By Charles Hilbert

The Ottoman Empire of Sultan Abd al-Majid I was in decline. Less than 200 years before, it had reached its high water mark in 1683 when Ottoman armies surrounded the walls of Vienna, only to be beaten back by the forces of Jan Sobieski, King of Poland, and Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor, who were bankrolled by Pope Innocent XI and the Holy League. It was the turn of the tide for the Ottomans: by the end of the war, 16 years later, they had lost Hungary and Transylvania. More losses were to follow.

Over the course of the next century, the Hapsburgs and Empress Catherine the Great of Russia pushed the Ottomans out of the Balkans, nearly to the gates of Constantinople. With the assistance of Britain, France, and Russia, the Greeks won their independence in 1832. This was shortly followed by the revolt of Muhammad Ali, governor of Egypt, and his son Ibrahim Pasha. The revolt forced the sultan, whose father Mahmud II had, after repeated rebellions of the Janissaries, destroyed those elite troops, to ask for assistance from his former enemies, Britain and Czar Nicolas I of Russia. With their aid, Ibrahim Pasha was confined to Egypt, where Abd al-Majid then ruled in name only.

The obvious military weakness and political instability of the Ottoman Empire prompted the czar to liken the empire to a dying man, the disposition of whose possessions arrangements would soon have to be made. When the empire went to pieces, the czar wanted to be there to pick some of them up, especially any part that could fulfill the dream of every Russian potentate: a warm-water, all-weather port with access to the Mediterranean Sea, in this case, Constantinople or, as it came to be called, Istanbul.

Of course, the French did not like the idea of Russian ships sailing around the Mediterranean and possibly interfering with their North African trade, and the British were not thrilled at the thought of Russians in Turkey, which would put them a little too close to India, where they might interfere with Britain’s lucrative subcontinental exploitation. Like a gathering of vultures, the great powers of Europe were poised to go to war over the spoils of the moribund Turkish Empire. They just needed a catalyst to set things off, and a few bellicose monks in Palestine would provide it.

Sacred ground for the three great monotheistic religions, Jerusalem in the mid-19th century was still under Ottoman control. Some 10 kilometers south, in Bethlehem, the Church of the Nativity was supposed to have been built over the manger where Jesus Christ was born. Turkish soldiers outside the building provided security for pilgrims visiting the church. Inside was another matter. Roman Catholic monks were supposed to share the church with their Greek Orthodox opposites, but the Greeks had the key to the front door, and in 1847 they removed a star that had been placed by the Catholics over the spot that they supposed had once been occupied by Jesus’ manger. The subsequent argument regarding the return of the star led to blows with candlestick and crucifix. By 1852, the Catholics had managed to get their hands on the keys to the front door, and they replaced the star, not without violent objection from some Orthodox monks, several of whom were killed.

The Greek Orthodox Church turned to Czar Nicolas for support and gave him the opportunity for which he had been waiting. In early March 1853, he sent Prince Aleksandr Sergeyevich Menschikov to demand that the keys be returned and that the czar be made protector of all Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. Menschikov was a wise choice if the czar meant to provoke war. The prince hated the Turks: at the siege of Varna in 1828, during the Russo-Turkish war, he had received a particularly painful and life-altering wound to his genitals. By the end of May, Menshikov had achieved nothing diplomatically beyond subtly insulting the Turks at every opportunity and getting the keys back. He gave the Turks eight days to proclaim Nicolas I protector of the sultan’s 12 million Orthodox subjects or face a Russian invasion of Moldavia and Wallachia.

On June 8, a British fleet steamed toward the Dardanelles. On July 3, the Russians crossed into Moldavia and Wallachia. In August, British and French diplomats convinced the czar to soften his demands, but this time the sultan, who expected the British to back him as they had aided his father in the nominal retention of Egypt, issued his own ultimatum on October 4, giving the Russians two weeks to withdraw from Moldavia and Wallachia. They did not, and the Turks crossed the Danube on October 28. Two days later, the British fleet entered the Bosphorus. Three days after that, during fierce fighting in which both sides routinely bayoneted enemy wounded, the Turks, under Omar Pasha, captured the town of Oltenitza as a prelude to cutting the Russian line of communication by taking Belgrade. However, expecting Russian reinforcements to arrive at any time, Omar Pasha abandoned his attempt on Belgrade and withdrew across the Danube by November 15. He was then put in charge of a convoy of ships taking supplies to the Ottoman army, which held the upper hand in Georgia.

Admiral Pavel Nakhimov was ordered to cut the Ottoman lines of communication and supply. He came upon the Turkish fleet as it entered the harbor at Sinope on November 23. Reinforced on November 30, he attacked. The Russian guns outranged the those of the Turks, and their exploding shells ripped Omar Pasha’s fleet to splinters. As the Russian ships moved closer, they changed to grapeshot: like giant shotgun shells, antipersonnel weapons that delivered multiple projectiles tore through the Turkish sailors. Only one Turkish steamship survived and made it to Constantinople.

The czar was happy, but the British and French were not. The British press called it a massacre, but the British government made no overt moves. The Turks were actually winning the ground war, and the British and French fleets, even more modern than the Russian, had nothing to fear from Nakhimov. In early January 1854, the Allied fleet entered the Black Sea. By the end of February, British public opinion, as well as government policy, led to an ultimatum ordering the czar to vacate Moldavia and Wallachia. In the event of what might now have seemed inevitable war, the British and French high commands targeted Sevastopol, the base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, for destruction.

Although no formal declaration of war against Russia was announced by Britain and France until March 28, 1854, both nations already had troop ships sailing east. On their way to Varna on the Black Sea coast of what is now Bulgaria, a site chosen for its equal proximity to Istanbul and Sevastopol, the French and British stopped at Gallipoli on April 5. It was here that the uniquely accoutered Highlanders met and became fast friends with their equally flamboyant comrades-in-arms, the French Zouaves.

Dressed in short blue jackets, baggy red trousers, a blue sash, white leggings, and a white turbaned red fez, they were the cultural and martial descendants of the Zouaoua, a North African tribe that had first fought for the French in 1830. By 1854, after reorganization by Napoleon III, the ranks of the Zouaves were composed of Frenchmen and divided into three regiments.

In command of Britain’s 26,000 men was 65-year-old FitzRoy James Henry Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan. He had a long military career that stretched back to the Peninsular War. In that conflict, he initially served as an aide-de-camp for Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. He had been wounded at the Battle of Bussaco in 1810 and was then appointed Wellington’s secretary, which did not stop him from being first into the breach at Badajoz in 1812. He was with the Iron Duke at Waterloo, where a musket ball smashed his right arm. Following the amputation of this limb, he calmly asked for it back so that he could remove a ring that his wife had given him.

Somerset continued his military career in administrative posts but would, more than once in the coming struggle, demonstrate a cool disregard for enemy fire. The British Army organization was indeed hopelessly confused, which led to problems in supply and medical treatment, but there was no braver man in the British Army than Somerset, who, although he might perhaps have lacked the all-encompassing, unique military genius of his former commander, cannot be blamed for the failures of either the commissariat or medical department.

The French were commanded by 53-year-old Armand-Jacques Leroy de Saint-Arnaud, Marshal of France. Before fighting in Algeria as a captain in the French Foreign Legion, Arnaud had been a mercenary, a fencing instructor, actor, singer, and violinist. Unlike his British counterpart, he had commanded an expeditionary force before, but by the time he was appointed to lead the French contingent against the Russians he was already dying of stomach cancer. Neither he nor Raglan would leave the Crimea alive.

On May 28 the Allies sailed for Varna, where both armies spent the summer subject to the ravages of cholera. By August 2, after several reverses in June and July, and with the Austrians mobilizing, the Russians had withdrawn from Moldavia and Wallachia. Allied demands had now been met, but Britain and France were taking no chances. What was to stop the Russians from renewing hostilities once the Allies had sailed back to Western Europe? Only the complete destruction of the Russian Black Sea fleet and the capture of Sevastopol could guarantee the safety of Istanbul and, incidentally, end the czar’s ambition to be a naval power in the Mediterranean and in the Black Sea too, which from the point of view of British and French politicians would not be an undesirable consequence.

One month after the Russian withdrawal, the Allies sailed for the Crimea. Two weeks later, on September 14, they landed at Calamita Bay, 35 miles north of their intended target. Five days after that, under the watchful eyes of some ragged Cossacks, they began marching south, the British inland on the left and the French close to the sea on the army’s right. They had already lost 7,000 men to cholera.

At the Bulganak River, the British skirmished with the Russians. But Menshikov had already decided to fight at the next river crossing. Drawn up on the heights south of the Alma River behind fortified positions, 35,000 Russian infantry, cavalry, and artillery awaited 60,000 British and French troops. Menshikov expected to hold the line of the Alma for at least three weeks.

On September 20, the guns of the fleet cleared the Russians from the high ground on their left as General Pierre Bosquet led the 2nd Division of Zouaves charging uphill, prompting St. Arnaud to remark, “My soldiers run; [the British] walk.” But, as the French center, the 1st Division under Marshal François Canrobert, and left, the 3rd Division, under Prince Napoleon, cousin of the emperor, bogged down, the British did walk in two lines down the slopes to the Alma, through tangling vineyards, across the Alma, and up the opposite slopes toward the Russian redoubts, constantly under fire of round shot, exploding shells, and musket balls. It was there that the superiority of Allied firepower became apparent to both sides. The Russians, advancing in columns, 32 men across and 25 deep, were armed with smoothbore muskets and trained to use the bayonet. The British and French were equipped with rifles firing the conical minie bullet, 10 times as accurate as the Russian muskets.

About 21/2 hours after the battle began, Raglan led his staff forward for a better view of the proceedings. They rode past French skirmishers to their right and stopped on a little hill in the no-man’s land between the two armies. As projectiles of all kinds whipped past them, Raglan, looking to his left, noticed Russian artillery firing on the advancing British lines. “Now, if only we had a couple of guns here,” he said. Ordering up some artillery, he enfiladed the Russian guns and forced them to withdraw. His first line had been repulsed from the Russian redoubts, but, with the Russian guns withdrawn, the second line, including the Highland Brigade, recaptured them, and Menshikov was forced to withdraw. The battle had lasted 90 minutes. Three days later, the Allies were on the march toward Sevastopol.

Built on the southwestern tip of the Crimean Peninsula, Sevastopol is divided by two great harbors, the larger of which opens onto the Black Sea to the west and extends six or seven miles eastward into the hinterland, being about a half mile wide. About a mile or so east of the harbor mouth, jutting south for slightly over a mile, is what was then called the Man of War Harbor. This was aptly named: Vice Admirals Vladimir Alexeyevich Kornilov and Nakhimov, the latter who had destroyed the Turkish fleet at Sinope, had, after hearing the news of the Russian defeat at the Alma, sunk seven large ships to block the entrance of the main harbor, stationing their remaining battleships in the Man of War Harbor. From there, the Russians could fire in all directions onto any hostile forces approaching from the land.

It was Lt. Col. Eduard Ivanovich Totleben, a Russian engineer officer, who had suggested sinking the ships to block the harbor, and then, having taken their guns, he began to create a U-shaped defensive perimeter around the southern part of Sevastopol. A continuous line of entrenchments linked several large, protected artillery positions. These were dominated on the east by the Great Redan and to the north by the Malakoff, a giant defensive work, fronted by a semicircular tower of white stone that was 28 feet high, 30 feet in diameter, and five feet thick. Five heavy guns were mounted at the top of the tower. Behind the tower were numerous transverse walls and secondary fortifications. There were other smaller bastions placed along the defensive line, and these works were sited so that they could support each other with artillery fire. The northern half of Sevastopol was protected by an old star-shaped fort and mostly contained warehouses and more fortifications. It was, of course, separated from the southern part of the city by the main harbor.

Taking the northern suburb of Sevastopol under the fire of the fort’s 47 heavy guns would have been costly. It would have left the Allies with a half mile of water between them and the rest of the city south of the main harbor, and with their forces vulnerable to the guns of the Russian fleet stationed in the Man of War Harbor. They decided to march around the city and attack from the south. As the British and French marched south, Menshikov led his army out of the city heading east. Raglan, once again in front of his entire army, accompanied only by his staff, ran into the Russian rear guard. Ever bellicose, he ordered up some artillery and blasted the retreating Russians. His French counterpart, St. Arnaud, by then in the stages of advanced stomach cancer, appointed Canrobert commander of the French Army. Canrobert was a highly decorated combat veteran and had commanded a division of Zouaves at Alma, where he was wounded twice.

On September 26, the British took the harbor town of Balaklava, where they would land their supplies. The next day the French took Kamiesch to the west as their supply base. From these harbors the land rose to 3,000 feet and formed the Uplands, an eight-mile-square plateau devoid of trees. The British would hold the right of the U, the French the left. To the right of the British was the Tchernaya River, beyond which Menshikov awaited the opportunity for battle.

As the armies made camp, Lt. Gen. Sir George Cathcart, who also had fought with Wellington and later in South Africa, urged an immediate attack on the southern defenses of Sevastopol. Canrobert declined, preferring to institute a textbook siege. Afterward, the Russians admitted that an immediate assault would probably have carried the city. As it was, the British and French settled down and began digging trenches and hauling their artillery up the heights.

The French held the left of the siege lines, with both their flanks protected. The French left flank was protected by the sea and the French right flank by the British, whose own right overlooked the Tchernaya River, beyond which was the Russian Army. Mounting a siege in the 19th century followed prescribed guidelines. First, artillery batteries would be emplaced, then trenches would be dug parallel to the enemy fortifications. From the parallels, saps would be extended in a zigzag manner, and from the ends of the saps new parallels would be dug until they were close enough to the enemy for the besiegers to mount an attack. By that time, the artillery would have created a breach through which the attack would take place. With the siege begun, Arnaud sailed for Istanbul. He died en route on September 29, 1854.

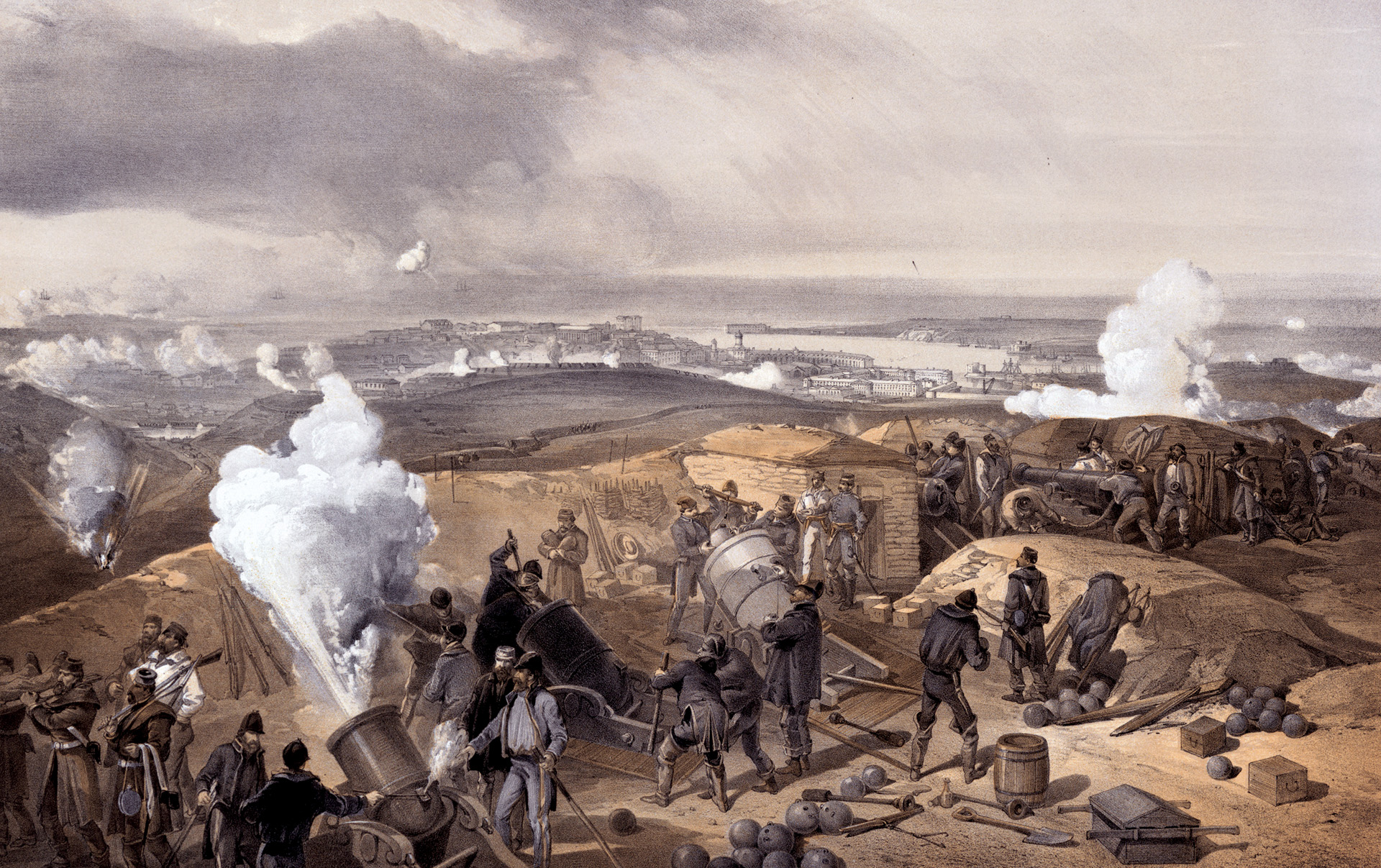

At 6:30 am on October 17, the English and French opened fire on the defenses of Sevastopol with 125 guns. The Russians replied with 172 guns, mostly manned by sailors from the fleet. Some of the British guns were also manned by men of the Naval Brigade. With so many explosions, all happening at the same time as a continuous roar from all types of artillery, Sevastopol was soon shrouded in smoke. A half hour after the commencement of the barrage, an errant wind sprang up and revealed the top of the Malakoff shot away.

At 9 am a Russian shell struck a French magazine, throwing debris and body parts into the air. The French fire slackened, and two hours later had stopped entirely. By 12:30 pm the French fleet had arrived and a half hour later was joined by the British fleet, which now exchanged fire with the Russian ships anchored in the Man of War Harbor. Although many Russian guns were destroyed in this savage artillery duel, the fire of the Russian batteries remained constant. Totleben had buried extra cannons near each emplacement; when a gun was destroyed, the surviving crews just dug up another one and manhandled it into place.

With the Malakoff destroyed and most of the guns in the Great Redan dismounted, the Allies had a good opportunity to assault the town. However, the French, with their artillery out of action, declined, fearing that enfilading fire would rip through their assault columns. As dusk fell, the firing lessened. The Russians had paid a heavy price, suffering 11,000 dead and wounded. Kornilov was among the killed, and Nakhimov was one of the wounded. A round shot had smashed the lower part of Kornilov’s body as he and Nakhimov observed the battle from the Malakoff.

During the night the Russians repaired their damaged fortifications. On October 18 the British again opened fire, while the French repaired their works. The following day, the French joined the British. That night, the Russians again replaced every damaged gun and repaired every emplacement. The Allies realized that the siege would not be over quickly.

While the Allied and Russian siege guns were battling it out, Menshikov had been reinforced. He realized that if he could cut the British off from their base at Balaklava they would either have to retake it, with the Sevastopol garrison threatening their rear, or they would have to march to the French base at Kamiesch and disembark. Either way, it was a good bet that cutting the British supply line would end the siege. On October 25, he attacked and initiated the famous Battle of Balaklava, during which a “thin red streak,” as reported by Times correspondent William Howard Russell, which would, years later, be metamorphosed into a “thin red line,” of Highlanders repelled the Russian cavalry. The British Heavy Brigade further discomforted their more numerous opponents, and the Light Brigade executed its immortal but tactically unsound charge into history.

On the next day, two Russian columns attempted to turn the undermanned British right flank. Charging out of the city through the ravines that cut their way through Mount Inkerman, they were held up by the bayonets of the British pickets and then shot to pieces by 18 guns firing grapeshot. This Battle of Little Inkerman convinced the British that their right was secure. It did not convince Menshikov.

On the morning of November 5, 35,000 Russians attacked the British right. In a confused series of small, desperate, hand-to-hand encounters, the battle lines swayed back and forth through the foggy canyons of Mount Inkerman. On the far right, at the head of his men, Cathcart was shot through the chest and fell dead from his horse. Things looked bad for the British when Bosquet led the Zouaves onto the field and drove back the Russians, accompanied by the beating of drums and the blaring of trumpets, which Raglan noted as “their infernal toot-tooting.” The British commander had earlier ordered two 18-pounders forward. They now reached their position and, firing round shot, forced the Russian artillery to withdraw. Canrobert arrived with more French reinforcements, and, after shredding the Russian columns with minie fire, they, with whatever British units were still operable, drove the Russians from the field. The Russians had lost 11,000 men, including six generals; the British lost 2,357 of all ranks and 15 generals. The French suffered 786 dead and wounded.

With the British force now reduced to 16,000 effectives, the French assumed control of the far right of the siege lines. They now held both flanks, with the British in the center. Menshikov, realizing that his men could make no headway against the hail of minie bullets, decided to let the winter weather do what his shattered columns could not. He did not have to wait long. On November 14, one of the worst hurricanes ever to strike the Black Sea demolished a good part of the British navy, sinking 21 ships and most of the army’s supplies.

Despite the efforts of Florence Nightingale, by the end of January 1855 more than 23,000 British soldiers had died or become too sick to report for duty. By springtime, the French, who were slightly better prepared for the cold, had lost more than 11,000 men. On January 17, the Russians attacked Eupatoria to the north of Sevastopol. They were slaughtered by the Turkish garrison. Czar Nicolas dismissed Menshikov. In February, the czar fell ill and died on March 2. He was succeeded by his son, Alexander II, who vowed to continue the fight.

By then, both sides had realized that the Malakoff was the key to Sevastopol. It lay before the French lines, with a small hill called the Mamelon 500 yards in front of it. Both sides decided to occupy this hill. The Russians got there first on February 22. The French assaulted the Mamelon that night but were driven back by heavy artillery fire from the Russian lines and the ships in the Man of War Harbor. To the left of the Mamelon, the Russians fortified another position known as the White Works.

By April 9 the Allies were ready to recommence the bombardment of Sevastopol. They did so with 501 guns and mortars. The Russians replied with 446 artillery pieces. The White Works were blown away by the French on the next day; the day after that they silenced the Mamelon. All the while, the Allies’ parallels and artillery platforms were inching closer to the Russian defenses. The French, having an easier time of it because of the nature of the soil, were able to narrow the distance more than the British. The artillery duel lasted for 10 days.

In mid-May, Canrobert, at odds with Napoleon III, resigned his command. His replacement was General Aimable Jean Jacques Pelissier. Pelissier had mercilessly slaughtered Arabs in Algeria, and he was not afraid to attack, no matter what the cost. His first targets were the Mamelon and the White Works. For two days, the French bombarded these positions. About 6 pm on June 7, three rockets rose from the French positions, signaling the assault. The Zouaves were among 5,000 troops who leaped out of their forward parallel and charged up the slopes of the Mamelon, through a hellfire of musket balls, round shot, grapeshot, and exploding shells. Ten minutes later, 500 Zouaves lay dead, but the tricolore drapeau now fluttered over the Mamelon.

The Zouaves did not stop there. They surged forward toward the Malakoff, but, having no orders to attack the position, they were not equipped with scaling ladders and so were stopped by the ditch that lay before it. From the Malakoff the Russians poured down a murderous fire that forced the Zouaves back to the Mamelon; another assault drove the French back to their trenches. Pelissier called up his reserves and sent 20,000 French soldiers over the top. They pushed the Russians back, and retaking the Mamelon, once again charged headlong at the Malakoff. As before, they were unable to cross the ditch and were forced to retreat to the Mamelon. This time there was no Russian counterattack, and the French Tricolor remained fixed on the hill of the Mamelon. While the seesaw battle for the Mamelon was going on, the French also captured the White Works. They paid for their success with more than 5,000 casualties.

The British took the Quarries, a fortified position that put them closer to their next objective: the Great Redan. This was a giant earthwork built in the form of a V, the apex pointing at the British lines. To get to the redan, the British would have to cross 400 yards of no-man’s land, somehow make their way through an abatis of tangled trees and branches four feet wide and five feet high, cross a ditch, and then charge 26 feet up the sides of the V, under fire from musket and cannon the entire way.

After a day-long bombardment on June 17, the guns of the Great Redan and Malakoff were silenced. The Russians worked through the night to remount them. Although a two-hour bombardment was planned to disable the remounted guns, Pelissier canceled it, and before dawn the next day, the French attacked. Crossing 160 yards under heavy fire, three French columns faltered. A handful of Zouaves made it to the Malakoff and crossed bayonets with the defenders, but they were too few to take the works and were forced back to their own trenches. As the sun rose, Raglan, observing the French attack from the Quarries, ordered an assault on the redan to draw the fire of the Russians and take some of the pressure off the French.

The British made it as far as the abatis, where they were shot to pieces by a storm of grapeshot and musket balls. They had to retreat under the same murderous fire. The French had lost 3,500 men, the British 1,500, and the Russians 5,500. As Raglan visited the wounded, one young officer accused him of being responsible for the slaughter. From this moment, Raglan’s health began to fail, and after suffering an attack of dysentery, he died on June 28, 1855. Pelissier, who had mercilessly massacred tribesmen in Algeria and had repeatedly sent his own men to their deaths, cried uncontrollably at Raglan’s bedside. Lt. Gen. James Simpson assumed command of the British forces.

Almost a month later, Nakhimov was visiting the Malakoff, looking through field glasses at the French positions about 250 yards away. He made light of the minie balls striking near him. He was hit above the left eye and died two days later on July 12. A month after that, the Russians under Menshikov’s replacement, Prince Mikhail Dmitrievich Gortchakoff, launched their last attack. They were driven back by the French and the newly arrived Sardinians with a loss of 8,000 men. On the next day, August 17, 775 Allied guns opened up on Sevastopol. For the Russians, it seemed to be the last straw. Gortchakoff decided to abandon the southern half of the city and construction was begun on a pontoon bridge across the main harbor. Although the bridge was finished by July 24, and refugees had begun to leave the city, Gortchakoff changed his mind and reinforced the outer defenses.

With the French trenches now about 25 yards from the Malakoff, a general assault was set for noon on September 8, exactly when the Russians would be changing garrisons at the Malakoff. To draw the Russian fire, the British would once again attempt to take the Great Redan, while the French assaulted other fortifications on both flanks. The final bombardment of Sevastopol began on September 5.

On the appointed day 1,500 cannons of various caliber roared in an endless duel of shot and shell, while French General Patrice MacMahon impatiently waited for Chef de Bataillon de Marcilly of the engineers to bring up scaling ladders for the assault on the Malakoff. General Barthelmy Lebrun, MacMahon’s chief of staff, after finding the ladder company hopelessly bogged down in trenches filled with assault troops, ordered them to come up as soon as possible, and then rejoined MacMahon in the forward parallel where the general stood oblivious to the bullets and bombs striking and bursting around him.

Ladders or no ladders, the attack was scheduled for noon, and at noon the 1st Zouaves would advance. Lebrun stood near MacMahon, holding out his watch as the hands slowly ticked toward 12 pm. Captain See of the Zouaves, commander of the forlorn hope, gripped a gabion, a giant wicker basket filled with earth, that formed part of the rampart of the trench, ready to propel himself over the top. The Allies’ artillery fire slackened, then stopped. Lebrun lowered the blade of his sword and announced: “Midi!” MacMahon, shouting “Forward! Long Live the Emperor,” attempted to lead the attack, but was held back by his aide, Major Borel, and Lebrun, who grabbed him by the coattails, advising him to wait at least until the Zouaves had crossed the ditch in front of the Malakoff.

The Zouaves leaped out of the forward parallel and charged across 25 yards of no-man’s land pitted with shell craters and raked by the fire of Russian cannons and muskets. In a desperate minute they reached the ditch, six to seven meters deep, but without scaling ladders. The Zouaves simply jumped into the ditch. From the forward parallel MacMahon watched his men disappear into the ditch. For a moment or two they were lost to sight, then the Zouaves, all trained in gymnastics and some equipped with pickaxes, began to crawl slowly up the rock escarpment of the tower of the Malakoff. MacMahon could no longer be restrained; the 47-year-old general climbed out of the trench and ran to join his men. Chef de Bataillon de Marcilly and the ladder company arrived just in time to stop him from jumping headlong into the ditch. Lowering their ladders and laying planks across them, the engineers made a bridge over the ditch, and the Zouaves poured across.

About 40 Zouaves had nearly reached the top of rampart when Russian infantry appeared and fired down on them. The colorful but deadly French troops reached the crest of the fortification and closed with their enemies in a hand-to-hand combat of bayonet and rifle butt, the Russian gunners clubbing Zouaves with their ramrods and knocking them into the ditch below. More Zouaves reached the top and the Russians gave way before their sharp bayonets, retreating to a transverse wall, part of the inner fortifications of the lozenge-shaped Malakoff. MacMahon arrived as the Russians withdrew. Ten minutes after they had left their trenches, the tricolor was hoisted above the Malakoff by a noncommissioned Zouave officer named Eugene Libaut. This was the signal for the British assault to begin. Unlike the French, their forward parallel was 200 yards away from their objective. As they advanced, they were subjected to heavy cannon and musket fire.

The tricolor had been standing for five minutes when a British officer arrived to ascertain the situation. MacMahon informed him, “Here I am, and here I stay.” As he spoke, the Zouaves were advancing along each flank of the inside of the works, clearing the Russians from their traverse defenses. The Russians fought back every step of the way, retreating from one traverse wall to the next. As they neared the narrow entrance, facing Sevastopol, they bunched up, and here the struggle became hand to hand with the bayonet. This lasted but a few minutes, and then the survivors of the garrison ran headlong for Sevastopol. The Russians then began shelling their lost fortification and the French began taking casualties. A shell brushed MacMahon’s head but left him unhurt.

About 400 Russians were still in the base of the tower firing on the French inside the works. Lebrun decided to smoke them out and, with this in mind, set fire to some gabions that covered the entrance to the tower. The Russians, prepared to fight it out to the last, were not prepared to burn to death and gave themselves up. Fearing that the flames might spread to one of the magazines, Lebrun ordered some engineers to throw earth on the fire and put it out. As they dug, theydiscovered four wires buried near the entrance to the tower and suspected that they were connected to mines, which the Russians would have detonated, blowing up the Malakoff and all inside. These were quickly cut. For the rest of the day until nightfall, the Russians counterattacked the Malakoff. Column after column was driven off by the fire of the French minie rifles.

The British attack on the Great Redan had failed. Having reached the abatis, they could go no farther and were once again forced to retreat. The French had failed to take their other objectives, but they now held the Malakoff, which all considered the key to Sevastopol. The British had sustained more than 2,000 casualties, the French more than 7,000, and the Russians had lost more than 12,000 men.

As darkness fell, the Russians fired Sevastopol. Explosions went off all night. By morning there were no Russian soldiers left in the southern part of the city. The ships in the Man of War Harbor had been scuttled; the bridge to the north side was blown up at dawn. The defense of Sevastopol had lasted 349 days. Allied troops entered the town on September 9 and began to loot whatever was left undamaged. “A stalwart Irish grenadier, when being rebuked for pilfering, answered: ‘Sure an,’ your ‘onor, them nice gentlemen they call Zouaves have been after emptying the place clane out,’ recalled Sergeant Timothy Gowing, Royal Fusiliers. ‘Troth, if the Divil would kindly go to sleep for only one minute them Zouaves would stale one of his horns, if it was only useful to keep his coffee in.’ They proved themselves all, during the fighting, troublesome customers to the enemy; and now that the fight was over they distinguished themselves by pilfering everything they could lay hands upon.”

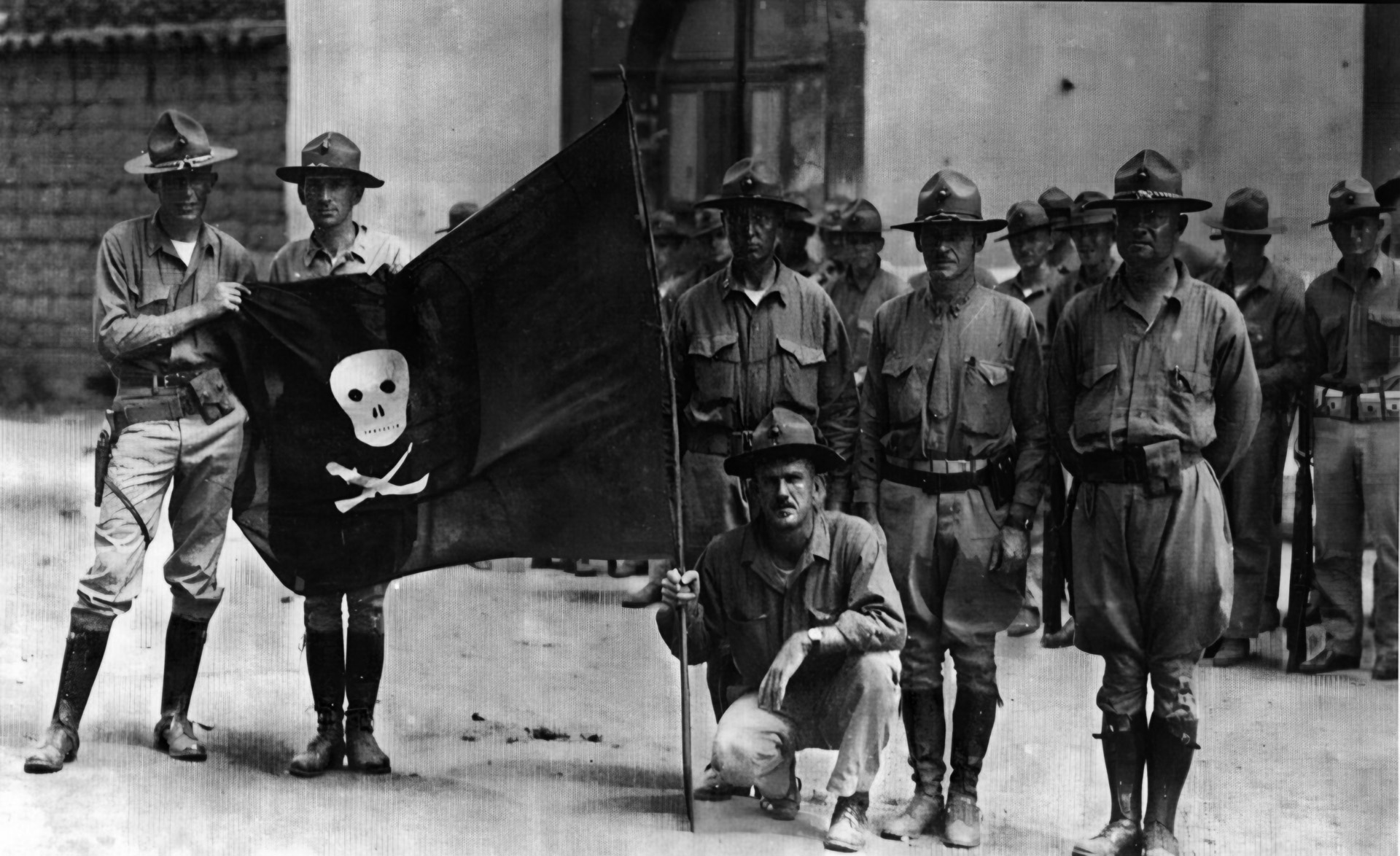

The Allies now held the southern half of Sevastopol and the Russians the northern suburbs. Apart from a few cannon balls fired across the harbor, the fighting was over, and both sides settled down for the winter. With Prussia pressuring the czar to accept the Allies’ peace terms, the Treaty of Paris was finally signed on March 30, 1856. Approximately 750,000 men had died, many as a result of disease. The Russian fleet never sailed the Mediterranean, and the Ottoman Empire gained a much needed respite from Russian expansion. As for the French Zouaves, their exploits, including their savage assaults against the Malakoff, inspired both sides in the American Civil War to raise regiments of similarly attired colorful troops.

“As for the French Zouaves, their exploits, including their savage assaults against the Malakoff, inspired both sides in the American Civil War to raise regiments of similarly attired colorful troops.”

Too bad Americans weren’t inspired to learn the lesson of how much slaughter could be caused by modern weapons, not to mention how disease could ravage an army more effectively than grapeshot.