By Simon Rees

The lieutenant had reached the end of his tether. It was time to cut this impudent American wagoner down to size with the flat of his sword. But as a lesson in British Army discipline it proved an abject failure; the frontiersman responded by smashing a well-aimed fist into the officer’s face, leaving him sprawled in the dirt. Welcome to the world of Daniel Morgan.

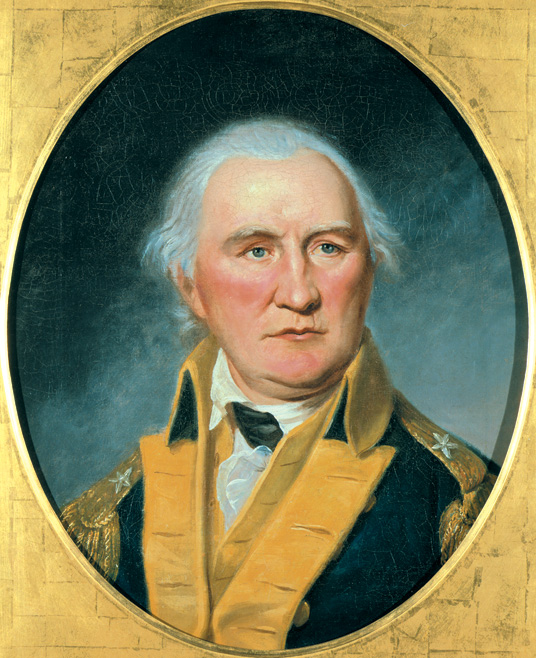

Born in New Jersey, in 1736, into the lower rungs of society, Morgan left home in 1753 after a domestic dispute with his father. He eventually ended up working as a wagoner in the frontier regions of Virginia. He was strong, muscular, and just over six feet tall. By 1755, he was under contract to transport supplies in Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock’s expedition against the French-held Fort Duquesne that culminated in the disaster of Monongahela. It was during this period that the altercation with the British lieutenant occurred, with Morgan sentenced to 500 lashes. He later claimed to have remained conscious throughout and even noted a miscount, with 499 and not 500 blows received. This is probably an embellishment, for striking an officer was a serious offense and the punishment would have been carried out with precision. White lie or not, the story would help cement closer ties with his men in the years to come.

Morgan quickly recovered and volunteered to serve with a company of Virginia rangers. On one occasion when delivering dispatches, he was ambushed by Native Americans. An enemy musket ball struck him below the jaw and exited through his left cheek, smashing both bone and teeth. Somehow Morgan remained in his saddle, spun his horse around, and bolted for safety before his enemies could follow up their surprise. His traveling companion was less fortunate, having been killed instantly.

By 1758, Morgan was working as a wagoner once more but often using his spare time to ill effect at a tavern near Winchester, Virginia, engaging in brawls and fist fights. He was also becoming a familiar face with the magistrates. However, by 1763, Abigail Curry was living with him and had helped calm his wilder side. The couple soon had two children, which prompted Morgan to focus on business and self-education. He thrived as a result and, by 1774, he had married Abigail, owned 225 acres of farmland, held 10 slaves, and had sub-leased his wagon. He was also captain of a local militia unit and involved in the colony of Virginia’s campaign against the Shawnee and Mingo in 1774, which was known as Lord Dunmore’s War.

A year later, the colonies finally took up arms against the British Crown. In building up the Continental Army, the Second Continental Congress requested that Virginia raise two rifle companies, one eventually selected to come from Frederick County, Virginia, which was Morgan’s home. With his status and military experience, the “Old Wagoner,” as he was sometimes called, was the obvious choice to lead the unit, and on July 15, 1775, he departed Winchester for Cambridge, Massachusetts, with 96 chosen men. From there they were sent to assist the rebel siege of nearby Boston.

Dressed in buckskins and armed with American long rifles, Morgan’s men were phenomenal shots for the age, frequently able to hit a seven-inch target at 250 yards. The long rifle achieved much of its effectiveness through the use of grooved barreling that added spin to a bullet. But it came with two important caveats: it took longer to reload than the smoothbore musket, and it needed a pair of skilled hands to achieve the best results.

Not long after joining the siege of Boston, Morgan’s unit was selected for another mission. The unit would join two Pennsylvania-raised rifle companies under the command of Colonel Benedict Arnold, who had planned an audacious attack on Quebec City via the Maine wilderness. Arnold’s expedition eventually totalled 1,050 men and was undertaken in tandem with Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery’s advance on Montreal.

The expedition departed Fort Western, Maine, on September 25. Morgan was in charge of the vanguard, whose main job was to clear the way ahead, a task that became a fearsome endurance test as the men struggled each day to portage their boats across unforgiving terrain. By mid-October the weather had turned foul, while supplies were running dangerously low and dysentery was becoming increasingly rife. Worse news came when Lt. Col. Roger Enos’s unit elected to withdraw. Arnold’s army then entered an icy, waterlogged hell between the Kennebec and Chaudière Rivers, with several men dying from exposure and many others, now starving, reduced to making broths with belt or shoe leather. Mercifully, the expedition left the wilderness and reached Quebec’s Sartigan region by November 3. Only about 650 men were left, while Quebec City’s garrison would soon reach 1,200 men.

The bulk of Arnold’s forces had successfully crossed the St Lawrence River and arrived within Quebec City’s environs by mid-November. Morgan now argued for an immediate coup de main but was voted down at a council of war. Instead, the Americans withdrew just upstream from Quebec City, where they continued to recuperate and waited for Montgomery, who was wrapping up his slow but successful Montreal campaign. He arrived on December 2, bringing an extra 300 men and some artillery pieces. Montgomery and Arnold now decided to wait for a snowstorm that they could use as cover to make a surprise assault on the city using two attack columns.

The storm finally arrived on December 30, raging in full fury by the early hours of December 31. Operations started at 4 am, with Arnold heading his column’s vanguard. With him came gunners hauling a cannon fixed to a sledge, although the piece was lost to a snowdrift early in the movement. Morgan came next with an additional contingent of riflemen. The Americans were spotted advancing through the dock area and, soon afterward, came across an unpleasant surprise. Their way into the lower town was blocked by a palisade manned by about 30 defenders. Arnold launched a frontal assault but was hit in the foot by a ricochet and knocked out of action. Morgan immediately took over and rushed up a scaling ladder only to tumble back down in the face of a ragged volley. He was unscathed, save for powder burns to his face. Undaunted, he clambered back up, vaulted over the parapet, and managed to avoid the incoming bayonets. The defenders soon lost heart and promptly surrendered.

The Old Wagoner now reconnoitered ahead and found a second barrier, albeit unguarded. He raced back and urged an immediate assault. Instead of heeding the advice, his brother officers debated the situation and concluded it best to wait for the rest of the column to catch up. Concern was also voiced that the prisoners just taken might decide to overpower them. One can only imagine Morgan’s bitter frustration at this point, for his fears proved well-grounded. British and Quebecois units were indeed being rushed to this vital position.

Finally heading a renewed advance, Morgan was called upon to surrender by a Royal Navy officer, who had rashly led a contingent of sailors outside the second palisade. Morgan shot him down and, as the British sailors scattered, shouted: “Quebec is ours!” The Americans dashed into heavy fire, but they were unable to overcome the barrier ahead. Some of the Americans tried outflanking the position via a neighboring house until they were promptly counterattacked and pushed back. Morgan now ordered the men to occupy other nearby properties, hunker down, and fight it out.

Morgan was unaware that Montgomery’s column had already disintegrated after its commander was killed in front of a blockhouse. He was also unaware that the last chance to escape was fast evaporating as the British had successfully cleared the dock area and had been quick to retake the first palisade. They now squeezed the Americans between the two palisades, crushing their opposition by 10 am. Morgan was one of the last to cease fighting, only surrendering after being backed into a corner by leveled British bayonets. Handing his sword to an enemy officer was an anathema, so he passed it to a Quebecois priest instead. The attack had been a disaster: Arnold later reported 30 dead and 42 wounded, while the British would find another 20 American bodies during the spring thaw of 1776. They had also taken 426 prisoners, including Morgan.

Forced to sit on the sidelines for 1776, the Old Wagoner was paroled and fully exchanged by early 1777. He was also promoted to colonel and given command of a regiment, the 11th Virginia. In June, he was also selected to command of the Provisional Rifle Corps, more commonly known as Morgan’s Rifles, of about 500 men including many of his Virginians. Morgan and his men’s main raison d’être was to scout, flank, and push the enemy’s rear guards, which they did to good effect.

By late summer 1777, Morgan and his men were ordered north to make their services available to Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, commander of the Northern Department. Gates was trying to tackle General John Burgoyne’s army of about 7,500 men that had struck deep into New York, bagging Fort Ticonderoga on the way and now threatening Albany. On September 19, the first major battle between the opposing sides occurred in clearings just beyond Freeman’s Farm. The opening shots were fired as British units attempted to deploy opposite Morgan’s rifleman, who were making full use of a treeline for cover. The British wavered and fell back. The Americans chased after them until almost colliding with the enemy’s main advance. The riflemen promptly turned on their heels and raced back for the safety of the treeline with Morgan using the frontiersman’s turkey call, “Gobble, gobble,” to rally them.

For the British soldiers, the morale-raising effect of this incident was quickly dispelled when the unerring and deadly rifle fire resumed. Gunners, officers, and NCOs were especially targeted by Morgan’s men, who were increasingly supported by other units, particularly those under Brig. Gen. Enoch Poor’s command. The tussle for control of the clearings now became a prize fight, with the British decidedly having the worst of it. Burgoyne was eventually saved by three factors. His German units were pushing in from the east; Gates was wary of committing to a full battle; and it was getting late. The Americans broke off, leaving the British in command of the field and the winners of a Pyrrhic victory with 160 dead, 364 wounded, and 42 missing.

Burgoyne returned to his main defensive positions and pondered his next move. On September 22, a message arrived from General Henry Clinton that helped seal his army’s fate. Clinton informed Burgoyne that, if possible, he would push up the Hudson River with 2,000 men in support. In response, Burgoyne ordered his army to dig in and hold out. It took a couple of weeks for Burgoyne to realize that there would be no substantial assistance; even if the relief came, it would be too little too late.

Gambling man that he was, Burgoyne decided to roll the dice and give battle again. On October 7, his troops advanced into Barber’s wheatfield not far from Freeman’s Farm. Morgan was on the American left, helping to contain British efforts to push west. Burgoyne and Brig. Gen. Simon Fraser were instrumental in steadying British nerves and trying to maintain some form of momentum. Riding a gray mount, Fraser ended up directly across from Morgan’s position, and the Old Wagoner responded by ordering a veteran, or possibly a number of veterans, to take down his opposing number. Shortly afterward, Fraser keeled over in his saddle, mortally wounded with an agonizing shot to the stomach.

Fraser’s fall shook British resolve, and it was not long before an inevitable withdrawal became a rapid retreat. Adding to Burgoyne’s woes, Benedict Arnold then went on to capture the vital defensive position of Breymann’s Redoubt, assaulting it from the side just as Morgan’s riflemen were also moving in for an attack. British losses that afternoon were grim: 278 men dead, 331 wounded, and 285 captured. Soon cut off, Burgoyne surrendered his army on October 17.

From 1777 to 1778, Morgan’s Rifles continued to perform well and were involved in harrying the British after the Battle of Monmouth. Later on, Morgan learned that a new light infantry brigade was being formed and, with some justification, believed he was the right man for its command. Thus, he was bitterly disappointed on hearing that Anthony Wayne had been given the position. Morgan responded by taking a furlough and departing for home; however, he might have been grateful for the rest, as campaigning had left Morgan’s frame plagued by chronic sciatica and crippling joint pain.

In 1780, Horatio Gates asked for Morgan’s assistance in the southern colonies. Still smarting from the snub of 1779, the Old Wagoner voiced concern about seniority and requested a promotion first. This was not just pride clouding judgment, for it would be unwise to forget Quebec and Morgan’s inability to assert control at the critical moment. Gates agreed and wrote to Congress asking for a reassessment. Morgan then remained at home until news filtered through of Gates’s crushing defeat at the Battle of Camden, South Carolina. This was the jolt Morgan needed to put aside his grievances and head south. He reached Gates at Hillsborough, North Carolina, in early October and took over the light infantry. Meanwhile, Congress had also done the right thing. Morgan’s promotion to brigadier general became effective on October 13.

The Old Wagoner arrived at the main American camp at Charlotte, North Carolina, in early December. He found an army at low ebb, although its new commander, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, was astute and had decided on a more asymmetric style of warfare. Greene divided his forces to implement this strategy, well aware of the risks in doing so. Morgan entered South Carolina on a mission to disrupt and destroy. His core army numbered 600 men, comprising 320 Maryland and Delaware Continentals, 200 Virginia militiamen, who were actually discharged Continental veterans, and 80 Continental dragoons. Morgan’s infantry was commanded by John Eager Howard, while William Washington, a distant cousin of George Washington, headed his cavalry.

By January 1781, Morgan’s men had caused several major headaches for the British and their loyalist supporters. Commanding an army of roughly 1,150 men, Colonel Banastre Tarleton was ordered to neutralize this menace, and by January 16 Morgan received news that his new opponent was closing in fast. He decided to head for Thicketty Mountain to make use of its defensive terrain but stopped on reaching Cowpens. First, it was fair ground on which to fight, a gently sloping clearing for 800 yards north to south and about 300 yards from east to west. Second, Morgan’s men would be rested while Tarleton’s would be fatigued. Third, it allowed militia units to converge on Morgan’s position, with the arrival of Brig. Gen. Andrew Pickens and his men a particularly welcome addition.

American numbers have created great debate, with historians giving figures that range between 800 and 1,900 men. Morgan himself reported 800 men in a post-battle letter to Greene. Whatever the numbers, the Old Wagoner was particularly worried about his unproven militia units and so formulated a most irregular plan. A screen of riflemen would be deployed about 300 yards ahead of the main line under Lt. Col. John Eager Howard and would ensure an early start to the bloodletting. The riflemen then would fall back to a second position under Pickens’s command that was 150 yards ahead of the main line. At that spot they would find militiamen tasked to deliver just two volleys before they also fell back behind Howard’s men as support.

Morgan spent the night of January 16-17 circulating among the campfires of his men, outlining his objectives, and offering words of encouragement. It also is said he would lift his shirt to show the men the scars on his back and quip that King George still owed him the last lash. Early on the morning of January 17, he roused his army and rode among his troops to reiterate what was required of them. At 6:45 am, the British appeared, with the riflemen starting their harassing fire not long afterward. Tarleton responded by ordering about 50 British Legion horsemen to push forward and scout ahead. Within minutes, 15 of their number were dead from rifle fire.

Ignoring this poor start, Tarleton rushed his lead units into advancing. Just as Morgan had hoped, the British were going to make a frontal assault and, as ordered, the riflemen pulled back to Pickens’s line. The militiamen delivered their two rough volleys and caused a fair degree of damage, although the redcoats were quick to reform and replied with a far more impressive volley. Although some in the militia were left rattled, the withdrawal was nonetheless conducted in comparatively good order. Washington’s troopers also rushed in to cover them when threatened by an enemy cavalry contingent.

Tarleton now inadvertently upset Morgan’s plans by targeting his next advance on the American right. Howard responded by ordering a Virginia company under Captain Andrew Wallace to pull back slightly and prepare itself to meet the threat. However, the command was misinterpreted and instead initiated a calm withdraw down the line. Morgan galloped over and helped fix a new position just beyond a rise and, at 7:45 am, he thundered along shouting: “Face about, boys! Give them one good fire, and the victory is ours!”

The British believed the American withdrawal was the start of a retreat and rapidly advanced over the crest in the expectation of a glorious victory. Instead, they found Howard’s men waiting in good order, muskets raised, and poised to fire. The resulting volley was delivered at 20 to 30 yards, shredding the British front ranks. Howard then cried out for a bayonet charge, with the subsequent melee causing the enemy to collapse. “They fled with the utmost precipitation, leaving [their] field pieces in our possession,” Morgan wrote to Greene. Tarleton watched in disbelief as the remnants of his army streamed past. In desperation, he tried to order his reserve British Legion dragoons into the fray. They refused. So Tarleton also joined the flight, although not before fending off an attack by Washington himself, escaping only by shooting the other’s horse. He left behind a field littered with more than 100 British dead and approximately 800 taken prisoner, including 200 wounded.

For Morgan, the Battle of Cowpens in 1781 was the apogee of his career, a superb result that inspired great confidence as the war neared its dramatic climax. As a reward, Morgan would be given the abandoned estate of a Tory, while a medal was especially struck for him in 1790 to commemorate the event. In many ways, Cowpens marks the end of Morgan’s fighting career as his body was once again wracked with agonizing pain, forcing him to retire. He would briefly join the Marquis de Lafayette that summer but returned home shortly afterward, no doubt then hearing of Cornwallis’s crushing defeat at Yorktown with great satisfaction.

Morgan remained a shrewd businessman after the American Revolution, and there was even one last military hurrah when he commanded a wing of the army sent to crush the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Thankfully, this was resolved without violence. Morgan also dabbled in politics and won a term in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1797 on the Federalist platform. Not too long afterward, on July 6, 1802, the Old Wagoner breathed his last. His passing was mourned by friends, family, veterans, state, and nation.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments