By William E. Welsh

Bright sunshine flooded the sedge-covered, damp ground in Sussex on the morning of October 14, 1066. Having attended mass at sunrise, Duke William of Normandy shouted commands to his senior officers outlining their positions for the coming battle with English King Harold II Godwinson’s army.

A towering, swarthy figure with broad shoulders, William commanded respect. He wore a long hauberk and helmet. A necklace of religious relics hung around his neck. The duke’s courage and confidence inspired those who fought for him. He had led them to repeated victories on the continent, and they had believed he could vanquish the English as well. William’s knights fully expected that their duke would reward them for victory by granting to them English fiefs, and the foot soldiers envisioned plunder that would enrich them far beyond their normal means.

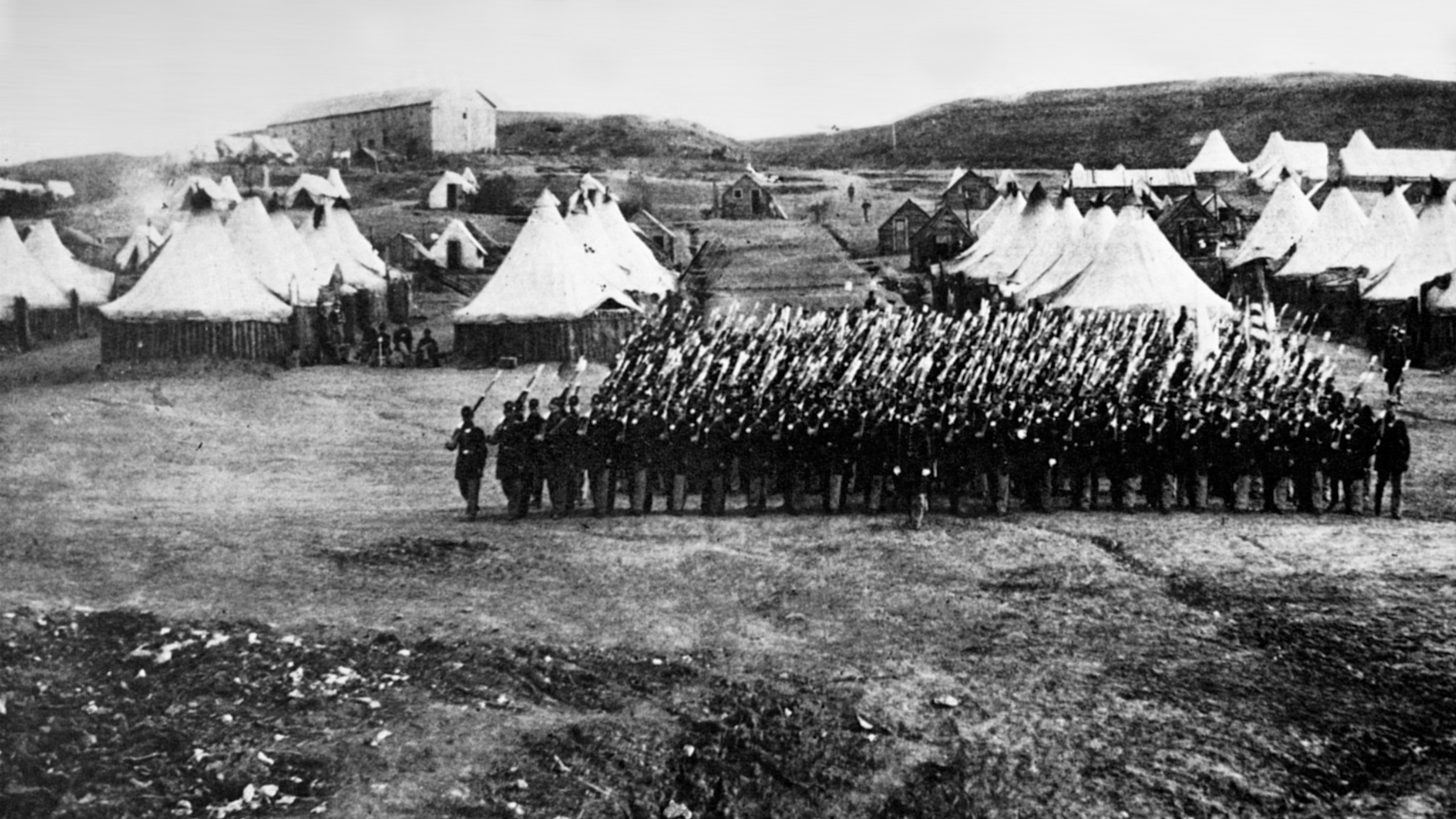

On the morning of the battle, the Norman army was situated seven miles north of its fortified base on Hastings Peninsula. Just offshore vessels of varying size in the Norman fleet rocked at anchor, their captains ready to respond promptly to the duke’s orders should he need them to ferry his troops to another point on the coast. The armies were matched in strength, with each numbering about 5,000 men. Harold had 2,000 housecarls and 3,000 militia, all of which fought dismounted, while William had 2,000 cavalry and 3,000 foot.

Both commanders believed a pitched battle was a necessity. They had marched to meet each other in battle to resolve by force of arms the matter of who would henceforth rule England. Godwinson’s army had countermarched to Hastings from its victory in northern England on September 25 against an invading Viking army. He had hoped to surprise William as he had done the Vikings at Stamford Bridge, but when he reached Senlac Hill in the late afternoon of October 13, he found the Normans prepared for battle. Harold had hoped that William would be thunderstruck by the sudden appearance of his army, but it was the English king who had the unpleasant surprise. Both commanders waited for dawn to begin the battle.

King Harold’s foot soldiers and dismounted cavalry formed up on October 14 in a tightly packed shield wall. The shield wall was designed to absorb heavy enemy assaults and gradually wear down the attacking army. Owing to the relatively compact front atop the ridge, the English troops stood 10 ranks deep. The core of the English host, consisting of 2,000 housecarls, occupied the center of the line. The housecarls, clad either in mail hauberks or sturdy jackets of leather hide, stood side-by-side. Their kite-shaped shields could be held high to deflect missile blows, but also could be planted in the ground to free up their arms to wield their long shafted, two-handed battle-axes.

The wings of Godwinson’s army consisted of the well-trained militia that constituted the English fyrd. The freemen of the fyrd also presented their shields, but they would fight that day with spears and swords. Both the professional soldiers and the militiamen had drilled extensively to perfect their shield wall tactics.

Duke William’s army formed up in three ranks along ethnic lines. The Bretons deployed on the left, the Normans in the center, and Franco-Flemish on the right. William placed his crossbowmen and self-bowmen in the first rank, mail-clad heavy infantry in the middle rank, and hauberk-wearing knights armed with lances in the rear rank. The Norman army had large numbers of archers, whereas the English host had very few. Whereas the English fought with axes and spears, the Norman foot in the second ranks fought with javelins and swords.

Duke William entrusted his cavalry with a principal role, and his foot soldiers with a secondary role. He told his high-ranking knights that they were to lead their mounted troops in repeated uphill charges in a quest to pierce the English shield wall. If repulsed, they were to regroup and charge again. He emphasized that they were not to quit until they broke the English line. William believed that if his horsemen could pierce the shield wall in one or more places, the English formation would dissolve. As for the Norman archers and spearmen, William tasked them with weakening the enemy to the point where the cavalry could get among them.

The stage was set at mid-morning for an earth-shattering battle that had the potential to alter the course of history should the Normans prevail. In many ways, Harold had the advantage given that he would be fighting a defensive battle in his homeland. The odds seemed heavily stacked against Duke William, although to his credit he already had succeeded in crossing the English Channel with a vast armada and gaining a toehold in southern England. But that alone was not enough. To win the crown, the Norman host would have to vanquish the English army on Senlac Hill. Should the English lose the battle, but retreat in good order, William would have to fight them again. The duke knew all too well that keeping his troops supplied in a foreign land posed a major challenge.

The succession crisis in 1066 followed the death on January 5 of that year of the weak English King Edward the Confessor. Having died without an heir, a power struggle was bound to occur. The English had great difficulty controlling the English crown in the early 11th century. King of Denmark and Norway Sven Forkbeard had succeeded in 1013, conquering England when he drove King Ethelred “The Unready” into exile in Normandy. In a bid to strengthen his alliance with Normandy, Ethelred wed Emma, the daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy, in 1002.

Although Forkbeard died the following year, he was succeeded by Canute. Ethelred returned to England and took the crown for a second time, but Canute, who was Forkbeard’s son, soundly defeated the English at Ashingdon in Essex in 1016 to win the crown of England. With Canute’s line having ended in 1035, Edward the Confessor, the son of Ethelred and Emma, ascended to the throne of England. He wed Edith, the daughter of Earl Godwin of Wessex. Edward’s second son, Harold, who became Earl of Wessex in 1053, rose to prominence as the king’s principal counselor. When Edward died on January 5, 1066, Harold Godwinson ascended to the throne.

Godwinson, whose father was Earl Godwin of Wessex and mother was Canute’s sister Gytha, became Earl of Wessex in 1053. As Earl of Wessex, he gained the respect and admiration of the English population of England for his successful campaigns against King Gruffydd ap Llywelyn of Wales in a war that stretched from 1052 to 1063.

Godwinson dealt the final blow to Gruffydd in 1063 when he masterminded a two-pronged invasion in which he led a fleet against coastal targets in South Wales while his brother Earl Tostig of Northumbria invaded North Wales. Harold proved flexible over the course of the campaign by adopting some of the Welsh tactics. The campaign ended with the Welsh rejecting Gruffydd and submitting to Godwinson.

The Earl of Wessex campaigned with Duke William in 1064 during the Norman-Breton War against Duke Conan II of Brittany. Sources are conflicted as to the reason he was in France. He may either have been accidentally shipwrecked on the coast of France or may have journeyed to the continent to retrieve relatives that were still living in exile in northern France.

This gave each commander an opportunity to assess each other. William came away from the experience with considerable respect for Harold’s capabilities. But Harold drew the wrong conclusions about William. Godwinson grossly underestimated William’s capabilities, misinterpreting his caution and willingness to negotiate for a lack of courage.

Godwinson’s successful campaign against the Welsh convinced the English people that he was the noble best suited for the English throne upon Edward the Confessor’s death. Although he lacked royal blood, the Earl of Wessex was wealthy, popular, and well-regarded. By the time of Edward’s death, Godwinson was seen as a mature commander with extensive military experience who had the necessary traits to successfully rule the kingdom and defend it against both internal and external threats.

Godwinson became the first English king to be crowned in Westminister Abbey in a ceremony held on January 6, 1066. The most immediate threat to King Harold’s reign came from his brother Tostig, who had been a long history of running afoul of the English crown. Tostig reigned as Earl of Northumbria for a decade beginning in 1055. During his tenure, he studiously avoided the court of King Edward, and cultivated alliances with the Scots and Danes. In November 1065, Edward banished him from England with Harold’s support.

Tostig wintered in Flanders. Count Baldwin of Flanders, who was an enemy of the English, gave Tostig 60 vessels with which to raid the English coast. Tostig sailed to the Isle of Wight in May 1065, where he recruited troops and then began raiding east along the coastline of Sussex and Kent. Unable to land in Northumbria because he was outnumbered by the local forces who remained loyal to King Harold, Tostig sailed north to Scotland, where he was granted safe haven. Tostig lacked the power to retake Northumbria, his old earldom, without greater support than Count Baldwin could provide. Tostig therefore requested military aid from Harald Hardrada, the King of Norway.

It was not worth Hardrada’s time, though, to merely reinstall Tostig in Northumbria. Hardrada planned to conquer England. The Norwegian king had a loose claim to the throne both through his nephew, King Magnus of Norway, who had died in 1047, and Canute’s son Harthacnut, who had ruled England briefly following his father’s death. The two kings, Magnus and Harthacnut, had entered into a pact whereby each had agreed to succeed the other if they died without heirs.

William was a seasoned commander by the time he invaded England. Born in Falaise in 1028, he was the illegitimate son of Duke Robert I of Normandy. Duke Robert made William his heir before embarking on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1035. Robert died in Nicea on the return leg of his journey.

Duke Robert’s death touched off the so-called Norman Baronial Revolt, which dragged on for 12 years from 1035 to 1047. Rebellious lords nearly assassinated the young bastard on several occasions in the years immediately following his father’s death.

William actively campaigned in Normandy throughout the 1040s in an effort to solidify his rule of the duchy. As duke of Normandy, he was a vassal of French King Henry I. During those years, William showed great promise as both a courageous warrior and an astute commander. By 1047 William had crushed internal resistance to his rule. Over the course of the next seven years he fought off external threats from his sovereign, King Henry, as well as Count Geoffrey II of Anjou, both of whom had designs on Norman lands.

William learned through these campaigns that the patient commander was often the victorious one. He generally avoided a pitched battle, biding his time with the hope of attacking a part of his enemy’s army under favorable circumstances. He had compiled a string of victories that included Val-les-Dunes in 1047, Mortemer in 1054, and Varaville in 1057. The victories would give him the confidence in the following decade to dream of conquering England.

Both King Henry and Count Geoffrey died in 1060. Their deaths enabled William to go on the offensive to conquer territory in neighboring provinces. William had already expanded to the west by making the count of Ponthieu his vassal. William then annexed the County of Maine. The following year he invaded Brittany, which touched off a short Breton-Norman War. William was supported in his war against Duke Conan II not only by a powerful Breton lord, Rivallon I of Dol, but also by Count Geoffrey III of Anjou. Through these campaigns of conquest, William had shown that he had successfully mastered key aspects of military command, such as reconnaissance, rapid marches, siege warfare, and how to supply an army in the field.

Not long after Harold was crowned King of England, William sent envoys to the English court to set forth the grounds for his claim to the throne and to urge King Harold to renounce his kingship. William knew full well that King Harold would not step down. The diplomatic mission was a clever ploy on William’s part because it allowed him to position himself as the injured party in the matter. He could then say he was left with no choice but to seize the throne by force.

In the interim, William loudly voiced his objection to Harold Godwinson’s ascension to the throne. The Norman duke claimed that Edward the Confessor had named him earlier as his successor while living in exile in Normandy during the reign of Canute. Moreover, William asserted that Godwinson had earlier agreed to support William’s claim during his time in Normandy in 1064.

William had to recruit a large army for the expedition. Since there were not enough troops in Normandy to defeat the English, he had to recruit additional troops outside the duchy. He cleverly obtained the support of Pope Alexander II for his claim. He did this in part by telling the Pope that he would maintain stronger ties to the Church of Rome than had King Harold. Pope Alexander believed William, and he went so far as to send him a Papal banner to carry into battle against the English.

Having the Papal blessing was a boon to William’s cause because it marshaled the support of the nobility of northern France to his side. In the wake of the Papal endorsement, nobles, knights, and mercenaries in northern France rallied to support him. William’s vassals form Normandy, Maine, and Ponthieu either joined the expedition with their retainers or furnished troops for it. Bretons and Flemish also signed on. William even received support for his claim to the English crown from the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and the Danish King Sweyn II Estridsson.

In the first week of September, King Harald of Norway set sail for England. He recruited additional Viking troops along the way. He stopped in the Shetland Islands and Orkney Islands, as well as mainland Scotland. He arrived at Tynemouth on September 8 with 300 ships containing 10,000 men. Before the month was out, Hardrada and Tostig had sailed up the Humber and defeated the Yorkshire militia led by Earl Edwin of Mercia and Earl Morcar of Northumbria in a hard-fought battle on September 20 at Gate Fulford outside York.

King Harold Godwinson had summoned the English fyrd in late spring following Tostig’s raids. But the fyrd was summoned more to deal with the pending Norman invasion than to deal with future raids by Tostig. Harold likely called up the Wessex fyrd to serve in southern England, where he correctly expected Duke William to land his invasion force. Harold did not summon the fyrd from Northumbria or Mercia, for he wanted to allow the loyal earls in those regions to have troops with which to contest an invasion by Tostig and his allies. Most importantly, William also summoned the shipfyrd, which was England’s fleet. The fleet was tasked with patrolling the English Channel to contest a crossing by the Norman fleet.

All freemen of fighting age had to perform military service for a specified number of days each year for the English king. Fifteen thousand men throughout all of England served in the fyrd in 1066. Earls could call up the fyrd in their region, and the king could summon all of the freemen in times of dire national crisis. As for the housecarls, who served as the household troops of kings and earls, they owned large tracts of land—much larger than the parcels owned by freemen—and were well schooled in the art of war. Unlike the freemen, the housecarls were permanent, professional soldiers who served year-round, rather than the two months’ service typically required of the fyrd.

But when the Norman invasion failed to materialize by the first week in September, Harold had little choice but to dismiss both the fyrd and shipfyrd, which he did on September 8, because they had served for a longer period than usual.

The clash at Stamford Bridge on September 25 against Harald Hardrada’s Viking army substantially weakened Godwinson’s English army. Harold initially had 3,000 housecarls under arms, but 1,000 were killed or severely wounded at Stamford Bridge, which left him just 2,000 of these elite troops to form the backbone of the fyrd that would face the Norman army at Hastings. Unfortunately for Harold, not all of the troops who survived Stamford Bridge would fight at Hastings. Some of the troops that fought at Stamford Bridge—angered that Harold had not shared his Viking plunder with them—returned home instead of accompanying him south to battle the Normans.

Throughout the summer of 1066, William went about gathering the resources for the invasion. William called on his magnates to finance the construction of ships in Norman ports, and also purchased vessels from his allies. The Norman fleet, composed of 600 shallow-draft longships and deep-drawing cargo ships, assembled in July at Dives-Sur-Mer, but bad weather delayed the fleet from sailing. In late August the fleet sailed northeast to St. Valery sur Somme in Ponthieu in preparation for crossing the storm-tossed waters of the English Channel. William ordered the 2,000 horses taken by land to St. Valery sur Somme where they would be loaded at the last minute when the fleet was ready to sail for England.

William faced a daunting task, for he had to assemble a fleet from scratch, undertake a perilous crossing, and establish a foothold in hostile country. In addition, King Harold “both in wealth and number of soldiers in his kingdom was greatly superior to [the Normans],” wrote William of Poitiers.

William’s armada hove to at Pevensey on September 29. Although the duke had intended to use the Isle of Wight as a staging area, strong westerly winds blew his ships off course, and the heavily laden vessels were forced to land further east than William and his naval officers had intended. The duke sent his archers ashore first to reconnoiter the ground. These men, who were unarmored, were quick-footed. They carried a self-bow that they drew to their jaw or chest to fire. They were “ready to attack, ready to flee, ready to turn about, and ready to skirmish,” wrote Master Wace, a Norman chronicler. “They scoured the whole shore, but not an armed man could they find there.”

Once William determined that there were no English troops to dispute the landing, he ordered his heavy infantry and horsemen ashore. William put a large number of his troops to work immediately building an earth-and-timber castle with which to defend the landing site. He also sent forage parties to scour the surrounding countryside for crops and livestock.

When Henry learned on October 1 that the Normans had landed, he marched south with his housecarls to block their advance towards London. Since most of the militiamen from Mercia and Northumberland had returned home after Stamford Bridge, William sent mounted messengers to the southern shires summoning the freemen in that area to come to his aid against the Normans.

Rather than offer battle immediately to the Normans, Harold might have taken another course of action. He might have undertaken a scorched-earth approach in the shires south of London to deny the Normans forage. But Harold hoped he could surprise and rout the Normans in the same way he had the Vikings at Stamford Bridge. Based on his time in France in 1064, he had formed a negative opinion of William’s method of waging war. For this reason, he resisted attempts by his kinfolk to convince him to stay in London and possibly let someone else lead the English troops into battle. When he arrived in London on October 6, his younger brother, Gyrth, pleaded with Harold to send him to lead the army in battle so Harold would not be risking his life. But the king would not hear of such a thing.

Harold waited five days for militia reinforcements to augment the professional core of his army in London. He departed London, with his brothers Gyrth and Leofwine, on October 11 at the head of his army. He led his army south through the forested Weald, an area that divided the chalk escarpments of the north with the South Downs, and on to Hastings.

Harold had hoped to attack the Normans immediately, but Norman scouts ranging north had learned on October 12 that the arrival of the English was imminent. When they informed William of the pending arrival of the English, he had his troops sleep on their arms that night. Harold had an unpleasant surprise when he arrived on Senlac Hill at dusk on October 13 to find the Normans expecting him. William’s readiness spoiled Harold’s plan for a surprise attack.

The battlefield was situated six miles north of Hastings along the London road. The flanks of both armies were anchored on marshland. The valley below Senlac Hill where the Normans would form up the following morning was damp and covered with sedge. The valley was “untilled because of its roughness,” according to a contemporary source. The terrain also posed limitations for the English because the forest and wet ground behind Senlac Hill would make a withdrawal difficult should the English attempt to break off the fight.

Harold deployed his troops on Senlac Hill with his army facing south astride the London Road. His housecarls were stationed in the center with the men of the fyrd deployed on the wings. Harold believed that having his troops on a hill with steep slopes would nullify the strength of the Norman cavalry, for he hoped the knights would lose momentum charging uphill. Yet the only real way to nullify the attack of the mounted Norman knights would have been to construct ditches in front of the English position to block cavalry charges. But events moved quickly, and there was no time for that.

William deployed the Bretons on the left, Normans in the center, and Franco-Flemish on the right. The mounted Norman knights had the advantage of using the recently adopted stirrup, which aided them in staying astride their horses following the shock of the lance against the enemy. The English had only a few archers and no cavalry.

William had his Normans ready to advance at 9:00 am. The Norman front rank moved to within 200 yards of the English, which put the crossbowmen and self-bowmen within range of the Anglo-Saxon shield wall.

“The harsh bray of trumpets gave the signal for battle on both sides,” wrote chronicler William of Poitiers. “The Norman [archers] closed to attack the English, killing and maiming many with their missiles. The English resisted bravely, each one by any means he could devise. They threw javelins and missiles of various kinds, murderous axes and stones tied to sticks.”

Unfortunately for the Norman bowmen, the English troops’ elevated position lessened the arc of their crossbow bolts and arrows. For this reason, their initial missile fire was largely ineffective. Many of their missiles struck the wooden shields of those in the front rank.

Next, William ordered his mail-clad heavy infantry to advance. Although they assailed the shield wall, they failed to make a dent in it. The English spearmen successfully jabbed at the Norman foot soldiers, and the housecarls wielded their two-handed axes with deadly efficiency. The Norman heavy infantry had no choice but to fall back.

William then ordered his cavalry in the third rank to charge the English position. Like the archers and foot soldiers that had preceded them, the cavalry also failed to breach the shield wall. The carnage among the Normans in three assaults was enough to shatter the morale of the Bretons. They began to flee from the battlefield, but William’s half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, rode after the Breton commanders. He scolded them loudly for abandoning the field prematurely. His harsh words compelled many of the Bretons to return to the field.

Harold might have won the day if he had launched an all-out counterattack on the Normans and Flemish before the Bretons returned, but he intended at that point to fight a purely defensive battle. He likely believed that if he could hold his ground, William would face an embarrassing loss that might compel him to quit England.

Unexpectedly for Harold, a large group of spear-wielding militia on his right flank sallied forth. They charged downhill in hot pursuit of the Bretons. William directed his cavalry to cut down the militia, which they did in short order. It was an unexpected break for William in a battle that had not been going his way at the outset.

Some of the English spearmen who streamed downhill after the first series of Norman assaults also attacked the Normans in the center. During this melee, William had the first of several horses killed from underneath him. A rumor spread like wildfire through the ranks that William was slain. Sensing the concern of his troops, he quickly commandeered a new mount. He then removed his helmet and rode back and forth to show his troops he was still very much in command of the army. “Look at me, I am alive and with God’s help I will conquer,” shouted William. At that point, the Norman knights encircled and finished off the last of the Englishmen who had charged downhill in violation of Harold’s orders that they were to remain on the defensive.

Although it was disheartening for the English on the hilltop to watch as the militia in the valley was gored by spears or hacked down by swords, they maintained their static position. As the battle progressed, it became evident that King Harold, who was stationed in the center of his army surrounded by his bodyguards, was having difficulty controlling the militiamen on the flanks. His housecarls, though, maintained good order and discipline.

The battle became one of attrition as each side sought to hold out until the other weakened enough to crumble under a heavy blow. A lull occurred in the battle while the Duke of Normandy considered his next steps. William surmised that if he could compel more of the English troops to come down off the hill, he would weaken the English shield wall to the point that it would crack. He therefore ordered the Franco-Flemish troops on his right wing to charge the shield wall and pretend to flee down the slope of Senlac Hill in panic after their charge. William had confidence that the Flemish knights could conduct feigned retreats because they were elite, professional warriors who possessed superb discipline. He hoped this feigned retreat would succeed in drawing off a like number of spearmen from the English left flank.

The Franco-Flemish feigned retreat worked exceedingly well. Large number of English spearmen took the bait. The French and Flemish knights fled just far enough to draw the spearmen onto the valley floor before wheeling about and counterattacking the hapless Anglo-Saxons that had fallen for the ruse. Caught on open ground in a loose formation, the English spearmen could mount no effective defense against the Normans.

“A combat of an unusual kind began, with one side attacking in different ways and the other side standing firmly as if fixed to the ground,” wrote William of Poitiers. As the day wore on, the English grew noticeably weaker, particularly on the wings. The English housecarls on the hilltop tightened their formation; and as they did so, they made an easy target for the Norman archers.

Moving ever closer to the enemy formation, the crossbowmen fired their bolts at close range. This time, they aimed for the helmets of the English in a quest to inflict deadly facial or head wounds. William “instructed the archers not to shoot their arrows directly at the enemy, but rather into the air, so that the arrows might blind the enemy,” wrote Henry of Huntingdon, an English churchman and chronicler.

The crossbow and arrow fire at this stage kept the housecarls pinned down. As the missile fire further winnowed King Harold’s ranks, already depleted by the unauthorized piecemeal attacks of the English spearmen, the Norman knights began a series of fresh charges in which they succeeded in piercing the English line. Whether Harold’s brothers, Gyrth and Leofwine, already were dead because they had participated in the downhill assaults or whether they were slain in the final phase of the battle is unclear.

Having pierced the shield wall, a group of 20 picked knights on their warhorses began fighting their way toward Harold. His position was clear for all to see, for he not only fought under the dragon standard of Wessex, but also under his bejeweled personal banner of the Fighting Man. But it would not be the knights that slew the English king at dusk that day.

As the knights were attempting to seize his standard and kill or capture him, a shower of arrows “fell around King Harold, and he himself fell to the ground, struck in the eye,” wrote Huntingdon. At that point, most of the remaining troops fled, save for a small number of the king’s bodyguards who fought to the death. The victorious Norman troops swept up the standards of Harold and his earls to present to Duke William.

The Norman pursuit lasted one hour before darkness put an end to it. Some French sources describe how the English fought a rearguard action at an old Anglo-Saxon earthwork on the London Road protected by a series of ditches beyond Senlac Hill. Some of the Norman horsemen involved in the pursuit were either killed or wounded when their horses tumbled into the deep ditch in front of an earthen rampart in the dark. The French sources refer to the wide trench in their account as Malfosse, which means evil ditch.

William’s victory at Hastings did not mean he had conquered England. When no word came of the submission of the nobility and senior clerics to William’s authority, he began a circuitous march on London that lasted 10 weeks. He first marched to Kent, where he received reinforcements from Normandy in Dover and other ports. He then counter-marched west to Hampshire and then north to Oxfordshire. William arrived north of London in Herefordshire in early December, having marched 350 miles. During his long march his army had fought a series of minor actions with pockets of resistance.

The remaining earls and senior clerics submitted to William on December 10 acknowledging him as their king. William was crowned the new king of England in Westminster on Christmas Day. It was not without incident, though, for the Norman knights inside the church believed mistakenly that there was a riot outside and began torching nearby houses. William, it was said, was visibly shaken by the disturbance. The war in England was far from over. It would take William the Conqueror four long years to subdue the Midlands and Northumbria.