By David A. Norris

Great Britain’s war with her rebellious American colonies was about to conclude as diplomats crafted a peace treaty. At the same time, across the Atlantic Ocean from the almost-independent United States, the British outpost of Gibraltar faced its greatest threat since the Union Jack had first floated over the little peninsula. Backed by 47 Spanish and French ships of the line, 200 siege guns of the Spanish Army opened fire.

On the water, an ominous line of 10 formidable floating batteries loomed ever closer to Gibraltar’s defenders. Shielded with three feet of massive oak timbers, the specially built Spanish vessels carried a daunting broadside of heavy guns. Reaching their firing positions, the floating batteries dropped their anchors and threw a nonstop barrage of shot and shell into the British works. Guns blazed in reply from Gibraltar, but even red-hot shot seemed to bounce off of the oak timbers to splash sizzling harmlessly into the sea. The grand assault of September 13, 1782, threatened to end the British possession of the Rock of Gibraltar.

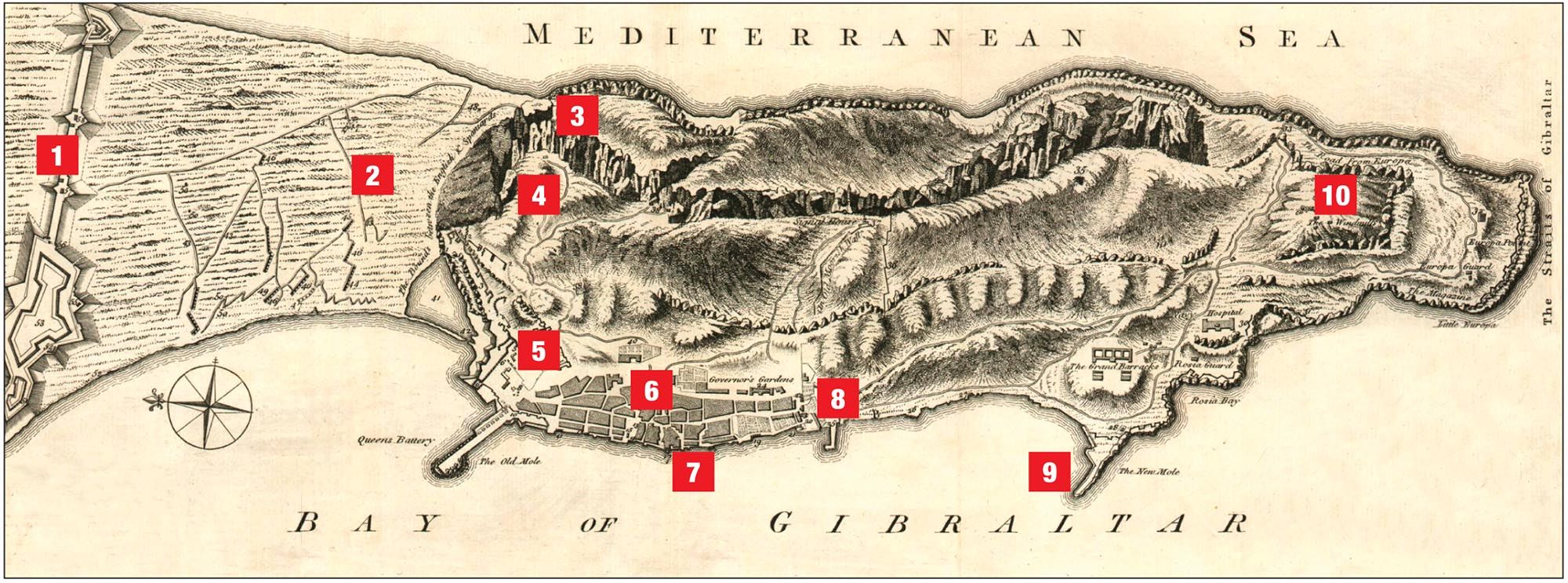

A little peninsula, three miles long and threefourths of a mile wide, Gibraltar was attached at its northern end to the Spanish mainland. Looming over the peninsula was the “Rock,” a massive stone mountain that overlooked the Straits of Gibraltar. Known to the Romans as Mons Calpe it was, along with Mons Abyla on the shore of North Africa, one of the twin “Pillars of Hercules” flanking the eight-mile gap between the continents of Europe and Africa, where the Mediterranean Sea met the Atlantic Ocean.

The peninsula of Gibraltar forms the eastern edge of the Bay of Gibraltar, which is five miles wide and six miles long from north to south. The lower end is open to the strait. On the western edge of the bay, opposite Gibraltar, is the Spanish port of Algeciras.

When the War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701, Gibraltar was part of Spain. After centuries of contention with the Moors, possession of the peninsula was a point of pride for Spain. Spanish silver coins showed an allegorical version of the Pillars of Hercules in the form of two classical columns. British forces seized Gibraltar in 1704, and London gained formal control of the strategic peninsula through the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 that ended the long war.

Spanish inhabitants of Gibraltar left the peninsula after the treaty. British merchants, artisans, clerks, apprentices, and servants arrived to replace them. Jewish refugees from around the Mediterranean, many of whom were born in North Africa, found homes there. Other residents hailed from Genoa, Savoy, or Minorca. Genoese and Portuguese fishermen helped feed the British garrison with their catches. A census count of the civilian population in 1777 found 506 Protestants of British blood, 1,832 Catholics (only 13 of British extraction), and 863 Jews.

The nation that possessed Gibraltar had a powerful military and naval base to exert control over sea traffic entering or leaving the Mediterranean Sea. The enormous numbers of European and Ottoman ships passing through the Strait of Gibraltar were a substantial portion of the world’s maritime trade.

Passage through the strait might be delayed for days or weeks by contrary winds, so a friendly port nearby was an invaluable asset for Great Britain.

A Spanish siege in 1727 did not force the British out. Gibraltar was only seriously threatened afterward when the American Revolution widened from a colonial rebellion to an international war involving Europe’s major powers. France allied with the American rebels in 1778, and was soon joined by the United Provinces of the Netherlands and Spain.

The Spanish did not plan to send troops to join American General George Washington. Instead, with the help of the French army and navy, Spain hoped to regain possessions lost to the British in previous wars. The alliance against London looked like Spain’s best chance yet of getting Gibraltar back.

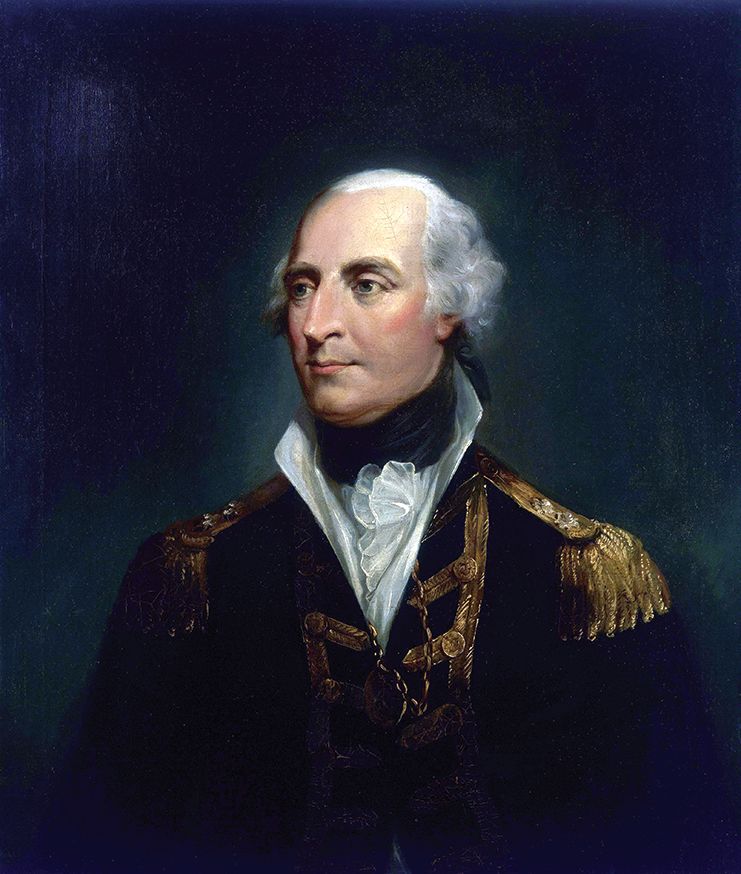

It fell to sexagenarian British Lieutenant General George Augustus Eliott, who had taken over as governor in 1777, to defend Gibraltar. A veteran of four decades of service, he had reaped enough prize money from the capture of Havana in 1762 to buy a large estate. Quite unusually among his peers, Eliott was a vegetarian and teetotaler; just the same, he allowed his men their customary rations of alcohol.

Gibraltar’s Rock, a limestone ridge two miles long and up to 1,398 feet high, is the main feature of the peninsula. The Rock’s steep eastern side, facing the Mediterranean, plunges downward into the water with little interruption, and offers no landing places to forces of any size. Beyond the northern slope of the Rock, access to the British works was partially blocked by a marshy stretch called the Inundation, near the northwest corner of the Rock. Two narrow passages around the Inundation were blocked near the Bay of Gibraltar by the Bayside Barrier and to the east by Forbes’ Barrier. Beyond the barriers was 300 yards of sand, used in peacetime as garden space by the British, but now menaced by enemy guns.

Passages from the two barriers led to the Land Port, behind which loomed the guns of the Grand Battery. South and east of Forbes’ Barrier rose the sharp slopes of the north face of the Rock. Already steep and forbidding, the slopes and crown were protected by Willis’ Battery, and higher up between that point and the Grand Battery, the venerable medieval walls of the Moorish Castle.

Further east of Forbes’ Barrier, the steep slopes of the Rock curved south toward the easily defended eastern face. Gibraltar’s fortifications, port, town, and other assets were situated on its western edge, facing the bay.

West of the Grand Battery, the Old Mole jutted out into the bay. Faced with stone battlements, the mole partially sheltered the small Water Port. Spanish artillery could easily reach this area, so it would be of little use for landing cargo during the siege. South from the Old Mole, the town of Gibraltar sprawled along a narrow shelf at the foot of the Rock. In the middle of the town’s shoreline, the new King’s Bastion extended into the bay, armed with 26 guns. The south end of town was guarded by the South Bastion and the Citadel. A small wharf known as the Ragged Staff stood nearby.

After a rather empty stretch, there was another little harbor formed by the New Mole. The barracks and the naval hospital were just beyond. On the south end of the Rock was Windmill Hill, where steady breezes kept millstones turning. Europa Point and the surrounding ground, at the southern tip of the peninsula, were largely vacant.

Encouraged by its ally France, Spain went to war with Great Britain in June 1779. Elliott’s garrison then numbered 5,352 soldiers organized into five British and three Hanoverian battalions, the latter of which were commanded by Maj. Gen Auguste de la Motte. There was a contingent of marines, as well as a company of artificers—military engineers—and five companies of the Royal Artillery.

The Royal Navy’s flotilla at Gibraltar during the siege included a small and varying collection of vessels, headed by the 60-gun ship Panther and the 28-gun frigate Enterprise and some smaller vessels. Also on hand were a few privateers. Captain Robert Curtis and 900 sailors served on shore as marines.

General Martín Álvarez de Sotomayor led the Spanish army that initiated the siege in July 1779. Numbering 7,000 soldiers by September, they camped along the north shore of the bay while they constructed siege works across the neck of the peninsula.

Admiral Don Antonio Barcelo’s Spanish fleet, based at Algeciras, began a blockade. Barcelo’s fleet fluctuated in numbers, but he generally had one or two ships of the line and a few frigates with a horde of smaller warships, gunboats, and galleys. Barcelo had many Mediterranean-style vessels, such as the xebec, settee, tartane, and polacre.

Xebecs were versatile North African-style ships, used by traders and Barbary pirates before their adoption by the Spanish and French navies. These exotic-looking vessels had sharp bows and sterns jutting far out from the hull. Propelled by lateen sails, xebecs were swift and maneuverable and carried from perhaps a few cannon up to about 30 guns, about the capacity of a small frigate.

Other common regional vessels included the settee, with a single deck and lateen sails. The tartane was similar, but with only one mast. The polacre, or polacca, had three single pole masts with a combination of square and lateen rigs. Small vessels like these could carry at least one large gun within range of the British and bombard Gibraltar’s town and forts.

In preparation for the Spanish attack, Eliott sent away as many civilians as he could. A log boom blocked the Old Mole against enemy landings, and ships were sent further down to the New Mole, where they’d be a little further away from enemy siege guns. The north face of the Rock had some vulnerable approaches, so engineers cut steep scarps to eliminate gentle slopes, and built new palisades.

On September 12, 1779, Eliott opened fire on the enemy works. Sergeant Samuel Ancell, a clerk with the 58th Regiment of Foot, described how an officer’s lady, curious to see the event, was encouraged to strike the match for the first gun to be fired. Eliott then gave the order “Britons strike home,” wrote Ancell, and at that point “every battery and angle bellowed with rage, and foamed with destruction.”

Spanish land batteries along the bay joined those in the siege lines north of the peninsula. Barcelo’s gunboats slipped in close at night to bombard the British at closer range. Sotomayor intended to blockade and starve out the garrison. Hemmed into their little enclave, the British ran short of food and supplies. In peacetime, gardens on the sandy stretch north of the Rock supplied fresh produce, but as the siege got under way enemy guns commanded the garden plots. Civilians grew gardens on little scraps of land, but most of the rocky peninsula was harsh ground for trees or gardens. The hungry foraged for dandelions, thistles, and wild leeks.

Merchant ships and smugglers continually evaded the blockade and brought in a small flow of food and supplies, although never enough to satisfy the needs of the thousands of troops and civilians in Gibraltar. On January 15, 1780, it was joyous news when a British brig made it to port just ahead of the news of the imminent arrival of a relief fleet.

Admiral Sir George Rodney had sailed from England in December 1779. He escorted a vast armada of supply ships. A portion departed from him for the West Indies, while the rest sailed for Gibraltar. Rodney clashed on January 16, 1780, with a Spanish fleet under Admiral Don Juan de Langara. The fighting continued into the night, and in what became known as the moonlight battle of Cape St. Vincent, four ships of the line were captured and another sunk. The British captured de Langara.

The first ship of Rodney’s convoy reached Gibraltar that same day and the rest arrived over the course of the next 10 days. With Rodney was Rear Adm. Robert Digby. Aboard Digby’s flagship, the Prince William, was Midshipman William Henry, the third son of King George III.

Nearly a half century later, William would ascend to the throne as King William IV in 1830. While still a prisoner, de Langara visited Digby aboard the . The royal midshipman informed de Langara before his departure that his boat was ready. The Spanish admiral was impressed that in Great Britain, in his words, “the humblest stations in her navy are supported by princes of the blood.”

Less impressive was a royal visit to Gibraltar town. Prince William and some companions went to a tavern. After they drank for some time, a fight broke out between the prince’s party and some soldiers who insulted the Royal Navy. The brawlers were arrested, although the prince was quickly released when his identity became known. Rodney and Digby departed on February 13.

With them went several Spanish prize ships and several hundred Gibraltar civilians. Diverted from their intended destination of Minorca, 900 men of the 2nd Battalion of the 73rd Highland Foot stayed behind to augment the garrison.

Fishing boats still plied the bay, their crews warily filling their nets and bringing their catch back to help feed the garrison. British privateers and merchant ships continued to bring a steady trickle of supplies. Small boats slipped in from British-held Minorca, Moorish ports in Tangier and Morocco, or smuggler’s lairs in Spain.

The British garrison got by as best as it could. Ancell noted the arrival of a boat laden with chickens from Morocco. The crew had to kill the roosters, lest they crow and proclaim their presence to the Spanish Navy. Together these boats partially stocked the garrison with oranges, lemons, fowls, sheep, bullocks, wine, olive oil, leather, and shoes. Leather was scarce, and during the siege most enlisted men and many officers ended up wearing canvas shoes, with soles made of spun yarn.

Early on the morning of June 7, 1780, lookouts aboard the frigate Enterprise saw several ships approaching from the west. The sailors hailed the mystery ships, but no one answered. Flames appeared and quickly rushed up the masts and sails of the vessels, revealing nine fire ships bearing down on the shipping at the New Mole.

Amid a fierce cannonade from the Enterprise and the Panther, boat crews rowed toward the blazing vessels. British sailors hurled lines attached to grappling irons onto the fire ships. The boats turned six of the menacing hulks away, and they burned themselves out. Three more fire ships had aimed for the Panther, but one was diverted by boat crews and the other two drifted out to sea.

The wrecks of the fire ships were later plundered of their remaining undamaged timbers as well as their charred planks, providing a welcome source of firewood and charcoal. Captain John Drinkwater observed the persistent scarcity of firewood on the rocky and crowded peninsula. Much of the garrison’s supply was “wood from ships bought by the Government and broken up for that purpose, but which had so strongly imbued the salt water, that it was with the utmost difficulty we could make it take fire,” he wrote. A storm in December 1779 provided a welcome supply of driftwood after the waves washed up masses of shattered trees and logs onto the shore.

Eliott dealt with intensifying bombardment from land batteries and enemy gunboats. In November 1780 it was necessary to order a blackout. Eliott forbade lights to show, in his words, from house, barrack, or guard-house, towards the bay after 7 p.m. The governor detailed soldiers and civilians parties to dig up the town’s paved streets, using a special plow drawn by 80 men. The stones were dropped outside the line wall.

“[This was done] to prevent the havoc that would ensue from the explosion of the enemy’s shells,” wrote Ancell, “as the great weight they fall buried them under the surface of the ground, and when they burst, they scatter whatever is near them for 70 or 80 yards around.”

Hot shot and incendiary carcasses were potent artillery ammunition for Gibraltar. Furnaces resembling lime kilns were built near the various batteries to heat cannonballs to a glowing red, or even a white heat. In a pinch gunners could stack cold shot in the corners of a ruined stone house, bury it under a pile of wood and charcoal, and set it afire. The superheated iron could start fires when lodged in the timbers of a ship, or the wooden supports of a land battery.

Carcasses were large shells with three to five holes drilled in them and filled with varying mixtures of gunpowder, sulfur, and saltpeter along with flammable substances such as pitch, tallow, and turpentine. After impact, a carcass might spew its flames for 15 minutes. Carcasses were devastatingly effective against wooden buildings and ships, as well as the wooden fascines, gabions, and timbers of earthworks.

For decades, Gibraltar had enjoyed fresh fruit and meat from North Africa. In January 1781 the Sultan of Morocco sided with the Spanish, and closed his ports to the British. Three months later a fleet of relief ships escorted by Vice Adm. George Darby reached Gibraltar. Sotomayor and the Spanish commanders vented their frustration over Darby’s safe arrival with an intensified bombardment, but the garrison was reasonably well protected in sturdy fortifications, including tunnels dug into the Rock itself.

Some soldiers told stories of narrow escapes from death. “A bomb shell fell so near a sergeant of the garrison that the fuse set fire to his coat; happening to be running at the time, he continued his career with his clothes in an entire blaze; when out of danger from the bursting of the shell he stripped, and escaped completely unhurt,” wrote B. Cornwell, a civilian who witnessed the siege.

Another soldier “had the muzzle of his firelock closed, and the barrel twisted like a French-horn, by a shell, without injury to his person,” wrote Drinkwater. He noted another peculiar incident, when an enemy shell struck the Rock [of Gibraltar] and ricocheted “nearly at right angles with its range.” The shell exploded on the platform of a 32- pounder, “and a splinter cutting the apron on the gun fired it off: the shot took away the railing at the foot of the glacis, and lodged in the line-wall.”

Spanish land and naval artillery pounded the town of Gibraltar. Enemy shells set fire to supplies that were tucked away in the old Spanish church. Soldiers saved most of the food. Salvaged barrels of flour were taken to form emergency traverses inside the King’s Bastion. Barrels damaged by enemy fire were deemed fair game by the troops, who scooped out the flour and fried it into pancakes. The soldiers had emptied so many of the accessible barrels in the lower tiers that the weight of full barrels higher up brought about the collapse of the stacks. Other wood was found to build new traverses in the bastion.

“The streets of the town are like a desert, and almost every house burnt, or torn with shot and shells,” wrote Ancell. “In some parts the shot and broken pieces of shells are so thick, that in walking your feet does not touch the ground.” Walls and roofs crumbled as buildings collapsed into rubble.

Temptation lured soldiers through gaps in the crumbling walls into store rooms filled with rum, wine, and other coveted commodities. Some soldiers stayed drunk for several days, defying all orders to return to their duties. Captain Drinkwater knew of a band of miscreants who roasted a stolen pig with an extravagant fire of stolen cinnamon. Eliott restored order with countless floggings, and ordered executions for soldiers found guilty of looting, as well as those caught drunk or asleep on duty.

With their homes in ruins, townspeople took shelter near the southern end of the peninsula. Refugees clustered in a makeshift settlement, built of planks and timbers filched from ruined buildings in the town. The enemy’s land artillery could not reach the area, except when strong winds gave long-range projectiles an extra push, but the Spanish gunboats still menaced the sprawling shanty town. Cynical soldiers called it “Coward’s Town,” although eventually some of the garrison spent their off-duty time there. Later sailors serving ashore put up a camp near Europa Point, using spars and sails to make tents.

A slow trickle of deserters, including soldiers as well as apprentices and other civilians, tried to escape from Gibraltar. Some made it to the enemy lines; others disappeared. Ancell noted with great precision, that on March 7, 1781, a deserter bolted over the palisade. Besides hurling several blasts of grapeshot, “the several guards fired 1,143 musket shot at him…but he entered the Spanish lines in triumph.”

Occasionally the fate of a deserter was revealed by the discovery of a corpse afloat in the bay or a body lying limp and shattered after plunging from the heights of the Rock. One deserter drowned while apparently trying to swim from the Water Port. Sailors on a gunboat, “imagining some large fish had got foul of their cable, darted a harpoon into the body, but soon found out their mistake,” wrote Drinkwater.

Spanish deserters, some of them from Walloon regiments from Flanders, slipped into the British lines. Among them were spies sent to glean what close-up glimpses they could get of the defenses or to plant false information.

Minorca fell on February 5, 1782, severing a valuable supply line for Gibraltar. Except when provision vessels came in, the only fresh meat available was pork. It was “very indifferent and scarce, bring fed on the filth of the place,” wrote Ancell.

The scarcity of fresh citrus fruit and produce triggered an outbreak of scurvy. Ancell saw men so badly afflicted “they they have lost the entire use of their limbs, and represent the picture of decrepit old age.” Under Eliott’s orders, quartermasters served daily rations of one pound of onions to 10 men to combat the disease. They gave hospitalized victims two oranges or lemons a day.

Gibraltar’s batteries could slow but not stop the steady advance of the enemy siege works. By November 1781, another zigzag of the works ended within 700 yards of the Land Port. Choosing a new tack, Eliott launched a sortie against the enemy lines.

The sortie was begun in the utmost secrecy. Brig. Gen. William Ross led the advance, with a heavy concentration of sharpshooters and light companies, with gunners and artificers. Following in the second wave was Colonel William Picton with two regiments of foot. There was no chance of a deserter warning the enemy for none of the men knew about the attack until well after dark on November 26 when they were ordered to assemble.

Picton moved through the outer gates at 2 a.m. on November 27. His men found the attack a much easier task than expected. In designing their siege works, Spanish engineers planned well against artillery, but gave little consideration for infantry assaults. Spanish guns were deployed to fire upward into the British works, and could not be depressed to repel an infantry attack. Little more than a picket guard defended the works, and the redcoats easily swept them away.

Protected by their infantry, crews of British gunners and artificers went about spiking guns and setting the works on fire. Spanish guns further to the rear opened fire, and the guns on the Rock responded. The shells flew high overhead and did not interfere with the destruction of the captured works. As they withdrew, the British lit powder trains leading to the Spanish magazines. The explosions came when the raiders were safely out of the way. Some of the batteries burned for another four days before their last timbers were consumed.

The bold attack cost Eliott only four enlisted men killed, and the number of wounded came to just 25, with one man missing. Reportedly not a single musket nor any tools or implements were left behind, although a soldier of the 73rd Highland Foot reported the loss of his kilt.

Returning to their camps, many of the redcoats carried cabbages or cauliflowers. Their route across the sandy flats took them through the long-neglected gardens between the inundation and the Spanish lines. Swept by fire from both sides, the treasured vegetables had been out of reach until the sortie.

Captain-General Louis des Balbes de Berton, Duc de Crillon, assumed command of the siege in March 1782. A French-born noble who served in the Spanish Army, the Duc de Crillon had led the forces that captured Minorca. De Crillon stepped up the battle against Gibraltar. In late May 1782, 100 Spanish transport vessels loaded with reinforcements and supplies reached Algeciras. France sent a large transport fleet with 5,000 troops to join them in June. Soon 40,000 men with 266 guns and mortars faced the Gibraltar garrison.

The Spanish used their small gunboats and mortar vessels to great effect in constant bombardments. To counter them, the British cut down two store ships into gunboats, named the Vanguard and Repulse. Moored to the Old Mole, they served as additional batteries against the Spanish gunboats. In March 1782 several disassembled gunboats arrived on a merchant vessel, greatly enhancing the collection of British small craft available to serve in the bay.

Much more than traditional siege works would soon menace Eliott’s garrison. Colonel Jean Le Michaud D’Arcon, a French engineer, envisioned waterborne fortifications in the form of a line of 10 floating batteries. In May the British noticed workmen toiling aboard the dilapidated old vessels. D’Arcon would convert these creaking and clumsy hulks into what he hoped would be invincible floating fortresses, mounting from 10 to 26 guns each.

Each main deck of these so-called battering ships was covered with a casemate of heavy oak timbers. The casemate, resembling a huge cabin, had sloping roofs to deflect enemy shot. Rope netting held down a layer of animal hides, which were kept wet to prevent fire from catching hold in the timbers.

The port sides, which would face the British, were shielded with extra layers of oak timbers, packed with wet sand between the layers. Heavy bracing and large iron bolts secured the timbers.

D’Arcon shifted the ballast to the starboard to compensate for the weight of the guns and shielding. He had ordered work parties to trim the masts and rigging, but had instructed them to leave enough sail to maneuver the hulls. A fire suppression system of pipes and pumps, fed by onboard reservoirs, would squelch fires on the roof or sides before they spread out of control. On September 13, spread out in a line stretching over two-thirds of a mile, the battering ships slowly approached Gibraltar at 7 a.m. They halted in line 1,000 yards from the Gibraltar shore and dropped their anchors. Thousands of Spanish spectators lined the distant shores and hills, to watch from a safe distance as the panoramic spectacle unfolded.

British gunners opened fire with cold shot, and were shocked to see even 13-inch mortar shells bounce off the oaken roofs and sides of the floating batteries. Six hours of constant bombardment made no impression on the seemingly invulnerable hulls.

It took until early afternoon for the shot furnaces to turn the iron projectiles red hot. Hot shot was lifted from the heat with iron tongs, and carried to the guns in iron ladles with long handles. On that day the runners could not keep up with the desperate demand for ammunition. Finally, wheelbarrows loaded with sand ferried six hot, glowing rounds at a time.

The first signs that the heated shot was taking effect came at 2 p.m. that day. Smoke rose from the Talla Piedra and the Pastora, two of the largest battering ships.

British gunners stayed at their work, some slaking their thirst with the filthy water from the sponge buckets. One after another, the floating batteries slackened their fire. Masts and spars were shot away, leaving the damaged ships immobile. Abandoning their guns, sailors milled about on the roofs, hoping to be taken off the doomed ships. But ship’s boats rowing toward the battering ships were driven away by British fire.

By evening, the only firing from the battering ships was of signal rockets, sent soaring into the night skies to summon help. Captain Curtis led several longboats to pick up survivors. First one, then another, of the battering ships exploded. The blasts were powerful enough to “burst open doors and windows at the Naval Hospital,” wrote Captain John Spilsbury of the 12th Foot. By 4 a.m. six of the floating batteries were wrapped in soaring flames, casting a glare that lit the British batteries as if it were daylight.

Curtis returned to shore with 357 prisoners, including many wounded, taken from the wreckage or plucked from the water. They were a mixed lot that included Spanish sailors, marines, and soldiers, along with a few French soldiers and three chaplains.

When a party of Spanish prisoners trudged by the New Mole, they noticed that one of the shot furnaces was still in use. They saw scores of heated projectiles, some of them heated so much that they were melting. “They shrugged their shoulders and gave a piteous groan at what their eyes beheld,” wrote Ancell. “The wounded were carried into the Naval Hospital. Uninjured prisoners were confined at Windmill Hill; this height near the tip of the peninsula was about as far from the Spanish lines as one could get.”

The sun rose to reveal the devastation wrought upon the battering ships. By midday five of D’Arcon’s wooden fortresses had exploded. Three that had been burnt to the waterline still smoldered. The last two also were afire, set ablaze to prevent capture.

Land batteries and gunboats continued bombarding Gibraltar. Once again, British supplies were running short when Admiral Richard Howe shepherded another fleet of relief vessels to the garrison in October. This third resupply of the British put the capture of Gibraltar out of reach for many more months. With hints of the end of the Anglo-Spanish war, de Crillon’s siege began winding down.

Firing diminished, and work continued at a slower pace on the fortifications as soldiers departed for other posts.

Word arrived in February 1783 that the warring powers were close to signing a peace treaty. Eliott’s gunners fired a final shot on February 5. The siege, which had lasted for three years, seven months, and 12 days, ended the next day.

Eliott’s redcoats had successfully fended off the attacks of the Spanish officers and soldiers. To 258,387 rounds of incoming shot and shell, the Gibraltar garrison responded with 205,328,333 rounds of shot and shell. The British army distributed £30,000 in prize money to the soldiers of the garrison for the destruction of the floating batteries and the sale of a captured Spanish warship. British losses amounted to 536 who died from disease, 1,108 who were wounded in battle, and 43 who deserted. In contrast, the Spanish suffered approximately 100 killed and 200 wounded.

Eliott’s successful defense of Gibraltar was a tonic for the British, who had just lost their North American colonies. A grateful crown knighted Eliott. He was made Baron Heathfield of Gibraltar in 1783. Still serving as Gibraltar’s governor in 1790, he died in the free imperial city of Aachen in the Holy Roman Empire while traveling to restore his health. Great Britain made good use of Gibraltar as a major naval base in the Napoleonic era and during the world wars of the 20th century. A British Overseas Territory, it remains a valuable British strategic possession to this day.

Join The Conversation

Comments