By Joshua Shepherd

By mid-afternoon on September 20, 1944, the deceptively placid waters of Holland’s Waal River were wreathed in dense clouds of smoke. Allied tanks and artillery had bombarded the north bank of the river for half an hour, unleashing a deafening barrage intended to soften up German defenses. The artillery crews had fired hundreds of rounds of high-explosive and smoke shells. These preparations were necessary to protect the 260 men of the 82nd Airborne Division who were crouched down behind a dike on the south bank of the river. The airborne troopers would shortly begin one of the most desperate operations of World War II.

When the artillery ceased fire, plans called for the paratroopers to rush for the riverbank, grab collapsible canvas boats, and paddle across 400 yards of open water into the teeth of enemy fire. Major Julian Cook, who would command the first wave of the attack, had a sinking feeling in his gut that he was leading his men into a bloody disaster. “Somebody has come up with a real nightmare,” the battalion commander thought to himself.

Subsequent to the D-Day landings in Normandy more than three months earlier, Allied troops had faced a brutal fight in expanding their toehold in northwestern France. For a grueling period that lasted six weeks, unexpectedly stiff resistance by German troops fighting on the defensive in the bocage country of Normandy had resulted in heavy casualties. The Allies paid dearly in blood for every yard of ground they gained. But by the third week of July, the tide had begun to turn.

British troops attempted to break through German positions east of Caen on July 18. The Germans repulsed the attack but weakened their line farther west as they stripped it of troops to reinforce their positions opposite the British. On July 25 the U.S. Twelfth Army Group smashed through German defenses west of St. Lo, producing the long-awaited breakout from Normandy. Lt. Gen. George Patton sent armored columns through the gap. British troops expanded the scope of the attacks. By the beginning of August, the war in France tipped decidedly in favor of the Allies.

As the German war machine struggled to stem outright collapse, Allied superiority in men and matériel began to tell. In a crushing sweep through the German left, the Americans moved south through open country and then turned east, intending to link up with British and Canadian forces pushing south from Caen. Allied commanders hoped to trap the elite armored units of Germany’s Army Group B in a pocket south of Falaise.

Furious fighting during the middle of August tightened the noose. As the German 7th and 15th Armies frantically scrambled to escape the killing ground of the Falaise Pocket, the Allies subjected them to a battering by heavy artillery and ground attack aircraft. By August 21, their escape route was entirely cut off. Germany’s Army Group B had been decimated. The Germans suffered 10,000 dead, 20,000 wounded, and 50,000 troops captured. The Allies were elated. “Two and one half months of bitter fighting have brought the end of the war in Europe in sight, almost within reach,” Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower wrote in his intelligence summary for August.

As disorganized German columns streamed eastward, Allied commanders were anxious to maintain momentum and keep the enemy on the run. But the sudden battlefield success proved to be a logistical double-edged sword. As armored columns thundered toward the frontiers of Germany, they outstripped their lines of communication and faced a crippling lack of fuel. The armies consumed a staggering one million gallons of fuel per day, every drop of which had to be transported from the French coast. It was a painful dilemma for frustrated field commanders. Although the German Wehrmacht forces in France were clearly demoralized and ripe for a fatal blow, fuel shortages ensured that the Allies could not fully exploit the opportunity. Despite the astonishing successes of August 1944, the Allied juggernaut slowed to a creeping advance.

Recently promoted Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery vowed to break the stalemate. Widely regarded as capable and considered a darling of the British public, he was also vain, contentious, and quarrelsome. But to his credit Montgomery also was an innovative strategist who was willing to entertain bold ideas. With the fighting bogged down in eastern France, it seemed the war might linger into yet another year. Montgomery began sketching out plans in September for a daring campaign. The Allies christened their bold offensive Operation Market Garden.

Montgomery developed a novel approach to a vexing situation. In a September 10 meeting with Eisenhower, the British field marshal laid out his proposal. Rather than directly confront the substantial barrier of the Rhine River, as well as enemy defensive positions on the German border known as the Siegfried Line, Montgomery hoped to entirely bypass the defensive works. His plan called for armored units of Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks’ XXX Corps of Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army to make a deep strike into Holland, which would outflank the Siegfried Line in a massive turning movement. Once the Allies were firmly established in Holland, they would be in a position to drive directly southeast into the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland. If successful, there was a chance that the operation would unhinge German positions throughout Western Europe. If everything went according to plan, the war might be over by Christmas.

To pull it off, Montgomery planned to bolster the armored thrust by dropping three divisions of airborne troops deep behind enemy lines. The paratroopers’ primary objective would be the seizure of bridges that were crucial to XXX Corps’ advance into Holland. The Allies had a formidable airborne force at their disposal, which was Lt. Gen. Lewis Brereton’s newly created 1st Allied Airborne Army. Eisenhower had held the airborne army in reserve for just such an operation.

To facilitate the armored advance, the Allies would need to funnel precious supplies of fuel and matériel to the forces participating in Market Garden at the expense of American forces farther south. Much to the annoyance of American generals such as the Third Army’s Patton, Eisenhower approved the plan. For his part, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley was not terribly impressed by the entire scheme. Although he thought the plan was inspired, Bradley foresaw trouble. “It’s a foolhardy thing to do, and you’ll take a lot of casualties,” Bradley warned Ike.

Bradley’s assessment proved prescient. A number of demoralized German units in Holland had nearly disintegrated due to combat losses and desertion. The Allies believed this left the Netherlands open for the taking. But the Germans had rushed in reinforcements in an effort to stabilize their northern flank. The reinforcements included Generaloberst Kurt Student’s crack 1st Parachute Army, which took over the front along the Belgian border. Worse still, Allied reconnaissance flights and reports from the Dutch Resistance warned of the presence of substantial German armored columns in the vicinity of Arnhem. In the rush to implement Market Garden, top Allied commanders conveniently ignored the intelligence. When warned that German armor might be near the drop zones, Montgomery brushed off the threat. “He ridiculed the idea [and] felt that the greatest opposition would come more from terrain difficulties than from the Germans,” wrote Maj. Gen. Bedell Smith, the chief of staff of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.

As outlined by Montgomery in his briefing to Eisenhower, the airborne army would “capture and hold the crossings over the canals and rivers on the Second Army’s main axis of advance” from Eindhoven to Arnhem. Monty described to Ike an “airborne carpet” in which thousands of paratroopers would be dropped around the key bridges with orders to ensure that they remained intact.

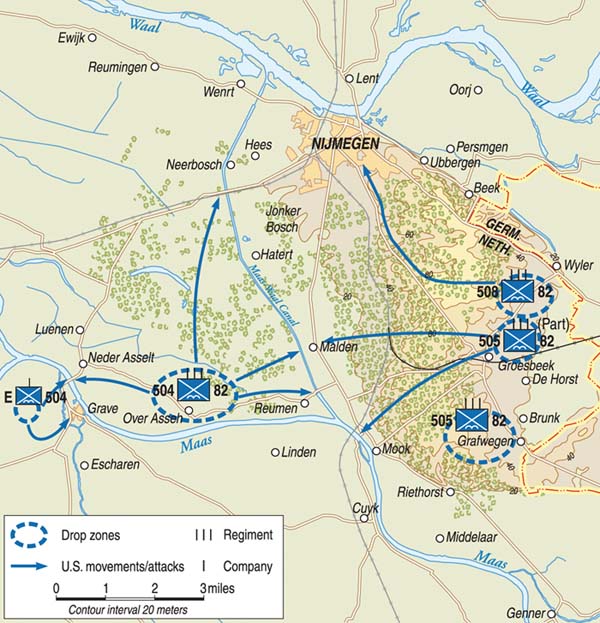

The first objective, Eindhoven, was assigned to the Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s U.S. 101st Airborne Division. A total of nine road and rail bridges were situated in 101st’s sector. Specifically, Taylor’s division was tasked with seizing multiple bridges at Eindhoven, the bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal at Son, and the bridge over the Willems Canal near Veghel. The second objective 20 miles to the north was Nijmegen. Brig. Gen. James Gavin’s 7,300-strong U.S. 82nd Airborne Division had orders to secure the bridges over the Maas River at Grave and the Waal River at Nijmegen. Altogether, Gavin’s area included 11 key bridges.

The third objective, Arnhem, was assigned to Maj. Gen. Roy Urquhart’s British 1st Airborne Division. The British paratroopers had orders to secure the town’s strategically important bridge over the lower Rhine River. Operational command of the paratroopers fell to Lt. Gen. Frederick Browning, who was not only the commander of the British 1st Airborne Corps but also deputy commander of the 1st Allied Airborne Army. Browning would accompany Gavin’s division in its air drop on Nijmegen. As soon as fair weather permitted, Market Garden would proceed as planned.

The geographic obstacles of Market Garden were incredibly challenging. Horrocks’ corps would have to cross five rivers, three major canals, and multiple streams and ditches. Worse still, the armored column would be forced to use a single narrow highway that angled toward Arnhem. The British tanks and armored vehicles would have to stay on the elevated highway because the marshy lowlands of Holland were impossible for armor to negotiate.

The 82nd Airborne Division had a pivotal role to play in Market Garden. The division had a storied history dating back to World War I when, as the 82nd Division, it saw heavy fighting on the Western Front. Before the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. Army High Command, which saw the need for an elite parachute force, redesignated the unit as the 82nd Airborne Division.

After receiving a crash course in the nascent art of airborne operations, the U.S. Army deployed the 82nd Airborne to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, where it quickly proved itself in combat drops in Sicily and mainland Italy. The commander of the 82nd Airborne at the time was Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway. During the planning for Operation Overlord, Ridgeway had successfully convinced Eisenhower to increase the strength of the two American airborne divisions from two parachute regiments and a single glider regiment of two battalions to three parachute regiments and a glider regiment of three battalions.

The 82nd Airborne also performed ably in Operation Overlord in Normandy where it incurred heavy casualties in more than a month of hard fighting. When Ridgway was promoted to command the XVIII Airborne Corps, he enthusiastically recommended New York native Gavin, a rising star known for his tenacity and for leading by personal example, to succeed him.

At the outbreak of World War II, Gavin was a company commander in the Army’s airborne arm. He served with distinction in the airdrops in Sicily and Normandy. When he was briefed on the 82nd Airborne’s role in the operation, Gavin was incredulous. His troops would have to capture, at a minimum, the three major bridges in his sector. Moreover, it was imperative that the division maintain control of Groesbeek Heights, a five-mile-long ridgeline southeast of Nijmegen. Although only 300 feet high, the ridge loomed over the Maas and Waal Rivers. What is more, the ridgeline controlled the approaches from the German border.

Gavin’s three parachute regiments were Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), Colonel William Eckerman’s 505th PIR, and Colonel Roy Lindquist’s 508th PIR.

Gavin’s greatest concern was selection of drop zones. British planners had opted for landing fields up to six miles away from the targeted bridges. Although Gavin was inclined to risk heavier casualties by dropping closer to the objectives, he kept his reservations to himself. “I assumed that the British, with their extensive combat experience, knew exactly what they were doing,” he wrote.

The morning of September 17 dawned bright and clear. At 10:25 am transport aircraft carrying the men of the 82nd Airborne began taking off from airfields in Lincolnshire. The aerial armada included C-47 tow planes, troop transports, and American-built Waco and British-built Horsa gliders. The armada ferrying Gavin’s troopers consisted of 482 planes and 50 gliders.

Despite the seemingly invulnerable display of Allied military might, the men were in for a nerve-racking 30-minute flight across the North Sea to the drop zones in Holland. With nearly 5,000 aircraft aloft, accidents were inevitable. As the armada neared the coast of Holland, German antiaircraft guns began pounding away at the vulnerable aircraft flying low at 1,500 feet.

As the planes carrying the 82nd Airborne neared Nijmegen, the threat from German antiaircraft fire slackened. Allied bombers and fighters had attacked enemy positions around the city for nearly three hours preceding the arrival of the troop transports, thereby wreaking havoc on German defenses. Only a single antiaircraft gun in Nijmegen remained operable.

At 12:45 pm American Pathfinders began parachuting in the vicinity of Nijmegen. Their job was to mark drop zones for the pilots. Gavin’s first wave of paratroopers followed close on their heels. The initial drops were made by the 505th and 508th PIRs. Gavin jumped with the 505th, which was his former unit.

It was a harrowing daylight descent for the paratroopers, who made easy targets for Germans on the ground. Falling near Groesbeek Heights, Captain Briand Beaudin, the surgeon of the 3rd Battalion of the 508th, was alarmed to see he was about to land on an enemy antiaircraft position. Determined to afford himself a fighting chance, Beaudin drew his .45 sidearm and opened fire. “[I realized] how futile it was, aiming my little pea-shooter … in the air above large-caliber guns,” he wrote. After landing safely, Beaudin succeeded in capturing the stupefied German gun crew.

Other German crews put up more of a fight, downing three American fighter planes and firing at descending paratroopers. Private Edwin Raub of the 505th, who came under 20mm antiaircraft fire, side-slipped in order to land near the gun emplacement. Still attached to his chute, Raub rushed at the gun crew, firing bursts from his Thompson submachine gun. He killed one member of the gun crew and captured the rest.

More Pathfinders fanned out to mark the landing zones for the artillery and the 82nd’s glider-borne forces. The overall casualties in the initial drop were negligible. In just 18 minutes, Gavin had 4,500 men on Groesbeek Heights. Gavin, though, fractured two of his vertebrae in the drop; despite the pain, the plucky commander went about his duty.

Farther to the west, the 504th was making its drop near the village of Grave. The 2nd Battalion’s E Company had orders to seize the bridge over the Maas River, the southernmost bridge in the 82nd’s sector. As the aircraft transporting Lieutenant John Thompson, a platoon leader in E Company, approached its assigned drop zone and the jump light flashed green, he looked out of the aircraft only to see it was over buildings. He waited a few seconds, and when it was over farm fields, he ordered his men out of the airplane. After he assembled 16 of his men on the ground, Thompson noticed the bridge over the Maas was only 300 yards away. Even though he and his men were isolated from the rest of the company, he led them toward the bridge.

Wading through drainage ditches in water up to their armpits, the paratroopers were able to get in close proximity to the nine-arch bridge span despite the presence of enemy troops around it. When Thompson saw the Germans at the south end of the bridge scurrying around a power plant, he ordered his men to rake the area with machine-gun fire. In a few minutes two trucks loaded with German reinforcements arrived. A paratrooper shot the driver of the lead truck. Using whatever cover he could find, Thompson continued to work his way toward the bridge. As he did so, he spotted a 20mm cannon mounted in a concrete flak tower.

The paratroopers made short work of the enemy positions, which were manned by rear-echelon German troops. One of Thompson’s men eased his way forward and fired two rounds from a bazooka into the top of the flak tower. When the Americans stormed the tower, they found two dead Germans and one who was wounded.

Thompson continued to press his attack. He ordered his men to fire the captured 20mm gun at German targets on the north bank. His squad’s tenacious fighting had paid off handsomely. Reinforcements soon arrived to ensure that the Maas Bridge would remain in American hands.

North of the Maas, elements of the 504th struggled to secure a bridge over the Maas-Waal Canal. The Germans had blown a bridge at Malden when they saw the Americans approaching. A German pillbox, which bristled with machine guns, situated on an island in the canal defended a bridge at Heuman.

German machine-gun fire kept the American at bay for much of the day. Nevertheless, the paratroopers maintained pressure on the Germans. The paratroopers set up a machine gun on the bank of the canal to furnish covering fire. As the two sides traded machine-gun fire, four paratroopers made a successful dash across the bridge, while seven others crossed the canal by boat farther downstream.

To the amazement of the Americans, the Germans failed to destroy the bridge. But the Americans’ grip on the position remained tenuous until the sun set. Under cover of darkness, an American squad sprinted across the bridge and severed the German demolition lines. The paratroopers also assaulted and captured the German pillbox in the canal. The paratroopers succeeded just before midnight in seizing two of the three bridges assigned to them.

That day German senior officers stationed near Arnhem became embroiled in a heated disagreement. Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Bittrich, commander of the II SS Panzer Corps, and his subordinate, Brigadeführer Heinz Harmel of the 10th SS Panzer Division, argued for the immediate demolition of the bridge at Nijmegen; however, Field Marshall Walther Model, commander of Army Group B, overruled them. Model said that under no circumstance was the bridge to be destroyed. He hoped to preserve the bridge for a counterattack he was planning.

Outside the 82nd area of operations, Market Garden was going horribly awry. Horrocks’ XXX Corps, which encountered stiff resistance from the Germans as it advanced from the Belgian border, had fallen far behind schedule. Taylor’s 101st Airborne at Eindhoven was struggling to keep the road open for British armor.

Meanwhile, the British 1st Airborne at Arnhem faced nothing short of a nightmare. Although warnings about German tanks had gone unheeded, the British paratroopers had dropped in the midst of some of the toughest troops the Germans had in the field. A single British battalion secured a tenuous grip on the bridge at Arnhem. The rest of the division, in a fight for its life, was isolated on the outskirts of the city.

At the time of the airdrops, Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps was refitting north and east Arnhem. The corps comprised Obersturmbannführer Walter Harzer 9th Panzer Division and Harmel’s 10th SS Panzer Division. Both divisions had fought in Normandy, and they had barely escaped total annihilation in the Falaise Pocket.

Seizing the bridge at Nijmegen would consequently prove imperative to relieving the British in Arnhem, a task nonetheless complicated by the uncertainty of the situation experienced by participants in combat known as the fog of war. Gavin expected a battalion of the 505th to make an attempt on the bridge as soon as possible after the regiment landed. By Gavin’s recollection, he further advised Lindquist, the 508th commander, to approach Nijmegen from the pastures to the east, thereby bypassing much of the city. Lindquist, who had a different recollection, intended to make an attempt to capture the Nijmegen Bridge only after he had completely secured his position on the northern Groesbeek Heights. When no assault on the bridge materialized by evening, an alarmed Gavin ordered Lindquist to make an immediate push for the bridge.

Unfortunately, the attack would unfold in precisely the manner that Gavin hoped to avoid. Lindquist’s 1st Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Shields Warren, had been assigned a holding position southeast of Nijmegen before receiving orders to move for the bridge. Unaware of Gavin’s preferences for the assault, Warren pushed directly into Nijmegen from the south.

As Warren’s troopers groped their way toward the bridge, fighting erupted in the streets of Nijmegen. In the worst sort of bad luck, the Americans had bumped into elements of the II SS Panzer Corps that had been rushed south from the Arnhem area. The crack SS troops bolstered German defenses at two traffic circles that controlled the approaches to the rail and road bridges over the Waal.

In the confused night fighting, it was difficult to tell friend from foe, and savage close-quarters combat ensued. In an attempt to maintain the element of surprise, some of the Americans had been ordered not to fire their weapons. Corporal James Blue of the 508th, who abruptly came face to face with an SS officer, attacked the German with his trench knife, but found the blade too short to do the job, so Blue killed the German with a spray of bullets from his Thompson submachine gun.

Facing a gauntlet of German machine-gun fire, the ill-coordinated American attack was making little headway. “Bullets were whistling down the street, and there was so much confusion in the darkness that the men did not know where the others were … we couldn’t make it to the bridge,” wrote Private James Allardyce of the 508th. With no other choice at the time, Warren called in his men and consolidated a secure position. The initial attempt on the Waal Bridge, conducted in improvised haste, had been stopped cold.

Early the following day, Gavin was faced with a grave threat to his thinly occupied position on Groesbeek Heights. Across the German border to the east of the Americans, a scratch force of German rear-echelon troops had hastily formed to contest the landings. The troops were under the overall command of General der Kavalerie Kurt Feldt, who initially had little more than headquarters staff under his command. To make up for such manpower shortages, Feldt cobbled together a polyglot force out of any men he could get his hands on, including trainees, convalescents, reservists, and the students of a Luftwaffe noncommissioned officer school. Promised that he would be reinforced by two divisions of crack fallschirmjagers, Feldt was under orders to wage a desperate delaying action by aggressively attacking the enemy drop zones.

By the morning of September 18, Feldt had assembled 3,400 inexperienced infantrymen into the 406th Landesschuetzen Division of Korps Feldt. The force had five armored cars, three half-tracks, and various captured Russian howitzers. Feldt entertained little hope that his rag-tag collection of green troops could defeat veteran American paratroopers. “I had no confidence in this attack with its motley crowd,” wrote Feldt. “But it was necessary to risk the attack.”

At 6:30 am on September 18, Feldt hurled his force at Groesbeek Heights. The Americans, who had faced little resistance in that sector, were initially caught off guard. “To our surprise, at the beginning, the attack made slow progress everywhere,” Feldt wrote. His men managed to gain ground against the Americans, and they fought their way into the village of Mook.

Not surprisingly, the German assault stalled as the more experienced American paratroopers collected themselves. A German staff officer of the 406th Division rushed forward to take over a battalion that had been pinned down. The troops were old men who were veterans of World War I. They had just been called up to fill the depleted ranks of the Wehrmacht. The staff officer rallied them for another assault. “Can’t you see that it’s up to us … to run the whole show again?” he asked them.

Although the German attack briefly pressed forward, the momentum soon shifted in favor of the Americans. Gavin shuffled around what troops he had to shore up his lines and recalled Warren’s battalion from Nijmegen. Although the Germans began to take the worst of the fight, the Americans paid grudging respect to their tenacity. “They were all around us and determined to rush us off our zones,” wrote Arthur “Dutch” Schultz, a BAR gunner with C Company, 505th. A furious American counterattack down the eastern slopes of Groesbeek Heights began driving the enemy back toward the German border.

Just then another wave of American planes arrived over Groesbeek Heights as the battle raged on the ground. As German troops scrambled for cover, Allied fire from the newly arrived aircraft tore into their ranks. “Their crew machine guns swept the entire field with fire,” wrote the staff officer of the 406th Division. “Bombs exploded in between, [and] it was as though all hell had broken loose.” With German infantry on the run, American gliders began landing on the drop zones. Exploiting the chaos, elements of the 505th launched a counterattack across the northern drop zone. The men of the 406th Division panicked when gliders landed nearby. During their mad dash for the rear, Feldt narrowly avoided capture.

Despite the successful arrival of Allied reinforcements and supplies, Browning was growing anxious regarding developments. Although information from Arnhem was sketchy at best, it was readily apparent that the British 1st Airborne Division was cut off and facing a tough fight of its own. Without reinforcement from XXX Corps, which would have to pass over the bridge at Nijmegen, the British troopers at Arnhem would be destroyed in detail. On the afternoon of September 18, Browning informed Gavin that something had to be done. “Nijmegen bridge must be taken today [or] at the latest tomorrow,” said Browning.

By that time the lead elements of XXX Corps, the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, linked up with the 82nd Airborne. With the assistance of the British tanks, Gavin planned yet another attack on the Nijmegen road bridge for the afternoon of September 19. To lead the infantry element, Gavin chose Lt. Col. Ben Vendevooort, the hard-fighting commander of the 2nd Battalion, 505th. The objective was to dislodge the Germans from the opposite bank of the Waal.

Such expectations were sorely misplaced. By that point, German defenses on the south bank of the Waal were manned by a battalion of crack troops from the 22nd Panzergrenadier Regiment, many of them veterans of the Eastern Front, under the command of the resourceful Captain Karl-Heinz Euling. When the attack proceeded, Vandervoort’s paratroopers followed 40 British tanks and armored vehicles into Nijmegen. One column moved for the railroad bridge, while another angled toward the road bridge. All went well until the Allies neared the bridges. American troops scattered for cover when German snipers opened fire, and German guns began knocking out the lead British vehicles. Fierce fighting continued until nightfall, but the German defenses south of the Waal River had again proven impervious to direct assault.

With the outcome of Operation Market Garden in the balance, Gavin settled on the most desperate of measures. At a meeting of senior officers that evening, which included Browning and the recently arrived Horrocks, he outlined what he had in mind. Repeated direct assaults against the Nijmegen Bridge had proved both futile and costly, he explained, and the beleaguered British paratroopers in Arnhem could wait no longer.

Gavin proposed taking the bridge from both ends simultaneously. While another direct attack, spearheaded by the tanks of the Grenadier Guards, moved against the southern approaches, an assault party of American paratroopers would cross the Waal River by boat and seize the northern end of the bridge. It was an audacious plan but, by Gavin’s reasoning, there was little choice. “The attempt has to be made if Market Garden is to succeed,” said Gavin. Browning, quickly running out of options, gave his approval.

The unenviable assignment of the river crossing fell to Tucker’s 504th. A taciturn veteran of the Anzio landings, the cigar-chomping Tucker said little during the briefing. But clearly alarmed by the price his men would pay to seize the road bridge, he wanted direct assurances of support from his British counterparts. Captain T. Moffatt Burriss of the 504th wrote that Horrocks’ confidence was effusive. “My tanks will be lined up in full force” for the push to Arnhem, and “nothing will stop them,” said Horrocks.

The attack was scheduled for 3 pm on September 20. A mile downstream of the railroad bridge, the 504th’s 3rd Battalion, commanded by Major Julian Cook, waited nervously behind a dike on the south bank. Few entertained any illusions about the deadly nature of their assignment. Cook was dismayed by the entire plan, but he was determined to carry out his orders.

Thirty minutes before the assault was scheduled to take place, Allied aircraft, artillery, and tanks opened up a deafening bombardment in an effort to soften up German defenses on the north bank. It was an impressive spectacle, but officers peering through binoculars had no idea if the fire was having much of an influence on the Germans.

While the artillery banged away, the assault boats, on loan from the British, finally arrived. They were rather unimpressive, foldout contraptions with plywood bottoms and canvas sides. Many of the craft had only two paddles whereas they were supposed to have eight. Nevertheless, the paratroopers proceeded with the crossing. They hurriedly assembled the boats. Each boat would carry a complement of 13 paratroopers and three engineers. The men had little time to spare. When the artillery barrage ended, a thick smokescreen drifted across the river, and an officer shouted “Go!”

Gripping the gunwales and racing for the river’s edge, the Americans were quickly afloat but ran into trouble from the outset. Desperate to cross the river as quickly as possible, men began frantically paddling with their rifle butts. The swift river current spun many of the ungainly boats in circles. Worse yet, strong winds soon dispersed the smokescreen. Drifting in the middle of the Waal River, Cook’s paratroopers were exposed to the full fury of the enemy fire.

Germans on the north bank opened up with machine-gun and 20mm cannon fire, shredding canvas boats and the helpless paratroopers they contained. Dozens fell overboard or collapsed on the bloody floor of the boats. The river was rent by a nightmarish cacophony of shellfire, curses, and shouts of terror. In the midst of it all, Cook did his duty to the cadence of the rosary. “Hail Mary, full of grace,” he repeated to himself as he paddled.

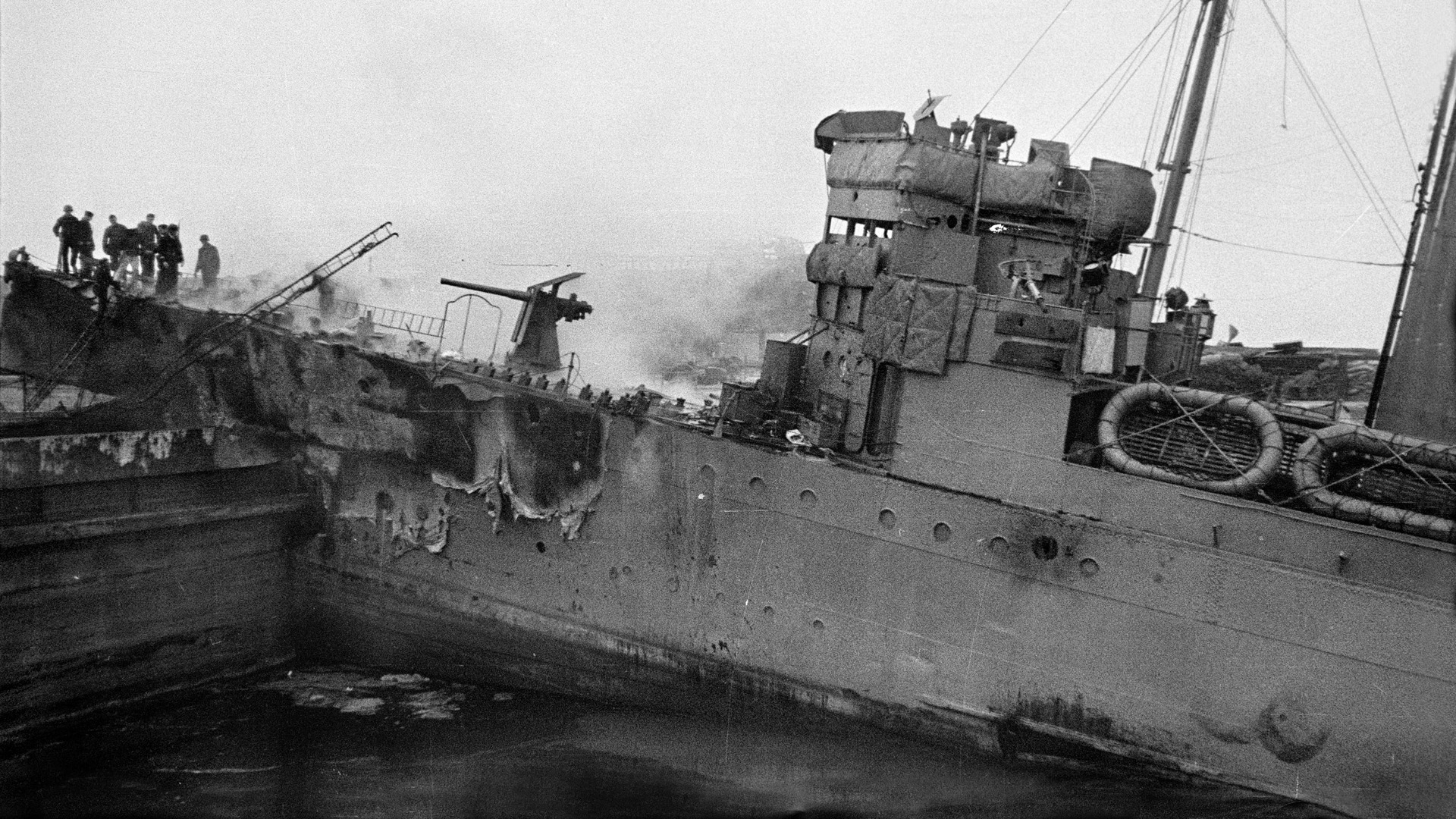

Despite such bravery, the men of Cook’s battalion endured the brutal gauntlet. Captain Burriss of I Company likened the unrelenting German fire to a hailstorm. When one of his engineers was struck in the wrist, Burriss reached for the rudder when the soldier was struck by a 20mm round. The captain would never forget it. “It just blew his head apart,” he wrote. In the face of such horror, survivors continued paddling to shore. Only half of the 26 boats reached the north bank. When they did, furious American paratroopers jumped out and raced toward the dike.

Settling a bloody score was first on their minds. The men were “rendered crazy by rage and lust for killing,” wrote Captain Henry Keep of the 504th. The Americans made short work of the German defenders, who turned out to be inexperienced rear-echelon troops. Enemy positions behind the dike collapsed in the face of the American steamroller. When the paratroopers reached the northern end of the rail bridge, German troops in Nijmegen were attempting a retreat to the north bank. The Americans, turning on them with machine-gun fire, showed no mercy. When the firing ceased, several hundred German corpses littered the bridge.

From a command bunker on the north bank, 10th SS Panzer Division commander Harmel realized that the loss of the bridge was inevitable. From his perspective, Allied artillery fire had proved decisive, knocking out the 20mm crews that were vital to German defenses. On his own initiative, and in direct violation of Model’s orders, Harmel ordered the demolition of the bridge. “It failed to go up, probably because the initiation cable had been cut by artillery fire,” wrote Harmel.

The road bridge, the greatest prize for the 82nd Airborne, was seized from both ends just as Gavin had hoped. Cook’s paratroopers secured the north end and British tanks, after a tough fight through SS defenses in Nijmegen, thundered across the bridge from the south. Burriss was ecstatic. Realizing that the bridge was now open for British armored columns, the captain waved them on. “I kissed the tank, and told them to head on to Arnhem,” wrote Burriss.

His enthusiasm was short lived. When the tanks sat tight, Burriss inquired about the delay. A German 88mm gun was visible, he was told, and the tank column would not move against it without orders. Burriss offered his own men as infantry support but was rebuffed. He seethed with anger. “I felt betrayed,” Burriss wrote. He had sacrificed half of his company to capture the bridge and the British were stopping for fear of one gun. The epic capture of the bridge at Nijmegen, which had begun with one of the most heroic feats of war, ended with little more than an anticlimactic display of inaction.

The failure of XXX Corps to press forward on the evening of September 20 sealed the fate of the British troops in Arnhem. Even the Germans were surprised by the lack of aggression. Harmel would later explain that there were virtually no troops available to block the road to Arnhem, which was wide open to an Allied thrust. “If they had carried on their advance, it would have been all over for us,” he wrote, quipping, “[But] the English drank too much tea.”

The respite allowed SS troops enough time to tighten the noose around the bridge at Arnhem. By the morning of September 21, SS troops had seized the bridge at Arnhem and killed or captured its heroic British defenders. That same day, German troops rallied for a fresh counterattack against Nijmegen. Though the attack was beaten off, Gavin correctly deduced that the enemy was funneling fresh reinforcements into the area.

Horrocks’ XXX Corps, after attempting a breakthrough, was fought to a standstill on the road to the city. On September 25, the battered remnants of the British 1st Airborne Division were evacuated to the south bank of the Rhine. Operation Market Garden, the most audacious campaign of World War II, had ended in complete failure. The Allies suffered 17,000 casualties, of which 12,000 were airborne troops, in the failed offensive. Most of the airborne casualties were from the British 1st Airborne Division.

Blame for the disaster was widely shared. Weather had delayed subsequent airborne landings. Horrocks’ tankers, for all their gallantry, had failed to reach Arnhem when they were most needed. As for the Germans, they had fought with remarkable tenacity to thwart the Allies from reaching their homeland. Strangely enough, such ugly realities seem to have been lost on Montgomery.

The mastermind of Market Garden, despite all evidence to the contrary, was oddly enthusiastic about its outcome. In a glowing report to King George VI, Montgomery announced that he was “well pleased with the gross result of the airborne adventure.” He deliberately deceived the king when he informed him that Market Garden had been “90 percent successful.” Although the average enlisted men who fought and bled in Holland lacked Montgomery’s professional training and high rank, it is doubtful if many shared such sentiments of deluded self-aggrandizement.