By John W. Osborn, Jr.

The Germans mocked it as their largest prisoner-of-war camp, and French Premier Georges Clemenceau was hardly less withering in his opinion of the Allied stronghold at Salonika, Greece. “What are they doing?” he demanded. “Digging! Then let them be known as ‘the gardeners of Salonika.’” For the one million men who made up the Army of the Orient represented the Allies’ most polyglot force—British, French, Arab, African, Indochinese, Foreign Legionnaires, Serbs, Russians, Italians, and Greeks—it was no laughing matter. Together they languished for three years around the dreary Greek port in what military historian Brig. Gen. S.L.A. Marshall later termed “without a doubt the most ponderous and illogical campaign of World War I.” During that time, they experienced 225 days of hard fighting while enduring some of the worst political infighting and the highest disease rate of the war.

The War in the Balkans

Following the outbreak of the war in August 1914, Serbia had twice thrown back Austrian offensives, largely owing to the brilliant leadership of General Rudomir Putnik. (That Putnik was able to fight the Austrians at all was due, ironically, to the Austrian emperor: Putnik was at an Austrian health resort when war broke out and could have been legitimately interned, but Franz Joseph graciously let him return to Serbia.) With Austria openly seeking allies for a third offensive, Serbia appealed to the Allies for an additional 150,000 troops. Events would turn on the prevarications of two Balkan monarchs.

Although he looked and acted like a buffoon, it was said of King Ferdinand of Bulgaria that his “fool’s cap covered a very shrewd and persistent brain.” The Allies offered him territorial concessions to keep him neutral, but in the end his pro-German sentiments and long-held ambition to reach the Aegean Sea through eastern Macedonia brought him into the enemy camp. On September 6, 1915, Bulgaria signed a treaty with Germany and Austria to join in attacking Serbia to gain control of Macedonia. Only the leader of the Bulgarian Agrarian Party, Alexander Stambolski, had the courage to oppose the king. “This policy will not only ruin our country, but your dynasty,” he warned, “and may cost you your head.” For that dire prediction Stambolski was sentenced to death for treason, but the punishment was commuted to life in prison.

On October 5, the first Allied troops began landing 50 miles south of the Serbian border at Salonika. That same day, German and Austrian forces invaded Serbia to the north. Two days later, without a formal declaration of war, Bulgaria invaded Serbia from the east. The Serbians fought desperately, but they were disease ridden, exhausted, and so short of ammunition that they could fire only a single shell for every 50 fired by the Austrians. Belgrade fell to the Austrians four days later, and German and Bulgarian forces linked up.

Meanwhile, in a month of campaigning, the Allied force—only a third of what the Serbians had requested—managed to advance only 100 miles northward, some 40 miles from the Serbs. A Serbian general ordered to counterattack wrote his superiors: “No one can expect these troops to go on fighting, even less can they be expected to launch an offensive attack. They are too few in number, their clothes are in rags, they have no boots, and they are starving. If we do not get out soon, our scanty stock of supplies will give out. Let us retreat now, for otherwise all hell will break loose.”

A Starved Retreat

With the escape route to Salonika blocked by the Bulgarians, more than 300,000 Serbian soldiers and civilians turned west for one of the war’s great tragedies. It developed into an epic, three-week-long, 100-mile march over the mountains to Albania and the Adriatic coast. A British nurse, M.I. Tatham, who accompanied the Serbs on the march, recalled, “The stream of refugees grew daily greater—mothers, children, bedding, pots and pans, food and fodder, all packed into the jolting wagons; wounded soldiers, exhausted, starving, hopeless men and (after the first few days) leaden skies and pitiless rain and the awful, clinging, squelching mud.”

The Serbs suffered temperatures of 20 degrees below zero, rampant typhus and dysentery, and repeated assaults by hostile hill tribes. Wounded and sick soldiers were abandoned, and those falling out from sheer exhaustion were also left behind. The Serbs ate their own horses, and surgery was performed without anesthesia. In the end, some 20,000 civilians died during the retreat. The elderly King Peter rode in an oxcart, an ailing Putnik in a sedan chair (he had to relinquish command at the end of the march and died in France in 1917). Government ministers and Allied diplomats alike slept on straw along the way. Even after the survivors reached the Adriatic coast, they starved and suffered for another four months until, in April 1916, the Allies shipped 260,000 Serbian soldiers to the Greek island of Corfu for refitting, then transported them to the Allied stronghold at Salonika.

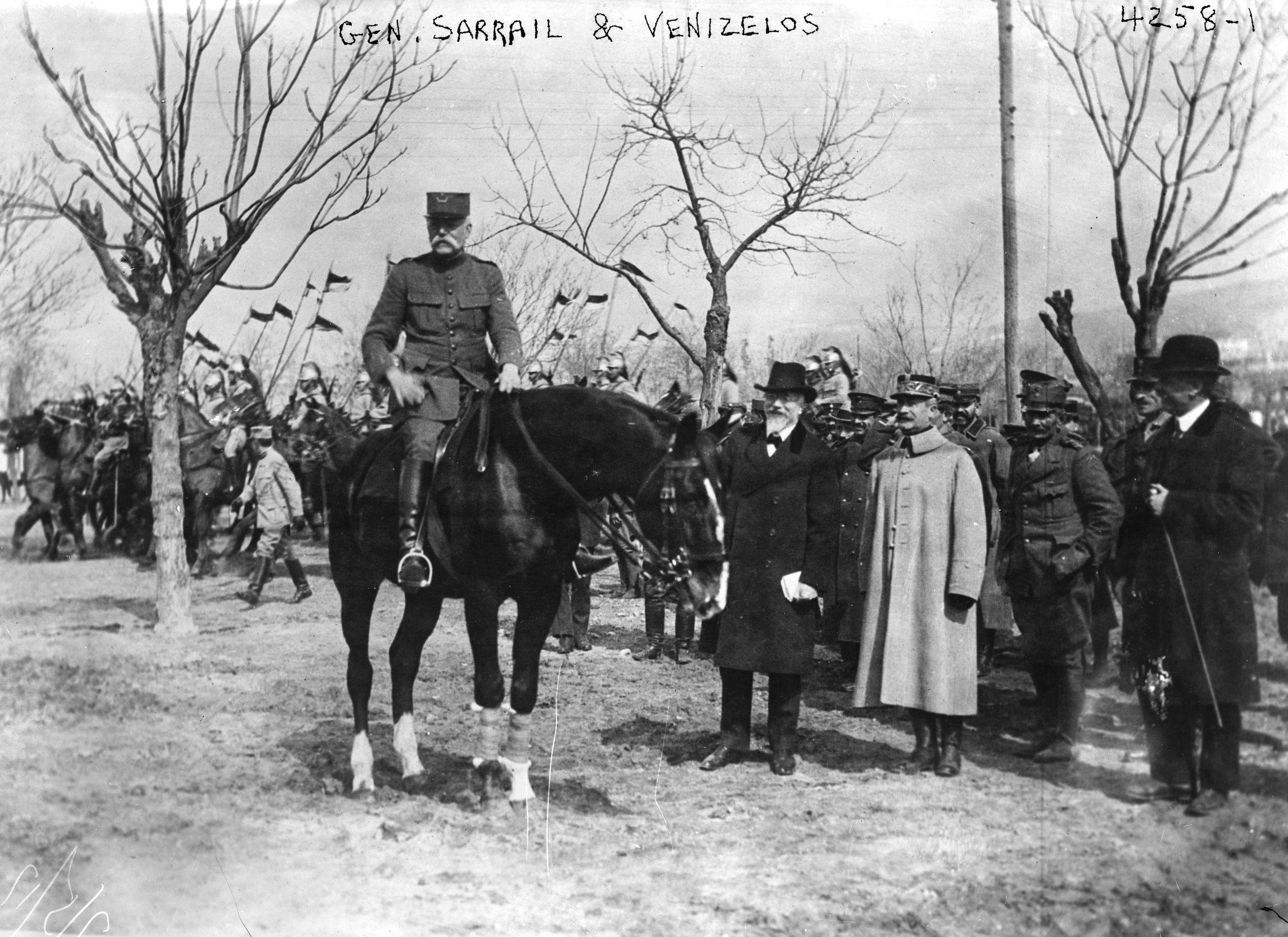

Serbian Premier Nikola Pasic blamed “the indecision and inactivity of our allies” for Serbia’s defeat, but King Peter remained defiant. “I believed in the liberty of Serbia as I believe in God,” he said. “I am tired, bruised, and broken; but I shall not die before the victory of my country.” He would have to wait. The Allied expedition to Salonika would continue to drag on for almost three years. The Serbian appeal for assistance had reached the Allies just 13 days before the invasion. The British were wary—Prime Minister Henry Asquith called it “a wild goose affair”—but reluctantly agreed to transfer the 10th Division from the Gallipoli front. The French were more forthcoming, although it soon appeared that their enthusiasm had as much to do with finding a command for a controversial general as with helping the Serbians in their hour of need. Although not without ability, General Maurice Sarrail owed his rise to his strong support in leftist French political circles. Commander in Chief Joseph Joffre distrusted Sarrail and relieved him of command of the French Third Army in July 1915. Even in the midst of world war, however, French politics remained as ideological and chaotic as ever, and to avert the type of parliamentary crisis over which French cabinets were routinely toppled, Sarrail was given the Salonika command to appease his supporters.

Political Troubles of the Salonika Expedition

Almost as soon as they began, the Allied landings were stopped in their tracks by another royal problem in the Balkans. King Constantine of Greece professed neutrality, but his motives were long suspected by the Allies—he happened to be the kaiser’s brother-in-law. Constantine was also locked in a power struggle with Greece’s leading statesman, Prime Minister Eleutherios Venizelos, who was staunchly pro-Allied. Since Greece had a treaty obligation to help defend Serbia, Venizelos favored the landings, but on the day they began and Serbia was invaded, the king suddenly fired Venizelos.

The future of the Salonika expedition teetered in the balance. The British were ready to abandon the enterprise, but the French were determined to continue. The landings at Salonika resumed, leaving the Greeks with the unpalatable choice of tacitly supporting them or fighting to stop them. With no unified command, Sarrail began moving his forces toward Serbia through the Vardar Valley; the British 10th Division followed a week later. Although easily routing the few Bulgarians they encountered, the Allied advance was slow. “All our moves have been done in inky blackness and usually under rain and on very ill-defined tracks in the hills,” 10th Division Captain G.H. Gordon wrote home.

On November 16, the Allies reached their farthest point north, where the Crna River flows into the Vardar Valley. But bad weather and the first appearance of the campaign’s worst scourge—disease—had disastrous effects on the Allied effort. The 10th Division alone reported 1,700 cases of frostbite and illness, and on December 5 the Bulgarians suddenly counterattacked. Within a week the Allies were back south of the Greek border.

The military high command in London recommended immediate withdrawal. Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George, an early proponent of the expedition, angrily told War Minister Lord Kitchener, “It seems you and the Germans want the same thing.” An English correspondent at Salonika, G. Ward Price, observed: “The Salonika expedition is not doing [the Germans] any vital harm; it is Bulgars, not Germans, who are being killed by our attacks. The German High Command knows that Salonika is a heavy drain upon the resources of the Allies.”

At an Allied conference, Asquith argued Salonika was “from a military point of view dangerous and likely to lead to a greater disaster.” The French resisted, partly for diplomatic reasons but also because of the political repercussions of relieving Sarrail. Meanwhile, Sarrail seized control of Salonika from the Greeks, expelling the enemy consulates that Athens had allowed to continue to function and spy on the Allies. Over the next four months, the Allies constructed a 70-mile-long defensive line of barbed wire, machine-gun emplacements, dugouts, and concrete positions 20 miles north of town. But while he was building up the front, Sarrail was also dividing it. His habitual arrogance and penchant for intrigue soon alienated British General Sir George Milne and the other Allied commanders.

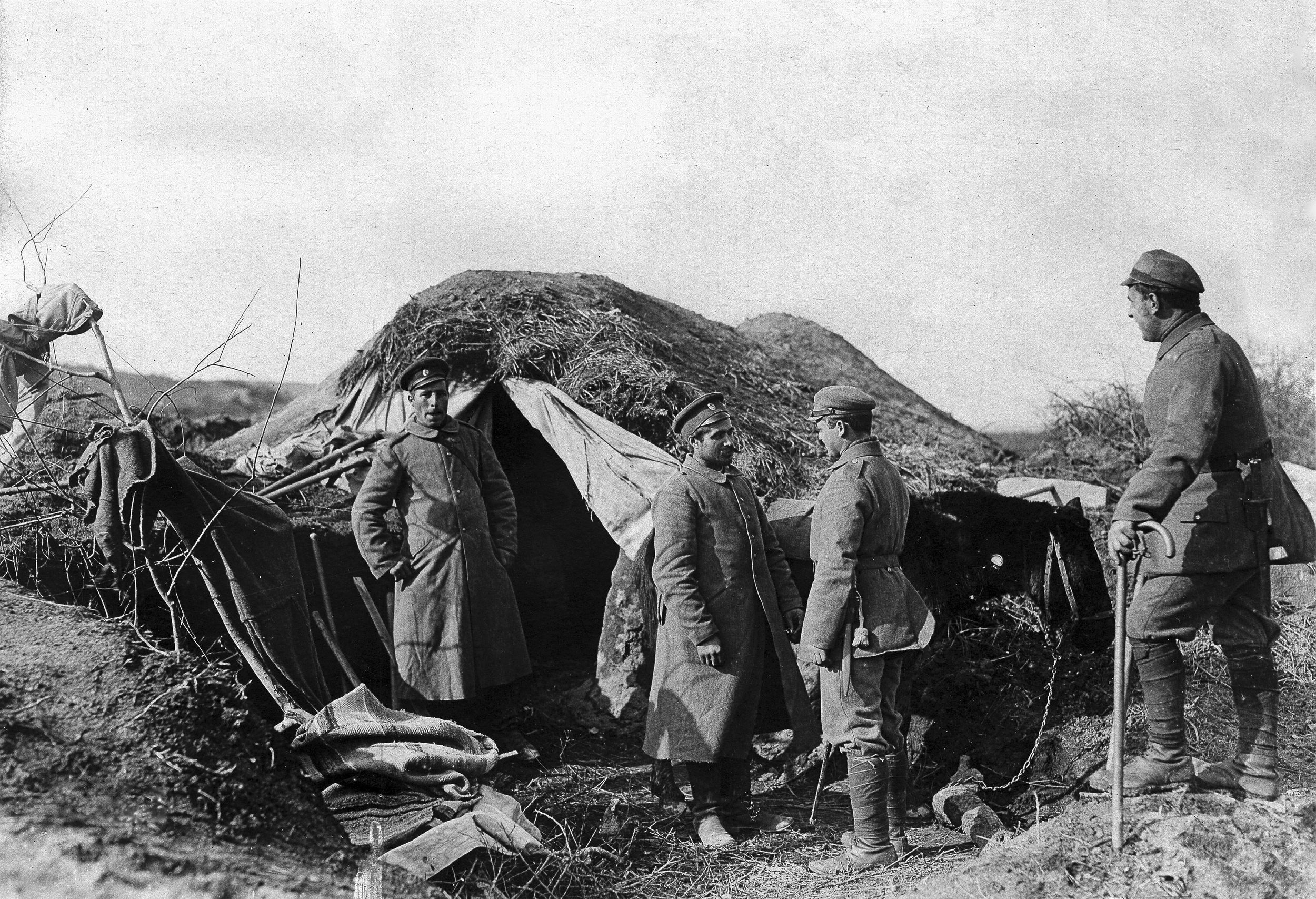

“The Birdcage”

To disgruntled British soldiers, Salonika was “the birdcage.” The troops in the front lines relieved the enforced inactivity with soccer matches for the enlisted men and fox hunts for the officers. The Bulgarians sportingly held their fire to let the Brits play soccer and sent back hunting dogs that had wandered into their lines. Occasionally, however, there were brutal trench raids between the forces. Salonika itself was a squalid riot of prostitution, alcohol, and inflated prices. Disease, both malarial and venereal, ran rampant: 20 percent of the entire British Expeditionary Corps was hospitalized in October 1917, and only 18,187 British were eventually treated for combat wounds, as compared with 481,262 treatments for disease. The French fared no better. A similar disease rate, low morale, and lack of leave led to a mutiny. Adding to the misery, a fire on August 17, 1917, gutted half of Salonika and left 80,000 people homeless. Another disaster that cemented Salonika’s hard-luck reputation occurred when a French troopship delivering 3,500 reinforcements was torpedoed, with just 200 surviving.

With the front swelled to five British divisions, four French, six Serbian, one Italian, and one Russian brigade, Sarrail planned an offensive for August 1, 1916. Inevitably, it was postponed, and the Bulgarians launched their own preemptive offensive on August 17. Bulgarian armies swept from the west down the Kenali Valley, pushing back the Serbs and capturing the Greek town of Florina, and from the east down Rupel Pass into Macedonia. Two German divisions attacked the British southwest of Lake Dorian, 40 miles from Salonika. The Serbs finally stopped the western attack in four days of hand-to-hand fighting at the town of Ostrovo. The eastern attack stalled at the Struma River line held by the British. Nine days after it started, the Bulgarian counteroffensive was over.

Sarrail finally launched his own offensive at 6 am on September 12, 1916. In 18 days of hard fighting, the Serbs took the twin peaks of Mount Kalmakcalan. The British soon stalled in the Vardar Valley, but the French and Russians under General Victor Louis Emelien Cordonnier retook Florina, drove the Bulgarians out of the San Marcos monastery, and reached the Kenali Valley on the Greek-Serbian border. But Cordonnier had another foe to contend with in his rear. He had a long-standing feud with Sarrail, who aggravated it by bombarding him with messages: “Press forward with all your forces.” “Go forward on your flank, I count on you.” “March ahead. March ahead. March ahead.”

The Bulgarians had built a strong trench system in the bare, marshy valley. Cordonnier wanted to avoid a frontal assault and even made the war’s first reconnaissance flight by a general to scout for an alternative. But upon landing, he found a preemptory order from Sarrail for a frontal assault the next morning. That assault, on October 6, and another one eight days later, failed dismally, producing 1,490 French and 600 Russian casualties. Sarrail summarily relieved Cordonnier; Milne and every other Allied commander protested the move to his own government.

Monastir fell on November 19. By his original timetable, Sarrail had intended to capture it on the eighth day of the offensive. Although the Serbs, coming from the south, had taken Monastir, Sarrial reported it to Paris as “the first French victory since the Marne.” The Serbs, conveniently unmentioned in the report, had suffered the brunt of the casualties in the offensive—27,000 men, or one-fifth of their army. British officer R.W. Imbrie found little to cheer about. “If Verdun seemed the City of the Dead,” he wrote, “Monastir was the Place of Souls Condemned to Wander in the Twilight of Purgatory.”

Assaulting Crna and the Devil’s Citadel

Winter brought the offensive to an effective halt, although it was not officially called off until December 11. In the year of Verdun and the Somme, there had been about 80 days of hard fighting along the Salonika front. With over a half million men now under his control, Sarrail planned a spring offensive along a 140-mile front aimed at the Bulgarian capital of Sofia. French, Italian, Serbian, and Russian forces were to attack on the Crna River front, while Milne offered to assault the Bulgarian positions above Lake Dorian, which commanded several major roads into Bulgaria. In so doing, Milne was taking on one of the most formidable natural fortresses in Europe, with ridges 2,000 feet above the lake upon which the Bulgarians had built defensive positions in five feet of concrete.

To make matters worse for Milne, 12 hours before his offensive was to start, at10 pm on April 24, 1917, a wire-cutting party brought in a Bulgarian prisoner who reported that the Bulgarians knew the attack was coming and had reinforced their positions. Rather than throw off the timetable for the whole offensive by delay, Milne ordered the attack to go in on schedule. The prisoner was right. The Bulgarians had brought up 33 searchlights to illuminate the battlefield. British coming up the Jumeaux Ravine south of the lake were bathed in light, then shelled; soldiers not killed by the initial explosions died when they were thrown against the walls. The Bulgarians poured machine-gun fire down on the British. At dawn, the British were ordered to retreat.

Other British attacked the first line of the Bulgarian defenses, a hill called the Petit Couronne. The Bulgarians shouted down taunts, “Come on Johnny,” but the British finally captured the lower western slopes, then held off four counterattacks. By midday it was clear that the British positions on the Petit Couronne were too exposed from fire from the upper slopes, which were still in Bulgarian hands. Again the British withdrew.

A second British assault on May 8 was another failure. Not a single Allied soldier managed to come within two miles of the Grand Couronne, the central keep of the aptly named Devil’s Citadel. Its ramparts would stand for another 16 months. In all, the assault along Lake Dorian cost the British 5,000 casualties, 25 percent of its combat losses in the campaign, with nothing to show for it but the capture of a few farmhouses across the Sturma River. By the summer the British abandoned even these, leading G. Ward Price to comment, “The only forces to hold the Sturma Valley are the mosquitoes, and their effectives may be counted by thousands of millions.”

The assaults on the Crna also ended in disaster. The Russian brigade broke through, became isolated on a hill a mile behind the Bulgarian lines, then was shelled by Allied artillery because of a communications failure. Half the brigade was killed, the other half captured. The Italians had their own communications fiasco—a cancellation order by Sarrail reached them too late for a disastrous 8 am assault. The French, with many of their men just out of hospitals, failed to press their attacks. Serbian losses along Dobropolje Ridge east of the Crna were such that their chief of staff pleaded with Sarrail to halt the offensive. He did so on May 22, but only after the misconceived offensive had cost the Allies another 14,000 casualties. In the recriminations that followed, Milne blamed bad intelligence, the Italians blamed Sarrail, and Sarrail blamed the Serbians.

The Fall of King Constantine

Sarrail’s 28-day offensive was the last major fighting on the Salonkia front until September 1918. In between, events were dominated by a ruthless power struggle in Greece and repeated reshuffling of Allied command. The front became entangled in Greek politics, as the country verged on civil war. Venizelos fled Athens ahead of the king’s order for his arrest and established a rival regime on Crete and in Salonika, where he raised his own troops to fight with the Allies. (One of his officers had a unique method of recruitment—burning down houses of those refusing to serve.) The king retaliated with a campaign of assassination against Venizelos’s supporters. “Between me and the king there is a lake of blood,” declared Venizelos.

Allied suspicions about the king’s professed neutrality hardened when the Greeks handed over key defensive positions on their border to the Bulgarians. Determined to be rid of the king for good, Sarrail organized demonstrations against him in Salonika while treating the Venizelos regime as the lawful government. After clashes with Royalist forces outside Athens during which the Allies demanded that they hand over their artillery, the Allies imposed a naval blockade on January 17, 1917. The final straw came when Constantine sent his brother-in-law—the kaiser—a message saying that he prayed for Germany’s victory. On June 1, Sarrail in turn sent him an ultimatum demanding his abdication. “I will not be treated as a tribal chieftain,” Constantine said, then left the next day for Switzerland. The crown prince went too, leaving the throne to the second son, Alexander. Back in power, Venizelos brought Greece into the war, ruthlessly purged Royalist officers, and delivered 250,000 Greek troops to the Salonika front.

“I Expect from You Savage Vigor”

The king’s downfall was followed six months later by an even less lamented event. Georges Clemenceau had become premier of France, and one of his first acts was to fire Sarrail. His successor as Allied commander in chief, General Louis Guillaumant, worked hard to restore inter-Allied relations and morale, but six months later he was recalled to be military governor of Paris. The general who was to lead the Allies to final victory on the Salonika front took over. General Louis Franchet d’Esperey had an excellent record on the Western Front and had even been considered as Joffre’s successor as commander-in-chief of the French Army, but his devout Catholicism had led him to be blocked by the same political group that backed Sarrail. D’Esperey set the tone for his leadership with his first words to the Allied officers assembled to meet him on the Salonika dock: “I expect from you savage vigor.”

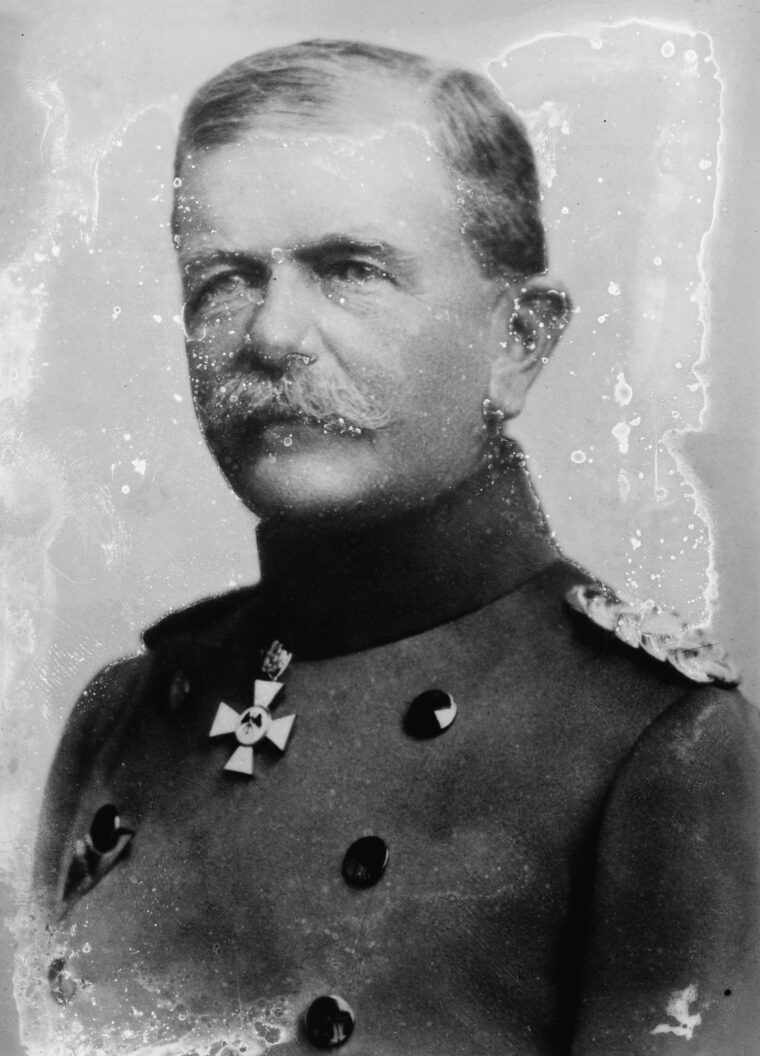

Desperate Frankie, as D’Esperey was known by the British, would get all the vigor and savagery he demanded in an offensive he launched on September 14, 1918. The offensive opened with a barrage of 500 guns. If rather small by Western Front standards, the bombardment for the Salonika front was crushing—a German general called it “an iron storm” that “approached hurricane force.” Although German General Friedrich von Scholtz commanded the front, the German presence was down to two corps. Meanwhile, the British and French had used the infusion of Greek forces to transfer thousands of troops back to the Western Front.

Knowing that the Germans and Bulgarians expected him to attack on his right, D’Esperey instead aimed for his left and center, sending the Serbs against Korzyak Mountain and the French against Dobropolje Ridge. The Serbs fought their way up the sheer rock face of the mountain in eight hours, depending on cold steel and raw courage. On Dobropolje Ridge, the French, including four Senegalese battalions, used flamethrowers in their first appearance on the Salonika front to burn out Bulgarian machine gun positions, then held their ground against five counterattacks. Adding to the kaleidoscope of nationalities making up the Allied force at Salonika was a newly formed division of southern Slavs, including Slovenes, Croats, Bosnians, Montenegrins, and Macedonians.

By September 17, the French had driven a salient 20 miles wide six miles into the Bulgarian positions around Dobropolje Ridge; the Germans began evacuating their units west to avoid being cut off. The Bulgarian commander on the ridge pleaded with King Ferdinand to make peace. He received the angry royal response: “Go out and get killed in your present lines.”

To keep the Bulgarians from rushing reinforcements to the ridge, D’Esperey ordered British and Greek forces to attack east of Lake Dorian on September 18. Fighting that day and the next, they managed to finally take the Petit Couronne and the town of Dorian, but otherwise met disaster. The British managed to fight their way to the summit of the Grand Couronne, then were driven back by intense machine-gun fire.

On Pip Ridge, British units, many of whose men were ill with malaria and were hardly able to walk, suffered 30 percent casualties. To add to their misfortune, they were caught in their own artillery barrage. Bulgarian shellfire started a grass fire that, fanned by the wind, drove the Greeks back. When the British and Greeks returned to try again on September 21, they found the Grand Couronne and Pip Ridge deserted. Von Scholtz had ordered a withdrawal along the entire front. Von Scholtz’s plan was to draw the Allies on, stretch their supply lines, then attack on their flanks. But for the Bulgarians, withdrawal almost immediately turned into panicked flight, as they abandoned their guns, stores, and supplies. The Royal Air Force remorselessly bombed and raked the fleeing columns, killing more than 700 Bulgarians in the Kosturino defile.

Invasion of Bulgaria

British forces crossed into Bulgaria on September 25. By then, war weariness and a collapsing economy had taken their toll on the country. To try to rally the troops, King Ferdinand released his old enemy Alexander Stambolski from prison and sent him to the front; 15,000 troops immediately declared a republic with him as its head. The rebellion was quickly crushed with German reinforcements and Stambolski went into hiding, but other mutinies continued to break out among the Bulgarians.

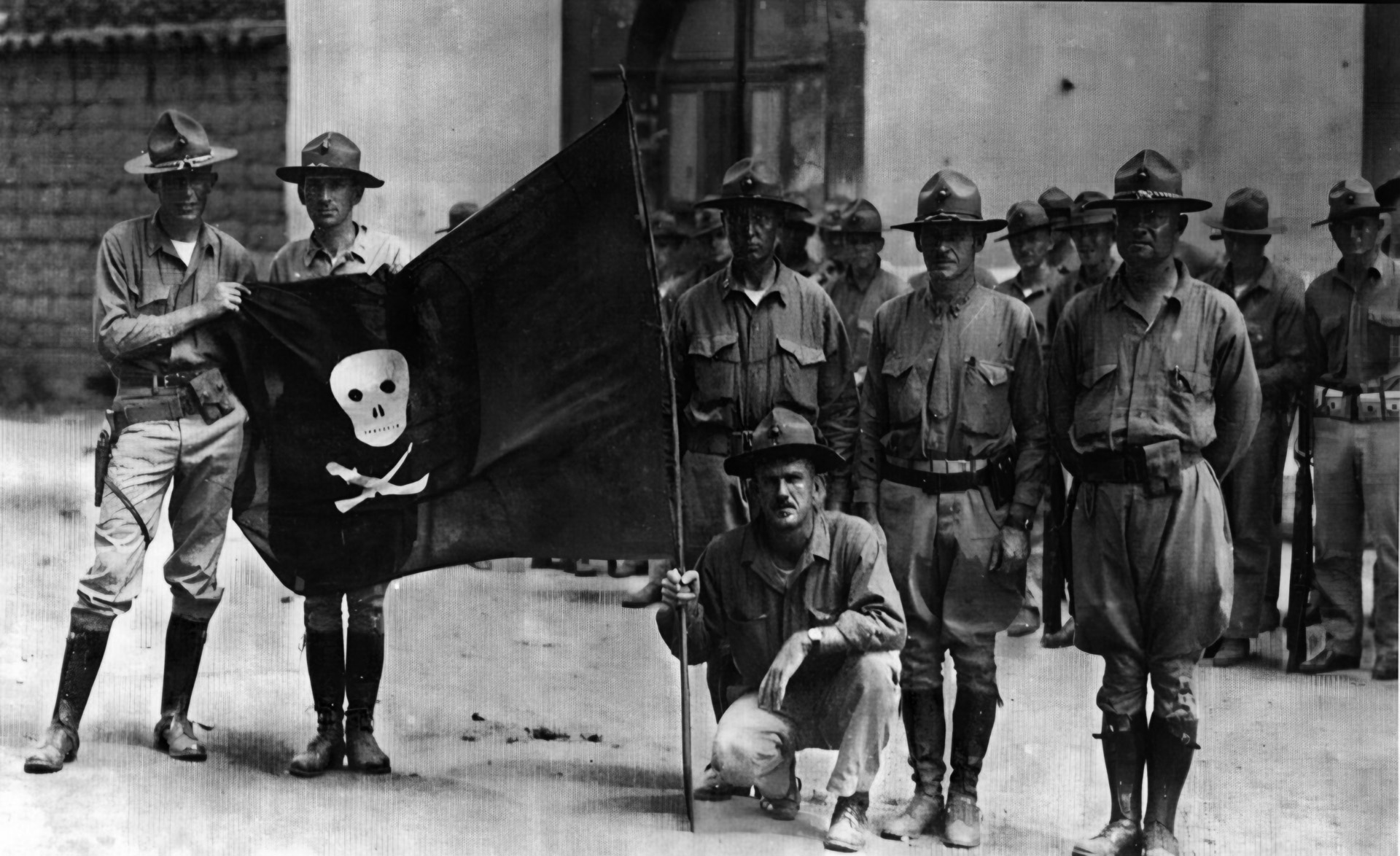

The final knockout blow to the Bulgarians would be delivered by the French. Riding in a fast car, D’Esperey had caught up with North African cavalry driving past the Crna on Prilep. He ordered them to continue 60 miles north and take Skopje, the main city of northern Macedonia. For three days the cavalry disappeared, trekking up the broken ground of the 5,000-foot Golenisca Plateau, leading their horses more often than riding them. At dawn on September 29, the cavalry came charging down on the surprised enemy in Skopje, shouting Arab war cries. The Bulgarians fled in all directions while the Germans fought back to the train station, then escaped on an armored train.

A French lieutenant described the scene in Skopje: “Ammunition dumps were exploding, shooting up red and black flames. The railroad station was aflame too. The city was full of fleeing and exhaust[ed] enemies, unable to fight.” Bulgarians were already in Salonika negotiating an armistice with D’Esperey when news of the fall of Skopje left them no bargaining room. At 10 pm that same day, the Bulgarians signed a complete capitulation, agreeing to evacuate all occupied Greek and Serbian territory, expel remaining Germans and Austrians, disarm and demobilize their army, and let the Allies use their railroads. The armistice went into effect at noon on September 30.

“The first of the props had fallen,” commented Sir Maurice Hankey, secretary of the British War Cabinet. The reaction of Germany’s de facto military dictator, General Erich Ludendorff, was more unexpected: a shrieking, foaming-at-the-mouth, falling-to-the-floor hysterical fit; a day later he was telling the kaiser to sue for peace. In the meantime, D’Esperey kept driving north into Hungary. His advance units were crossing the Danube on Armistice Day. After three years of indecisive stalemate, “the gardeners of Salonika” had advanced more than 400 miles north in seven weeks’ time.

Aftermath

The Salonika campaign cost the Allies 165,800 combat fatalities, 75 percent of them Serbian. British and French dead were 7,840 and 1,584, respectively, while Bulgaria suffered 76,729 fatalities (there are no separate figures for Germany). Although Salonika was secondary in Allied priorities, several of the participants of the Salonika campaign made out quite well. Guillaumat became French Minister of War, D’Esperey was elevated to Marshal of France, Milne became chief of the Imperial General Staff and a field marshal. The biggest Allied loser, perhaps appropriately, was Maurice Sarrail. He sat out the rest of the war, but in 1924 his still-faithful following got him a last chance, governing Syria. Within a year Sarrail had a major uprising on his hands, and was quietly relieved of his post.

Alexander Stambolski proved only partly right about his 1914 warning: King Ferdinand did lose his throne, but his dynasty continued to rule until it was driven out by the Communists after World War II. The king himself lived in peaceful exile, studying insects and birds. In that, he was luckier than Stambolski who was overthrown as prime minister, forced to dig his own grave, had an arm hacked off, and was shot by revolutionaries.

Constantine returned to the Greek throne in 1920, after his son suffered one of the most ignominious royal deaths in history (he died from blood poisoning after he was bitten by a pet monkey). Three years later, Constantine again was forced into exile, this time by a homegrown revolution, and he died a few weeks later. Eleutherios Venizelos was named prime minister of the republic that followed, before being driven into exile himself by the military.

King Peter finally returned to a liberated Serbia that, with the Austro-Hungarian Empire destroyed, expanded with the southern Slav lands to form Yugoslavia. His grandson would be driven out by Adolf Hitler and kept out by Marshal Josef Broz Tito, eventually dying drunk and near destitute in Los Angeles in 1970. The seeds of Yugoslavia’s post-Communist disintegration into civil war and its descent into horrific ethnic cleansing could be said to have been planted—however inadvertently—by “the gardeners of Salonika.”

Not lnterested in WW1

Lol insightful feedback!

Entire war was an illogical exercise for dying monarchies and up and coming dictatorships. Our involvement was totally unnecessary except for the feckless performance of Wilson during the 1914-16 period. Great Britain should have confined itself to its treaty obligations to defend Belgium and supply, but not fight, with the French. Russia should simply have gone on static defense and forget about Serbia. Clearly, national and military stupidity was the order of the day for everyone involved.