By Pedro Garcia

War was a tonic for Phil Sheridan. “He was a wonderful man on the battle field,”one of his brother Union officers recalled, “and never in as good humor as when under fire.” Sheridan was a throwback to an earlier age of warfare, a warrior who lived for the comradeship of camp and field. But there was nothing romantic about his view of war. Sheridan, like his fellow Ohioan William Tecumseh Sherman, believed that “war is simply power unrestrained by constitution or compact.”

The trajectory of Sheridan’s career traced back to his childhood in Somerset, Ohio. Things military were all the rage among Somerset’s boys. Next to Christmas, the Fourth of July was the most important day of the year. Every year, Somerset’s one Revolutionary War veteran would be trotted out to greet the crowd. As the town’s cannon barked its salute and the crowd cheered wildly, young Sheridan would gawk at the old warrior. “I never saw Phil’s brown eyes open so wide or gaze with such interest,” remembered a friend, “as they did on this Revolutionary relic.”

The son of Irish immigrants, Sheridan managed to secure an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated in the bottom third of his class in 1853. He spent the next eight years on frontier duty with the Army. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he was assigned to the Department of the Missouri, under the watchful eye of Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck. By December 1861, Sheridan had sufficiently impressed his fussy commander to be named chief quartermaster and commissary of the Army of Southwest Missouri, then organizing for the Pea Ridge campaign. But he soon grew restless with administrative work, and in April 1862, he found field duty with the topographical engineers accompanying Halleck’s army at the siege of Corinth, Mississippi.

The Rise of “Little Phil”

Sheridan’s slow but steady rise continued when he was appointed colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry on May 25, 1862, and gained a decisive victory over a much larger enemy at the Battle of Booneville, Mississippi. Shortly thereafter, he was made a brigadier general and given command of the 11th Infantry Division of the Army of the Ohio. He led his troops with a keen tactical eye and bulldog tenacity at the bloody Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, in October and 10 weeks later at the even bloodier Battle of Stones River, Tennessee, where his skillful maneuvering and stubborn defensive stand helped save the army and earned him a promotion to major general.

At the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, Sheridan lost over a third of his division and, like many of his fellow Union generals, was driven from the battlefield. However, that November he redeemed himself by helping to lead the impulsive charge up Missionary Ridge, which ended the Confederate siege of Chattanooga. His combativeness caught the eye of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the new commander of Union forces, and when Grant was promoted and brought east in March 1864, he brought Sheridan with him to head the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

The man known to his troops as “Little Phil” did not cut an impressive physical figure. No more than five feet, five inches tall, he possessed inordinately long arms and short legs. A fellow officer opined that he “certainly would not impress one by his looks any more than Grant does. He is short, thickset, and common Irish-looking. Met in the Bowery, one would certainly set him down as a b’hoy.” Abraham Lincoln described Sheridan, with only slight exaggeration, as “a brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch, he can scratch them without stooping.”

The most striking feature of the bantam-sized general was his restless energy, what one soldier described as “nervous animation.” Under Sheridan’s bold leadership during the Overland campaign, the self-confidence and efficiency of the Cavalry Corps increased steadily until it came to regard itself as invincible. Previously cautious and unsure of themselves, the blue-clad horsemen under Sheridan became hell-for-leather cavalrymen, inflicting crippling losses on the enemy cavalry and even killing the iconic Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern, Virginia, in May 1864.

Give the Enemy No Rest

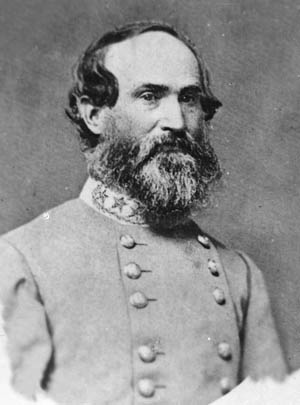

By the war’s fourth summer, the military situation in Virginia was one of stalemate. In an effort to break the logjam and loosen Grant’s death grip on Petersburg, General Robert E. Lee made a bold gamble. Refashioning a strategy he had used successfully in the spring of 1862 (with the invaluable assistance of the late Lt. Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson) Lee sent Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s II Corps to sweep Union forces from the Shenandoah Valley and menace Washington, D.C. After brushing off ineffective resistance, Early drove down the valley unopposed, crossed the Potomac into Maryland, and threw a scare into Lincoln and the Union capital.

Initially, Grant showed little interest in Early’s raid, but he soon realized that as long as the Confederacy maintained an active presence in the valley, Washington itself would never be safe. Accordingly, he organized the Middle Military Division to deal with the difficulty, creating the Army of the Shenandoah. On August 6, Sheridan took command of the new force.

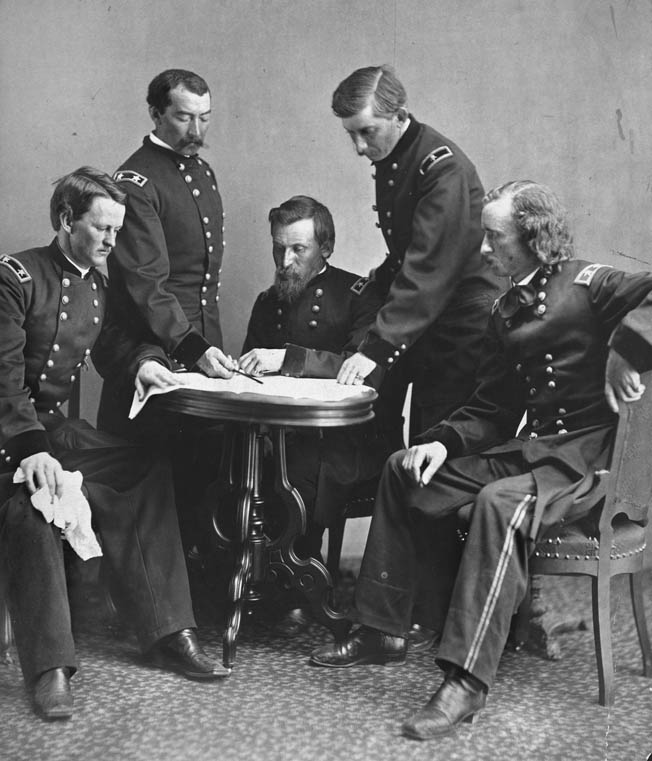

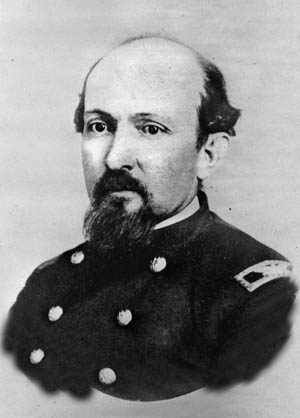

The 40,000-man Army of the Shenandoah was an amalgamation of three infantry corps, a cavalry corps and a dozen field batteries. The foundation of the army was the VI Corps of the Army of the Potomac. The largest corps, it comprised three divisions with a solid reputation for reliability and steadfastness. The VI Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, was the mirror image of his sturdy veterans. The two divisions of the XIX Corps, fresh from the Department of the Gulf, were far behind the VI Corps in discipline and efficiency. Many of the troops had seen only garrison duty, and all had been badly handled in the recent ill-fated Red River campaign. The oldest of the corps commanders, 52-year-old Maj. Gen. William Emory, led the XIX Corps.

The third infantry command was euphemistically called the Army of West Virginia, but was designated as the VIII Corps for the upcoming campaign. The troops had been whipped by Early at the Second Battle of Kernstown two months earlier and were eager for revenge. Sheridan’s old West Point classmate and close friend. Maj. Gen. George Crook, commanded the VIII Corps. Rather than appointing a chief of artillery, Sheridan kept the batteries with the infantry corps. Six were attached to Wright’s command, and three each supported Emory and Crook.

Sheridan’s orders called for him to defeat Early’s army, close off the natural warpath into the North, and eliminate the Shenandoah Valley as a vital productive region to the Confederacy. Grant told him bluntly: “The people should be informed that so long as an army can subsist among them, recurrences of these raids must be expected, and we are determined to stop them at all hazards. Give the enemy no rest. Do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. Carry off stock of all description so as to prevent further planting. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.”

Lee, determined to up the ante, sent Early another two divisions of cavalry and infantry, as well as a battalion of artillery. Grant instructed Sheridan to remain on the defensive. For the ever aggressive Sheridan, this had the effect of putting a choke collar on a pit bull. But there was a political element to Grant‘s thinking. In his memoirs he explained: “I had reason to believe that the administration was a little afraid to have a decisive battle fought at this time, for fear it might go against us, and have a bad effect on the November elections.”

Early’s Miscalculation

Sheridan shifted his position from Cedar Creek to Halltown, resting his flanks on Opequon Creek and the Shenandoah River and offering the Confederates no opportunity for a surprise attack. Early, for his part, conducted a vigorous feeling-out process, probing Sheridan’s defenses at various points but failing to uncover any significant weaknesses. “My only resource was to use my forces so as to display them at different points with great rapidity,” Early said later, “and thereby keep up the impression that they were much larger than they really were.”

As August gave way to September, it became clear that the shadow boxing could not last for much longer. Lee was the first to yield in the war of nerves. Grant’s unrelenting pressure on the Confederate lines compelled the Confederate commander to recall his recent reinforcements, leaving Early only Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry. With the help of an alert Union spy, Winchester schoolteacher Rebecca Wright, Sheridan soon learned of the weakening of Early’s army. Inexplicably, Early now became dangerously overconfident. “The events of the last month,” he wrote, “have satisfied me that the commander opposed to me was without enterprise, and possessed an excessive caution which amounted to timidity.” It was a serious error of judgment, and one that induced Early to rashly divide his force. On the 17th, he accompanied the infantry divisions of Maj. Gens. John Gordon and Robert Rodes to Martinsburg to break up nonexistent Union railroad crews. It was, one Confederate scoffed, a “wild goose chase.”

While Early was off chasing phantom railroad repairers, Grant paid Sheridan a brief visit in the field. The two Union generals met under the shade of a large oak tree at Charlestown, where Sheridan unveiled a plan calling for a double envelopment, a classic maneuver that depended on strict adherence to a fixed timetable. Grant gave Sheridan the go-ahead. “Go in,” he told him.

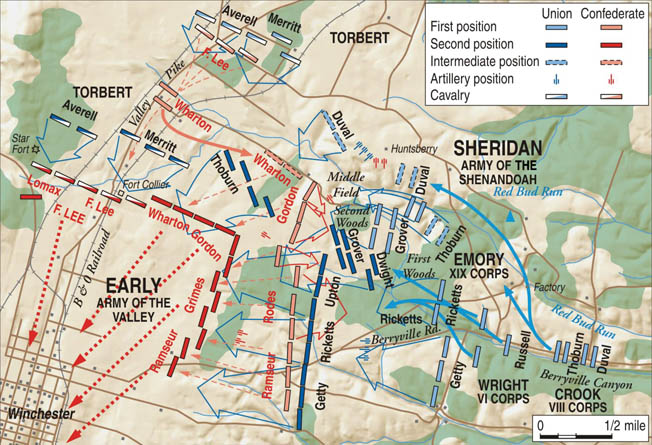

Beating the Confederates to Berryville Pike

Sheridan immediately set his plan into motion. Four miles east of Winchester, steep-banked Opequon Creek snaked its way northward down the Shenandoah Valley to empty into the Potomac River six miles south of Williamsport, Maryland. The creek, with numerous fords, was the boundary line between the two armies, Sheridan’s on the east, Early’s on the west. At the point where the Berryville Pike crossed, the creek became a veritable canyon, running for over two miles before spilling into open farmland.

Sheridan’s scouts informed him that Early’s troops were stretched out and separated “like a string of glass beads with a knot between each one.” The key to victory would lie in Sheridan’s ability to strike Early’s separated divisions before they could reunite astride the Berryville Pike. The battle plan assigned to Brig. Gen. James Wilson’s cavalry division the crucial role of securing the Berryville Pike, clearing the canyon, and opening the way for the VI and XIX Corps to reach maneuverable terrain. Then, according to the plan, Wilson’s division would shift to the left to secure the army’s south flank. Meanwhile, the cavalry divisions of Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt and Maj. Gen. William Averell would circle around Early’s left and pitch into his rear. Finally, the VIII Corps would advance beyond Wilson’s cavalry across the Valley turnpike south of Winchester and block Early’s expected retreat south. The flaw in Sheridan’s scenario was his misjudged plan to funnel 20,000 soldiers and trains through the bottleneck of Berryville Canyon.

Traffic Jam in the Canyon

About 4:30 am on the 19th, Wilson’s troopers splashed across Opequon Creek at Spout Spring, moving rapidly west to drive in the Confederate pickets under Maj. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur. The pickets, from the 23rd North Carolina Regiment, recoiled from the quick-firing Federals and withdrew to their earthworks, leaving behind their fatally wounded colonel, Chares C. Blackmall. Ramseur, reacting quickly, dispatched Brig. Gen. John Pegram’s five Virginia regiments to support Brig. Gen. Robert D. Johnston’s brigade. As the red sun broke at their backs, the Union forces drove the Confederates from the field. His men, said Ramseur ruefully, “did some tall running.”

While the Union troopers drove the Tarheels, Wright funneled the VI Corps into the canyon, but by 7 o‘clock Sheridan’s timetable was already a tangle of wagons, cannons, and wounded men. The inevitable traffic jam prevented the timely passage and deployment of Emory’s XIX Corps. A soldier in the XIX Corps left a vivid description of the confusion: “The scene in this swarming gorge was one not easily forgotten. The road was crowded with wagons, ambulances, gun carriages, and caissons, getting onward as fast as possible, but so slowly that one might already divine that we should fight our battle without artillery. On the left and on the right endless lines of infantry struggled through underbrush, and stumbled over rocks and gulleys. Presently, we met litters loaded with pallid sufferers, and passed a hospital tent where I saw surgeons bending over a table, and beneath it amputated limbs lying in pools of blood.”

While Sheridan cursed the “stupid clutter” and fumed at losing the upper hand, Early made good use of the respite given him by the fortunes of war. He moved quickly to repair potential damage, redirecting Gordon and Rodes to join Brig. Gen. Gabriel Wharton at Stephenson’s Depot, the northernmost gateway to Winchester. By 10:30 am, the newly arrived force had extended Ramseur’s short defensive line along a wooded plateau east of Winchester.

“The Fiercest Battle Fought by Grant”

By that time, Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge dispatched Wharton’s division to support Confederate cavalry contesting crossings by Merritt’s cavalry division five miles north at Seiver’s and Locke’s Fords. Curiously, once the crossings had been secured, the Union advance ground to a halt. Neither Merritt nor Torbert, who accompanied the division, acted with any sense of urgency, and from daylight until after 10 am the Federal forces basically stayed put. Torbert attributed the delay to the strength of the Confederate battle line and to the cavalry’s need to occupy Breckinridge’s attention to prevent the Kentuckian from shifting his division to Winchester, or “at least, if he did send it, to follow closely in his rear and get on the enemy’s flank.”

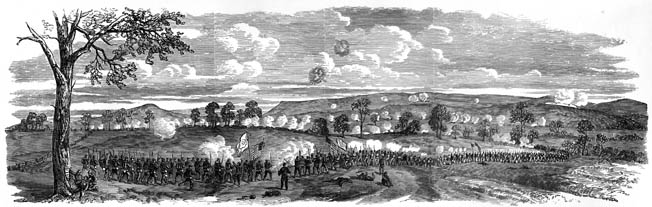

Meanwhile, XIX Corps had struggled through the traffic jam and deployed north of the Berryville Pike in a lot known as the First Woods. As the infantry deployed, Confederate batteries opened up, and Union batteries were quick to respond. “Their artillery seemed to be without limit,” remarked one Confederate, “so constant and fierce was their fire.” The intensity of the artillery duel slackened when, at 11:40 am, Sheridan launched a three-division assault into an open field 600 yards wide, known as the Middle Field. Early had profited from the long delay, and his seasoned veterans waited in another belt of woods, known as the Second Woods. They reacted immediately and vigorously, pouring heavy fire into the blue ranks, and Confederate horse artillery played havoc on the flanks.

As the VI Corps advanced on the Union left, the XIX Corps division of Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover reached the Second Woods and hit Gordon’s division with telling effect. “The roar of battle,” said a Union officer, “pealed up from that woods; and smoke and flame streamed out in a long line, as though the whole forest had been suddenly ignited. The conflict was as fierce as the fiercest battle fought by Grant, from the Rapidan to Petersburg.” The Union troops, in desperate hand-to-hand fighting, broke through and drove back the Georgians some 300 yards. But the impetuous attack quickly lost cohesion and was brought to a halt when seven Confederate cannons, parked hub to hub, blasted sheets of canister point-blank into the attackers. On the left, the weighty combination of two VI Corps divisions fell heavily on the embattled Ramseur and collapsed his left flank, sending the Confederates streaming back toward Winchester.

“My God! This is a Perfect Slaughterhouse!”

As the VI and XIX Corps advanced, a dangerous gap developed, exposing them to being torn asunder. Unknown to Sheridan, the Berryville Pike, which was the army’s guidepost, turned slightly to the south and created a gaping hole in the Union line at the junction of the two corps. Between 12:30 and 1:30 pm, Gordon and Rodes launched swift and powerful counterattacks into the disjointed Union commands. The sledgehammer blows succeeded in driving the confused Federals out of the Second Woods and back across Middle Field. The musketry became so intense that a Union brigadier saw his flanks seem to melt away. The retreat threatened to become a rout.

Attempting to rally his men, Emory exclaimed: “My God! This is a perfect slaughterhouse!” Confederate horse artillery worked deadly execution among the panic-stricken fugitives. The Union line bent and buckled. As the Federals turned and ran, the Southerners “raised one of the awfulest yells that ever met my ears,” an Iowa soldier later recalled. The butternuts pressed on, determined to finish the job, and they might have done so but for the reserve divisions of the VI and XIX Corps moving up to check the attack.

Brigadier General William Dwight of the XIX Corps advanced his men into the “basin of hell” to stem the tide but did not advance 200 yards into the Second Woods before being pinned down by murderous fire. “The veterans of Stonewall Jackson fired amazingly low,” a member of the 114th New York recalled admiringly, “so that the grass and earth in front of the regiment was cut and torn up by a perfect sheet of lead.” Farther to the left, the Confederates drove relentlessly forward. “They aimed better than our men,” a Union officer admitted. “They covered themselves more carefully and effectively; they could move in a swarm, without much care for alignment and touch of elbows. In short, they fought like redskins, or like hunters.”

The reserve division of the VI Corps, under Brig. Gen. David Russell, advancing obliquely across the enemy front, caught, stunned, and blunted the Confederate thrust. The climactic moment arrived when his third brigade, led by Brig. Gen. Emory Upton, mounted a bayonet charge. Captain Henry DuPont observed, “Upton’s military instincts showed him what ought to be done, and he took responsibility of doing it.” Another observer wrote, “The charge of this brigade was the finest spectacle in the infantry battle of the day.” Wright called it “the turning point of the conflict.” By 2 pm, hostilities sputtered out from sheer exhaustion, and both sides settled into fitful firing.

Over 3,000 Casualties at the Middle Field

The engagement at the Middle Field was one of the bloodiest of the entire war, witnessing more than 3,000 causalities, including Generals Rodes and Russell, each of whom was killed instantly by exploding shells. The XIX Corps alone took 40 percent casualties, including every regimental commander. The Confederates had wrecked one Union corps and held the other to a standstill, but Gordon’s near-success marked the high point of Southern fortunes for the day.

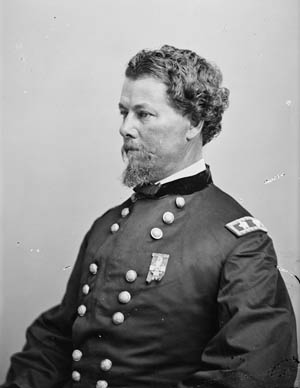

All in all, it had not been a good day for Sheridan, but his error-plagued offensive might yet be salvaged by his reserve. At 1 pm, he turned to his good friend and fellow Ohioan George Crook and directed him to move the VIII Corps from Opequon Creek into position on the right rear of the XIX Corps. DuPont, who was with Crook and Sheridan at the army observation post, quoted the commanding general as saying, “Crook, put in your corps to support Emory, and look well for the right flank.” The phraseology of the order would later create a dispute about the role Sheridan had planned for the VIII Corps and who was the actual architect of the culminating flank attack that put Early’s army to rout.

In his memoirs, Sheridan maintained that he directed Crook “to push his command forward as a turning column in conjunction with Emory.” Conversely, Crook asserted in his memoirs, “As so far as I know the idea of turning the enemy’s flank never occurred to him, but I took the responsibility on my shoulders.” DuPont supported Crook’s version of events and criticized Sheridan for keeping Crook so far removed from the battlefield, thus preventing VIII Corps from exploiting a breakthrough or moving quickly beyond the Confederate lines. It seems likely that Sheridan had no definite plan in mind for Crook. Like so many other things for Union forces that day at Winchester, grand designs had a way of becoming undone in the heat of combat.

Sheridan’s Knockout Blow

The controversy lay in the future; for the moment, the two small divisions, dubbed the “Mountain Creepers” or the “Buzzards,” moved to attack on both sides of Red Bud Run, a deep, marshy slough north of Winchester. Colonel Joseph Thoburn drove west on the south bank of the Red Bud into the First Woods, while Crook personally led Colonel Isaac Duval’s division farther to the right with the intention of feeling his way around the Confederate left. Meanwhile, to the north Federal horsemen were hammering Confederate cavalry and Wharton’s division into a rapidly contracting line on the outskirts of Winchester. By 3 pm, Sheridan was poised to deliver a knockout blow.

The renewed Union advance occurred, east and north, all along the line. Crook’s flanking maneuver was beautifully executed, and DuPont’s artillery ripped into Gordon’s flank. Duval’s advance was made at virtually a right angle to the main attack, overlapping the Confederate line. In the charge, Duval was seriously wounded, and future President Rutherford B. Hayes assumed command of the division. The Federal attackers were greeted by a galling fire of muskets and artillery as they crossed the marshy flood plain beyond Red Bud Run. “To stop was death,” Hayes wrote to his wife, Lucy, two days later. “To go on was probably the same, but on we started again, the rear and front lines, and different regiments of the same line mingled together, and reached the rebel side of the creek with lines and organization broken, but all seemed inspired by the right spirit, and charged the rebel works pell-mell in the most determined manner.”

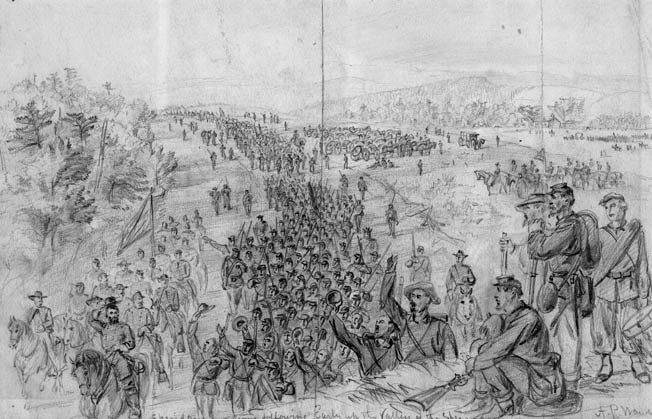

Thoburn’s division emerged from the First Woods and attacked across 600 yards of open field. The butternut ranks burst open like a blast furnace. Caught in the jaws of the rapidly closing Union vise, Gordon was forced to abandon the Second Woods, punishing his pursuers as he withdrew. “Press them, General, I know they’ll run,” Sheridan exhorted Brig. Gen. George Getty, one of his division commanders. By 5 pm, as the infantry fight reached a crescendo, five brigades of Union cavalry pounded in from the Valley Pike, overrunning a desperate resistance at Collier Redoubt and Star Fort. Said one New York cavalryman: “Every man’s saber was waving above his head, and with a savage yell, we swept down upon the trembling wretches like a besom of destruction.” Another trooper was more succinct, calling the charge “a carnival of death.”

Defeat turned into rout, and rout became panic as the Confederates were sent “whirling through Winchester,” in Sheridan’s memorable phrase. The battle had been the largest and most desperately fought contest in the Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan’s forces, committed to the offensive, lost a total of 5,020 casualties, or approximately 12 percent of their men. Although the Northerners suffered over twice as many casualties as the Confederates, the combat prowess of the Army of the Valley had been badly crippled. Early had incurred 3,610 casualties, nearly 30 percent of his command—roughly comparable to Lee’s losses at Gettysburg. One of the last Confederate casualties was Colonel George S. Patton of the 2nd Virginia Regiment, who fell to a sniper’s bullet while attempting to rally his men in the jumbled alleys of Winchester. His grandson, also named George S. Patton, would gain fame in World War II.

“Hurrah For This Loyal Girl!”

Sheridan, accompanied by Crook, rode through Winchester’s littered streets at sundown. Looking for a quiet place to send a victory telegram to Grant, Sheridan went to the home of Rebecca Wright, the Quaker schoolmarm who had sent him such valuable information a few days earlier. “Hurrah for this loyal girl!” Sheridan cried, shaking her hand. His men had performed superbly, Sheridan informed Grant. “They charged and carried every position taken up by the Rebels from the Opequon Creek to Winchester. We are after them tomorrow. This army behaved splendidly.”

So had Sheridan. His instinctual ability to sense the ebb and flow of an engagement and adapt to the fluid conditions on the battlefield were on full display at Winchester. “In one respect Sheridan was especially remarkable,” recalled a staff officer, “that was in watching the troops in battle, seeing for himself what was done and taking instant advantage of the chances that offered.” His conduct of the battle reflected his personality—aggressive, headstrong, and relentless. There had been flaws in his tactical scheme and conduct of the battle, but he could overcome his mistakes because of his three-to-one numerical superiority. “Sheridan’s strength was Early’s weakness,” wrote Confederate cavalryman Thomas T. Munford. A Virginia private concurred. “We were so outnumbered that we could not prevent from being flanked by the enemy,” he said. A Union cavalryman aptly attributed the Northern victory to “those living lines of men like the foaming waves of ocean.” At Winchester, the blue waves had crashed and broken over the gray lines. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments