By Pat McTaggart

It was the third winter in Russia for the men of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein’s Army Group South, and things were going from bad to worse. Since the gigantic battle at Kursk in July 1943, von Manstein’s battered divisions had been steadily pushed to the west. In a massive counteroffensive after the battle, Soviet forces drove the Germans to the Dniepr River in the Ukraine with a series of shattering blows.

Pausing to regroup after reaching the eastern bank of the river, the commanders of four Red Army fronts waited anxiously to continue the offensive while streams of supplies and replacements filled their depleted ranks. In Moscow, Stalin and his high command (STAVKA) were planning a drive that would not only liberate the Ukraine, but reclaim the Crimea as well.

Even von Manstein would have approved the audacity of the operation. Spearheaded by armored divisions and motorized infantry, the Soviets planned a staggered attack by the four fronts, which would keep the Germans guessing as to where the main attack was taking place. After the German line was breached, regular infantry would surge through the gaps and hit any enemy units left in the main line from the rear. Taking a page from German armored doctrine, the Red Army tank units would keep going without worrying about their flanks until the Crimea was isolated. The following infantry and motorized units were to consolidate their gains, possibly encircling the three armies of Army Group South (1st and 4th Panzer and the 8th Army) in the process.

On paper, von Manstein had a powerful force with which to defend the Dniepr Line. In fact, many of his infantry divisions had an average combat strength of a thousand men. His panzer divisions were not in much better shape.

Von Manstein’s southern flank was protected by Col. Gen. Karl Hollidt’s 6th Army, consisting of 13 understrength divisions. The meandering Dniepr made it necessary for Hollidt’s divisions to defend the eastern side of the river in positions that had been hastily constructed and that were practically worthless in the face of overpowering Soviet superiority.

On October 1, the 3rd Ukrainian Front under Rodion Malinovsky began attacking German forces near Zaporozhye. While the Germans scrambled to send reinforcements to help, the 4th Ukrainian Front (Fyodor Tolbukhin) struck Hollidt on October 9. Supported by 400 batteries of artillery, Tolbukhin’s 45 infantry divisions, two guards mechanized corps, three tank corps, and two guards cavalry corps smashed through the almost useless defense works of the 6th Army.

The final blow came when the 1st and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts of Col. Gens. Nikolai Vatutin and Ivan Konev hit Army Group South on October 15. The Germans were slowly pushed back across the entire front of attack and were saved only by the rainy season, which began in mid-November. Casualties on both sides had been horrendous, and the Germans had little means of replacing their losses.

It was different for the Soviets. On their way westward, they immediately drafted any male of fighting age into their ranks. Few said no to the NKVD squads that roamed liberated areas on the prowl for new recruits. Taking advantage of the lull, Soviet commanders fleshed out their ranks, teaching the new soldiers the rudimentary basics of combat. At the same time, supplies poured into the battle area, bringing food and ammunition to continue the advance once the ground had sufficiently frozen.

Meanwhile, STAVKA revised its original plan, since annihilation of German forces on the entire southern front was no longer feasible. The bulge created in the October offensive, defended by General Erhard Raus’s 4th Panzer Army and the 8th Army under General Otto Wöhler, was tailor made for encirclement. Destruction of the two armies was assigned to Konev and Vatutin.

The Russians struck with with the onset of winter in early December. While Konev headed out toward the important communications hub of Kirovograd, Vatutin struck the 4th Panzer Army’s left flank and then headed for the Bug River. Both fronts were to link up on the Bug River at Pervoinaysk.

Blowing snow whipped by gale-force winds prevented either side from using air support, and the battle soon became hopelessly confused as marauding groups of Soviet tanks and mechanized infantry clashed with columns of German troops attempting to form a new line. Many of the German units soon found that they had been cut off and surrounded.

One of these units was commanded by 22-year-old Sergeant Franz Hofbauer. In a letter to the author, Hofbauer described those first harrowing days of the Soviet attack:

“I had barely taken over command of the 3/Fusilier Battalion 72 when the Russians attacked. Our company commander had been killed a few days earlier. By December 3, I realized that Ivan had us surrounded, so I formed the company into a Hedgehog [all around] defensive position. This was near the town of Cherkassy. We were attacked again and again by the Russians, but our position held long enough for the battalion to occupy a new defensive line.

“Our ammunition was almost nil, and I realized that the only thing that we could do is [sic] attack. We formed a wedge and struck Ivan in an area closest to our own main line. Luckily, the Russians were caught by surprise, and we were able to break through, taking our wounded and our weapons with us. I received the Ritterkreuz [Knight’s Cross] for this action, but it was the courage of my men that really saved us.”

The Soviet attack continued, with Vatutin creating more havoc with the 4th Panzer Army. Von Manstein tried to convey the seriousness of the situation to Hitler, but the German dictator would not listen, calling the field marshal a defeatist and threatening to relieve him. Seeing the writing on the wall, von Manstein decided to take matters into his own hands by reshuffling his forces. He handed over the 1st Panzer Army’s sector to Hollidt’s 6th Army and ordered it to Uman. There, the 1st Panzer Army would add to its ranks the XXIV Panzer Corps and the VII Army Corps of the 4th Panzer Army.

The commander of the 1st Panzer Army, the one-armed General Hans Hube, was also ordered to created a reserve armored force around the headquarters of the III Panzer Corps, which would soon be commanded by General Hermann Breith. The force included the 6th and 17th Panzer Divisions, the 16th Panzergrenadier Division, and the 101st Jâger Division.

The move was justified when on January 3, 1944, Soviet advance units were caught and mauled a mere 30 miles from Uman. As that engagement was taking place, Konev’s 2nd Ukrainian Front made a thrust toward Kirovograd. Led by Col. Gen. Pavel Rotmistrov’s 5th Guards Tank Army, the Soviets fought through the German defenses and encircled the four divisions now trapped inside the city.

Against Hitler’s orders, General Fritz Bayerlein led the four divisions in a successful breakout, giving von Manstein a new force to use against the Russians. They succeeded in stemming the Soviet advance, but the Red Army offensive had gained important ground and had created a dangerous bulge in the German line on the Dniepr bend. Von Manstein repeatedly called for the withdrawal of the units inside the bulge, but Hitler steadfastly refused.

Throughout January, the Soviets tried to keep their momentum going, but German counterattacks seemed to thwart them at every turn. In Moscow, STAVKA decided to shift the focus of the offensive and ordered Vatutin and Konev to concentrate on eliminating the Dniepr Bulge. With those orders, the two Soviet generals devised a plan similar to the double encirclement used so effectively at Stalingrad. The inner ring would be formed by infantry units supported by some tanks, while an outer ring, with the purpose of meeting enemy counterattacks, would be composed of mechanized and armored corps with infantry support. For the operation, the Soviets would enjoy an overall superiority of 7:1 in artillery, 5:1 in tanks and 2:1 in men.

Pressed into the bulge were General Theobald Lieb’s XLII Army Corps (5th SS Panzer Division “Wiking,” SS Brigade “Wallonien,” and the remnants of the 112th, 255th, and 332nd Infantry Divisions known as Corps Abteilung B) and General Wilhelm Stemmermann’s XI Army Corps (57th, 72nd, and remnants of the 389th Infantry Division). Joining them were the 88th Infantry Division and elements of the 167th, 168th, and 323rd Infantry Divisions, the 213th Sicherungs (Security) Division, and the 14th Panzer Division.

“We had no second or third line of defense, as was usual in the preceding years,” General Heinz Gaedke, who as a colonel had been Stemmermann’s chief-of-staff, wrote to the author.” But our corps was so depleted that our divisional commanders were happy that we even had a single line to occupy.”

The battle for the Cherkassy bulge began on January 24 with an attack by Konev’s 2nd Ukrainian Front against a 12-mile front that had no more than one German infantryman for every 15 yards. Penetrations in the German line were soon made, although it was not the knockout blow that the Soviets had expected.

STAVKA had hoped for a penetration of at least 30 kilometers on the first day, but steadfast German resistance upset the timetable. Interior communications and accurate artillery fire allowed German units to slowly retreat. Konev threw Maj. Gen. A.I. Ryzhov’s 4th Guards Army and Co.l Gen. Pavel Rotmistrov’s 5th Guards Tank Army into the fray, but only four kilometers were gained for a heavy price.

On January 26, the 1st Ukrainian Front attacked the border of the 88th and 198th Infantry Divisions. Supported by tanks, three and a half Red Army divisions smashed into the 198th, forcing it to retreat to the west. The 6th Tank Army under Col. Gen. A.G. Kravchenko exploited the gap, pushing the 88th to the northwest and breaking communications between the XLII Army Corps and the remainder of the 1st Panzer Army.

In the 2nd Ukrainian Front sector, Konev succeeded in expanding his previous gains, but an attack by the 14th and 11th Panzer Divisions almost succeeded in driving the Russians back. While the fighting continued, Rotmistrov, in a Guderian-style thrust, sent two tank corps (20th and 29th) on an end run. Disregarding his flanks, Rotmistrov pushed his armor westward to meet the 6th Tank Army. The outer ring of what would be called the Cherkassy Kessel (Cauldron) was almost complete.

The Germans in the Cherkassy bulge were in dire straits. The commander of the XLVI Panzer Corps, General Nikolaus von Vormann, recorded that Soviet tank and mechanized units sped past his panzers without stopping to give battle. Regardless of losses, the Russians were determined to bypass attacking German armor in order to close the ring around the Germans inside the bulge.

With Rotmistrov’s 5th Guards Tank Army moving from the south and Kravchenko’s 6th Tank Army advancing from the north, it was only a matter of time before the two met. Supported by infantry, Kravchenko’s 233rd Tank Brigade reached Lysyanka on the bank of the Gniloy Tikich River on January 27. The 233rd was followed by other units that crossed the river to form a bridgehead of 12 to 15 kilometers on the eastern side.

On January 28, the 233rd met with 5th Guards Tank Army units at Zvenigorodka, effectively sealing off the Dniepr bend. Both Konev and Vatutin continued to pour in more forces to strengthen the outer ring. German commanders inside the bulge pleaded for freedom of action, but no orders came. Bypassing regular channels, General Herbert Otto Gille, commander of the 5th SS Panzer Division “Wiking,” sent Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler a message reading, “In three hours, the encirclement of my division will be accomplished.”

Gille’s division was the strongest unit inside the Kessel. Its 15,000 troops were drawn from nations all over Europe and included Norwegians, Danes, Dutch, Flemish, Swiss, and Swedish volunteers. There were also Finns, Estonians, and Volksdeutsch (ethnic Germans) from most of the Eastern European countries. Gille had a total of 90 panzers and Sturmgeschütze (assault guns) at his disposal to fend off the Soviets. The armor would play a vital role in the coming days, as is evidenced by a letter to the author from 1st Lieutenant Willi Hein, a company commander in the 5th Panzer Regiment “Wiking”:

“On January 28 we attacked Olschana with four assault guns. The enemy had fortified the town, so we were attacking the high ground around it. We destroyed five enemy vehicles and lost one of our own.

“At 0600 on January 29 we attacked the village of Kirillovka with two assault guns, but strong enemy attacks north and east of Olschana forced us to retreat. Close combat took place after an enemy breakthrough.

“The following day Ivan took the high ground near our position with armor and supporting infantry. We had two assault guns left for a counterattack with an infantry company. Three enemy tanks were destroyed and 200 prisoners were taken before we were forced to retreat to our old positions.”

Other units were just as hard pressed. Captain Harry Schlingmann, commander of the 112th Pionier (engineer) Bn./Korps Abteilung B, wrote to the author, “(T)he constant action of the previous months had diminished our strength to that of a regular company. Once the Russians broke through our front line, we had to make due with little or no shelter in the freezing weather. Nevertheless, our orders were to attack the enemy whenever possible. We had no anti-tank guns so we used bundles of grenades and ‘sticky mines’ to destroy the Russian tanks.

“Our method was simple. We would huddle in our foxholes until the T-34s passed over us. Then, one group would fire at the following infantry while ‘killer teams’ would tackle the enemy tanks. We inflicted heavy losses on Ivan, but we lost many men ourselves. The enemy could replace his casualties, but we could not, so in the end, we were forced to retreat time and again.”

The Russian commanders in the field worked hard at consolidating their gains and in reinforcing the outer and inner rings of the encirclement. German forces inside the Kessel were fighting for their very existence as Soviet tank and infantry units pounded them. Elements of the 14th Panzer Division that were trapped inside the pocket battled the 18th Tank Corps, while the 389th and 57th Infantry Divisions began to fall back under the weight of savage Russian attacks.

Stemmermann, who had been given overall command of the Kessel, ordered his troops to fall back to shorten the main line of resistance. The retreat was covered by men like Sergeant Gerhard Fischer, an 18-year-old commander of a Sturmgeschütz (assault gun) in the “Wiking” Division, and Captain Fritz Steinbacher, a 30-year-old artillery commander in the 72nd Infantry Division.

Vatutin and Konev continued to push reinforcements into the battle. The outer line, which ran from Vinograd to Zvenigorodka, received the 53rd Army’s 49th Rifle Corps to help the 5th Tank Army keep the Germans from counterattacking. Other units arrived to help the 6th Tank Army hold the Germans at bay.

Supplying the Kessel fell to Luftwaffe transports that operated out of a forward airfield at Korsun. Although Soviet antiaircraft fire was heavy over the Russian line, the transports continued to fly ammunition and food to the surrounded Germans and pick up wounded for a harrowing flight to a field hospital outside the pocket. Oskar Hummel, a 22-year-old member of the “Wiking” Division, described his personal ordeal: “My right leg was shattered in a counterattack, and they [his comrades] saw to it that I was brought back. The whole platoon covered me so that I could make it to a field hospital. Ten men would rather have risked their lives than to leave one lying wounded. We knew that all Waffen SS soldiers were automatically shot by the Russians.”

Hummel’s ordeal was only just beginning. The field hospital came under attack and had to be abandoned, but Hummel was once again rescued by his unit. They loaded him on a horse-drawn cart and made for an airstrip, fighting their way through roving enemy patrols. Hummel sustained another wound during the journey and was finally put aboard an aircraft for the flight out. He survived the war, but lost his leg due to his wounds.

The Russians increased their efforts to wipe out key German defenses on January 31, when they launched combined arms attacks against the 88th Infantry Division near Boguslav and the Estonian “Narwa” Battalion of the “Wiking” Division. Neither unit gave much ground to the pummeling attacks.

One unit that had escaped most of the initial Soviet fury was the 2,000-man “Wallonien” Brigade, composed of Belgian volunteers under the command of Lt. Col. Lucien Lippert. In its ranks was the leader of Belgium’s pro-German Rexist Party, Captain Leon Degrelle. Rabidly anti-Communist, Degrelle had joined the German Army as a private. He rose through the ranks before transferring to the Waffen SS and had made a name for himself in several combat actions. In the coming days, the Belgians would be put to the test again and again as the battle for the Kessel intensified.

While the Germans fought to hold their perimeter, von Manstein moved to build a relief force with the III (General Hermann Breith) and XLVII Panzer Corps (General Nikolaus von Vormann). He planned a two-pronged attack, with the III Panzer Corps striking near Lysyanka and the XLVII Panzer Corps hitting the Russians south of Svenigorodka.

Schwere Panzer Regiment (heavy tank regiment) Bäke (Lt. Col. Franz Bäke) formed the nucleus of the III Panzer Corps. It consisted of 45 Tiger tanks and 45 to 50 Panthers augmented by two artillery battalions and a Panzergrenadier regiment. Additional tanks from elements of the 1st, 6th, 16th, and 17th Panzer Divisions brought its total armored strength to between 175 and 250. The Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH) SS Panzer Division was also ordered to move with all possible haste to reinforce the III Panzer Corps.

Von Vormann’s Panzer Corps was reforming, and most of its planned armored components were fighting in other areas of the front. Five panzer divisions (3rd, 11th, 13th, 14th, and 24th) were ordered to place themselves under von Vormann’s command, but von Manstein planned to use whatever forces that were on hand when the attack began since time was the critical factor.

The attack was planned to begin on February 3, and Stemmermann proceeded to shorten his line on his eastern flank in preparation for a possible breakout. His men had been fighting in blizzard conditions, with the average temperature hovering around zero degrees. On February 1, all that changed as a sudden thaw set in.

“The frost was 10-15 centimeters thick, but the thaw caused our heavy vehicles, such as tanks and artillery, to break through into the mire,” Sergeant Fischer wrote. “Thus, we were only able to pull back slowly, meter by agonizing meter.”

It was even tougher on the German infantry. Some tied their boots around their necks during the pullback to prevent them from being sucked off their feet by the clinging mud.

The fickle weather changed once again as it grew dark. Sub-zero temperatures returned, freezing vehicles and heavy equipment up to their axles in the Russian earth. German infantry and engineers used every means at their disposal, including pick axes, torches and even small amounts of explosives, to free the stricken vehicles in order to continue the withdrawal.

The pullback did not go unnoticed by the Soviets. Col. Gen. K.A. Koroteev, commander of the 52nd Army, ordered his infantry to attack, and a breach in the German line was made at Losovsk. A company under Captain Degrelle was ordered to retake the village, which it did after savage house to house fighting. As Degrelle reported his success, he received orders to pull out and report to brigade headquarters in Moshny.

Upon his arrival, Degrelle found himself in the midst of a new battle with Russian forces pressing hard to take the town. The Walloons were ordered to hold the sector while the rest of the “Wiking” Division pulled back farther to the west to form a new defensive line. After 10 hours of heavy fighting, they were told to abandon the town and make it back to the new line.

Meanwhile, von Manstein’s relief forces began arriving at their assembly areas. They were sent piecemeal to jump-off points, clawing their way through the mud. Von Manstein had to make changes in his plans on the spot because many of the units were having problems disengaging from their former positions. Also, his spearhead division, the 24th Panzer, was forced to turn around and head to the Nikopol sector because of Soviet attacks there.

Nevertheless, von Manstein ordered the relief attempt to start on schedule. Elements of the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions smashed into the 104th Rifle Corps, breaching the Soviet line. Shielded by units from the 134th and 198th Infantry Divisions and the LAH, the panzer divisions drove toward Veselyi Kut, a key crossing point on the Gniloy Tikich River.

Farther south, units from the 11th and 13th Panzer Divisions became bogged down in the mud after making initial progress against the Soviets in the Zvenigorodka sector. The 3rd Panzer Division was also forced to halt in the face of savage Russian counterattacks after taking the village of Kamunovka.

With the relief attempt underway, Stemmermann ordered his own forces into action. The 88th Infantry Division “Wiking” and Corps Abteilung B assaulted Soviet forces in Boguslav, but were thrown back with heavy losses. “We had heavy casualties,” a doctor in the “Wiking” Division wrote. “My dressing station was overflowing to the point that we had to use all available transport to get the unattended wounded to the main hospital.”

Russian countermoves made the relief attempt slow going as Vatutin ordered General S. I. Bogdanov’s 2nd Tank Army into the fray against the III Panzer Corps. Konev also shuffled his forces, sending the 5th Guards Mechanized Corps forward to stem the drive of the XLVII Panzer Corps.

The Russians also attempted to use propaganda to weaken the Germans. General Walter von Seydlitz, who had been captured at Stalingrad and was now working for the Soviets, wrote a letter to General Gille promising good treatment for his soldiers and an early release from captivity after the war.

Captain Schlingmann recalled, “the Seydlitz men (German POWs from the National Free Germany Committee, an anti-Hitler group) spoke to us through loudspeakers. They promised us everything a soldier dreams of if only we would surrender.

“We had been in constant combat and were freezing in our open trenches, so my men and I talked the situation over. We were very democratic about it. In the end, we decided that continuing the fight was the only solution—much preferable to dying in a Soviet labor camp—so there was no more thought of surrender.”

A short time later, Schlingmann was wounded in the thigh, his fifth wound of the war. His men took him to a hospital, where he was operated on in a room thoroughly riddled by artillery fire. Later, he was flown out of the Kessel for further treatment. He received the Ritterkreuz (Knights Cross) on February 14 for valor shown during the Cherkassy operation.

Things got worse inside the Kessel when mud forced both airfields used to land supplies to close down on February 5. Engineers immediately started building a new one on drier ground, but it would take four days to complete. The closures gave transport pilots a much needed rest. More than 40 of the aircraft had been shot down or lost through accidents from January 29 to February 4.

The relief effort was also in trouble because of the mud. The LAH was still struggling to get most of its elements into the combat zone to reinforce the struggling III Panzer Corps, its Panther unit bogged down in the morass. Roads and bridges were inadequate to handle the heavy tanks, and going overland was next to impossible. The same held true for most of von Vormann’s XLVII Panzer Corps.

Stemmermann requested freedom of action as the Soviets closed in from three sides, noting that the relief force was inadequate to the task assigned it. Hitler refused to give up the Dniepr bend at first, but as the Russian pressure mounted he finally gave his approval for a breakout on February 6, with the attempt to begin on the 10th.

Once again, the weather took a hand in events as a new thaw during the day made moving men and equipment to assembly areas inside the Kessel virtually impossible. Looking at the overall situation, Stemmermann was forced to radio a request for more time before a breakout could be attempted.

Outside the Kessel, Bäke’s panzers finally reached Veselyi Kut on February 8. There they were halted by extremely fierce Soviet resistance from the fortified east bank of the Gniloy Tikich, which made any thought of crossing the river obsolete. Bäke was ordered to pull back and assemble farther to the south, along with the bulk of the III Panzer Corps. So far, the relief attempt had caused thousands of casualties on both sides, and the toll on equipment was just as fearful. On February 9, the 17th Panzer reported that it had only four operational tanks, while the 16th Panzer reported 19. German maintenance units worked furiously to get damaged machines back in service for the ongoing battle.

Breith’s Panzer Corps was now reinforced with the bulk of the LAH and the 1st Panzer Division, which had finally arrived near Risino, bringing with it 75 to 80 tanks. The weather had turned cold again, freezing the ground and making it easier for the tanks to move across the battered landscape.

Frozen ground also helped Stemmermann in his attempt to shorten his line for the upcoming breakout. His heavy equipment once again was able to move, and he was able to take Colonel Hermann Hohn’s 72nd Infantry Division out of the line and put it in reserve. The 72nd was the second strongest division inside the Kessel, next to the “Wiking.” It would be the spearhead division when the breakout took place.

Among the men of the 72nd were 1st Lt. Matthias Roth and Captain Fritz Steinbacher. Roth had recently taken over command of the 105th Infantry Regiment’s II Battalion after its commander became a casualty, while Steinbacher was a battalion commander in the division’s artillery regiment. Roth’s battalion would be on the cutting edge of the breakout, supported by Steinbacher’s artillery.

Time now became critical. German infantry units had suffered heavy casualties as they fought off Soviet attacks on the flanks of the advancing panzers, and there was no way to replace those losses. The Russians were funneling more men and armor in to try and cut off the relief forces. If von Manstein waited to order Stemmermann to begin the breakout, the Russians would have time to attack and force the Germans out of striking range of the Kessel. The field marshal made his decision and ordered his corps commanders to attack on February 11. They were told that this was a “do or die” operation and that if it failed their trapped comrades inside the Kessel were doomed.

At 6:30 am on the 11th, German artillery blasted the Soviet lines and the Regiment Bäke and the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions rolled forward, annihilating Russian forward defenses. On their right flank, Colonel Richard Koll’s 1st Panzer Division widened the gap, while the left flank was covered by the LAH and the 198th Infantry Division.

Koll ordered a kampfgruppe (combat group) of his division to head straight for the Gniloy Tikich. The unit took the river town of Bushanka and sped across a bridge spanning the river, establishing a bridgehead on the eastern bank. Soviet counterattacks soon followed, and Russian control of the hills surrounding the bridgehead made further progress impossible.

Koll then ordered his men to drive south for a surprise attack on Lysyanka, which was taken late on the 11th. It was a Pyrrhic victory, however, as Soviet engineers blew up the bridge spanning the Gniloy Tikich just as Koll’s panzers reached it.

Vatutin and Konev were quick to react to the German threat. The 21st Rifle Corps (4th Guards Army) was ordered into the Lysyanka sector, while the 5th Guards Cavalry Corps and elements of the 1st Guards, 5th Guards and 2nd Tank Armies were also moved to the area. Marshal Georgi Zhukov now assumed command of the Soviets’ outer ring, while Konev was placed in charge of the inner ring.

On the 12th, Soviet forces pushed the LAH out of Repki and then headed toward Votylevka, where they were stopped by other elements of the division. The LAH was also involved in a battle near Vinograd, where the Russians had broken through the lines of the 198th. A fierce battle ensued in which the Soviets were finally encircled and destroyed.

Sunday, February 13, gave the Germans a present. An enterprising Panther commander of the 1st Panzer Division, Sergeant Hans Strippel, discovered a ford that crossed the 30-meter-wide Gniloy Tikich. He ordered his driver to cross and was soon followed by other tanks from his platoon. Tanks from the 5th Guards Tank Corps opened fire on Strippel and his men, but the Panthers soon reduced them to smoking hulks. Two more Panther companies followed, accompanied by elements from the 113th Panzergrenadier Regiment.

Moving along the riverbank, Strippel found an intact bridge guarded by two T-34s. After making his 59th and 60th tank kills, he informed his headquarters that the bridge was in friendly hands and that it was strong enough to support armor. Reinforcements were immediately rushed to the area, giving the 1st Panzer a link between the two riverbanks.

The bridgehead on the east bank of the Gniloy Tikich was tenuous at best. Only a few elements of Regiment Bäke and the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions could be spared as reinforcements because those units were themselves engaged in heavy fighting around the villages of Chishinzy, Dzhurshenzy, and Daschukovka.

The final obstacle between the relief forces and the Kessel was Hill 239, midway between Dzhurshenzy and Potschapinzy. Although the 1st Panzer had only 10 operational tanks and two battalions of infantry in the bridgehead, an attack was ordered to take the hill on February 14. The assault took the village of Oktybar but was stopped dead in its tracks before Hill 239 could be reached.

Elements of the 5th Guards Tank Corps counterattacked during the next two days as tanks from the LAH, 16th Panzer, and Regiment Bäke joined the fray. The fighting was fierce as both armies fought at near point-blank range. Strippel and his platoon of seven Panthers accounted for another 27 Soviet tanks, but it soon became clear that the III Panzer Corps could go no further. The fate of the men inside the Kessel was now in their own hands.

Fighting was also raging inside the Kessel itself as the relief forces struggled forward. Stemmermann had been ordered to shorten his lines and move toward Schenderovka to assemble for the breakout. He had the “Wiking” and “Wallonien” abandon their positions at Gorodishche, while the 88th pulled out of Yankova.

“The plan for the breakout was designed by the 8th Army,” Gaedke wrote. “We naturally had to carry them out. Radio contact between the Kesseltruppe and the relief forces were constant, so we knew approximately where they were located.”

Under intense artillery fire, the Germans trudged through the mud and snow protected by the few remaining tanks and assault guns left inside the pocket. Units formed into assault groups around the Korsun area and final orders were given for the breakout. The first order of business was securing the villages of Schenderovka, Novo Buda, Kamarovka, and Khilki.

First Lieutenant Roth moved his men into position to attack the Russians on the night of February 11. A Soviet sentry noticed the gray shapes moving forward and raised the alarm as Roth’s men reached the Soviet lines. Roused from their sleep, the Russian troops valiantly tried to defend themselves, but Roth’s troops were already in the enemy trenches, slashing out with bayonets and entrenching tools as the Soviets poured from their night quarters. The savage fight lasted for an hour and a half, but the Germans took the line and went ahead to secure Novo Buda.

At Schenderovka, the “Germania” Regiment of the “Wiking” took the village by storm. Soviet forces immediately formed for a counterattack, and the SS troopers dug in, fighting off several enemy assaults. The fighting for the village continued on the 12th with the Germans holding firm.

On the 12th, Lippert’s “Wallonien” relieved Roth at Novo Buda, leaving his battalion free to continue the attack. Roth led his men against Komarovka, supported by Captain Steinbacher’s artillery. His men closed on the well-defended village, and fierce fighting erupted. On the 13th, the village was finally secured.

“Ivan fought like the devil,” Roth wrote to the author. “We used every trick that we knew to take the village. When it was over, we had killed about 90 enemy soldiers and had captured 50 more. We also destroyed eight tanks, seven mortars, and three antiaircraft guns.”

Stemmermann followed the action closely. He abandoned Korsun on the 13th, but was forced to leave his severely wounded cases behind in the main hospital. “The wounded, there were more than 2,000 of them, were left behind in the hospital with a volunteer doctor,” Gaedke wrote. “We hoped that the Russians would treat them properly. However, no one ever found out what happened to them once they fell into enemy hands.”

Throughout the 14th, the “Wallonien” was hit by several Russian attacks. Red Army artillery blasted away at the defenders of Novo Buda, and combined armor-infantry attacks pushed their way inside the village. The Walloons fought like tigers, destroying several Soviet tanks and finally pushing the Russians out of the village.

Lippert fell, mortally wounded in the head. Captain Degrelle took command of the brigade, which had already lost more than 200 men. For the next two days, the Walloons continued to hold the village against overwhelming odds.

Meanwhile, the 72nd Infantry Division was fighting two actions—one defensive and one offensive. In Komarovka, the 124th Infantry Regiment was engaged in a heavy defensive struggle against Soviet armor and infantry. Lieutenant Roth, commanding the lead battalion of Major Robert Kaestner’s 105th Infantry Regiment, assaulted Khilki supported by Steinbacher’s artillery. After a fierce struggle, the village was finally taken.

Outside the Kessel, the battle for Hill 239 was still in full swing. The III Panzer Corps attacked the position again and again, but Rotmistrov’s men held. Late on the 15th, a message was sent to Stemmermann stating “Capacity for action of III Panzer Corps limited. Group Stemmermann must perform breakthrough as far as Dzhurshenzy/Hill 239 by its own effort. There, link up with III Panzer Corps.”

No mention was made of the German failure to take the heavily defended hill. Therefore, Stemmermann and his men were set to unknowingly clash with a heavy concentration of Soviet troops in their desperate bid to escape. Thousands of German soldiers would die because of this miscommunication.

The breakout was set to begin at midnight on February 16. By now, the Kessel had shrunk to a five-by-seven-kilometer area, with Soviet artillery pounding all German positions. Stemmermann ordered an attack on three separate approaches. The 72nd would form the center of the attack, while Corps Abteilung B attacked on its left and “Wiking” on its right. When the main attack forces penetrated the Soviet line, the wounded and remnants of other decimated divisions would follow. The 57th and 88th Infantry Divisions formed the rear guard to hold off Russian forces attacking from the east.

Advance forces moved out in the bitterly cold night, unaware of what lay in front of them. The III Panzer Corps had finally realized its communication error, but attempts to inform Stemmermann failed because he had already ordered the destruction of his long- range radio equipment.

“There was no communication with the relief forces once the breakout began,” Gaedke wrote. “We did, however, know that the Oktybar area had been heavily fortified, so we went south of the village, where the Russian lines were supposedly weaker.”

Once again, Lieutenant Roth’s unit formed the spearhead for the 72nd. He was ordered by Kaestner to take Soviet outposts by bayonet in order to maintain secrecy. After silencing Soviet forward positions, it took Roth’s men more than four hours to reach Hill 239, which was assumed to be in friendly hands. Approaching the hill, Roth could see the silhouettes of enemy T-34s on the hilltop. He immediately informed Kaestner of his find.

Roth then moved his battalion around the northern edge of the hill and made contact with a Soviet trench line. With sharpened entrenching tools, bayonets, knives, and rifle butts, the Germans overwhelmed the enemy and burst through the Soviet line, followed by the rest of Kaestner’s regiment.

Other units tried to follow, but the Russians had been alerted and moved heavy reinforcements to close the gap. Heavy fire ripped through the German columns as commanders looked for alternate escape routes through the now heavily defended Soviet line.

Kaestner’s regiment continued forward and eventually ran into advance units from the III Panzer Corps. The regiment had finally made it, but the price of freedom was staggering. Three weeks earlier, the 105th had a strength of 27 officers and 1,082 men. When a muster was taken on the 17th, only three officers and 216 men reported.

The Russians were now fully alerted, and pure chance dictated which German units would make it through relatively unscathed, and which would be decimated trying to escape. Most of the 72nd Infantry Division took a southerly route around Hill 239. It sustained heavy casualties, not only from fire from that hill, but from Hill 222, which lay south of the escape route.

Corps Abteilung B made some initial penetrations, and several regiment-sized groups made it through before the Russians could fully mobilize. Those that followed were forced to run a gauntlet of fire to make it to safety.

“Wiking” ran headlong into the heavily entrenched Soviets. Its badly understrength Panzer Abteilung was engaged in heavy combat around Novo Buda and Schenderovka, supporting the 57th and 88th Divisions in an effort to stem advancing Russian forces coming from the east. Degrelle’s Walloons were also fighting for their lives against the advancing Soviets.

When dawn broke, the temperature stood at about 20 degrees fahrenheit, with blizzard conditions hampering both sides. In some areas, it was impossible to tell friend from foe in the blinding snow, and running gun battles sometimes erupted between friendly forces as the breakout attempt continued.

General Lieb had been placed in charge of the assault forces, with Stemmermann commanding the overall operation. With more Soviet reinforcements arriving, the follow-up German forces were pushed steadily southward toward the Gniloy Tikich. Lieb drove his men forward unaware that Stemmermann had already fallen victim to Russian fire.

His chief of staff, Gaedke, described the general’s death to the author: “Stemmermann, leading the rear guard, wanted to fight his way out on foot. However, his strength soon gave out. We halted a horse-drawn cart, and the general climbed aboard. A short time later, an antitank shell hit the cart, blowing it to pieces and killing everyone on it.”

Lieb and his staff finally reached the Gniloy Tikich around midday on the 17th. Lieb was greeted by a sight of pure chaos. Literally thousands of German troops were stranded on the bank of the river while Soviet artillery blasted the area. The screams of the wounded filled the air, and the dead lay everywhere.

The river was more than two meters deep and was several meters wide with a very strong current. Ice flows sailed by on the water as the men desperately looked for an avenue of escape. Pure bad luck had led the Germans to this section of the river. About two kilometers upstream, the 1st Panzer Division had built two temporary bridges, but Soviet blocking forces were now between the trapped Germans and the way to safety. The bridges might as well have been on the moon.

When the “Wiking” arrived on the scene, General Gille ordered his remaining vehicles to be driven into the river, hoping to form a makeshift bridge. Most of them were swept away in the strong current, as were the human chains of swimmers and nonswimmers attempting to cross. Some men used everything from tree limbs to vehicle doors to try and make it across.

At that point, Russian tanks were spotted coming from the east. The last panzers left in the Kessel rushed to engage them as panicked German solders stripped off their uniforms and ran into the freezing river. Some of the better swimmers took non-swimmers with them, returning again and again to bring other comrades across.

The German tanks were soon destroyed, and all hell broke loose as the Russian T-34s advanced on the eastern bank. Firing at point blank range, the Soviet tanks roamed at will, crushing those that could not escape their treads and blasting huge gaps in the vast crowd of Germans. The river was soon filled with thousands of naked or half-naked men, all trying to make it to the western bank.

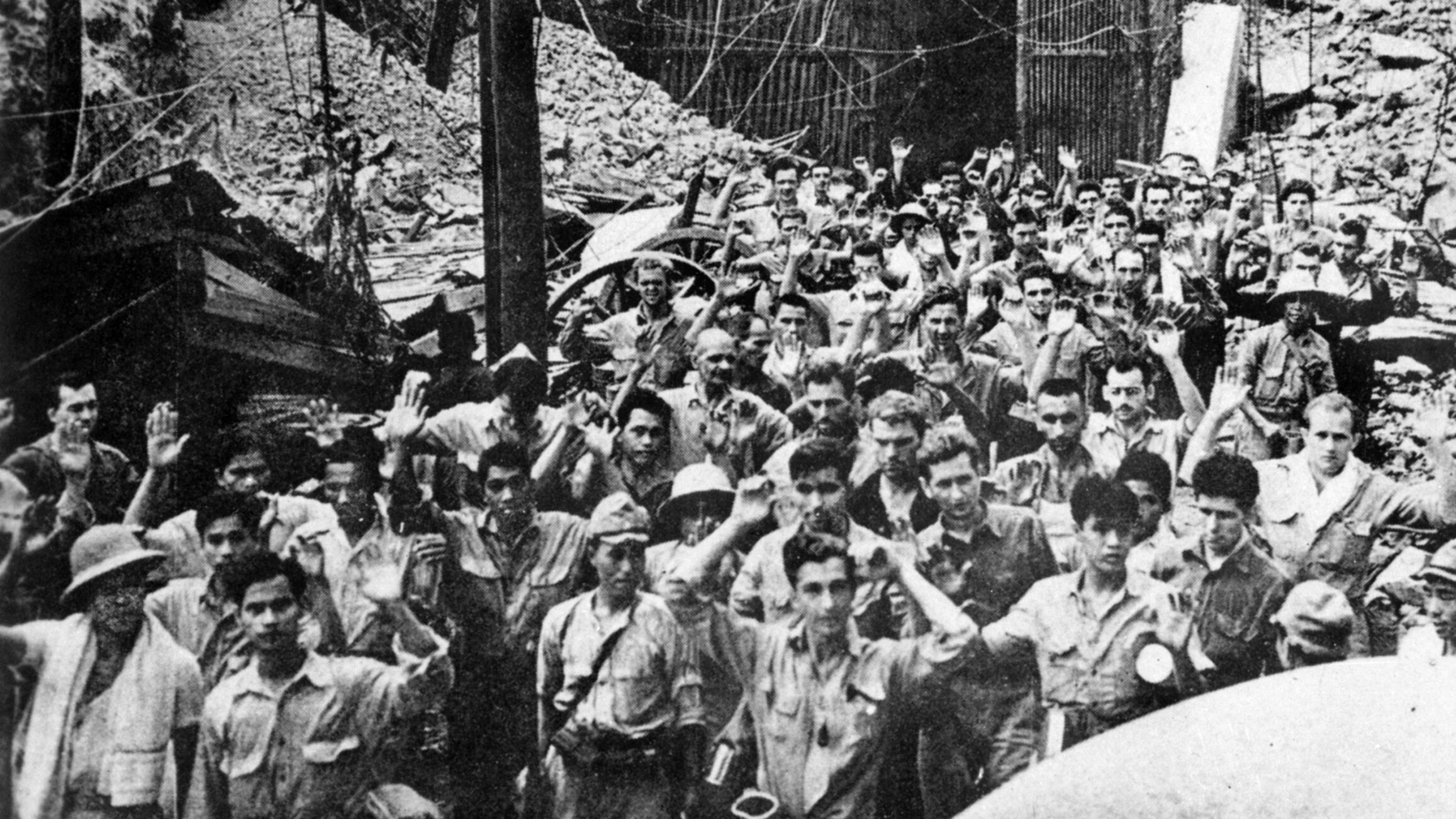

At Lysyanka, the initial trickle of survivors alerted the 1st Panzer Division about the inferno taking place just a few kilometers away. Engineers were rushed to the scene, where they began building temporary bridges under heavy Russian tank and artillery fire. More men struggled across, and by nightfall only German corpses remained on the eastern shore. Up to 35,000 German troops had escaped the Kessel, but nearly all heavy weapons and equipment had been lost, and two German Corps had been more or less destroyed.

Only 4,000 men remained alive in the “Wiking,” and the “Wallonien” Brigade, whose men had brought the body of their dead commander with them, was down to 632. Several of the other divisions engaged in the Kessel were disbanded soon after.

Sergeant Fischer, the 18-year-old Strumgeschütz commander, received the Knights Cross for his actions at Cherkassy, as did Lieutenant Roth and Captain Steinbacher. In a 1989 letter to the author, Fischer summed up his feelings about the battle: “The military commanders saw it as an excellent operation—35,000 men escaped! However, the soldiers who were there regarded it as a sad, bestial massacre.”

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front and the author of the book Siege! Six Epic Eastern Front Assaults of World War II. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.