By Allyn Vannoy

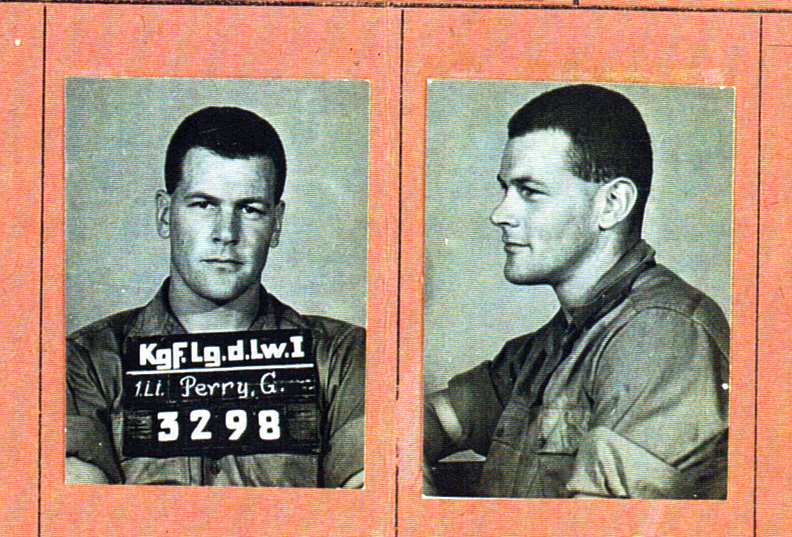

Six B-17G’s of the 416th Bombardment Squadron of the 99th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force, led by Captain B.E. Shaw, departed for Regensburg, Germany, on February 22, 1944. According to the 416th’s war diary, “Three aircraft returned early and three went over the target. No bombs were dropped due to bad weather over the target. The formation was attacked by approximately 10 enemy aircraft. One of our aircraft, #439 piloted by Lt. McGee, was hit and exploded over Augsburg, Germany. #522 piloted by Lt. Perry is missing.”

In the summer of 1941, George F. Perry returned home to St. Helens, Oregon, from his third year at Oregon State College’s School of Engineering. He had already been accepted into the Army Air Corps for pilot training as a flying cadet. He was inducted in Portland on his 22nd birthday, September 18, 1941.

Perry was born in 1919, in St. Helens. His father was a police officer who was killed in the line of duty in November 1924. George and his brother Robert were then raised by their widowed mother.

Perry’s first roommate at Oregon State, was Andy Andrews, later to be his roommate again while at Stalag Luft 1.

Immediately upon induction, Perry and a dozen others boarded a train for California; Perry had never been further than 60 miles from home before. They arrived in Visalia, California, then were bussed to nearby Sequoia Field. The base was still a work-in-progress. Ten weeks of training—half of each day in the classroom and half on the flight line, with 90 minutes in the air.

Perry recalled that with the coming of Sunday, December 7, and the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Americans living near Visalia and Lemoore in the San Joaquin

Valley became more visible, and, although good, patriotic citizens, a paranoia developed, fostered by the federal government and the press.

Upon completion of training at Visalia, Perry was sent just a few miles west to Lemoore, where a new air base was being established and where he received instruction in a Basic Trainer, the BT-15. Next was Advanced Training at Mather Field, Sacramento.

Perry was then assigned to fly the AT-9, a twin-engine aircraft intended to prepare pilots to fly the Douglas B-26 bomber (later the A-26 Invader). While at Mather Field, Perry frequently encountered the movie star Jimmy Stewart, who was also taking flight training. On April 24, 1942, Perry graduated with Pilot Class #42D and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant.

Perry was surprised when his first assignment was as an instructor in basic training of new cadets back at Lemoore. He responded by requesting a reassignment due to his inability to fly the BT-15 well from the back seat, and also because he had just completed multi-engine training. His request was granted, and he was assigned to Navigation School at Mather.

Next, Perry was sent to Hobbs, New Mexico, for four-engine training, then to Pyote, Texas, as a pilot, to pick up a crew. The first assigned to the crew was Bernard C. Kyrouac, co-pilot. Called “BC” or “Bernie,” he stood six-foot-two and weighed about 200 pounds; he had recently graduated from advanced training. Bernie and Perry hit it off from their first meeting; Bernie’s father was the Chief of Police in Harvey, Illinois.

Next was diminutive Joseph M. Joffrion, bombardier, a Louisiana Cajun, just five-foot-four and 110 pounds. He had a great sense of humor and was skilled in his job.

Then there was Armando Ruiz, from El Paso, Texas. He was the flight engineer and top-turret gunner. During flight he stood behind and between the pilot and co-pilot, monitoring the instruments and listening to the engines when not manning the top turret’s twin .50-caliber machine guns.

The individual assigned as radio operator, however, did not exude confidence as Perry assessed him. He seemed to know little about his equipment or how to use it. As other crews were forming up at the same time, Perry overheard another pilot complaining about his radio operator. The other pilot was a tall, blue-eyed individual who Perry thought looked and sounded like he should have been in the Luftwaffe, and his complaint about his radio operator, Hyman Koffler, was that he was a Jew. They agreed to the trade, Perry acquiring a competent operator and a life-long friend.

Next, Dudley R. Segars and Ernest Hettinger were assigned as waist gunners. Donald (Don) Gregory, at five-foot-eight, joined the crew as the ball-turret gunner.

The crew was shipped to Dyersburg, Tennessee, for further training. There they were joined by their navigator, Howard L. Bauman, and their tail-gunner. However, the gunner was reassigned and replaced by Eddie P. Goldstein of the Bronx. This completed their crew of ten.

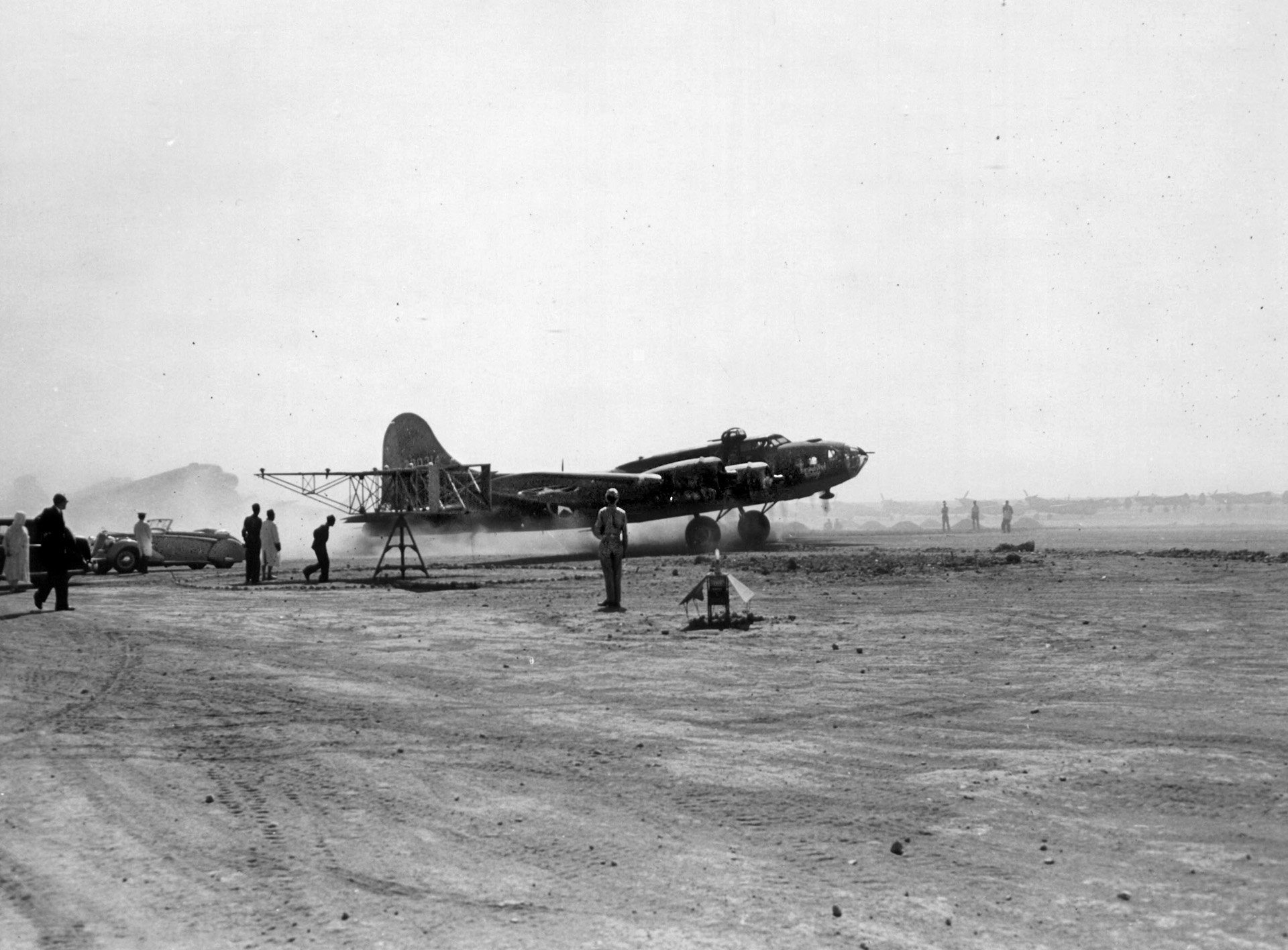

They finally arrived near Tunis during the last week of October 1943. Their air base was at Dudna, about 13 miles southwest of the city, where they were housed in a small tent village beside a desert runway, spending the first week making orientation flights.

They were assigned to the 416th Bombardment Squadron of the 99th Bomb Group, which also included the 346th, 347th, and 348th Squadrons. The 99th was part of the 5th Bomb Wing.

The crew’s first mission came at the end of the first week with the 416th. The 99th was assigned with striking the railroad marshaling yards at Bolzano, Italy, in the Alps. Flight time was five-and-a-half to six hours; 300 bombers were dispatched. Since this was the crew’s first mission, a combat-experienced pilot was assigned to the crew, Perry taking the co-pilot’s seat, as Bernie flew in another plane.

Taking off in the early morning hours of October 30, the flight leader kept the bombers well off the west coast of Italy in order to avoid anti-aircraft fire. As they climbed through 10,000 feet, the crew donned oxygen masks and the air temperature fell. Segars and Hettinger were the most exposed in their open waist windows; however, the others also felt the bite of the frigid air. They reached 24,000 feet, bombing altitude, about 30 minutes before arriving at the IP (Initial Point), from where they would start the bombing run.

Perry recalled, “We entered a layer of air just right for the formation of contrails. Each of the 300 planes put out four white streams, all of which melted together to form one huge, white, banner. It wouldn’t be hard for the anti-aircraft gunners to spot us even though we were five miles above their heads.

“Since each squadron in succession flew behind and below the preceding squadron, no one had to fly in the cloud, so there was a clear view of the target. Also clear was our first look at the explosions of anti-aircraft shells from the 88mm guns on the ground.

“Fortunately, for the most part, they were exploding below our flight path, with only a few at our altitude. As each squadron passed over the target in turn, we would drop our bombs in unison to effect a strike pattern that was concentrated on the target and large enough to cover considerable territory. This was the reason for flying in close formation.”

Coming off the target after shedding their bomb load, they picked up an extra 15-20 miles per hour—helpful in getting out of range of the flak guns.

Nine days later, Perry and his crew flew their second mission, this time to strike a ballbearing plant at Turin, Italy. During the remainder of November they flew three more missions—striking the Bolzano marshaling yards a second time, military targets at Foggia, and an ammunition depot at Fiano Romano.

On November 2, 1943, the four B-17 groups of the 5th Wing, as well as two B-24 groups of the Ninth Air Force, were combined with two fighter groups to form the Fifteenth Air Force.

With the Allied ground advance in Italy, it was decided to relocate the 5th Wing in December of 1943, in order to bring more targets within reach. Each group of the Wing was assigned a base on the Foggia plains, southwest of the spur on the east coast of the Italian boot—the 99th going to Tortorella.

Perry: “Foggia in December was a wet, cold, inhospitable place. I was not feeling well, and my skin was turning yellow. Bernie, Joe, Howard, and I hired some Italian laborers to dig a tent-size hole about four feet deep over which we pitched our tent.

“Lined with slate and tile … heated by a contraption that burned aviation gasoline, we were quite comfortable … except for my extreme gastric distress which was diagnosed as yellow jaundice precipitated by the Atabrine tablets we had been taking to ward off malaria. I was sidelined for a couple of weeks while the crew continued to fly as fill-ins for other crews.”

Royal Air Force units shared the field, flying night missions. Perry said, “Their missions were far more dangerous than ours for several reasons … the first of which was their aircraft. I was amazed and horrified when I climbed into one of their [Vickers] Wellington bombers, which we called ‘Whimpies’ after a Popeye [cartoon] character. It was literally of match-stick construction covered with fabric. It could carry a blockbuster 2000-pound bomb if the bomb bay doors were left off.

“One night we were awakened about one o’clock by a monstrous explosion on the flight line. It was reported that a Whimpy had returned with a bomb hung up and tried to land gently. Many of our planes were put out of commission for the next few days.… Our planes were unable to fly for a while anyway because of the huge hole blown in our runway.

“Another evening just after supper we heard the Whimpies taking off and one flew over our tent area…. We were looking up as one passed overhead, and we noticed a small flame on one wing. The fabric took no time to burn away…. The plane came down about a football field away from our tent. Our 1st Sergeant, Peter B. Hurey, was closest to the crash scene and, seeing the tail turret gunner was still alive, made a dash to extricate him…. He was almost to the plane when a 500-pound bomb exploded. He and all crew members of the plane perished.”

Perry’s next 11 missions with the 99th, from December 1943 to early February 1944, included strikes on marshaling yards at Innsbruck, Austria (December 19); Udine, Italy (December 20); and Prato, Italy (January 17); aircraft factories at Maribor, Yugoslavia (January 7) and Reggio Emilia, Italy (January 8); the submarine base at Pola Harbor, Italy (January 9); enemy troop concentrations and headquarters at Sofia, Bulgaria (January 4); Cassino Monastery (February 15); the Anzio area (February 17); factories at Sofia (February 10); and the airdrome at Compiano, Italy (February 15). Perry considered the Cassino and Anzio missions “milk-runs,” since no enemy aircraft were encountered.

He also felt that the unsung heroes of the operations were the ground crews, who worked day and night to keep the planes flying.

On the morning of February 22, crews were awakened at 4:30 am. After gathering their flight gear and having breakfast, they attended flight briefings. The Fifteenth Air Force was to launch approximately 300 aircraft for the day’s mission, part of Operation Argument—a planned series of coordinated attacks by the Fifteenth and the Britain-based Eighth Air Forces, supported by RAF night raids, targeting the German aircraft industry. It was all part of what became known as “Big Week” by the bomber crews, which began on February 20, 1944. The 416th Squadron was to put up six B-17s, the other three squadrons at least six each, as well.

The 99th’s briefing officer filled the crews in on the opposition they could expect to encounter. Flak was anticipated to be heavy and accurate, with enemy fighters providing maximum opposition.

Perry’s crew for the mission included Lieutenant Bigley, navigator, and Lieutenant Andrezjewski, bombardier—Joe Joffrion had been reassigned to the 416th’s squadron leader Captain Burnham E. Shaw’s aircraft. Bigley had just arrived with a replacement crew and not yet flown a mission, while Andrezjewski had been on just three missions.

The day’s mission was to be carried out at maximum range to strike the Messerschmitt assembly plants and marshaling yards at Regensburg, Germany. The Eighth Air Force, flying from England, was to bomb the same area.

Perry’s aircraft that day was Number 42-31522, named “Spoofer,” a B-17G with a chin-gun turret; all of Perry’s previous missions had been in older “F” models. The chin turret had been added when it was found that German fighter pilots preferred to attack head on, allowing them to target the cockpit of the bomber with minimum time of exposure.

While Bigley and Andrezjewski had both been trained to use the chin turret—the bombardier usually operated it while the navigator worked the .50s on either side of the nose (the cheek guns)—on this mission, the chin turret would freeze up during the heat of battle.

While the lead squadrons started their engines, Perry waited another 10 minutes, since his aircraft was in the last squadron to take off—“Tail-End Charlie”—last in the formation of some 300 planes. Therefore, it would be the last over the target—the most vulnerable and least-desirable position in the formation.

With 300 B-17s in the air trying to form-up, the 416th squadron leader, Captain Shaw, was challenged to organize his formation. Visibility was good at 4,000 feet with a few clouds. Shaw found himself heading for one of the clouds but was able to skirt it. He cleared the cloud with his lead element—his and two other B-17s, which included Perry’s “Spoofer.”

But the second element, behind and below, were unable to avoid the cloud. Taking evasive action to avoid colliding within the cloud, these three planes became separated from the formation and returned to base. The rest of the Fifteenth Air Force was able to complete its formation over the Adriatic Sea, climbing as it headed north. At an airspeed of 135 mph, climbing 150 feet a minute, they would reach the northern end of the Adriatic in about two hours at an altitude of 20,000 feet.

It was extremely cold and uncomfortable in an unpressurized B-17 at high altitude. Some crewmen had electrically heated suits, but not the pilot or co-pilot. The waist gunners were standing before three-by-five-foot openings, and when the temperature in the cockpit fell to 52 degrees below zero, the windchill for Segars and Hettinger, in the open air, could result in frostbite in minutes for any exposed flesh. Don Gregory, in the ball turret, could barely move, while Eddie Goldstein, in the tail, was squatting on a bicycle seat with no room to maneuver.

As the bombers approached land at the northern end of the Adriatic, a few puffs of black smoke appeared. Passing over San Dona, they were greeted by fire from 88mm anti-aircraft guns. Still climbing, crews took a moment to be dazzled by the splendor of the Italian-Austrian Alps in winter. Reaching 22,000 feet, bombing altitude, they leveled off. The target was just an hour away, about 20 miles northeast of Regensburg.

Perry recalled, “As we approached the initial point from the south, we could see several formations making the bomb run and a cloud of black smoke at our altitude over the target. The cloud resulted from the heavy and accurate anti-aircraft fire directed at planes over the target.”

The aircraft intercom came alive with reports from tail gunner Goldstein that bandits (enemy fighters) were approaching from below.

Gregory, in the ball turret, confirmed, “Lots of ‘em.”

Bigley, in the nose: “Fighters at 12 o’clock high.”

Perry said, “I was busy holding formation in our turn at the IP and noted that it seemed Shaw had dropped back a bit more at the rear of the pack; close formation was very important now for a bombing pattern and protection. My right wing tip needed to be even with Shaw’s left wing tip and back just far enough to line up with his tail.”

Reports of enemy fighters were coming in from everywhere, but for some reason they had not spotted the three bombers bringing up the rear of the formation. Suddenly, the wing of a B-17 in the formation ahead of Perry’s seemed to explode and drop off while the plane started a flat spin.

Bombardier Joe Joffrion announced, “Bomb Bay doors open.”

Perry: “We would drop our bombs at the same time as Joe Joffrion triggered those in Shaw’s lead plane. The flak got thicker. The appearance of a flak burst was first a small, intense, red ball of flame followed by thick black smoke that resembled the unfolding of a kernel of black popcorn. The 88mm guns on the ground were in batteries of four and, with the help of overhead observers, were timing their fuses very accurately.

“We counted a string of fiery, black bursts ahead and to our right, another not quite as far ahead and 100 feet left and below. One, two, three, four … too close. There was one out ahead and 50 feet below us, two was closer, three was closer yet, and the fourth we did not see.

“We did feel number four lift the plane and saw several blossoms out on the wings as shrapnel came up through, leaving the kind of mark a .22-caliber bullet would make passing through a tin can. As the same time, I noticed a jagged piece of metal, roughly the size and shape of my little finger, lodged in the nacelle of number two engine just outside my window.”

Though hit, “Spoofer” continued to operate normally.

The three aircraft did not release their bomb loads, as the target area was obscured by either fog or smoke. Noting that the bomb bay doors were closed on the lead plane, Perry’s plane did the same. They flew out of the flak as the formation turned east toward the alternate target, but then the lead planes circled back towards the original IP.

Perry: “Shaw closed up a bit as we turned on the IP for the second time. [There was] a horrendous explosion ahead and to our right as a B-17 took a direct hit in the bomb bay and 10 500-pound bombs exploded. The plane disappeared and several other planes near it went down in flames. Bomb bay doors were opened but, again, the target was [still] obscured, so there was no drop, and the doors were closed [again]. The flak repeated, heavy and accurately. Individual planes dropped out of formation and headed for the ground directly, some in flames, others were crippled.”

In a post-mission report by Maj. Gen. Nathan Twining, American Bomber Command, Italy: “Over Regensburg in February 1944, we suffered the greatest losses ever inflicted on an American Air Force…. From the Alps to Regensburg and back, the bombers battled 300 German fighters. We lost 52 bombers in 100 minutes; 390 American airmen were lost; 190 bailed out onto German soil.”

Perry’s crew next witnessed a series of green and red colored airbursts—a signal to the enemy fighters that they could take on the bombers. “And come they did,” he said, “12 o’clock high, six o’clock low; everywhere.”

The fighters flew ahead and above the bombers. At 12 o’clock high they turned to dive head-on through the bomber formations. There were Bf 109s and F 190s, and even twin-engine Me 210s. Ruiz, standing in the top turret directly behind and above the pilots, exchanged fire with them.

The fighters flew ahead and above the bombers. At 12 o’clock high they turned to dive head-on through the bomber formations. There were Bf 109s and F 190s, and even twin-engine Me 210s. Ruiz, standing in the top turret directly behind and above the pilots, exchanged fire with them.

Kyrouac cried out, “They got McGee!”

Perry remembered, “I saw the left wing of McGee’s plane burning fiercely…. The wing quickly melted away to the nacelle of the number one engine. The flames died out, but the plane could not fly on half a wing; he spiraled down to the right. Our number one engine was hit and lost power, but the propeller did not feather to reduce the drag. The number two engine was hit and lost power. This time the propeller did feather, and we dropped back rapidly. The formation turned east toward the alternate target, but we turned south to get out of the action.

“As we turned, I told the crew to prepare to bail out. We took another raking from a fighter plane that was coming in head-on until we turned. Now he was coming in from the left side; when Segars reached for his parachute, he found it was shredded by shells from his ammo feed belt, which had been hit by a German round.

“Other rounds came through the radio room, and Hy Koffler took several fragments in various parts of his body; one in his forehead, which caused considerable bleeding but did put him out of action.”

With Segars’ chute destroyed, Perry told the crew and Segars that they should stay with the plane, but they were free to jump if they wished. They all decided to stay. They next had to lighten the aircraft, tossing out the guns, ammunition, anything not essential to keep the plane in the air. Andrezjewski salvoed the bombload.

They found themselves approaching the Alps at a much lower altitude than when they had crossed earlier.

After successfully crossing the Alps, fuel became an issue. There was plenty in the left wing with the two dead engines, but the live engines had just about consumed their share of fuel. Perry directed Ruiz, the flight engineer, to transfer fuel from the left to right wing, but the damaged inflicted by enemy fighters was too extensive, preventing the transfer. Given this, it was obvious that they would not be able to return to Foggia.

When they were able to reach the Adriatic, the crew faced a choice. Turning east, they could hope to crash-land in Yugoslavia, where partisans were known to aid Allied crews. Or, turning west and landing in German-occupied Italy, they could expect to spend the rest of the war as POWs. Kyrouac and Perry discussed their choices and decided east and Yugoslavia was their best option.

After sighting land on the horizon ahead of them, they determined that their altitude would not permit them to reach land, so the crew was ordered to prepare to ditch.

Perry: “Our objective was to fly as close to land as possible and set the plane down in the water. There were several unknown factors in this operation. First, we did not realize we were approaching the entrance to the busy harbor of Pola, Italy (present day Pula, Croatia), a facility guarded by German guns because of their submarine base there.

“The crew, except for Bernie [co-pilot Kyrouac] and me, were in the radio room, ready for ditching; we approached the water at a reduced speed, cut the two engines that so faithfully had kept us in the air for the last six hours, and glided in for a water landing. We held the plane up till the last possible moment so we wouldn’t stall too high above the water.

“We were below flying speed, and the belly of the plane made contact with the water. A moment later we were decelerating very rapidly. The plane seemed to bob completely under water and returned to the surface to float like a rubber duck.”

Wounded radioman Hy Koffler remembered, “As water poured into the radio room from the open hatch, we were all huddled on the floor and thought we were going to drown.”

The crew pulled themselves out through the side windows or out of the top hatch of the radio room after releasing the life rafts and crawled onto the wings.

Since Hy and Ernie were bleeding badly, they were the first into the partially inflated life rafts. Each raft was designed to hold five men when fully inflated.

The plane quickly filled with water, and in moments the tail rose in the air and then disappeared below the surface. The crewmembers inflated their “Mae West” life vests.

It was suddenly, eerily quiet, after some six hours of droning engines, flak, and gun fire. But then came machine-gun fire from the shore. It seemed that the Germans thought that the B-17 had been part of a raid intending to strike the nearby submarine pens. Lucky, no one was hit.

After almost an hour in the water, a well-armed German “reception committee” approached in a fishing boat. Perry and his crew were on the verge of hypothermia.

Once ashore, one of the German soldiers pointed to Hy Koffler and Eddie Goldstein and said, “Juden” [“Jews”]. With as stern a look as he could muster, Perry shook his head and responded, “American!” There was no further reference to the subject.

Once at dockside, Perry’s soggy crew was trucked to an imposing, gray stone building that turned out to have been an ancient dungeon.

Perry described the scene: “A crowd of peasant women and children were in front of the large gate that appeared to be the only break in the wall. We learned they were not a welcoming committee but were family members of prisoners incarcerated there. They had come with food to augment the miserable fare provided in the lockup.

“The wing of the prison had a large, open, center area, six-stories high, surrounded by balconies where there was access to the cells. All 10 of us were put into one large cell on the sixth tier. We immediately noticed that the cell didn’t appear to be too secure. The ceiling, roof, and top corner of the cell were missing, allowing the sky to show through. There was no glass in the windows, but there were bars.

“During our stay at Pola we were fed once a day. Each man received about a pint of vegetable soup, the main vegetable being cabbage, and a small loaf of bread which might have weighed in at four to the pound. Through a small hole in the wall between our cell and the next, our Italian neighbors learned who we were and shared some of their better food with us.”

After a week, Perry and his crew were placed aboard a train headed north. Perry said, “We were escorted to the local train station by those soldiers, veterans of the Afrika Korps, whose Hauptmann (captain) in charge was a doctor. I believe they knew the war had been lost and, therefore, treated us in a more kindly manner.

“They did keep an eye on us most of the time, but there were times when their weapons were within our reach and their attention was elsewhere. We discussed the situation among us and decided not to try anything foolhardy. As we traveled, we saw telephone poles along the tracks decorated with the bodies of resistance fighters who had been caught and strung up on the spot.”

They reached Verona, Italy, about March 1, where they underwent interrogations. Perry noted, “My interrogator knew more about the 99th Bomb Group than I did and told me many accurate things about my own 416th Squadron, indicating that he had inside information. I don’t know how he knew we were in the 416th.”

A week later they were placed aboard another train routed through the Brenner Pass, between Italy and Austria. Again, they witnessed bodies hanging from telephone poles along the tracks. Along the way they made many stops and occasionally changed trains.

Their next stop was Frankfurt, Germany, the location of Dulag Luft Interrogation Center and the distribution point for downed airmen. The crew’s six sergeants—Ruiz, Koffler, Segars, Hettinger, Gregory, and Goldstein—were sent to Stalag Luft IV at Keifheide, Pomerania, in northeast Germany. Lieutenants Perry, Kyrouac, Bigley, and Andrzejewski were placed aboard a train bound for the town of Barth and Stalag Luft I, in northern Germany near the Baltic coast.

Perry recalled the train trip: “In the car with us were several injured flyers. I remember most clearly Lieutenant R.D. Vollmer. He was badly burned about the face and had been hospitalized in Germany long enough for some healing to take place. We did what we could to make him comfortable, such as keeping a damp handkerchief over his eyes and mouth while he tried to sleep.

“Later, on a wrapper from a cigarette package, I recorded, ‘The first time I saw Pop Vollmer, he was a pathetic sight. He had a badly wrenched knee and was burned so severely about the face that his mother could not have recognized him. A loose bandage was wound around parts of his face, but his lips and eyes were left uncovered. They showed raw flesh around his eyes and scars around his lips which were extremely hard for us to look at.”

The POWs arrived at Barth on March 13, in snowy weather. The camp was imposing, surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence, 10 to 12 feet high, separated by eight feet, the space between filled with a tangle of barbed wire. At each corner of the prison compound, and also at intervals along the fence, were guard towers equipped with spotlights. The buildings were weathered with gray clapboard siding.

Perry quickly discovered that the camp had an active military organization among the prisoners under the direction of a senior Allied officer, a colonel. Perry: “We were still at war and soon learned that our part was not over. Our job was to occupy as much German manpower and equipment as possible and to do whatever we could to destroy their morale.”

The prisoners in the camp included a few British airmen, but mainly American officers. There were a few fighter pilots, the rest bomber crewmen. Before the war ended, 14 months later, there were more than 8,000 men in the camp.

The prisoners were assembled at least twice a day for roll call, regardless of rain, shine, or snow. On occasion, they were held in ranks for prolonged periods. There were times when the prisoners intentionally caused miscounts to annoy their captors.

Perry remembered the roll call on Easter Sunday, 1944: “After the count was completed, we remained in formation for the Easter service. I don’t recall any grumbling in the ranks, even though we were standing in mud and it was snowing gently from a heavy, gray sky. About halfway through the service we heard the unmistakable thunder of many aircraft.

“From that moment on we just stood and cheered as wave after wave of what we knew to be B-17s and B-24s passed overhead. They were under attack from German fighters because we could hear the chatter of machine guns and a few shell casings fell into the compound. After that, we were required to be in our dorms [barracks] with the shutters closed whenever Allied aircraft were in the vicinity.”

Each barracks was a long building with a door at each end and a hallway down the middle. On either side of the hall were four rooms that each housed 16 to 20 men.

One of the main considerations of the prisoners was food. The Red Cross provided some food parcels that contained canned meat, margarine, a pound of sugar cubes, powdered milk, cheese, a D-ration (chocolate) bar, crackers, or cigarettes. The American cigarettes became barter material, a sort of currency within the camp.

It was intended that each POW to receive one food parcel per week. In reality, at best, there was just one parcel per week for every four men, and later down to one parcel per 16 men.

Each barracks room prepared its own food, with the cooking duties shared. A heavy black bread was supplied on a regular basis. It was soggy and sour, made from rye flour and ground straw. Potatoes, though not abundant, were supplied along with carrots, cabbage, and a large quantity of rutabagas.

The POWs posted men at each end of the building to warn of the approach of German snoops or goons. The goons presented a friendly manner, but their intent was to check on prisoner activity—looking for evidence of tunneling, radios, or other clandestine activity. Some of the guards spoke English while others pretended not to understand it. Daily activities became a contest between the guards and the POWs.

“There were bad times and there were worse times,” Perry said, “or there were good times and better times; it all depended on one’s attitude. All in all, the morale was quite good. After all, this was only temporary; we knew who was winning the war. Our captors supplied us with daily news broadcasts which were primarily propaganda with fictionalized news being fed to the German population.

“We knew how far off this news was because we had the straight scoop from the BBC. The guards knew we had a radio, and there were many times we were ordered out for roll call and then locked out while a thorough search was conducted of the entire compound. Our radio was never found.”

Information from the BBC was used to produce a daily camp newspaper. The paper was carried from room to room, read, and then destroyed.

Shortly after the D-Day invasion, an ambitious individual painted a large map of Europe on the end of one of the barracks. A rope was then strung around nails used to indicate the battle lines according to the German news reports. One day, another rope appeared that showed where the front lines actually were, according to the BBC.

Tunneling was the chief pastime of the POWs. Perry: “I don’t know of any that were successful in providing an escape passage, but they did provide a break from boredom and kept our guards busy. One of the problems we encountered was dirt disposal. After all, a pile of dirt outside a barrack would be a dead giveaway. We had three main methods of disposal. Dumping it into the latrines was the easiest but caused sanitation problems. Another disposal method was the distribution of dirt by exercises as they [the prisoners] walked around the compound dropping a handful at a time from loaded pockets. However, the most creative method was to start a raised garden bed in full view of the guard towers.”

Perry recalled one tunneling effort. The tunnel had progressed beyond the wire, and a group of 12 POWs were readying their escape. Perry said, “In the middle of the night they made their way to the end of the runway tunnel and, as planned, carefully cut out a circle of sod through which they would make their escape.

“As the sod was cautiously moved to the side and the lead man slowly inched his head out into the darkness of the night, he looked directly into the barrels of three rifles pointed at his head. We decided that the Germans were aware of the tunnel and thought the activity was a fine way to keep a good number of men busy.”

During late July 1944, Perry encountered Andy Andrews at the camp. Andy had been his roommate during his sophomore year of college at Oregon State. Perry said, “It was like a letter from home.” They arranged to be roommates again while in the camp.

(Interestingly, in 1992, 48 years later, they were able to locate 10 of their prison roommates and held a reunion with seven of them. “Our ages were nearly tripled, and our looks had changed, but the bond was stronger than it had been those many years ago.”)

In the spring of 1945, the camp commandant told the Senior Officer, Colonel Gabreski, to prepare the prisoners for evacuation, as they would be marched east. Gabreski convinced the commandant that his manpower was inadequate to supervise such a march.

By May 1, 1945, the prisoners could hear the sound of artillery in the distance. One morning they discovered that the camp guards were gone. Opening the gate and cautiously venturing from the camp, they came across Russian soldiers. Perry noted, “The Russians we saw were primarily Oriental-looking Mongolians.” The German civilians they encountered were fearful of these Russians.

“The day before our fences came down,” recalled Perry, “some women walked by about 100 yards from the compound. They were pushing two baby buggies. We later heard five shots ring out. Two babies, two mothers, and a grandmother had decided to die rather than to be subjected to the barbaric treatment being handed out by the Mongolian horde.”

The prisoners were informed that the Russian plan to repatriate them was to ship them by train to the port of Odessa on the Black Sea and then embark them for Western Europe. But the senior American officers, Colonels Zemke and Gabreski, were adamant in their opposition to this plan.

In the days after liberation, the prisoners became restless, but the Russians held fast to their evacuation plan. Perry and nine others decided to head west on foot, to travel light, since they had no idea how far it was to Allied lines. Before setting out, they sewed American flag patches on the shoulder of their uniforms.

As they traveled, they were amazed at the number of vehicles strewn alongside the roadways. Some were military vehicles, but many were farm wagons with dead horses still in the traces. They found the Russian Army drivers they encountered to be very erratic and so, for safety reasons, made an effort to keep off the main roads.

Perry said, “Towards evening, we came to a farmhouse with a large barn. The German family was still there and welcomed us with open arms because they felt safer with us than with the Russians. The Russian troops were bivouacked in the barn; the family had been allowed to stay in the house and we joined them for the night. The Russians were friendly but cool and drew us a map with a suggested safe route to follow.”

Perry and his companions moved through a war-ravaged country. “We often saw bodies, mainly soldiers, beside the road and in the fields as we walked along. As we passed villages, we saw several scaffolds with bodies hanging from them. These we assumed were village leaders rather than soldiers because they wore no uniforms.”

On the third day of their trek, as they passed a German airfield, a young man, seeing their American flag patches, greeted them and then persuaded them to stop. He called to his friends in a nearby barracks. Some 20 men and women swarmed excitedly out to meet them. They turned out to be newly freed slave laborers.

The Americans continued to walk or hitch rides on carts and wagons, always westward. At one point they came upon a large crowd of people gathered by an open field where a single strand of barbed wire had been strung across the field as a line of demarcation. Perry and his compatriots were told that the Russians had strung the wire and had forbidden anyone to cross it on pain of being shot. They were also informed that Allied troops were on the other side of the field.

After spending a night waiting for some direction or action, they found that the waiting crowd had grown in size. There was no hint of Russian guards or movement, but there was fear among the people of what the Russians might do, despite a desire to reach the Allied positions.

Perry: “I was becoming frustrated, hungry, and tired of waiting. The crowd seemed to be looking to the Americans for leadership. About mid-morning I decided to test the water and stepped over the barbed wire with one foot. Getting no response, I put over the other foot. It became very quiet in my vicinity while people watched. Still no response. Looking up and down the wire and seeing no sign of Russian uniforms, I decided to walk toward the Allied lines.

“About 100 yards out into the field, I turned to see the crowd still lined up behind the wire barrier. I waved my arm in a manner to indicate ‘come on,’ and the tide let loose! Hundreds of people had just been waiting for one stupid fool to stick his neck out, and they came like a wave. No shots were fired … no opposition appeared.”

Once across the field, Perry met a Canadian soldier who took him to his unit’s headquarters. The next morning, he was taken to a nearby airport and put aboard a DC-3 headed for Le Havre, France. Processed at Camp Lucky Strike, his next stop was New York and then home.

In time, Perry was able to locate all of his former crewmembers except for Armando Ruiz, meeting them at reunions of the 99th Bomb Group.

George’s brother, Robert, had followed him into the service. Both men were commissioned as officers. Robert served in the Pacific, where he saved the lives of countless airmen as a member of an air-sea rescue unit. After the war, they both returned stateside and became schoolteachers. George passed away in 2006 and Robert in 2007, proud of their wartime service to the end.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments