By Anne Saunders

September 1943 was an extraordinary month for the Royal Italian Army. On the 8th, General Dwight Eisenhower and Marshal Pietro Badoglio announced Italy’s surrender to the Allies. A few hours later, top-level Italian leaders deserted Rome for a secure location with Allied forces in southern Italy.

In the chaos that followed, the Italian Army collapsed, making it easier for German troops to occupy Italian towns and cities. In addition, the Germans arrested and deported about 600,000 Italian troops to forced-labor camps and killed the thousands who refused to surrender to the Germans.

Yet German forces could not crush the whole Italian Army, and thus thousands of Italian soldiers and officers were able to join the Resistance, which grew rapidly after September 8. Among those was Colonel Giuseppe Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo, who founded and led the Clandestine Military Front at Rome after serving for many years in the army.

Montezemolo’s goals included helping the Allies defeat the Germans and restoring Italy’s governance, which had been sullied by the Fascist regime of dictator Benito Mussolini. Montezemolo’s life, understood in context, was dedicated to serving his country.

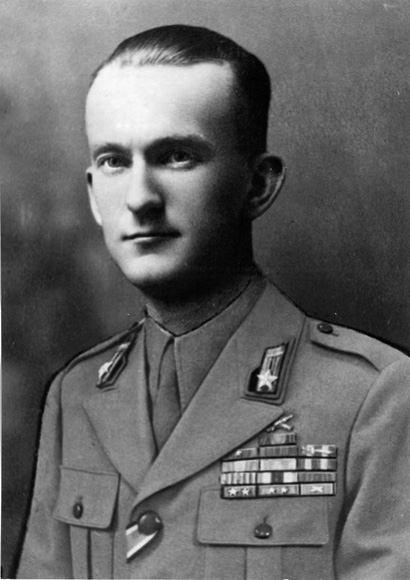

Montezemolo was born in 1901 to an aristocratic family from the Piedmont region with a tradition of military service. His father, uncle, and maternal grandfather were officers in the Royal Italian Army. Montezemolo himself began moving up the military ladder in his late teens.

At age 17, he left school to join an infantry unit and serve in World War I. After the war he went back to his studies, graduating from a university program in civil engineering in 1923. In 1924, he returned to the army as a lieutenant.

In 1935, when war broke out in Ethiopia, Montezemolo was called to Rome to serve in the General Staff Corps. In 1937, he volunteered to serve in the Italian force sent to aid General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. His excellent performance there earned him promotion to lieutenant colonel.

When Italy entered World War II in 1940, Montezemolo was assigned to General Headquarters of the Royal Italian Army in Rome. He first served as an administrator and then as head of the Office of Operations for the campaign in North Africa, where Italian forces initially had some success against Commonwealth troops but soon were suffering significant losses.

To regain the advantage, an Italian delegation including Montezemolo sought help from Hitler in a January 1941 meeting in Germany. The Italians persuaded Hitler to send to Libya one of his best generals, Erwin Rommel, along with German troops, tanks, and vehicles.

Rommel arrived in Libya in mid-February 1941 and set about organizing his men for battle. Through Operation Sonnenblume he succeeded in driving Commonwealth forces out of Libya and capturing all of its towns except for Tobruk.

At Tobruk, Montezemolo spent time on the front and for his service was awarded a bronze medal. Its inscription praises his “serene calm” at a moment when a sudden enemy attack prompted Italian units to retreat. It adds that Montezemolo halted the men, encouraged them, and then reorganized the units for an effective defense, thus stabilizing a “compromised situation.”

Although Montezemolo said that he preferred being at the front, for the most part he served as an administrator during the war. His duties included compiling information and directives for commanders in North Africa and helping them communicate with staff back in Rome. Fluent in German, he handled interaction between Rommel and his Italian counterparts.

During his years in North Africa, Montezemolo’s superiors often noted his outstanding ability to manage people and situations. For example, General Antonio Grandin praised his efforts whether the difficulties involved ongoing operations or “tense relations” between the Italian commanders and Rommel.

In 1942, Montezemolo was awarded another medal for military valor, this time silver. It honored his “risky” flights to Africa, through which he “delivered orders, collected data, and clarified issues,” all of which proved his “deep sense of duty, extraordinary abilities, and disdain for danger.” Those qualities would eventually serve him well in the Resistance.

The war in North Africa continued its seesaw motion in 1942 and early 1943. In October 1942, Commonwealth troops commanded by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery defeated Axis forces at El Alamein in Egypt. However, in February 1943, Axis troops commanded by Rommel overcame American forces at the Kasserine Pass in Tunisia.

Eisenhower replaced the American commander with General George S. Patton, Jr., who swiftly improved the morale, discipline, and battlefield performance of his troops. At the same time, Commonwealth forces continued to gain important victories. By May 1943, the Allies had forced Axis troops out of North Africa.

Defeat in North Africa, as well as the disastrous German campaign in Russia, undermined Mussolini’s authority in the eyes of the Italian people and their rulers. The monarch and high-level officers, a group that included Montezemolo, decided that the moment had come to depose Mussolini. A cluster of events in July 1943 added urgency to that task.

On July 10, the British Eighth Army and the U.S. Seventh Army, collectively a force of over 100,000 men, landed along the southern and eastern coasts of Sicily and quickly overcame Italian troops defending the island. Operation Husky was at the time the largest amphibious operation of the war.

On July 19, Allied aircraft bombed the rail yards around Rome’s main train station, accidentally blasting the surrounding neighborhood and killing hundreds of civilians. That same day, Mussolini, accompanied by Montezemolo and other top officers, met with Hitler at Feltre, a town in northeastern Italy. Mussolini was supposed to make the case for Italy’s withdrawal from the war but was apparently too afraid of Hitler to carry out that task, and for the most part remained silent while the German dictator lectured on what Axis forces must do.

This event and others strengthened the resolve of Italian leaders, including Montezemolo, to depose Mussolini, a move they had been considering for some time. On July 24, 1943, the Fascist Grand Council met with the dictator at Palazzo Venezia, a grand Renaissance palace that housed his offices. After hours of discussion, a majority of the council’s members voted to remove Mussolini from government and command of the armed forces and replace him with Marshal Pietro Badoglio. In effect, they fired their dictator. Mussolini, who seems not to have understood the significance of the vote, returned to Villa Torlonia, his family’s mansion near the center of Rome.

On July 25, Mussolini went to meet with King Victor Emmanuel III at Villa Savoia, the royal residence in Rome. The king informed Mussolini that he must step down and had him escorted to a waiting ambulance; some historians suggest that Montezemolo monitored that event. Guards took Mussolini to the island of Ponza, near Naples, and then to a cabin in the mountains east of Rome.

Back in Rome on July 25, the day Mussolini was deposed, Badoglio instructed Montezemolo to go to Mussolini’s office and gather as many documents as possible; these included dossiers on individuals of interest to the dictator. That evening, the king stunned the Italian people with a radio address announcing that he had accepted the resignation of Mussolini and nominated Badoglio to take his place. That night, Badoglio announced that Italy would continue on in the war as an ally of Germany and proclaimed that “anyone who disturbs the public order will be relentlessly attacked.”

When Hitler learned that Mussolini had been deposed, he was enraged. However, he decided to play along with the king and Badoglio, in part to preserve the country as a source of men and materiel. As a precaution, he ordered more German Army divisions sent to Italy in case it surrendered to the Allies. By the end of August, 16 German divisions were in Italy.

Most Italians rejoiced at the news of Mussolini’s downfall. Many assumed that the war was over, despite Badoglio’s assertion to the contrary. Throughout Italy, people gathered in the streets and piazzas to celebrate. In Rome and Turin, citizens broke open the doors of the main prisons to release political prisoners. Even in POW camps the mood was festive. One prisoner remembered that his guards tossed Mussolini’s picture out the window, tore down Fascist posters, and shouted: “BENITO FINITO.”

Soon after Mussolini was deposed, the leaders of the six major anti-Fascist parties met with Badoglio to make various demands, including an end to the war. Their followers began demonstrating in the streets in favor of freedom and democracy. Badoglio discouraged those assemblies, in part to give the impression that Italy intended to remain an ally of Germany. Although Badoglio and the king in reality wanted to withdraw from that alliance, they tried to conceal that wish from Hitler.

In August 1943, the king’s representatives spent weeks negotiating in secret with their Allied counterparts for terms of a surrender. That process did not go smoothly, but on September 3, in an olive grove near the town of Cassibile in Sicily, General Ugo Castellano signed an unconditional armistice. On September 8, Eisenhower announced the armistice through a radio broadcast. That same evening, Badoglio also spoke on the radio, echoing Eisenhower’s statement and ordering Italian forces to cease hostilities against the Allies.

A few hours later, the king, Badoglio, and other Italian leaders left Rome for a safe haven with Allied forces in Brindisi, a city in southeastern Italy that was to serve as the headquarters for the “Kingdom of the South” until the end of the war.

Why did the king and his leaders bolt? Their behavior was ignoble but not irrational in terms of self-preservation. They must have dreaded what vengeance Hitler might wreak on Italian leaders for quitting the alliance. They felt threatened by anti-Fascists who blamed the king for permitting Mussolini’s rise to power and longed to dispense altogether with the monarchy. Victor Emmanuel and his colleagues preferred to wait for support from the Allies, who had landed at Salerno on September 9 and planned to force the Germans out of Italy.

Whatever their reasons, and to their discredit, Badoglio and other generals left no one in charge of the Italian military when they abandoned Rome. The abrupt exit caused the Italian army to disintegrate quickly. Its commanders did not know what other units were doing, had no practical way to find out, and thus could not develop a coordinated plan.

Many soldiers, left to their own devices, aided civilians in the battle against the Germans. For example, at Porta San Palo in a southern section of Rome, hundreds of Italian soldiers and civilians fought to prevent the Germans from entering the city. Combat then spread to other sections of the Eternal City. However, within two days German forces had suppressed most of the resistance.

On the evening of September 9, Montezemolo and two Italian generals, Giorgio Calvi di Bergolo and Enrico Caviglia, met with General Albert Kesselring in the nearby town of Frascati. Kesselring, head of German forces in Italy, demanded that the Italian military in Rome capitulate and surrender its weapons. In exchange he would declare Rome an “Open City,” demilitarized and not subject to attack. German soldiers were to occupy a limited number of buildings during the day and sleep in the city’s periphery at night.

Kesselring demanded the right to set up a German command in Rome, a requirement contrary to the spirit of an “Open City” arrangement. Since the Italians had no cards to play at this point, they signed the agreement.

In September, German troops settled in Rome’s historic center, took control of local government, and placed tight restrictions on civilian activity. Elsewhere in Italy, they occupied many towns and cities. In addition, Mussolini resurfaced after being rescued and flown to Germany. He was soon broadcasting from his headquarters in northern Italy, where Hitler had made him head of a puppet regime.

Back in Rome, German officials recruited Italians to help them run local civic affairs and assigned them to offices in the center of Rome. Montezemolo sensed that the Germans were suspicious of his loyalty and would soon deport or shoot him. He prepared to go into hiding and join the Resistance.

On September 23, Germans came to Montezemolo’s office to arrest him and his colleagues. Montezemolo had civilian clothes on hand. Donning those, he slipped out of the building and made his escape into the streets of Rome.

To hide his true identity, Montezemolo carried the ID card he had used in Spain in 1937, which said: “Giacomo Cateratto, engineer.”

In the following days, Montezemolo chose other men he knew well to form the initial nucleus of the FCMR (Clandestine Military Front at Rome). The group intended to unite former soldiers and officers now operating independently throughout the city, coordinate with other Resistance groups to force the Germans out of Italy, and put intra-Italian political differences aside until that objective was achieved. The FMCR also called for the construction of a strong intelligence service to aid the Allies, who were battling German forces in southern Italy in the fall of 1943. It encouraged the preservation of public order and respect for the legality of the king’s government.

Although Montezemolo was only a colonel, he had a great deal of prestige and authority in the military and thus was able to bring officers with higher ranks into the FMCR. Among the first to contribute his services was General Raffaele Cadorna, who in October offered to select suitable candidates for the FMCR and also serve as a bridge to political parties. In a letter Cadorna observed, “…Around Montezemolo was united a group of capable officials devoted to him, the nucleus of a large organization that sought to provide the most urgent necessities, and above all information services, to which the Allies attached great importance.”

By October, Montezemolo was known as the leader of the FMCR. The official investiture occurred on October 10th, when this brief query came from the government in Brindisi: “Let us know if Montezemolo is in a situation where he can take on the task of directing and organizing [the FMCR].” To this request, he answered, “Yes.”

As the Allies made their way up the Italian peninsula, battling Germans much of the way, the FMCR helped to keep them informed about the movements of German forces and other pertinent data.

During autumn, Montezemolo and his colleagues also worked to expand the size, scope, and structure of the FMCR. In place of meetings on street corners and in piazzas, they set up three scheduled gatherings per week in apartments loaned by supporters of the Front. They distributed money and weapons to partisan bands. They kept in touch with the Allies and Italian leaders in Brindisi. They began working with partisan groups elsewhere in central Italy, including Latium, Abruzzo, Umbria, and Tuscany. In November, their network extended to selected cities in northern Italy, including Venice, Bologna, Bolzano, and Milan. And among its more mundane tasks, the FMCR produced false identity cards.

That fall, Montezemolo was constantly on the move, meeting with colleagues around Rome. His lifelong talent for facilitating cooperation was useful in his work for the Resistance. For example, although Montezemolo supported the monarchy and was an anti-communist, he and the leader of Italy’s Communist party ordered their groups to cooperate against the common foe. In one of their collective actions, they blew up trains carrying German soldiers, killing or wounding four hundred men.

Montezemolo’s work brought him to the attention of German officials, and by the end of October he knew that the German police were hunting him. He left his cousin’s apartment, moved frequently, and changed the name on his identity card to “Giuseppe Martini, university employee.” But his time was running out: In November, the Germans put a bounty of two million lire on his head.

On January 17, 20, and 22, German officials arrested several members of the FMCR leadership in Rome. About the same time, the Allies landed at Anzio.

On January 25, Montezemolo attended meetings at various spots in the city and had lunch at Via Tacchini 7. As he left the building, he saw five men just outside its main door. They stopped Montezemolo and interrogated him briefly. Realizing they had their catch, the men handed him over to the SS, which took him to a prison on Via Tasso, a little over a mile from Rome’s main train station. There he was interrogated and tortured for weeks on end, but he never broke.

Had he not been in prison on March 23, 1944, Montezemolo might have survived the horrors he suffered there. However, that day a Resistance group killed 33 Austrian soldiers with a bomb in the center of Rome.

As soon as Hitler heard about that bombing, he demanded that ten men be executed for every Austrian who had died. Herbert Kappler, the official in charge, was given a day to collect and kill 330 men. To reach that number on schedule, Kappler added everyone in the Via Tasso prison to his list of “men-to-be-shot.” The list thus included Montezemolo.

The doomed men were taken to the Ardeatine Caves, a few miles south of the Via Tasso prison, and executed on March 24, 1944, a few months before the liberation of Rome.

Today, the public may visit the prison where Montezemolo was held, as well as the place where he was killed and buried. Both can be reached by public bus. At the Ardeatine Caves (renamed the Ardeatine Graves), a mausoleum shelters the tombs of Montezemolo and hundreds of other men who died nearby. Just outside the mausoleum, statues and other works of art commemorate what happened here.

The Via Tasso prison has been renamed the Museum of the Liberation and is a research center. It also preserves intact some of the cells where prisoners were held, including Montezemolo’s small room. Posted there is a letter sent to his widow by Harold Alexander, commander-in-chief of Allied forces in Italy. Alexander expresses gratitude for Montezemolo’s outstanding service to the Allies during the occupation of Rome and adds, “No one could have given more to his country. We regret that he did not live to see the results of his loyalty and self-sacrifice. In him Italy has lost a great patriot and the Allies a true friend.” Those words provide a fitting close to this account of a hero’s life.

Ann Saunders is a research associate with the College of Charleston. She resides in Columbia, South Carolina.