin.

Musulin had served in Yugoslavia with an Allied intelligence and training mission attached to Mihailovich’s I Chetnik Corps from October 1943 to late May 1944. He had witnessed himself the plight of the downed airmen, 40 of whom accompanied the mission on its evacuation back to Italy. Back at Bari, Musulin became furious after learning that no evacuation mechanism for downed airmen existed in Chetnik areas as was the case in Partisan territory, a result of the continuing Allied mistrust of the Chetniks. Convinced of their innocence, Musulin offered to parachute back into Serbia to gather evidence of the Chetniks’ loyalty, but his superiors refused the request.

Now, in July, the time had come to go back. Another veteran of OSS covert operations in Yugoslavia, Navy Radio Specialist 1st Class Arthur Jibilian, would serve as Halyard’s radio man, and Army Master Sergeant Mike Rajacich would be Musulin’s second-in-command. All three men spoke Serbo-Croatian.

As the Halyard team quickly ramped up their plans and gathered needed equipment, the planners began to seriously assess the risks the men would be facing. Just communicating their intentions to the Chetniks would be tricky, as the Allies had cut off all radio links to Mihailovich except for one indirect, non-secured channel. Even if they could raise the Chetniks on this radio link, the OSS worried, the Germans would surely be listening in, threatening operational security. With the military situation in Serbia so fluid, the designated drop zone could also fall into German hands unexpectedly, and as Musulin was aware, the Germans often lit flares on the ground to attract Allied planes flying overhead.

Worse still, the Air Force would have to send its C-47 transport planes unarmed into a landing zone just minutes by air from nearby Luftwaffe airfields. This would leave the C-47 crews utterly defenseless to enemy air attack, so the Air Force opted for nighttime landings, which would be dangerous even if the one available landing strip near Pranjani was usable, which it definitely was not.

First things—safely inserting the three-man Halyard team—had to come first, and once the team reached Pranjani, Halyard commanders hoped they would be able to iron out the potential roadblocks to pulling off the first airlift.

When plans were set, the British alerted the Chetniks to expect the arrival of the Halyard team between the dates of July 15 and 20 at preset coordinates. Numerous snafus in attempted air jumps over the assigned drop zone, though, delayed the Halyard team’s infiltration long past their original insertion date.

On July 8, bad weather canceled the drop. On July 19, the team flew over the drop zone, but in the absence of ground signals at the drop zone below, they decided to turn back to their launch point, fearing a trap. On their third attempt on July 25, their transport plane got pelted with heavy antiaircraft fire just inside Yugoslav airspace. At the drop zone, once again, there was no signal. The following night, July 26, the red signal lights down below didn’t correspond to the signal they were expecting. Suddenly, a blinding glare from an airborne German signal flare lit the plane up, followed by small-arms fire. They were obviously in the wrong place, so the plane immediately turned around and headed back to Italy. Still another try aborted when Musulin, now suspecting deliberate sabotage by the British, found that the drop coordinates given to the pilot lay in Partisan territory.

The last straw came on the sixth try when the mission pilot tried to drop them over an area where a battle was in progress. That did it. As soon as the team got back to Bari, Musulin demanded and subsequently got from Vujnovich an American plane, crew, and jumpmaster.

As the operation was coming together, the airmen, who had been waiting in Serbia for weeks, remained largely in the dark about contemplated rescue preparations. Throughout the spring and early summer, they had been content to wait for the Air Force to come get them, but with each passing month the need for action had grown increasingly urgent. Local food stocks available for feeding their swelling ranks were dwindling, some airmen were sick or suffering from combat wounds, and they feared that their luck in concealing themselves from the Germans would eventually run out. They had heard about Chetnik efforts to contact Allied authorities, but the lack of response led some of them to conclude that their only hope of rescue might lie in reaching out on their own to the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy.

The airmen began discussing the possibility of sending a radio message to alert the Air Force to their condition and location, but some judged this to be too dangerous. Sending a message over an open radio channel as suggested might alert the Germans to their presence and provoke a swift and deadly German response. Others, though, were betting that the Germans, who were taking a beating on two fronts, had not kept their best troops in Yugoslavia and that these did not want to take the risks involved in trying to capture them. The ranking officers among the airmen ultimately decided to take the gamble, so in late July the Chetniks loaned them a radio salvaged from one of the many wrecked U.S. bombers the Germans had shot down in the neighborhood.

The first short SOS message the airmen sent out over a rarely used, unsecured radio frequency—every few hours for two days—went unanswered at first, but then the Air Force answered back with a string of wary, suspicious questions. To convince the receivers on the other end that they were who they said they were, Lieutenant Tom Oliver devised a code that referred to painted insignia on planes, details of the officer’s club at his airbase, and other things that only a very few people would know.

“Mudcat driver to CO APO520. 150 Yanks in Yugo, some sick,” the new SOS message read. “Shoot us workhorses. Our challenge: first letter of bombardier’s name, color of Banana Nose’s scarf. Your authenticator: last letter of chief lug’s name, color of fist on wall. Must refer to shark squadron, 459th BG for decoding. Signed, TKO, Flat Rat 4 in lug order.” Oliver added a jumble of numbers at the end of the message that cleverly mixed the longitude and latitude of their position (which he had plotted using captured German maps of Serbia) with the serial numbers of several members of his fellow airmen in Serbia.

A Royal Air Force radio operator in Italy received this new, cryptic message, and he immediately forwarded it to Fifteenth Air Force headquarters in Bari, where 756th Bomber Squadron intelligence officers decrypted the message. Not only did the Americans now have the precise coordinates where the airmen were waiting, but for the first time they realized that the flight crews who had gone down in that area were gathered in one place.

On the other end of the radio link, silence followed for several days. Finally, the Air Force replied: “Prepare reception for 31 July or first clear night following.”

No plane came on the 31st or the following day, August 1. After six failed starts, the team members were by now “nervous wrecks,” in Musulin’s words, but dogged persistence finally paid off on the seventh and final jump attempt on the night of August 2.

Gathered at the drop zone, the waiting airmen and their Chetnik protectors caught the sound of an approaching plane. They crouched in the bushes, waiting tensely to see if it was German or American as the plane circled the drop zone for 10 minutes, then flew low over the ground. Then, the men caught sight of the white U.S. Air Force star under the wings. “With one voice, the men let out a yell,” Lieutenant Richard Felman, one of the leaders of the airmen, recalled. “It was just like [Babe] Ruth hitting a homer with the bases loaded in the World Series.”

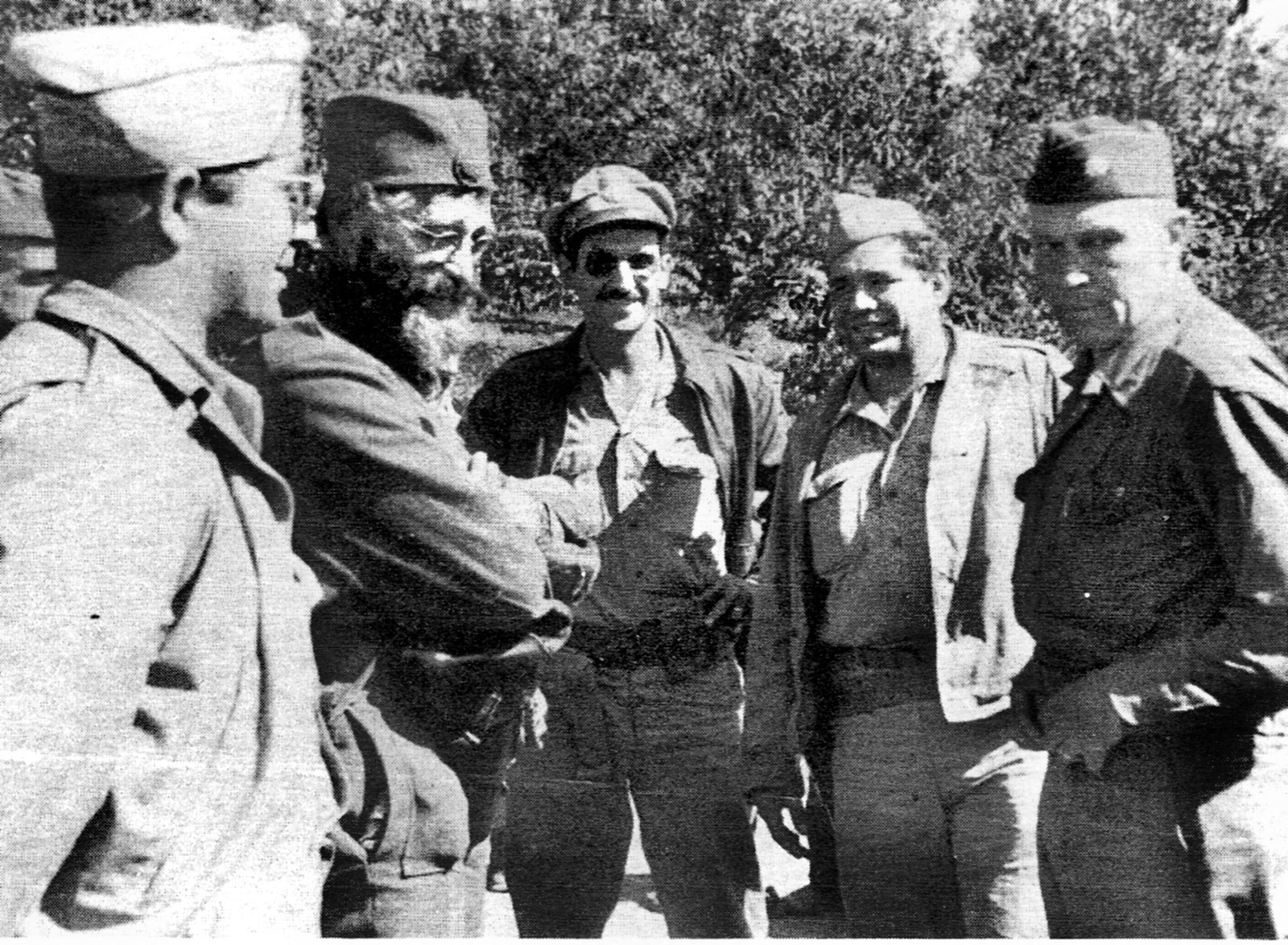

Musulin, Rajacich, and Jibilian had accidentally missed the drop zone by two miles. As they approached the drop zone on foot, Felman heard a commotion in the darkness, Chetniks shouting and cheering, “Captain George, Captain George!” Moments later, the Halyard team walked up at the head of a crowd of exulting Serb civilians. Musulin stretched out a hand to Felman, and said, “I’m Lt. George Musulin.”

Shortly after dawn the next day, Musulin got down to business, starting with a survey of American personnel needing evacuation. The senior American officers among the airmen informed him that approximately 250 men in the vicinity were quartered in small groups in the homes of local Chetniks dispersed in a 10-mile radius. Twenty-six of the airmen were wounded or injured, so Musulin set up a small hospital with the medical supplies the team had brought. Several of the airmen were barefoot and clothed in a motley mix of Air Force and Serbian peasant dress. Many had grown long hair and beards and had begun to resemble their Chetnik hosts in appearance.

Next, the commander of the I Chetnik Corps troops protecting Pranjani, Captain Zvonko Vuchkovich, briefed Musulin on local security conditions. Not too far away were several German troop garrisons: 4,500 troops 12 miles to the south at Chachak; 250 at a garrison five miles from the airstrip; and yet another garrison at Gorni Milanovic, 20 miles east. Thirty miles south, there was also a Luftwaffe airfield at Kraljevo. The only things standing between the vulnerable airmen and the enemy were their remote location high in the mountains, the support of the local Serb civilian population, and the double ring of defenses and roadblocks manned by Chetnik soldiers surrounding Pranjani.

Now the Halyard team faced the most urgent and difficult task of all, making the Chetnik force’s existing airstrip usable. The airstrip had been gouged out of a narrow plateau high up in the mountains; it was bordered by dense woods on one side and a steep dropoff on the other. It ran only 1,800 feet, too short for a C-47 to land with a comfortable margin of error, and this made it unusable. Somehow, the Halyard team would have to lengthen the airstrip.

The 250 airmen, joined by 300 Serb villagers and Chetnik soldiers equipped with 60 oxcarts and simple farm implements, got cracking. Cutting down trees, hauling rocks away with bare hands, hauling gravel, and tamping down the earth with their feet, the work crews labored for almost a week, stopping only to rush into the woods for cover when German warplanes approached.

Musulin pushed the laborers as fast as they could go, and by August 8, the field was ready. Jibilian radioed Bari that evacuations could start the following night, August 9.

All had gone well, except for a brief scare that almost derailed the whole operation a few hours before the first planes were scheduled to arrive. While Rajacich and Jibilian were laying out the flare pots to mark the airstrip at 6 pm on August 9, three German planes—a Stuka dive bomber, a Ju-52, and another plane marked with the Red Cross emblem—buzzed the landing field, circled, and then headed back the way they came. The horror-struck Halyard team feared the worst—that the Germans had discovered the impending operation and were sending troops to capture or kill the airmen or shoot down the incoming C-47s, which were already in the air and couldn’t be recalled.

The men felt helpless in the face of impending disaster. Nonetheless, they had one ace in the hole that might allow them to get the drop on a German attack: a secret phone line to a Chetnik source in the nearby German garrison town of Gorni Milanovac. Unusual activity in Gorni Milanovac would constitute a sign of brewing trouble, but all was reported quiet in the town.

With that behind them, the first 72 designated evacuees, their fellow airmen, the Halyard team, and dozens of Serb villagers and Chetniks gathered at the airstrip after dark to await the first planes. All were excited and optimistic, but tense and anxious as well.

The first men to fly out would include the sick and wounded, and the passenger capacity of each plane was limited to 12 in order to keep the weight down because of the danger of the short airstrip. To help with the weight requirements, the Halyard team had asked the Air Force to strip each transport plane down and carry only half a tank of gas on each flight, just enough to last the round trip between Pranjani and Italy.

Cheers erupted when, at 11 pm, the crowd first caught the sound of C-47 engines approaching. Jibilian rushed onto the field to give the identification signals with an Aldis lantern (a lantern built to send focused pulses of light). He squeezed the trigger three times with the predetermined signal: Red, Red, Red. The lead C-47 responded with the same signal: Red, Red, Red. Jibilian gave the go-ahead signal for landing, Nan, to which the plane replied, X-ray.

“We’re on boys! This is it!” Musulin shouted to his men, who again erupted into cheers. On Musulin’s orders, the edges of the field flared to life with hay bales and green flares, the signal for the landings to commence.

Now came the trickiest, most terrifying part of all for the pilots of the Fifteenth Air Force’s 60th Troop Carrier Group—landing in near darkness. The first plane overshot the runway, forcing it to take off again to avoid crashing. The other three planes coming behind it touched down successfully, followed again by the first plane on its second try. The only mishap was a crash with a haystack, which dented the wingtip of one of the planes.

Four passengers came with this first flight: Captain Jack Mitrani of the Fifteenth Air Force, two medical technicians, and OSS Lieutenant Nick Lalich, who was coming to join the Halyard team. Very quickly, they traded places with the first group of eagerly waiting evacuees, who, within 20 minutes, had said their emotional farewells with their Serb rescuers and climbed aboard the planes, ready to go. Seconds before takeoff, the side doors of all four planes suddenly opened up to reveal the departing airmen unlacing their boots and holding them up for the villagers to see.

One after another, they cast their boots out the open doors, a final expression of profound gratitude to their caretakers, many of whom had nothing more than the traditional Serb felt slippers for shoes.

Takeoffs, like the landings, were successful, but just barely. Nervous about the dangers and difficulties of night landings, Musulin ordered Jibilian to request a daytime pickup from Bari.

Two more flights of six C-47s each came the next morning, one plane landing every five minutes, this time with a strong escort of North American P-51 Mustang and Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters. While the fighters peeled off to shoot up nearby German garrisons and the German airfield at Kraljevo as a diversion, the C-47s were able to land much more safely than the night before. As each plane landed, crowds of screaming Serb women surrounded it, pelting it with flowers, to which both the outgoing airmen and the transport aircrews responded enthusiastically with boisterous noisemaking of their own. In the ensuing chaos, Musulin had his hands full herding the airmen onto the planes and keeping the crews on task.

The operation went off mostly without a hitch, except when a P-51 coming in with the second wave of transports got its left wheel stuck in the mud at the edge of the landing strip after the pilot disobeyed instructions from Lalich, who was acting as the ground-control officer. Musulin instantly recruited 100 Serbs to dig the plane out and send it on its way.

At the end of that first 24 hours of operations, the Air Force had ferried 289 Allied airmen—including 38 Frenchmen, Italians, Yugoslavs and Russians—out of Serbia to safety. Once the last plane had departed, the Halyard team and the Chetniks retreated higher into the mountains, fearing that the landings had caught the Germans’ attention. They remained in hiding for several days, but when the Germans made no moves, the OSS team went back into operation, collecting downed airmen and receiving regular air-supply drops.

By the end of August, the Halyard team had gathered enough airmen for another airlift. The Air Force sent transports on the nights of August 26 and 27, which picked up another 60 airmen to take back to Italy.

Halyard’s initial success was soon marred by trouble for George Musulin, who had to return to Bari on August 27, leaving Nick Lalich in place as mission commander. After the war, Musulin claimed that the OSS had ordered him to return in order to aid the Air Force in preparing “new escape maps for proper briefing” for Americans that went down in Chetnik territory. The actual truth was that Musulin had disobeyed the ban on Chetnik aid by approving the medical evacuation of two seriously wounded Chetniks on August 10. Two Partisan soldiers waiting on the other end in Bari recognized them as Chetniks, and before the end of the day Musulin’s superiors had ordered him home for aiding the forces of the officially disgraced Mihailovich. Musulin resisted his own recall for two weeks before giving in.

Meanwhile, as a reward for their assistance in the initial airlifts, the Chetniks received 1½ tons of medical supplies from the Americans at Bari, despite the opposition to such aid in Anglo-American circles.

While the evacuation operation was getting rolling, outside events in the rest of Yugoslavia conspired to interrupt things. Partisan leader Marshal Tito, now firmly in control of all the Yugoslav provinces but Serbia and parts of Bosnia, launched a final drive in September 1944, to thrust into Serbia, crush Mihailovich’s forces, and solidify his grasp on power.

Partisan forces, having bypassed the German garrisons around Pranjani, closed in on Chetnik headquarters and fought with Chetnik units outside the town for several days. Mihailovich’s Chetniks, who had already suffered tremendous losses of territory, men (through desertion), and arms because of the cutoff of Allied aid, were forced to evacuate the town on September 10, the Partisans hot on their heels. The Halyard team had no choice but to leave with the Chetniks, and from this point forward the evacuation operation was a traveling road show throughout Serbia and Bosnia.

The Halyard team and their Chetnik partners first moved 30 miles northward over the Suvobor Mountains to Mijonice, and from there on to Koceljeva, where they found a new airstrip.

Evacuations over the next three and a half months were carried out on an improvised basis, using whatever broad, flat spaces were available and close by, such as farmers’ fields. Even as the Chetniks moved into Bosnia, they continued collecting airmen—Americans, British, French, Italians, and Russians—for evacuation. While a battle between Chetnik and Partisan units raged just four miles away, two C-47s landed on September 17 to airlift 24 airmen out, as well as some of the Halyard medical team and navy photographer J.B. Allin.

From Koceljeva, the party crossed into Bosnia over the Drina River and continued into the Trebava Mountains, picking up more American airmen as they went. Moving on from there, the team readied a new airstrip at Boljanic and then again moved south past Sarajevo to the end point of their odyssey at Okruglice.

By November, three months after the end of the Ploesti campaign, the stream of downed aviators had slowed to a bare trickle. Only two more groups of airmen were known to still be in the country: 16 in Visegrad, who later made it to Okruglice, and nine more who were waiting in Boljanic. Clearly, the Halyard team’s job was done, and the time had come to depart. The OSS leadership in Bari offered Lalich two options for the final evacuation: have the nine airmen at Boljanic come down to Okruglice, after which they and the mission could get picked up on the Adriatic coast, or turn themselves and the remaining 25 evacuees over to the Partisans for evacuation from the interior. Lalich strongly insisted on being picked up at the Boljanic airstrip.

In one of his last meetings with Mihailovich, Lalich relayed to the Chetnik leader an offer from the OSS to evacuate him on the last flight out of Boljanic. The case for giving up the fight was strong by this point in the war, as Mihailovich’s situation had grown extremely dire. Partisan attacks destroyed his main fighting force in October, while the incoming Soviets, who had briefly joined the Chetniks, Partisans, and Bulgarians in fighting the retreating Germans, turned about to join the Partisans in fighting the Chetniks.

Mihailovich continued hoping for a landing in Yugoslavia by the Western, non-communist Allies. As those hopes began to wane, the desperate Chetnik leader secretly began joining forces with anyone who would help him take his stand against the Partisans—even the pro-fascist forces of the German puppet ruler of Serbia, former Yugoslav Army General Milan Nedich, and the Germans themselves.

At any rate, Mihailovich had no interest in leaving Yugoslavia, preferring to share the fate of his own people. “I was born here on this soil,” he told Lalich. “I will stay with my people on this soil, and I will be buried in this soil.”

As snow fell on the morning of December 11, Mihailovich assembled 2,000 Chetniks in Okruglice for a farewell salute to the last 16 airmen and a final exchange of gifts, a kama (two-edged Serbian knife) for Lalich and Vujnovich, and additionally, Mihailovich’s Serbian insignia patch, which he had worn for four years and now gave to Lalich as an uspomena (souvenir). Ironically, it read, “Samo Sloga Srbina Spasava,” or “Only Unity Saves the Serbs.” In return, Lalich gave Mihailovich his American carbine. As the time came to say goodbye, Lalich was so overcome with emotion that all he managed to say was, “Thank you for everything.”

The Halyard mission and their charges left with a guard of 40 Chetniks to guide them the last 150 miles through the mountains northward to Boljanic, stopping only for a church service at a Serbian Orthodox monastery.

The last evacuation flight left on December 27, 1944, from Boljanic in the Ozren area of Bosnia, but not before delivering 600 pairs of boots for the raggedly dressed Serbs, a last-minute act of generosity by George Vujnovich, who had cleverly requisitioned them from the British in defiance of the ban on aid to Mihailovich.

Halyard’s job was now finished. They had airlifted out a grand total of 512 downed Allied airmen without the loss of a single airman or plane, truly an impressive accomplishment. The closing act of Operation Halyard was yet to come, though.

By late 1944, the end of the war in Yugo-slavia was near. The fighting pushed most of the Germans out of Yugoslavia in the early months of 1945, although some continued clinging to their shrinking toehold in the country as late as April. The grinding war of attrition battered Mihailovich’s Chetnik army to pieces until only a small handful of men were left. Mihailovich and his remaining followers held out in the mountains until the Yugoslav Department of National Security (the new Tito government’s internal security agency) captured the Chetnik leader on March 13, 1946.

In March 1946, news of Mihailovich’s capture and impending trial for war crimes by the new Tito government of Yugoslavia reached former Halyard participants in the United States. Outraged and strongly convinced of Mihailovich’s innocence and loyalty, they immediately mounted a public campaign to clear Mihailovich’s name. A meeting with Secretary of State Dean Acheson secured State Department aid in forwarding evidence of Mihailovich’s innocence from the former evacuees to the Yugoslav government. It was rebuffed. Mihailovich was tried and convicted, then shot on June 17, 1946, and buried in an unmarked grave.

In a generous but futile gesture, U.S. President Harry Truman posthumously awarded Mihailovich the Legion of Merit on March 29, 1948, on the recommendation of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, but the award remained classified for 20 years because of concerns the State Department had of offending the Yugoslav government now led by Mihailovich’s opponent, Marshal Tito. A U.S. State Department delegation, including Vujnovich, Jibilian, and a number of the surviving evacuees finally presented it to Mihailovich’s daughter, Gordana, in the United States on May 29, 2005.

Kevin Morrow is a writer, editor, and former archivist at the U.S. National Archives who currently lives in McLean, Virginia. He released his first book on German covert operations in the Middle East during World War I in 2018.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments