By William E. Welsh

The Union soldiers of Colonel Harrison Fairchild’s brigade prepared to attack uphill against a key Rebel position on the outskirts of Sharpsburg at 3 pm on September 17, 1862. Sensing their intention, Rebel gunners sent shot and shell in their direction. While waiting for the order to advance, the Yankees lay down to avoid being wounded or killed by the exploding shells that burst overhead and bounced along the ground toward them.

“Get up the 9th!” shouted Lt. Col. Edgar Kimball to the Zouaves of the 9th New York. The men had no choice but to obey his command. Similar orders rang out to the men of 89th New York and the 103rd New York.

“I turned over quickly to look at Kimball, who had given the order to advance, thinking he had become suddenly insane, never dreaming that he would think of advancing into that fire, and firmly believing that the regiment would not last one minute after the men had got fairly to their feet,” wrote Lieutenant Matthew Graham, Company A, 9th New York.

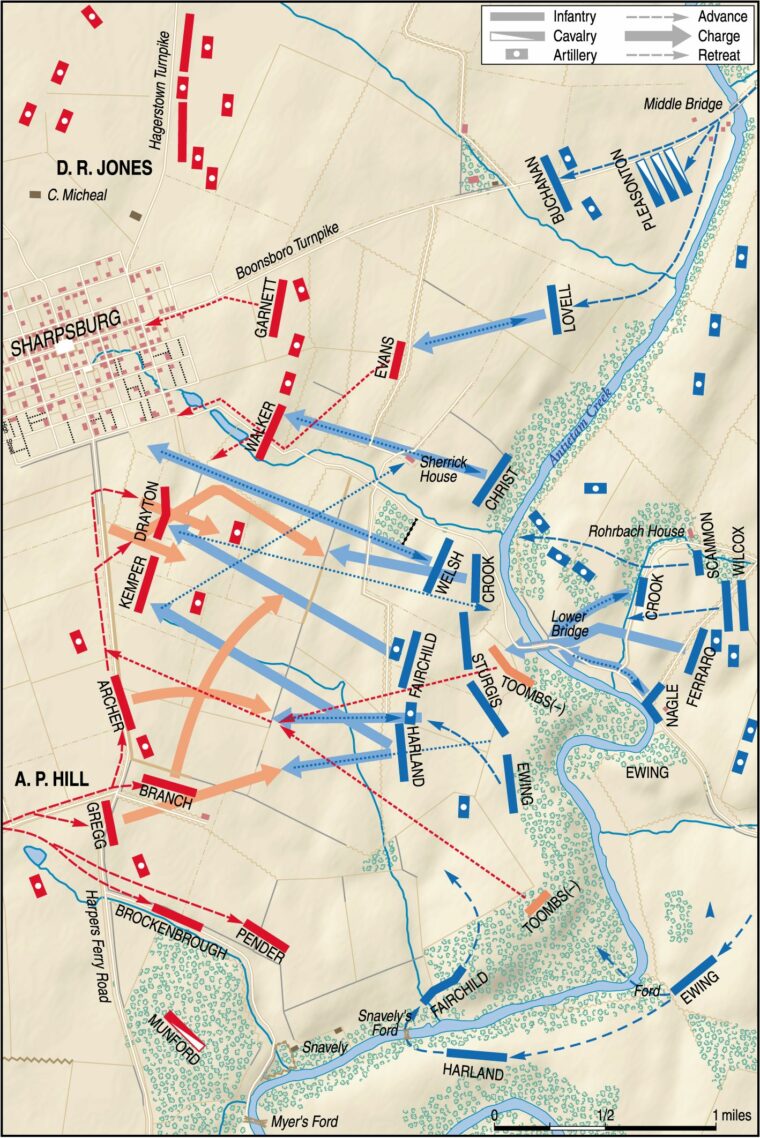

Major General George B. McClellan, commanding the 87,000-strong Army of the Potomac, had begun his attack against Robert E. Lee’s 38,000-man Army of Northern Virginia on September 17 with a series of piecemeal attacks by three Union corps—I, II, and XII—against Lee’s left flank astride the Hagerstown Turnpike north of Sharpsburg. Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, the commander of Lee’s II Corps, skillfully parried the enemy thrusts, albeit with heavy reinforcements from Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps, which Lee had tasked with defending the ground east and south of the town.

The action shifted at midday to the Sunken Road, a heavily eroded farm lane that bypassed the town to the east, connecting the Hagerstown and Boonsboro Pikes. Although Confederate Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill had conducted a masterful defense of the lane, his thin gray line had been driven out by Maj. Gen. Edwin Sumner’s II Corps.

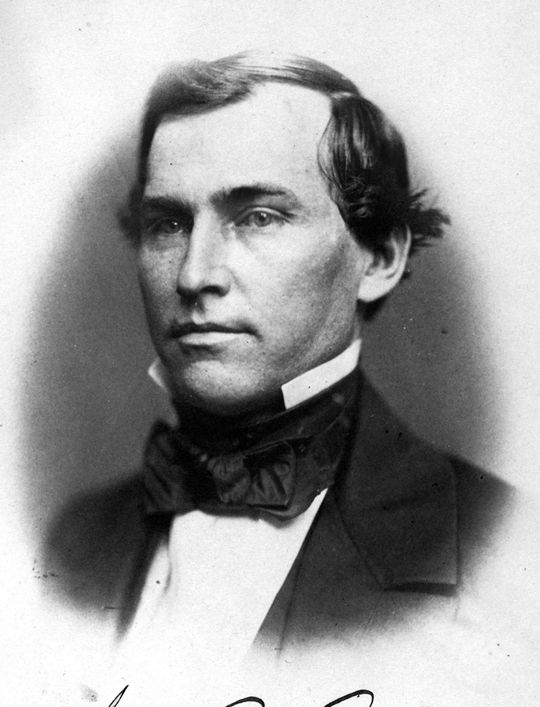

With both sides exhausted from the fighting in those two sectors, the onus fell upon Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, commanding the forces on the Union Army’s left, to press his attack on Sharpsburg. Burnside had entrusted command of his IX Corps to Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox so that he could focus on his responsibilities as right wing commander.

In the march through South Mountain to Antietam Creek, McClellan had given Burnside command of the army’s right wing and entrusted him with command of both the Union I and IX Corps. But once the Union army reached the creek, McClellan removed Hooker’s I Corps from Burnside’s control, leaving him with only his IX Corps. Cox had offered to resume command of his Kanawha Division so that Burnside could return to command of his IX Corps, but Burnside clung to his elevated post.

Throughout the long hours of September 17, McClellan’s orders went to Burnside, who forwarded them to Cox, who in turn issued orders to his four division commanders: Brig. Gens. Orlando B. Willcox, Samuel D. Sturgis, and Isaac Rodman, as well as Colonel Eliakim Scammon, who commanded the attached Kanawha Division. This extra layer at the top of the command chain contributed to the slowness of the IX Corps attack.

Burnside allowed four precious hours to slip by on the morning of the battle. He launched two attacks against the Confederates defending the Rohrbach Bridge over the lower section of Antietam Creek, but the Confederates repulsed both of them. Just when McClellan was on the verge of removing Burnside from command, two regiments of Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero’s brigade of Sturgis’s division carried the stone bridge.

At 12:30 pm 670 bluecoats from Colonel John Hartranft’s 51st Pennsylvania and the Colonel Robert Potter’s 51st New York charged down from the hill side by side. The New Yorkers were on the left and the Pennsylvanians on the right. Minie balls and shells tore into their ranks, and they halted to take cover. After a short time, Potter shouted to his men to follow and some of the New Yorkers rushed onto the bridge. Not to be outdone, a group of Pennsylvanians joined them. They made it across and sought cover. Once the Yankees established a toehold on west side, two regiments of Georgians defending the crossing withdrew. More Union troops rushed across, expanding the bridgehead. In the four-hour ordeal at the bridge, the Union lost 500 men, and the Confederates lost 125 men. At the same time the bridge was captured, Rodman led his 3,200-man division through Snavely’s Ford downstream from the Rohrbach Bridge.

Burnside had just barely avoided being removed from command for incompetence. McClellan had sent a member of his staff, Colonel Thomas Key, to observe the progress of the attack and, if Burnside did not get his men across in strength by the early afternoon, Key was to present orders to Burnside informing him that he was relieved of command. Fortunately for Burnside, he avoided the humiliating demotion.

Colonel Harrison S. Fairchild’s brigade crossed first at Snavely’s Ford followed by Colonel Edward Harland’s brigade. Spearheading the thrust were the colorful Zouaves of the 9th New York. The bluff on the far side was held by two companies of Lt. Col. Francis Kearse’s 50th Georgia of Brig. Gen. Thomas Drayton’s brigade. The 220 Georgians, who were protected by a stone wall near the top of the bluff, fired on the New Yorkers as they waded across in twos through the waist-deep waters.

Fairchild issued orders for the men not to engage the Rebel pickets while they were crossing the stream. This was done to get the troops across as quickly as possible. As the Zouaves reached the opposite bank, they turned right and marched away from the stone wall under cover of a steep wooded ridge toward Rohrbach Bridge to link up with Sturgis’s division.

As Fairchild’s three regiments began ascending the bluffs near the bridge, they heard a heavy roll of musketry from the ford. The 4th Rhode Island of Harland’s brigade had received orders to drive off the Georgians contesting the crossing. The Rhode Islanders made quick work of the task, and the Georgians withdrew at the double quick to a new line behind a stone wall that bordered the western side of John Otto’s 40-acre cornfield. They were joined there by Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs’s 2nd and 20th Regiments—the two regiments that had defended the Rohrbach Bridge—and a battalion of the 11th Georgia of Colonel George T. Anderson’s brigade.

Toombs consolidated his reinforced brigade to contest Burnside’s advance from the Rohrbach Bridge. Some of the troops under his command had contested the crossings of the Lower Antietam, while others had been detailed to guard Confederate supply wagons on the west side of the creek from a possible Union cavalry strike.

Toombs’s four regiments—the 2nd Georgia, 15th Georgia, 17th Georgia, and 20th Georgia—were supplemented by the 50th Georgia of Brig. Gen. Thomas Drayton’s brigade and five companies of the 11th Georgia of Colonel George T. Anderson’s brigade. Anticipating that the Federals might try to outflank him in Otto’s cornfield, Toombs ordered the regiments under his command to fall back to the Harpers Ferry Road where the only troops defending the extreme right flank of Lee’s army were the regiments of Colonel Thomas Munford’s cavalry brigade.

Burnside’s IX corps squandered more precious time preparing to move out from the Rohrbach Bridge. Sturgis’s division deployed on the right astride the Rohrbach Bridge Road to Sharpsburg, and Rodman’s division assembled on its left. Colonel Hugh Ewing’s First Brigade of the Kanawha Division supported Rodman’s left wing, and Colonel George Crook’s brigade of the Kanawha Division supported Sturgis’s right wing.

Burnside issued orders detailing the right wing to advance directly against Sharpsburg and for the left wing to block Lee’s line of retreat into Virginia via Boteler’s Ford on the Potomac River. McClellan advised Burnside that once he began pressing his attack against Sharpsburg he would receive substantial support from Fitz John Porter’s Union V Corps. It would turn out to be a hollow promise.

After an hour getting the troops of Sturgis, Rodman, and Scammon across the Antietam, Cox discovered that Sturgis’s troops had severely depleted their ammunition trading fire throughout the morning with the Confederates defending the Rohrbach Bridge. Cox, who was on the west side of the creek overseeing preparations for the advance, requested that Burnside send Willcox’s division across the Rohrbach Bridge to take the place of Sturgis’s division. The request was made at 2 pm. It took another hour to substitute Willcox’s men for Sturgis’s men. Sturgis’s men shifted to the rear where they replenished their ammunition and served as a reserve.

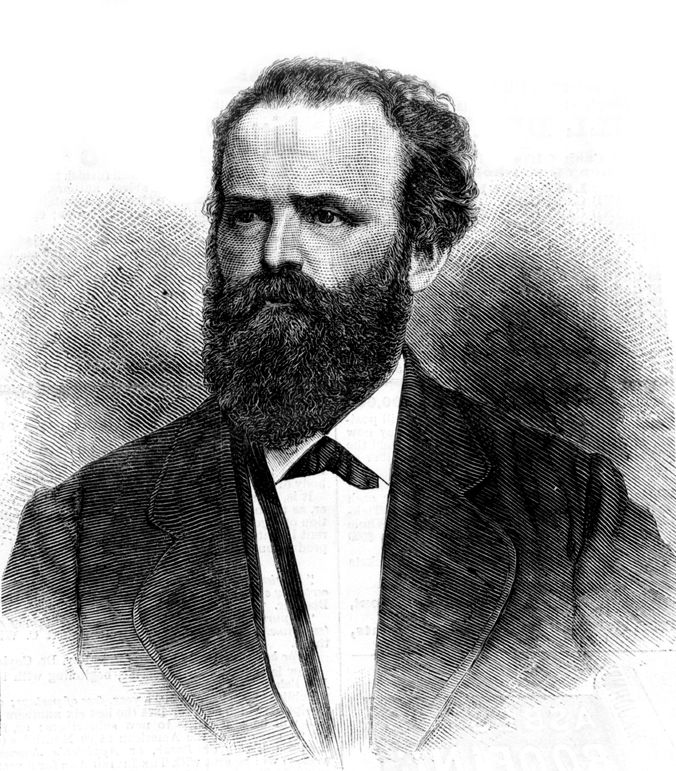

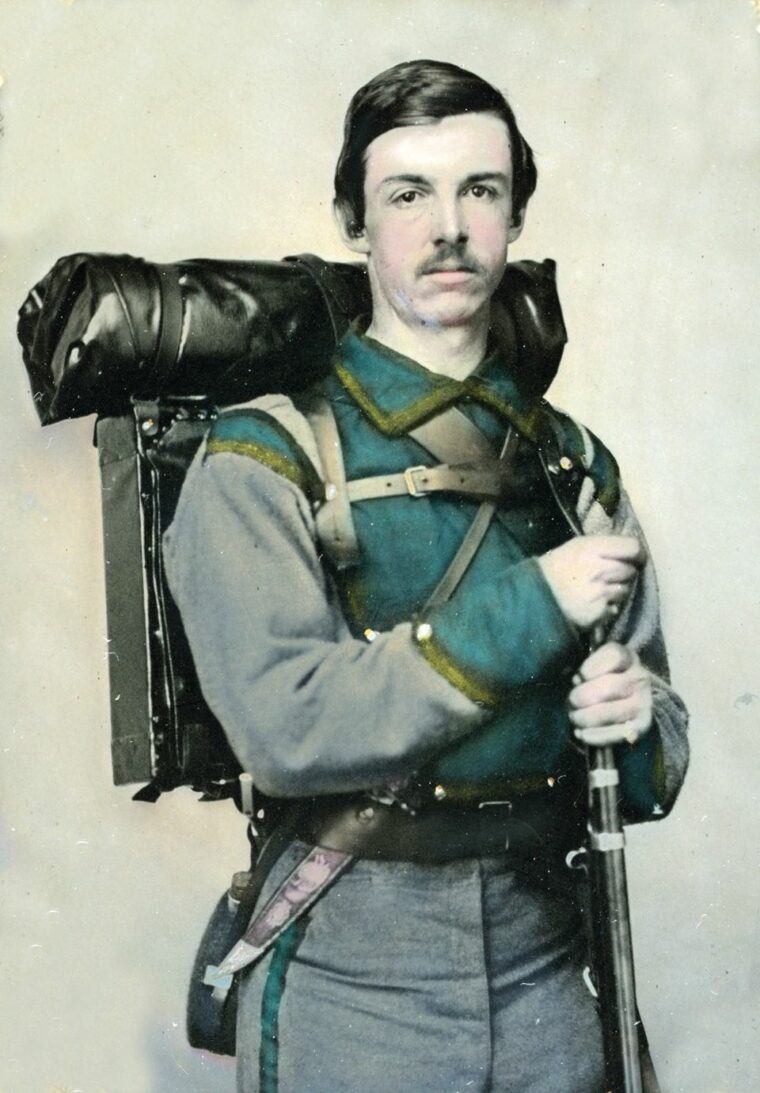

Lieutenant Colonel Edgar Kimball, who was 38 years old at the time, commanded the colorful Zouaves of the 9th New York. Known as “Hawkins Zouaves,” after politician-turned-soldier Rush Hawkins who founded the regiment, the men wore baggy trousers, short blue jackets, and fezzes, which were in vogue at the time, mimicking the world-famous Algerian Zouaves in the French colonial army.

The 9th New York had served throughout the first half of 1862 in Union operations against the Confederate coastal strongpoints in North Carolina, but on September 4 it arrived in Washington and proceeded to Frederick, Maryland, to join Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. The Zouaves’ combat experience was limited, as reflected by their having suffered minimal casualties during their time on the North Carolina coast.

The terrain on the west side of Antietam Creek rose steeply in a series of terrace-like elevations up to the high ground where the Harpers Ferry Road was situated. The Rohrbach Bridge Road ran north from the bridge and then turned west up a ravine through which a spring branch emptied into Antietam Creek. The road through the ravine was flanked on each side by large farms. These farms were stitched by stone and post-and-rail fences and contained orchards, haystacks, and cornfields that furnished excellent cover for Confederate skirmishers and sharpshooters.

Brigadier General David R. Jones’s division had about 2,500 men to contest the 9,000 men of the IX Corps. What the Confederates lacked in infantry in that sector they hoped to make up for in artillery. The Confederate batteries on or near the Harpers Ferry Road were positioned 40 to 70 feet higher than the four Union batteries that unlimbered on the west side of the creek to support the IX Corps advance. Thus, the Confederate batteries defending the approaches to Sharpsburg commanded the ground over which the Union infantry would be attacking.

Fairchild’s troops assembled in a swale beneath the batteries of Captain George Durell’s Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery D, and Captain Joseph Clark’s 4th U.S. Artillery, Battery E. These two batteries of 10-pounder Parrott rifled guns soon became engaged in a tense duel with the Rebel guns along the Harpers Ferry Road.

Fairchild’s brigade deployed in a long line in front of the two Federal batteries and between Harland’s brigade to their left and Colonel Thomas Welsh’s brigade of Willcox’s division to their right. From left to right, Fairchild’s three regiments—totaling 940 men—were Major Edward Jardine’s 89th New York, Major Benjamin Ringold’s 103rd New York, and Kimball’s 9th New York.

Fairchild’s field officers paced up and down behind their prone men anxiously awaiting orders from Rodman to advance. Rodman told Fairchild to deploy skirmishers and begin his advance once they were in position. Fairchild’s objective was the Rebel batteries along the Harpers Ferry Road. His men would have to cover 800 yards under intense artillery fire to reach the guns.

The Confederate artillerists were firing round shot and case shot at the two Federal batteries. Many of the rounds overshot their target and landed amid the infantry lying prone nearby, causing great anxiety among the troops.

“The practice of the Rebel artillery men was something wonderful in its accuracy,” recalled Lieutenant Matthew Graham of the 9th New York. “They dropped shot and shell into our line repeatedly. They kept the air fairly filled with missiles of every variety. I watched solid shot … strike in front of the guns with what sounded like an innocent thud, and bounding over the battery and park, fly through the treetops, cutting some of them off so suddenly that it seemed to me they lingered for an instant undecided which way to fall.”

The two Confederate batteries that were dueling with Clark’s and Durrell’s batteries were Captain James Brown’s Wise Artillery of Virginia and Captain James Reilly’s Rowan Artillery of North Carolina. Brown contributed four light 6-pounders, and Reilly had a two-gun section of powerful 24-pounder howitzers in action.

Also lending artillery support against Fairchild’s advance was Captain John B. Richardson’s 2nd Company of the well-regarded Washington Artillery from Louisiana. Richardson had a battery of Napoleon 12-pounder smoothbores in action on the far side of the Harpers Ferry Road. His battery was deployed several hundred yards to the southwest of Brown’s and Reilly’s guns.

Lying in support on the reverse slope of ridge behind the Confederate guns were elements of Drayton’s Georgia Brigade and Brig. Gen. James Kemper’s Virginia Brigade. Neither Drayton nor Kemper were commanders of any particular note. Following the Battle of Fredericksburg, Confederate General Robert E. Lee helped arrange Drayton’s transfer to the Trans-Mississippi Theater, a fate reserved for those Lee deemed third-rate commanders. Kemper was wounded in Pickett’s Charge and afterward played no further role in Lee’s army.

Only three of Kemper’s five regiments, the 1st, 11th, and 17th, were available to contest Fairchild’s advance. The other two regiments, the 7th and 24th, had been detached at noon to guard the extreme right flank of the Confederate army; however, Major Arthur Herbert’s 7th Virginia returned in time to participate in the defense of the ridge. Kemper assigned the Herbert’s men to serve as skirmishers. They moved downhill to contest the intervening ground.

These men were deployed in a protected position on the Avey Farm on the outskirts of Sharpsburg. A 300-yard-long fence enclosing the Avey orchard was built of different materials. The northern section of the fence was stone and the southern section was wood. The Confederate brigadiers planned to move their men forward to the fence line when the Yankees were closer. But for the time being, they stayed out of sight. Drayton’s men would defend the stone section, and Kemper’s men would defend the post-and-rail extension of the fence.

Rodman ordered his troops to advance at 3:30 pm. The regimental commanders shouted the order to advance. The men shed their knapsacks and fell into line. Fairchild’s brigade was arrayed for attack with two regiments forward and one in reserve. On the left was the 89th New York, and on the right was the 9th New York. Ringold’s 103rd New York formed the second line.

Fairchild and his regimental commanders planned to advance in short spurts toward their objective. The regiments would move at the double quick and then halt in a depression or ravine to realign before resuming their advance. The same method was used effectively by Welsh’s brigade on Fairchild’s right flank.

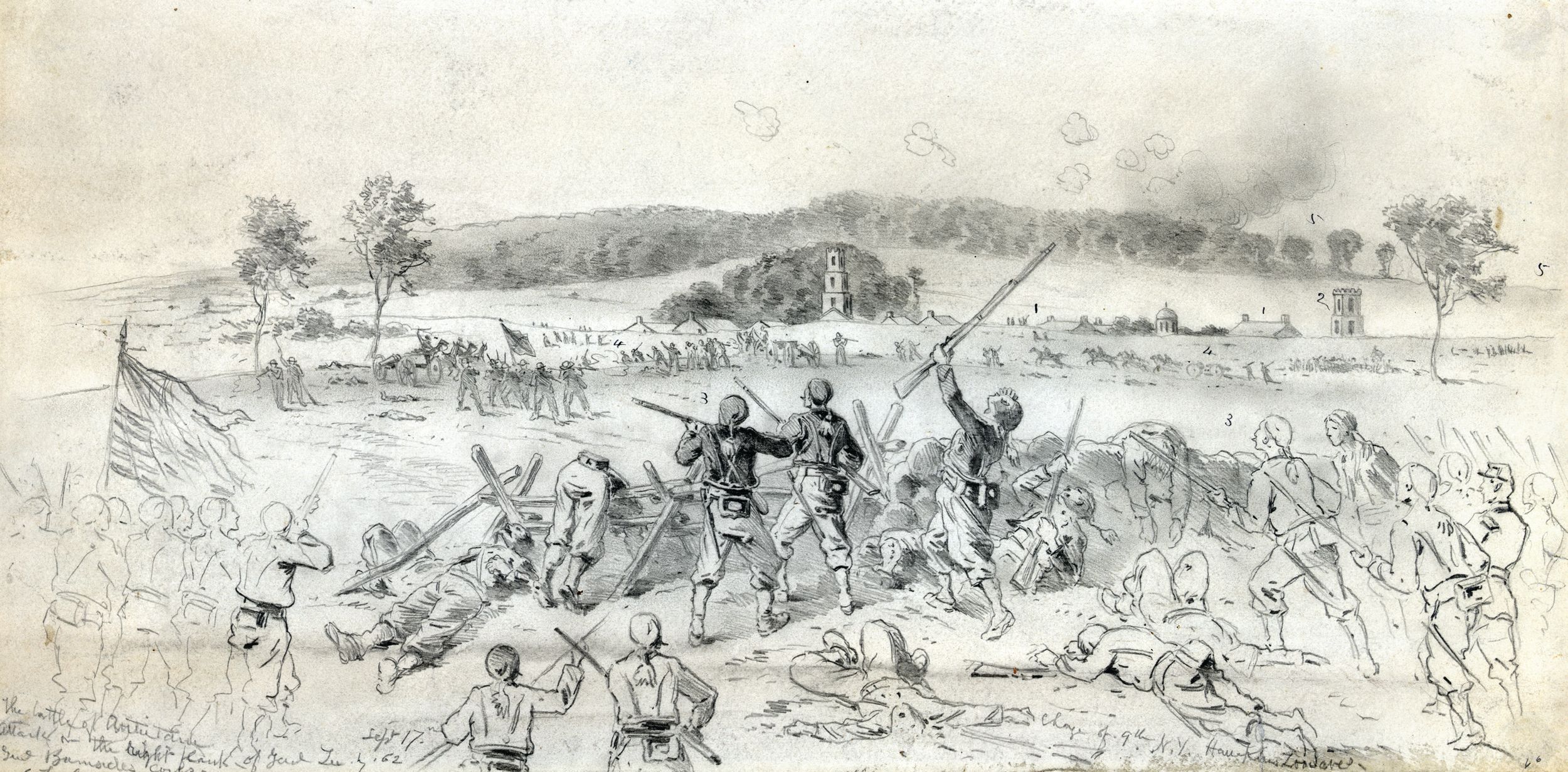

The three regiments lowered their heads as they advanced into a storm of iron from the Confederate artillery. The first obstacles they encountered were the post-and-rail fences lining John Otto’s farm lane. They quickly climbed the fences and pushed into a meadow beyond the farm road. By that time they had covered about one-quarter of the distance to the high ground where the Rebel guns were situated.

As they advanced, Herbert’s Rebel skirmishers kept up a steady fire. Musket balls zipped through the air and artillery shells tore large gaps in the lines. Under this brutal bombardment, the Yankees passed through a ravine and into a meadow. By this time, their ranks were beginning to thin considerably from the enemy fire. This winnowing of their ranks ultimately would force Ringold’s New Yorkers to squeeze into the center of the main line.

Upon entering the meadow, the regimental officers halted their men in a furrow to dress their lines. The men lay flat to avoid the enemy fire. Showing no fear of the storm of artillery shells bursting all around him, Colonel Kimball strode back and forth along their lines shouting encouragement. “Bully 9th!” I’m proud of you! Every one of you!”

At that point, Fairchild ordered his line to charge the enemy. “Huzzah!” the New Yorkers shouted as they swept forward at the double quick. Another obstacle loomed before them. The left and center of the line had to pass over a long stone wall that extended from Otto’s cornfield toward his house before ending abruptly short of a ridge. Many of Herbert’s skirmishers had used the stone wall to good effect, but when the long blue line reached the wall it scattered the Virginians like loose leaves in an autumn wind.

A fresh Confederate battery had unlimbered to the southwest and joined the furious bombardment intended to break up Fairchild’s attack. This was Captain David McIntosh’s Pee Dee (South Carolina) Battery, which was part of the vanguard of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Light Division. Hill’s command began arriving one brigade at a time on the southern end of the battlefield after a grueling 17-mile forced march from Harpers Ferry. McIntosh ordered his teams off the road at the Blackford Farm. Leaving a howitzer and his caissons near the farm, he accompanied his crews to a nearby ridge overlooking the Harpers Ferry Road. His artillery crews dropped trail on a pair of rifled guns and a 12-pounder smoothbore. More shells screamed down on Fairchild’s Federals.

One Rebel shell killed eight Zouaves at once, sending equipment and body parts flying through the air. Despite the storm of iron, the New Yorkers continued on toward the ridge. As they swept on, they shouted, yelled, and cursed as they closed the gap between themselves and the Rebel guns.

Private John Dooley of the 1st Virginia estimated that as many as 2,000 Yankees were headed toward the ground held by Kemper’s and Drayton’s men. His estimate was more than double the actual strength of the blue-uniformed lines sweeping uphill. The feeling that they were outgunned was exacerbated by the dearth of Confederate infantry in the sector. “There may have been other troops to our left and right but I did not see any,” he said.

Fairchild’s troops halted briefly before covering the final 100 yards through a shallow vale and up the slope to the enemy’s guns. The Yankees would have to ascend the last slope to reach the Confederate position. They had no idea that Confederate infantry was about to spring into action.

The ridge where the Confederate guns had been situated was 70 feet above their position. As it leaves Sharpsburg, the Harpers Ferry Road runs along this high ridge. The ridge’s northern end abuts the spring branch that swings past the town on its north side to tumble downhill to Antietam Creek.

“Our position was directly in front of the village of Sharpsburg, on a high hill, behind a new post and rail fence,” wrote Private Alexander Hunter of the 17th Virginia of Kemper’s brigade. “The topography of the country and the configuration of the ground was peculiar, consisting of a succession of undulating hills and corresponding valleys. The elevation that we were on sunk rather abruptly to a deep bottom, and then rose suddenly, forming another hill, the crest of which was about 60 yards from the top of the eminence where we rested. Any attacking force would be invisible until they arrived on the top of the crest opposite, and in pistol-shot distance, or what we call point-blank musketry range.”

For the assault against the flat ridge, Fairchild had 700 men remaining from the original strength of 940 at the start of the assault. At that point, the Confederates moved into position behind their respective fence positions. The Georgians filed in on the left behind the stone fence, and Kemper’s Virginians filed in on the right behind the post-and-rail fence. Kemper had 210 Virginians and Drayton had 380 Georgians to defend their position.

The anticipation of the pending attack made Rebel hearts beat rapidly. “Keep cool, men, don’t fire yet,” Colonel Montgomery Corse told his 17th Virginia Regiment. Other regimental commanders and line officers repeated similar orders to their men the length of the Confederate line.

“The hill in our front shut out all view, but the advancing enemy was close on us, they were coming up the hill, the loud tones of their officers, the clanking of their equipments, and the steady tramp of the approaching host was easily distinguishable,” wrote Hunter.

The Rebels were filled with a sense of dread equal to that of the attacking Federals. The Yankees went to ground again in a depression a short distance from the wall to reform their ragged line.

The Confederate batteries, nestled in a plowed field atop the ridge ahead, began firing canister at the mass of blue-uniformed soldiers. Canister was invaluable as antipersonnel ammunition for Civil War artillery batteries. When the enemy closed to within 200 yards of the battery, the gunners switched to canister and loaded either a single round or two rounds, referred to as “double canister.” The casing disintegrated, spreading 1-1/8-inch iron balls in a conical formation.

“The loss was frightful,” recalled Graham. The carnage reminded him of a line spoken by Marshal Jean Lannes, the commander of the advance guard at Austerlitz, who said, “I could hear the bones crash in my division like glass in a hailstorm.” Across the path of their advance lay the mangled and contorted bodies of Yankee soldiers killed by the deadly canister fire.

By that time they had the undivided attention of the Rebel gunners who were going to great lengths to shatter their attack. “The battery [Brown’s] … had depressed its guns so as to shave the surface of the ground,” wrote David Thompson of the 9th New York. “As the range grew better, the firing became more rapid, the situation desperate and exasperating to the last degree.” While under cannon fire the Yankees let loose a torrent of cursing as they watched their friends dying around them. “Human nature was on the rack, and there burst forth from it the most vehement terrible swearing I have ever heard,” Thompson wrote. A greatcoat flew over Thompson’s head. He looked up to see a soldier in front of him lying face down in the dirt. The canister had plowed a groove across the top of his head and stripped his coat from his back, sending it flying through the air.

The Yankees received orders to fire a volley and then charge the wall with fixed bayonets. When the Union soldiers reached the stone wall, they were greeted with a crashing volley delivered at close range by the Southerners. “In a second the air was full of the hiss of bullets and the hurtle of [canister],” wrote Thompson. It was a moment of great mental strain for the Yankees, and it produced a sensation that Thompson likened to an experience had by German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in which “on a similar occasion—the whole landscape turned slightly red.”

From 50 yards apart, both sides poured fired into each other. The Rebel fire felled many Yankees. Musket balls slapped the stone fence where the Confederates were positioned. Drayton’s men set their rifled muskets atop the stone fence they defended, and Kemper’s men laid the barrels of their weapons on the lower rails of the post-and-rail fence.

The Yankees lay flat in an effort to avoid the blistering fire. The key to getting them up and moving was to advance the regimental colors. If that was done, the men would follow. But each time a group of Yankees attempted to storm the wall with their colors, they were shot to pieces. “The flags were up and down, up and down, several times in a minute,” wrote Graham. After all eight of the men assigned to the color guard of Company E of the 9th New York had been slain, Lieutenant Sebastian Myers was shot as he tried to pick them up.

After many long minutes under the galling Rebel fire, Captain Adolphe Libaire seized the regimental colors and shouted, “Up damn you, and forward!” He would receive the Medal of Honor for his valor. Libaire and three other company officers rose up and shouted for their men to follow them. The Yankees, who left many of their fellow soldiers lifeless on the field of battle, surged to the wall yelling, “Huzzah!” Waving his fez on his sword, Captain Robert McKechnie urged his men forward. At the wall the opponents, crazed by the wild nature of the fighting, began to fight with clubbed muskets. Bayonets flashed in the fading sunlight as the Yankees sought to pry the Rebels from the fence line. Some of the Yankees scrambled over the fence, and soon the Rebels found themselves outnumbered and unable to fend off the determined assault.

“We stood up against this force more from a blind-dogged obstinacy than anything else, and gave back fire for fire, shot for shot, and death for death,” wrote Hunter. “But it was a pin’s point against Pelides’ spear.”

Fairchild’s brigade paid a high price in blood for the key position it captured. Of the 940 men participating in the attack, 455 were killed or wounded. Their loss was worth it, though, for it precipitated a general collapse of the Confederate right flank. Only the imminent arrival of Hill’s Light Division could stave off defeat for Lee’s army.

The survivors of Drayton’s brigade fled through the Avey orchard into Sharpsburg, while Kemper’s remaining troops fell back through the cornfield adjacent to the orchard. “We were forced to retire in great disorder leaving the enemy in possession of our position,” said Dooley. “Hastily emptying our muskets into their lines, we fled back through the cornfield.”

The Confederates ran west toward the Harpers Ferry Road. Dooley said that his 9-pound rifled musket, his heavy belt, and his cartridge box weighed him down so badly that he was only able to run at half his potential speed. “I was afraid of being struck in the back, and I frequently turned half around in running, so as to avoid if possible so disgraceful of a wound,” said Dooley. Glancing backward from time to time as he ran, he could plainly see the elation of the Yankees at having captured their objective. “The enemy … appeared to think they had performed wonders,” he said bitterly. As for Hunter, he and two of his fellow soldiers were taken prisoner.

To the north, Willcox’s division was making steady progress toward Sharpsburg. Welsh’s brigade advanced along the south side of the Rohrbach Bridge Road, while Colonel Benjamin C. Christ’s brigade advanced on the north side of the road.

About 400 yards beyond the Otto house were a stone house and stone mill situated on the north and south sides of the road, respectively. Welsh ordered Lt. Col. David A. Leckey, the commander of the 100th Pennsylvania, to deploy his regiment as skirmishers and lead the brigade’s advance. The Keystone Staters pushed steadily uphill through the fields of the Otto Farm on the south side of the Rohrbach Bridge Road toward the mill beyond it.

Welsh’s main battle line followed the 100th Pennsylvania. The 8th Michigan held the left, the 46th New York the center, and the 45th Pennsylvania the right. The left of Christ’s line collided with the 15th South Carolina of Drayton’s brigade, which was deployed in open order as skirmishers, and forcefully drove it back.

Contesting the advance of Christ’s brigade north of the Rohrbach Bridge Road was Colonel Joseph Walker, who commanded the brigade of Brig. Gen. Micah Jenkins, who was recuperating from a severe wound inflicted at the Battle of Second Manassas. Walker’s five South Carolina regiments were deployed on the slope of Cemetery Hill on the eastern outskirts of Sharpsburg. Also contesting Christ’s advance was Colonel Fitz W. McMaster of the 17th South Carolina of Brig. Gen. Nathan Evans’ brigade. McMaster commanded his regiment, another regiment known as the Holcombe Legion, and a detachment of the 1st Georgia from Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson’s brigade.

McMaster’s butternuts found themselves heavily outnumbered and having to fend off attacks by both of Willcox’s brigades. On the north side of the road, McMaster’s Confederates traded shots with the men of Lt. Col. David Morrison’s 79th New York of Christ’s brigade. Morrison’s men fought as skirmishers in open order in two lines. Morrison was supported by Christ’s main battle line consisting of the 28th Massachusetts, 50th Pennsylvania, and untested 17th Michigan. On the south side of the road, the 45th and 100th Pennsylvania captured the mill and advanced jointly against the remaining Confederate infantry on the last ridge before Sharpsburg.

The long Federal line overlapped McMaster’s much shorter line, and he ordered his troops to fall back on the stone house and mill. Rebel case shot screamed down on the Yankees, slowing their pursuit of McMaster’s men and buying the South Carolinians and Georgians time to rally. McMaster’s men put up a stout defense in the large apple orchard on the north side of the road. Christ’s troops found themselves caught in vicious converging fire from McMaster’s and Walker’s troops.

At the same time that the lead regiments of Welsh’s and Christ’s brigades were trying their best to dislodge McMaster’s stubborn Confederates from the mill, Brig. Gen. George Sykes had begun deploying elements of his 2nd Division of the Federal V Corps across the Middle Bridge for the purpose of putting added pressure on thea Confederates defending Sharpsburg. Captain John Poland commanded 2nd and 10th U.S. Infantry Regiments probing the makeshift Confederate defense in front of and atop Cemetery Hill. Finding only a small number of Confederate infantry to impede his advance, Poland requested permission to charge them. Rather than taking advantage of the opportunity, the senior officers of the V Corps overruled the request; instead, they ordered Poland to withdraw to the Middle Bridge. This signaled that McClellan had no intention of reinforcing Burnside.

Both Welsh and Christ ultimately succeeded in clearing the Confederates defending the ridges on the eastern outskirts of Sharpsburg. Some of Fairchild’s men, as well as some of the men from Christ’s and Welsh’s brigades, cautiously pushed into the eastern edge of Sharpsburg where they traded shots with Confederate stragglers who, either by purpose or accident, had become separated from their commands and were wandering about or had taken refuge in homes and shops. Federal artillery shells had set some structures ablaze, and thick smoke from burning structures boiled into the sky. Both Christ and Welsh felt a keen sense of anxiety in their forward positions. They waited in vain for Burnside or McClellan to send troops to reinforce them and capitalize on their successes.

On the extreme left of the IX Corps line, Harland had bungled his attack. For reasons unclear, two of three regiments ordered to advance failed to do so. Consequently, Lt. Col. Hiram Appelman’s 8th Connecticut Regiment on the brigade’s right pushed toward the Harpers Ferry Road unsupported, while the 16th Connecticut and 4th Rhode Island remained on the south side of the Otto cornfield. Appelman’s regiment headed straight for McIntosh’s three guns.

As the Constitution Staters advanced toward the Rebel battery over the rolling terrain, McIntosh ordered his troops to switch targets. The skilled artillerymen loaded double canister to blast the Yankees charging their position. The guns bucked from the powerful recoil. The effect at close range was devastating. Still, the men of the 8th Connecticut advanced while loading and firing. They shot down the cannoneers and the battery horses as they approached the guns. McIntosh ordered his gunners to save themselves, and those still standing ran for safety. A Connecticut soldier, ecstatic over the triumph, leaped atop one of the captured guns.

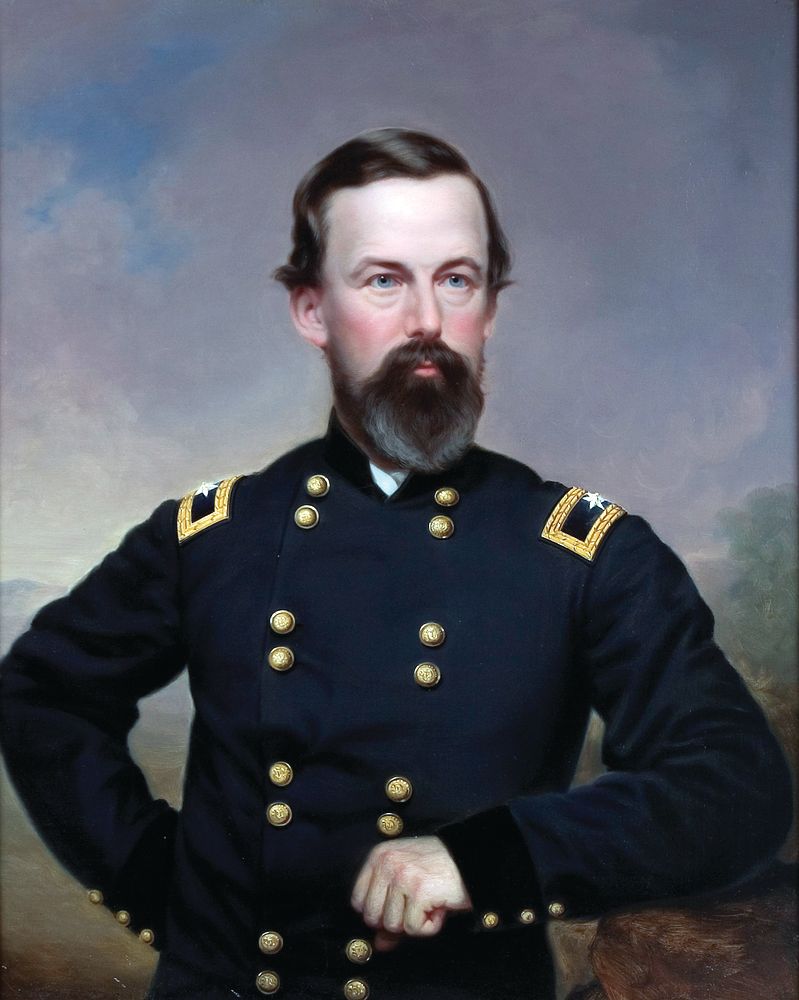

In the distance, the head of the Hill’s column arriving from Harpers Ferry could be seen by both sides. Rodman and Harland, who were following the 8th Connecticut, spotted the enemy column. Rodman galloped north to warn Fairchild. As Rodman made his way across the battlefield, a Confederate sharpshooter fired a musket ball that penetrated Rodman’s left lung, knocking him from his horse mortally wounded.

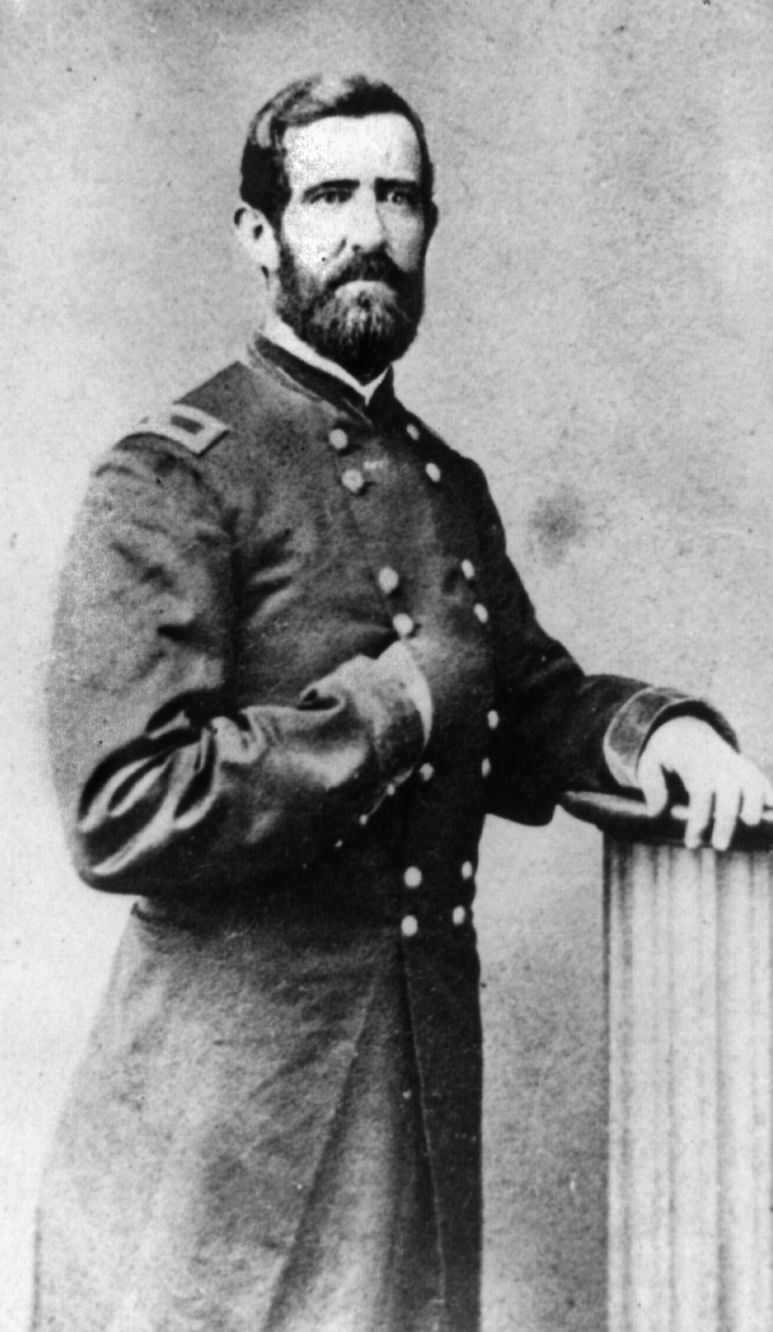

Clad in his red battle shirt, A.P. Hill had with him five of his six brigades. Only about 3,300 of his men made it across the Potomac, and of that number only about 2,000 became engaged. Large numbers had fallen out of the column from heat and exhaustion. After a brief meeting with Lee, he rode south to confer with Jones regarding where to send the forward elements of the Light Division. The vanguard of the infantry consisted of Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg’s crack Georgia brigade. Following Gregg’s brigade were Lawrence O’Bryan Branch’s North Carolinians and Archer’s mixed brigade.

Gregg’s South Carolinians engaged the green 16th Connecticut and the 4th Rhode Island as they moved through the Otto cornfield. The 4th Rhode Island reeled under volleys that slashed their left flank, forcing it to withdraw. With the regiments around it compelled to retire, the 16th Connecticut ultimately withdrew as well.

Following on Gregg’s heels, Branch’s Tarheels went into action on Gregg’s left flank. Branch ordered the 7th and 37th North Carolina, which formed the vanguard of his brigade, to advance at the double quick to intercept the 8th Connecticut. Caught in converging fire from Branch’s Tarheels and Confederate batteries posted along the Harpers Ferry Road, the 8th Connecticut’s losses began to pile up. Appelman ordered his men to retreat. He had lost 173 of his 350 men.

Branch’s Tarheels changed front to the right to engage the 23rd Ohio and 30th Ohio of Ewing’s brigade. The Buckeyes found themselves taking fire from Branch to their front and Archer and Gregg on their left flank, and they also withdrew.

During the confused fighting, Branch was reconnoitering for his brigade when he was struck in the head with a fatal bullet wound. His death came as a heavy blow to Lee’s army.

At 5:30 pm Fairchild, Welsh, and Christ, who stated that their commands were threatened by the fresh Confederate forces arriving to their south, withdrew toward Antietam Creek. The enlisted men of these three Federal brigades were furious at having to give up ground for which they had bled heavily. The drive on Sharpsburg had ended.

The Union army suffered a crisis of leadership at the army and corps level at Antietam that cost it the battle. McClellan had literally thousands of fresh troops near the Middle Bridge in the form of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s V Corps and Maj. Gen. William Franklin’s VI Corps, with approximately 10,000 and 12,000 troops, respectively, which he refused to send to assist Burnside in his late afternoon drive on Sharpsburg.

The battle ended in a tactical draw. To McClellan’s credit, though, he had turned back Lee’s invasion of the North. The battle cost the Union approximately 12,400 casualties, and the Confederacy approximately 10,300 casualties. The following night the Confederates withdrew south across the Potomac. They would invade the North again in less than a year’s time.

Join The Conversation

Comments