By Michael E. Haskew

On the barren, windswept and war-torn Korean peninsula, the autumn of 1950 brought United Nations forces to the brink of total victory—and complete disaster.

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur’s brilliant amphibious operation at Incheon had turned the tables on the invading communists and returned the capital city of Seoul to South Korean president Syngman Rhee just three months after North Korean forces had crossed the 38th parallel. Seizing the offensive, the American-led UN armies rushed forward, crossing into North Korea and occupying the enemy capital of Pyongyang by mid-October. Flush with victory, MacArthur promised to conclude the fighting by Thanksgiving and bring his troops home by Christmas.

In Washington, President Harry Truman’s administration took warnings from communist China seriously—fearing that a widening of the Korean War meant Chinese intervention was imminent. MacArthur characteristically downplayed these concerns, and the general ordered his forces to continue northward toward the Yalu River and the Chinese frontier.

As commander of UN forces in Korea, MacArthur was confident of victory. But in this case, the brash and often arrogant leader had grossly miscalculated.

On October 19, the communist Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) attacked, intent on pushing the UN forces out of North Korea. In November, an avalanche of Chinese troops had put the UN armies to flight. “They swarmed over the hills, blowing bugles and horns, shaking rattles and other noisemakers, and shooting flares in the sky,” recalled American soldier Julius W. Becton. “They came on foot firing rifles and burp guns, hurling grenades, and shouting and chanting shrilly. The total surprise of this awesome ground attack shocked and paralyzed most Americans and panicked not a few.”

In the week-long Battle of the Ch’ongch’on River, the PVA and its North Korean cohorts forced a general UN retreat. Following that victory, the communists recovered all territory north of the 38th parallel. Advancing into South Korea, communist forces occupied the capital city of Seoul during the first week of January 1951. The shock of the communist onslaught had left MacArthur temporarily stunned, and as the debacle unfolded, he admitted, “We face an entirely new war.”

Although losses had been heavy and morale reached its nadir among the American and UN forces in the wake of the battlefield defeats, MacArthur and Gen. Matthew Ridgway, commanding the U.S. Eighth Army, assessed the situation and marshaled their forces to launch a pair of counteroffensives. Operation Killer, February 20-March 6, 1951, wrested the initiative from the communists and succeeded in driving back the enemy from territory south of the Arizona Line, which stretched from Yangpyeong to Hoengseong. Operation Ripper followed immediately with the objective of reaching the Idaho Line, just south of the 38th parallel. Ripper achieved its objective, and Seoul was liberated again in mid-March.

Still, the Chinese were determined to press forward, retaking Seoul, and destroying UN forces that opposed them, particularly on a direct route to the South Korean capital.

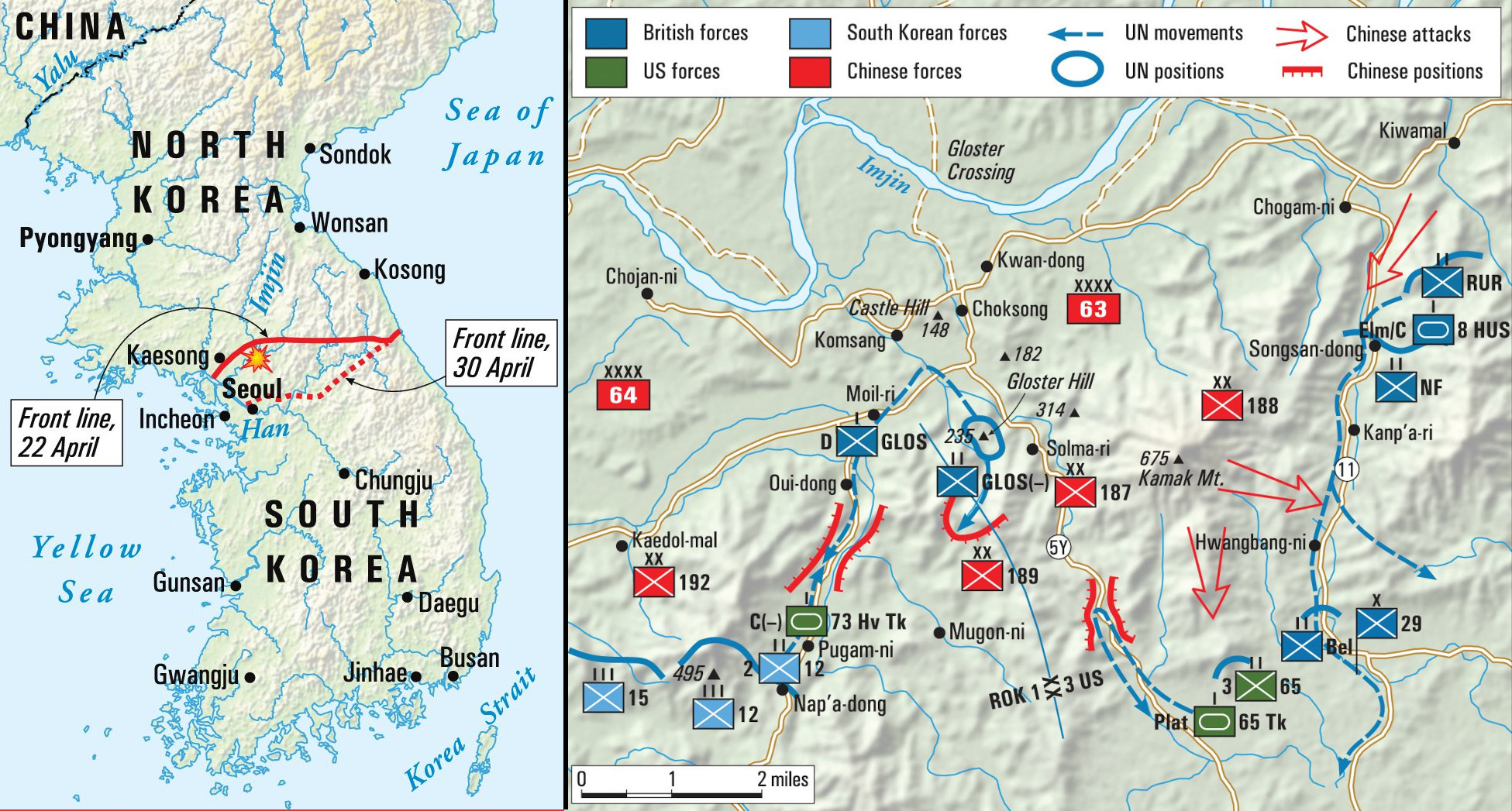

With more than 300,000 troops still in the field, Field Marshal Peng Dehuai, the senior Chinese commander, believed his reinvigorated offensive plan would accomplish that goal. Two full army groups were available to potentially overwhelm the UN positions around the southern Imjin River north of Seoul. Elements of the XIX Army Group were ordered to attack the U.S. 3rd Division and the South Korean 1st Division along the Imjin River where the waterway turned northward, while the 63rd Army, composed of three divisions, was to hurl itself against the British 29th Brigade just to the west. The three divisions of 63rd Army—the 187th, 188th, and 189th—included nearly 30,000 soldiers.

Meanwhile, the UN forces, primarily I Corps of the U.S. Army and attached allied units, had taken up defensive positions that stretched just across the 38th parallel and then to the Hwacheon Reservoir and the Imjin in its northward course. Their thin defensive belts were known, respectively, as the Kansas Line and the Utah Line. The I Corps perimeter stretched west to east with the 29th Brigade inadequately occupying a 12-mile expanse of rugged country—British Brigadier Thomas Brodie was obliged to concentrate his forces on tactically vital high ground, leaving substantial gaps between the defensive positions. A veteran of combat in the China-Burma-India theater during World War II, Brodie recognized the precarious situation.

The 29th Brigade had already absorbed significant combat losses, and during the Chinese onslaught against Seoul just weeks earlier Brodie had demonstrated his willingness to fight tenaciously, declaring to his command, “At last after weeks of frustration we have nothing between us and the Chinese. I have no intention that this Brigade Group will retire before the enemy unless ordered by higher authority to conform with general movement. If you meet him you are to knock hell out of him with everything you’ve got. You are only to give ground on my orders.”

Arriving in Korea the previous November as a component of the British commitment to the Korean Conflict that eventually topped 90,000 troops, the 29th Brigade had participated in the advance toward the Yalu and then in the withdrawal to the south during the Chinese winter offensive. As it stood at the Imjin in mid-April 1951, the stout-hearted brigade included the 1st Battalion Royal Northumberland Fusiliers under Lt. Col. Kingsley Foster, 1st Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles led by temporary commander Maj. Gerald Rickford, the 700-man Belgian Brigade, and the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment commanded by Lt. Col. James Power Carne. Supporting units consisted of 45 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery, with its 25-pounder guns, 170 Independent Mortar Battery, Royal Artillery, with heavy 4.2-inch mortars, 55 Squadron Royal Engineers, and C Squadron, 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars with its superb Centurion Mk III main battle tanks.

Although the 29th Brigade positions were believed by higher echelon commanders to be relatively secure, they were also acknowledged as vulnerable in case of a major Chinese attack. Such a risk was mitigated by the anticipation that this section of the front might only be occupied for a brief time; however, while an imminent resumption of heavy Chinese attacks did not seem likely, the buildup of enemy forces that preceded the storm of the looming communist spring offensive appears to have proceeded largely unnoticed. Brigadier Brodie distributed his forces as best he could, but no appreciable mine fields, barbed wire entanglements, reinforced bunkers, or shelters for protection against enemy artillery had been constructed.

On Brodie’s left flank, separated from the South Korean 1st Division by a mile of open ground, the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, popularly known as the “Glosters,” covered a shallow ford of the Imjin. Swinging northeast, the Fusiliers took up positions two miles distant from the Glosters, while the Belgian Brigade occupied the high ground of Hill 194 on the brigade’s right flank. The Belgians, commanded by Lt. Col. Albert Crahay, constituted the single UN element north of the Imjin; their only route of evacuation if overrun by communist forces would be across a pair of pontoon bridges a half-mile apart that joined Route 11, the vital supply and communication line that the 29th Brigade had to defend at all costs. The Ulster Rifles deployed as a reserve along Route 11.

After lengthy preparations, the Chinese juggernaut filtered into its jump-off positions during the month of April. First contact with the UN defenders along the Imjin occurred during the night of the 21st when a Glosters listening post picked up some movement.

“The three of us settled down for a long wait,” recalled Drummer Tony Eagles, years after the engagement. “It was a nice clear night and gave us a good field of vision for about half a mile east and west. We had decided that we would have two on observation and the other would sit with the phone, changing each hour. Sometime within the next three hours, perhaps about 2200, I whispered to ‘Scouse’ that I thought I saw movement on the other side of the river. He alerted George Cook who reported back to the adjutant. After a while we could discern 14 figures that, by virtue of their khaki uniforms and rice bags slung like a bandolier, could only be Chinese troops.

“Suddenly, the sky was lit up as the Royal Artillery sent up floating flares requested by the adjutant,” Eagles continued. “We could see the others quite closely as they reached the point opposite us. The adjutant told Corporal Cook that they must not be allowed to cross. ‘Scouse’ and I decided we would let them get about halfway across, and then fire. If they succeeded in getting close enough, we would use our grenades.”

That probing foray was the prelude to the primary communist assault that began less than 24 hours later. In the predawn darkness of April 22, the vulnerable Belgians ensconced on Hill 194 were alerted to a Chinese patrol attempting to skirt their positions and move eastward toward the two bridges across the Imjin. This early contact occurred with one of several patrols from the Chinese 187th Division intended to find and exploit the gaps in the UN defensive line. In response to the mounting threat, Brodie dispatched a motorized element of the reserve Royal Ulster Rifles to secure the bridges. However, this detachment was ambushed on Route 11 by the Chinese near the crossing at Hant’an and virtually destroyed.

As the battle intensified the Belgians became fully engaged and by the first rays of daylight they faced the real prospect of being cut off from the main body of the 29th Brigade. A large Chinese force followed the earlier patrols and then split— with some units joining the attack on the Belgians on Hill 194, while others crossed the Imjin on the pontoon bridges and mounted an intense assault against the Northumberland Fusiliers who were positioned in a rough square across the heights of Hill 257 and other high ground. On the Fusiliers’ right flank, Z Company occupied the right rear section of the line and bore the brunt of these initial assaults just south of the river and in the direct line of the intended communist advance southward toward Seoul.

More Chinese troops soon forded the Imjin downstream from Hill 257 and engaged the left flank of the Fusiliers’ positions at Hill 152, where X Company had occupied the left front corner of the box-like defenses that extended nearly to the south bank of the river. In rapid succession, Company X was compelled to fall back from Hill 152 and heavy Chinese attacks breached the line of Company Z at Hill 257. Company Y, at the right front corner of the British box, was not under direct attack but was soon flanked by Chinese troops filtering past on both sides.

Just after dawn, the Chinese committed reinforcements from the 188th Division and effectively doubled the strength of the thrust against the 29th Brigade. A Belgian patrol confirmed the grim news that the enemy controlled both bridges across the Imjin with direct fire on the approaches from Hill 257.

Word of the deteriorating situation reached the headquarters of the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, and Gen. Robert H. “Shorty” Soule dispatched a company of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment along with two platoons of the attached tank company. This force reached the bridges and found that the Chinese were not in direct possession of them; however, enemy mortar and small-arms fire was heavy, casting doubt on the success of any further movement by infantry or light armored vehicles. The tank platoons split up, one taking the enemy on the slope of Hill 257 under fire and the other moving on to Hill 194 to bolster the Belgians.

As the morning of April 23 wore on, Brigadier Brodie became increasingly concerned that the Chinese attacking the Northumberland Fusiliers might roll down Route 11 from the vicinity of Hill 257. He ordered the Fusiliers back to high ground about two miles from Hill 257 and bordering the roadway while the Ulster Rifles came up alongside to the east. Although the gap between Brodie and the Belgians widened, just as worrisome was the two-mile gap between the Fusiliers and the Glosters to their left. Reports indicated that Chinese infantry was already operating in this gap, and Brodie asked Soule for help again. In response, the 3rd Division commander sent the 1st Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment to plug the hole between Brodie’s central and left flank positions.

On the left of the 29th Brigade, the Glosters had been heavily engaged through the night of the 22nd. Companies A, B, and D had,respectively, occupied Hills 148, 182, and 144—all spurs that sloped toward the edge of the Imjin— and the positions crossed Route 5Y about 1.5 miles south of the river. Company C was placed in a reinforcing position at Hill 314 to give the defense some depth. The entire position was in the shadow of Hill 675 (Karnak Mountain), the dominant terrain feature in the area. Company G was located just above the village of Solma-ri, and Lt. Col. Carne positioned his mortars to cover Route 5Y as it twisted through the small adjacent valley.

Carne knew that the Chinese were aware of the ford he had been ordered to protect, especially since his engineers had placed buoys to mark it just hours earlier. He sent 16 men of Company C forward to occupy buildings near the crossing and lie in ambush to slow the Chinese. Under the command of Lt. Guy Temple, this intrepid patrol watched as seven enemy soldiers stepped into the waters of the Imjin in the pale moonlight at about 10 p.m. They cut down all seven men, then fought off three more crossing attempts before their ammunition ran low and they withdrew, leaving 70 dead Chinese scattered along the shore.

Just after the withdrawal of Temple’s small force, which had sustained no casualties, a battalion of the Chinese 559th Regiment (187th Division) did begin successfully fording the Imjin while also crossing on a submerged bridge about a mile and a half west that had escaped British detection. While this transit was in progress, British artillery opened up, exacting a heavy toll on enemy troops at the ford. The Chinese advancing from the west, however, were unopposed until they attacked Company A on Hill 148.

Outnumbered at least six to one, the 58 men of Company A fought gamely on what became known as Castle Hill due to the remnants of an ancient structure that served to anchor their defense near the crest. Not far away, Company D held its ground at Hill 182 but lost a number of men in the fighting. Company B was relatively unscathed after briefly skirmishing with Chinese patrols along the slope of Hill 144.

Carne was painfully aware that he could not pull his Glosters back further without exposing the flank of the South Korean 1st Division, but the situation became more perilous after the Chinese took the crest of Castle Hill about 7:30 a.m. Company A fought on gamely but failed to regain the key position. During one attempt to retake the crest, Lt. Philip Curtis, commanding No. 1 Platoon of 1st Battalion and on loan from the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, responded to an order to counterattack.

Curtis led from the front, and his platoon made initial headway before a barrage of Chinese grenades and a stream of small-arms fire brought them to a halt. Curtis ordered his men to provide covering fire and charged alone at the enemy machine-gun emplacement that was most troublesome. He was seriously wounded but managed to return to cover. In great pain and bleeding profusely, Curtis would not be dissuaded from making a second attempt. He gathered himself, rose, and charged again. Approaching within a few yards of the machine-gun emplacement, he was riddled with Chinese bullets but managed to toss a single grenade that silenced the enemy weapon.

Glosters adjutant Captain Anthony Farrar-Hockley witnessed the 24-year-old officer’s heroics and later wrote, “…Phil has gone: gone to the wire, gone through the wire, gone towards the bunker. The others come out behind him, their eyes all on him. And suddenly it seems as if, for a few breathless moments, the whole of the remainder of that field of battle is still and silent, watching amazed, the lone figure that runs so painfully forward to the bunker holding the approach to the Castle Site: one tiny figure, throwing grenades, firing a pistol, set to take Castle Hill…But the machine gun in the bunker fires into him: he staggers, falls, and is dead instantly; the grenade he threw seconds before his death explodes after it in the mouth of the bunker. The machine gun does not fire on three of Phil’s platoon who run forward to pick him up; it does not fire again through the battle: it is destroyed; the muzzle blown away, the crew dead.”

Even though the attempts to recapture the crest of Castle Hill were unsuccessful, Curtis was honored with a posthumous Victoria Cross, the British Empire’s highest decoration for valor under fire. The medal was presented to his family on July 6, 1954, and is now on display at the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry Museum in Bodmin, Cornwall.

Carne ordered his advanced companies to fall back to Solma-ri, conceding gains to the Chinese, while air strikes, artillery, and mortars covered the withdrawal. Later in the day Company A, well understrength after its fight at Castle Hill, occupied Hill 235 west of Route 5Y, while Company D reached Flat Top Hill to the east with Companies B and C in line across the roadway. The Chinese were subjected to heavy artillery fire, which checked their advance temporarily, allowing time to remove casualties and perhaps call up further reserves of their 63rd Army.

Amid a general adjustment of UN forces along the Kansas Line and elsewhere, Brigadier Brodie addressed the extrication of the Belgians from the area of Hill 194, the so-called “Imjin Angle.” The U.S. 65th Infantry Regiment repositioned and offered some cover along Route 33 above Hant’an as the plan for the Belgian withdrawal was put together. Although Brodie had proposed to General Soule that the Belgians destroy their vehicles and withdraw on foot along the rearward side of Hill 194, Soule asserted that the bridges could be utilized as a result of a counterattack by the 1st Battalion, 7th Infantry and the Philippine 10th Battalion Combat Team. This attack, launched at 2 p.m., targeted Hill 257 and Route 11 to the slopes of Hill 675.

Although the attack made little progress during the next four hours, the Belgian withdrawal from Hill 194 began with its opening advance. By 6:30 p.m., the Belgians were successfully out of immediate danger, their last vehicle crossing the Imjin. Belgian vehicles and foot soldiers made rendezvous near the junction of Routes 11 and 33 while those units that had facilitated their movements returned to earlier defensive positions along the Kansas Line.

Meanwhile, Carne’s repositioned Glosters had benefited from a relatively quiet day in the Solma-ri area. Enemy patrols had clashed with the Glosters’ own security patrols, particularly in the zone of Company B on the extreme right flank. However, the Chinese were diligently augmenting their strength south of the Imjin as elements of both the 63rd and 64th armies streamed in to threaten the front and flanks of Carne’s command. Some of the Chinese reinforcements probed the 1st South Korean Division’s perimeter and lost heavily to counterattacks from the infantry and tanks of the 73rd Tank Battalion. These clashes ebbed and flowed from late morning to mid-afternoon on the 23rd, and estimates of Chinese casualties topped 3,000.

Nevertheless, persistent Chinese advances began to encircle the Glosters on Hill 235. Chinese forces were observed crossing at the Imjin ford nearby and, though harassed by British mortar and artillery fire, large numbers managed to reach southerly positions. To the northeast, elements of the 187th and 189th Divisions exploited the gap between the Glosters and the Northumberland Fusiliers. By afternoon, the Chinese had reached Route 5Y and launched an attack against the vital Gloster supply route. Therefore, Carne concluded that his positions at Hill 235 and Solma-ri were completely surrounded.

Chinese attacks that stretched into the early hours of April 24 further depleted the ranks of Company A, which by now was roughly half its original strength with every one of its officers either dead or wounded. A platoon of Company D was shredded in a vicious fight as the formation fell back to Hill 235. Company B was outnumbered 18-to-1 as the Chinese hurled themselves against its thin line half a dozen times. The Company B Glosters held, their commanding officer even requesting artillery fire on his own positions to break the back of one enemy assault, until just after 8 a.m. on the 24th. By then, only 20 infantrymen from Company B were left to reach their fellow Glosters at Hill 235. Meanwhile, the Chinese 188th Division mounted strong attacks against the Royal Ulster Rifles and the Northumberland Fusiliers on the right of the 29th Brigade.

Exhausted, short of ammunition, and facing overwhelming odds, the Glosters at Hill 235 were on the cusp of a harrowing fight for survival, one that would test their mettle to the utmost and etch their names in the annals of the British military as one of the most heroic stands in its illustrious history.

Chinese spearheads penetrated the now four-mile gap between the Glosters and Northumberland Fusiliers, and the Philippine 10th Battalion Combat Team was ordered forward along with the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars, the former committing four M24 Chaffee light tanks to the fight and the latter six Centurion Mk. IIIs. This support foray, however, stalled 2,000 yards from Hill 235 as Route 5Y narrowed to the extent that the Centurions could negotiate it no further. The lead tank had been disabled, blocking further progress—though two Centurions did squeeze past the crippled M24 while Filipino infantry engaged in a brisk exchange of fire with Chinese soldiers on the slopes of a defile along both sides of the road before pulling back.

Still full of vigor and command presence, Carne sent a message to Brigadier Brodie that aptly described the Glosters’ desperate situation. “I understand the position quite clearly. What I must make clear to you is that my command is no longer an effective fighting force,” he wrote. “If it is required that we shall stay here, in spite of this, we shall continue to hold.”

Indeed, by the afternoon of the 24th the Glosters’ numbers had dwindled to a mere 350 men capable of firing a rifle. But, stay they did, covering themselves in glory at a tremendous price.

Carne sent a party back to the Glosters’ former headquarters in the valley, and some vital supplies and ammunition were recovered. The commander then directed mortar fire on the remaining stores to prevent them falling into the hands of the Chinese. Carne also consolidated his positions at Hill 235 across the long, thin crest of the high ground, taking advantage of the steep terrain to help slow the expected Chinese attacks. When the enemy came forward, concentrated Gloster fire threw them back several times, but eventually a few Chinese soldiers did reach the crest from the northwest. The Glosters rallied and repulsed the Chinese from the summit. Other enemy attacks were broken up by Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star fighter bombers that decimated Chinese troop concentrations.

Two more attempts to reach the embattled Glosters had failed by the early hours of April 25, and the larger tactical situation dictated that all I Corps forces were to execute Plan Golden A—withdrawing to a new line of defense entirely south of the Imjin and effectively leaving the Glosters to their fate. Even as Chinese pressure was unrelenting, Carne was allowed to choose whether to surrender to the communists or attempt to break out of the encirclement. The gallant officer passed the word that his men were allowed to attempt to reach the safety of the UN lines as they could.

Captain Mike Harvey led a group of soldiers in a desperate bid to avoid capture. In his book, The War in Korea: The Battle Decides All, Harvey later wrote of its concluding moments, “We then saw UN tanks ahead, and crawled and ran in turn eagerly ahead and got within 500 yards of them, but they mistakenly took us for Chinese and opened fire with HMGs and 75mm cannon, and our six leading men fell. Shouts from the rear of our thinning column told us clearly that Chinese were in pursuit and shooting and bayoneting the men at the tail, mercilessly killing what were now, unarmed soldiers. We were now compressed between the Americans and Chinese…The tanks, suddenly aware of their error, ceased firing at us and redirected everything they had onto the Chinese along the ridge…We reached the tanks and took cover behind them, using them as shields, and moving when they did, to keep them between us and the intense fire which still poured onto the tanks, rattling like kettle drums from the strike of the bullets.”

When Harvey and his followers began their descent of Hill 235, which would forever forward be known as Gloster Hill, they numbered 104 men of Company D. Only 46 managed to reach the safety of the UN line. Harvey received the Military Cross for valor.

Despite the described incident of friendly fire, the presence of UN armor had been critical to the resistance against the Chinese spring offensive. While the Glosters held their position on Hill 235 for two critical days, the Centurions of the 8th Hussars, armed with QF 20-pounder (84mm) main guns and .30-caliber machine guns, fought to cover withdrawal and repositioning movements. At one point, swarms of Chinese soldiers had gotten among the tanks, attempting to pry their hatches open or disable them with grenades. The crews of the buttoned-up Centurions had actually turned their machine guns on one another, slaughtering the Chinese. In another incident, the Centurions had caught three Chinese platoons in the open as they crossed the Imjin riverbed, chewing them to pieces.

One Centurion commander recalled, “After about three hours of continuous firing, my machine gun barrel needed changing; my recoil system was so hot that it wouldn’t run back and my loader/operator Ken Hall had fainted with the continual hard work and fumes.”

When the fight at the Imjin River was over, I Corps commander Gen. John O’Daniel praised the 8th Hussars: “In their Centurions, the 8th Hussars have evolved a new type of tank warfare. They taught us that anywhere a tank can go is tank country, even the tops of mountains.”

With the endgame at Hill 235, only Harvey’s few had made good their escape from the Chinese encirclement. Carne and 459 Glosters were captured, and the beleaguered battalion had lost 620 men killed, wounded or captured—roughly 57 percent of the 29th Brigade’s 1,091 casualties. In stark testament to the ferocity of the 29th Brigade defense and the heroism of the “Glorious Glosters” as they came to be known, the Chinese and North Koreans suffered more than 10,000 dead, wounded or taken prisoner.

The costly fight at the Imjin had slowed the communist spring offensive of 1951 such that United Nations forces were able to stabilize the front and ultimately thwart the enemy bid to recapture the South Korean capital. The Imjin engagement is regularly referred to as the “battle that saved Seoul.”

Carne survived the war, enduring months in communist captivity and lengthy periods of solitary confinement. He was released in September 1953 and a month later awarded the Victoria Cross for exceptional bravery and leadership in the most adverse of circumstances. His citation reads in part, “Throughout the time Colonel Carne moved among the whole battalion under very heavy mortar and machine-gun fire, inspiring the utmost confidence and the will to resist among his troops. On two separate occasions, armed with rifle and grenades, he personally led assault parties which drove back the enemy and saved important situations. His courage, coolness and leadership was felt not only in his own battalion but throughout the whole brigade.”

Carne retired from the British Army in 1957 with the rank of colonel and died at age 80 in 1986. His Victoria Cross is on display today at the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum.

Further recognition of the heroism of the 29th Brigade at the Imjin River was evidenced with the award of the U.S. Presidential Unit Citation to the 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, C Troop, 170 Independent Mortar Battery, Royal Artillery, and the Belgian Battalion.

Captain Farrar-Hockley was one of four recipients of the Distinguished Service Order. Farrar-Hockley rose to the rank of general, honored with the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire and as Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, and serving as commander-in-chief of NATO forces in Northern Europe. He died in 2006 at age 81, always remembering those difficult days of April 22-25, 1951.

In his post-war history titled The British Part in The Korean War, Farrar-Hockley wrote of the 29th Brigade’s conspicuous gallantry, “Brigadier Brodie entered into the Brigade operations log in a moment of high emotion, ‘No one but the Glosters could have done it.’ This was flattering but not true. The other members of the brigade fought no less well. Neither they nor the Glosters sought to be heroes; only to acquit themselves honourably and competently, one among another. That is the best of the soldier’s calling.”

At the foot of barren Gloucester Hill, a memorial was erected in 1957, commemorating the heroism of the fighting men who had struggled so tenaciously there. Four plaques, sculptures of the Glosters’ beret and several of its soldiers on vigilant patrol, a memorial wall and garden mark a place of sacrifice and courage unsurpassed.

Quite a story. Had two tours, 39 months, in Korea myself.